Abstract

Objective

The primary goal of this paper is to examine and clarify characteristics of binge eating in individuals with binge eating disorder (BED), particularly the duration of binge eating episodes, as well as potential differences between individuals with shorter compared to longer binge eating episodes.

Method

Two studies exploring binge eating characteristics in BED were conducted. Study 1 examined differences in clinical variables among individuals (N = 139) with BED who reported a short (< 2 hours) versus long (≥ 2 hours) average binge duration. Study 2 utilized an ecological momentary assessment (EMA) design to examine the duration and temporal pattern of binge eating episodes in the natural environment in a separate sample of nine women with BED.

Results

Participants in Study 1 who were classified as having long duration binge eating episodes displayed greater symptoms of depression and lower self-esteem, but did not differ on other measures of eating disorder symptoms, compared to those with short duration binge eating episodes. In Study 2, the average binge episode duration was approximately 42 minutes, and binge eating episodes were most common during the early afternoon and evening hours, as well as more common on weekdays versus weekends.

Discussion

Past research on binge episode characteristics, particularly duration, has been limited to studies of binge eating episodes in BN. This study contributes to the existing literature on characteristics of binge eating in BED.

Binge Eating Disorder (BED), originally introduced as a provisional eating disorder diagnosis in the appendix of the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) [1], is now included as a full diagnostic entity in the DSM-5 [2]. According to the DSM-5 criteria, a binge eating episode is characterized by: (a) consuming a significantly large amount of food in a discrete period of time (e.g., within two hours) compared to what most others would eat under similar circumstances; and (b) the presence of a subjective sense of loss of control over eating. Although this definition of binge eating specifies a broad duration criterion by example (i.e., occurring within a discrete time period of two hours or less), there is little information regarding binge eating episode duration and whether duration of binges is associated with clinically relevant variables (e.g., severity of eating disorder psychopathology or co-occurring affective disturbance), particularly in BED.

Early research on binge eating behavior focused on patients with bulimia nervosa (BN). For example, Mitchell, Pyle, and Eckert [3] examined characteristics of binge eating based on self-reports in patients with BN, finding a mean binge eating episode duration of slightly more than one hour, with a range from 15 minutes to 8 hours. Similarly, Mitchell and Laine [4] examined binge eating characteristics in a small sample of normal-weight patients with BN over a 24-hour period. The average binge eating episode duration was approximately one hour, and results suggested that participants had noticeably abnormal eating patterns (i.e., type of food consumed and order in which the type of food was consumed) during both normal and binge eating episodes. More recently, a study by Kissileff, Zimmerli, Torres, Devlin, and Walsh [5] examined caloric intake among normal controls and individuals with BN, who were asked to binge eat a yogurt shake served at either a slow or fast rate in a structured laboratory setting. Normal controls consumed more calories during the fast condition than in the slow condition. As expected, individuals with BN consumed more on average than normal controls, but calories consumed did not differ across the fast and slow conditions among BN participants.

While a small amount of empirical study has examined differences between BED and BN [6], little is actually known about differences in binge eating between these clinical groups. Better understanding of the clinical features of binge eating in both BN and BED, and the differences between these features, may prove informative regarding the precipitants and maintaining factors associated with binge eating in both clinical populations.

Recent studies have examined features and correlates of binge eating and other eating behavior in BED (e.g., meal size and BMI [7]; hunger and fullness [8]). Research on binge eating in laboratory settings has consistently revealed that individuals with BED consume significantly more calories than individuals without BED, regardless of whether or not participants are explicitly instructed to binge eat [9]. However, other features of binge eating in BED, such as duration of binge eating episodes, have not been examined in detail. Empirical findings regarding the duration of binge eating episodes in BED are particularly lacking. Considering this gap in the existing literature, there is a need for additional data on this feature of binge eating, particularly given that this criterion is included within the diagnostic definition of what constitutes an episode of binge eating.

