Abstract

Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an increasing problem worldwide but is not well documented in the United States. We report a cluster of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae cases among a mother and two daughters.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1 was an 8-year-old female with antecedent history of asthma who developed fatigue and fever of up to 104.3°F on 18 November 2012. On day 2, she consulted with her primary care physician (PCP); her chest examination was normal, and a nasopharyngeal (NP) specimen collected for influenza was negative. Her PCP recommended symptomatic treatment of the fever and a follow-up visit if there was no improvement in 3 to 4 days; no antibiotics were prescribed at this visit. By day 3 she started having additional symptoms such as cough, headache, nausea, and chest pain. She was reevaluated by her PCP on day 4; chest radiography showed an infiltrate in the right upper lobe with mild volume loss, and a 5-day course of azithromycin was subsequently prescribed. By day 6, fever persisted despite 3 days of azithromycin treatment; a repeat chest radiograph showed slight improvement in the infiltrate. Azithromycin treatment was continued, and albuterol was administered via nebulizer three times daily. Despite completion of the course of azithromycin, fever persisted, prompting the administration of cefdinir on day 8 and of corticosteroids (oral and inhaled) because of wheezing on day 9. The 10-day course of cefdinir was completed; she remained afebrile and gradually improved after 2 weeks. The total illness course was 24 days.

Patient 2.

Patient 2 was a healthy 38-year-old female (mother of patient 1) with no history of smoking or asthma. She developed fever of up to 103°F on 15 December 2012, approximately 1 month after onset of fever in patient 1. On day 2, she presented to her PCP with cough, dizziness, aches, and upper respiratory symptoms. An NP specimen collected at this visit for rapid influenza testing was negative. Given the marginal sensitivity of the rapid influenza test and widespread influenza A H3N2 virus activity in the country at the time, her PCP elected to treat an influenza-like illness with oseltamivir. The fever persisted, and azithromycin was added to the treatment regimen on day 3. She was reevaluated by her PCP on day 5, and a chest radiograph showed left lower lobe pneumonia. Based on the radiographic findings, azithromycin was stopped and levofloxacin was administered on day 5. Because of wheezing, inhaled albuterol was administered. Although the fever resolved by day 7, cough and wheezing persisted, which prompted the administration of a course of oral corticosteroids by her PCP on day 10. Cough and wheezing gradually improved over the following week, resulting in a total illness course of 17 days.

Patient 3.

Patient 3 was an otherwise healthy 10-year-old female (sister of patient 1 and daughter of patient 2) with no history of asthma. She presented with fever of up to 104.5°F, dizziness, and headache on 27 December 2012, approximately 2 weeks after the onset of fever in patient 2 and 5 weeks after the onset in patient 1. She had a temperature of 98.8°F in the office on day 2, and rhonchi were heard in the left anterior chest upon auscultation. Because of persistent headache, dizziness, and cough, she was reevaluated in the PCP's office on day 5. Auscultation revealed inspiratory rales in the left anterior chest, and chest radiography showed lingular pneumonia. Her PCP prescribed a 7-day oral course of cefdinir due to the recent history of pneumonia in the family that did not respond to azithromycin. Blood specimens were obtained for complete blood count (CBC), culture, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) analyses, and two NP specimens were collected for viral and Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR. The laboratory results came back on day 9 and were as follows: CBC was normal; ESR was elevated (23 mm/h [normal range, 0 to 20]); blood culture was negative; a respiratory viral PCR panel (Quest Diagnostics) was negative; and M. pneumoniae DNA qualitative real-time PCR (Quest Diagnostics) was positive. Because of the positive PCR result for M. pneumoniae, she was started on doxycycline treatment. She improved with no further fever, but doxycycline was discontinued on day 11 because of vomiting. The total illness course was 11 days.

NP specimens (n = 2) collected from patient 3 were transferred from the Quest Diagnostics laboratory to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA) for confirmatory testing for M. pneumoniae by qPCR and culture and for determination of macrolide susceptibility. Isolation was performed using SP4 medium (Remel) as previously described (1). Total nucleic acid was extracted from NP specimens and liquid culture medium using a MagNA Pure Compact instrument with total nucleic acid isolation kit I (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. M. pneumoniae-specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as previously described (2). Both NP specimens were positive for M. pneumoniae; the threshold cycle (CT) values were approximately 15 for both specimen extracts (data not shown), indicating a relatively large amount of M. pneumoniae nucleic acid present in each specimen. An isolate was obtained from each specimen.

