Highlights

-

•

rHPIV3cp45 vaccine was immunogenic and well-tolerated in seronegative young children.

-

•

A second dose of rHPIV3cp45 given 6 months later was restricted in those previously infected.

-

•

Antibody responses were boosted after a second dose of rHPIV3cp45.

-

•

A second dose of rHPIV3cp45 induced antibody responses in two previously uninfected children.

Keywords: Parainfluenza, Live-attenuated vaccine, Recombinant virus vaccine, Pediatric vaccine

Abstract

Background

Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) is a common cause of upper and lower respiratory tract illness in infants and young children. Live-attenuated cold-adapted HPIV3 vaccines have been evaluated in infants but a suitable interval for administration of a second dose of vaccine has not been defined.

Methods

HPIV3-seronegative children between the ages of 6 and 36 months were randomized 2:1 in a blinded study to receive two doses of 105 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose) of live-attenuated, recombinant cold-passaged human PIV3 vaccine (rHPIV3cp45) or placebo 6 months apart. Serum antibody levels were assessed prior to and approximately 4–6 weeks after each dose. Vaccine virus infectivity, defined as detection of vaccine-HPIV3 in nasal wash and/or a ≥ 4-fold rise in serum antibody titer, and reactogenicity were assessed on days 3, 7, and 14 following immunization.

Results

Forty HPIV3-seronegative children (median age 13 months; range 6–35 months) were enrolled; 27 (68%) received vaccine and 13 (32%) received placebo. Infectivity was detected in 25 (96%) of 26 evaluable vaccinees following doses 1 and 9 of 26 subject (35%) following dose 2. Among those who shed virus, the median duration of viral shedding was 12 days (range 6–15 days) after dose 1 and 6 days (range 3–8 days) after dose 2, with a mean peak log10 viral titer of 3.4 PFU/mL (SD: 1.0) after dose 1 compared to 1.5 PFU/mL (SD: 0.92) after dose 2. Overall, reactogenicity was mild, with no difference in rates of fever and upper respiratory infection symptoms between vaccine and placebo groups.

Conclusion

rHPIV3cp45 was immunogenic and well-tolerated in seronegative young children. A second dose administered 6 months after the initial dose was restricted in those previously infected with vaccine virus; however, the second dose boosted antibody responses and induced antibody responses in two previously uninfected children.

1. Introduction

Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) is an important cause of respiratory disease in infants and young children, responsible for both upper respiratory disease as well as lower respiratory tract disease including bronchiolitis and pneumonia [1], [2]. Human parainfluenza viruses (HPIV) types 1–4 are associated with a substantial burden of disease in children overall, resulting in frequent medical care and hospitalization for pediatric respiratory disease [3]; HPIV3 alone is second only to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) for causing bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants less than 6 months of age [1]. Patients of all ages with underlying pulmonary disease or immunocompromising conditions may have serious disease related to HPIVs, with HPIV3 being the most important among these viruses [4], [5], [6]. There is currently no licensed vaccine or antiviral therapy available for the prevention or treatment of HPIV disease.

Live-attenuated HPIV3 vaccines have been developed and undergone clinical testing over the past several decades [7], [8], [9], [10]. The use of the intranasal route for administration of live-attenuated viral vaccines may offer advantages for immunization against HPIV in young children, including the potential for induction of both mucosal and systemic immunity against infection [7], [8], [9], [11]. As with live-attenuated influenza virus vaccines, more than one dose of these live-attenuated vaccines may be needed to induce sustained protection in infants and young children [9], [12].

Two approaches to development of live-attenuated HPIV3 vaccines have been taken. The related animal virus bovine PIV3 was used to create chimeric human bovine PIV3 vaccines [13], [14], [15], [16]. In addition, live-attenuated vaccine candidates from human HPIV3 strains were derived via repeated passages at low temperature [17], [18], [19], [20]. The most attenuated of these, designated cp45, was extensively evaluated in phase I and II clinical trials in children and infants as young as one month of age [8], [21], [22], [23].

More recently, a cDNA-derived recombinant version of this biologically derived vaccine was developed, designated rHPIV3cp45. The rHPIV3cp45 vaccine contains the 15 known attenuating mutations present in the biologically derived virus [24]. The use of a cDNA approach has the advantage of using a virus with a short, well-characterized passage history as well as the ability to readily regenerate and modify the virus as needed [7]. The rHPIV3cp45 vaccine was recently evaluated in a phase I trial in which infants ages 6–12 months were randomized to receive two doses of rHPIV3cp45 vaccine or placebo, administered 4–10 weeks apart [25]. While the safety profile and the infectivity of the first dose of rHPIV3cp45 were similar to that previously observed with the biologically derived virus, the second dose of vaccine was highly restricted in replication and did not boost serum antibody responses [25]. For this reason, we explored whether extending the interval between doses might enhance the infectivity and immunogenicity of a second dose of vaccine. The purpose of this study was to determine the tolerability, infectivity, and immunogenicity of two 105 TCID50 doses of rHPIV3cp45 administered 6 months apart to HPIV3 seronegative infants and children.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Vaccine

