Abstract

Objective

To assess the outcome and associated risks of atrial defragmentation for the treatment of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation (LSP-AF).

Methods

Thirty-seven consecutive patients (60.4 ± 7.3 years; 28 male) suffering from LSP-AF who underwent pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) and linear ablation were compared. All patients were treated with the Stereotaxis magnetic navigation system (MNS). Two groups were distinguished: patients with (n = 20) and without (n = 17) defragmentation. The primary endpoint of the study was freedom of AF after 12 months. Secondary endpoints were AF termination, procedure time, fluoroscopy time and procedural complications. Complications were divided into two groups: major (infarction, stroke, major bleeding and tamponade) and minor (fever, pericarditis and inguinal haematoma).

Results

No difference was seen in freedom of AF between the defragmentation and the non-defragmentation group (56.2 % vs. 40.0 %, P = 0.344). Procedure times in the defragmentation group were longer; no differences in fluoroscopy times were observed. No major complications occurred. A higher number of minor complications occurred in the defragmentation group (45.0 % vs. 5.9 %, P = 0.009). Mean hospital stay was comparable (4.7 ± 2.2 vs. 3.4 ± 0.8 days, P = 0.06).

Conclusion

Our study suggests that complete defragmentation using MNS is associated with a higher number of minor complications and longer procedure times and thus compromises efficiency without improving efficacy.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Complex fractionated atrial electrograms, Catheter ablation, Persistent atrial fibrillation

Introduction

Currently, catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) in which the pulmonary veins (PVs) are electrically isolated is a well-accepted treatment and has proven to be successful [1–3]. However, the efficacy of PV isolation (PVI) alone in long-standing persistent AF (LSP-AF) is poor [4]. Whereas the single procedure drug-free success rate of PVI in paroxysmal AF ranges between 57 and 80 % [5–8], in contrast PVI in LSP-AF offers rather low success rates (21–22 %) [9–11]. Additional ablation lines and other techniques have been proposed to increase the success rate of LSP-AF ablation, one of these being atrial defragmentation [12]. During this procedure electrogram-based ablation is performed. Treatment targeting specific areas in the atrial substrate, showing complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAEs), has also been proposed [13]. Although successful termination of AF by using this technique alone has been reported, others have not replicated the encouraging results of this study [14]. The benefit of PVI and additional linear ablation in the treatment of LSP-AF has been shown in several studies [4, 12, 15]. It remains unclear if a combination of PVI and CFAE ablation significantly increases the success rate of LSP-AF ablation as opposed to PVI and linear ablation [4, 16].

The aim of this study was to assess whether complete defragmentation is a useful additional technique in order to achieve a satisfactory clinical outcome in the treatment of LSP-AF.

Methods

This study was a retrospective data analysis. Data from 37 consecutive patients (age 60.4 ± 7.3 years; 28 male) diagnosed with LSP-AF were compared. Before all procedures a transoesophageal echo was performed to exclude left atrial (LA) thrombus. Twenty-six patients underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation for AF at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and 11 patients were treated at the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. However, the same team of electrophysiologists performed all the procedures at two different locations using identical equipment and procedure strategies. During the procedure, activated clotting time (ACT) levels were monitored and were required to be between 275 and 350 s. Patients were divided into two groups: LA ablation (PVI and linear ablation) with and without defragmentation. Data on outcome and post-procedural complications were collected. The primary endpoint of the study was freedom of AF after 12 months. Secondary endpoints were the following: acute AF termination, procedure time, fluoroscopy time and (post) procedural complications. Complications were divided into two categories: major and minor. Major complications were defined as: acute myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and tamponade. Minor complications included: fever, pericarditis and inguinal haematoma.

