Abstract

Aims

The aims of this paper are to examine the relationship between psychological trauma symptoms and Type 2 diabetes prevalence, glucose control, and treatment modality among 3,776 American Indians in Phase V of the Strong Heart Family Study.

Methods

This cross-sectional analysis measured psychological trauma symptoms using the National Anxiety Disorder Screening Day instrument, diabetes by American Diabetes Association criteria, and treatment modality by four categories: no medication, oral medication only, insulin only, or both oral medication and insulin. We used binary logistic regression to evaluate the association between psychological trauma symptoms and diabetes prevalence. We used ordinary least squares regression to evaluate the association between psychological trauma symptoms and glucose control. We used binary logistic regression to model the association of psychological trauma symptoms with treatment modality.

Results

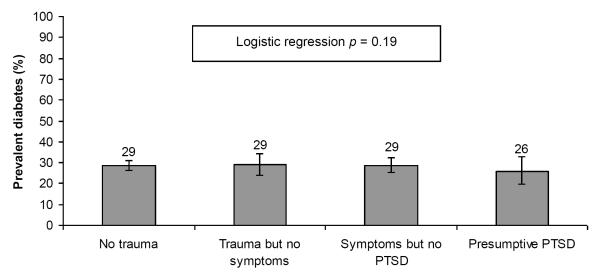

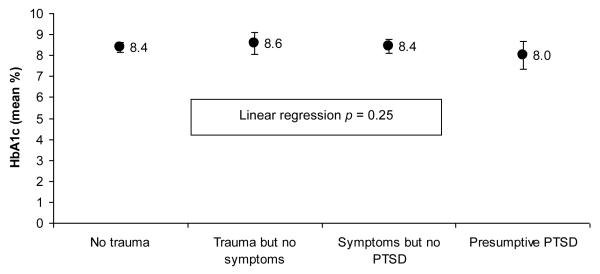

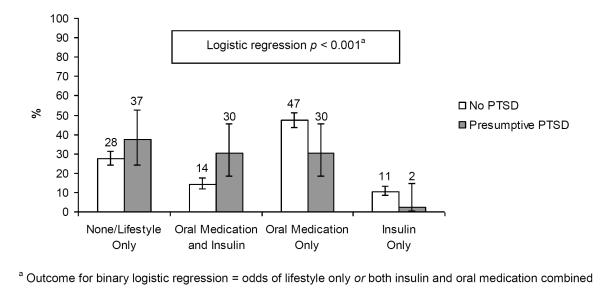

Neither diabetes prevalence (22-31%; p = 0.19) nor control (8.0-8.6; p = 0.25) varied significantly by psychological trauma symptoms categories. However, diabetes treatment modality was associated with psychological trauma symptoms categories, as people with greater burden used either no medication, or both oral and insulin medications (odds ratio = 3.1, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The positive relationship between treatment modality and psychological trauma symptoms suggests future research investigate patient and provider treatment decision making.

Keywords: diabetes treatment modality, American Indians, psychological trauma symptoms

Introduction

American Indians have disproportionately high rates of diabetes compared to other populations in the United States (Calhoun, Beals, Carter, Mete, Welty, Fabsitz, Lee, and Howard 2009; Jiang, Beals, Whitesell, Roubideaux, and Manson 2007; O’Connell, Yi, Wilson, Manson, and Acton 2010; Wang, Shara, Calhoun, Umans, Lee, and Howard 2010). American Indians also experience high levels of stress, and there is a growing concern regarding the relationship between stress burden and diabetes among American Indians (Jiang, Beals, Whitesell, Roubideaux, and Manson 2008). Understanding the causes and consequences of diabetes among American Indians is important because of the heavy burden that this disease has among that population. For example, mortality from diabetes is approximately three times higher for American Indians and Alaska Natives than for others in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007; Roubideaux 2010). People with diabetes who maintain good glucose control, however, lower their risk for mortality and long-term complications.