The experimental vaccine rHPIV3cp45 is a live recombinant (r)-derived attenuated human (H) PIV3 virus that is genetically and phenotypically comparable to the extensively evaluated, biologically derived HPIV3cp45 vaccine [25], the vaccine previously evaluated in infants as young as 1–2 months of age [8]. The seed virus for the production of this experimental vaccine was generated at the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases (LID), National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD. The clinical lot of vaccine virus was prepared at Charles River Laboratories (Malvern, PA). The rHPIV3cp45 clinical lot (Lot PIV3#102A) was tested for sterility, infectivity, sequence identity, safety in animals, and the presence of adventitious agents. The lot passed all tests satisfactorily. Vaccine virus was stored frozen at −70 °C and had a mean infectivity titer of 107 tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) per mL. Final vial content was diluted to dose on-site.

2.2. Study population

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outpatient trial enrolled HPIV3 seronegative subjects between the ages of 6 and 36 months who were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive 2 doses of vaccine or placebo, respectively. The ClinicalTrials.gov identifier for this study is NCT01254175. For the purpose of this study, HPIV3-seronegative was defined as a hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) serum antibody titer of <1:8 [8], [21], [23]. The study was conducted between March 2010 and June 2012 at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Immunization Research (CIR), Baltimore, MD, the Seattle Children's Research Institute (SCHRI) in Seattle, WA, and the following pediatric clinical research sites affiliated with the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT): Miller Children's Hospital, Long Beach, CA; University of California-San Diego, San Diego, CA; Rush University, Cook County Hospital, Chicago, IL; Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA; and San Juan City Hospital, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Inclusion criteria for young children participating in this trial included being in a good state of health, up-to-date on routine immunizations, and having parents or legal guardians willing and able to sign informed consent. Children were excluded from participation if they had known or suspected reactive airway disease, major congenital malformations, impaired immunological functions, were receiving immunosuppressive therapy or were recipients of a solid organ or bone marrow transplant, lived in a home environment with a young infant < 6 month of age or a severely immunosuppressed family member, had been previously immunized with HPIV3 vaccine or were known to have hypersensitivity to any vaccine component. Children born to HIV-infected women were eligible if the child was confirmed to be HIV-uninfected. Children who had a recent fever (≥100.7 °F), an acute upper respiratory illness, recent acute otitis media, received a live-attenuated routine vaccine within 4 weeks or inactivated routine vaccine within 2 weeks, received systemic steroids or antibiotics, or a history of prematurity (<37 weeks gestation) with an age < 1 year were deferred for later enrollment.

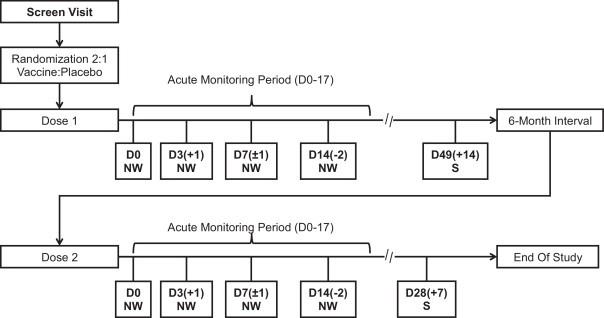

2.3. Study design

Children were screened for HPIV3 antibody within 30 days prior to enrollment. At enrollment, seronegative children were randomized to receive 2 doses of 105 TCID50 of vaccine virus or placebo (1x qualified Leibovitz L-15 medium, Lonza, Walkersville, MD) approximately 6 months apart (Fig. 1 ). Subjects were randomized 2:1 to receive 2 doses of vaccine or 2 doses of placebo using a predetermined randomization scheme assigned by the unblinded pharmacy or laboratory dispenser. A volume of 0.5 mL of vaccine or placebo was delivered via nose drops (0.25 mL per nostril) by a blinded study nurse using a sterile, needle-less syringe while the subject was supine. Immediately after dosing, subjects remained supine for approximately 60 s and were observed for adverse events for 30 min.

Fig. 1.

The study design is depicted below. All vaccine recipients who participated in dose 2 of the study, received vaccine for dose 2. All placebo recipients received placebo for both dose 1 and dose 2. Abbreviations: D = study day; NW = collection of nasal wash; S = blood draw for collection of sera.