The primary goal of this investigation was to further examine and clarify binge eating in individuals with BED, with a particular emphasis on the duration of binge eating episodes. Two studies were conducted with separate BED samples. The first utilized self-report data collected via semi-structured interviews and questionnaires and allowed a comparison of individuals with self-reported short versus long average binge eating episode durations. The second utilized ecological momentary assessment (EMA), an assessment methodology used in numerous studies of binge eating [10-14], to examine the mean duration and temporal patterns (i.e., across the hours of the day, and across the days of the week) of binge eating in the natural environment.

Study 1

Method

Complete details of the methods used in Study 1 have been previously reported [15]. In brief, participants were recruited from community settings (e.g., advertisements for a research on the treatment of binge eating) and through referrals from local eating disorder treatment clinics and other health professionals. After consenting to be in the study, 259 adult participants diagnosed with BED were randomly assigned to one of three different group treatments for BED (therapist-led, therapist-assisted, or structured self-help) across two sites (Fargo, ND and Minneapolis, MN). Treatment duration was 20 weeks. Participants were diagnosed with BED using the Eating Disorder Examination [16]. Participants also completed other measures, including the Inventory for Depressive Symptoms (IDS) [17], the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [18], The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each site.

Data for the current study includes a subset of participants (n=139) from the larger sample who completed a standardized series of questions incorporated into the baseline EDE interview were included in the current analyses. The subset of participants included men (n=17) and women (n=122) with a mean BMI of 38.7 kg/m2 (SD=7.8) and a mean age of 47.5 years (SD=10.8). The majority (96.4%) of these participants were Caucasian. Based on the EDE interview, the mean frequency of objective binge eating episodes during the previous 28 days was 23.0 episodes (SD=15.2). Following the assessment of objective binge eating, participants were asked: “Over the last 28 days, on average, how long have your episodes of overeating lasted from beginning to end?” Participants were subsequently asked to report the duration of the longest objective binge eating episode, and the shortest objective binge eating episode.

Results

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare the short duration and long duration binge eating groups on variables including eating disorder symptoms, co-occurring psychopathology, and other psychological symptoms. Based on participants' self-reported average binge eating episode duration, participants were classified into one of two groups: short duration binge eating (average duration of 2 hours or less; n = 113) or long duration binge eating (average duration of more than 2 hours; n = 26). The groups were then compared (see Table 1) on a number of eating disorder variables (shortest, longest, and average self-reported binge duration, as well as EDE global and subscales scores) and co-occurring psychopathology and psychological symptoms. As anticipated, significant differences were found between the groups for the self-reported shortest, longest, and mean duration of binge eating episodes, with the long duration group reporting a greater duration on all three variables compared to the short duration group. No significant differences were found for the EDE global score or for any of the subscale scores. In contrast, significant differences were found for both depressive symptoms and self-esteem scores, with the long duration group reporting greater symptoms of depression and lower self-esteem compared to the short duration group. No significant differences were found across the two groups for BMI, age, or sex.

Table 1. Comparison of Binge Eating Disorder participants reporting Short Duration (i.e., less than two hours) versus Long Duration (i.e., greater than two hours) average binge eating episode duration (N = 139).

| Short Duration (n = 113) | Long Duration (n = 26) | t | p | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Average Duration (mins) | 64.58 | 36.13 | 216.92 | 55.19 | -13.43 | <.001 | 3.27 |

| Shortest Duration (mins) | 31.02 | 22.46 | 108.65 | 72.37 | -5.41 | <.001 | 1.45 |

| Longest Duration (mins) | 158.45 | 125.45 | 393.46 | 153.75 | -8.24 | <.001 | 1.67 |

| RSES | 2.52 | 1.87 | 3.50 | 2.09 | -2.18 | =.031 | 0.49 |

| IDS | 23.08 | 10.39 | 31.36 | 11.52 | -3.15 | <.001 | 0.75 |

| EDE Global | 2.60 | 0.82 | 2.91 | 0.84 | -1.75 | =.083 | 0.37 |

| EDE Restraint | 1.58 | 1.23 | 1.97 | 1.39 | -1.41 | =.161 | 0.30 |

| EDE Eating Concern | 1.82 | 1.20 | 2.06 | 1.15 | -0.92 | =.357 | 0.20 |

| EDE Shape Concern | 3.54 | 0.96 | 3.82 | 0.91 | -1.38 | =.170 | 0.30 |

| EDE Weight Concern | 3.45 | 1.06 | 3.79 | 1.03 | -1.47 | =.144 | 0.33 |

Note. RSES = Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; IDS = Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology; EDE = Eating Disorder Examination Interview.

