Abstract

The EspA protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential for the type VII ESX-1 protein secretion apparatus, which delivers the principal virulence factors ESAT-6 and CFP-10. In this study, site-directed mutagenesis of EspA was performed to elucidate its influence on the ESX-1 system. Replacing Trp55 (W55) or Gly57 (G57) residues in the putative W-X-G motif of EspA with arginines impaired ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro and attenuated M. tuberculosis. Replacing the Phe50 (F50) and Lys62 (K62) residues, which flank the W-X-G motif, with arginine and alanine, respectively, destabilized EspA, abolished ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro, and attenuated M. tuberculosis. Likewise, replacing the Phe5 (F5) and Lys41 (K41) residues with arginine and alanine, respectively, also destabilized EspA and blocked ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro. However, these two particular mutations did not attenuate M. tuberculosis in cellular models of infection or during acute infection in mice. We have thus identified amino acid residues in EspA that are important for facilitating ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion and virulence. However, our data also indicate for the first time that blockage of M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro and attenuation are mutually exclusive.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of human tuberculosis (TB), is responsible for significant global morbidity and mortality (1). The type VII ESX-1 secretion apparatus, used by M. tuberculosis to translocate the protein substrates ESAT-6 (or EsxA), CFP-10 (or EsxB), and EspB, underlies the bacterium's remarkable success as a pathogen (2, 3). A facultative intracellular pathogen, M. tuberculosis initially resides within the phagosome of alveolar macrophages, but aided by ESX-1-mediated disruption of the phagosomal membrane, the bacillus presumably escapes into the cytosol of the host cell (4–6). Damage to the phagosomal membrane also induces a proinflammatory response in the host cell, which is followed by necrotic host cell death and the extracellular dissemination of M. tuberculosis (5, 7, 8). Deletion of genes in the M. tuberculosis esx-1 locus, encoding core components of the ESX-1 apparatus, blocks ESAT-6, CFP-10, and EspB secretion and attenuates the bacillus in cellular and animal models of infection (3, 9).

Proteins encoded by the unlinked espACD operon are also critical for the ESX-1 apparatus (10–12). M. tuberculosis espA-null mutants are attenuated, and cosecretion of EspA with ESAT-6 and CFP-10 is crucial for ESX-1 function (11). EspA undergoes Cys138-mediated homodimerization, although the process is not required for EspA or ESAT-6 secretion (13). Nevertheless, replacement of the Cys138 (C138) residue in EspA with alanine attenuates M. tuberculosis, suggesting an ESAT-6-independent role for EspA in virulence (13). Supporting this premise, M. tuberculosis espA-null and EspAC138A-expressing mutants reportedly become hypersensitive to detergents, and therefore, EspA has been postulated to mediate virulence through maintenance of M. tuberculosis cell surface integrity (13). EspC is also cosecreted with ESAT-6 and CFP-10 through the ESX-1 apparatus, and it reportedly interacts with several ESX-1 proteins, such as the cytosolic ATPase, EccA1, and the ESX secretion-associated protein, EspF, to target ESAT-6 and CFP-10 correctly for translocation (14, 15). We have shown that M. tuberculosis EspD is required for the stability of EspA and EspC through an unknown mechanism and for ESX-1-mediated secretion (10). Moreover, EspD is secreted by the tubercle bacillus in a largely ESX-1-independent manner, indicating that its expression but not its secretion is essential for ESAT-6 and CFP-10 translocation (10).

A major objective in type VII protein secretion system research has been the identification of amino acid sequence motifs in protein substrates that govern their recognition and translocation. A conserved Y-XXX-D/E motif was recently found to be required for type VII secretion (16). Located in flexible regions following predicted helix-turn-helix structures at the carboxy terminus, the Y-XXX-D/E motif was identified in CFP-10 and EspB and shown to be required for their secretion (16). It was proposed that substrates of the type VII ESX secretion system either have the Y-XXX-D/E motif or are secreted complexed to substrates carrying the motif (16). In addition, the ESAT-6 WXG100 family of proteins, which includes ESAT-6 and CFP-10, possess a conserved W-X-G motif located in the middle of the protein (3, 9, 17). Structural and biochemical studies have shown that the W-X-G motif in ESAT-6 is situated in a loop linking the two alpha-helices of the protein, and a hairpin conformation of these two helices is important for heterodimerization with CFP-10 (18, 19). Substitution of Trp43 (W43) with arginine in the ESAT-6 W-X-G motif abolishes complex formation with CFP-10 and attenuates M. tuberculosis but has no apparent effect on ESAT-6 or CFP-10 secretion (18). In contrast, replacing Trp43 (W43) with arginine in the CFP-10 W-X-G motif, also located between two alpha-helices, does not affect its interaction with ESAT-6 in vitro (19, 20). Moreover, purified recombinant CFP-10W43R protein stimulates stronger proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated individuals and induces greater production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) than wild-type CFP-10 (20). The effect of mutating Trp43 in CFP-10 on its secretion and on M. tuberculosis virulence is unknown. A W-X-G motif was identified in EspA, but its functional significance is not known (17).

The precise mechanisms by which EspA enables ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion and mediates virulence remain undefined. As EspA is secreted, it is not known if the protein itself has a virulence function separate from its facilitation of ESAT-6 secretion. Accordingly, several M. tuberculosis strains expressing single-amino-acid mutants of EspA were generated and characterized. Here we demonstrate the functional importance of the W-X-G motif and flanking amino acid residues in EspA for ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion and M. tuberculosis virulence. Importantly, we also show that some single-amino-acid replacements in EspA, which cause blockage of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in culture media, do not attenuate M. tuberculosis virulence in cellular and animal models of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and reagents.

Restriction and DNA modifying enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). High-fidelity Pfu polymerase was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Cosmid IE118 (21) containing the M. tuberculosis H37Rv espACD operon was used as the template for PCR cloning. All other chemicals and reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

M. tuberculosis was grown in 7H9 broth (supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 10% albumin-dextrose-catalase [ADC], and 0.05% Tween 80) or on 7H11 agar (supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase [OADC]). The M. tuberculosis Erdman Tn5370 transposon insertion mutant espA::Tn strain and the 5′ Tn::pe35 strain described previously (10) were grown in the presence of hygromycin (50 μg/ml). Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), used for routine cloning, was grown on Luria-Bertani agar or broth. When needed, kanamycin was used at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml for M. tuberculosis and at 50 μg/ml for E. coli.

Plasmid construction and complementation.

Construction of pMDespACD, an episomal plasmid containing the espACD cluster under the control of the native espA promoter, has been described previously (10). Site-directed mutagenesis of espA in pMDespACD was performed using the Quikchange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with the mutagenic oligonucleotides in Table 1 as described previously (10). All constructs generated in this study (Table 1) were verified by sequencing of the espACD operon before electroporation into M. tuberculosis following standard procedures. M. tuberculosis espA::Tn transposon strains harboring pMDespACD and its derivatives were selected on 7H11 agar plates containing kanamycin at 25 μg/ml.