Serum was collected prior to the first dose, immediately prior to the second dose, and 4–6 weeks after the second dose. Nasal washes were performed prior to inoculation (day 0) and on days 3(+1), 7(±1), and 14(−2) following inoculation for each dose. As described below, the infectivity and phenotypic stability of the vaccine virus were assessed at each study visit from collected nasal wash specimens.

All subjects were monitored for 17 days following each inoculation for respiratory or febrile illnesses [25], with additional physical examination and nasal wash collection in the event of respiratory or febrile illness. Parents and study staff monitored temperature daily using the Phillips Sensor Touch ® thermometer, a temporal artery thermometer, to screen for elevated temperatures [26]. Any temporal temperature ≥100 °F was verified by obtaining rectal temperatures within 20 min using standard thermometers provided by the study. Prior to immunization and when illness symptoms were reported, nasal washes were obtained and tested for adventitious agents by viral culture and/or rRT-PCR testing (Fast-track Diagnostics, Luxembourg). Lower respiratory tract infections (LRIs), defined as confirmed wheezing, rales, pneumonia, croup, or rhonchi, or radiologic evidence of pneumonia, were categorized as serious adverse events, regardless of severity.

2.4. Clinical trial oversight

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of study participants prior to screening and enrollment. These studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the standards of Good Clinical Practice (as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization). This study was performed under the NIAID-held investigational new drug application BB-IND#12592 and was reviewed by the US Food and Drug Administration. The clinical protocols, consent forms, and investigator-brochures were developed by CIR, SCHRI, IMPAACT, and NIAID investigators, and were reviewed and approved by each institution's respective institutional review boards as well as the NIAID Regulatory Compliance and Human Subjects Protection Branch (RCHSPB). Clinical data were regularly reviewed by clinical and NIAID investigators and by the Data Safety Monitoring Board of the NIAID Division of Clinical Research.

2.5. Isolation and quantitation of vaccine virus

Nasal washes were performed using a sterile nasal bulb syringe and 15–20 mL of lactated Ringer's solution instilled into the child's nares. Aliquots of nasal washes were snap frozen in sucrose-phosphate-glutamate viral transport medium as previously described (8) and stored at −80 °C. For primary virus isolation and quantitation, an aliquot of each nasal wash was rapidly thawed and inoculated onto LLC-MK2 cells and incubated at 32 °C at the CIR laboratory [8], [27]. Titers of vaccine virus are expressed as tissue-culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) per mL of nasal wash fluid, with a lower limit of detection of 100.6 TCID50/mL.

2.6. Genotypic characterization of vaccine virus

To differentiate between infection with rHPIV3cp45 vaccine virus and intercurrent natural infection with wild-type (wt) HPIV3, nucleotide sequencing was performed on isolates obtained at the peak of virus shedding from all children who shed HPIV3 after either dose of vaccine. Virus isolates were produced by inoculating nasal wash onto LLC-MK2 cells and harvesting the supernatant 6–7 days later. Viral RNA was extracted using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and cDNA was generated using Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For each sample, cDNA was amplified with the Clontech Advantage HF 2 PCR Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) to generate a PCR product covering a segment of the F gene (nucleotides 5000-7251) that contains two attenuating mutations in rHPIV3cp45 (encoding Ile-420 to Val and Ala-450 to Thr). DNA was purified using the High Pure PCR Product Purification kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Sequencing was performed using ABI Big-Dye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI3730 sequencer.

2.7. Detection of adventitious viral agents

Nasal wash specimens obtained just prior to inoculation, on days 3 (range 3–4 days), 7 (range 6–8 days), and 14 (range 12–14 days), and at the time of any respiratory or febrile illness were tested for adventitious viral agents either by viral culture [8], [27] or by reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction assay (rRT-PCR; Fast-track Diagnostics, Luxembourg). Tested adventitious agents included the following: coronavirus, adenovirus, enterovirus, parechovirus, respiratory syncytial virus A/B, parainfluenza viruses types 1–4, human metapneumovirus A/B, bocavirus, and mycoplasma pneunominae.

2.8. Antibody assays

Serum specimens were stored frozen until use. Sera were tested for HPIV3 antibody by the HAI antibody test method, starting at a serum dilution to 1:4, with 2-fold dilution increments and endpoint titration [25].

2.9. Data analysis

Infection with vaccine virus was defined as either the isolation of vaccine virus or a ≥ 4-fold rise in antibody titer [25]. The mean peak titer of vaccine virus shed (log10 TCID50/mL) and duration (last day) of shedding were calculated for infected vaccinees only. Data were analyzed using Stata 12.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX). HAI-reciprocal titers were transformed to log2 values for calculation of mean log2 titers, and Student's t test was used to compare HAI titers between groups. Baseline data and illness rates between the groups were compared using independent sample unequal variance t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables.

