Abstract

Approximately 15% of foster kittens die before 8 weeks of age, with most of these kittens demonstrating clinical signs or postmortem evidence of enteritis. While a specific cause of enteritis is not determined in most cases, these kittens are often empirically administered probiotics that contain enterococci. The enterococci are members of the commensal intestinal microbiota but also can function as opportunistic pathogens. Given the complicated role of enterococci in health and disease, it would be valuable to better understand what constitutes a “healthy” enterococcal community in these kittens and how this microbiota is impacted by severe illness. In this study, we characterized the ileum mucosa-associated enterococcal community of 50 apparently healthy and 50 terminally ill foster kittens. In healthy kittens, Enterococcus hirae was the most common species of ileum mucosa-associated enterococci and was often observed to adhere extensively to the small intestinal epithelium. These E. hirae isolates generally lacked virulence traits. In contrast, non-E. hirae enterococci, notably Enterococcus faecalis, were more commonly isolated from the ileum mucosa of kittens with terminal illness. Isolates of E. faecalis had numerous virulence traits and multiple antimicrobial resistances. Moreover, the attachment of Escherichia coli to the intestinal epithelium was significantly associated with terminal illness and was not observed in any kitten with adherent E. hirae. These findings identify a significant difference in the species of enterococci cultured from the ileum mucosa of kittens with terminal illness compared to the species cultured from healthy kittens. In contrast to prior case studies that associated enteroadherent E. hirae with diarrhea in young animals, these controlled studies identified E. hirae as more often isolated from healthy kittens and adherence of E. hirae as more common and extensive in healthy kittens than in sick kittens.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 74 million pet (1) and ∼70 million feral (National Geographic News report [see http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0907_040907_feralcats.html]) cats currently reside in the United States. Population projections estimate that these cats give birth to roughly 180 million kittens per year (Feral Cat Spay/Neuter Project report [see www.feralcatproject.org]). Each year inestimable numbers of kittens are abandoned, orphaned, or relinquished shortly after birth to be fostered by 4,000 to 6,000 U.S. animal shelters (Humane Society of the United States report, www.humanesociety.org). While the exact statistics are unknown, ∼15% of kittens fostered by these shelters die or are euthanized because of illness before they reach 8 weeks of age (2–6). An obvious cause of illness is unknown in as many as 20% of these kittens (3); however, the majority of them are reported to have clinical signs of diarrhea (3, 7) or postmortem evidence of enteritis at the time of death (8).

Many infectious agents are known or suspected causes of gastrointestinal morbidity in young kittens. Bacterial culprits, however, are difficult to decipher as they reside among a large and diverse enteric microbiome. The Gram-positive enterococci are an important part of the enteric microbiome and are generally considered to be gastrointestinal commensals. Enterococcus faecium in particular is commonly administered as a probiotic to kittens having diarrhea (9, 10). However, several other strains of E. faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are recognized as serious potential pathogens. The clinical importance of these enterococci is largely attributed to their ability to (i) acquire multiple antimicrobial resistance (11), (ii) opportunistically infect tissues outside the gastrointestinal tract (12–14), and (iii) form resilient environmental biofilms (15, 16).

While the clinical significance of enterococci in extragastrointestinal and nosocomial infections is well recognized, little is known about whether enterococci also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of disease inside the gastrointestinal tract. In recent years certain enterococci, most notably Enterococcus hirae and Enterococcus durans, have been observed in numerous different species of neonatal animals to intimately and extensively colonize the mucosal surface of the small intestine in a manner similar to that of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) (17–25). While most of these reports describe animals having concurrent signs of diarrhea, the association of enteroadherent enterococci with clinical disease of the gastrointestinal tract in these young animals remains unclear.

Given the conflicting roles of enterococci as both members of the commensal microbiota and opportunistic pathogens, a better understanding is needed of what constitutes the “healthy” enterococcal community in very young kittens and how this microbiota is impacted by severe illness in this population. This is particularly true with regard to the small intestine, where commensal microbial-intestinal epithelial cell interactions can have a profound impact on gastrointestinal function, colonization resistance, and presumably neonatal survival. Consequently, the purpose of the present study was to determine the prevalence, species diversity, virulence traits, clonality, and antibiotic resistance of the mucosa-associated enterococcal community of the small intestines of very young kittens and their associations with disease mortality. In addition, the prevalence and identity of enteroadherent bacteria in the small intestines of these kittens were determined in situ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study populations.

One hundred unrelated kittens ≤12 weeks of age were obtained from two collaborating facilities over a period of 18 months: fifty kittens in apparent good health and euthanized due to overpopulation at a local animal control facility (group A) and fifty kittens that had died or were euthanized due to severe illness while under foster care at a local county Society for Protection and Care of Animals (SPCA) (group B). No kittens were euthanized for the purpose of this study. Demographic information was obtained for each kitten and premortem clinical signs were used to categorize group B kittens as having primarily gastrointestinal, respiratory, or other/unknown underlying disease. Immediately postmortem, kittens were kept refrigerated at 4°C and later transported on ice packs from each collaborating facility to the North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine for the procurement of study samples.

Light microscopic examination for enteroadherent bacteria and gastrointestinal pathology.

Single full-thickness samples of the stomach, duodenum, ileum, and colon were obtained from each kitten and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for a period of ≥24 h prior to processing into paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 5-μm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Gram stains using routine methods. All tissues from each kitten were examined independently by means of light microscopy by two study investigators (P.M. and J.L.G.). Each investigator, blinded to the origin and disease state of the kittens, assessed samples for the presence of colonies of bacteria that were intimately associated with the brush border of the intestinal epithelium, as has been described in all prior reports of enteroadherent enterococcal infections (17–25). This characteristic light microscopy finding has been shown in representative specimens to correlate with the observation of filamentous projections between the enterococci and epithelial microvilli using transmission electron microscopy (21–23, 25). The final determination of enteroadherent bacterial infection in each sample was reached by consensus. All tissues from each kitten were additionally examined by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (P.M.) for the presence of histopathological lesions consistent with gastrointestinal disease.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples from kittens with light microscopic evidence of enteroadherent bacteria were sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm, mounted on poly-l-lysine-coated slides, and processed for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as previously described in detail (25, 26). Hybridizations were performed using the universal eubacterial probe Eub338 (26), labeled at the 3′ end with 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM), and subsequently examined using a specific probe directed against E. coli/Shigella (5′-Cy3-GCAAAGGTATTAACTTTACTCCC-3′) (26) or Enterococcus spp. (Enc221) (5′-Cy3-CACCGCGGGTCCATCCATCA-3′) (27) at working strengths of 5 ng/μl (26) as previously described (25, 26). Positive control slides for E. coli included formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded intestinal tissues from a pig and a dog that were diagnosed with enteropathogenic E. coli based on light microscopic observation of palisades of Gram-negative bacteria adhering to the intestinal epithelium, positive fecal culture for E. coli, and PCR amplification of the enterocyte attaching and effacing gene (eae). Positive control slides for Enterococcus spp. were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded intestinal tissue samples from a pig that was diagnosed with enteroadherent Enterococcus infection based on light microscopic observation of palisades of Gram-positive bacteria extensively colonizing the mucosal surface as previously described in this species (19, 20). For each kitten identified with enteroadherent enterococci, the enterococci were semiquantitatively described on the basis of the number of bacteria present (scant, mild, moderate, or severe) and extent of colonization of the epithelium (focal or diffuse).

DNA extractions from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded intestinal tissue.

In order to identify the species of adherent enterococci as observed by light microscopy and FISH, DNA was extracted from each corresponding paraffin-embedded tissue block. Fifteen 5-μm serial sections of each block were microwaved at 5-s intervals in 200 μl buffer ATL (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) until the paraffin liquefied. The solution was centrifuged (150 × g for 10 min), and the paraffin ring was removed using a sterile pipette tip. DNA extraction from the remaining solution was performed as previously described (25). Extractions performed concurrently with the feline samples included paraffin wax spiked with in vitro cultured E. hirae ATCC 8043 (positive control) and extraction reagents alone (negative control). Between each tissue block, an equivalent amount of paraffin was excised from a block devoid of tissue to assess for the possibility of cross-contamination between samples.

PCR identification of enteroadherent enterococci and enteropathogenic E. coli.