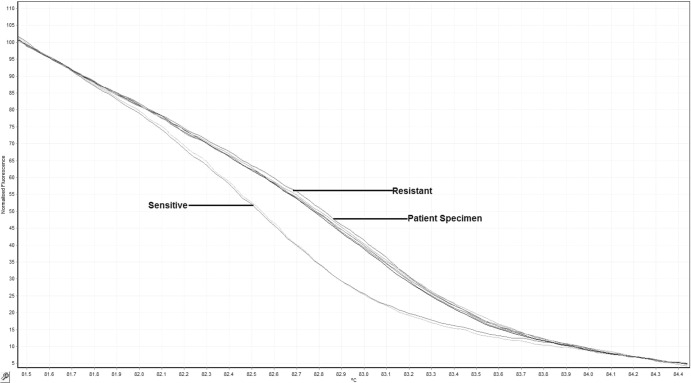

Both NP specimens and the corresponding isolates were tested for macrolide resistance using a qPCR assay with Light Upon Extension (LUX) chemistry and high-resolution melt (HRM) analysis to identify single-base mutations in the 23S rRNA gene that confer resistance to macrolide antibiotics (3). Melt patterns consistent with macrolide resistance were observed for both specimens and isolates (Fig. 1). DNA sequencing of the amplicon was performed as previously described (3); sequencing analysis revealed the presence of the A2063G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene, a single-base mutation previously shown to confer macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae (3) (Table 1).

Fig 1.

High-resolution melt (HRM) profiles of M. pneumoniae present in nasopharyngeal specimen collected from patient 3 and in macrolide-resistant and susceptible reference strains. The presence of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae is evident from the distinct melting profile. Specimens from patient 3 displayed HRM profiles consistent with that of the macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae reference strain.

Table 1.

Clinical findings for the three patients

| Characteristic | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 8 | 38 | 10 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female |

| Relationship | Younger daughter | Mother | Older daughter |

| Antecedent medical history | Asthma | None | None |

| Date of fever onset | 18 November 2012 | 15 December 2012 | 27 December 2012 |

| First antibiotic administered | Azithromycin | Azithromycin | Cefdinir |

| Second antibiotic administered | Cefdinir | Levofloxacin | Doxycycline |

| Steroids administered | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tmax (°F) | 104.3 | 103 | 104.5 |

| No. of days of fever prior to antibiotic administration | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| No. of days of fever after initial antibiotic administration | 5 | 4 | 11 |

| Total illness course (no. of days) | 24 | 17 | 11 |

| Chest X-ray result | Dense infiltrate in right upper lobe | Lower left lobe infiltrate | Lingular infiltrate |

Primary specimens and isolates were characterized by multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) using previously described methods (4, 5). Both primary specimens and isolates displayed virtually identical MLVA types (5/4/5/7/2), although variation at the Mpn1 locus was identified in one of the primary specimens and the corresponding isolate, a phenomenon that has been reported previously (4). This specimen and isolate displayed two distinct fragment sizes corresponding to two and five repeats at this VNTR locus (Table 2). Molecular typing of the gene encoding the P1 major adhesion protein using qPCR with high-resolution melt analysis identified both isolates as type 1 (Table 2) (6).

Table 2.

Laboratory results for M. pneumoniae isolates recovered from NP specimens collected from patient 3

| Patient 3 isolatea | 23S rRNA mutationb | MLVA typec | P1 type |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | A2063G | 5/4/5/7/2 | 1 |

| B | A2063G | 5/4/5/7/2 (n = 2) | 1 |

One isolate was recovered from each NP specimen (n = 2) collected from patient 3 on the same day.

Both specimens and isolates were identified as macrolide resistant by HRM analysis.

Identical MLVA types were identified in the primary specimen extract.

M. pneumoniae is a major cause of community-acquired pneumonia among children and adults. Since 2000, reports of the incidence of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae isolates have increased worldwide, perhaps due in part to the expanded use of improved diagnostic methods (7). Macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae has been implicated in individual cases, family clusters, and outbreaks in various settings in the United States and other countries (8–12). The prevalence of resistance among isolates from case series and surveillance studies in the literature ranges from 8% to 27% (13–15). We describe a household cluster of presumed macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infections diagnosed 45 days after the onset of symptoms in the index case, including laboratory confirmation in the third case. This household cluster was identified by an astute clinician who suspected macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infection because of prolonged symptoms despite multiple courses of antibiotics. Clinically, infections caused by macrolide-resistant strains of M. pneumoniae are characterized by a prolonged duration of fever, variable symptoms, and persistent cough, as demonstrated in this case report series and in other reports (16–18). In uncomplicated infections, the acute febrile period lasts about a week, while the cough and lassitude may last 2 weeks or even longer. The duration of symptoms and signs is generally shorter if antibiotics are started early in the course of illness (19). Suzuki et al. demonstrated that patients with macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infections had a median of 8 febrile days (range, 4 to 19 days) whereas patients with macrolide-susceptible M. pneumoniae infections had a median of 5 febrile days (range, 2 to 9 days) (20). Sheng et al. found that patients with macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infections had a significantly longer mean febrile duration of 3.2 days after azithromycin administration compared with 1.6 days among patients with macrolide-susceptible M. pneumoniae infections (21); this longer fever duration is similar to the fever profile of patients described in this cluster.