3. Results

3.1. Population

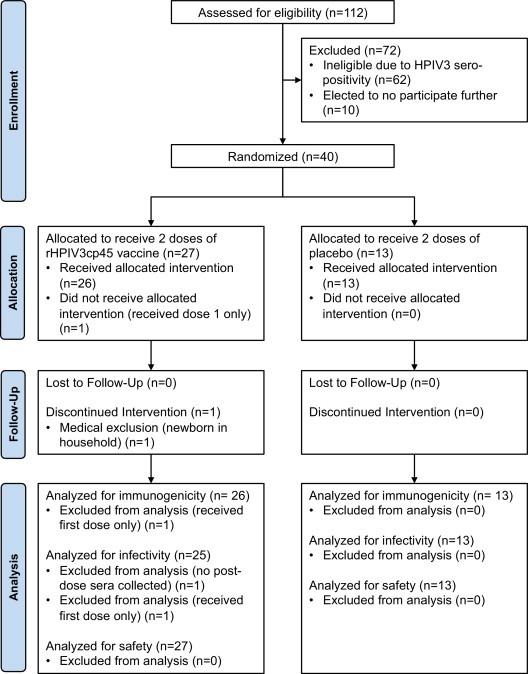

A total of 40 infants and young children were enrolled into this study (Fig. 2 ), with a median age of 13 months (range 6–35 months). The 27 (68%) subjects randomized to receive vaccine received the first dose at a median age of 13 months (range 6–35 months), and 26 (67%) received the second dose at a median age of 18 months (range 12–40 months). The 13 placebo recipients received the first and second doses at a median age of 16 months (range 6–29 months) and 23 months (range 13–34 months), respectively. There were no significant differences in age at vaccination, gender, racial, and ethnic profiles between vaccine and placebo groups (Table 1 ). Thirty-nine (98%) subjects received two doses of vaccine (n = 26) or placebo (n = 13). Thirty-nine (98%) had a blood sample obtained following the first vaccine dose and second vaccine dose. The median duration of participation for each subject was 28 weeks (range 26–32 weeks). Study follow-up was excellent, with only one subject lost to follow-up.

Fig. 2.

CONSORT participant flow diagram.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of infants and children enrolled in the study.

| Median age, months (range) | Vaccine (n = 27) | Placebo (n = 13) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose 1 (n = 40) | 13 (6–35) | 16 (6–29) | 0.34 |

| Dose 2 (n = 39) | 18 (12–40) | 23 (13–34) | 0.27 |

| Male, no (%) | 17 (63) | 7 (54) | 0.73 |

| Race, no (%) | |||

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0.33 |

| Black | 9 (32) | 3 (23) | 0.72 |

| Caucasian | 14 (50) | 9 (69) | 0.33 |

| Multi-racial/unknown | 4 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.28 |

| Hispanic, no (%) | 9 (33%) | 2 (15%) | 0.29 |

3.2. Vaccine safety and reactogenicity

The rHPIVcp45 vaccine was well tolerated by the study subjects. No serious adverse events related to study vaccine were reported in any subject; specifically, no lower respiratory tract disease or other respiratory illnesses requiring medical attention considered to be related to study vaccine occurred throughout the trial. Rates of fever did not differ significantly between vaccine and placebo groups following either dose 1 or dose 2 of study drug, with rates similar and < 15% in both vaccine and placebo groups following each vaccine dose (Table 2 ). Mild upper respiratory signs and symptoms were common following both dose 1 and 2 of vaccine and placebo (Table 2), but cough was uncommon, occurring only in 3 (11%) vaccine recipients after the first dose of vaccine. Otitis media was documented following the first dose of study drug in one (4%) vaccine recipient (first documented on day 15) and one (8%) placebo recipient (first documented on day 18). Rates of illness did not differ significantly following the first or second dose of vaccine and were similar in vaccine and placebo recipients (P = 0.73 and 0.71, respectively for dose 1 and dose 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and virologic responses of infants and children following rHPIV3cp45 or placebo.