Samples of DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded intestinal tissue as well as paraffin blocks devoid of tissue (negative controls) were first subjected to PCR amplification of an approximately 400-bp gene sequence of feline glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) DNA as previously described (28). Subsequent PCR was performed using species-specific primer pairs for mur-2 (E. hirae) (29), ddl (E. faecium and E. faecalis) (30–32), and eae (EPEC) (33) using previously published reaction conditions (30–33). Amplicons were visualized by UV illumination after electrophoresis of 10 μl of the reaction solution in a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. The identity of each reaction product was confirmed by sequence analysis (Genewiz, Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC). Positive controls included E. hirae (ATCC 8043), E. durans (ATCC 6056), E. faecalis and E. faecium (gifts from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory at North Carolina State University), and eae-positive E. coli (a gift from Karen Post, North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory System).

Transmission electron microscopy.

Intestinal tissue specimens (∼80 mg), corresponding in location to the sites of microscopically observed enteroadherent E. hirae, were cut from the original paraffin blocks of specimens from two kittens and processed for transmission electron microscopy as previously described (25).

Isolation and identification of enterococci.

During necropsy of each kitten, the distal ileum was opened longitudinally and an area of the surface mucosa devoid of visual debris was rubbed with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator prior to streaking onto Columbia agar with colistin and nalidixic acid (CNA) containing 5% sheep blood (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD). Individual catalase-negative colonies (range, 1 to ≥10 per kitten) were subcultured onto Trypticase soy agar containing 5% sheep blood (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD). Isolates were frozen in 2× brain heart infusion broth plus 50% glycerol prior to shipment on dry ice to Kansas State University. Isolates were subsequently selected on m-Enterococcus agar (Difco, BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) and confirmed at the genus level by the esculin hydrolysis test using Enterococcosel broth (Difco, BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) incubated at 44.5°C for 24 h (34). Multiplex PCR was used to identify four common species, E. faecalis, E. faecium, Enterococcus casseliflavus, and Enterococcus gallinarum (30). Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 19433, E. faecium ATCC 19434, E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788, and E. gallinarum ATCC 49579 were used as positive controls. PCR amplification and sequencing of the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) were carried out for isolates that were not identified by multiplex PCR (35).

Screening for virulence traits by genotype and phenotype.

Multiplex PCR was performed to screen the identified isolates for four putative virulence determinants (gelE, gelatinase; cylA, cytolysin; asa1, aggregation substance; and esp, enterococcal surface protein) (36). In addition, E. hirae-specific primer sets for the virulence genes gelE, cylA, and asa1 were used to screen a subset of 60 E. hirae isolates from healthy kittens and 51 E. hirae isolates from sick kittens (37). E. faecalis MMH 594 and E. hirae AA-1c and Aa-3B were used as positive controls. Gelatinase activity was tested on Todd-Hewitt agar (Difco, BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 1.5% skim milk (38). All identified isolates were spotted and after 16 to 20 h of incubation at 37°C were examined for clearance zones surrounding the colonies (39). Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF(pCF10) was used as a positive control. Polystyrene round-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY) were used to detect in vitro biofilm formation from identified isolates. The test strains were cultivated overnight in M17 broth (Difco, BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) at 37°C. A ratio of 1:100 of the overnight culture was diluted in fresh M17 broth. Microtiter plates were incubated at 37°C without agitation for 24 h to allow for bacterial growth and biofilm formation (39). Biofilm formation was quantified using the crystal violet staining method as described by Hancock and Perego (40). All experiments included blank wells (medium without any inoculum), E. faecalis V583 (positive control for gelE and sprE expression and biofilm formation), and E. faecalis V583ΔgelE (negative control with isogenic deletion of gelE that does not form biofilm) and were replicated five times. Control strains (MMH 594, V583, OG1RF, and V583ΔgelE) were obtained from Lynn Hancock (Kansas State University). The deletion mutant V583ΔgelE strain was described by Thomas et al. (41). Control strains of E. hirae AA-1c and Aa-3B were obtained from our previous study by Ahmad et al. (42).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Selected isolates of E. hirae and E. faecalis were genotyped by means of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) performed using SmaI according to a previously published protocol (43) that was modified by replacing lysostaphin with mutanolysin (final concentration, 400 U/ml) in the bacterial digest. For accurate comparison of gel images, the H9812 strain of Salmonella enterica serotype Braenderup (ATCC BAA-664) digested with XbaI was included in 3 lanes of each gel. A position tolerance of 1% was used for band matching. Using BioNumerics 4.6 software (Applied Maths, Austin, TX), we created dendrograms using a similarity matrix of Dice coefficients and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) algorithm.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs for selected isolates of E. hirae and E. faecalis were determined by the broth dilution method using Mueller-Hinton broth, overnight incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, and a commercially available MIC plate according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gram-positive National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System plate [CMV3AGPF]; Trek Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH). MICs were interpreted as either susceptible or nonsusceptible using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (44) when available; otherwise National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS) (45) breakpoints were used. Antimicrobials included on the plate were tigecycline (TGC), tetracycline (TET), chloramphenicol (CHL), daptomycin (DAP), streptomycin (STR), tylosin tartrate (TYLT), quinupristin-dalfopristin (Q-D), linezolid (LZD), nitrofurantoin (NIT), penicillin (PEN), kanamycin (KAN), erythromycin (ERY), ciprofloxacin (CIP), vancomycin (VAN), lincomycin (LIN), and gentamicin (GEN).

Statistical analysis.

Data were tested for significant differences in distributions of observations between groups or culture isolates using chi-square and Fisher exact tests. Differences in the mean values of continuous data between groups of kittens were analyzed using Student's t tests. Analyses were conducted using commercial software (SigmaPlot 12; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA) and an assigned P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Kitten population demographics.

One hundred kittens were included in this study (Table 1). Kittens that died or were euthanized because of severe illness (group B) had a significantly lower average body weight than apparently healthy kittens (group A). Due to the untimely nature of death or euthanasia of kittens with severe illness, a significant difference in the duration of time between death and necropsy was observed between the two groups.

Table 1.

Demographic description of 100 kittens included in this studya

| Population description | Group A | Group B |

|---|---|---|

| Age (avg ± SD [range]) (wk) | 6.2 ± 3.6 (0.5–12) | 5.8 ± 2.4 (0.4–10) |

| Sex (no.) | ||

| Male | 22 | 25 |

| Female | 26 | 23 |

| Undetermined | 2 | 2 |

| Body wt (avg ± SD [range]) (g) | 529 ± 250 (122–1,013) | 360 ± 162b (132–922) |

| Time from death to necropsy (avg ± SD [range]) (h) | 2.9 ± 3.7 (0.75–20) | 8.6 ± 6.0b (1–18.75) |

Group A consisted of 50 kittens that were apparently healthy and euthanized by a local animal control facility because of overpopulation. Group B consisted of 50 kittens that died (n = 28) or were euthanized (n = 22) due to severe illness while under foster care at a local SPCA.

P is ≤0.001 (Student's t test).

Prevalence of clinical signs and light microscopic evidence of gastrointestinal pathology in healthy versus sick kittens.

The most commonly reported premortem clinical signs in group B kittens were referable to gastrointestinal illness, mainly diarrhea. Clinical signs of illness were not reported premortem for any group A kittens (Table 2). Light microscopic evidence of gastrointestinal tract pathology and/or infectious agents were identified in both groups of kittens (Table 3). Lesions observed via light microscopy in the gastrointestinal tract of kittens were largely nonspecific as to etiology and characterized in many cases as consisting of mild inflammatory infiltrates and crypt abscesses (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Table 2.

Categorization of clinical signs reported premortem for 100 kittens with or without enteroadherent Enterococcus spp. or enteroadherent E. coli infection

| Premortem clinical sign | Group A |

Group B |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of kittens | No. of kittens with enteroadherent bacteria and respective clinical signs |

No. (%) of kittens | No. of kittens with enteroadherent bacteria and respective clinical signs |

|||

| Enterococcus | E. coli | Enterococcus | E. coli | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 0 (0) | 25 (50) | 2 | 5 | ||

| Upper respiratory/ocular | 0 (0) | 20 (40) | 1 | 3 | ||

| Wounded or disabled | 0 (0) | 7 (14) | 0 | 2 | ||

| Failure to thrive | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | 2 | 0 | ||

| Unexpected death | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 1 | 0 | ||

| None recorded | 50 (100) | 9 | 0 | 2 (4) | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 50 | 9 | 0 | 50a | 7 | 9 |

Eleven kittens in group B had more than one category of clinical signs reported premortem.

Table 3.

