Abstract

Background

Shoulder ROM and function of the shoulder are difficult to evaluate in young children. There has been no determination of the age at which children can comply with the current assessment tools in use, but doing so would be important, because it gives us more accurate insight into the development and assessment of shoulder functional ROM in young children.

Questions/purposes

We (1) determined whether age would limit the use of two different observational scales used to assess shoulder ROM and function in young children (the Mallet scale and the ABC Loops protocol); and (2) compared the two scales in terms of intra- and interobserver reliabilities.

Methods

Sixty-five able-bodied children (32 boys, 33 girls; mean age, 3.9 years; range, 0.5–7.0 years) were recruited from local preschools and evaluated using the Mallet scale and ABC Loops protocol. Children were assessed on their ability to complete the examinations and time to completion for each measurement protocol. Intra- and interobserver reliability was tested by percentage agreement. Forty-eight children (mean age, 4.4 years; SD, 1.3 years) were able to complete the Mallet and ABC Loops measurement protocols; 17 children (mean age, 2.3 years; SD, 1.1 years) failed to complete either test.

Results

Younger children had more difficulty completing the examinations; there was a strong negative correlation between age and failure: probability of failure increased with decreasing age (Pearson r = −0.601, p < 0.001). Children who were able to complete one test were able to complete the other. Interobserver and intraobserver agreement was very high for both scales (in excess of 95% for all comparisons), and with the numbers available, there were no differences between the scales.

Conclusions

The Mallet scale and ABC Loops protocol have high reliability metrics in children younger than 6 years, but very young children (those younger than 3 years) generally will not be able to complete the examinations. The ABC Loops test took longer to perform than the Mallet scale but may more comprehensively evaluate a child’s functional capabilities. We therefore state that both assessment tools can be reliably used in children older than 3 years; we believe the ABC Loops gives a more accurate assessment of shoulder ROM.

Introduction

Active ROM and function of the shoulder are difficult to assess in young children for many reasons, including their inability to understand verbal and gestural commands, limited attention span, underdeveloped neuromuscular control, and fear of the examination process [9, 10]. Conditions such as brachial plexus birth palsy bring children to medical attention soon after birth and often necessitate treatment, surgical and otherwise, based on an assessment of impaired shoulder function [4, 5, 11]. Evaluating shoulder function and measuring the effectiveness of any given treatment in this population are inescapably compromised by the limitations in reliably performing an accurate assessment of motor function.

In patients with brachial plexus birth palsy, the Mallet scale [6] commonly is performed [7, 13, 15] and has been offered as a reliable tool to make relevant observations of shoulder motion and function [1, 14]. The Mallet score is an active motion scale that evaluates five discrete upper extremity positions. Each position is graded on a I through V scale. Because these positions and their severity are snapshots of a function and discretely enumerated, the scale lacks sensitivity because it misses steps between each position. These positions are also biased toward functions of external rotation and achievement of them is severely compromised by an internal rotation contracture. Therefore, any treatment to alter external rotation will be heavily favored by the Mallet score, yet it will not measure other problems the intervention may have neglected or made worse. In addition, the positions of the Mallet score do not assess cross-body motion or functions.

There is some support for use of this scale in that one study demonstrated acceptable intra- and interobserver reliability (mean kappa value, 0.76 and 0.78, respectively), at least in terms of different examiners in the same institution measuring the same patient [1]. However, no data confirm that this scale comprehensively reflects shoulder function, and it is not clear at what age a patient may reasonably be able to cooperate with testing to be measured by this scale, which assesses active motion. In this study, we introduce a new assessment protocol to measure shoulder ROM: ABC Loops. This assessment protocol is essentially created as a fluid, natural shoulder movement measurement instrument that would be more inclusive and sensitive so as to more accurately guide clinical decision-making and be an effective outcomes analysis tool.

We (1) determined whether age may limit the use of two different observational scales used to assess shoulder ROM and function in young children (the Mallet scale and the ABC Loops protocol); and (2) compared the two scales in terms of intra- and interobserver reliabilities.

