Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alcohol use disorder is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. Despite the availability of efficacious treatments, few individuals with an alcohol use disorder are actively engaged in treatment. Available evidence suggests that primary care may play a crucial role in the identification of patients with an alcohol use disorder, delivery of interventions, and the success of treatment.

OBJECTIVE

The principal aims of this study were to test the effectiveness of a primary care-based Alcohol Care Management (ACM) program for alcohol use disorder and treatment engagement in veterans.

DESIGN

The design of the study was a 26-week single-blind randomized clinical trial. The study was conducted in the primary care practices at three VA medical centers. Participants were randomly assigned to treatment in ACM or standard treatment in a specialty outpatient addiction treatment program.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred and sixty-three alcohol-dependent veterans were randomized.

INTERVENTION

ACM focused on the use of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial support. ACM was delivered in-person or by telephone within the primary care clinic.

MAIN MEASUREMENTS

Engagement in treatment and heavy alcohol consumption.

KEY RESULTS

The ACM condition had a significantly higher proportion of participants engaged in treatment over the 26 weeks [OR = 5.36, 95 % CI = (2.99, 9.59)]. The percentage of heavy drinking days were significantly lower in the ACM condition [OR = 2.16, 95 % CI = (1.27, 3.66)], while overall abstinence did not differ between groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Results demonstrate that treatment for an alcohol use disorder can be delivered effectively within primary care, leading to greater rates of engagement in treatment and greater reductions in heavy drinking.

KEY WORDS: addiction, primary care, treatment, randomized clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide.1 Despite the associated morbidity and mortality, most individuals suffering from an alcohol use disorder do not receive treatment, with less than 15 % of individuals receiving specialized alcohol treatment.2 In addition, only 36 % of individuals complete treatment.3

Primary care providers (PCPs) are encouraged to screen and initiate treatment for excessive drinking and alcohol use disorders.4 This model is consistent with the view of primary care as a patient-centered medical home, and is aligned with efforts to integrate psychiatric and behavioral health into the medical home. A number of controlled clinical trials and meta-analyses suggest that brief alcohol interventions (BAIs) with primary care patients who engage in “at risk” or harmful alcohol consumption are efficacious.5,6 This model of care is widely known as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT).7 However, there is little evidence that BAIs improve outcomes or access to specialty care for individuals with moderate to severe alcohol use disorders.

Within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system, there has been substantial success in implementing screening, with over 95 % of veterans screened annually and a large number receiving brief advice. However, VA patients with a positive depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) screen are ten times more likely to receive treatment than a patient with a positive alcohol screen.8 Moreover, only 3.4 % of patients with an alcohol use disorder are prescribed naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram.9 Finally, it is widely recognized that most of the patients who are referred to specialty care do not attend; thus, attention has been shifted to developing treatments that may be applicable to primary care. It is estimated that 2.8 % of veterans screen at the higher end of the severity for an alcohol use disorder and could potentially benefit from treatment.10

Willenbring et al. demonstrated the efficacy of integrated care in medically ill patients with alcohol dependence.11 Integrated Outpatient Treatment (IOT) focused on alcoholism as a chronic disease, with a goal of increasing function by changing behavior. Patients who received this treatment had higher abstinence rates compared to patients in the control group who were offered an appointment in an addiction program. More recently, two open label treatment studies showed that naltrexone used in primary care settings was a promising approach.12,13 Naltrexone in particular may be considered a first line treatment, as it has few side effects and is dosed only once per day. Naltrexone has been demonstrated in recent studies14,15 and meta-analyses16–18 to significantly reduce drinking days and the number of heavy drinking days.

Alcohol Care Management (ACM) was developed by combining aspects of depression care management, the experience from the Willenbring et al. model, and a treatment model developed for the delivery of addiction pharmacotherapy.11,19 Specifically, ACM relies on the availability of a behavioral health provider (BHP) working in the primary care team and trained to deliver personalized and measurement based addiction care.