Numbers of kittens having histopathological lesions and/or infectious agents identified by light microscopy or FISH by anatomical location

| Anatomical locationa | Group A (n = 50) |

Group Bb (n = 50) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of kittens with abnormal histopathology | Infectious agents identified by light microscopy (no. of kittens) | No. of kittens with enteroadherent bacteria confirmed by FISH |

No. (%) kittens with abnormal histopathology | Infectious agents identified by light microscopy (no. of kittens) | No. of kittens with enteroadherent bacteria confirmed by FISH |

|||

| Enterococcus | E. coli | Enterococcus | E. coli | |||||

| Stomach | 2 (4) | Helicobacter (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | Sarcina (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Duodenum | 4 (8) | 3 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 | 0 | ||

| Ileum | 3 (6) | Coccidia (2), spirochetes (2) | 7 | 0 | 13 (26) | Panleukopenia susp. (3), coccidia (2), spirochetes (1), trichomonads (1) | 6 | 6c |

| Colon | 3 (6) | Spirochetes (17), trichomonads (1), ascarid eggs (1) | 0 | 0 | 10 (20) | Spirochetes (8), trichomonads (1) | 4 | 3 |

| Total | 10/50 (20) | 21/50 (42) | 9/50 (18) | 0/50 (0) | 19/50 (38) | 13/50 (26) | 7/50 (14) | 9/50 (18) |

| Lung | 1 (2) | 7 (14) | FHV-1 susp. (1), Toxoplasma susp. (2) | NE | NE | |||

| Hepatobiliary | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | Toxoplasma susp. (1) | NE | NE | |||

| Pancreas | 0 | 1 (2) | Toxocara (1) | NE | NE | |||

| Total | 5/50 (10) | 0/50 (0) | 11/50 (22) | 4/50 (8) | ||||

Kittens may have had abnormal histopathology and/or infectious agents identified in more than one anatomical location.

susp., suspected; FHV-1, feline herpesvirus 1; NE, tissues not examined by means of FISH.

In two kittens, the small intestinal location of enteroadherent bacteria could not be ascribed to duodenum versus ileum.

Adherence of Enterococcus spp. to the small intestinal epithelium is more common and extensive in healthy versus sick kittens.

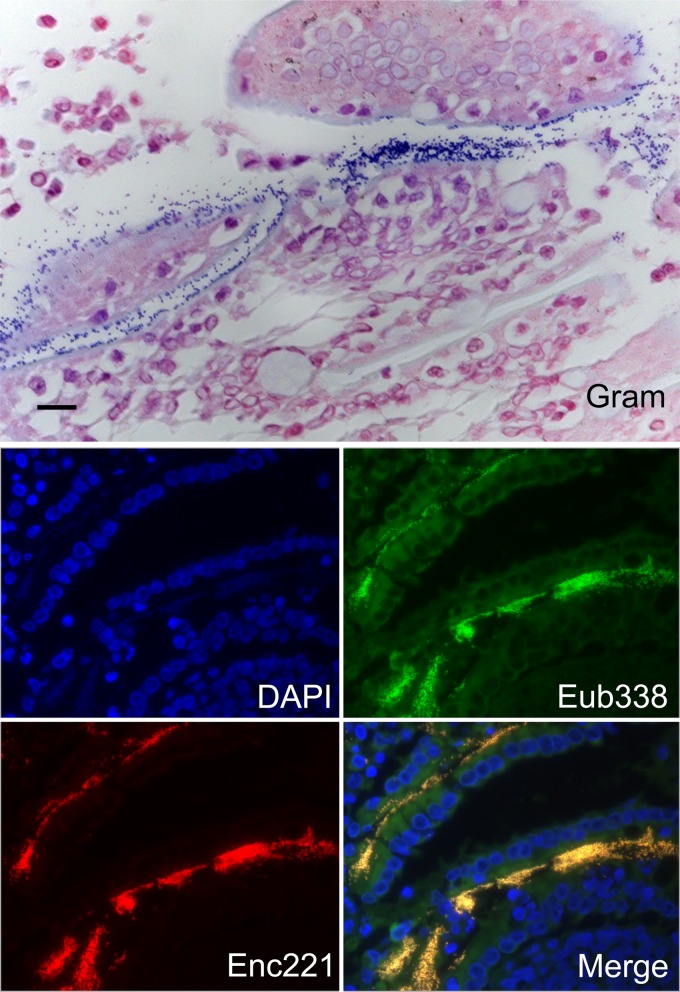

A total of 9 group A and 7 group B kittens were observed by means of light microscopy to have Gram-positive bacteria adherent to the intestinal epithelium (Table 4). In each case, the Gram-positive bacteria were identified as enterococci by means of positive hybridization to the Enterococcus-specific probe Enc221 (Fig. 1). For species identification of adherent enterococci, DNA was extracted from each paraffin-embedded intestinal specimen in which the adherent enterococci were observed. In 8/9 group A kittens, Enterococcus species-specific PCR performed on the extracted DNA identified E. hirae and not E. faecalis or E. faecium as the adherent enterococci. In contrast, E. hirae was identified as the adherent Enterococcus sp. in only 2/7 group B kittens. The remaining group B kittens were PCR negative for E. hirae, E. faecalis, and E. faecium (Table 4). Feline GAPDH gene sequences were amplified from each extracted DNA sample.

Table 4.

Kittens identified with enteroadherent bacteria and subsequent bacterium species identification

| In situ identity of enteroadherent bacteria | No. of kittens with enteroadherent bacteria/total no. tested (%)a in group: |

|

|---|---|---|

| A | B | |

| Enterococcus spp. | 9/50 (18%) | 7/50 (14%) |

| E. hirae confirmed by PCR | 8/9 (89%) | 2/7 (29%)b |

| Species undetermined by PCR | 1/9 (11%) | 5/7 (71%)b |

| Escherichia coli | 0/50 (0%) | 9/50 (18%)c |

| eae positive by PCR | 3/9 (33.3%) | |

| eae undetermined by PCR | 6/9 (66.7%) | |

Enteroadherent bacteria were detected by light microscopy and identified to the genus level by fluorescence in situ hybridization and to the species level by PCR performed on the same formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens in which enteroadherent bacteria were observed. Kittens were apparently healthy (group A; n = 50) or had died or were euthanized due to severe illness (group B; n = 50).

P is ≤0.05 (Fisher's exact test).

P is ≤0.01 (Fisher's exact test).

Fig 1.

Demonstration of enterococci adhering to the small intestinal epithelium of an apparently healthy kitten. Extensive colonies of bacteria are shown along the apical epithelium by means of Gram stain and fluorescence in situ hybridization using an oligonucleotide probe specific for eubacteria (Eub-338-FAM) or Enterococcus spp. (Enc-221-Cy3). Sections were nuclear counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Bar = 20 μm.