Subjects and Methods

We performed a prospective cross-sectional analysis on 65 able-bodied children, 32 boys and 33 girls, with an average age of 3.9 years (range, 0.5–7.0 years) recruited from among preschool and day care centers in the Los Angeles metropolitan area (Table 1). Children recruited for this study were children between 0 and 7 years old. We did not approach children for possible inclusion who were physically or mentally impaired. All 65 children had full active and passive ROM without limitation or physical impairment. Institutional review board approval was obtained for all aspects of this study. Parents gave written informed consent for participation of their children in this study.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Age of subjects (years) | Number of subjects | Male/female (number of subjects) | Age (years)* | Number of subjects completing the Mallet scale | Number of subjects completing ABC Loops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0/1 | 0.45 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 7 | 5/2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 15 | 7/8 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 8 | 8 |

| 3 | 12 | 6/6 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 11 | 11 |

| 4 | 13 | 6/7 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 11 | 11 |

| 5 | 12 | 5/7 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 12 | 12 |

| 6 | 5 | 3/2 | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 65 | 32/33 | 3.87 ± 1.54 | 48 | 48 |

* Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Shoulder and elbow ROM were assessed to preclude the possibility of physical impairment [12]. Four high-definition video cameras were positioned to provide front, back, and two side views to the examination. The Mallet scale and ABC Loops protocol were evaluated in all children to the extent possible. The examinations were timed and the time recorded. A 15-minute limit was preestablished as the termination point for studies of children having difficulty participating. For the testing trials that were incomplete, the reason for failure was identified as one or more of the following: anxiety, attention deficit, insufficient motor skills, other emotional response, and/or comprehension failure.

The Mallet and ABC Loops examinations were performed by the same two research staff members (FvdB, MP) in the same way each time, starting with the Mallet scale. The examiner first verbally described the intended motion and demonstrated the movement for the child. In a playful way, we would have the child repeat the movement after the examiner demonstrated it. If this was nonproductive, the examiner next tried to compel the movement by strategically positioning desirable objects such as toys, cell phones, and keys. For example, playful stickers were applied to the children’s body on the desired target to motivate them to reach the intended position. Finally, if necessary, the examiner moved the children’s arms to the desired position, showing them what to do, and then asked them to repeat the same movement. If the child did not complete the movements after these efforts, that part of the examination was labeled as failure. Passive and active ROM of the shoulder and elbow was evaluated afterward.

Multiple authors have described the Mallet scale [1, 10, 14] and its suggested modifications. The five studied shoulder movements were graded on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being no movement and 5 being completely full and normal movement (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

We used the convention of the modified Mallet scale so Grades I and V (not shown) correspond to “no function” and “normal function,” respectively. (Redrawn and modified from the original in Mallet [6])

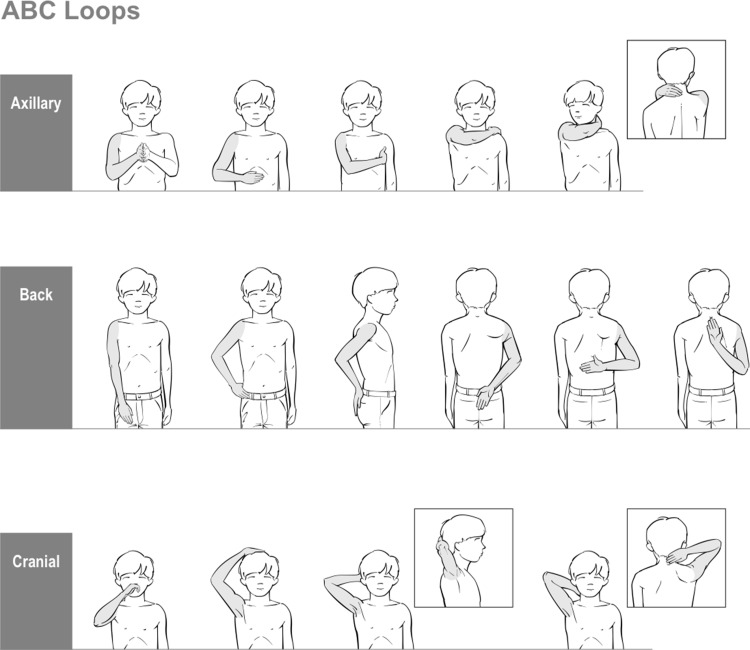

ABC Loops consists of an axillary loop (A), a back loop (B), and a cranial loop (C) (Fig. 2). This assessment protocol is based on the concept of motion loops in which the subject reaches a series of functionally relevant positions requiring increasingly greater ROM. Each subsequent position along a functional loop requires an increase in shoulder elevation, anterior or posterior, adduction, and/or rotation. In addition to grading the ability to complete the entire loop, movement quality is assessed. For children with impairment, each individual position in each of the loops is graded as “able,” “unable,” or “able with compensation.” The last of these refers to when the child can reach the target with some compensatory movement such as moving the target to the hand (eg, tipping the head slightly so as to reach the back of the head, in the cranial loop).

