Abstract

While there is general agreement that vision and audition decline with aging, observations for the somatosensory senses and taste are less clear. The purpose of this study was to assess age differences in multimodal sensory perception in healthy, community-dwelling participants. Participants (100 females and 78 males aged 20–89 years) judged the magnitudes of sensations associated with graded levels of thermal, tactile, and taste stimuli in separate testing sessions using a cross-modality matching (CMM) procedure. During each testing session, participants also rated words that describe magnitudes of percepts associated with differing-level sensory stimuli. The words provided contextual anchors for the sensory ratings, and the word-rating task served as a control for the CMM. The mean sensory ratings were used as dependent variables in a MANOVA for each sensory domain, with age and sex as between-subject variables. These analyses were repeated with the grand means for the word ratings as a covariate to control for the rating task. The results of this study suggest that there are modest age differences for somatosensory and taste domains. While the magnitudes of these differences are mediated somewhat by age differences in the rating task, differences in warm temperature, tactile, and salty taste persist.

Keywords: Sensory aging, Pain, Temperature, Somatosensory, Taste

Introduction

There is general agreement in the literature as to findings for declines in vision and audition with age (Desai et al. 2001). Reports of age differences for touch, warming and cooling temperature, and pain (somatosensory), and taste are less clear (Guergova and Dufour 2011; Mojet et al. 2003; Mojet et al. 2005). While there have been several reports of varying degrees of age differences in sensory functioning from laboratory studies of the somatosensory senses (warming, cooling, and touch), there is great variation in the sensory testing procedures and, when applicable, derived performance measures. For example, investigators have assessed either sensory thresholds or suprathreshold measures or both threshold and suprathreshold measures. Most studies of sensory thresholds, the minimal stimulus that an individual perceives, typically report that older participants have higher thresholds than younger participants. Reports from studies of suprathreshold perception, on the other hand, are less consistent in their findings, perhaps related to some degree to differences in how suprathreshold performance is measured. Sources of variability in reports arise from different modes of psychophysical sensory testing (for example, number of test stimuli employed, spacing between sensory stimuli, and range of test stimuli). Further, different investigators have employed different testing methods when assessing specific modalities. For example, for the assessment of thermal perception, how large a surface area is tested, and what type of stimulation is used, such as contact thermode via a Peltier device (Heft and Robinson 2010; Kenshalo 1986), radiant heat to blackened skin (Procacci et al. 1970), or immersion in a water bath for warm testing (Moshiree et al. 2007). Other investigators have assessed different body locations in somatosensory (tactile, temperature, and pain) studies (central versus more distal locations (Essick et al. 2004; Guergova and Dufour 2011; Rath and Essick 1990; Stevens et al. 2003; Stevens and Choo 1996; Stevens and Choo 1998; Stevens and Patterson 1995) and glabrous versus hairy skin sites (Rath and Essick 1990)). Finally, several investigators have varied spatial and temporal characteristics of stimulation in studies of thermal pain (Edwards and Fillingim 2001; Lautenbacher et al. 2005).

Similarly for taste studies, findings from threshold studies typically report higher thresholds in older participants across taste qualities. However, findings from suprathreshold studies typically only demonstrate selective lesser sensitivity among older participants for certain modalities (most often bitter taste) when it occurs (Mojet et al. 2003). Taste studies oftentimes vary in which compounds were selected for testing the same taste qualities, the medium in which they are presented, the number of stimuli provided, the spacing between successive stimulus magnitudes, and the range of stimuli chosen (Mojet et al. 2003). Furthermore, in suprathreshold studies, investigators have reported a variety of performance measures of sensitivity, including slopes of psychophysical functions (growth of perceptual magnitude with stimulus magnitude increase), measures of discriminability such as the intraclass correlation (Weiffenbach et al. 1986) coefficients, and determination of the Weber ratio (the minimum noticeable level of sensory change with a systematic change in stimulus magnitude) (Gilmore and Murphy 1989; Murphy and Gilmore 1989).