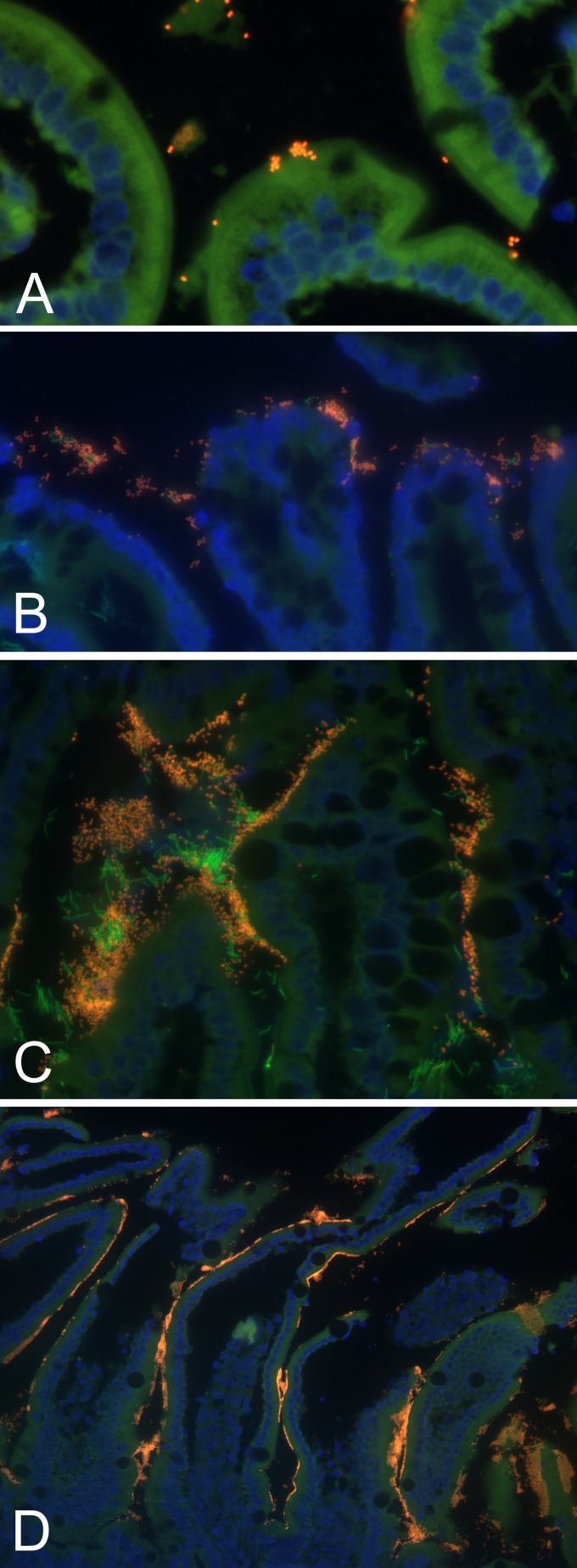

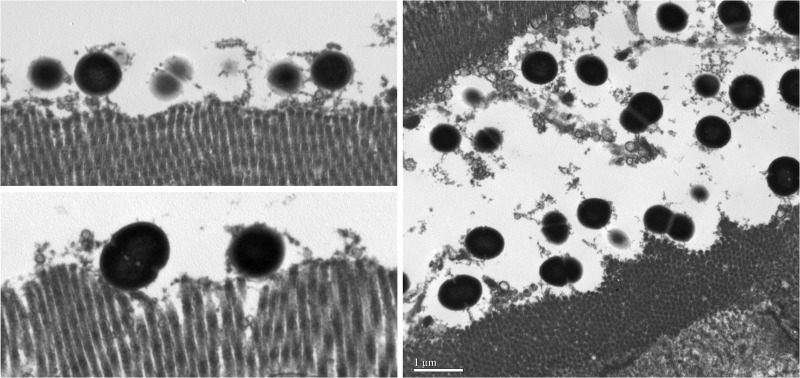

The anatomic location, number, and extent of enteroadherent enterococci present throughout the intestinal tract differed descriptively between group A and group B kittens (Table 3). In group A kittens, adherence of enterococci was restricted to the small intestine and the bacteria were more often observed in large numbers that extensively colonized the surface epithelium. In group B kittens, adherence of enterococci was also demonstrated in the colon and the bacteria were observed in scant numbers to focally colonize the epithelium (Table 5 and Fig. 2). Using two representative specimens that were identified by light microscopy as having scant versus severe adherence of enterococci, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was utilized to confirm the ultrastructural presence of direct interaction between the enterococci and the intestinal epithelial microvilli (Fig. 3). There were no associations between the presence of enteroadherent enterococci and light microscopic evidence of gastrointestinal inflammation, duration of time between death and necropsy, presence or absence of autolysis, or whether the kitten had died or was euthanized.

Table 5.

Semiquantitative description of the number and distribution of adherent enterococci in the intestinal tracts of kittens

| No. of adherent enterococcia | Group A (no.) |

Group B (no.) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kittens | Bacterial distribution |

Kittens | Bacterial distribution |

|||

| Focal | Diffuse | Focal | Diffuse | |||

| Scant | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Mild | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Severe | 3 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Total | 9 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 1 |

Adherent enterococci were identified by means of fluorescence in situ hybridization. Kittens were apparently healthy (group A; n = 9) or had died or were euthanized due to severe illness (group B; n = 7). Representative images of each description can be seen in Fig. 2.

Fig 2.

Representative results of semiquantitative scoring of the number and extent of enteroadherent enterococci in 4 healthy group A kittens. (A) Scant, focal; (B) mild, focal; (C) moderate, diffuse; (D) severe, diffuse. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed using an oligonucleotide probe specific for eubacteria (Eub-338-FAM) or Enterococcus spp. (Enc-221-Cy3). Specimens were nuclear counterstained with DAPI.

Fig 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of enterococci interacting directly with the intestinal epithelial microvilli. The micrographs in the left panel were taken of a specimen with light microscopic evidence of scant, focal adherence of enterococci. The micrograph in the right panel was taken of a specimen with light microscopic evidence of severe diffuse adherence of enterococci. These specimens share the same origins as those shown in Fig. 2A and D, respectively.

Adherence of E. coli to the small intestinal epithelium is associated with kitten mortality.

No kittens in group A and 9 kittens in group B were observed to have palisades of Gram-negative bacteria adherent to the small intestinal (n = 6) or colonic epithelium (n = 3) by means of light microscopy (Table 4). In each kitten the Gram-negative bacteria were identified as E. coli by positive hybridization to the E. coli/Shigella-specific oligonucleotide probe. In 3/9 group B kittens, eae gene sequences were amplified from DNA extracted from the corresponding paraffin-embedded tissue specimen. Notably, enteroadherent enterococci were not observed in any group B kittens diagnosed with adherent E. coli infection.

Ileum mucosa-associated enterococci are represented by E. hirae in apparently healthy kittens and E. faecalis in sick kittens.

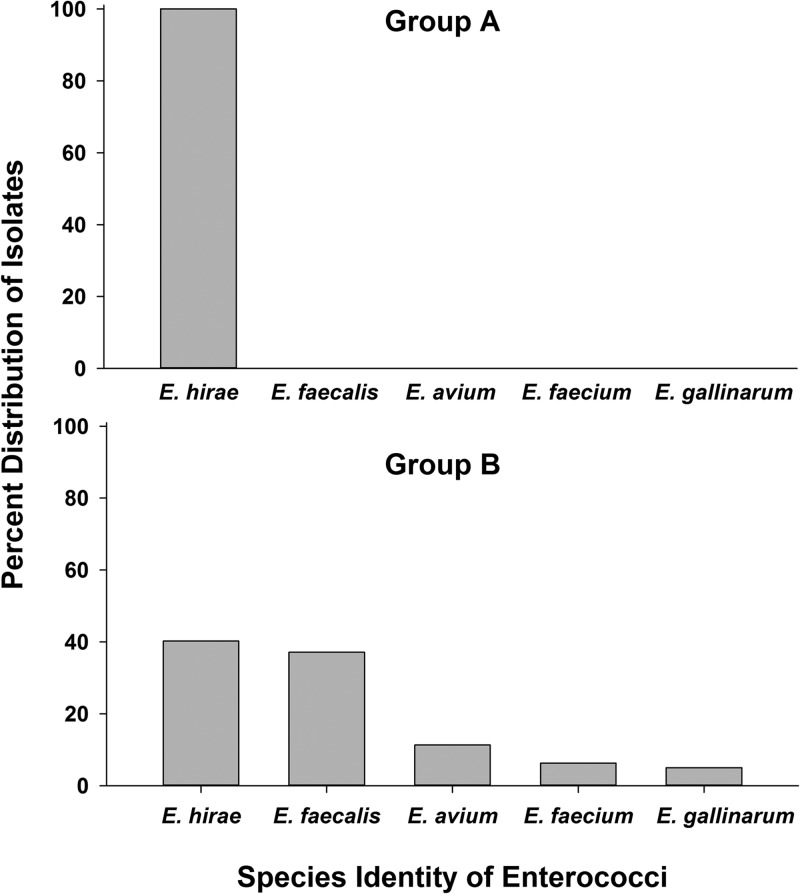

Selective culture of the ileum mucosa-associated bacteria for enterococci generated a total of 331 Enterococcus isolates from 31 group A and 24 group B kittens. Six different species of enterococci were represented. E. hirae was the most common species isolated from the kittens and was identified significantly more often in kittens from group A. In contrast, E. faecalis was isolated significantly more often from kittens in group B (Table 6). There were no significant differences in isolation of E. hirae in either group of kittens based on the duration of time between death and plating of intestinal swab samples. Sixteen kittens in group B received oral antibiotics for an unspecified duration prior to death, including amoxicillin (n = 9), cefazolin (n = 5), doxycycline (n = 2), amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 1), and azithromycin (n = 1). However, a history of antibiotic administration was not significantly associated with isolation of either E. faecalis or E. hirae. Enterococcus faecium was isolated from 3 kittens in group B, one of which had a history of receiving an E. faecium-containing probiotic (FortiFlora; Nestlé Purina, Vevey, Switzerland). The same probiotic was historically given to 6 additional group B kittens, none of which had E. faecium isolated from the ileum mucosa. An unbiased representation of the diversity of isolates obtained from individual group A and B kittens each having ≥8 isolates obtained is shown in Fig. 4.