Table 1.

DNA and bacterial strains described in this work

| Plasmid, oligonucleotide, or strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids and cosmids | ||

| pMD31 | Episomal; Kanr oriE oriM | 40 |

| pMDespACD | Episomal; M. tuberculosis espACD Kanr oriE oriM | 10 |

| Oligonucleotidesa | ||

| F5R (sense) | TGAGCAGAGCGCGCATCATCGATCC | This study |

| K41A (sense) | AGTACTTCGAAGCAGCCCTGGAGGA | This study |

| F50R (sense) | TGGCAGCAGCGCGTCCGGGTGATGG | This study |

| W55R (sense) | CGGGTGATGGCCGGTTAGGTTCGGC | This study |

| G57R (sense) | ATGGCTGGTTACGTTCGGCCGCGGA | This study |

| K62A (sense) | CGGCCGCGGACGCATACGCCGGCAA | This study |

| Strains and genotypes | ||

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | Wild type | 41 |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv ΔRD1 | Unmarked deletion of eccCb1 to espK in esx-1 locus | 42 |

| M. tuberculosis Erdman | Wild type | 10 |

| M. tuberculosis Erdman espA::Tn | Transposon insertion in espA | 10 |

| M. tuberculosis Erdman 5′ Tn::pe35 (strain 36-72) | Transposon insertion 102 bp upstream of pe35 in esx-1 locus | 10 |

| M. tuberculosis Erdman ΔpstA1 | Unmarked in-frame deletion of pstA1 | 37 |

| espA::Tn+pMDespACD | espA::Tn fully complemented | 10 |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAF5RCD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAF5R | This study |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAI23RCD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAI23R | This study |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAK41ACD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAK41A | This study |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAF50RCD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAF50R | This study |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAW55RCD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAW55R | This study |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAG57RCD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAG57R | This study |

| espA::Tn+pMDespAK62ACD | espA::Tn complemented, expressing EspAK62A | This study |

Altered codons are underlined.

THP-1 and MRC-5 infections.

To evaluate cytotoxicity induced by different M. tuberculosis strains, two cellular models were utilized, human THP-1 monocytic cells and MRC-5 fibroblast cells. Actively dividing THP-1 cells grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in complete RPMI medium (Gibco RPMI supplemented with glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum) were treated with 10 nM phorbol myristate (PMA), seeded at the required densities in multiwell plates, and allowed to differentiate into adherent phagocytic cells over 3 days. PMA-containing medium was replaced with fresh complete RPMI medium, and the cells were incubated overnight before being infected with M. tuberculosis at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. MRC-5 cells grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in complete MEM (Gibco minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% FCS) were seeded into multiwell plates, allowed to adhere overnight, and infected with M. tuberculosis at an MOI of 8.

The number of M. tuberculosis cells needed to infect THP-1 and MRC-5 cells at the required MOI was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of bacterial cultures (in 7H9 complete medium) and calculating the CFU needed per mammalian cell, assuming 3 × 108 bacterial cells per ml is equal to an OD600 of 1. The required volume of M. tuberculosis cells were then aliquoted into fresh complete RPMI or MEM and added to THP-1 and MRC-5 cells, respectively. Infected THP-1 cells were incubated further without washing for 3 days, while infected MRC-5 cells were incubated without washing for 4 days at 37°C with 5% CO2.

The metabolism of surviving THP-1 and MRC-5 cells after infection and that of uninfected cells were measured with alamarBlue (22). Relative cytotoxicity induced in mammalian cells was determined as follows: metabolic activity of surviving cells infected with different M. tuberculosis strains divided by the metabolic activity of uninfected cells and multiplied by 100.

Analysis of IL-1β and IL-18 secretion by THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates as described above and infected with M. tuberculosis strains at an MOI of 10 for 4 h. After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove nonadherent and noninternalized bacteria, fresh RPMI was added, and the infected THP-1 cells were incubated further for 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. The culture supernatant was filtered, and a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed with appropriate dilutions of the supernatant according to the manufacturer's instructions using the human interleukin 1β (IL-1β) Ready-Set-Go! ELISA kit (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA) and a human IL-18 ELISA kit (MBL Co. Ltd., Japan).

Mouse infections.

Five- to six-week old female C57BL/6 mice (obtained from Charles River Laboratories) were infected via the aerosol route. Log-phase bacterial cultures were centrifuged briefly to exclude cell clumps, and the supernatant was diluted in PBS (supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80) to an OD600 of 0.1 and nebulized with a custom-built aerosol exposure chamber (Mechanical Engineering Shops, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) to deliver approximately 100 CFU of bacteria to the lungs of each mouse. Animal experimentation was performed under authorization 2218 from the Swiss Federal Veterinary Department. Total CFU counts from the lung were evaluated 24 h after aerosol infection and 21 days postinfection. Mice were euthanized, and lung and spleen homogenates were prepared and plated on 7H11 agar plates supplemented with glycerol, OADC, cycloheximide at 100 μg/ml, and ampicillin at 80 μg/ml. Total CFU counts thus measured were log10 transformed and expressed as mean log10 CFU ± standard deviation.

Protein preparation for immunoblots.

Culture filtrates and cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted as described previously (10). M. tuberculosis strains grown to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6 in Sauton's medium containing 0.05% Tween 80 were centrifuged, washed once with PBS, resuspended in Sauton's medium without Tween 80, and grown further at 37°C with agitation for 6 days. Culture filtrate proteins were obtained after cells had been removed by centrifugation and the supernatant had been filtered through 0.2-μm filters and concentrated 100-fold using Vivaspin columns with 5-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff membranes (Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Goettingen, Germany). Cell lysates were prepared by bead-beating cell pellets in ice-cold PBS containing EDTA-free Roche protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Protein concentrations were quantified using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Culture filtrate proteins and cell lysate proteins were resolved in NuPAGE 4 to 12% bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS)–milk (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl and 5% nonfat milk powder). Membranes were incubated overnight with the required primary antibody in TNT-BSA (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, and 1% bovine serum albumin fraction V) at 4°C and with the appropriate secondary antibody in TNT-BSA for 30 min at room temperature and developed using the chemiluminescence reagent Lumi-Light Plus (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). GroEL2 was used as the lysis control for culture filtrates. ESAT-6, CFP-10, EspA, and EspD were detected using anti-ESAT-6 mouse monoclonal antibodies (HYB 76-8), anti-CFP-10 rabbit serum, anti-EspA rabbit serum, and anti-EspD rat serum, respectively. Immunoblots were quantified using open-source ImageJ v1.44i (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) image-processing software. Relative densities of sample/test peaks were obtained by dividing the percent values of samples/test (calculated by ImageJ) by the percent values of the wild-type standard (also calculated by ImageJ). Relative densities of samples/test are indicated in the text as a percentage of the wild-type standard.