Recent studies have examined the possible link between psychiatric conditions and diabetes (Anderson, Freedland, Clouse, and Lustman 2001; Calhoun et al. 2009). As is common in the general literature, most of the studies among American Indians have focused on depression, generally demonstrating a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among individuals with diabetes (Jiang et al. 2007). These studies also suggest that individuals with depressive symptoms have poorer glucose control (Calhoun et al. 2009). The causes for these associations are still poorly understood, though implicated factors include insulin resistance (Lustman and Clouse 2002; Lustman and Clouse 2007); central adiposity (Everson-Rose, Meyer, Powell, Pandey, Torrens, Kravitz, Bromberger, and Matthews 2004) and diabetes-specific stressors such as negative emotions towards diabetes, adherence to recommended diabetes treatment, dietary concerns, and lower levels of social support (van Bastelaar, Pouwer, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn, Tack, Bazelmans, Beekman, Heine, and Snoek 2010).

Relatively little is known about the relationship between diabetes and other psychiatric conditions. Prevalent diabetes has been linked to elevated rates of mood and anxiety disorders (Lin, Korff, Alonso, Angermeyer, Anthony, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Gasquet, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Karam, Lara, Lee, Levinson, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Scott, Watanabe, and Williams 2008) and schizophrenia (Lin and Shuldiner 2010), but links with specific psychiatric conditions, such as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), are still being investigated. One prospective cohort study of military service members found that PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with future risk of diabetes (Boyko, Jacobson, Smith, Ryan, Hooper, Amoroso, Gackstetter, Barrett-Connor, and Smith 2010) and researchers have postulated a link between trauma and resulting stress disorders with diabetes prevalence and glucose control (Boyko et al. 2010; Dedert, Calhoun, Watkins, Sherwood, and Beckham 2010; Goodwin and Davidson 2005; Jiang et al. 2007).

Research is generally lacking in the association of PTSD symptoms with prevalent diabetes, glucose control, and diabetes treatment modality. No study examines patterns of care among people with diabetes suffering with psychological trauma. Examining treatment modality is important because of its association with severity of diabetes, differences in cost effectiveness, and patient education (Clar, Barnard, Cummins, Royle, and Waugh 2010; Delahanty, Grant, Wittenberg, Bosch, Wexler, Cagliero, and Meigs 2007). These questions are especially relevant for American Indian populations because they are disproportionately affected by PTSD, with prevalence estimates as high as 15% in some portions of the population (Beals, Manson, Whitesell, Spicer, Novins, and Mitchell 2005; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007).

We used data from the Phase V of the Strong Heart Family Study (SHS) to examine the association of psychological trauma symptoms with diabetes prevalence, glucose control, and treatment modality. The SHS is a large longitudinal effort to assess cardiovascular disease in three distinct American Indian populations, and Phase V of the SHS included a brief instrument to assess PTSD symptoms, but did not yield a clinical diagnosis, so we refer to psychological trauma symptoms, rather than PTSD here. Our specific aims were to determine whether: 1) psychological trauma symptoms correlated with higher prevalence of diagnosed diabetes; 2) psychological trauma symptoms correlated with poorer glucose control among those with diabetes; and 3) diabetes treatment modalities differed according to psychological trauma burden among those with diabetes.

Subjects

The SHS is the largest epidemiologic study of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors ever undertaken among American Indian men and women. A detailed discussion of study methods is published elsewhere (Lee, Welty, Fabsitz, Cowan, Le, Oopik, Cucchiara, Savage, and Howard 1990; Welty, Lee, Yeh, Cowan, Go, Fabsitz, Le, Oopik, Robbins, and Howard 1995). The SHS includes 13 American Indian tribes and communities in three geographic regions: Northern Plains--North and South Dakota (Oglala Sioux, Cheyenne River Sioux, and Spirit Lake Communities), Oklahoma (Apache, Caddo, Comanche, Delaware, Fort Sill Apache, Kiowa, and Wichita), and the Southwest—Arizona (Gila River and Salt River Pima/Maricopa, and Akchin Pima/Papago), and has collected a wealth of information on cardiovascular risk factors. All participants in SHS provided written informed consent and clinical assessment that included laboratory testing for cardiovascular disease. Phase V examined cardiovascular disease risk factors, diabetes-associated risk factors among 3,776 American Indian family members who were examined in 2006-2007.