Although the differences found in Study 1 are interesting, they are limited by the retrospective nature of the binge eating duration assessment. In Study 2 we used a much more thorough assessment of binge duration that is not nearly so reliant on retrospective recall.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study were a subset of individuals drawn from a larger study of 50 obese adults (BMI>30) aged 18-65 who were recruited through community advertisements and flyers. The current study reports on data from a subset of 9 women, who were diagnosed with current full (n=5) or subthreshold (n=4) BED (e.g., binge eating episodes occurring regularly but less than twice per week) using the eating disorders module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient Edition [19]. This subset of participants had a mean BMI of 49.9 kg/m2 (SD=11.8) and a mean age of 37.9 years (SD=11.8). The majority (77.8%) of these participants were Caucasian. The average duration of illness for BED in the sample was 14.4 years (SD=11.3).

Procedure

Individuals who were interested in the protocol were first phone screened. Those who appeared to qualify attended an informational session at the research facility (Minneapolis, MN) during which participants provided informed consent and completed assessments to confirm eligibility. Those who qualified and chose to participate were trained in the use of a hand-held computer during the two-week EMA protocol in accordance with the study guidelines. EMA uses handheld, electronic devices to collect momentary data in participants' natural environment. The use of EMA helps to avoid the artificiality of the laboratory setting and minimizes retrospective recall biases of the reported behavior of interest [20]. Participants carried their hand-held computers during their normal daily routine for a two-week period. They returned to the research facility approximately twice per week to allow for data uploads in an effort to minimize data loss in the event of technical problems. The pre- and post-eating episode recordings were used in this study to derive a measure of duration of binge eating episodes. During the EMA data collection period, participants were asked to complete a variety of ratings before and after each eating episode (i.e., meals, snacks, binge eating). Ratings for overeating (“To what extent do you feel that you overate?”) and loss of control over eating (“While you were eating, to what extent did you feel a sense of loss of control?”) were made on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=not at all, 3=moderately, 5=extremely). Episodes characterized by both overeating and loss of control, defined by a rating of ≥3 on both constructs, were classified as binge eating episodes. Participants were also asked to respond to six semi-random signals throughout the day, which assessed mood, attitudes, and activities, as well as end of the day ratings (data from these random signals and end of day ratings are not reported in the current study). Binge eating episode duration was determined by calculating the difference between the starting and ending time reported for each episode. The study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Results