| Dose 1 |

P-value | Dose 2 |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Placebo | Vaccine | Placebo | |||

| Total subjects (N) | 27 | 13 | 26 | 13 | ||

| Subjects with sera collected (N) | 26 | 13 | 26 | 13 | ||

| N (%) of evaluable infecteda | 25/26 (96) | 3/13 (23) | <0.001 | 9/26 (35) | 0 (0) | 0.018 |

| N (%) of evaluable shedding vaccine virus | 24/27 (89) | 0/13 (8) | <0.001 | 9/26 (35) | 0 (0) | 0.018 |

| Median days of shedding (range)b | 12 (6–15) | N/A | – | 6 (3–8) | N/A | – |

| Mean peak viral titer in log10 TCID50/mLc (SD) | 3.4 (1.0) | – | – | 1.5 (0.92) | – | – |

| N (% of subjects with sera) with 4-fold rise in antibody titer | 23 (88) | 3 (23) | <0.001 | 6 (23) | 0 (0) | 0.081 |

| Median log2-fold change in HAI antibody titer (range) | 5 (0–7) | 0 (0–6) | <0.001 | 0 (−1 to 5) | 0 (0–0) | 0.017 |

| N patients with illness (%) | ||||||

| Fever | 3 (11) | 2 (15) | 1.00 | 3 (12) | 1 (8) | 1.00 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 9 (33) | 4 (31) | 1.00 | 7 (27) | 2 (15) | 0.689 |

| Rhinorrhea | 9 (33) | 4 (31) | 1.00 | 7 (27) | 2 (15) | 0.69 |

| Pharyngitis | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0.33 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Cough | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.538 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Otitis media | 1 (4) | 1 (8) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Any respiratory or febrile illness | 11 (41) | 4 (31) | 0.730 | 9 (35) | 3 (23) | 0.714 |

Infection was defined as vaccine virus isolation and/or ≥4-fold rise in serum antibody titer.

Duration of shedding was calculated for infected subjects only, and was defined as the time between inoculation and the last day on which vaccine virus was recovered.

Mean peak titer of virus shed was calculated for infected subjects only.

Nasal washes obtained from participants were tested for adventitious agents on day 0 prior to vaccination with study drug. Nasal washes were also obtained and tested for potential adventitious agents in 15 symptomatic subjects (11 vaccine recipients; 4 placebo recipients) following dose 1 and in 12 symptomatic subjects (9 vaccine recipients; 3 placebo recipients) following dose 2 (Table 2). Viruses other than rHPIV3cp45 were detected in 14/27 (52%) vaccine recipients following dose 1 of vaccine and 7/26 (27%) following dose 2. Viruses other than rHPIV3 were detected in 5/13 (38%) placebo recipients after both dose 1 and dose 2. Viruses other than rHPIV3cp45 were identified in 25 nasal wash specimens following dose 1, and 17 nasal wash specimens following dose 2. The most common adventitious agent detected throughout the study was rhinovirus: 7/40 (17.5%) with dose 1 and 6/39 (15.4%) with dose 2. Noted adventitious agents detected in both vaccinees and placebo recipients throughout the study included adenoviruses, bocaviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, HPIV1 and 4, and rhinoviruses.

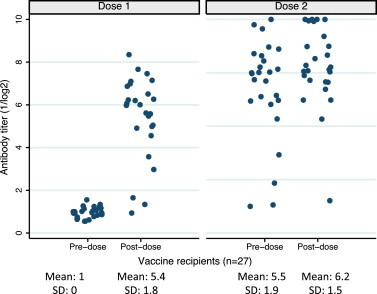

3.3. Infectivity and Immunogenicity of rHPIV3cp45

Shedding of vaccine virus was documented in 24 of 27 (89%) children following the first dose of vaccine and 9 of 26 (35%) following the second dose (P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median duration of viral shedding in those infected with vaccine virus was 12 days (range 6–15 days) following the first dose compared with 6 days (range 3–8 days) following the second dose of vaccine, with the peak mean log10 titer following the first dose of 3.4 PFU/mL (SD 1.0) compared to 1.5 PFU/mL (SD 0.92) following the second dose (P < 0.001). A 4-fold or greater increase in serum antibody was documented in 23 of 26 (88%) evaluable children following the first dose of vaccine, with a mean log2 HAI antibody titer of 5.3 ± 1.8, and in six of 26 (23%) children following the second dose, with a mean log2 antibody titer of 6.2 ± 1.5. At the time of the first dose of vaccine, the age of vaccine recipients who were infected after dose 1 [13.9 months (SD: 1.53)] was significantly older than those who were infected after dose 2 [9.1 months (SD 0.61)] (P = 0.007). Among vaccine recipients (n = 26), those with higher pre-dose antibody titers were less likely to shed virus (P = 0.03). The mean pre-dose 2 antibody titer in those who did not shed virus (n = 17) was 6.1 (SD 1.6), as compared to the mean pre-dose 2 antibody titer in those who did shed virus [(n = 9; mean viral antibody titer 4.3 (SD 2.1)].