Materials and Methods

Assessment of psychological trauma symptoms

Psychological trauma symptoms were measured using the National Anxiety Disorder Screening Day instrument (Marshall, Olfson, Hellman, Blanco, Guardino, and Struening 2001), which was originally developed to identify potential cases of anxiety disorder; it has been validated among American Indians in a cross-cultural study (Ritsher, Struening, Hellman, and Guardino 2002). This brief instrument, administered by interview, asks participants whether they have ever experienced any of a list of significant traumas (Have you ever had an extremely frightening, traumatic, or horrible experience like being the victim of a violent crime, seriously injured in an accident, sexually assaulted, seeing someone seriously injured or killed, or been the victim of a natural disaster?). Endorsement of a traumatic experience triggers additional questions about four symptom clusters (re-experiencing, withdrawal/loss of interest, insomnia, and avoidance) experienced in the past month. Symptom questions are based on the criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR: re-experiencing the traumatic event (Did you relive the experience through recurrent dreams, preoccupations, or flashbacks?), withdrawal/loss of interest as a result of the traumatic event (Did you seem less interested in important things, not “with it,” or unable to experience or express emotions?), insomnia as a result of the traumatic event (Did you have problems sleeping, concentrating, or have a short temper?), and avoidance of things related to the traumatic event (Did you avoid any place or anything that reminded you of the original horrible event?). Finally, participants who report experiencing psychological trauma and symptoms are asked whether any symptoms had persisted for longer than one month.

Following Marshall et al (2001), we created a 4-level summary variable reflecting the burden of self-reported psychological trauma symptoms: 1) No endorsed trauma, 2) Endorsed trauma but none of the four psychological trauma symptoms, 3) Endorsed trauma and 1-3 psychological trauma symptoms, or 4 psychological trauma symptoms but none lasting > 1 month, and 4) Endorsed trauma and all 4 psychological trauma symptoms that have lasted > 1 month. The latter category was considered to indicate presumptive PTSD because individuals meet the full screening criteria for PTSD (Marshall et al. 2001).

Assessment of diabetes

We used the SHS-derived indicator of prevalent diabetes (Calhoun et al. 2009) to classify each participant as diabetic or not diabetic at the Phase V clinical exam. The indicator was based on the American Diabetes Association criteria and primarily reflected fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, taking insulin or oral hypoglycemic medication, and/or previously diagnosed diabetes.

For diabetic participants with fasting blood glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL at the clinical exam, glucose control was measured as the total percent glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c). HbA1c reflects a weighted average of recent blood glucose levels, with higher levels reflecting higher average glucose values. For diabetic participants, elevated HbA1c is indicative of poor glucose control, and the high-normal HbA1c threshold for non-diabetic people is approximately 6%.

For each participant with diabetes, treatment modality was divided into four categories: no medication, oral medication only, injected insulin only, or both oral medication and injected insulin.

Covariates

Demographic covariates included SHS region (Northern Plains, Oklahoma, Southwest), age in years, sex, and education level (total years). We controlled for health behavior covariates known to effect blood sugar levels, including current alcohol use (during the past month: yes, no), and cigarette use (current, former, never). Body mass index was calculated as clinically measured weight in kilograms divided by the square of clinically measured height in meters (kg/m2). We also controlled for depressive symptoms, to disentangle the effects of depression versus trauma. Depression symptom score was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale (Radloff 1977). Scores ranged from 0-60, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated descriptive statistics for individuals with and without prevalent diabetes, using means with standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Cases with missing data were excluded from analysis.

To examine the relationship of psychological trauma symptoms with diabetes we calculated diabetes prevalence for participants in each psychological trauma symptom category, and used binary logistic regression to evaluate the association between psychological trauma symptoms and the odds of diabetes. Psychological trauma symptoms were modeled as a four level ordinal variable ranging from no trauma (1) to presumptive PTSD (4). We examined the unadjusted association and also fit a model adjusting for region, age, sex, education, alcohol consumption, smoking status, body mass index and depression symptoms.

To examine the association of psychological trauma symptoms with glucose control, we calculated mean HbA1c for participants in each of the 4 psychological trauma categories. We then used ordinary least squares regression to evaluate the association between psychological trauma symptoms and the mean HbA1c value for those groups. We also examined this association after adjusting for region, age, sex, education, alcohol consumption, smoking status, body mass index, depressive symptoms, and diabetes treatment modality.

To examine the relationship of psychological trauma symptoms with diabetes treatment modality, we restricted the sample to those with diabetes. We calculated the percent of individuals in each of the four treatment modality categories according to presumptive PTSD. In preliminary analyses we used multinomial logistic regression to model the association of psychological trauma symptoms with the multi-categorical treatment modality variable. These analyses suggested that we could collapse the 4 category treatment modality measure into a dichotomous indicator of treatment by lifestyle only or by both oral medication and insulin, with treatment by either oral medication or insulin, but not by both, as the reference group. We used binary logistic regression to model the association of psychological trauma symptoms with treatment modality.