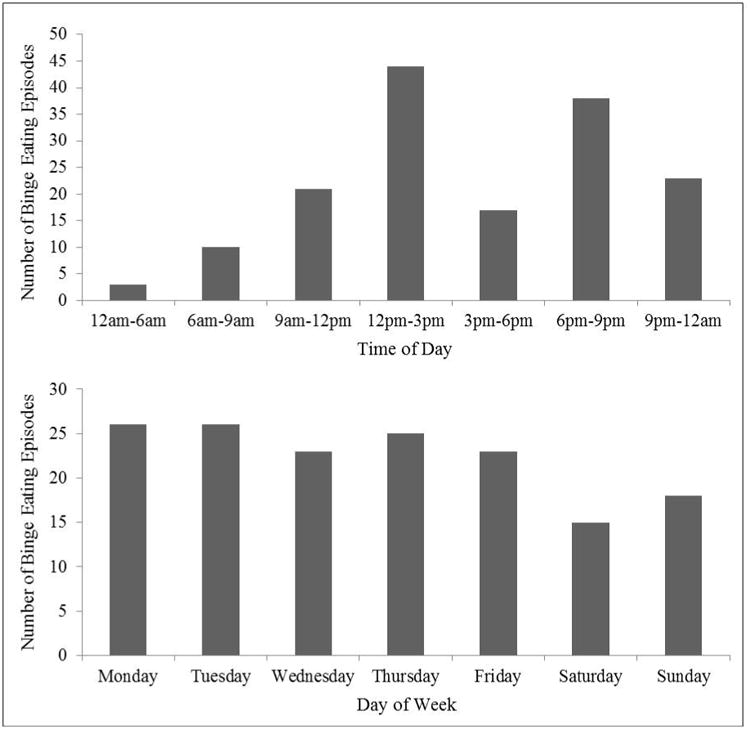

Descriptive data including means and standard deviations were calculated to characterize the duration and patterns of binge eating episodes in the current sample. Participants reported a total of 156 binge eating episodes during the course of the EMA data collection period. Of these episodes, 118 (75.6%) included both pre- and post-episode reports, allowing for the calculation of binge eating duration for these episodes. Binge eating descriptive data are reported in Table 2. Across the 118 episodes with duration data, the average duration of binge episodes was approximately 42 minutes, although the duration ranged from two minutes to 2.6 hours. Further, the mean number of binge eating episodes per day and per week were calculated. On average, participants reported 1.3 binge eating episodes per day, ranging from 0 to 4. Participants reported an average of approximately 9 binge eating episodes per week, ranging from 2 to 17. Additionally, on days during which participants reported more than one binge eating episode, the average duration between episodes was approximately 5.25 hours, with a range of thirty minutes to approximately 14 hours. Finally, the temporal pattern of binge eating episodes across the hours of the day and days of the week was examined (see Figure 1). The frequency of binge eating episodes was highest during the early afternoon (12-3pm) and evening hours (6-9pm). Further, with regard to binge eating frequency across the days of the week, the frequency appeared to be the lowest during the weekend days.

Table 2. Binge Eating Episode Data based on ecological momentary assessment.

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge Episode Duration (mins)† | 2.00 | 154.00 | 42.21 | 34.68 |

| Time Between Binge Episodes (mins)§ | 30.00 | 833.00 | 315.78 | 169.63 |

| Binge Episodes per Day | 0 | 4 | 1.26 | 1.10 |

| Binge Episodes per Week | 2 | 17 | 8.94 | 5.06 |

Note. Data drawn from 156 total reported binge eating episodes across all subjects.

Duration data available for 118 binge eating episodes.

Time between binge eating episodes that occurred within the same day.

Figure 1. Binge Eating Episode Frequency by Time of Day and Day of Week (N = 156 episodes).

Discussion

The primary goal of the current investigation is to further examine and clarify binge eating behavior in individuals with BED, focusing primarily on duration of binge eating episodes. The results of the first study indicated that participants with BED who reported longer (i.e., greater than two hours) average binge eating episode duration displayed greater symptoms of depression and lower self-esteem compared to participants with shorter average binge durations; however, no significant differences were found between the binge episode duration groups for BMI, age, sex, or EDE global or subscale scores. The results for the second study using EMA indicated that average binge eating episode duration for BED participants was approximately 42 minutes, although the duration varied from a few minutes to over two hours. This finding in a BED sample is somewhat consistent with previous research in BN, which suggested an average binge duration of approximately one hour [3,4]. As expected for individuals with BED, binge eating was quite frequent but highly variable with an average of at least one episode per day (maximum of four episodes per day), as well as an average of nine episodes per week (maximum of 17 episodes).Further, the pattern of binge eating episodes across the hours of the day that was explored in Study 2 corresponds with past research on bulimic behavior in patients with BN [20]. Specifically, binge eating episodes seem to be most common in the early afternoon and the evening hours in both BED and BN.

Although the current findings contribute to a limited literature on duration of binge eating episodes and other features of binge eating in BED, these results should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. In the first study, given that binge eating episode duration was assessed via interviewer administered questions that were added to a well-validated semi-structured interview (i.e., the EDE), the reliability and validity of these particular items is unclear. In addition, Study 2 binge eating episodes were based on self-reported EMA data and may not have met DSM-IV criteria for objectively large binge eating episodes. Relatedly, given the self-report nature of binge duration in both studies, individuals may have differed in terms of how they distinguished between discrete eating episodes. As such, the difference between short- and long-duration binge eaters could be due to differences in whether an individual reports each eating episode as an isolated meal or “lumps” together several episodes that occur close together in time as one meal. Second, although the use of EMA to collect data on characteristics of binge eating, including duration was a strength of Study 2 given that this methodology reduces retrospective recall and other types of biases [20], the sample size was small and included individuals with full and subthreshold BED. The repeated nature of assessments in the EMA protocol allowed for data to be collected on a large number of binge eating episodes, but future studies should include larger sample sizes to the current findings. Third, the majority of participants across both studies were Caucasian and female, thus potentially limiting the generalizability of the results to more demographically heterogeneous groups. Finally, although past literature suggests the reactive effects of EMA are very minimal [21], the possibility exists that completing the momentary recordings may have impacted participant ratings of the behaviors of interest.