Study population

Only patients with LSP-AF, defined as AF being persistent for 12 months or longer, were included (Table 1) [17]. Exclusion criteria for this study were: fever or infection, renal failure (on dialysis or at risk of requiring dialysis, serum creatinine >200 μmol/l), a malignancy needing therapy or a life expectancy shorter than the duration of the study. Additional exclusion criteria were intracardiac thrombus, severe cerebrovascular disease (neurological deficit of cerebrovascular cause that persists beyond 24 h), active gastrointestinal bleeding, bleeding or clotting disorders or inability to receive heparin and intractable heart failure (NYHA class IV).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and procedural parameters

| Defragmentation | No defragmentation | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 20 | 17 | |

| Age (years) | 59.2 ± 7.7 | 61.8 ± 6.8 | p = 0.28 |

| Male sex (n), (%) | 13 (65.0 %) | 15 (88.2 %) | p = 0.10 |

| Years of AF (y) | 5.7 ± 6.1 | 5.6 ± 4.4 | p = 0.95 |

| Repeat procedures (n), (%) | 6 (30.0 %) | 2 (11.8 %) | p = 0.17 |

| Class III antiarrhythmics (n), (%) | 13 (65.0 %) | 15 (88.2 %) | p = 0.10 |

| Mean LA diameter (mm) | 47.4 ± 5.5 | 45.1 ± 4.9 | p = 0.21 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 47.8 ± 13.9 | 52.3 ± 13.1 | p = 0.66 |

| Mean procedure time (min) | 332.5 ± 78.3 | 261.1 ± 96.6 | p = 0.02 |

| Mean fluoroscopy time (sec) | 58.3 ± 25.8 | 49.6 ± 20.8 | p = 0.33 |

Lastly, patients with an allergy to contrast, patients with uncontrolled diabetes (fasting blood glucose ≥10.0 mmol/l), pregnant patients or women of child-bearing potential not using a highly effective method of contraception and patients who were unable to attend the outpatients clinic were excluded from the study. The institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up for 12 months. They attended outpatient appointments after 3, 6 and 12 months. An ECG was obtained at every visit. Before the procedure, a standard echo and a transoesophageal echo were performed. Data from the transthoracic echo was used to measure the left ventricular ejection fraction. Three months before and 12 months after the procedure, patients were fitted with a 24-hour ambulatory ECG device. The first month before and the third month after the procedure, patients received a transtelephonic cardiac event monitor, which they wore for 1 week. Every day patients submitted their ECG and were instructed to send extra recordings if they experienced any symptoms. After the first 3 months an assessment was made regarding the use for antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs). At 6 and 12 months after the procedure the need for anticoagulants was reassessed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient follow-up timeline

| Before/after PVI | Time | Activity (ECG on every visit) |

|---|---|---|

| Before | 3 months | 24-hour Holter registration |

| 1 month | Transtelephonic cardiac event monitor | |

| 1 day | Standard echo, transoesophageal echo, standard blood work | |

| After | 3 months | Clinical visit, event recorder, AAD check up |

| 6 months | Clinical visit, assessment anticoagulants | |

| 12 months | Assessment anticoagulants, 24-hour Holter registration |

AAD antiarrhythmic drugs

Treatment arms

PVI with defragmentation

All patients were treated with the Niobe Stereotaxis, Magnetic Navigation System (MNS) (Stereotaxis Inc., St. Louis MO, USA). The use of this system has been extensively described in previous reports [18, 19]. Every patient was treated under general anaesthesia because of the long procedure times and rather extensive and potentially painful ablation. Invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring was mandatory throughout the procedure. Pre-ablation 3D images (CT or MRI) were not routinely used as it was not considered essential for the procedures.

Both groins were prepared for puncture. Intracardiac echocardiography guided transseptal puncture was performed. Two 8.5 F SL1 (or SL0) sheaths were introduced into the left atrium. A decapolar catheter was placed into the coronary sinus. A Lasso catheter (Biosense Webster Inc., Diamond Bar, CA, USA) was inserted into the left atrium via one transseptal sheath. Using the second transseptal sheath a magnetic irrigated-tip mapping and ablation catheter (RMT Navistar, Biosense Webster Inc., Diamond Bar, CA, USA) was inserted in the left atrium.