While studies of the somatosensory and chemosensory thresholds typically report elevations in these measures among older participants irrespective to the variation in testing, suprathreshold studies are less consistent. As suggested, the variability in the findings may be due to the variety of sensory testing methodologies. This study sought to address gaps in the understanding of sensory aging by providing a consistent, rigorous psychophysical assessment of age differences in ratings of multimodal suprathreshold somatosensory and taste stimuli in the same participants. A major strength of this approach is that the same participants assessed stimuli from multiple sensory domains, warming and cooling temperature, pain, and taste, using the same cross-modality matching rating procedure. In addition, participants also rated words that describe different levels of sensation (very weak, weak, moderate, strong, and very strong sensations) using the same procedure and rating scale within each sensory domain testing session. The inclusion of the word-rating task in the study provides two important improvements to the suprathreshold sensory testing approach. First, the words provide verbal anchors for the rating of the relative magnitudes of sensations. For example, participants judged the magnitudes of sensations associated with the warming stimuli as well as the connoted sensations described by the phrases “very weak warm,” “strong warm,” etc., in the same context. Thus, the levels of sensations experienced by participants could be linked to verbal descriptions of those sensations (Heft and Parker 1984). Second, participants are providing repeated ratings of recognizable verbal stimuli and, as such, provide a control for the sensory-rating task.

Method

Subjects

One hundred and seventy eight medically healthy community-dwelling participants aged 20–89 years were recruited for participation in the sensory testing sessions. We purposively recruited at least 20 male and 20 female participants for each of four age categories at baseline: 20–29, 35–44, 65–74, and >75 years to ensure adequate numbers of subjects across the life span for analyses. The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board, and all participants were provided informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. Before acceptance for enrollment in the study, subjects were examined by a physician’s assistant under the supervision of a neurologist to rule out factors other than aging that would contribute to the results from the sensory testing. The screening included both thorough review of medical history and clinical examination.

Sensory stimuli

Participants judged the magnitudes of sensations associated with graded levels of cooling, warming, and painful thermal, tactile, and salty and sour taste stimuli in separate test sessions for each modality. The somatosensory (thermal and tactile) stimuli were applied to both glabrous skin (upper lip) and hairy skin (chin) sites at the mid-face of the face within the same testing session for each stimulus type.

Cooling, warming, and painful thermal stimuli

The cooling, warming, and heat pain stimuli were delivered with a three-layer Peltier contact thermode (Model LTS, Thermal Devices, Golden Valley, MN, USA) which delivered warming stimuli at a rate of 10 °C/s within the range of warming temperatures and cooling temperatures at between 4.0 °C/s (in the 50–25 °C range) and 2.5 °C/s (in the 25 to 10 °C range) with relatively high precision and control (Wilcox and Giesler 1984). The thermal probe was held in place with a clamp that was attached to a vertical rod extension of a weighted stand that was placed on a table situated in front of the seated subject. The height of the probe was adjusted to the height of the subject’s mouth. For each stimulus trial, the subject was instructed to place either their lip or chin in contact with the thermode, switching the location for each successive trial. Stimuli were presented every 30 s to either the lip or chin sites. The seven cooling (18–30 °C) and warming (36–44 °C) and six heat pain temperatures (43–51 °C) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Verbal stimuli and taste stimulus concentrations

| Words | Sodium chloride (M) | Citric acid (M) | Touch (mN) | Warm (°C) | Cool (°C) | Pain (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very weak | 0.056 | 0.001 | 0.392 | 36 | 30 | 43 |

| Weak | 0.1 | 0.0018 | 0.686 | 37 | 28 | 45 |

| Moderate | 0.18 | 0.003 | 1.569 | 38 | 26 | 47 |

| Strong | 0.3 | 0.0056 | 3.922 | 39 | 24 | 48 |

| Very strong | 0.56 | 0.01 | 9.804 | 40.5 | 22 | 49 |

| 1.0 | 0.018 | 19.608 | 42 | 20 | 51 | |

| 1.8 | 0.03 | 58.824 | 44 | 18 |

Tactile (touch) stimuli

The tactile stimuli were applied with calibrated nylon monofilaments, Semmes-Weinstein filaments, that were applied at a 90° angle to the skin and distended to provide a standard, calibrated force to the skin (Weinstein 1962). The stimuli were alternately delivered to the upper lip and the chin at the mid-face. The seven tactile force levels (0.392–58.824 mN) are listed in Table 1.