The findings from the current studies offer useful descriptive information regarding binge eating in individuals with BED. One potentially useful extension of these findings would be to collect data similar to the current studies in samples of both BED and BN patients. For example, it may be that binge eating in bulimia nervosa patients may be of shorter duration and typically involve the consumption of more calories than binge eating episodes in BED. However, little empirical evidence speaks to these differences, and these beliefs are not well demonstrated through empirical research. Better understanding of the clinical features of binge eating in both BN and BED, and the differences between these features, may prove informative regarding the precipitants and maintaining factors associated with binge eating in both clinical populations.

In summary, these findings suggest that the duration of binge eating episodes varies widely among individuals with BED but that the average episode is typically less than one hour and more likely to occur on weekdays than weekends. In addition, these data indicate that individuals who report longer average binge eating episode duration report higher depression and lower self-esteem scores than those with shorter average (i.e., less than two hour) binge eating episodes. The mechanisms contributing to the association between binge eating episode duration and low self-esteem and depression are unclear but warrant further investigation to determine potential implications to BED treatment and prevention.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants DK61912 and DK61973 from NIDDK, K02 MH65919 from NIMH, and a Pilot and Feasibility Grant from the Minnesota Obesity Center (MNOC; NDDIK P30 DK50456).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell JE, Pyle RL, Eckert ED. Frequency and duration of binge-eating episodes in patients with bulimia. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:835–836. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell JE, Laine DC. Monitored binge-eating behavior in patients with bulimia. Int J Eat Disord. 1985;4:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kissileff HR, Zimmerli EJ, Torres MI, Devlin MJ, Walsh BT. Effect of eating rate on binge size in bulimia nervosa. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell JE, Mussell MP, Peterson CB, Crow S, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Davis T, Weller C. Hedonics of binge eating in women with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26(2):165–170. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199909)26:2<165::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guss JL, Kissileff HR, Devlin MJ, Zimmerli E, Walsh BT. Binge size increases with BMI in women with binge-eating disorder. Obes Res. 2002;10:1021–1029. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sysko R, Devlin MJ, Walsh BT, Zimmerli E, Kissileff HR. Satiety and test meal intake among women with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:554–561. doi: 10.1002/eat.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh BT, Boudreau G. Laboratory studies of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:30–38. doi: 10.1002/eat.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greeno CG, Wing RR, Shiffman S. Binge antecedents in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B. Maintenance of binge eating through negative mood: A naturalistic comparison of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:521–530. doi: 10.1002/eat.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wegner KE, Smyth JM, Crosby RD, Wittrock D, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. An evaluation of the relationship between mood and binge eating in the natural environment using ecological momentary assessment. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:352–361. doi: 10.1002/eat.10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel SG, Kahler KA, Lystad CM, Crosby RD, Simonich HK, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Mitchell JE. Eating behavior in obese BED, obese non-BED, and non-obese control participants: a naturalistic study. Behav Res and Ther. 2009;47:897–900. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Grange D, Gorin A, Catley D, Stone AA. Does momentary assessment detect binge eating in overweight women that is denied at interview? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2001;9:309–324. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):1347–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairburn D, Cooper Z. In: The eating disorder examination Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 317–360. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. (1986). The inventory for depressive symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18:65–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Calogero RM. Ecological momentary assessment of affect, stress, and binge-purge behaviors: day of week and time of day effects in the natural environment. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:429–436. doi: 10.1002/eat.20623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farchaus Stein K, Corte C. Ecological momentary assessment of eating-disordered behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:349–360. doi: 10.1002/eat.10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]