The left atrium was extensively mapped (density: min 350 equally distributed points) using the MNS system. All PVs were mapped as separate chambers. Special attention was paid to the accurate definition of the PV ostia. The ablation sequence adhered to the following: First all PVs were isolated. Then electrogram-based ablation (i.e. defragmentation) in the left atrium and the coronary sinus was performed at all sites that displayed any of the following electrogram features: CFAEs, sites with a significant electrogram offset between distal and proximal recording bipoles of the mapping catheter suggesting a local re-entrant wavefront and regions with a cycle length (CL) shorter than the mean LA appendage CL. Specific CFAE maps using dedicated software were not performed.

Endpoint of ablation was in the transformation of fractionated electrograms into discrete electrograms and slowing of the mean atrial CL compared with LA appendage CL or the elimination of the electrograms in each region. If AF still persisted, linear ablation was performed: First a roof line, then a mitral line and lastly a posteroinferior line. The right atrium and superior vena cava were targeted for ablation if suspected to be a source perpetuating AF (lesser prolongation of CL in the right atrium, resulting in left-right fibrillatory CL gradient) and only after all LA ablation steps. Endpoint was the elimination or significant reduction (>75 %) of the local electrograms along the ablation lines. After restoration of sinus rhythm, bidirectional block was assessed at every line using differential pacing methods. Arrhythmia induction was not part of this protocol. In case of conversion to a regular atrial tachycardia, this was targeted for ablation in the same session.

Power settings were conservatively and individually adjusted (note: these settings are valid only for ablation using the MNS). In all regions 25 W, 48°, and 30 s with an irrigation rate of 17 ml was used as initial setup. The bipolar and unipolar local electrograms were carefully and continuously monitored during and after every ablation application. If the local electrical activity persisted, the following adjustments were made: posterior wall: max 35 W, anterior wall: max 40 W, carina, or other ridge-like structures: max 45 W. At difficult regions ablation time was extended to 45 s. Thirty minutes after the last application all PVs were revisited to confirm electrical isolation.

PVI without defragmentation

The same sequence as aforementioned was used, with the exception that after PVI and additional line ablation defragmentation was not performed.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of distribution. Descriptive statistics was presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables if normally distributed. Continuous data were compared with the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test, where appropriate. Categorical data were presented as percentages and compared with the Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analysis was performed with PASW version 18 (IBM Corp., Somers, NY). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Patient population

A total of 37 patients were included. The defragmentation group had 20 patients and 17 patients were included in the non-defragmentation group. No differences in age, gender, years of AF, number of repeat procedure and use of class III antiarrhythmics were noted (Tables 1 and 3). For the repeat procedures, a mean number of 1.75 ± 1.75 [range 0–4] PVs needed to be reisolated. The mean LA diameter of the whole population was 46.4 ± 5.3 mm. No difference in mean LA diameter was seen between the two groups (P = 0.214, Table 1). Furthermore, there was no difference in left ventricular ejection fraction between the treatment arms (Table 1). The mean number of electrical cardioversions in the whole population was 3.6 ± 3.0. No differences were seen between the defragmentation and the non-defragmentation group (3.2 ± 2.1 vs. 4.0 ± 3.7; p = 0.404, respectively).

Table 3.