The purpose of this study was to test the effectiveness of the ACM model of care to engage and maintain participants in treatment and reduce alcohol consumption. It was predicted that ACM would lead to greater engagement in treatment and less heavy drinking compared to patients referred to standard specialty care. If successful, ACM could either be a first line treatment or an alternative to specialty care for individuals who have limited access to or refuse specialty care.

METHODS

Trial Design and Participants

The study was a 26-week single blind randomized clinical trial of ACM versus referral to standard addiction outpatient specialty care (SC). Eligible participants were at least 18 years old, met DSM-IV criteria for current alcohol dependence, and drank greater than an average of two standard drinks per day in the 60 days prior to randomization. Participants were excluded if they demonstrated current abuse or dependence on illicit drugs or opioids, exhibited symptoms of dementia, psychosis, or mania, or were actively engaged in SC. There were no exclusions for depression or anxiety disorders, or current prescription medication use. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Philadelphia and Syracuse VA Medical Centers (VAMC), and participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Recruitment

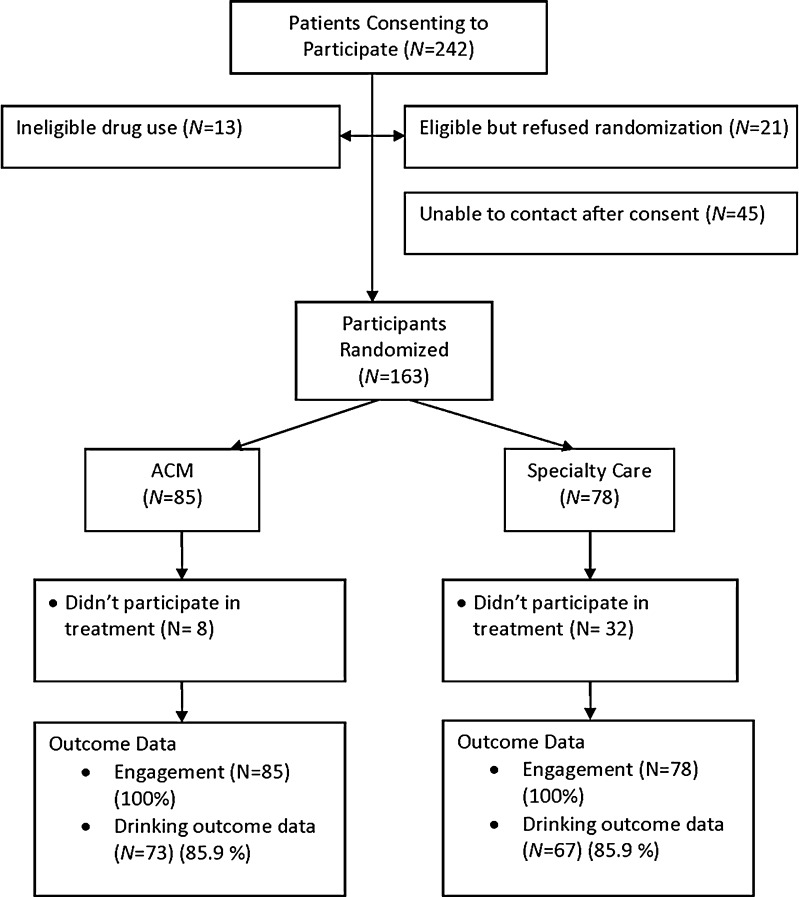

Participants were referred to the study by primary care providers from one of three VAMCs (two in New York and one in Philadelphia), through existing integrated care programs. Recruitment occurred between October 2007 and June 2008. Primary care providers (PCPs) referred patients to the integrated care program based on their own clinical judgment, patient request, or results of structured alcohol screening.20 ACM was developed to be assimilated into integrated care programs, which are clinical programs for delivering evidence-based mental health care in primary care.21 The integrated care program starts by offering a rapid assessment for depression, alcohol use disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, and drug use. At the completion of the clinical assessment, eligible veterans were offered research participation. The initial treatment appointment in each arm was scheduled within 14 days of randomization. Recruitment and retention of participants are shown in the CONSORT Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment and participation from referral to study completion.