Fig. 2.

The ABC Loops protocol consists of three functional arcs of motion named for their general trajectory: A = axillary loop, B = back loop, and C = cranial loop. Each picture represents one position in a “Loop”; each subsequent position requires greater ROM.

Statistical Analysis

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r) was used to measure the correlation between the age of the subjects and the time it took to complete a protocol and to measure the correlation between age and failure. The independent-sample t-test was used to analyze whether there was a significant difference in age between the failure and nonfailure groups. The subjects were divided by age group: 0 to 2 years, 2.1 to 3 years, 3.1 to 4 years, 4.1 to 5 years, and 5.1 to 7.0 years. A one-way ANOVA test was performed to determine whether there was a significant difference in the risk of failure between the age groups. The Tukey multiple comparison test was used to identify the significant differences for risk of failure among the tested groups.

Intra- and interobserver reliability was assessed for four independent observers, two orthopaedic surgeons (MLP, NL-M), one occupational therapist (JL), and one physical therapist (SR), reviewing the video examination of 10 representative children, two from each of ages 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 years. All of these 10 children were able to complete the Mallet and ABC Loops protocols. The video examinations were split-screen videos showing simultaneous front, back, and side projections of the entire examination (Fig. 3). Interobserver agreement between reviewers was defined as 100% if there was no difference between their scores and 0% if the difference was the maximum possible; intermediate agreements were linearly interpolated from the relative differences. The average agreement was the average of the agreement over all pairs of reviewers over all subjects. Intraobserver agreement was defined analogously except that the scores from the same reviewer were compared between two review sessions, which were separated by at least 8 weeks. The SPSS® software package (Version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Fig. 3.

A split-screen video screen shot shows a subject performing a test in front, back, and side views.