Analyses were conducted using SPSS/Predictive Analytics SoftWare (PASW) version 18. All regression models used the robust variance estimator to account for clustering of multiple participants within family group. All inferential results are presented as point estimates with 95% confidence intervals, and we considered an alpha error rate of 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for demographic, heath behavior, and clinical measures according to diabetes status. Participants with diabetes were more likely to be from the Southwest region and more likely to be either current or former smokers, compared to people without diabetes. Participants with diabetes also had higher mean depressive symptoms scores.

Table 1.

Demographic, health behaviors, clinical measures, blood sugar and treatment modality among individuals in Strong Heart Study Family Study with and without diabetes

| Diabetic (N = 728) |

Not Diabetic (N = 1,828) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| % or Mean (SD) | % or Mean (SD) | p | |

| Demographics and Health Behaviors | |||

| SHS Region: | |||

| Northern Plains | 23% | 37% | < 0.001 |

| Oklahoma | 31% | 26% | |

| Southwest | 46% | 27% | |

| Age (years) | 52 (14) | 41 (15) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 65% | 61% | 0.07 |

| Education (years) | 12 (2) | 13 (2) | 0.08 |

| Current alcohol use | 36% | 57% | <0.001 |

| Cigarette use: | |||

| Current | 42% | 39% | <0.001 |

| Former | 30% | 25% | |

| Never | 28% | 36% | |

| Clinical measures | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 36 (9) | 33 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Depression symptom score | 14 (11) | 12 (10) | <0.001 |

| Blood sugar | |||

| Mean fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 180 (78) | 94 (11) | < 0.001 |

| A1ca (mean %) | 8.4 (2) | 5.7 (1) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes treatment modality | |||

| None/Lifestyle only | 28% | n/a | n/a |

| Oral medication | 46% | n/a | n/a |

| Insulin | 10% | n/a | n/a |

| Oral medication + insulin | 15% | n/a | n/a |

Out of 649 people with diabetes and 513 people without diabetes who had fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL

The prevalence of diabetes was very similar across all psychological trauma symptom categories (p = 0.65) ranging from a low of 26% to a high of 29% (Figure 1). There was no statistically significant association between PTSD symptoms and prevalent diabetes in the unadjusted (odds ratio = 1.0; 95% CI = 0.1, 1.1; p = 0.65) or covariate-adjusted (odds ratio = 0.9; 95% CI = 0.9, 1.0; p = 0.19) logistic regression models.

Figure 1.

Diabetes prevalence by psychological trauma symptoms category

Among 649 diabetic participants with fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL, there was no trend in mean HbA1c across psychological trauma symptom categories (Figure 2) with mean HbA1c ranging from 8.0 to 8.6. There was no statistically significant association between psychological trauma symptoms and mean HbA1c in the unadjusted (mean difference = 0.02; 95% CI = 0.0, 0.04; p = 0.14) or covariate-adjusted (mean difference = 0.01; 95% CI = −0.01, 0.04; p = 0.25) linear regression models.

Figure 2.

Mean hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) by psychological trauma symptoms category for 649 people with diabetes and fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL.

Diabetes treatment modality differed significantly between participants with and without presumptive PTSD (Figure 3). Participants with presumptive PTSD were more likely to not be receiving medication or to be receiving both oral medicine and insulin treatment combined (unadjusted odds ratio = 2.9; 95% CI = 1.5, 5.5; p = 0.003), and less likely to be using oral medication or insulin treatment alone. The differences in treatment regimen persisted after covariate adjustment (odds ratio = 3.1; 95% CI = 1.7, 5.7; p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Percent of diabetic participants with and without presumptive PTSD by diabetes treatment modality.

Discussion

Our study’s large sample size resulted in good statistical power for this important investigation of the relationship between psychological trauma symptoms and diabetes prevalence, glucose control, and treatment modality. Psychological trauma symptoms were not associated with diabetes prevalence, nor with glucose control. Indeed, HbA1c levels were remarkably consistent across psychological trauma symptom categories, suggesting that there are other factors, beyond the variables that we investigated, that impact American Indians’ ability to control their blood sugar. This finding contrasts with previous findings that suggest links between trauma and resulting stress disorders with diabetes prevalence and glucose control (Boyko et al. 2010; Dedert et al. 2010; Goodwin and Davidson 2005; Jiang et al. 2007), and those that link depressive symptoms with poorer glucose control.