Taste stimuli

Participants rated salty (sodium chloride) and sour (citric acid) taste stimuli in separate testing sessions. Ten ml of each of the seven concentrations of the sodium chloride (0.056–1.8 M) or the citric acid (0.001–0.03 M) solution was provided for each trial (test concentrations listed in Table 1). Participants were instructed to sip the fluid, swish it in their mouth, and expectorate into the sink. After the completion of each trial presentation and rating, participants rinsed their mouths with 10 ml of distilled water.

Verbal descriptors

Within each sensory testing session, participants also rated the magnitudes of percepts connoted by each of five words that describe different levels of sensations associated with the sensory stimuli. The words were very weak, weak, moderate, strong, and very strong, and the words were printed on 5 × 7 in. cards. The verbal descriptors were randomly presented within the sensory-stimulus-rating trials, and participants were instructed to apply the adjectives to the stimulus set session so that, for example, in the cooling temperature session, the descriptors signified very weak cool, weak cool, etc. Participants rated the magnitudes of percepts described by the words using the same rating methodology they used for judging magnitudes of sensations associated with the sensory stimuli.

Sensation and verbal descriptor assessments

Participants rated three trials of each of the seven sensory stimuli (six for pain) and five words in each sensory testing session. For both the tactile and thermal somatosensory stimuli, the 21 (18 for pain) sensory stimuli were applied to both the lip and chin sites. So, for each tactile, warming, and cooling session, each participant rated 21 (18 for pain) stimuli applied to the lip, 21 (18 for pain) stimuli applied to the chin, and 15 word stimuli or 57 trials (51 trials for pain). The test stimuli were block-randomized so that the participant received one trial of each of the sensory and word stimuli before receiving the second and then third presentation of each stimulus. Thus, participants rated the first trial of the full range of the sensory and verbal stimuli prior to the second and the full range of the sensory and verbal stimuli for the second trial prior to the third.

Sensory and verbal descriptor measurements

Participants rated each stimulus presentation in a cross-modality matching procedure in which they matched sensations and sensations described by the words to the length of an extended tape measure. They were informed prior to the presentation of each somatosensory (warming, cooling, pain, and tactile) stimulus presentation. For each sensory and word stimulus presentation, participants were instructed to extend the length of a retractable tape measure (Sears/Craftsman Posilock Tape, No. 39406) that was mounted at the end of a piece of board (8.9 × 3.8 × 76.2 cm) to a distance that matched the magnitude of the sensation (Weiffenbach et al. 1986) or the magnitude of percept described by the word. The numerical markings on the tape measure in millimeters were viewed and recorded by the research assistant, while the blank underside of the tape was viewed by the subject. Participants were further instructed to extend the tape so that the length of the tape reflected the relative magnitudes of the sensations or percept.

Data analysis

For analyses, data from the 100 female and 78 male participants were divided into two age groups, “<45 years” and “≥65 years,” based on a bimodal distribution split at age 50 years (ninety-two “<45 years” and eighty-six “≥65 years”). Data from each sensory modality (and stimulation site for the tactile and warming, cooling, and pain temperature conditions) were collapsed to obtain a mean rating for each modality. The mean sensory ratings were used as dependent variables in a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for each sensory domain, with age and sex as between-subject variables. To assess whether any results from analyses reflected differences in response bias rather than sensory differences, the MANOVAs were repeated with the grand means for the word ratings serving as a covariate.