SDS sensitivity testing.

SDS sensitivity on 7H11 agar plates was assessed as described previously (23). To measure SDS sensitivity in liquid culture medium, wild-type (WT) M. tuberculosis and the espA::Tn mutant were grown to early log and late log phases in 7H9 medium before exposure to SDS. The sensitivity of M. tuberculosis strains precultured in Sauton's medium instead of 7H9 medium was also tested as described previously (13). WT M. tuberculosis and the espA::Tn mutant were precultured to mid-log phase in either normal 7H9 medium containing 0.2% glycerol, modified 7H9 medium containing 6% glycerol, or Sauton's medium (which also contains 6% glycerol) before exposure to SDS in regular 7H9 medium. Aliquots of these cells were inoculated into 7H9 medium containing 0.1% SDS and incubated for 4 h at 37°C with shaking. After 0- and 4-h exposures to SDS, aliquots were removed, and cells were pelleted, washed with PBS, serially diluted, and plated on 7H11 agar for enumeration of CFU. Percent survival of each strain was calculated by dividing the number of CFU at 4 h postexposure by the number of CFU at 0 h postexposure and multiplying by 100.

Nile red and ethidium bromide uptake assays.

Intracellular accumulation of Nile red and ethidium bromide was used as an indicator of permeability. Bacterial cells were grown in 7H9 medium to an OD600 of 1, pelleted, washed with PBS, and diluted to a final OD600 of 0.4 in PBS. Aliquots (100 μl) were added to 96-well plates with black-walled, clear-bottomed wells. Nile red or ethidium bromide was added to cells, and fluorescence was measured as described previously (24).

Sequence analysis of EspA.

EspA amino acid sequences from M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium leprae, and Mycobacterium marinum were downloaded from TubercuList (25) and aligned for comparison using MultAlin (26). The secondary structure of EspA was predicted using PSIPRED (27). Protein disorder predictions were made using the IUPred, RONN, and OnD-CRF algorithms (28–30).

Statistical analysis.

The significance in differences between experimental groups was determined using Student's t test (two-tailed, unpaired with equal variances) with GraphPad Prism software.

RESULTS

Study rationale.

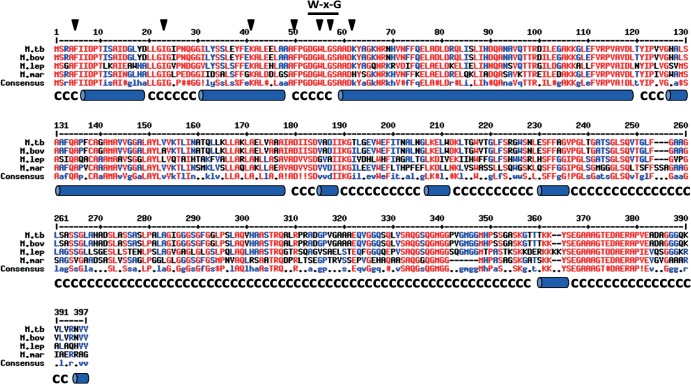

M. tuberculosis EspA, which is composed of 392 amino acids, lacks known functional domains. Nevertheless, it shares 99.5%, 62.7%, and 63.8% sequence identity with EspA homologues from M. bovis, M. leprae, and M. marinum, respectively, that also have functional ESX-1 systems (Fig. 1) (9, 31). M. tuberculosis EspA is predicted to contain four alpha-helices at the amino terminus and random coils at the carboxy terminus (Fig. 1), suggesting that amino acid residues 1 to 260 in EspA are structured and the rest of the protein is disordered (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Notably, Trp55 (W55) and Gly57 (G57) residues in the W-X-G motif of EspA are located in a region between two predicted alpha-helices, a position similar to that of the W-X-G motif in ESAT-6 and CFP-10 (Fig. 1) (17–19).

Fig 1.

Amino acid sequences of EspA from different mycobacterial species. Sequences of EspA from M. tuberculosis (M. tb), M. bovis (M. bov), M. leprae (M. lep), and M. marinum (M. mar) were aligned, and predicted secondary structure is shown below the sequences (alpha-helices are denoted by blue cylinders; C, random coils). Positions of residues mutagenized and characterized in this study are indicated by black arrowheads. The W-X-G motif is indicated.

Site-directed mutagenesis of conserved amino acid residues is a powerful strategy to probe protein function, as illustrated previously with ESAT-6 and EspD (10, 18). A similar approach with EspA was taken and conserved amino acids located along the entire polypeptide, including the W-X-G motif were replaced. Consequently, several pMDespACD plasmids bearing unique missense mutations in espA were generated and transformed into the previously characterized M. tuberculosis Erdman espA::Tn mutant (10). The resulting M. tuberculosis strains expressing variants of EspA grew comparably to the previously characterized complemented strain expressing EspDWT (espA::Tn+pMDespACD) and the control strain harboring the empty vector (espA::Tn+pMD31) (10). These were evaluated for ESX-1-mediated secretion in vitro, ability to induce cytotoxicity in mammalian cells, growth during acute infection in mice and cell surface integrity. Mutant strains that exhibited observable phenotypes are described in more detail below.

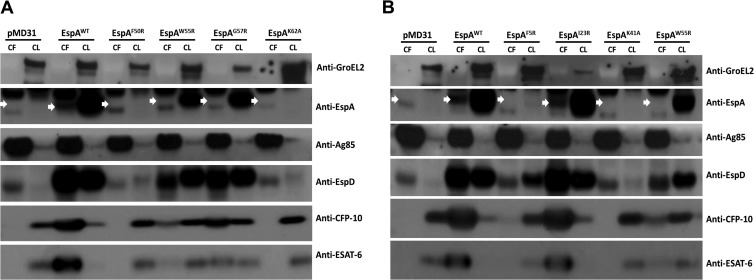

EspAW55R and EspAG57R mutants of EspA are defective in ESX-1 secretion.

The hydrophobic Trp55 (W55) and Gly57 (G57) residues in the W-X-G motif of EspA were replaced with charged arginine residues, as was done with ESAT-6 (18) and CFP-10 (20), to see if ESX-1-mediated secretion and/or virulence of M. tuberculosis might be affected. Indeed, replacing the Trp55 (W55) and Gly57 (G57) residues appeared to cause some EspA instability, with EspAW55R and EspAG57R protein levels being 40 and 63%, respectively, of EspAWT protein levels in the EspAWT-expressing strain ( M. tuberculosis espA::Tn+pMDespACD) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, EspAW55R and EspAG57R proteins could not be detected in the culture filtrates of the corresponding mutants, indicating that they are either not secreted or present at levels below the detection limit (Fig. 2A). ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion by these mutants was also impaired, with the EspAW55R mutation being more disruptive than the EspAG57R mutation. Levels of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 in the culture filtrate of the EspAW55R-expressing mutant were 12 and 37%, respectively, that of the EspAWT-expressing strain (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, levels of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 in the culture filtrate of the EspAG57R-expressing mutant were 35 and 80%, respectively, that of the EspAWT-expressing strain (Fig. 2A). Cellular levels of EspD, which is encoded downstream of and cotranscribed with espA (10), also appeared to be slightly diminished in these two mutants. EspD levels in the cell lysates of the EspAW55R- and EspAG57R-expressing mutants were 85 and 86%, respectively, relative to EspD in the lysate of the EspAWT-expressing strain (Fig. 2A). Decreases in EspD secretion were also observed and this appeared to be more pronounced with the EspAW55R-expressing mutant. EspD levels in the culture filtrates of the EspAW55R- and EspAG57R-expressing mutants were 79 and 90%, respectively, that of the EspAWT-expressing strain (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that the W-X-G motif of EspA is important for optimal secretion of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 and has a modest impact on EspD stability and secretion.