HPIV3 was detected in one placebo recipient beginning on day 0 of the study, prior to vaccination. This isolate was confirmed by RT-PCR amplification and sequence analysis to be wild type HPIV3 and not vaccine virus. In addition, vaccine virus was isolated from nasal wash samples of each vaccinee that shed (n = 33; 24 after does 1, 9 after dose 2) and confirmed to be vaccine virus by RT-PCR and sequencing. Isolates from all of the vaccinees contained the expected rHPIV3cp45 mutations (data not shown), thus confirming that the virus was vaccine derived, and that the attenuating mutations were maintained during vaccine virus replication.

Antibody responses following each vaccine dose are shown in Fig. 3 . The majority of study participants (23/26, 88%) had a 4-fold or greater antibody rise following the first dose of vaccine. No subject had a 4-fold rise in titers to indicate natural infection between dose 1 and dose 2. While the mean log2 antibody titer did not increase significantly for the entire group of vaccinees after the second vaccine dose, ≥4-fold increases in titer were observed for 4 of the 5 children who had a log2 antibody titer of ≤4 following the first dose of vaccine. Thus, the net effect of the second dose was to increase the proportion of subjects achieving relatively high HAI antibody titers: whereas only 15 children achieved post-vaccination log2 titers >6 observed following the first dose of vaccine, 21 achieved log2 titers >6 following the second dose. Only one evaluable vaccine recipient had neither seroconversion nor viral shedding documented. Overall infectivity, defined as either viral shedding or a ≥4-fold rise in antibody titer, was observed in 25 of 27 (93%) of vaccinated children following the first dose and 9 of 26 (35%) following the second dose of vaccine. Three (23%) placebo recipients had a ≥ 4-fold rise in HAI antibody titers four to six weeks following the first dose of vaccine, including the child who shed wt HPIV3.

Fig. 3.

Reciprocal HAI antibody levels before and after dose 1 and dose 2 for all individual vaccine recipients.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether increasing the interval between doses was able to enhance the infectivity of a second dose of rHPIV3cp45. The results of this study confirmed our initial experience with rHPIV3cp45 [25]: the vaccine was safe and well-tolerated with good rates of infectivity and antibody response following a single dose of vaccine. We demonstrated that children with a substantial antibody response following the first dose of vaccine did not seem able to be either infected or boosted when a second dose was administered approximately 6 months after the first dose. In contrast, the second dose of vaccine given six months later appeared to boost antibody titers in those with a suboptimal response following the first dose, and it was associated with lower amounts of detectable virus in the nasal wash. Of interest, children who required a second dose of vaccine to achieve an antibody response were significantly younger than those who did not. Overall, this study demonstrated that two doses separated by 6 months are able to infect children under three years of age who were not infected with a single dose of vaccine.

As expected for a pediatric trial, high rates of infections and symptoms with other viruses were common, but rates and types of viruses and symptoms were similar between placebo and vaccine groups, emphasizing the need for placebo-controlled trials. The detection of adventitious agents using molecular diagnostic techniques was helpful in assessing potential causality of fever in subjects in this trial, since many of both placebo and vaccine recipients had fever associated with infection with other viruses during the trial. Since HPIV3 typically circulates during the spring and summer months when these trials are conducted, sequence analysis proved a useful tool for differentiating between infection with wt and vaccine virus. This technology is important in assessing the safety and reactogenicity of vaccines and the conduct of clinical trials: illness in a placebo recipient was able to be directly related to infection with wtHPIV3 and not to potential spread of vaccine virus in the clinic setting.

Previous clinical studies with similar HPIV 3 vaccines have shown good immunogenicity. For example, the 2003 study by Karron et al. in adults, children, and infants revealed 82–100% infectivity of a single dose in seronegative children between the ages of 6–36 months using a dose of either 104 or 105 [8]. A later study by Bernstein et al. studied the recombinant HPIV3 vaccine utilized in our clinical trial, rHPIV3cp45, in infants 6 to less than 12 months of age with 3 doses of vaccine at a dose of 105 [10]. In this younger population, viral shedding after dose 1 was documented in 85% of recipients compared with 89% in our older population. After 3 doses in the Bernstein trial, either seroresponse or shedding occurred in 95% of vaccine recipients compared with our rate of infectivity (seroresponse or shedding) in 96% after dose 1 and 93% after dose 2.

Future use of this vaccine may include immunization of young infants, potentially with repeated dosing to ensure optimal immunogenicity. Since the youngest children are at highest risk for hospitalization or receiving medical care, this group would be the natural targets for immunization to provide the most protection against disease. In addition, use of rHPIV3cp45 in combination with live-attenuated RSV and human metapneumovirus (HMPV) vaccines can be envisioned as a strategy to provide broad protection against important respiratory viral pathogens of infancy and early childhood [18]. A dosing schedule for this type of vaccine would need to be harmonized with current pediatric vaccination schedules.

