Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to evaluate the clinical outcome of closed/open reduction and titanium elastic nails (TENs) in children with severely displaced proximal humeral fractures.

Methods

A retrospective study was performed on 37 children suffering from proximal humeral fracture between April 2009 and July 2012. All these patients were treated by closed or open reduction with TEN fixation. The healing process was assessed by radiographic and clinical follow-up for up to 36 months. Radiographic assessment was performed on the scheduled follow-ups to examine fracture healing, remodelling, bone growth and residual deformity. The clinical outcomes were evaluated using the Neer shoulder score and patients’ satisfaction report at the final follow-up. Complications related to the treatment were also recorded.

Results

All patients had a mean follow-up period of 24 months (12–36) after surgery. All fractures were healed, radiologically, at a median time of eight weeks (seven to ten weeks). There were no major complications related to the treatment. Two patients complained about skin irritation around the sides of the prominent distal ends of the nails. Implant removal took place at an average of 5.8 months post-operatively as an outpatient procedure. There were no observed complications in association with the removal of the hardware. At the final follow-up, the mean Neer shoulder score was 96.65 (range 83–100). Thirty patients were very satisfied with their surgical outcomes and the remaining seven were satisfied. Function of the affected arm returned to normal at the end of the follow-up period in all cases.

Conclusions

Combining closed or open reduction with TEN fixation is recommended for treating severely displaced proximal humeral fractures in children. Our data showed evidence of satisfactory outcomes with a low complication rate and a fast return to normal mobility of the affected arms.

Keywords: Proximal humerus, Fracture, Titanium elastic nail, Children, Surgery

Introduction

Proximal humeral fractures in children include both physeal and metaphyseal fractures, which account for less than 5 % of all paediatric fractures [1]. The majority of proximal humeral fractures are either undisplaced or minimally displaced (Neer-Horowitz grade I–II) and can be managed non-operatively with a satisfactory outcome [2, 3]. However, in cases of severe humeral fractures with significant bone displacement (Neer-Horowitz grade III–IV), especially in teenagers, non-operative treatment is controversial.

An important concern of surgeons while dealing with paediatric proximal humeral fractures is the growth of the bone and the resulting remodelling potential. In fact, approximately 80 % of the longitudinal growth of the humerus comes from the proximal humeral physis [4]. The concern for disruption of the bone growth and remodelling leads surgeons to choose non-operative treatment regardless of the degree of displacement, angulation, rotation or translation. However, immobilisation by a cast is lengthy, uncomfortable and hard for children to tolerate. The residual deformities after non-operative treatment, such as upper limb length discrepancy, humerus varus or humerus valgus, can lead to cosmetic problems due to the decreasing ability of remodelling in older children [5]. Therefore, some surgeons in recent years have recommended closed or open reduction and internal fixation for proximal humerus fractures in children, especially in teenagers [6, 7]. The methods of internal fracture fixation include percutaneous K-wires, staples, screws or plates [8–10]. However, complications such as pin tract infection, pin migration, osteomyelitis and loss of reduction have been reported using these modes of fracture fixation [8–11].

In the early 1980s Ligier et al. reported the first case of using titanium elastic nails (TENs) for internal fixation after the closed treatment of proximal humeral fractures [12]. Several other studies reported that the TEN technique had a lower complication rate compared to other internal fixation methods and was recommended as a safe method for treating displaced fractures of the proximal humerus in children [11, 13–15]. In our hospital, we started to use TEN for severely displaced proximal humeral fractures in children in 2009. The indications to use TEN intervention for this fracture in our institute are: (a) open fractures (Gustilo type I), (b) multi-trauma and (c) patients with severely displaced factures (Neer-Horowitz grade III–IV) and/or angulation over 45° between fragments. We carried out a retrospective review to evaluate these cases including the clinical and radiological assessments. Results from our experience are summarised and reported in this paper.

Methods

Patients

From April 2009 to July 2012, 37 children were treated with either closed or open reduction along with TENs for severely displaced proximal humeral fractures. All fractures were displaced by more than two thirds of the diameter of the humeral shaft and/or had angulation over 45° between fragments.