Fig 2.

ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion and expression in M. tuberculosis strains producing EspA variants. Immunoblots of culture filtrates (CF) at 10 μg/well and cell lysates (CL) at 5 μg/well of the espA::Tn+pMD31 control strain, the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT and strains expressing EspAF50R, EspAW55R, EspAG57R, and EspAK62A (A) and the espA::Tn+pMD31 control strain, the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT, and strains expressing EspAF5R, EspAI23R, EspAK41A, and EspAW55R (B) grown in Sauton's medium without Tween 80 for 6 days. Antibodies used are indicated, and the EspA band is indicated by white arrows. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Replacement of Phe5, Lys41, Phe50, and Lys62 severely destabilizes EspA and blocks ESX-1 secretion.

Amino acids flanking the W-X-G motif in EspA are markedly conserved (Fig. 1). Of these, replacement of the hydrophobic Phe50 (F50) residue with arginine and the basic Lys62 (K62) residue with alanine appeared to cause severe instability, as the EspAF50R and EspAK62A proteins produced by the corresponding mutants could not be detected in the cell lysates (Fig. 2A). In addition, replacement of the Phe50 (F50) and Lys62 (K62) residues appeared to abolish ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion, although large amounts of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 were present in the cell lysates (Fig. 2A). Levels of EspD were also greatly reduced in both mutants. EspD levels in the lysates of the EspAF50R- and EspAK62A-expressing mutants were 21 and 11%, that of the EspAWT-expressing strain (Fig. 2A).

Replacement of the EspA Phe5 (F5) residue with arginine and Lys41 (K41) residue with alanine also appeared to cause severe instability. The amounts of EspAF5R and EspAK41A proteins produced by the corresponding mutants were below the detection limit, in contrast to the strains expressing EspAWT or EspAI23R proteins (Fig. 2B). ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion was also abolished in these two mutants, although large amounts of EsxA and EsxB were present in the cell lysates (Fig. 2B). In both mutants, cellular EspD levels were also diminished, although it was higher in the EspAF5R-expressing mutant. EspD levels in the cell lysates of the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants were 64 and 12%, respectively, relative to the EspAWT-expressing strain (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, unlike the strains expressing EspAWT or EspAI23R, EspD could not be detected in the culture filtrates of the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants (Fig. 2B).

These results indicate that Phe5, Lys41, Phe50, and Lys62 (F5, K41, F50 and K62) are critical for the stability of EspA and, indirectly, for EspD, albeit to various degrees. Since EspD deficiency also blocks ESX-1 secretion (10), the combined instability of EspA and EspD appears to completely abolish ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion.

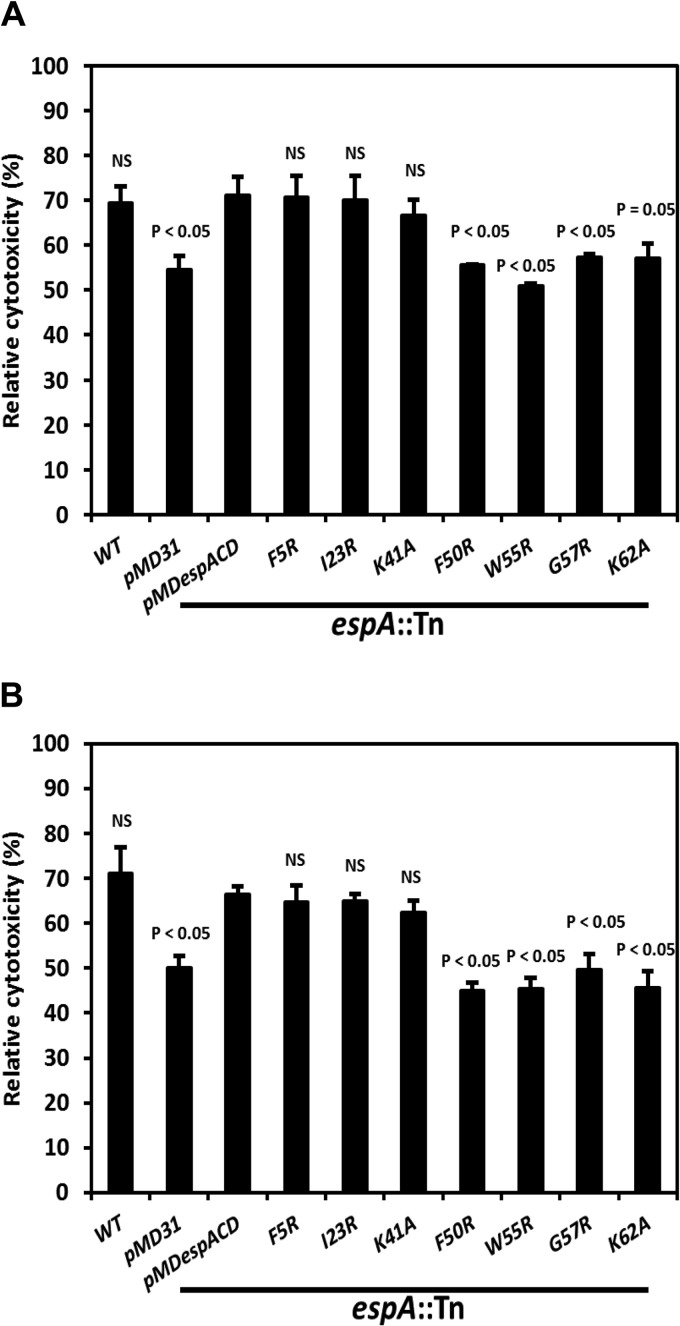

EspAF50R, EspAW55R, EspAG57R, and EspAK62A mutants but not EspAF5R and EspAK41A mutants are attenuated in cellular models of TB infection.