We found that diabetes treatment modality varied by psychological trauma burden, as presumptive PTSD correlated with diabetes treatment modality. Among people with presumptive PTSD, two thirds used no medication to manage their diabetes. If they did use medication for diabetes treatment, people with presumptive PTSD used both insulin treatment and oral medication. This finding is previously unreported in the literature and may have important clinical implications for providers who are treating patients with diabetes, particularly those with co-morbid conditions and psychological trauma symptoms.

More research is needed to identify factors beyond health status that may be related to our finding statistically significant differences in diabetes treatment modality among those with presumptive PTSD. Recent evidence suggests that patient acceptance of diabetes treatment modalities and adherence to treatment may be influenced by patient fear, uncertainty, and the presence of mental health conditions (Ratanawongsa, Crosson, Schillinger, Karter, Saha, and Marrero 2012).The interaction between patients and providers may also be important in these relationships. For example, Garroutte and colleagues have studied the importance of cultural identity among American Indians, noting that patients have different levels of American Indian and White American cultural identity, leading to differences in health communication outcomes between patients and their healthcare providers (Garroutte, Kunovich, Jacobsen, and Goldberg 2004; Garroutte, Sarkisian, Arguelles, Goldberg, and Buchwald 2006; Garroutte, Sarkisian, Goldberg, Buchwald, and Beals 2008). Patterns related to cultural identity and health communication may influence provider recommendations for treatment, patient acceptance, and medical adherence among American Indians with psychological trauma and diabetes, but these relationships have yet to be investigated and reported in the literature.

The following limitations of this study may be considered. First, our design is cross-sectional and precludes us from inferring causality between psychological trauma symptoms and the diabetes-related measures assessed in this particular study. Additionally, our cross-sectional data does not allow us to examine diabetes incidence. Finally, our findings may not generalize to other populations, nor to American Indians who reside in locations other than where our sample was drawn.

In conclusion, our investigation revealed that having significant psychological trauma symptoms did have an association with diabetes treatment modality, with presumptive PTSD patients much more likely to manage their diabetes using no medication, or, using both oral and insulin treatments combined. This finding suggests that providers and patients address psychological trauma as part of a comprehensive diabetes screening and management approach.

Acknowledgements

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Indian Health Service. The Strong Heart Study was supported by cooperative agreement grants (Nos. U01HL-41642, U01HL-41652, and U01HL-41654) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The authors acknowledge the assistance and cooperation of the tribal leadership and community members, without whose support this study would not have been possible. We thank the Indian Health Service hospitals and clinics at each center, the directors, and their staffs. We also thank Spero Manson, Dedra Buchwald and all of our colleagues at the Native Elder Research Center for feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. Julia Silberman at the Heritage University Center for Native Health & Culture provided excellent administrative support during the revision process.

Grant support: Native Elder Research Center AG015292; Heritage University Center for Native Health & Culture Faculty Fellowship

Grant support for Strong Heart Study: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute U01HL-41642, U01HL-41652, and U01HL-41654

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michelle M. Jacob, University of San Diego & Heritage University, Department of Ethnic Studies & Center for Native Health & Culture, Maher 206, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA 92110.

Kelly L. Gonzales, Portland State University, School of Community Health, PO Box 751 - SCH Portland, OR 97207-0751.

Darren Calhoun, Phoenix Field Office-MedStar Health Research Institute 1616 E. Indian School Rd., Suite #250, Phoenix, AZ 85016-8803.

Janette Beals, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, Campus Box F800, 13055 East 17th Avenue, Aurora, Colorado 80045.

Clemma Jacobsen Muller, University of Washington, Box 359780, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1760, Seattle, WA 98101.

Jack Goldberg, University of Washington, Box 359780, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1760, Seattle, WA 98101.

Lonnie Nelson, Department of Health Services, University of Washington School of Public Health, Box 359780, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1760, Seattle, WA 98101.

Thomas K. Welty, Missouri Breaks Research, Inc., HCR 64 Box 52, Timber Lake, SD 57656.