Interventions

Alcohol Care Management (ACM)

The main goal of ACM was to engage subjects in treatment and reduce their alcohol consumption. The BHP acted as a physician extender to the primary care team. The BHP communicated all assessment and treatment plan recommendations to the PCP through the medical record and verbal communication as needed. The BHP assessed for medical complications of alcohol use and made recommendations for further treatment.

Key Features of Alcohol Care Management (ACM)

After the initial ACM visit, participants met weekly with their BHP for 30 min. If participants were unable to attend an in-person session, the session was conducted by telephone covering the same content and meeting for the same duration as the face-to-face sessions. As participants improved, the frequency of visits could be reduced to twice per month after the first 3 months. During each session, the BHP assessed use of alcohol, encouraged treatment adherence, offered support and education, and monitored for new or worsening medical problems. The BHP provided individualized education about alcohol use disorders as a treatable problem. The BHP educated the participant about pharmacotherapy, the dosing regimen, how to watch for and manage potential side effects, and how to prevent medication noncompliance. Each BHP was trained in motivational interviewing techniques and the use of action plans focused on achievable goals for the participant each week. The goals could be drinking goals as well as other health care or life goals (e.g. walking, nutrition, etc.). While ACM promotes the goal of abstinence, it differs from 12-step programs in that participants set their own drinking reduction goals, with abstinence as one option. For ACM participants, depression and anxiety were managed concurrently by the BHP using defined care management strategies.21

Initial Treatment with Naltrexone

In his/her role, the BHP would promote the use of evidence-based pharmacotherapy. For this project, we promoted the use of naltrexone, because it was on the formulary within the VA system. Participants who otherwise had no contraindications were offered treatment with naltrexone (50 mg). Use of naltrexone was not a requirement of participation.

Training and Supervision

Prior to the study, each BHP was trained and certified to deliver ACM following guidelines developed for the Combing Medications and Behavioral Interventions (COMBINE) study.22 For this study, we utilized psychologists or mental health registered nurses experienced in integrated care as the BHPs. The training consisted of lectures, reading, and the provision of care to at least one participant not in the study, which was audiotaped and rated for fidelity to the model. Throughout the study, the BHPs participated in weekly group supervision led by an addiction nurse practitioner trained in the ACM model. A random selection of audiotapes from sessions was listened to in supervision and discussed as a mechanism to avoid therapeutic drift and fidelity to the model. There was no evidence of drift over the course of the trial.

Standard Specialty Care (SC)

For participants assigned to SC, an appointment was provided to the participant at the VA specialty outpatient addiction program located at the host medical center. The PCP was notified of this appointment through the clinical record as an alert.

SC at the participating Medical Centers was based on a 12-step facilitation model. Treatment interventions included assessments and evaluations, outpatient detoxification, counseling (individual, family, and group), pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, psycho-educational groups, outreach and referral, and acupuncture (one site only). In all programs, participants started in an intensive outpatient program (IOP) consisting of two to four half-day treatment sessions for up to 6 weeks. At the conclusion of IOP, participants were enrolled in ongoing group therapy one to two times per week with ancillary services as needed. Participants were also expected to attend Alcoholics Anonymous, but attendance was not tracked or mandatory. Pharmacotherapy (naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram) was available in the specialty clinics.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of participants engaged in clinical services during each month of the intervention. Treatment engagement was tracked using the VA electronic medical record supplemented by a questionnaire of services received outside the VA. The two treatment models differed substantially in the expectation for attendance, with once weekly sessions in ACM and three to four times per week in SC. To compare the two groups on a similar scale, we created binary monthly indicators of attending at least two addiction treatment visits. In addition, a research assistant (RA) blind to treatment assignment collected self-reported outcome assessments at 3 and 6 months post-randomization. The measure of drinking outcome was the Time Line Follow-Back (TLFB).23,24 Drinking reports were recorded for the 60 days preceding enrollment, as well as during the intervention. Quantity of alcohol was recorded in standard drinks. For each month of the intervention, we considered outcomes as the: presence/absence of heavy drinking and presence/absence of any drinking. Heavy drinking was defined as five or more drinks in a single day for men, four or more for women.25–27 Additional outcome assessments included the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP);28 the contemplation ladder;29 and the Short Form–12 (SF12), which were also done at baseline.30 The SIP is a measure of alcohol-related problems and the SF12 is a measure of quality of life with a physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) domain.