Infection with M. tuberculosis induces cytotoxicity and necrotic cell death of THP-1 monocytes in an ESX-1-dependent manner (5, 8, 32, 33). Accordingly, THP-1 cells were infected with M. tuberculosis strains expressing variants of EspA and the cytotoxicity induced was measured. EspAF50R-, EspAW55R-, EspAG57R-, and EspAK62A-expressing mutants, like the control strain, induced significantly lower cytotoxicity (P ≤ 0.05) than wild-type M. tuberculosis and strains producing EspAWT or EspAI23R (Fig. 3A). Remarkably, despite being unable to secrete ESAT-6 and CFP-10 in vitro, the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants were as cytotoxic to THP-1 cells as wild-type M. tuberculosis and strains producing EspAWT or EspAI23R (Fig. 3A).

Fig 3.

Induction of mammalian cell cytotoxicity by M. tuberculosis strains producing EspA variants. Relative cytotoxicity induced in THP-1 cells infected at an MOI of 5 (A) and MRC-5 cells infected at an MOI of 8 (B) with WT M. tuberculosis, the espA::Tn+pMD31 control strain, the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT, and strains expressing EspA variants. Data are means and standard errors of the means (SEM) from 3 independent experiments. Indicated significances in differences are relative to the fully complemented espA::Tn+pMDespACD expressing EspAWT and were calculated using Student's t test. NS, not significant.

To further verify the results above, MRC-5 cells, a human lung fibroblast cell-line, were also infected with the same M. tuberculosis strains and cytotoxicity evaluated. MRC-5 killing by M. tuberculosis has been used to screen for anti-mycobacterial drugs and to study virulence mutants (34, 35). The EspAF50R-, EspAW55R-, EspAG57R- and EspAK62A-expressing mutants induced significantly lower cytotoxicity (P < 0.05), whereas the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants were as cytotoxic to MRC-5 cells as wild-type M. tuberculosis and strains expressing EspAWT or EspAI23R (Fig. 3B).

These results clearly indicate that mutations in Phe50, Trp55, Gly57, and Lys62 (F50, W55, G57, and K62) of EspA diminish M. tuberculosis-mediated cytotoxicity. However, mutations in Phe5 or Lys41 (F5 or K41) of EspA, despite causing EspA and EspD instability and blocking ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro, do not impact the cytotoxicity of M. tuberculosis in cellular models of infection.

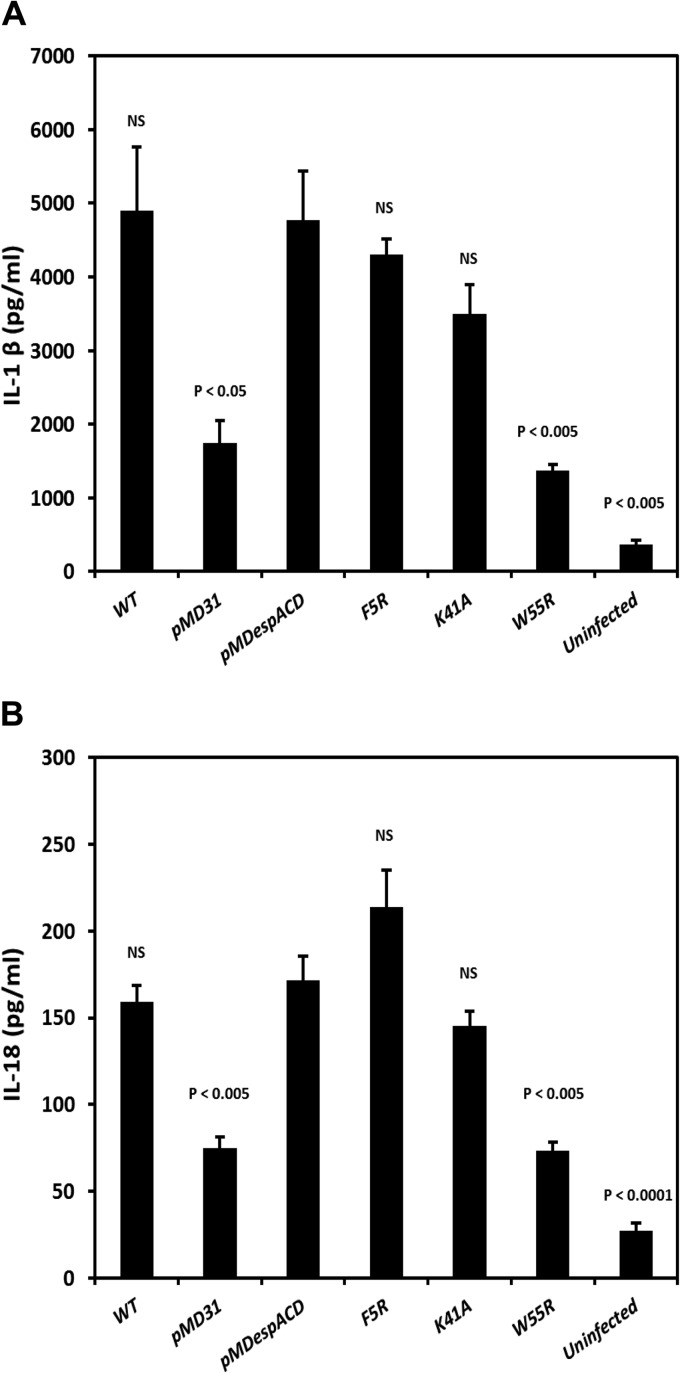

M. tuberculosis EspAF5R and EspAK41A mutants can induce proinflammatory responses in THP-1 cells.

Infection of macrophages with high burdens of M. tuberculosis induces an ESX-1-dependent proinflammatory response, typically characterized by the secretion of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 (7, 8). Accordingly, differentiated THP-1 macrophages were infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis, the EspA mutant control or with strains expressing EspAWT, EspAF5R, EspAK41A, and EspAW55R. Culture supernatants of infected THP-1 cells were assessed for IL-1β and IL-18 production 48 h after infection. Wild-type M. tuberculosis and strains expressing EspAWT, EspAF5R, and EspAK41A all induced 2- to 2.5-fold more IL-1β than the control strain (P < 0.05) and the EspAW55R-expressing mutant strain (P < 0.005) (Fig. 4A). Likewise, wild-type M. tuberculosis and strains expressing EspAWT, EspAF5R, and EspAK41A induced 2-fold more IL-18 than the control strain (P < 0.005) and the EspAW55R-expressing mutant strain (P < 0.005) (Fig. 4B). The cytokine secretion profile obtained here is consistent with the unimpaired ex vivo virulence exhibited by the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutant strains.

Fig 4.

Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in THP-1 cells by M. tuberculosis strains producing EspA variants. Secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β (A) and IL-18 (B) by uninfected THP-1 cells and THP-1 cells infected with WT M. tuberculosis, the espA::Tn+pMD31 control strain, the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT, and strains expressing EspA variants at an MOI of 10. Data are means and SEM from 3 independent experiments in replicate wells. Indicated significance in differences is relative to the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT and calculated using Student's t test. NS, not significant.

EspAF5R and EspAK41A mutants are as virulent as wild-type M. tuberculosis during the acute phase of infection in mice.