Acknowledgements

The study team gratefully acknowledges the contributions of families participating in this study, as well as supporting physicians, nurses, and research staff at Seattle Children's Clinical Research Center, North Seattle Pediatrics, and Woodinville Pediatrics.

The team wishes to thank the Division of Clinical Research, especially the RCHSPB members, and the Division of AIDS, both NIAID, for their support and oversight of the study. Sonia Surman, LID/NIAID, was responsible for characterization and sequencing of virus isolates.

Financial support: This study was funded by the Intramural Research program of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Clinical trials were conducted as part of contracts between NIAID and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (HSN272200900010C). In Seattle, this project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1RR025014. Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C). Conflict of interest: No conflicts of interests or financial disclosures are reported by any authors. A. Schmidt is currently an employee of GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix A. P1096 site acknowledgements

Members of the P1096 Protocol Team include: Janet A. Englund, MD, Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA; Ruth A. Karron, MD, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD; Coleen K. Cunningham, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Phillip LaRussa, MD, Columbia University IMPAACT CRS, New York, NY; Ann J. Melvin, MD, MPH, Seattle Children's Hospital CRS, Seattle, WA; IL; Ed Handelsman, MD, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD; Peter L. Collins, PhD, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; Alexander C. Schmidt, MD, PhD, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; Linda Marillo, BA, Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Buffalo, NY; Elizabeth Petzold, PhD, Social and Scientific Systems, Silver Spring, MD; Paul Sato, MD, MPH, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD; George K. Siberry, MD, MPH, Pediatric Adolescent and Maternal AIDS Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, Bethesda, MD; Joycelyn Thomas, BSN, RN, Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA; Joan Dragavon, M.L.M., University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98104.

Participating sites and site personnel include: 4001 Chicago Children's CRS (Pam Sroka, BSN; Laura Fern, RN; Lynn Heald, PNP; Laurie Strotman, APN); 4601 UCSD IMPAACT CTU (Rolando Viani, MD, MTP; Stephen A Spector, MD; Jeanne M Manning, RN, BSN; Anita Darcey, RN); 5083 Rush University Cook County Hospital Chicago NICHD CRS (Latania Logan, MD; Mariam Aziz, MD; Maureen McNichols, RN, MSN, CCRC; James Mcauley, MD, MPH); 5017 Seattle Children's Hospital CRS (Lisa Frenkel, MD; Corry Venema-Weiss, ARNP; Joycelyn Thomas, RN; Jenna Lane ARNP; National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000423); 5031 San Juan City Hospital PR NICHD CRS (Midnela Acevedo-Flores, MD; Nicolas Rosario, MD, PD MSc; Lourdes Angeli-Nieves, RN, MPH; Dalila Guzmán-Lluberes, RPh); 4101 Columbia University IMPAACT CRS (Gina Silva, RN; Seydi Vazquez, RN; Andrea Jurgrau, CNP); 4701 Duke Pediatric Infectious Diseases (John Swetnam, M.Ed; Mary Jo Hassett, RN; Joan Wilson, RN; Julia Giner, RN); 5093 Miller Children's Hospital Long Beach CA. Research personnel at Seattle Children's Hospital included Diane Kinnunen, BSN, Kirsten Lacombe, BSN, and Catherine Bull, ARNP.

