Abstract

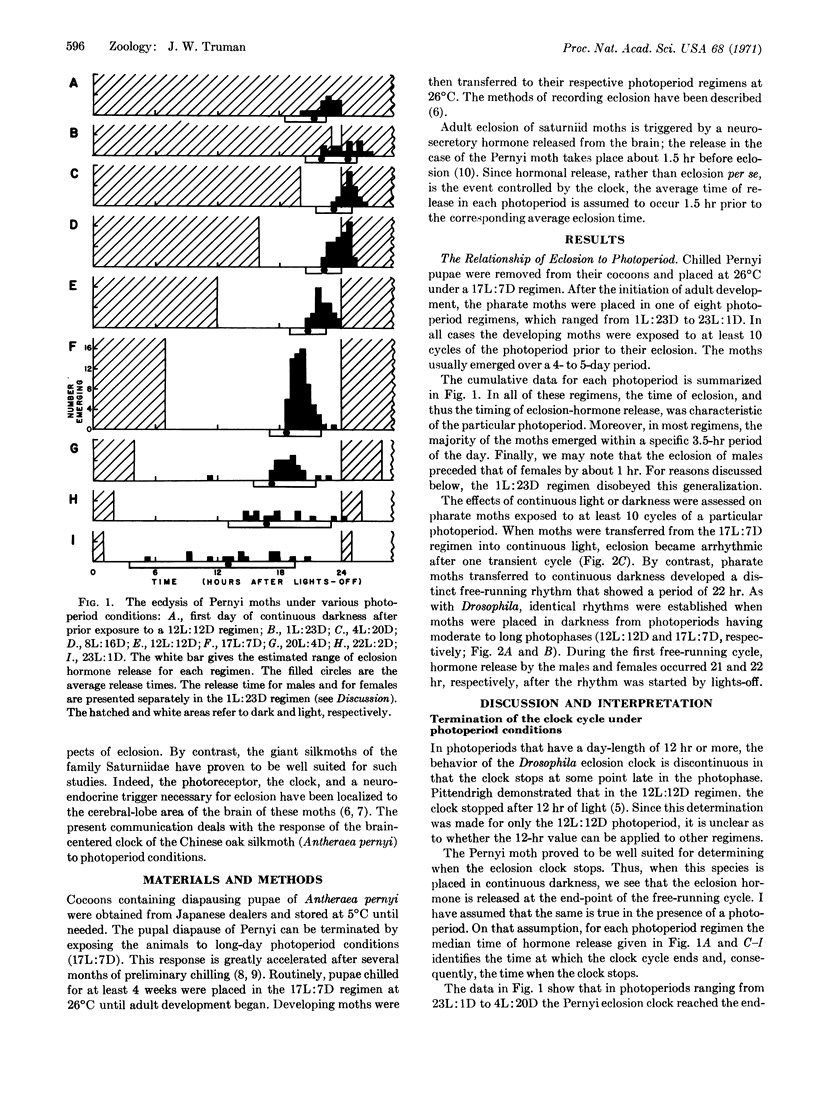

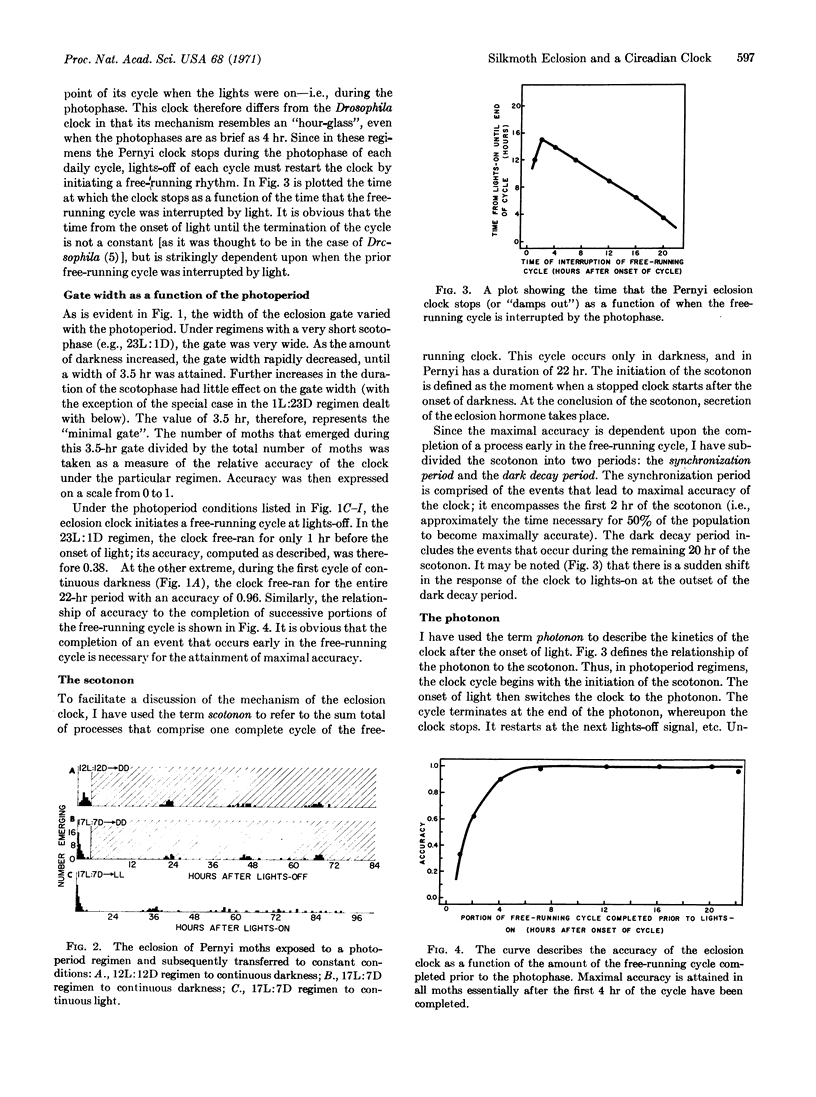

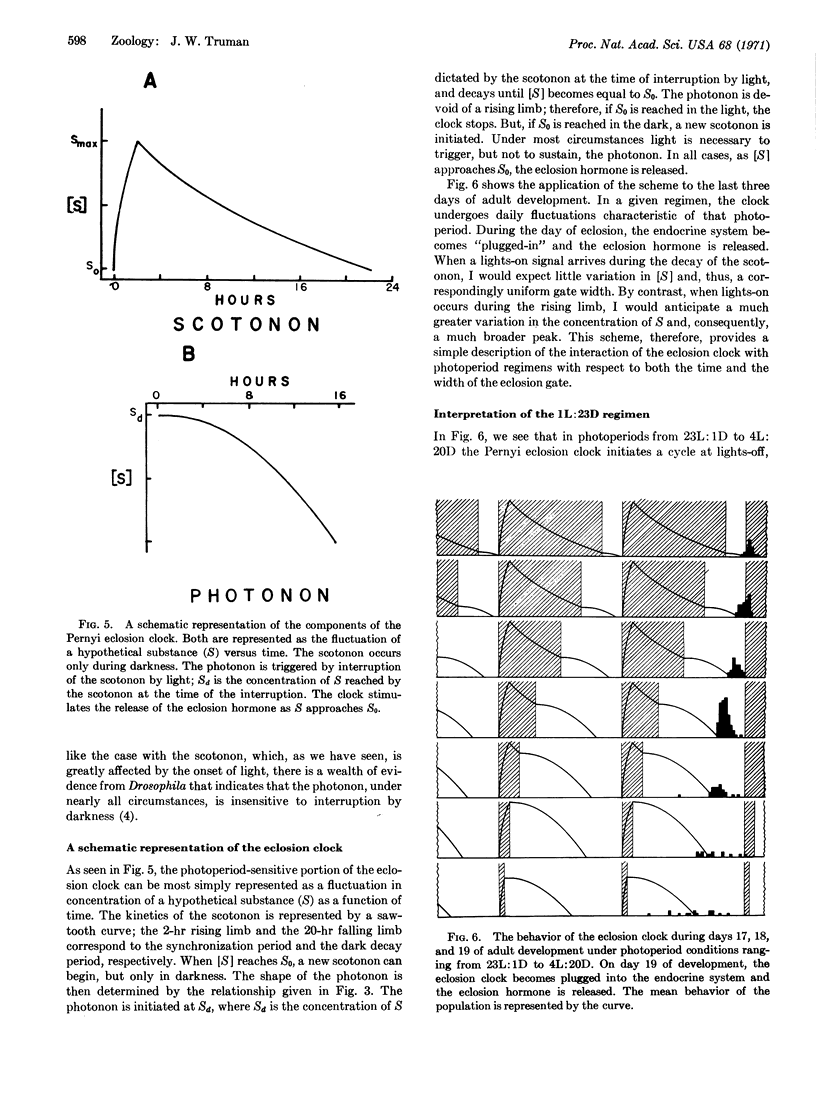

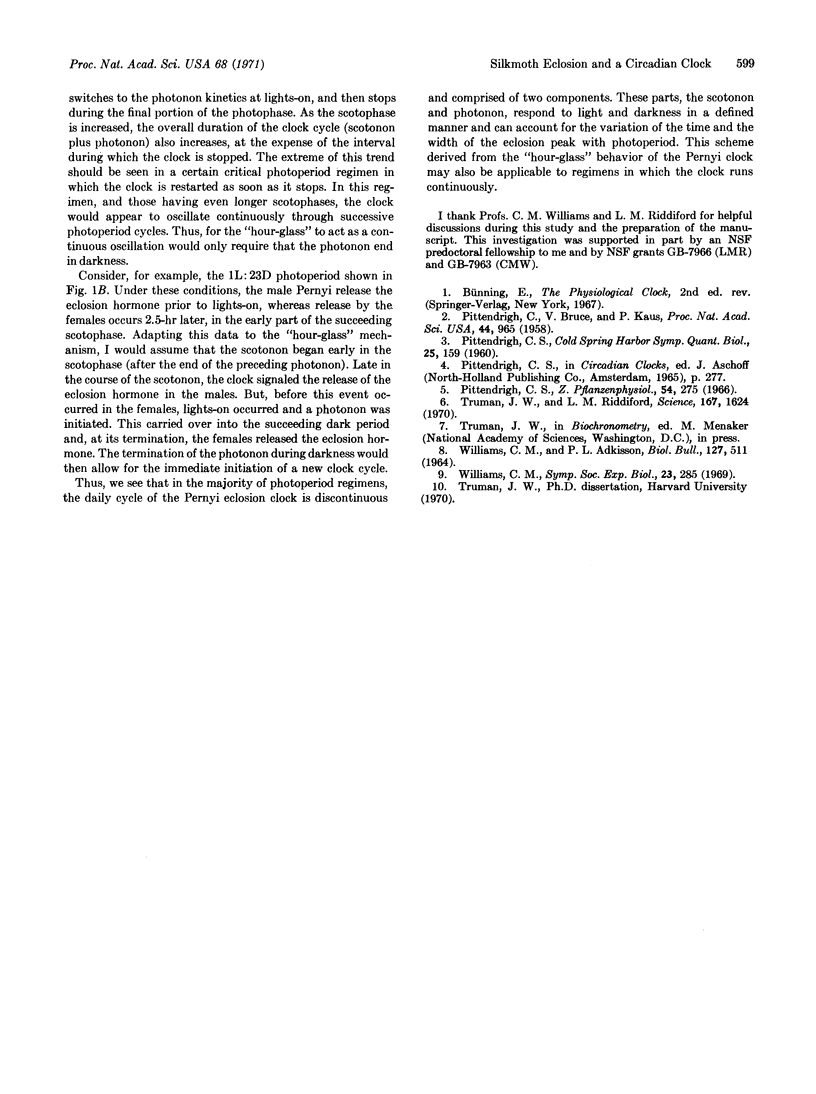

The emergence of the Pernyi silkmoth from the pupal exuviae is dictated by a brain-centered, photosensitive clock. In continuous darkness the clock displays a persistent free-running rhythm. In photoperiod regimens the interaction of the clock with the daily lightdark cycle produces a characteristic time of eclosion. But, in the majority of regimens (from 23L:1D to 4L:20D), the eclosion clock undergoes a discontinuous “hourglass” behavior. Thus, during each daily cycle, the onset of darkness initiates a free-running cycle of the clock. The next “lights-on” interrupts this cycle and the clock comes to a stop late in the photophase. The moment when the Pernyi clock stops signals the release of an eclosion-stimulating hormone and is demonstrated to be a function of the time when the free-running cycle is interrupted by lights-on. Moreover, the width (duration) of the eclosion peak in a photoperiod is shown to be dependent upon the length of the dark phase, and, consequently, upon the amount of the free-running cycle that is completed. This relationship demonstrates that the free-running cycle may be divided into two parts. The attainment of maximal accuracy (and thus the narrowest eclosion peak) is dependent upon the completion of only the first 2 hr of the free-running cycle. The completion of succeeding portions of the cycle, while having an effect upon the time of eclosion, no longer affects the accuracy of the clock. A mechanistic model of the eclosion clock is presented.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- PITTENDRIGH C. S. Circadian rhythms and the circadian organization of living systems. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1960;25:159–184. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1960.025.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh C., Bruce V., Kaus P. ON THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TRANSIENTS IN DAILY RHYTHMS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1958 Sep 15;44(9):965–973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.9.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman J. W., Riddiford L. M. Neuroendocrine control of ecdysis in silkmoths. Science. 1970 Mar 20;167(3925):1624–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3925.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. M. Photoperiodism and the endocrine aspects of insect diapause. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1969;23:285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]