There were 25 boys and 12 girls with a mean age of 11.8 (seven to 15) years. The age distribution was: six patients under ten years, 23 patients between ten and 13 years and eight patients over 13 years. The most common cause was tumbling during play or sports, followed by traffic accidents. None of the fractures was pathological. There were no associated neurovascular injuries in the arms. There were three cases of open fracture (Gustilo type I) due to falls from heights and three cases caused by car accidents that were accompanied by head injuries and other long bone fractures. Among these patients, there were 23 metaphyseal fractures and 14 epiphyseal fractures (three cases of type I and 11 cases of type II according to the Salter-Harris classification).

Surgical technique

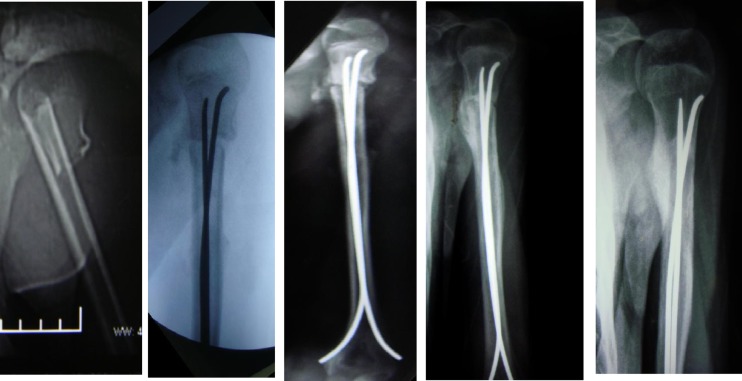

All fractures were reduced and internally fixed with TENs via the two-nail technique. All operations in the series were undertaken using a lateral and a medial supracondylar incision and two retrograde oblique drill holes were created just at the metaphyseal/diaphyseal junction. The ulnar nerve needed to be identified and protected during the procedure. Both holes were slightly larger than the diameter of the chosen nail. The diameter of the nail was determined by the diameter of the narrowest segment of the medullary canal on the X-ray. The TENs were inserted retrograde up through the medullary canal to the level of the fracture, the first through the lateral hole and the second through the medial hole. Then a closed reduction was performed, except in cases with open fractures. The closed reduction was accomplished by gentle longitudinal traction with abduction and external rotation of the arm. An image intensifier was used to monitor the reduction. Once reduction was satisfactory, the TENs were advanced across the fracture site into the proximal humeral fragment. For the metaphyseal fractures, if there was good stability, the nails were inserted into the proximal metaphysis, stopping short of the physis (Fig. 1). If not, the nails were passed across the growth plate as for the physeal fractures of the proximal humerus. The chosen TEN for these epiphyseal fractures was thinner in diameter. The nails were appropriately rotated to achieve final reduction and a satisfactory position in the proximal humerus without violating the cortex or shoulder joint.

Fig. 1.

Pre-, intra- and post-operative radiographs of the left proximal humeral metaphyseal fracture in a 14-year-old boy

If two or three closed reduction attempts failed, an open reduction was performed using a 2.5 cm long anterior delto-pectoral incision. After retracting the interposed soft tissues, fractures could be reduced successfully, and the nails were advanced across the fracture under direct vision. The two TENs were then bent distally and cut. The nails were placed at least one centimetre off the cortical surface to allow for easy removal at a later date. Surgical wounds were closed with medical tissue adhesive.

Post-operative management

The arm was kept in a cuff sling for no more than one week for pain relief. During this period, the patients were encouraged to remove the sling three times daily and perform pendulum exercises of the shoulder. From the second week onwards, patients were required to progress from active assisted to active exercises as tolerated. Radiographs were taken at four, eight and 12 weeks after surgery to confirm healing and then every six months until two years after surgery to assess remodelling, normal growth and pin-related complications.

Outcome assessment

We undertook a retrospective review to evaluate outcomes including complications related to treatment, clinical results and radiological assessments. The potential complications related to treatment include neurovascular injury, deep infection, pin tract infection, pin migration, loss of reduction and skin irritation. The evaluation of the clinical outcomes was both objective and subjective. At the final follow-up, shoulder function was assessed by the Neer shoulder score and patients were asked about their satisfaction with the surgical outcomes. Radiological evaluations were carried out using anterior, posterior and lateral views of the humerus. The radiographs were taken at the aforementioned intervals and were examined for fracture healing, angulation at the fracture site, premature closure of the growth plate and shortening of the humerus.