Sample Size

The sample size was chosen to be able to detect a moderate sized group difference in engagement rates between the groups. We used a baseline rate of 30 % engagement in the SC group, based on national VA performance data. On the assumption of a within-subject correlation of 0.5, a sample size of 75 per group provided 80 % power for a difference of 17 %: this sample size was increased by 10 % to allow for variation in the intervention effect across sites, yielding a final planned sample size of 82 per group.31

Randomization

Participants were randomly allocated to the two intervention groups separately within each site, using blocked randomizations with a block size of ten. The randomization lists were created by Dr. Lynch using PROC PLAN in SAS prior to the start of the study.

The scheduling of participants after randomization was done by staff not involved in the care of participants or in the assessment of outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of ACM and SC were compared using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables. Repeated monthly measures of treatment engagement and drinking outcomes were compared using generalized estimating equation models (GEE).31 In all GEE models, a pre-treatment version of the response was included as a covariate, together with a binary indicator for intervention group (SC versus ACM), a binary indicator for site, and a linear trend for time. Quadratic and higher order trends for the time effect, as well as group by time and site by time interactions, were also assessed for inclusion in the models. The significance of the interaction terms was evaluated based on p values from score tests in the GEE models. A compound symmetry structure was used for the working correlation matrix, and empirical (robust) standard errors were used. Continuous measures of drinking were analyzed after log transformation. Secondary outcomes were also compared using GEE models. Pattern mixture models comparing completers and non-completers were used to assess the sensitivity of the primary TLFB models to missing data.32,33

RESULTS

There were 242 potential participants, referred by primary care providers, who consented to participate. Of these, 163 were randomized (see Fig. 1 for CONSORT diagram). Table 1 provides general characteristics of the randomized sample. There were no missing data for the primary outcome of engagement and no differences between groups in the percent providing drinking data (X2 = 0.00, p = 1.00). There was a significant association between dropout and site, with 15/23 dropouts from the one of the New York sites (X2 = 18.09, p < 0.001), with no association between intervention and dropout in either site (X2 < 0.02, p > 0.90 in each site). A logistic regression model predicting dropout showed that only race (X2 < 4.57, p = 0.03) and SF12 PCS (X2 = 4.64, p = 0.03) were significantly associated with dropout: for race, African-American participants were more likely to complete the study; for the SF12-PCS, higher scores were associated with completion [OR = 1.06, 95 % CI = (1.004, 1.127)].

Table 1.

Demographic and Pretreatment Clinical Characteristics of Randomized Sample

| Alcohol Care Management (n = 85) | Specialty Care (n = 78) | Test statistic | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.86 (11.43) | 57.07 (10.07) | χ2 kw = 1.61 | p = 0.20 |

| Male (%) | 85 (100 %) | 73 (93.59 %) | χ2 p = 5.62 | p = 0.02 |

| Caucasian (%) | 35 (41.18 %) | 34 (43.59 %) | χ2 p = 0.10 | p = 0.76 |

| Employed (%) | 30 (35.29 %) | 20 (25.64 %) | χ2 p = 1.38 | p = 0.19 |

| Recruitment site (% New York) | 24 (28.24 %) | 22 (28.21 %) | χ2 p = 0.00 | p = 1.00 |

| % Days Heavy Drinking | 54.47 (53.78) | 54.70 (33.62) | χ2 kw = 0.00 | p = 0.97 |

| % Days Drinking | 69.38 (28.10) | 71.97 (28.93) | χ2 kw = 0.71 | p = 0.40 |

| Drinks/Drinking Day | 9.04 (5.01) | 8.80 (4.54) | χ2 kw = 0.01 | p = 0.93 |

| Contemplation Ladder (0–10) | 7.40 (2.59) | 6.96 (2.48) | χ2 kw = 1.69 | p = 0.19 |