Results

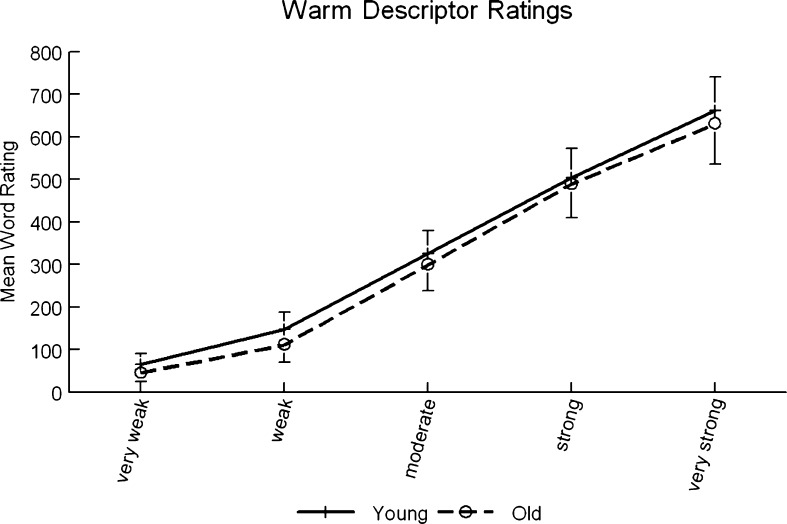

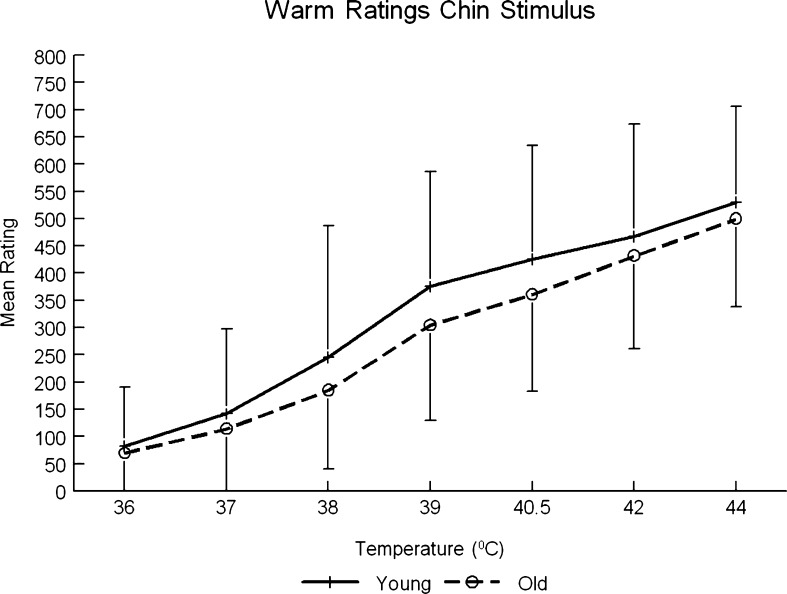

Figures 1 and 2 show group data for younger (<45 years) and older (≥65 years) for the mean word ratings for each of the five verbal descriptors (Fig. 1) and for the mean ratings for the heat pain stimuli applied to the chin site (Fig. 2). These figures demonstrate that participants could reliably perform the rating task, i.e., they rated successive words that connoted greater sensation and also successive heat stimuli of increasing temperature as greater amounts in the cross-modality matching procedure. Further, as expected, they rated the word stimuli more consistently than the sensory stimuli.

Fig. 1.

The group mean ratings for each of the five verbal descriptors (1 = very weak, 2 = weak, 3 = moderate, 4 = strong, and 5 = very strong) for “<45 years” (lines, n = 92) and “≥65 years” (dashed lines, n = 86) participants are plotted as functions of the words. Each data point represents the mean rating for three trials for each of the five words (for “<45 years,” n = 276 ratings, and for “≥65 years,” n = 258 ratings)

Fig. 2.