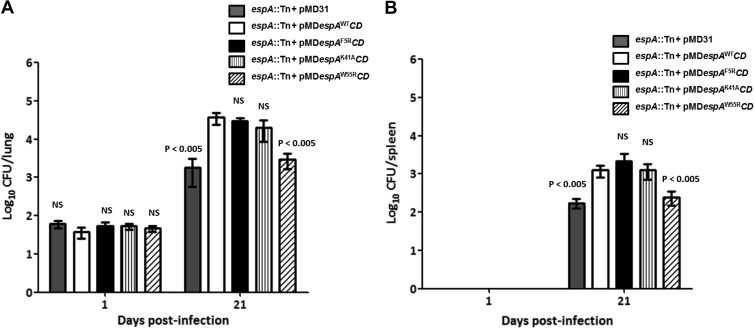

The ESX-1 system is critical to M. tuberculosis during acute infection in mice (33, 36). Given the undiminished capacity of the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants to induce cytotoxicity in mammalian cells despite exhibiting defects in ESX-1-mediated secretion in vitro, we sought to determine if they replicated as well as the EspAWT-expressing strain during acute infection in mice. Accordingly, mice were infected with the espA::Tn control strain harboring the empty vector and strains expressing EspAWT, EspAF5R, EspAK41A, or EspAW55R. At 21 days postinfection, the bacterial burdens in the lungs of mice infected with the strains producing EspAWT, EspAF5R, and EspAK41A were approximately 1 log higher (P < 0.005) than those of the control strain harboring the empty vector and the strain producing EspAW55R (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5.

Bacterial growth during acute infection in mice. CFU per organ recovered from the lungs (A) and spleens (B) of C57BL/6 mice infected via the aerosol route with the espA::Tn+pMD31 control strain, the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT, and strains expressing EspAF5R, EspAK41A, and EspAW55R were determined at 1 and 21 days postinfection. Data are the means and standard deviations of log10 CFU per organ from 4 mice per time point. The indicated significances in differences are relative to the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT (white bar) and were calculated using Student's t test. NS, not significant.

A similar result was also found in the spleens. Bacterial burdens in spleens of mice infected with strains producing EspAWT, EspAF5R, and EspAK41A were approximately 0.9 log higher (P < 0.005) than that of the control strain and the EspAW55R-expressing mutant (Fig. 5B). These results clearly indicate that the M. tuberculosis EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants, despite being incapable of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro, are not attenuated during acute infection in mice.

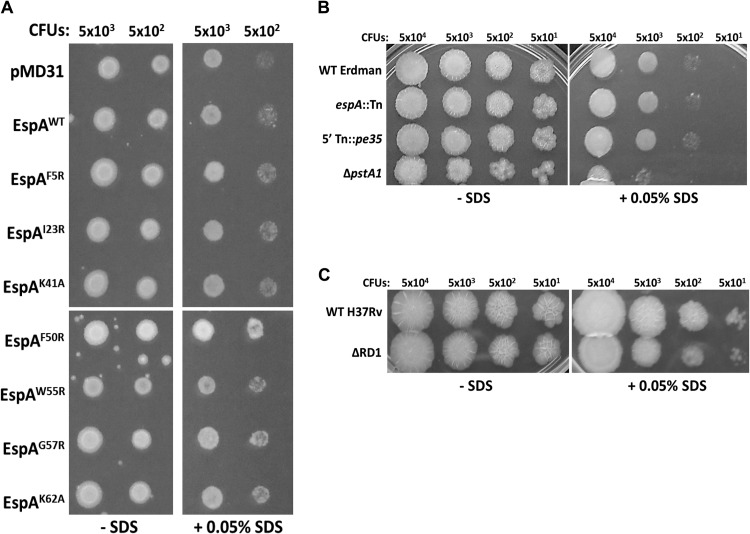

EspA- and ESX-1-deficiency does not affect cell surface integrity of M. tuberculosis.

EspA and the ESX-1 secretion apparatus were postulated to be critical for cell-surface integrity and mutants of M. tuberculosis lacking these were reported to exhibit hypersensitivity to SDS stress (13). We sought to address if enhanced cell surface integrity of the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants compared to the EspAF50R-, EspAW55R-, EspAG57R-, and EspAK62A-expressing mutant strains might underlie their wild-type capacity to kill mammalian cells and replicate during acute infection in mice. Accordingly, SDS sensitivity of the mutant strains and controls was measured using a previously described agar plate-based assay (23). No differences in sensitivity to SDS stress were observed (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, we also did not observe any differences in SDS sensitivity between the EspAWT-expressing strain and the control strain harboring the empty vector (Fig. 6A). To verify these results, wild-type M. tuberculosis Erdman, the isogenic espA::Tn mutant, and the previously characterized 5′ Tn::pe35 mutant (deficient in ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins) (10) were also tested. No differences in SDS sensitivity were observed (Fig. 6B). In contrast, an isogenic pstA1 null mutant known to be hypersensitive to SDS (37) grew poorly in the presence of the detergent (Fig. 6B). To address the possibility that these results might be unique to the M. tuberculosis Erdman genetic background, wild-type M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the isogenic ΔRD1 mutant were also tested. Very modest differences in SDS sensitivity between these two strains were observed (Fig. 6C). Further testing in liquid culture also showed no differences in SDS sensitivity between the wild-type M. tuberculosis Erdman and isogenic espA::Tn mutant (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). Likewise, no differences in the permeability of wild-type M. tuberculosis Erdman and the espA::Tn mutant to hydrophobic (Nile red) and hydrophilic (ethidium bromide) molecules could be detected (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material). These results indicate that EspACD and ESX-1 deficiency does not impact the cell surface integrity of M. tuberculosis.

Fig 6.

Detergent sensitivity of various M. tuberculosis strains. An SDS sensitivity assay was carried out with the espA::Tn+pMD31 control strain (A), the espA::Tn+pMDespACD strain expressing EspAWT, and strains expressing EspA variants, WT M. tuberculosis Erdman, the espA::Tn mutant, the 5′ Tn::pe35 mutant, and the ΔpstA1 mutant (B), and WT M. tuberculosis H37Rv and ΔRD1 strains (C) on 7H11 agar. A 5-μl portion of bacterial culture containing the indicated CFU per strain was spotted on plates. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to explore the structure-function relationship of the EspA protein by means of site-directed mutagenesis of a range of conserved amino acid residues and subsequent phenotypic profiling of transformants expressing the different variants. Besides testing the importance of the W-X-G motif in EspA, we wanted to determine if EspA possessed a distinct effector function in M. tuberculosis virulence. This is especially challenging due to the codependent nature of EspA, ESAT-6, and CFP-10 secretion, but it was reasoned that a genetic approach might facilitate functional deconvolution.