| Prior history of addiction treatment | 53 (62.4 %) | 51 (65.4 %) | χ2 p = 0.88 | p = 0.46 |

| SIP score | 6.15 (4.10) | 5.40 (3.71) | χ2 kw = 1.11 | p = 0.29 |

| PHQ-9 Score | 9.52 (6.18) | 10.42 (7.54) | χ2 kw = 0.25 | p = 0.62 |

| PACS score | 14.24 (8.70) | 14.59 (7.87) | χ2 kw = 0.05 | p = 0.82 |

| PCS - SF12 | 44.65 (10.48) | 44.32 (9.95) | χ2 kw = 0.05 | p = 0.83 |

| MCS - SF12 | 41.22 (13.70) | 40.91 (9.95) | χ2 kw = 0.01 | p = 0.91 |

| % with PTSD | 26 (30.59 %) | 18 (23.08) | χ2 p = 1.16 | p = 0.28 |

| % who are current smokers | 40 (47.06 %) | 43 (55.13 %) | χ2 p = 1.06 | p = 0.30 |

Values represent means (standard deviations) for continuous measures and cell counts (percentages) for categorical measures. Continuous variables compared using Kruskal-Wallis test, and categorical measures compared using Pearson Chi-square test

PCS Physical Component Score from the Medical Outcomes scale (SF36)

MCS Mental Component Score from the Medical Outcomes scale (SF36)

SIP Short Inventory of Problems

PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire (0–27 with higher scores indicating greater depression)

Alcohol use prestudy represents the 60-day period prior to consent

Treatment Engagement Outcome Measure

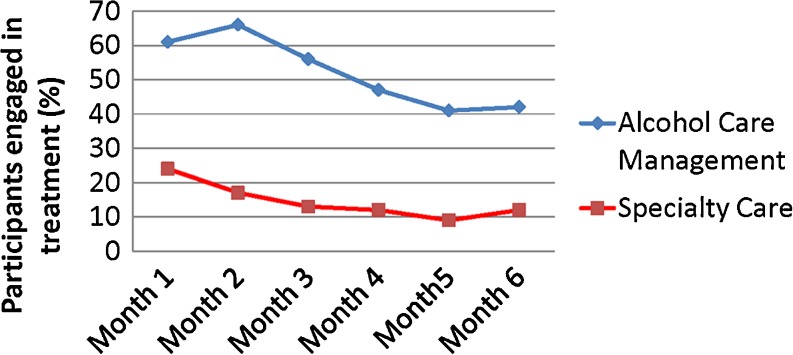

The average number of visits made for SC participants was 3.79 (SD = 6.64), while the average number was 10.25 (SD = 6.98) in the ACM group. Among participants who made at least one visit over the 6-month period, the average number of visits for the SC participants was 6.43 (SD = 7.63), while the average number for the ACM participants was 11.31 (SD = 6.45). Neither the treatment by time [chi-square(1) = 0.01, p = 0.94] nor the treatment by site [chi-square(1) = 2.79, p = 0.09] interaction was significant. As shown in Fig. 2, there was a significant main effect for the intervention [chi-square(1) = 48.43, p < .0001], with the ACM group more likely to make at least two visits in a given month than the SC group [OR = 6.97, 95 % CI = (4.04, 12.05)]. Among those participants interviewed at the 6-month point, there were no reports of addiction treatment received outside of the VA. As a secondary measure of fidelity to the ACM model and engagement of treatment, we compared the groups on the proportion of participants who were treated with naltrexone. Naltrexone was prescribed in 56/85 (65.9 %) of the participants in the ACM group and 9/78 (11.5 %) of those in the SC group [chi-square(1) = 50.10, p < 0.0001]. Of note, only one participant reported exposure to naltrexone prior to participation in this study. There were no prescriptions for acamprosate or disufiram in any study participant.

Figure 2.

Treatment engagement as determined by the percentage of participants who had two or more addiction-related treatment visits in a given month.