The group mean ratings for the sensations evoked by seven warm/hot thermal stimuli applied to the chin for “<45 years” (lines, n = 92) and “≥65 years” (dashed lines, n = 86) participants are plotted as functions of stimulus temperatures. Each data point represents the mean rating for three trials for each of the seven temperature levels (for “<45 years,” n = 276 ratings, and for “≥65 years,” n = 258 ratings)

Analyses of sensory-rating data

Data for each sensory modality were collapsed to obtain a mean rating for each stimulation site (lip, chin) where applicable. These mean ratings were used as dependent variables in a MANOVA for each sensory domain, with age and sex as between-subject variables.

The summary of the analyses is provided in Table 2, column 2. There were no age or sex differences in the ratings of the pain stimuli. However, there were age differences in the assessment of all other sensory stimuli (p < 0.001). The younger (<45 years) participants rated the warm and cool temperature, touch, and sour and salty taste stimuli as more intense than the older (≥65 years) participants. Further, for warm, women rated the stimuli as more intense than males.

Table 2.

Analyses of age and sex differences in ratings of sensory stimuli and verbal descriptors

| Modality | Analyses of sensory data | Word ratings | Repeat analyses of sensory data controlling for rating task |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Non-significant | F(2,171) = 13.7,p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.14 | Non-significant |

| Warm | Age: F(2,172) = 15.7, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.15 | F(2,173) = 52.4, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.38 | Age: F(2,173) = 4.9, p = 0.008, eta2 = 0.05 |

| Sex: F(2,172) = 3.7, p = 0.03, eta2 = 0.04 | |||

| Cool | Age: F(2, 171) = 9.1, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.1 | F(2,172) = 112, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.56 | Age: Non-significant F(2,172) = 1.5, p = 0.23, eta2 = 0.017 |

| Touch | Age: F(1,174) = 20.7, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.19 | F(2,175) = 41.8, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.32 | Age: F(2,175) = 5.5, p = 0.005, eta2 = 0.06 |

| Sour | Age: F(1,170) = 14.6, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.08 | F(1,171) = 58.5, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.26 | Age: Non-significant F(1,171) = 1.3, p = 0.246, eta2 = 0.008 |

| Salt | Age: F(1,170) = 28.6, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.14 | F(1,171) = 80.3, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.32 | Age: F(1,171) = 10.1,p = 0.002, eta2 = 0.06 |

Repeat analyses of sensory-rating data controlling for (word) rating task

To test the hypothesis that older participants tended to have a more stoic response set and scale use, the previously reported ANOVAs for suprathreshold stimuli were conducted with the grand mean of word ratings for each sensory modality as a covariate.

Older individuals rated the verbal descriptors significantly less than the younger individuals for each of the sensory modalities (all p < 0.001, see Table 2, column 3). For all sensory domains, controlling for verbal descriptor ratings moderates the sensory ratings in the same direction (reducing the observed age effect). In the reanalyses with the word-rating covariates (ANCOVAs), age differences remained for three modalities (Table 2, column 4). Younger (<45 years) participants rated warm (p = 0.008), touch (p = 0.005), and salty stimuli (p = 0.002) as more intense than older participants. The magnitudes of these effects were diminished in magnitude, suggesting that the stoic scale bias (i.e., younger participants tend to rate the words as greater than older participants) attenuated the age effect. As before, there were no age differences in the ratings of painful stimuli. However, the previously observed age differences for cool temperature and sour taste as well as the sex differences in warm temperature ratings were not preserved. The results are parallel by site, with the ratings at the lip site for the somatosensory stimuli greater than the chin site for all but cool stimulation.

Discussion

The results of this study support the belief that there are differences in sensory functioning between older and younger individuals for several somatosensory and taste domains. Since study participants underwent medical and neurological screening prior to inclusion at baseline, we were able to control for health contributions that might contribute to the findings. A strength of this study was that participants assessed multiple somatosensory and taste domains using a common cross-modality matching psychophysical testing procedure. Furthermore, the inclusion of multiple sensory domains provides a more global context for evaluating sensory performance. Results from the initial analyses (before controlling for the rating task) suggested that the younger participants (age <45 years) rated warming and cooling temperatures, touch, and sour and salty taste stimuli as more intense than older participants. There were no observed differences in pain perception. Sex differences were only observed for warm perception, whereby young females rated warm stimuli as greater than younger males.