The clinical courses of the three patients were similar; all patients had radiological evidence of pneumonia, multiple medical consultations, and multiple courses of antimicrobials. Two of the patients described in this cluster received macrolide treatment with no clinical improvement. The last patient (for whom the diagnosis was laboratory confirmed) did not receive macrolide treatment but was given cefdinir, to which she did not respond. Clinical improvement was noted after the administration of doxycycline. The prolonged duration of symptoms and nonresponse to macrolide therapy suggest that the level of macrolide resistance conferred by the genetic mutation detected here was clinically significant and resulted in treatment failure in these otherwise healthy patients.

Macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae is caused by specific point mutations within the single-copy 23S rRNA gene which inhibit the interaction of macrolides with the large ribosomal subunit, thereby allowing protein synthesis to proceed (22). Sequencing analysis of specimens obtained from patient 3 demonstrated the presence of the A2063G transition in the 23S rRNA gene, a mutation commonly associated with macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae (23, 24). The high burden of M. pneumoniae in patient 3, as indicated by the low CT values in the detection assay, allowed the clear identification of macrolide resistance directly from the primary specimen extract without the need for an isolate.

Assays for the characterization and typing of M. pneumoniae, including P1 typing and MLVA, were utilized in this investigation. These assays can help to elucidate the relatedness of strains in outbreaks or clusters such as the one reported here. Unfortunately, specimens were available from only one of the three related cases in this report, precluding any comparison of M. pneumoniae data among family members. However, the close family contact, similarity of symptoms, and time courses of the three cases, with onset of the second and third cases occurring within the known incubation period of M. pneumoniae after onset of the first case, suggest that all three illnesses were caused by the same strain.

Macrolides such as erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin are used as first-choice therapeutic agents for treating M. pneumoniae infections. This is especially important for children, as other classes of antibiotics with activity against M. pneumoniae are not indicated or may cause adverse events in young patients (25). The advantages of clarithromycin and azithromycin over erythromycin include improved oral bioavailability, longer half-life (allowing once- or twice-daily administration), higher tissue concentrations, enhanced antimicrobial activity, and reduced gastrointestinal adverse effects (25). Recent studies have demonstrated that tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are effective treatments for patients with macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infections (26). In particular, administration of minocycline was shown to decrease the number of DNA copies found in the nasopharynxes of children with macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infections (27).

This familial cluster of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae infections highlights the need for increased awareness among clinicians of circulating macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae strains. Clinicians considering M. pneumoniae as part of a differential diagnosis should consider macrolide resistance if there is no clinical improvement after the initiation of first-choice antibiotics. Earlier detection of M. pneumoniae and its resistance profile would likely reduce the inappropriate or unnecessary use of antibiotics, the duration and severity of illness, and the spread of infection in the community. Early detection and proper treatment of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae pneumonia could also be important for prevention of outbreaks in congregate settings. Reliable diagnostic tests for rapid identification of both macrolide-sensitive and macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae strains as well as public health programs to monitor disease are needed to understand the true burden of infections due to this pathogen and to monitor trends in antibiotic resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was supported in part by an appointment to the Applied Epidemiology Fellowship Program administered by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and funded by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cooperative Agreement 5U38HM000414-5.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

There was no prior presentation of the data presented here.