Use of antiarrhythmics before and after procedure

| Defragmentation | No Defragmentation | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | |||

| Amiodarone (n), % | 10 (50 %) | 13 (76.5 %) | 23 (62.2 %) |

| Sotalol (n), % | 5 (25.0 %) | 6 (35.3 %) | 11 (29.7 %) |

| After | |||

| Amiodarone (n), % | 12 (63.2 %) | 12 (70.6 %) | 24 (66.7 %) |

| Sotalol (n), % | 4 (21.1 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | 7 (19.4 %) |

Ablation data

Procedure times in the defragmentation group were longer and the use of fluoroscopy was comparable between both groups (Table 1). The mean number of applications for the total group was 134.2 ± 69.6. A significant difference in the mean number of applications was seen between the defragmentation group and the non-defragmentation group (161.9 ± 74.1 vs. 96.5 ± 41.4, P = 0.014). Mean radiofrequency application time from the whole group was 3438 ± 1664 s. No difference in mean application time was reported between the defragmentation group and the non-defragmentation group (3947 ± 1782 vs. 2837 ± 1350 s, P = 0.105). Furthermore, no differences were observed between the two groups in acute AF termination (70.0 % vs. 76.5 %: P = 0.474).

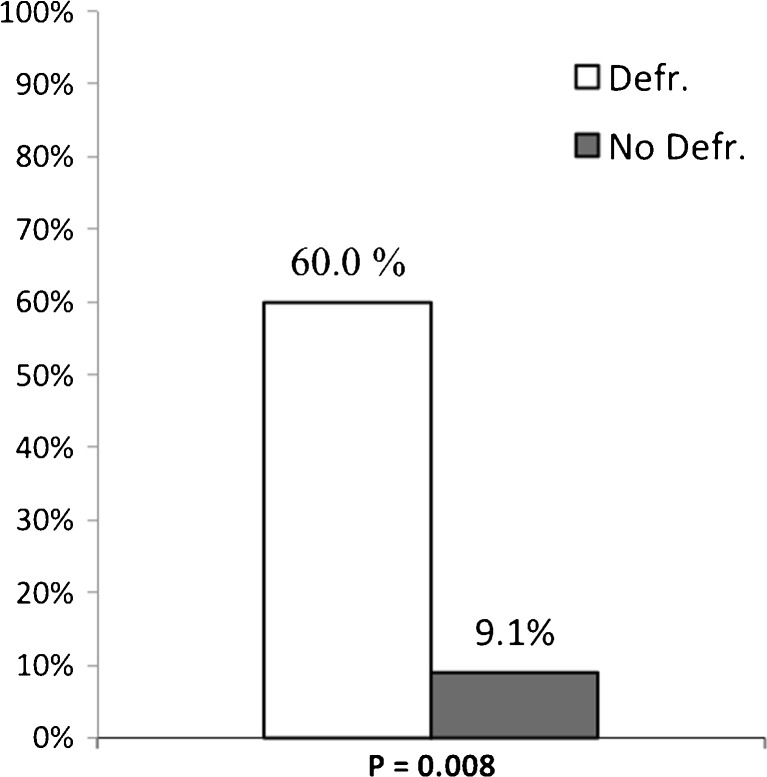

Complications

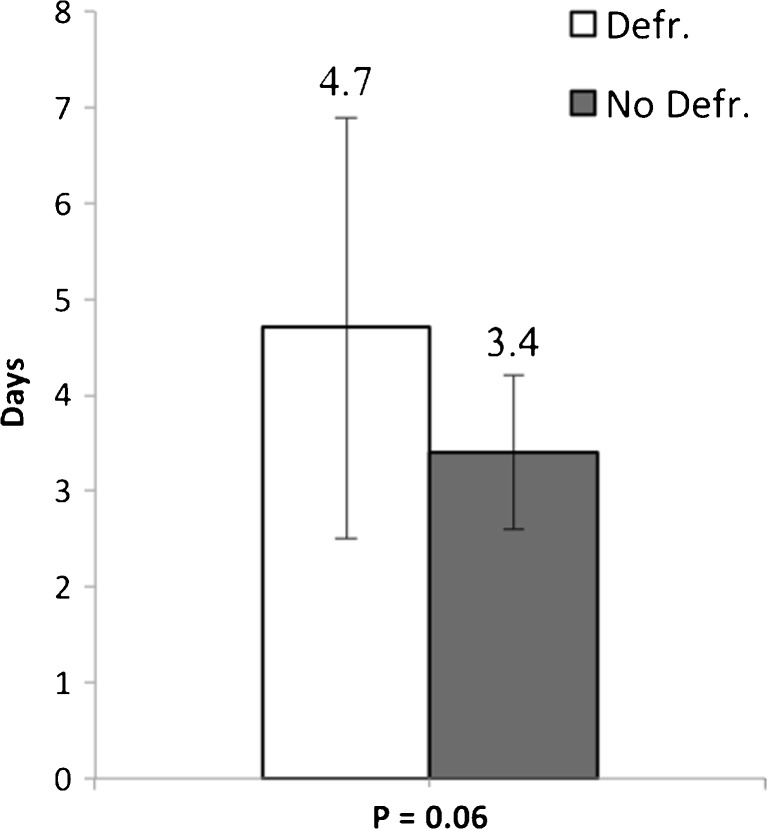

No major complications occurred in any of the patients. A significantly higher occurrence of minor complications was seen in the defragmentation group (45.0 % vs. 5.9 %, P = 0.009) (Fig. 1). No difference in type of minor complications was seen. Patients who experienced complications received a significantly higher number of radiofrequency (RF) applications (173.7 ± 69.9 vs. 109.6 ± 58.8, P = 0.019). Of all patients, 8.1 % (n = 3) had inguinal haematoma, 8.1 % (n = 3) had mild pericardial effusion, 5.4 % (n = 2) had fever and 2.7 % (n = 1) had pericardial effusion and fever. In the defragmentation group, 10.0 % (n = 2) had inguinal haematoma, 15.0 % (n = 3) had