Drinking Outcome Measures

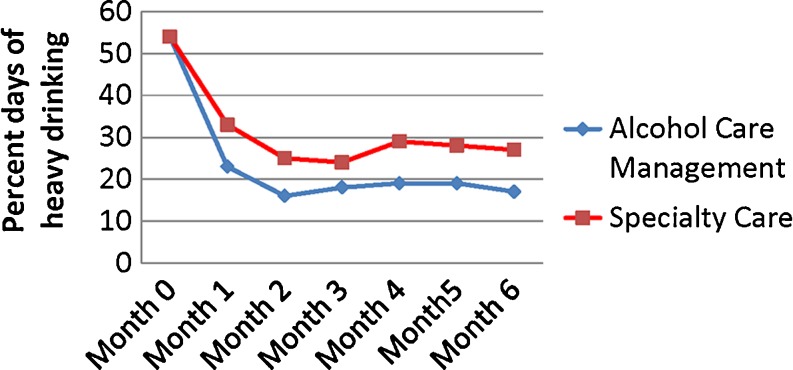

The models for drinking outcomes included baseline percent days heavy drinking as a covariate. For presence/absence of heavy drinking, neither the intervention by time [chi-square(1) = 0.72, p = 0.40] nor the intervention by site [chi-square(1) = 1.28, p = 0.26] interaction was significant.

As shown in Fig. 3, there was a significant main effect for the intervention [chi-square(1) = 8.24, p = 0.004], with the ACM group more likely to refrain from heavy drinking in any given month than the SC group [OR = 2.16, 95 % CI = (1.27, 3.66)]. There were no significant intervention by time [chi-square(1) = 0.09, p = 0.76], intervention by site [chi-square(1) = 1.13, p = 0.29], or intervention effects for presence/absence of any drinking [chi-square(1) = 1.13, p = 0.29; OR = 1.40, 95 % CI = (0.75, 2.59)].

Figure 3.

Group means of the percent days of heavy drinking from baseline throughout treatment.

In pattern mixture models, there were no significant interactions between a binary indicator of completion status and intervention group, time, or site, for any of the primary TLFB outcomes, indicating that missing data did not significantly affect the analyses.31

Secondary Outcomes

There was a significant main effect for the intervention [chi-square(1) = 4.60, p = 0.03] for the SF12 PCS scale, with the ACM group having higher values (better outcomes) than the SC group [BETA = 2.64, 95 % CI = (0.28, 4.99)]. Secondary measures of motivation (contemplation ladder) [chi-square(1) = 2.06, p = 0.15; Beta = 0.44, 95 % CI = (−0.16, 1.05)], and alcohol related problems (SIP TOTAL) [chi-square(1) = 3.83, p = 0.05, Beta = −1.16, 95 % CI = (−2.30, −0.02)] all favored the ACM group, though none was significant. There was no significant main effect for the SF12 MCS [chi-square(1) = 0.00, p = 0.97, Beta = −0.07, 95 % CI = (−3.08, 2.95)].

DISCUSSION

The ACM model of care led to greater reductions in heavy drinking days and greater treatment engagement. Secondary outcomes also showed favorable improvement in physical health functioning. Based on the results, the ACM model can be considered a first line treatment for patients with an alcohol use disorder. However, there may be some with an alcohol use disorder who would do better with the intensive level of care typically delivered by specialty addiction treatment, particularly those with concurrent active illicit drug disorders.

One limitation of this study is that its results may not generalize to settings outside the Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare system. The VA has been committed over the last several years to developing the medical home concept of primary care, and has promoted the delivery of mental health care collaboratively with primary care. Study clinics also used standardized screening for hazardous drinking as a part of routine care. Thus, it is possible that the use of systematic screening or the established presence of an integrated behavioral health program biased results towards the ACM arm. As the study was conducted in VAMCs, copayment, access to appointments, and shared medical records were similar in both arms of the study. The ACM model requires further study in primary care-based medical home models outside the VA, but the model is not inherently designed for veterans and can be exported to other sites.