The findings and conclusions in this report are ours and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Tully JG, Rose DL, Whitcomb RF, Wenzel RP. 1979. Enhanced isolation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat washings with a newly-modified culture medium. J. Infect. Dis. 139:478–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurman KA, Warner AK, Cowart KC, Benitez AJ, Winchell JM. 2011. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella spp. in clinical specimens using a single-tube multiplex real-time PCR assay. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolff BJ, Thacker WL, Schwartz SB, Winchell JM. 2008. Detection of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae by real-time PCR and high-resolution melt analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3542–3549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benitez AJ, Diaz MH, Wolff BJ, Pimentel G, Njenga MK, Estevez A, Winchell JM. 2012. Multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates from 1962 to the present: a retrospective study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3620–3626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dégrange S, Cazanave C, Charron A, Renaudin H, Bébéar C, Bébéar CM. 2009. Development of multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis for molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:914–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz SB, Thurman KA, Mitchell SL, Wolff BJ, Winchell JM. 2009. Genotyping of Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates using real-time PCR and high-resolution melt analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:756–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Atkinson TP, Hagood J, Makris C, Duffy LB, Waites KB. 2009. Emerging macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: detection and characterization of resistant isolates. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28:693–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamizono S, Ohya H, Higuchi S, Okazaki N, Narita M. 2010. Three familial cases of drug-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Eur. J. Pediatr. 169:721–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki Y, Itagaki T, Seto J, Kaneko A, Abiko C, Mizuta K, Matsuzaki Y. 30 October 2012. Community outbreak of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Yamagata, Japan in 2009. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827aa7bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Qiu S, Yang G, Song L, Su W, Xu Y, Jia L, Wang L, Hao R, Zhang C, Liu J, Fu X, He J, Zhang J, Li Z, Song H. 2012. An outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae caused by a macrolide-resistant isolate in a nursery school in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3748–3752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereyre S, Renaudin H, Charron A, Bebear C. 2012. Clonal spread of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in primary school, Bordeaux, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:343–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyashita N, Kawai Y, Akaike H, Teranishi H, Ouchi K, Okimoto N. 27 April 2013. Transmission of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae within a family. J. Infect. Chemother. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1007/s10156-013-0604-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Averbuch D, Hidalgo-Grass C, Moses AE, Engelhard D, Nir-Paz R. 2011. Macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Israel, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:1079–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumke R, von Baum H, Luck PC, Jacobs E. 2010. Occurrence of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains in Germany. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:613–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao B, Zhao CJ, Yin YD, Zhao F, Song SF, Bai L, Zhang JZ, Liu YM, Zhang YY, Wang H, Wang C. 2010. High prevalence of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates from adult and adolescent patients with respiratory tract infection in China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morozumi M, Takahashi T, Ubukata K. 2010. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae: characteristics of isolates and clinical aspects of community-acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. Chemother. 16:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardinale F, Chironna M, Dumke R, Binetti A, Daleno C, Sallustio A, Valzano A, Esposito S. 2011. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in paediatric pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 37:1522–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkinson TP, Boppana S, Theos A, Clements LS, Xiao L, Waites K. 2011. Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a boy with macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Pediatrics 127:e1605–e1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashyap S, Sarkar M. 2010. Mycoplasma pneumonia: clinical features and management. Lung India 27:75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki S, Yamazaki T, Narita M, Okazaki N, Suzuki I, Andoh T, Matsuoka M, Kenri T, Arakawa Y, Sasaki T. 2006. Clinical evaluation of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:709–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu P-S, Chang L-Y, Lin H-C, Chi H, Hsieh Y-C, Huang Y-C, Liu C-C, Huang Y-C, Huang L-M. 20 November 2012. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of children with macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in Taiwan. Pediatr. Pulmonol. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1002/ppul.22706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuoka M, Narita M, Okazaki N, Ohya H, Yamazaki T, Ouchi K, Suzuki I, Andoh T, Kenri T, Sasaki Y, Horino A, Shintani M, Arakawa Y, Sasaki T. 2004. Characterization and molecular analysis of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates obtained in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4624–4630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucier TS, Heitzman K, Liu SK, Hu PC. 1995. Transition mutations in the 23S rRNA of erythromycin-resistant isolates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2770–2773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waites KB, Balish MF, Atkinson TP. 2008. New insights into the pathogenesis and detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Future Microbiol. 3:635–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuckerman JM, Qamar F, Bono BR. 2011. Review of macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin), ketolids (telithromycin) and glycylcyclines (tigecycline). Med. Clin. North Am. 95:761–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada T, Morozumi M, Tajima T, Hasegawa M, Sakata H, Ohnari S, Chiba N, Iwata S, Ubukata K. 2012. Rapid effectiveness of minocycline or doxycycline against macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a 2011 outbreak among Japanese children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55:1642–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai Y, Miyashita N, Kubo M, Akaike H, Kato A, Nishizawa Y, Saito A, Kondo E, Teranishi H, Ogita S, Tanaka T, Kawasaki K, Nakano T, Terada K, Ouchi K. 2013. Therapeutic efficacy of macrolides, minocycline, and tosufloxacin against macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in pediatric patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:2252–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]