Table 6.

Species identification of enterococci isolated from the ileum mucosa of apparently healthy kittens

| Enterococcus spp. identified | Group A (n = 153 isolates) |

Group B (n = 178 isolates) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. (%) of kittens | Total no. (%) of isolates | Total no. (%) of kittens | Total no. (%) of isolates | |

| E. hirae | 29 (58) | 148 (97) | 14 (28)c | 75 (42) |

| E. faecalis | 2 (4) | 3 (2) | 10 (20)b | 64 (36) |

| E. faecium | 1 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (6) | 12 (7) |

| E. avium | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 18 (10) |

| E. gallinarum | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 8 (4) |

| E. seriolicida | 1 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Total | 31/50 (62)a | 153/153 (100) | 24/50 (48)a | 178/178 (100) |

In several kittens, multiple species of enterococci were isolated. Enterococcal species were identified by either multiplex PCR (30) or sequencing of the sodA gene (35). The number (%) of total isolates of each species depicted is biased by variation between kittens in the number of isolates chosen for purification. An unbiased representation of the distribution of isolates between group A and B kittens is shown in Fig. 3.

P is <0.05.

P is <0.01 (Fisher's exact test).

Fig 4.

Population diversity of enterococcal species from 12 group A (n = 120 isolates) and 13 group B (n = 159 isolates) kittens, each of which had ≥8 individual isolates identified as to species. Four common species, E. faecalis, E. faecium, E. casseliflavus, and E. gallinarum, were identified using multiplex PCR (30). PCR amplification and sequencing of the sodA gene were carried out for isolates not identified by multiplex PCR (35).

Ileum mucosa-associated E. hirae lack phenotypic and genotypic determinants of enterococcal virulence.

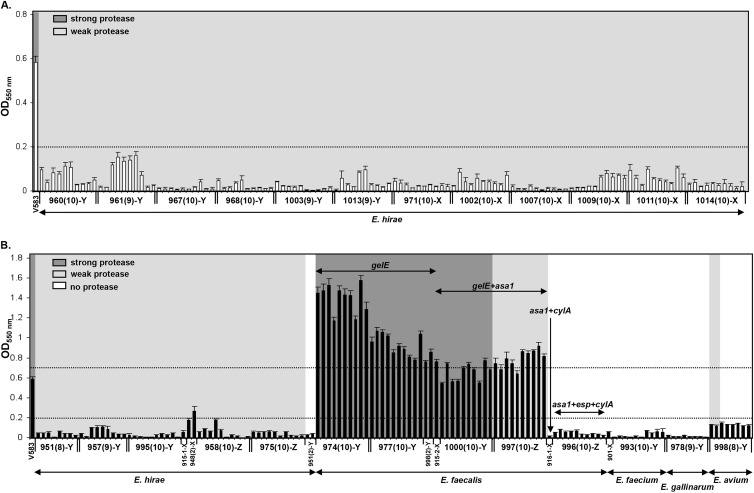

To further examine the ileum mucosa-associated isolates of E. hirae for phenotypic differences that may account for enteroadherence in vivo, isolates were selected for determination of gelatinase activity and biofilm formation in vitro. A total of 89 isolates from 6 group A and 3 group B kittens each having ≥9 E. hirae isolates showed no evidence of enteroadherent enterococcal infection in vivo. These isolates were compared to 83 isolates from 6 kittens from group A and 4 from group B for which in vivo enteroadherent enterococcal or E. coli infections were observed. Irrespective of the presence of adherent enterococci or E. coli in vivo, all tested isolates of E. hirae cultured from the ileum mucosa of group A and group B kittens displayed similar weak gelatinase activity and failure to form biofilm in vitro (Fig. 5). Putative genetic determinants of virulence (gelE, cylA, asa1, or esp) were not identified in any isolates of E. hirae (n = 172) obtained from the ileum mucosa of any group A or group B kittens.

Fig 5.

Correlations among biofilm formation, gelatinase phenotype, and presence of virulence genes (gelE, asa1, esp, and cylA) in enterococci isolated from 12 group A kittens (n = 120 isolates) (A) and 13 group B kittens (n = 133 isolates) (B). The dotted lines indicate biofilm formation activity levels (<0.2, no biofilm; 0.2 to 0.7, biofilm; >0.7, strong biofilm). Kitten numbers are presented on the x axis followed by the total numbers of characterized isolates in parentheses. Letters following the kitten numbers indicate kittens with adherent enterococci (X), no adherent bacteria (Y), or adherent E. coli (Z). E. faecalis V583 was used as a positive control. Bars correspond to the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of 5 replicate experiments. OD550, optical density at 550 nm.

Ileum mucosa-associated E. faecalis has gelatinase activity, strong biofilm formation in vitro, and carries virulence traits.

Having demonstrated that non-E. hirae enterococci were isolated almost exclusively from diseased kittens, we tested 81 non-E. hirae isolates that were cultured from the ileum mucosa of 12 group B kittens for gelatinase activity and biofilm formation in vitro. Isolates of E. faecalis (41/54) obtained from 6/8 group B kittens demonstrated strong biofilm formation and/or gelatinase activity. Additionally, all E. faecalis isolates carried one or more putative virulence traits (Fig. 5).

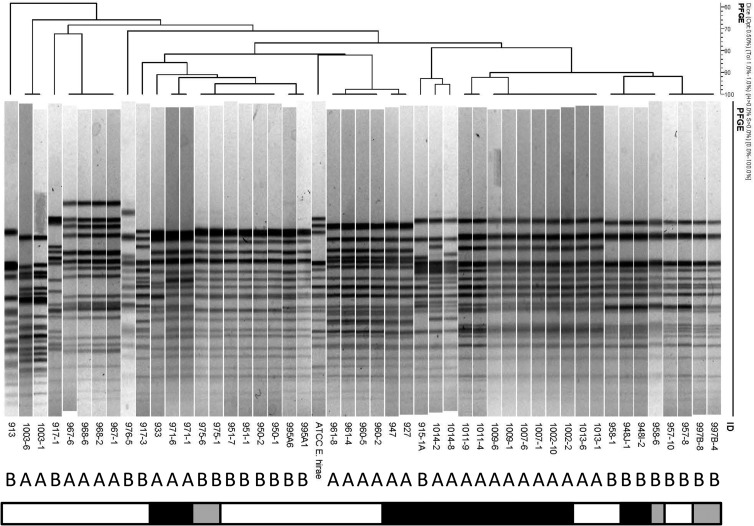

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis supports genomic similarity among E. hirae isolates cultured from the ileum mucosa of kittens with enteroadherent enterococci.

To examine the genomic similarities among ileum mucosa-associated E. hirae isolates and their relationships to health versus illness of the kittens or the presence of enteroadherent enterococci or E. coli in vivo, PFGE was performed. One (if only 1 isolate) or 2 (if ≥2) isolates were examined from each kitten that had E. hirae cultured from ileum mucosa and either enteroadherent enterococci or E. coli identified by FISH. Two isolates were examined from each kitten that had ≥10 isolates of E. hirae cultured from ileum mucosa and for which neither enteroadherent enterococci nor E. coli isolates were identified (Fig. 6). There were no distinct differences in PFGE patterns observed between isolates from group A and group B kittens. However, kittens within each group frequently shared similar genotypes of E. hirae but none of these genotypes was shared by both groups. Accordingly, the E. hirae population appeared to be genotypically distinguishable among the healthy versus sick kittens. There were no distinct differences in PFGE patterns observed between E. hirae isolates based on whether or not they were obtained from kittens that had enteroadherent enterococci observed in vivo (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of 48 E. hirae isolates cultured from the ileum mucosa of apparently healthy kittens (group A; n = 15) and kittens that died or were euthanized due to severe illness (group B; n = 12). Bar denotes light microscopic findings in the kitten from which the isolate was obtained (white, no enteroadherent enterococci or EPEC observed; black, enteroadherent enterococci present; gray, EPEC present). Numerical values indicate the identities of the kittens and isolates. The type strain is E. hirae ATCC 8043.