References

- 1.Glezen W.P., Frank A.L., Taber L.H., Kasel J.A. Parainfluenza virus type 3: seasonality and risk of infection and reinfection in young children. J Infect Dis. 1984;150(6):851–857. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanock R.M., Murphy B.R., Collins P.L. Parainfluenza viruses. In: Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., Griffin D.E., Lamb R.A., Martin M.A., Roizman B., editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 1341–1379. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberg G.A., Hall C.B., Iwane M.K., Poehling K.A., Edwards K.M., Griffin M.R. Parainfluenza virus infection of young children: estimates of the population-based burden of hospitalization. J Pediatr. 2009;154(5):694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glezen W.P., Greenberg S.B., Atmar R.L., Piedra P.A., Couch R.B. Impact of respiratory virus infections on persons with chronic underlying conditions. JAMA. 2000;283(4):499–505. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peck A.J., Englund J.A., Kuypers J., Guthrie K.A., Corey L., Morrow R. Respiratory virus infection among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: evidence for asymptomatic parainfluenza virus infection. Blood. 2007;110(5):1681–1688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-060343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg A., Lyu D.M., Li S., Marquesen J., Zamora M.R. Incidence and morbidity of human metapneumovirus and other community-acquired respiratory viruses in lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2010;12(4):330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt A.C. Progress in respiratory virus vaccine development. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32(4):527–540. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karron R.A., Belshe R.B., Wright P.F., Thumar B., Burns B., Newman F. A live human parainfluenza type 3 virus vaccine is attenuated and immunogenic in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(5):394–405. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000066244.31769.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt A.C., Schaap-Nutt A., Bartlett E.J., Schomacker H., Boonyaratanakornkit J., Karron R.A. Progress in the development of human parainfluenza virus vaccines. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5(4):515–526. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein D.I., Falloon J., Yi T. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a study of the safety and immunogenicity of a live, attenuated human parainfluenza virus type 3 vaccine in healthy infants. Vaccine. 2011;29(40):7042–7048. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durbin A.P., Karron R.A. Progress in the development of respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus vaccines. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(12):1668–1677. doi: 10.1086/379775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrose C.S., Wu X., Knuf M., Wutzler P. The efficacy of intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine in children 2 through 17 years of age: a meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled studies. Vaccine. 2012;30(5):886–892. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karron R.A., Wright P.F., Hall S.L., Makhene M., Thompson J., Burns B.A. A live attenuated bovine parainfluenza virus type 3 vaccine is safe, infectious, immunogenic, and phenotypically stable in infants and children. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(5):1107–1114. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karron R.A., Thumar B., Schappell E., Surman S., Murphy B.R., Collins P.L. Evaluation of two chimeric bovine-human parainfluenza virus type 3 vaccines in infants and young children. Vaccine. 2012;30(26):3975–3981. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg D.P., Walker R.E., Lee M.S., Reisinger K.S., Ward J.I., Yogev R. A bovine parainfluenza virus type 3 vaccine is safe and immunogenic in early infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(7):1116–1122. doi: 10.1086/428092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt A.C., McAuliffe J.M., Huang A., Surman S.R., Bailly J.E., Elkins W.R. Bovine parainfluenza virus type 3 (BPIV3) fusion and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase glycoproteins make an important contribution to the restricted replication of BPIV3 in primates. J Virol. 2000;74(19):8922–8929. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8922-8929.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez M., Mufson M.A., Dubovsky F., Knightly C., Zeng W., Losonsky G. Phase-I study MEDI-534, of a live, attenuated intranasal vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza-3 virus in seropositive children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(7):655–658. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318199c3b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belshe R.B., Newman F.K., Tsai T.F., Karron R.A., Reisinger K., Roberton D. Phase 2 evaluation of parainfluenza type 3 cold passage mutant 45 live attenuated vaccine in healthy children 6–18 months old. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(3):462–470. doi: 10.1086/381184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crookshanks F.K., Belshe R.B. Evaluation of cold-adapted and temperature-sensitive mutants of parainfluenza virus type 3 in weanling hamsters. J Med Virol. 1984;13(3):243–249. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890130306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crookshanks-Newman F.K., Belshe R.B. Protection of weanling hamsters from experimental infection with wild-type parainfluenza virus type 3 (para 3) by cold-adapted mutants of para 3. J Med Virol. 1986;18(2):131–137. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890180205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belshe R.B., Newman F.K., Anderson E.L., Wright P.F., Karron R.A., Tollefson S. Evaluation of combined live, attenuated respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza 3 virus vaccines in infants and young children. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(12):2096–2103. doi: 10.1086/425981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madhi S.A., Cutland C., Zhu Y., Hackell J.G., Newman F., Blackburn N. Transmissibility, infectivity and immunogenicity of a live human parainfluenza type 3 virus vaccine (HPIV3cp45) among susceptible infants and toddlers. Vaccine. 2006;24(13):2432–2439. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karron R.A., Wright P.F., Newman F.K., Makhene M., Thompson J., Samorodin R. A live human parainfluenza type 3 virus vaccine is attenuated and immunogenic in healthy infants and children. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(6):1445–1450. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skiadopoulos M.H., Surman S., Tatem J.M., Paschalis M., Wu S.L., Udem S.A. Identification of mutations contributing to the temperature-sensitive, cold-adapted, and attenuation phenotypes of the live-attenuated cold-passage 45 (cp45) human parainfluenza virus 3 candidate vaccine. J Virol. 1999;73(2):1374–1381. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1374-1381.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karron R.A., Casey R., Thumar B., Surman S., Murphy B.R., Collins P.L. The cDNA-derived investigational human parainfluenza virus type 3 vaccine rcp45 is well tolerated, infectious, and immunogenic in infants and young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(10):e186–e191. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822ea24f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siberry G.K., Diener-West M., Schappell E., Karron R.A. Comparison of temple temperatures with rectal temperatures in children under two years of age. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2002;41(6):405–414. doi: 10.1177/000992280204100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karron R.A., Makhene M., Gay K., Wilson M.H., Clements M.L., Murphy B.R. Evaluation of a live attenuated bovine parainfluenza type 3 vaccine in two- to six-month-old infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15(8):650–654. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]