The findings of the study also raise questions about the lack of use of addiction pharmacotherapies in specialty addiction care and general psychiatry. There was a large disparity in prescribing between the two arms, which is likely due to the emphasis on pharmacotherapy within the ACM arm. Recent evidence underscores the low use of addiction pharmacotherapy in the VA system, with only 3.4 % of those with alcohol dependence prescribed a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pharmacotherapy.9

In summary, the results offer an effective alternative treatment for patients with an alcohol use disorder. Given the high rates of disability associated with a moderate to severe alcohol use disorder, healthcare institutions should consider adopting programs such as ACM that can facilitate treatment access and improve health. Further research should focus on the model’s long-term effects, cost savings, generalizability, and for whom this intervention might be most effective. Given the demands on clinical time within primary care settings, research on implementation barriers should also be a focal point of future research.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

We thank the primary care providers who fully participated in the study and their dedication to improving outcomes for addictive disorders.

Funders

Supported, for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, by the following sources:

• Health Services Research and Development Program of the Department of Veteran Affairs (IIR)

• The VISN 4 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center

• The VISN 2 Center for Integrated Healthcare

• Career Development Award [K05 AA16928 (Dr. Maisto)]

• NIDA (K24 DA029062) and NIAAA (P01-AA016821) (Dr. McKay)

Prior Presentations

There have been no prior presentations of the outcome data.

Conflicts of Interest

Potential conflicts of interest include funding from the Caron Foundation (McKay); Hazelden Foundation (Oslin and McKay); Treatment Research Institute (McKay), University of Wisconsin (McKay), Wright State University (McKay), Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene (McKay), National Quality Forum (McKay), Altarum (McKay), the State of Pennsylvania (Oslin, Lynch) and the Human Service Center (McKay). The remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Clinicaltrials.gov - NCT00419315

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray C, Lopez A. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. In: Murray C, Lopez A, editors. The global burden of disease and injury series, Vol. 1. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen E, et al. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2–3):214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, O.o.A.S., Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2005. Discharges from substance abuse treatment services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

- 4.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:554–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Poikolainen K. Effectiveness of brief interventions to reduce alcohol intake in primary health care populations: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 1999;28:503–9. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moyer A, et al. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97:279–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babor TF, et al. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maust DT, et al. Missed opportunities: fewer service referrals after positive alcohol misuse screens in VA primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(3):310–2. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris AH, et al. Pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorders by the Veterans Health Administration: patterns of receipt and persistence. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):679–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kivlahan DR. Outcomes from AUDIT screen throughout the VA system., D. Oslin, Editor 2013.

- 11.Willenbring ML, Olson DH. A randomized trial of integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(16):1946–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.16.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor PG, et al. A preliminary investigation of the management of alcohol dependence with naltrexone by primary care providers. Am J Med. 1997;103(6):477–82. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JD, et al. Extended-release naltrexone for treatment of alcohol dependence in primary care. J Subst Abus Treat. 2010;39(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiefer F, et al. Pharmacological relapse prevention of alcoholism: clinical predictors of outcome. Eur Addict Res. 2005;11(2):83–91. doi: 10.1159/000083037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garbutt J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;293:1617–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maisel NC, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bouza C, et al. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99(7):811–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oslin D, ed. Foundations for Integrated Care. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013.

- 20.Bradley KA, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1842;22(8):1842–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tew J, Klaus J, Oslin DW. The Behavioral Health Laboratory: building a stronger foundation for the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):130–45. doi: 10.1037/a0020249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettinati H, et al. Medical management treatment manual: a clinical research guide for medically trained clinicians providing pharmacotherapy as part of the treatment for alcohol dependence 2004. Bethesda, MD: NIAAA, DHHS Publication # 04-5289.

- 23.Sobell L, et al. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 1992. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anton R. New methodologies for pharmacological treatment trials for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:3A–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volpicelli JR, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence.[see comment] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(11):876–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kranzler HR, et al. Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate for alcoholism treatment: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(9):1335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller W, Tonigan J, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): an instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Vol. Vol. 4. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10(5):360–5. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item Short-form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;32:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diggle P, et al. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford Statistical Science Series #252002, New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

- 32.Molenberghs G, Verbeke G. Models for discrete longitudinal data. Statistics2005: Springer.

- 33.Verbeke G, MG. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. Statistics2000: Springer.