We show that Trp55 (W55) and Gly57 (G57) of EspA are indeed important for EsxA secretion and the virulence of M. tuberculosis. Given the contrasting findings in ESAT-6 (18) and CFP-10 (20), the W-X-G motif appears to serve disparate functions in the ESAT-6 WXG100 family of proteins. Like other ESAT-6 proteins, the structure of the N-terminal domain of EspA is predicted to comprise two alpha-helices in a hairpin conformation separated by the W-X-G motif. This conformation was hypothesized to be important for interaction of EspA with EspC, encoded by the second gene in the espACD operon (17), although such an interaction has not yet been detected despite considerable effort (10, 12, 14). Nevertheless, the EspAW55R and EspAG57R mutants were indeed defective for ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion and were attenuated for virulence in cellular models of infection and in acute infection in mice. While these findings do not preclude a role for the W-X-G motif in recognizing EspC it seems more likely that the motif may be required by EspA to interact with ESX-1 core components or substrates to facilitate secretion. Although no evidence has been obtained for interaction between EspA and ESAT-6 or CFP-10 individually (12, 38), interaction between EspA and an ESAT-6-CFP-10 fusion protein was observed in vivo (38). It was thus proposed that EspA recognizes and interacts only with the ESAT-6-CFP-10 heterodimer to facilitate ESX-1-mediated secretion. Based on the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion profiles, the EspAW55R- and EspAG57R-expressing mutants might be expected to exhibit more residual virulence than the espA::Tn+pMD31 strain; however, this was not the case. In addition to defects in ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion, the EspAW55R- and EspAG57R-expressing mutants also did not secrete EspA and secreted less EspD. Therefore, a reasonable explanation is that optimal EspA, EspC, and EspD secretion is required for virulence, and hence, in the absence of these three secreted proteins, attenuation due to disrupted ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion is exacerbated. This notion is consistent with ESAT-6-independent virulence functions for secreted EspA as seen with the EspAC138A-expressing mutant (13) and a number of EspD point mutants (J. M. Chen and S. T. Cole, unpublished observations).

Substituting residues Phe5, Lys41, Phe50, or Lys62 (F5, K41, F50, or K62) in EspA appears to severely destabilize the protein when M. tuberculosis is grown in vitro. Although the levels of variant EspA detected in the cell lysates of these mutants were below the detection limit, we cannot exclude the possibility that some protein is still present. Furthermore, these mutant strains also exhibit EspD instability, albeit to various degrees, and these defects may synergize to completely abolish ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro. Since EspC stability is also dependent on EspD (10), the stability of EspC in the EspAF5R-, EspAK41A-, EspAF50R-, and EspAK62A-expressing mutants may also be compromised. The basis of mutual EspA, EspC, and EspD stability might not be the formation of a stable complex as there is no evidence of direct physical interaction between these proteins (10, 12, 14). Instead, a threshold concentration of EspA may be necessary for an undefined process that stabilizes both EspC and EspD intracellularly. Further studies to address this are warranted.

The lack of attenuation of the M. tuberculosis EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutant strains suggests that Phe5 and Lys41 (F5 and K41) residues in EspA but not Phe50 and Lys62 (F50 and K62) are dispensable for ESX-1-mediated virulence in cellular and animal models of infection. This is also supported by the observation that the M. tuberculosis EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants elicit wild-type levels of proinflammatory responses in THP-1 macrophages. It is possible that a lower intracellular concentration of EspA is needed by M. tuberculosis to enable ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion during cellular or animal infections than during axenic growth in culture medium. Along these lines, the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants but not EspAF50R- and EspAK62A-expressing mutants may produce sufficient EspA protein, albeit below our detection limits, to support ESX-1-mediated secretion and virulence during cellular or animal infections. Alternatively, host cell factors or direct host cell contact could trigger responses in M. tuberculosis that stabilize EspAF5R and EspAK41A but not EspAF50R and EspAK62A to provide levels sufficient for ESX-1-mediated secretion and virulence. Further characterization of these strikingly dissimilar mutants to address these possibilities is ongoing. Other ESX-1 mutants of M. tuberculosis that display normal ESAT-6 secretion in vitro but are attenuated in cellular and animal models of infection have been described previously (13, 18, 39). The phenotypes displayed here by the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants, however, is the first instance where blockage of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro and attenuation of virulence have been shown to be mutually exclusive.

M. tuberculosis EspA and the ESX-1 system were suggested to mediate cell surface integrity and, as a consequence, virulence. We have obtained no evidence to support this notion, at least in our M. tuberculosis Erdman strains. The EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants were found to be just as sensitive to SDS stress as the attenuated EspAF50R-, EspAW55R-, EspAG57R-, and EspAK62A-expressing mutants. Moreover, EspACD- and ESX-1-deficient M. tuberculosis mutants were as sensitive to SDS stress and as permeable to hydrophobic and hydrophilic compounds as the WT parental strain. Therefore, differences in cell surface integrity likely do not account for the undiminished virulence of the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutant strains.

This study extends our understanding of EspA, but it also underscores its multifaceted role in ESX-1-mediated secretion and M. tuberculosis virulence. Whether the mechanisms underlying the phenotypes exhibited by the EspAF5R- and EspAK41A-expressing mutants are due to host-specific factors or environment-dependent differences in M. tuberculosis modulation of ESX-1-mediated secretion remains to be addressed. Further investigation will provide a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this important pathogen.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Philippe Busso for DNA sequencing.