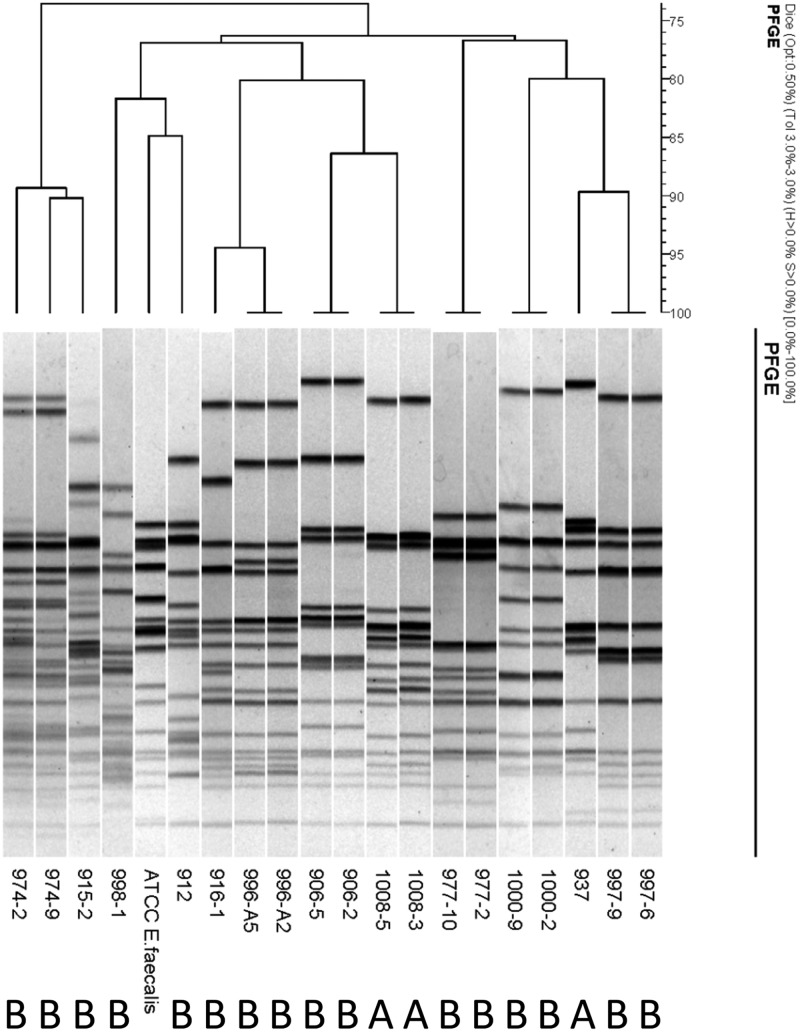

Isolates of E. faecalis from the ileum mucosa of kittens are genomically diverse.

To determine the genomic similarity among E. faecalis isolates, as predominantly obtained from kittens in group B, PFGE was performed on 1 or 2 representative isolates from each kitten (Fig. 7). No clusters could be assigned to the typed E. faecalis isolates. With the use of a similarity index cutoff value of >85%, the isolates appeared quite diverse among different kittens. However, multiple isolates from the same kitten were genotypically indistinguishable, indicating unique pulsotypes for each kitten.

Fig 7.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of 19 E. faecalis isolates cultured from the ileum mucosa of apparently healthy kittens (group A; n = 2) and kittens that died or were euthanized due to severe illness (group B; n = 10). Numerical values indicate identities of the kittens and isolates. The type strain is E. faecalis ATCC 29212.

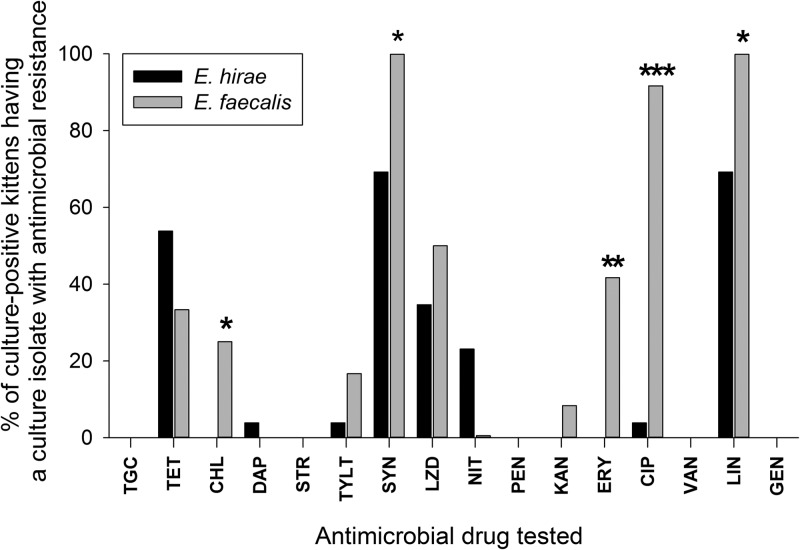

Multiple and specific antimicrobial resistance is more common among isolates of E. faecalis compared to those of E. hirae.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on isolates of E. faecalis (n = 18) and E. hirae (n = 27), selected on the basis of different PFGE profiles, from 12 and 26 kittens, respectively. Resistance to multiple (≥3) antimicrobial drugs was significantly more common among the isolates of E. faecalis (17/18) than those of E. hirae (16/27) (P = 0.014, Fisher's exact test). The prevalences of resistance to specific antimicrobial drugs among kittens harboring E. hirae or E. faecalis are shown in Fig. 8. Compared to E. hirae, E. faecalis isolates were significantly more likely to be resistant to chloramphenicol, quinupristin-dalfopristin, erythromycin, lincomycin, and ciprofloxacin (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). There were no significant relationships between multiple antimicrobial resistance and kitten group (A or B), PFGE pulsotype, or history of antibiotic administration.

Fig 8.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test results for ileal mucosa culture isolates of E. hirae (n = 27) from 15 group A and 11 group B kittens and E. faecalis (n = 18) from 2 group A and 10 group B kittens. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (Fisher's exact test). TGC, tigecycline; TET, tetracycline; CHL, chloramphenicol; DAP, daptomycin; STR, streptomycin; TYLT, tylosin tartrate; SYN, quinupristin-dalfopristin; LZD, linezolid; NIT, nitrofurantoin; PEN, penicillin; KAN, kanamycin; ERY, erythromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; VAN, vancomycin; LIN, lincomycin; GEN, gentamicin.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to characterize the enterococcal community of the distal small intestine of cats. We specifically focused on the mucosa-associated enterococci in the ileum of very young kittens. This decision was based on a strong association of small intestinal disease with mortality in this population, recognition that overall numbers of bacteria are highest in the ileum compared to other regions of the small intestine, the importance of the ileum as a portal of entry for invasive bacterial pathogens, and the likelihood of also observing concurrent adherent enterococci in this region. Moreover, bacteria that associate with the mucosal surface have a unique composition and greater influence on intestinal epithelial function than those generally residing in the lumen (46). In fact, 60% of the terminally ill kittens in this study were euthanized or died with clinical signs and/or histopathological evidence of gastrointestinal tract disease; the majority of which was attributed to the small intestine. It was not the purpose of this study to establish the cause of death in these kittens, and light microscopic examination of the intestinal tract was generally unrewarding in identifying any specific diagnoses.

In this study we identified E. hirae as the dominant species of enterococci to colonize the ileal mucosa in apparently healthy young kittens. The only prior studies to examine the microbiota of the feline small intestine focused on the lumen-dwelling bacteria and were performed in older cats. In these studies, enterococci were either not identified in the small intestine (47) or were identified as represented predominantly by E. faecalis (48–50). Enterococcus faecalis (51–54), followed by E. faecium (55) and E. hirae (11), are the most commonly reported species of enterococci to dominate the fecal flora of cats, where the numbers of enterococci can average 106 CFU per gram of feces (11).

In kittens that died or were euthanized due to severe illness, there was a major difference in the species of enterococci associated with the ileum mucosa. Significantly greater numbers of these kittens were colonized by E. faecalis, suggesting that the ileum mucosa-associated microbiota in sick kittens reflects a more adult fecal-like composition (51–54) of enterococci. Moreover, the E. faecalis isolates obtained from these kittens were characterized as carrying multiple genotypic and phenotypic attributes of virulence. This is in contrast to E. faecalis isolates from healthy cats, in which the carriage of virulence genes appears to be uncommon (56), albeit there are a few reports of examinations of genotypic virulence of E. faecalis in healthy cats (11, 57). Most notable among the virulence traits of E. faecalis from sick kittens was a high prevalence of gelE, a gene encoding the zinc metalloproteinase gelatinase, and concurrent documentation of gelatinase activity. Gelatinase is implicated in enhancing enterococcal virulence by conferring an ability to form solid-surface environmental biofilms (40), and in the present study E. faecalis gelatinase activity was associated with strong biofilm formation on polystyrene. There was additionally a high prevalence of asa1, a gene encoding aggregation substance, among E. faecalis isolates from sick kittens. Aggregation substance is a surface bacterial adhesin that has been demonstrated to increase attachment of E. faecalis to intestinal epithelial cells in vitro (58). Whether gelE or asa1 conferred to E. faecalis an ability to outcompete E. hirae for representation within the ileum mucosa-associated microbiota in these sick kittens is unknown.