Results

All patients underwent surgery successfully and two TENs were used in each patient. The mean age at the time of surgery was 11.8 years (range 7–15). The average operating time was 65 minutes. The diameter of each nail for metaphyseal fractures was 3.0–4.0 mm and 2.5–3.0 mm for epiphyseal fractures. A total of 25 fractures were reduced by closed reduction, while 12 patients underwent open reduction, including three cases with open fractures and three cases with multi-trauma; in the six other patients with open reduction, in four cases it was found that the fracture site was interposed with periosteum, and in the other two cases the fracture site was interposed with the long head of the biceps.

All patients had follow-up post-operatively, and the duration ranged from 12 to 36 months with an average of 24 months. Major complications, such as deep infections, neurovascular injuries, loss of reduction and nail migration, were not observed. Skin irritation relating to protruding hardware at the distal humerus occurred in two cases, and resolved following implant removal.

The range of shoulder motion returned to normal at an average of 2.5 months post-operatively. The mean Neer shoulder score of the affected shoulder was 96.65 (range 83–100). Of the patients, 81 % (30/37) were very satisfied and 19 % (seven of 37) were satisfied; no patients reported their outcome as unsatisfactory. All patients had a full range of pain-free motion of the shoulder and returned to full sports activities.

The radiographic evidence of fracture healing occurred at a mean time of eight weeks (range seven to ten weeks) after surgery. Implant removal took place at an average of 5.8 months post-operatively as an outpatient procedure. There were no observed complications in association with the removal of the hardware. There were no instances of loss of reduction, nail migration, residual deformity or epiphyseal arrest during follow-ups.

Discussion

Results from our four-year experience of using TENs suggest that TENs are a good option for children with severely displaced proximal humeral fractures. The TEN technique is a minimally invasive operation to provide a solid fixation to the fractured bone. The advantages include the facilitation of closed fracture reduction, achievement of a better reduction by rotation of the nails, few complications and the early start of functional exercises [11–15].

In our series, closed reduction and the reduction aided by the tip of the nail resulted in an anatomical reduction in 23 cases. In the cases where two or three closed reduction attempts failed, an open reduction was performed using a 2.5 cm long anterior delto-pectoral incision. Multiple attempts are inappropriate and dangerous because they increase the risk of damaging the growth plate, especially for epiphyseal fractures. The main reasons for the failure of closed reduction were the interposition of soft tissues between the factures such as capsular or periosteal ‘buttonholing’ phenomenon and the interposition of the long head of the biceps [7, 16]. In six patients undergoing open reduction in our study, four fractures were interposed with muscle and periosteum, and the other two were interposed with the long head of the biceps.

There were not any major complications recorded in our study. In particular, we have not observed problems such as deep infection, injury to vital nerves and vessels, and perforation of the nail through the humeral head. The TEN always goes through the medullary canal, which will not damage the neurovascular structures and the end of nail is buried in the subcutaneous region, which reduces the chances of infection. Skin irritation related to protruding hardware at the distal humerus occurred in two cases and resolved following TEN removal. We accept the risk of a second operation that is invariably required to remove the hardware because of the simple procedure and lack of associated complications.

In performing a TEN procedure, some surgeons prefer the one-nail technique because it can decrease the operating time and cost and simplify both the insertion and removal procedures; however, they recommend the use of a sling for two weeks for protection of the osteosynthesis [17]. In our study, we chose the two-nail technique, which required patients to use a cuff sling for less than one week. We believe that the two-nail technique can provide greater stability compared to the one-nail method. Two nails are biomechanically superior to one nail as the divergent ends of two nails exert equal compression forces to both sides of the fracture, whereas a single nail can only apply an unopposed compression force towards the concave of its curvature, which is usually parallel to the calcar. Two TENs can also provide six points of fixation and a more stable three-dimensional anti-rotational construction compared to one nail. Greater stability allows for safe and comfortable early pendulum exercises that will facilitate the healing process of the affected arm.