mild pericardial effusion, 10.0 % (n = 2) had fever and 5.0 % (n = 1) had mild pericardial effusion and fever. In the non-defragmentation group 1 (5.9 %) patient had inguinal haematoma. There was no difference in mean hospital stay between the defragmentation group and the non-defragmentation group (4.7 ± 2.2 vs. 3.4 ± 0.8, P = 0.06) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of minor complications for both the defragmentation and non-defragmentation group

Fig. 2.

Average hospital stay presented with standard deviation for patients in the defragmentation and non-defragmentation group

Follow-up

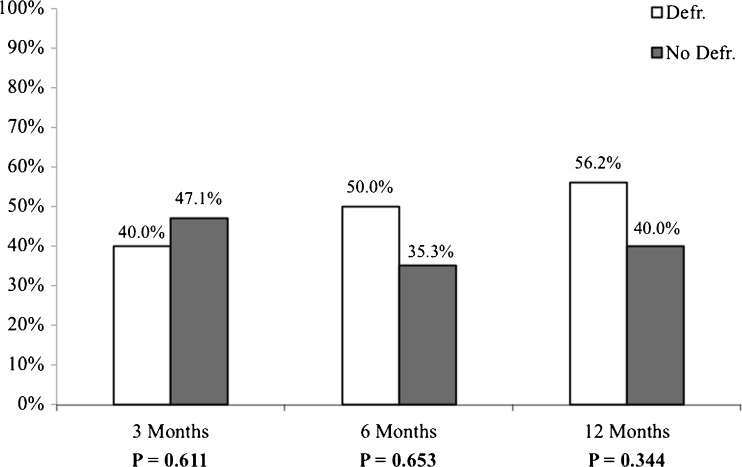

For all three moments in time during follow-up (3, 6 and 12 months) no difference was observed in freedom of AF between the two groups (Fig. 3). After 3 months, 40.0 % of the patients in the defragmentation group were still in sinus rhythm, whereas in the non-defragmentation group this was 47.1 % (P = 0.611). At 6 months, the number of patients in sinus rhythm was 50.0 % vs. 35.3 % (P = 0.653). After completion of 12 months of follow-up 56.2 % of the patients from the defragmentation group were in sinus rhythm and 40.0 % of the patients in the non-defragmentation group (P = 0.344). During follow-up the use of AADs was comparable for the two groups (70.0 % vs. 76.5 %, P = 0.474) (Table 3). In 13.5 % (n = 5) of the patients a repeat procedure was performed during follow. During electrophysiology (EP) study one patient had reconduction in both the left inferior and right superior PV, another in the right superior PV, another in the left superior PV, one patient had reconduction of all PVs and in one patient all PVs were isolated and additional defragmentation needed to be performed only. During follow-up, 24.3 % of the total population experienced atrial tachycardia. This was not statistically different when compared among the defragmentation and non-defragmentation group (11.8 % vs. 35.0 %, P = 0.103).