In addition to carrying multiple genetic virulence factors, E. faecalis isolates were frequently resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin, lincomycin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, chloramphenicol, linezolid, and ciprofloxacin. None of the E. faecalis isolates demonstrated resistance to penicillin, aminoglycosides, or vancomycin. Intrinsic or acquired resistance to quinupristin-dalfopristin, tetracyclines, and macrolides is commonly reported among feline isolates of E. faecalis (11, 52–54). In contrast, resistance to newer-generation antimicrobial drugs (linezolid) or those commonly reserved for treatment of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in cats (ciprofloxacin) was somewhat surprising (11, 52). None of the kittens had a history of treatment with fluoroquinolones. Compared to isolates of E. faecalis, isolates of E. hirae obtained from apparently healthy or sick kittens were significantly less often resistant to multiple (≥3) antimicrobial drugs. Less frequent antimicrobial resistance among E. hirae than E. faecalis and E. faecium of fecal origin in cats has been previously documented (11).

Whether or not the virulent, antimicrobial-resistant isolates of E. faecalis colonizing the ileum mucosa of sick kittens in this study originated from commensal E. faecalis or were acquired from the environment is not known. Based on the PFGE genotypes of representative E. faecalis isolates from each kitten, multidrug-resistant strains did not share colonization of the ileum mucosa with other strains. Sick kittens possibly had a greater susceptibility and opportunity for colonization by resistant strains of E. faecalis, as they spent time in a foster care or hospital environment in contrast to the apparently healthy kittens that were frequently euthanized shortly after their receipt to the animal control facility. An opportunistic infection of the sick kittens by virulent E. faecalis is supported by studies demonstrating frequent antibiotic resistance in fecal enterococci in cats from catteries, hospitalized cats, and resident cats in veterinary clinics (11, 53, 54). However, whether the colonization of ileum mucosa-associated microbiota by E. faecalis was a contributing cause or consequence of gastrointestinal disease and terminal illness in the sick kittens reported here is unknown. What appears more certain is that the intestinal enterococci of sick kittens may serve as a reservoir for potential transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes to the environment and/or to other hosts.

Apart from being identified as the dominant cultivable species of enterococci in the ileum mucosa-associated microbiota in apparently healthy young kittens, overt and extensive adhesion of E. hirae to the small intestinal epithelium was observed in 16% of the kittens in this population. Given that detection of this event requires light microscopy and only two biopsy specimens of the small intestine from each kitten were examined, it is likely that the prevalence of this phenomenon was grossly underestimated. While adherent enterococci were also detected in the sick kittens, considerably fewer bacteria were observed and they were infrequently identified to the species level by means of PCR. We attribute our inability to identify the adherent enterococci in sick kittens as due to the presence of fewer bacteria (and less enterococcal DNA) and as less likely due to adhesion by non-E. hirae enterococci. Our finding that enteroadherent E. hirae is common and extensive in apparently healthy kittens provides a contrast to the numerous uncontrolled case reports describing enteroadherent enterococci in association with diarrhea in young animals (17–25). Although the identity and virulence attributes of the enteroadherent enterococci in most of these reports was not determined, it should be considered that the adherent enterococci may not have been the primary cause of diarrhea in these animals.

The mechanism(s) by which E. hirae adhere to the intestinal epithelium in these young kittens is not clear. Based on a comparative lack of virulence among the E. hirae isolates tested from the kittens, it is evident that the genotypic (gelE and asa1) and phenotypic (gelatinase activity) attributes generally regarded as essential for biofilm formation in vitro are not required for enteroadhesion in vivo. PFGE revealed that the E. hirae population is genotypically very diverse and clustering did not correlate with enteroadherence in vivo. A notable feature of enteroadherent E. hirae is a light microscopic appearance indistinguishable from that of EPEC that requires a Gram stain for their differentiation (25). It is likewise intriguing that adherence of E. coli was documented commonly and exclusively in sick kittens in this study but was not observed in any sick kitten with enteroadherent enterococci. This not only identifies enteroadherent E. coli as a potentially important intestinal pathogen in young kittens but also suggests that enteroadherence of E. hirae might competitively inhibit or otherwise deter the attachment of E. coli.

Results of this study identify E. hirae as the most common mucosa-associated species of enterococci to inhabit the small intestine in apparently healthy young kittens. Furthermore, adherence of E. hirae to the small intestinal epithelium was common and extensive in this population. Isolates of E. hirae generally lacked phenotypic and genotypic determinants of virulence. In contrast, kittens that died or were euthanized due to severe illness were significantly more often identified as colonized by E. faecalis. This population of E. faecalis was characterized by a high level of gelatinase activity, strong biofilm formation on polystyrene, the presence of virulence determinants, and multiple antimicrobial resistances. Moreover, attachment of E. coli to the intestinal epithelium was exclusively and significantly associated with terminal illness and was not documented in any kitten for which enteroadherent E. hirae was observed. These findings identify a significant difference in the species of enterococci colonizing the ileum mucosa of healthy versus terminally ill young kittens and suggest that E. hirae represents an important commensal in this population. Given the significance of small intestinal disease as a cause of mortality in young kittens, these findings have important implications toward identifying species of enterococci for their potential to significantly impact the survival of very young kittens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants W09-022 and W11-013 from the Winn Feline Foundation.