A risk of injury to the ulnar nerve exists when inserting a medial TEN in the two-nail TEN technique. Ulnar nerve instability is quite often present in children and more than half subluxate their ulnar nerve when their elbow is bent more than 90° [18]. Ulnar nerve injury did not occur in our study due to our safe method: we extended the elbow while inserting the medial TEN to keep the ulnar nerve out of harm’s way.

For physeal injury of the proximal humerus, it is critical to avoid injury to the growth plate as the nails had to be passed retrograde across the growth plate into the epiphysis in order to achieve maximal stability for maintaining the anatomical reduction. To minimise injury to the growth plate, we chose two thinner TENs to maintain reduction for proximal epiphyseal fractures and some metaphyseal fractures. Although we do not have direct evidence to state that the two thinner nails will better protect the growth plate, the indirect evidence based on the two-year follow-ups showing that there were no cases of premature closure of the growth plate, humeral length discrepancy or varus/valgus angular deformities identified suggests that it was an optimal alternative for this type of facture. A similar result was reported by Fernandez et al. [14] who also conclude the two-nail TEN procedure provides better protection of the growth plate. In contrast, Chee et al. [17] reported humeral shortening of 1.5 cm after perforation of the growth plate with one larger TEN. A controlled study, which will be our future project in this line of research, is needed to draw any solid conclusions.

The results of our study demonstrate that once reduction has been achieved, by closed or open means, the two-nail TEN technique is a good choice for treating severely displaced proximal humeral fractures in children. The surgical procedure is safe with a low complication rate and provides stable fixation that can avoid the need for uncomfortable immobilisation and allow for early mobilisation of the affected shoulder.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Dr Bin Zheng, from Department of Surgery, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, who helped us with the writing and editing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bishop JY, Flatow EL. Pediatric shoulder trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432:41–48. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000156005.01503.43<. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neer CS, Horowitz BS. Fractures of the proximal humeral epiphyseal plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1965;41:24–31. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196500410-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen CF, Kiaer T, Lindequist S. Fractures of the proximal humerus in children. Nine-year follow-up of 64 unoperated on cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:255–257. doi: 10.3109/17453679008993512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pritchett JW. Growth and prediction of growth in the upper extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:520–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dameron TB, Jr, Reibel DB. Fractures involving the proximal humeral epiphyseal plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgos-Flores J, Gonzalez-Herranz P, Lopez-Mondejar JA, et al. Fractures of the proximal humeral epiphysis. Int Orthop. 1993;17:16–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00195216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahrs C, Zipplies S, Ochs BG, et al. Proximal humeral fractures in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:238–242. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31819bd9a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herscovici D, Jr, Saunders DT, Johnson MP, et al. Percutaneous fixation of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vander Have K, Herrera J, Kohen R, et al. The use of locked plating in skeletally immature patients. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:436–441. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200808000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watford KE, Jazrawi LM, Eglseder WA., Jr Percutaneous fixation of unstable proximal humeral fractures with cannulated screws. Orthopedics. 2009;32:166. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090301-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson PH, Bae DS, Waters PM. Intramedullary nailing versus percutaneous pin fixation of pediatric proximal humerus fractures: a comparison of complications and early radiographic results. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:617–622. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3182210903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ligier JN, Metaizeau JP, Prévot J. Closed flexible medullary nailing in pediatric traumatology. Chir Pediatr. 1983;24:383–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajan RA, Hawkins KJ, Metcalfe J, et al. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing for displaced proximal humeral fractures in older children. J Child Orthop. 2008;2:15–19. doi: 10.1007/s11832-007-0070-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez FF, Eberhardt O, Langendörfer M, et al. Treatment of severely displaced proximal humeral fractures in children with retrograde elastic stable intramedullary nailing. Injury. 2008;39:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie F, Wang S, Jiao Q, et al. Minimally invasive treatment for severely displaced proximal humeral fractures in children using titanium elastic nails. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:839–846. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3182306860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HG. Operative reduction of an unusual fracture of the upper epiphyseal plate of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1944;26:401–404. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chee Y, Agorastides I, Garg N, et al. Treatment of severely displaced proximal humeral fractures in children with elastic stable intramedullary nailing. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:45–50. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaltz I, Waters PM, Kasser JR. Ulnar nerve instability in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:567–569. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]