Fig. 3.

The number of patients in sinus rhythm during follow-up. Data from three moments in time are presented (3, 6 and 12 months)

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the use of complete defragmentation using magnetic navigation in addition to conventional PVI and linear ablation. The major finding is that defragmentation for the ablation of LSP-AF after PVI and linear ablation is associated with a higher number of minor complications and more time-consuming procedures. After 12 months of follow-up no additional effect was observed for defragmentation therapy regarding freedom of AF. Therefore, the use of additional defragmentation for LSP-AF compromises procedural efficiency without improving efficacy.

Freedom of atrial fibrillation

Achieving satisfactory success rates for ablation of LSP-AF is very challenging. As demonstrated by Brooks et al. [4], a great variety of techniques remain available for the ablation of LSP-AF, including: PVI, pulmonary vein antrum isolation (PVAI) and different kinds of combinations of these treatments with ablation lines and defragmentation or CFAE ablation. Several other studies have evaluated the effect of the implementation of CFAE ablation for LSP-AF [14, 20, 21]. The single-procedure, drug-free success rates from CFAE ablation alone range from 24 % to 33 % at approximately 1 year. However, no previous study has been performed on the use of subsequential PVI, linear ablation and defragmentation for LSP-AF and therefore makes it difficult to compare our results with previous findings.

Our study suggests that 56.2 % of the patients who had defragmentation are in sinus rhythm after 12 months of follow-up. However, most patients in the defragmentation and non-defragmentation group were on antiarrhythmic drugs during this period. Nevertheless, these patients suffered from severe drug-refractory AF prior to the ablation procedure. This may also explain the incremental increase in percentage of patients who were in sinus rhythm at 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively, after defragmentation therapy. In patients who underwent PVI and linear ablation without additional defragmentation, 40 % were free from AF. Since the difference between these groups did not meet statistical significance, it can be concluded that defragmentation therapy in addition to PVI and linear ablation does not improve outcome of LSP-AF.

Reconduction

One of the largest limitations of ablation for LSP-AF is the lack of durability of the venous electrical isolation [22]. Prior studies demonstrated that the majority of patients had recovered venous conduction, which was established during the repeat procedure [14, 23, 24]. This finding can be supported by our findings that a significant number of patients who experienced recurrence had PV reconduction during EP study. Willems et al. found PV reconduction in approximately 75 % of patients after the first procedure [25]. For some patients with LSP-AF the PVs are an important trigger and durable lesions may improve outcome for these patients. Therefore, we cannot conclude that defragmentation therapy had no beneficial effect for patients with LSP-AF at all, since we are not yet able to perform ablations where durability of the PVI and linear ablations can be ensured over time. In this study a limited number of repeat procedures were performed and therefore we cannot draw conclusions about the specific cause of low success rates. Possibilities are reconduction after venous isolation, linear ablation, and insufficient defragmentation therapy. However, the single procedure success rate after 12 months is not improved by performing defragmentation in LSP-AF patients.