Barbara V. Howard, MedStar Health Research Institute and Georgetown/Howard Universities, Center for Translational Science, 6525 Belcrest Ave Hyattsville MD..

References

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–78. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko EJ, Jacobson IG, Smith B, Ryan MA, Hooper TI, Amoroso PJ, Gackstetter GD, Barrett-Connor E, Smith TC. Risk of Diabetes in U.S. Military Service Members in Relation to Combat Deployment and Mental Health. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1771–1777. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Darren, Beals Janette, Carter Elizabeth A., Mete Mihriye, Welty Thomas K., Fabsitz Richard R., Lee Elisa T., Howard Barbara V. Relationship between glycemic control and depression among American Indians in the Strong Heart Study. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . In: National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States. D. o. H. a. H. Services, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Clar C, Barnard K, Cummins E, Royle P, Waugh N. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–140. doi: 10.3310/hta14120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedert EA, Calhoun PS, Watkins LL, Sherwood A, Beckham JC. Posttraumatic stress disorder, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease: a review of the evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39:61–78. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9165-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahanty LM, Grant RW, Wittenberg E, Bosch JL, Wexler DJ, Cagliero E, Meigs JB. Association of diabetes-related emotional distress with diabetes treatment in primary care patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2007;24:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson-Rose SA, Meyer PM, Powell LH, Pandey D, Torrens JI, Kravitz HM, Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. Depressive symptoms, insulin resistance, and risk of diabetes in women at midlife. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2856–62. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte EM, Kunovich RM, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J. Patient satisfaction and ethnic identity among American Indian older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:2233–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte EM, Sarkisian N, Arguelles L, Goldberg J, Buchwald D. Cultural identities and perceptions of health among health care providers and older American Indians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:111–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte EM, Sarkisian N, Goldberg J, Buchwald D, Beals J. Perceptions of medical interactions between healthcare providers and American Indian older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:546–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Davidson JR. Self-reported diabetes and posttraumatic stress disorder among adults in the community. Prev Med. 2005;40:570–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Beals J, Whitesell NR, Roubideaux Y, Manson SM. Association between diabetes and mental disorders in two American Indian reservation communities. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2228–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- — Stress burden and diabetes in two American Indian reservation communities. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:427–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz R, Cowan LD, Le NA, Oopik AJ, Cucchiara AJ, Savage PJ, Howard BV. The Strong Heart Study. A study of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:1141–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Korff MV, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Anthony J, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, Gasquet I, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam E, Lara C, Lee S, Levinson D, Ormel JH, Posada-Villa J, Scott K, Watanabe M, Williams D. Mental disorders among persons with diabetes--results from the World Mental Health Surveys. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65:571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PI, Shuldiner AR. Rethinking the genetic basis for comorbidity of schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes. Schizophr Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Treatment of depression in diabetes: impact on mood and medical outcome. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:917–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- — Depression in diabetes: the chicken or the egg? Psychosom Med. 2007;69:297–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318060cc2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RD, Olfson M, Hellman F, Blanco C, Guardino M, Struening EL. Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1467–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell J, Yi R, Wilson C, Manson SM, Acton KJ. Racial disparities in health status: a comparison of the morbidity among American Indian and U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1463–70. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ratanawongsa N, Crosson JC, Schillinger D, Karter AJ, Saha CK, Marrero DG. Getting under the skin of clinical inertia in insulin initiation: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Insulin Starts Project. Diabetes Educator. 2012;38:94–100. doi: 10.1177/0145721711432649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Struening EL, Hellman F, Guardino M. Internal validity of an anxiety disorder screening instrument across five ethnic groups. Psychiatry Res. 2002;111:199–213. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubideaux Yvette. In: Priorities for Reforming the Indian Health Service. Service IH, editor. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Tack CJ, Bazelmans E, Beekman AT, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ. Diabetes-specific emotional distress mediates the association between depressive symptoms and glycaemic control in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2010;27:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Shara NM, Calhoun D, Umans JG, Lee ET, Howard BV. Incidence rates and predictors of diabetes in those with prediabetes: the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:378–85. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welty TK, Lee ET, Yeh J, Cowan LD, Go O, Fabsitz RR, Le NA, Oopik AJ, Robbins DC, Howard BV. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among American Indians. The Strong Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:269–87. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]