J.M.C. is a recipient of postdoctoral fellowships from the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. J.R. is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF grant 01KI0771). This study was supported by funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement 201762 and from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A-140778). Antibodies against GroEL2 and Ag85 were received as part of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, contract (no. HHSN266200400091c) entitled “Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Materials,” awarded to Colorado State University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00967-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO 2011. Global tuberculosis control. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bitter W, Houben EN, Bottai D, Brodin P, Brown EJ, Cox JS, Derbyshire K, Fortune SM, Gao LY, Liu J, Gey van Pittius NC, Pym AS, Rubin EJ, Sherman DR, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2009. Systematic genetic nomenclature for type VII secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000507. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simeone R, Bottai D, Brosch R. 2009. ESX/type VII secretion systems and their role in host-pathogen interaction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houben D, Demangel C, van Ingen J, Perez J, Baldeon L, Abdallah AM, Caleechurn L, Bottai D, van Zon M, de Punder K, van der Laan T, Kant A, Bossers-de Vries R, Willemsen P, Bitter W, van Soolingen D, Brosch R, van der Wel N, Peters PJ. 2012. ESX-1-mediated translocation to the cytosol controls virulence of mycobacteria. Cell Microbiol. 14:1287–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simeone R, Bobard A, Lippmann J, Bitter W, Majlessi L, Brosch R, Enninga J. 2012. Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002507. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Wel N, Hava D, Houben D, Fluitsma D, van Zon M, Pierson J, Brenner M, Peters PJ. 2007. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell 129:1287–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welin A, Eklund D, Stendahl O, Lerm M. 2011. Human macrophages infected with a high burden of ESAT-6-expressing M. tuberculosis undergo caspase-1- and cathepsin B-independent necrosis. PLoS One 6:e20302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong KW, Jacobs WR., Jr 2011. Critical role for NLRP3 in necrotic death triggered by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Microbiol. 13:1371–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoop EJ, Bitter W, van der Sar AM. 2012. Tubercle bacilli rely on a type VII army for pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol. 20:477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JM, Boy-Rottger S, Dhar N, Sweeney N, Buxton RS, Pojer F, Rosenkrands I, Cole ST. 2012. EspD is critical for the virulence-mediating ESX-1 secretion system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 194:884–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortune SM, Jaeger A, Sarracino DA, Chase MR, Sassetti CM, Sherman DR, Bloom BR, Rubin EJ. 2005. Mutually dependent secretion of proteins required for mycobacterial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:10676–10681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacGurn JA, Raghavan S, Stanley SA, Cox JS. 2005. A non-RD1 gene cluster is required for Snm secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1653–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garces A, Atmakuri K, Chase MR, Woodworth JS, Krastins B, Rothchild AC, Ramsdell TL, Lopez MF, Behar SM, Sarracino DA, Fortune SM. 2010. EspA acts as a critical mediator of ESX1-dependent virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by affecting bacterial cell wall integrity. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000957. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiGiuseppe Champion PA, Champion MM, Manzanillo P, Cox JS. 2009. ESX-1 secreted virulence factors are recognized by multiple cytosolic AAA ATPases in pathogenic mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 73:950–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millington KA, Fortune SM, Low J, Garces A, Hingley-Wilson SM, Wickremasinghe M, Kon OM, Lalvani A. 2011. Rv3615c is a highly immunodominant RD1 (Region of Difference 1)-dependent secreted antigen specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:5730–5735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daleke MH, Ummels R, Bawono P, Heringa J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Luirink J, Bitter W. 2012. General secretion signal for the mycobacterial type VII secretion pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:11342–11347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das C, Ghosh TS, Mande SS. 2011. Computational analysis of the ESX-1 region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: insights into the mechanism of type VII secretion system. PLoS One 6:e27980. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brodin P, de Jonge MI, Majlessi L, Leclerc C, Nilges M, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2005. Functional analysis of early secreted antigenic target-6, the dominant T-cell antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, reveals key residues involved in secretion, complex formation, virulence, and immunogenicity. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33953–33959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renshaw PS, Lightbody KL, Veverka V, Muskett FW, Kelly G, Frenkiel TA, Gordon SV, Hewinson RG, Burke B, Norman J, Williamson RA, Carr MD. 2005. Structure and function of the complex formed by the tuberculosis virulence factors CFP-10 and ESAT-6. EMBO J. 24:2491–2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meher AK, Lella RK, Sharma C, Arora A. 2007. Analysis of complex formation and immune response of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 mutants. Vaccine 25:6098–6106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bange FC, Collins FM, Jacobs WR., Jr 1999. Survival of mice infected with Mycobacterium smegmatis containing large DNA fragments from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 79:171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanova L, Uhlig S. 2008. A bioassay for the simultaneous measurement of metabolic activity, membrane integrity, and lysosomal activity in cell cultures. Anal. Biochem. 379:16–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandal OH, Roberts JA, Odaira T, Schnappinger D, Nathan CF, Ehrt S. 2009. Acid-susceptible mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis share hypersusceptibility to cell wall and oxidative stress and to the host environment. J. Bacteriol. 191:625–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Tran V, Li M, Huang X, Niu C, Wang D, Zhu J, Wang J, Gao Q, Liu J. 2012. Both phthiocerol dimycocerosates and phenolic glycolipids are required for virulence of Mycobacterium marinum. Infect. Immun. 80:1381–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew JM, Kapopoulou A, Jones LM, Cole ST. 2011. TubercuList—10 years after. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 91:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corpet F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:10881–10890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuffin LJ, Bryson K, Jones DT. 2000. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 16:404–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. 2005. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21:3433–3434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Sauer UH. 2008. OnD-CRF: predicting order and disorder in proteins using [corrected] conditional random fields. Bioinformatics 24:1401–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang ZR, Thomson R, McNeil P, Esnouf RM. 2005. RONN: the bio-basis function neural network technique applied to the detection of natively disordered regions in proteins. Bioinformatics 21:3369–3376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer JS, Kim HJ, Marques AM, Gonzalez-Juarerro M, Lima MC, Vissa VD, Truman RW, Gennaro ML, Cho SN, Cole ST, Brennan PJ. 2004. Comparative analysis of B- and T-cell epitopes of Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate protein 10. Infect. Immun. 72:3161–3170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Mathur SK, Zakel KL, Grotzke JE, Lewinsohn DM, Smith S, Sherman DR. 2004. Individual RD1-region genes are required for export of ESAT-6/CFP-10 and for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 51:359–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis KN, Liao R, Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Smith S, Behr MA, Sherman DR. 2003. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis mimics bacille Calmette-Guerin attenuation. J. Infect. Dis. 187:117–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrer NL, Gomez AB, Soto CY, Neyrolles O, Gicquel B, Garcia-Del Portillo F, Martin C. 2009. Intracellular replication of attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis phoP mutant in the absence of host cell cytotoxicity. Microbes Infect. 11:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takii T, Yamamoto Y, Chiba T, Abe C, Belisle JT, Brennan PJ, Onozaki K. 2002. Simple fibroblast-based assay for screening of new antimicrobial drugs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2533–2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanley SA, Raghavan S, Hwang WW, Cox JS. 2003. Acute infection and macrophage subversion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis require a specialized secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:13001–13006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tischler AD, Leistikow RL, Kirksey MA, Voskuil MI, McKinney JD. 2013. Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires phosphate-responsive gene regulation to resist host immunity. Infect. Immun. 81:317–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callahan B, Nguyen K, Collins A, Valdes K, Caplow M, Crossman DK, Steyn AJ, Eisele L, Derbyshire KM. 2010. Conservation of structure and protein-protein interactions mediated by the secreted mycobacterial proteins EsxA, EsxB, and EspA. J. Bacteriol. 192:326–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bottai D, Majlessi L, Simeone R, Frigui W, Laurent C, Lenormand P, Chen J, Rosenkrands I, Huerre M, Leclerc C, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2011. ESAT-6 secretion-independent impact of ESX-1 genes espF and espG1 on virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 203:1155–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donnelly-Wu MK, Jacobs WR, Jr, Hatfull GF. 1993. Superinfection immunity of mycobacteriophage L5: applications for genetic transformation of mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 7:407–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, III, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, Chen M, Dai AZ, Morin PM, Marks CB, Padiyar J, Goulding C, Gingery M, Eisenberg D, Russell RG, Derrick SC, Collins FM, Morris SL, King CH, Jacobs WR., Jr 2003. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12420–12425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.