Amount of defragmentation

Until today, the ideal amount of defragmentation for the treatment of LSP-AF remains unknown and is highly operator dependent. Our study demonstrates that additional defragmentation after linear ablation and PVI has no favourable effect on the outcome. A possible explanation for the ineffectiveness of defragmentation could be the amount of additional application time. Our results demonstrate that patients who underwent defragmentation received a significantly higher number of RF applications (on average 65 additional lesions). However, as the mean application time tends to be higher in the defragmentation group with approximately 1000 s of RF ablation, no statistically significant difference was found regarding total RF application time. The question rises as to whether more additional defragmentation would lead to an improved outcome. In other studies evaluating the effect of defragmentation in LSP-AF patients the average amount of additional RF application time was 15–33 min with a total application time of 54–64 min [14, 26]. Our study achieved comparable results regarding ablation data with 18.5 min additional defragmentation and a total ablation time of 66 min.

Complications

Although we did not see a higher rate of major complications associated with defragmentation, as was the case in the study by Elayi and co-workers [27], we observed a higher number of minor complications. Pericarditis due to extensive ablation remains a common complication [28, 29]. Our results demonstrated that patients who experienced any complications received significantly more RF applications (almost 70 more applications). This increased number of RF applications (>200) is in some patients responsible for the occurrence of reactive pericarditis leading to mild pericardial effusion and fever. Most of the patients, however, recover spontaneously and are treated conservatively [29]. Considering these complications and the fact that mean hospital stay and more importantly freedom of AF did not differ significantly according to our data could suggest that a certain restraint regarding the use of defragmentation may be indicated.

Clinical impact

From the findings of this study, the question arises whether additional defragmentation may not be beneficial for all LSP-AF patients and should not be performed routinely, but for selected patients who did not benefit from PVI and linear ablation. In these individual patients the risk of persisting AF should be balanced against the risk associated with the procedure. However, as previously stated by Tilz et al. [30], our study suggests that the additional risk of complication is not justifiable for an initial treatment with defragmentation.

When looking at the longer procedure times associated with defragmentation in our study (with a mean difference of almost 2 hours), one can conclude that ablation procedures could be much more efficient without this additional treatment and therefore less burdensome. This supports the findings concluded by Tilz et al. [30] This might also influence the cost-efficacy of LSP-AF ablation procedures.

Limitations

In this study a limited number of patients were included and analysed. However, despite this limited number of patients the absence of significant differences between the characteristics suggests homogeneity between the two groups and contributes to the validity of the conclusions drawn from these results. Furthermore, patient characteristics from our study population were in line with those from other studies [4, 14, 27]. To really elucidate the effect of additional defragmentation in addition to conventional PVI and linear ablation randomised trials with a higher number of patients are necessary.

An important issue regarding follow-up which was raised by Tilz et al. [30] remains whether observed AF recurrence rates merely depend on the length of follow-up. Like most studies about LSP-AF ablation, our follow-up lasted for 1 year and therefore does not offer further insight into this matter [14, 27]. However, longer follow-up would provide more detailed information on the treatment effect and the outcomes in the long term. In this study, patients were being treated with an antiarrhythmic drug during follow-up. Although the use of these drugs was comparable between the two groups, it might have influenced the outcomes during follow-up.