An important feature of the study design was that participants rated words that describe different levels of sensations associated with percepts within the context of the sensory testing procedures. The adjectives very weak, weak, moderate, strong, and very strong readily describe different levels of sensation readily associated with temperature, touch, taste, and painful stimuli. As such, the words provided a calibration control for participants’ sensory ratings which is lacking in direct ratings of sensory stimuli (Stevens and Marks 1980).

A further strength of this study is that the inclusion of the non-sensory-rating procedure, judging the connoted magnitudes of the verbal stimuli, provides a relevant control for the sensory-rating task. This is important because it has been suggested that presumed individual differences in sensory functioning from psychophysical rating procedures might result from more cautious ratings by older individuals (Botwinick 1984) and response factors rather than sensory differences (Rule and Curtis 1982). Rule and Curtis (1982) proposed a two-stage model in which individual differences might arise from differences in sensory processing of stimulus information or might arise from differences in response factors including how individuals use the response scales or both of these factors.

For all sensory domains, the younger participants rated the verbal descriptors as greater than the older participants. This suggests that there is an age bias in the rating task—younger participants tend to rate stimuli as more intense. When the data were reanalyzed with the word rating serving as a covariate, age differences were noted for warming temperature, touch, and salty taste, although their magnitudes were less than determined previously. Further, there were no differences for pain, cooling temperature, or sour taste, and previously observed sex difference for warming temperature was eliminated. These findings support the view that observed age differences in sensory assessment of suprathreshold sensory stimuli are likely related to the rating task rather than sensory performance. Furthermore, the suprathreshold results are in contrast to the consistent finding of elevations in thresholds with age for all of these sensory domains in these participants (Heft and Robinson 2010).

The observed age differences in somatosensory perception may be related to changes in skin, peripheral nervous system, or central nervous system (for review, see Guergova and Dufour 2011). Skin changes that might impact thermal or tactile perception include loss of elastin, collagen, and subcutaneous fat. These changes would influence the dispersal of heat or cold from thermal stimulation. The structural changes also impact the integrity and resilience of skin in response to the tactile stimuli.

Most taste complaints are likely related to flavor, the integration of the senses of taste and smell, and are likely indicative of smell deficits (Pritbitkin et al. 2003; Spielman 1998). Taste disorders are less common than other sensory disorders due to the robust innervation of taste receptors by four cranial nerves and the relatively rapid turnover of taste receptors (Sandow et al. 2006). Smell disorders, on the other hand, are more common due to the fact that olfaction is mediated by one cranial nerve and the receptors have much slower turnover rate. Schiffman has indicated that older adults are more susceptible to taste disorders because systemic diseases and especially medications may induce taste sensations directly, impacting the peripheral receptors or the chemosensory neural pathways (Schiffman 2009).