We thank Maria Stone, Megan Fauls, Mondy Lamb, Lisa Kroll, Ashley Williams, Hannah Preedy, Allison Baker, Wendy Savage, and Klara Zurek for valuable technical assistance. Transmission electron microscopy was performed in the Laboratory for Advance Electron and Light Optical Methods in the College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 August 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00481-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Veterinary Medical Association 2012. Overview: total pet ownership and pet population, p 31–32 In U.S. pet ownership and demographics sourcebook, section 1. American Veterinary Medical Association, Schaumburg, IL [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott FW, Geissinger C. 1978. Kitten mortality survey. Fel. Pract. 8:31–34 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutter FB, Levine JF, Stoskopf MK. 2004. Reproductive capacity of free-roaming domestic cats and kitten survival rate. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 225:1399–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young C. 1973. Preweaning mortality in specific pathogen-free kittens. J. Small Anim. Pract. 14:391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparkes AH, Rogers K, Henley WE, Gunn-Moore DA, May JM, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Bessant C. 2006. A questionnaire-based study of gestation, parturition and neonatal mortality in pedigree breeding cats in the UK. J. Fel. Med. Surg. 8:145–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Root MV, Johnston SD, Olson PN. 1995. Estrous length, pregnancy rate, gestation and parturition lengths, litter size, and juvenile mortality in the domestic cat. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 31:429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray JK, Skillings E, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. 2008. A study of risk factors for cat mortality in adoption centres of a UK cat charity. J. Feline Med. Surg. 10:338–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cave TA, Thompson H, Reid SW, Hodgson DR, Addie DD. 2002. Kitten mortality in the United Kingdom: a retrospective analysis of 274 histopathological examinations (1986 to 2000). Vet. Rec. 151:497–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bybee SN, Scorza AV, Lappin MR. 2011. Effect of the probiotic Enterococcus faecium SF68 on presence of diarrhea in cats and dogs housed in an animal shelter. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 25:856–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart ML, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM, Webb CB. 2012. Open-label trial of a multi-strain synbiotic in cats with chronic diarrhea. J. Feline Med. Surg. 14:240–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh A, Kukanich K, Brown CE, Zurek L. 2012. Resident cats in small animal veterinary hospitals carry multi-drug resistant enterococci and are likely involved in cross-contamination of the hospital environment. Front. Microbiol. 3:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner KA, Hartmann FA, Trepanier LA. 2007. Bacterial culture results from liver, gallbladder, or bile in 248 dogs and cats evaluated for hepatobiliary disease: 1998–2003. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 21:417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litster A, Moss S, Platell J, Trott DJ. 2009. Occult bacterial lower urinary tract infections in cats—urinalysis and culture findings. Vet. Microbiol. 136:130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costello MF, Drobatz KJ, Aronson LR, King LG. 2004. Underlying cause, pathophysiologic abnormalities, and response to treatment in cats with septic peritonitis: 51 cases (1990–2001). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 225:897–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KuKanich KS, Ghosh A, Skarbek JV, Lothamer KM, Zurek L. 2012. Surveillance of bacterial contamination in small animal veterinary hospitals with special focus on antimicrobial resistance and virulence traits of enterococci. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 240:437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton E, Kaneene JB, May KJ, Kruger JM, Schall W, Beal MW, Hauptman JG, DeCamp CE. 2012. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Enterococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. isolated from surfaces in a veterinary teaching hospital. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 240:1463–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etheridge ME, Vonderfecht SL. 1992. Diarrhea caused by a slow-growing Enterococcus-like agent in neonatal rats. Lab. Anim. Sci. 42:548–550 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etheridge ME, Yolken RH, Vonderfecht SL. 1988. Enterococcus hirae implicated as a cause of diarrhea in suckling rats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1741–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheon DS, Chae C. 1996. Outbreak of diarrhea associated with Enterococcus durans in piglets. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 8:123–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vancanneyt M, Snauwaert C, Cleenwerck I, Baele M, Descheemaeker P, Goossens H, Pot B, Vandamme P, Swings J, Haesebrouck F, Devriese LA. 2001. Enterococcus villorum sp. nov., an enteroadherent bacterium associated with diarrhoea in piglets. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers DG, Zeman DH, Erickson ED. 1992. Diarrhea associated with Enterococcus durans in calves. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 4:471–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzipori S, Hayes J, Sims L, Withers M. 1984. Streptococcus durans: an unexpected enteropathogen of foals. J. Infect. Dis. 150:589–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins JE, Bergeland ME, Lindeman CJ, Duimstra JR. 1988. Enterococcus (Streptococcus) durans adherence in the small intestine of a diarrheic pup. Vet. Pathol. 25:396–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapointe JM, Higgins R, Barrette N, Milette S. 2000. Enterococcus hirae enteropathy with ascending cholangitis and pancreatitis in a kitten. Vet. Pathol. 37:282–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicklas JL, Moisan P, Stone MR, Gookin JL. 2010. In situ molecular diagnosis and histopathological characterization of enteroadherent Enterococcus hirae infection in pre-weaning-age kittens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:2814–2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janeczko S, Atwater D, Bogel E, Greiter-Wilke A, Gerold A, Baumgart M, Bender H, McDonough PL, McDonough SP, Goldstein RE, Simpson KW. 2008. The relationship of mucosal bacteria to duodenal histopathology, cytokine mRNA, and clinical disease activity in cats with inflammatory bowel disease. Vet. Microbiol. 128:178–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wellinghausen N, Bartel M, Essig A, Poppert S. 2007. Rapid identification of clinically relevant Enterococcus species by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3424–3426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray SG, Hunter SA, Stone MR, Gookin JL. Assessment of reproductive tract disease in cats at risk for Tritrichomonas foetus infection. Am. J. Vet. Res. 71:76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arias CA, Robredo B, Singh KV, Torres C, Panesso D, Murray BE. 2006. Rapid identification of Enterococcus hirae and Enterococcus durans by PCR and detection of a homologue of the E. hirae mur-2 gene in E. durans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1567–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kariyama R, Mitsuhata R, Chow JW, Clewell DB, Kumon H. 2000. Simple and reliable multiplex PCR assay for surveillance isolates of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3092–3095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. 1995. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:24–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng S, McCleskey FK, Gress MJ, Petroziello JM, Liu R, Namdari H, Beninga K, Salmen A, DelVecchio VG. 1997. A PCR assay for identification of Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1248–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franck SM, Bosworth BT, Moon HW. 1998. Multiplex PCR for enterotoxigenic, attaching and effacing, and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from calves. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1795–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macovei L, Zurek L. 2007. Influx of enterococci and associated antibiotic resistance and virulence genes from ready-to-eat food to the human digestive tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6740–6747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poyart C, Quesnes G, Trieu-Cuot P. 2000. Sequencing the gene encoding manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase for rapid species identification of enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:415–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vankerckhoven V, Van Autgaerden T, Vael C, Lammens C, Chapelle S, Rossi R, Jabes D, Goossens H. 2004. Development of a multiplex PCR for the detection of asa1, gelE, cylA, esp, and hyl genes in enterococci and survey for virulence determinants among European hospital isolates of Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4473–4479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro TC, Pinto V, Gasper F, Lopes MFS. 2008. Enterococcus hirae causing wound infections in a hospital. J. Chin. Clin. Med. 3:150–152 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilmore MS, Coburn PS, Nallapareddy R, Murray BE. 2002. Enterococcal virulence, p 301–354 In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Courvalin P, Dunny GM, Murray BE, Rice LB. (ed), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology and antibiotic resistance. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macovei L, Ghosh A, Thomas VC, Hancock LE, Mahmood S, Zurek L. 2009. Enterococcus faecalis with the gelatinase phenotype regulated by the fsr operon and with biofilm-forming capacity are common in the agricultural environment. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1540–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hancock LE, Perego M. 2004. The Enterococcus faecalis fsr two-component system controls biofilm development through production of gelatinase. J. Bacteriol. 186:5629–5639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas VC, Thurlow LR, Boyle D, Hancock LE. 2008. Regulation of autolysis-dependent extracellular DNA release by Enterococcus faecalis extracellular proteases influences biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 190:5690–5698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmad A, Ghosh A, Schal C, Zurek L. 2011. Insects in confined swine operations carry a large antibiotic resistant and potentially virulent enterococcal community. BMC Microbiol. 11:23. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luey CK, Chu YW, Cheung TK, Law CC, Chu MY, Cheung DT, Kam KM. 2007. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for subtyping of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. J. Microbiol. Methods 68:648–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 20th informational supplement. CLSI M100-S20. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Department of Agriculture ARS 2012. 2010 NARMS animal arm annual report. Food and Drug Administration/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/U.S. Department of Agriculture, Athens, GA: http://ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/66120508/NARMS/NARMS2010/NARMS%20USDA%202010%20Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA. 2005. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308:1635–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritchie LE, Steiner JM, Suchodolski JS. 2008. Assessment of microbial diversity along the feline intestinal tract using 16S rRNA gene analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:590–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osbaldiston GW, Stowe EC. 1971. Microflora of alimentary tract of cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 32:1399–1405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sparkes AH, Papasouliotis K, Sunvold G, Werrett G, Clarke C, Jones M, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Reinhart G. 1998. Bacterial flora in the duodenum of healthy cats, and effect of dietary supplementation with fructo-oligosaccharides. Am. J. Vet. Res. 59:431–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papasouliotis K, Sparkes AH, Werrett G, Egan K, Gruffydd-Jones EA, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. 1998. Assessment of the bacterial flora of the proximal part of the small intestine in healthy cats, and the effect of sample collection method. Am. J. Vet. Res. 59:48–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Devriese LA, Cruz Colque JI, De Herdt P, Haesebrouck F. 1992. Identification and composition of the tonsillar and anal enterococcal and streptococcal flora of dogs and cats. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 73:421–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackson CR, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Davis JA, Barrett JB, Frye JG. 2009. Prevalence, species distribution and antimicrobial resistance of enterococci isolated from dogs and cats in the United States. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107:1269–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moyaert H, De Graef EM, Haesebrouck F, Decostere A. 2006. Acquired antimicrobial resistance in the intestinal microbiota of diverse cat populations. Res. Vet. Sci. 81:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leener ED, Decostere A, De Graef EM, Moyaert H, Haesebrouck F. 2005. Presence and mechanism of antimicrobial resistance among enterococci from cats and dogs. Microb. Drug Resist. 11:395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodrigues J, Poeta P, Martins A, Costa D. 2002. The importance of pets as reservoirs of resistant Enterococcus strains, with special reference to vancomycin. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 49:278–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gulhan T, Aksakal A, Ekin IH, Savasan S, Boynukara B. 2006. Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis strains isolated from humans and pets. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 30:477–482 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harada T, Tsuji N, Otsuki K, Murase T. 2005. Detection of the esp gene in high-level gentamicin resistant Enterococcus faecalis strains from pet animals in Japan. Vet. Microbiol. 106:139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sartingen S, Rozdzinski E, Muscholl-Silberhorn A, Marre R. 2000. Aggregation substance increases adherence and internalization, but not translocation, of Enterococcus faecalis through different intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Infect. Immun. 68:6044–6047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.