Conclusion

The lack of difference in freedom of AF and mean hospital stay between the two groups and the higher occurrence of minor complications in the defragmentation group suggests there is no strong ground to deliver complete defragmentation therapy in addition to PVI and linear ablation for patients suffering from LSP-AF.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Terasawa T, Balk EM, Chung M, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(3):191–202. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi A. Catheter ablation is established as a treatment option for atrial fibrillation–is catheter ablation established as a treatment option of atrial fibrillation? (Pro) Circ J. 2010;74(9):1972–1977. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang F, Tilz R, Chun J, et al. Long-term results of catheter ablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: lessons from a 5-year follow-up. Circulation. 2010;122(23):2368–2377. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.946806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks AG, Stiles MK, Laborderie J, et al. Outcomes of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation ablation: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(6):835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma A, Marrouche NF, Natale A. Pulmonary vein antrum isolation: intracardiac echocardiography-guided technique. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15(11):1335–1340. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.04428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhargava M, Di Biase L, Mohanty P, et al. Impact of type of atrial fibrillation and repeat catheter ablation on long-term freedom from atrial fibrillation: results from a multicenter study. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(10):1403–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calkins H, Reynolds MR, Spector P, et al. Treatment of atrial fibrillation with antiarrhythmic drugs or radiofrequency ablation: two systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(4):349–361. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.824789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Belle YL, Janse PA, de Groot NM, et al. Adenosine testing after cryoballoon pulmonary vein isolation improves long-term clinical outcome. Neth Heart J. 2012;20(11):447–455. doi: 10.1007/s12471-012-0319-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim TW, Jassal IS, Ross DL, et al. Medium-term efficacy of segmental ostial pulmonary vein isolation for the treatment of permanent and persistent atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29(4):374–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada T, Murakami Y, Okada T, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide level after radiofrequency catheter ablation of paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2007;9(9):770–774. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanagaratnam L, Tomassoni G, Schweikert R, et al. Empirical pulmonary vein isolation in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation using a three-dimensional nonfluoroscopic mapping system: long-term follow-up. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24(12):1774–1779. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letsas KP, Efremidis M, Charalampous C, et al. Current ablation strategies for persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:376969. doi: 10.4061/2011/376969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremen V, Lhotska L, Macas M, et al. A new approach to automated assessment of fractionation of endocardial electrograms during atrial fibrillation. Physiol Meas. 2008;29(12):1371–1381. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/29/12/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oral H, Chugh A, Yoshida K, et al. A randomized assessment of the incremental role of ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms after antral pulmonary vein isolation for long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(9):782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knecht S, Hocini M, Wright M, et al. Left atrial linear lesions are required for successful treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(19):2359–2366. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estner HL, Hessling G, Biegler R, et al. Complex fractionated atrial electrogram or linear ablation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation–a prospective randomized study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34(8):939–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Asinger RW, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) Developed in Collaboration With the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 2001;104(17):2118–2150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham P, Abkenari LD, Peters EC, et al. Feasibility of remote magnetic navigation for epicardial ablation. Neth Heart J. 2013;21:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s12471-013-0431-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roudijk RW, Gujic M, Suman-Horduna I, et al. Catheter ablation in children and young adults: is there an additional benefit from remote magnetic navigation? Neth Heart J. 2013;21(6):296–303. doi: 10.1007/s12471-013-0408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oral H, Chugh A, Good E, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of chronic atrial fibrillation guided by complex electrograms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2606–2612. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nademanee K, McKenzie J, Kosar E, et al. A new approach for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: mapping of the electrophysiologic substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(11):2044–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkhardt JD, Di Biase L, Natale A. Long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation: the metastatic cancer of electrophysiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(19):1930–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pratola C, Baldo E, Notarstefano P, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation: is the persistence of all intraprocedural targets necessary for long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm? Circulation. 2008;117(2):136–143. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheema A, Dong J, Dalal D, et al. Circumferential ablation with pulmonary vein isolation in permanent atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(10):1425–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willems S, Steven D, Servatius H, et al. Persistence of pulmonary vein isolation after robotic remote-navigated ablation for atrial fibrillation and its relation to clinical outcome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21(10):1079–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter M, Spear W, Akar JG, et al. Prospective study of atrial fibrillation termination during ablation guided by automated detection of fractionated electrograms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(6):613–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elayi CS, Verma A, Di Biase L, et al. Ablation for longstanding permanent atrial fibrillation: results from a randomized study comparing three different strategies. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(12):1658–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen SW, Liu SW, Lin JX. Incidence, risk factors and management of pericardial effusion post radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillations. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2008;36(9):801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertaglia E, Zoppo F, Tondo C, et al. Early complications of pulmonary vein catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a multicenter prospective registry on procedural safety. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(10):1265–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilz RR, Chun KR, Schmidt B, et al. Catheter ablation of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation: a lesson from circumferential pulmonary vein isolation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21(10):1085–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]