The results of this study suggest that there are modest age differences for somatosensory and taste domains. While the magnitudes of these differences are mediated somewhat by age differences in the rating task, differences in warm temperature, tactile, and salty taste persist. Future studies should address the potential roles of changes in skin integrity, peripheral nervous system, and cognitive factors in these findings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants DE08845 and DE11398 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Botwinick J. Aging and behavior. 3. New York: Springer; 1984. pp. 200–202. [Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Pratt LA, Lentzner H, Robinson KN. Trends in vision and hearing among older Americans. Aging trends. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Effects of age on temporal summation and habituation of thermal pain: clinical relevance in healthy older and younger adults. J Pain. 2001;2:307–317. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.25525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essick G, Guest S, Martinez E, Chen C, McGlone F. Site-dependent and subject-related variations in perioral thermal sensitivity. Somatosens Mot Res. 2004;21:159–175. doi: 10.1080/08990220400012414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore MM, Murphy C. Aging is associated with increased Weber ratios for caffeine, but not sucrose. Percept Psychophys. 1989;46:555–559. doi: 10.3758/BF03208152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guergova S, Dufour A. Thermal sensitivity in the elderly: A review. Aging Res Rev. 2011;10:80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heft MW, Parker SR. An experimental basis for revising the graphic scale for pain. Pain. 1984;19:153–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heft MW, Robinson ME. Age differences in orofacial sensory thresholds. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1102–1105. doi: 10.1177/0022034510375287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenshalo DR. Somesthetic sensitivity in young and elderly humans. J Gerontol. 1986;41:732–742. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.6.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbacher S, Kunz M, Strate P, Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L. Age effects on pain thresholds, temporal summation and spatial summation of heat and pressure pain. Pain. 2005;115:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojet J, Heidema J, Christ-Hazalhof E. Taste perception with age: generic or specific losses in supra-threshold intensities of five taste qualities? Chem Senses. 2003;28:397–413. doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.5.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojet J, Heidema J, Christ-Hazalhof E, Heidema J. Taste perception with age: pleasantness and its relationships with threshold sensitivity and suprathreshold intensity of five taste qualities. Food Qual Prefer. 2005;16:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moshiree B, Price DD, Robinson ME, Gaible R, Verne GN. Thermal and visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome patients with and without fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:323–330. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318032e496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Gilmore MM. Quality-specific effects of aging on the human taste system. Percept Psychophys. 1989;45:121–128. doi: 10.3758/BF03208046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritbitkin E, Rosenthal MD, Cowart BJ. Prevalence and causes of severe taste loss in a chemosensory clinic population. Ann Oto Rhinol Laryn. 2003;112:971–978. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procacci P, Bozza G, Buzzelli G, Della Corte MD. The cutaneous pricking pain threshold in old age. Gerontol Clin. 1970;12:213–218. doi: 10.1159/000245281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath EM, Essick GK. Perioral somesthetic sensibility: Do the skin of the lower face and midface exhibit comparable sensitivity? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1181–1190. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rule SJ, Curtis DW. Levels of sensory and judgmental processing: strategies for the evaluation of a model. In: Wegener B, editor. Social attitudes and psychophysical measurement. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1982. pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sandow PL, Hejrat-Yazdi M, Heft MW. Taste loss and recovery following radiation therapy. J Dent Res. 2006;85:608–611. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman SS. Effects of aging on the human taste system. In: Finger TE, editor. International symposium on olfaction and taste. 2009. pp. 725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman AI. Chemosensory function and dysfunction. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:267–291. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JC, Alvarez-Reeves M, Dipietro L, Mack GW, Green BG. Decline of tactile acuity in aging: A study of body site, blood flow, and lifetime habits of smoking and physical activity. Somatosens Mot Res. 2003;20:271–279. doi: 10.1080/08990220310001622997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JC, Choo KK. Spatial acuity of the body surface over the life span. Somatosens Mot Res. 1996;13:153–166. doi: 10.3109/08990229609051403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JC, Choo KK. Temperature sensitivity of the body surface over the life span. Somatosens Mot Res. 1998;15:13–28. doi: 10.1080/08990229870925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JC, Marks LE. Cross-modality matching functions generated by magnitude estimation. Percept Psychophys. 1980;27:379–389. doi: 10.3758/BF03204456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JC, Patterson MQ. Dimensions of spatial acuity in the touch sense—changes over the life span. Somatosens Mot Res. 1995;12:29–47. doi: 10.3109/08990229509063140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiffenbach JM, Cowart BJ, Baum BJ. Taste intensity perception in aging. J Gerontol. 1986;41:460–468. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein S. Tactile sensitivity of the phalanges. Percep Motor Skill. 1962;14:351–354. doi: 10.2466/pms.1962.14.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox GL, Giesler GJ. An instrument using a multiple layer peltier device to change skin temperature rapidly. Brain Res Bull. 1984;12:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]