Results

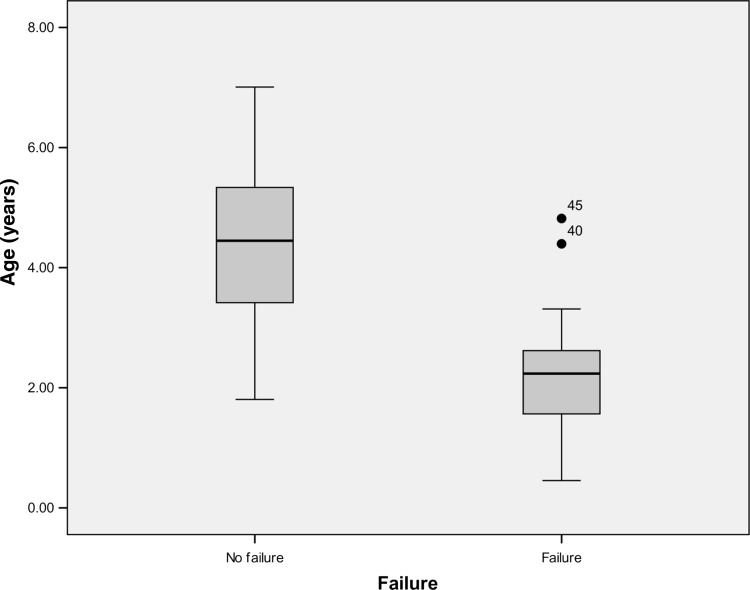

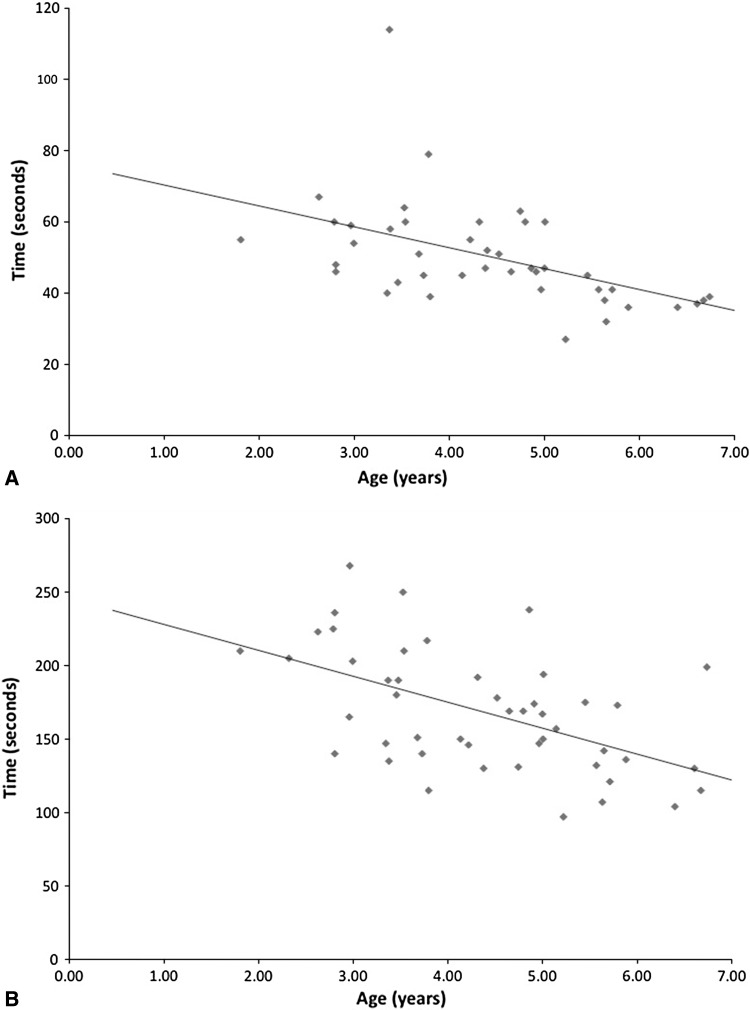

Younger patients were less likely to be able to complete either the Mallet scale or the ABC Loops protocol. The Pearson correlation coefficient showed a strong negative correlation between age and failure to complete either examination. With decreasing age, the probability of failure increased; this applied to both assessment protocols (r = −0.601, p < 0.001). The independent-sample t-test showed a significant age difference between the failure group (mean, 2.3 years; SD, 1.1 years) and the nonfailure group (mean, 4.4 years; SD, 1.3 years) (T[63] = 5.972, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Reasons for failure were age-dependent and were observed as one or more of the following: anxiety, inability to comprehend instructions, attention deficit, and insufficient motor control (Table 2). The Tukey multicomparison test showed a significant difference for risk of failure between the youngest group (0–2 years) and the groups starting from age 3.1 years and older (Table 3). The mean time to completion was 51 seconds for the Mallet scale and 168 seconds for the ABC Loops protocol. The ABC Loops measures each arm individually, whereas in the Mallet scale, both arms are evaluated simultaneously. The Pearson correlation test showed a strong, highly significant, negative correlation between the age of the subjects and the time to complete both the Mallet scale (r = −0.535, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5A) and the ABC Loops protocol (r = −0.613, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Box plots show age distribution (mean and 1 SD) of the failure and nonfailure groups. Two 4-year-old subjects who were uncooperative and failed to complete the assessment were outliers (isolated dots). The failure group was younger than the nonfailure group.

Table 2.

Reasons for failure by age

| Age of subjects (years) | Number of subjects | Number of subjects completing the Mallet scale | Number of subjects completing ABC Loops | Main reasons for failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | (1) Comprehension failure |

| 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | (1) Anxiety (2) Comprehension failure (3) Attention deficit (4) Insufficient motor skills |

| 2 | 15 | 8 | 8 | (1) Comprehension failure (2) Insufficient motor skills (3) Anxiety |

| > 3 | 42 | 39 | 39 | (1) Anxiety |

Table 3.

Results of the Tukey multicomparison test

| Age group | Compared age groups | Mean difference | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 years | 2.1–3 years | 0.408 | 0.155 | 0.076 |

| 3.1–4 years | 0.792 | 0.161 | < 0.001 | |

| 4.1–5 years | 0.732 | 0.157 | < 0.001 | |

| 5.1–7.0 years | 0.875 | 0.157 | < 0.001 |

Significant differences were found between age group 0–2 years old and all other age groups except for 2.1–3 years old.

Fig. 5A–B.

Scatterplots with linear trend lines plot subject age against the time to complete (A) the Mallet scale and (B) the ABC Loops protocol. Pearson correlation analysis showed correlations between subject age and time to complete the Mallet scale (r = −0.535, p < 0.001) and the ABC Loops protocol (r = −0.613, p < 0.001).

Interobserver average agreement between reviewers was 96% for ABC Loops and 95% for the Mallet scale. Intraobserver average agreement was 98% for ABC Loops and 97% for the Mallet scale. With the numbers available, there were no differences in these reliability statistics between tests. For this set of children, all the variation in the Mallet scale was the result of the hand-to-mouth assessment, or presence of a “trumpet sign,” generally at approximately 75% agreement. There was no single aspect of the ABC Loops protocol that showed greater variation than any other.

Discussion

Assessment of the neuromuscular capabilities and active function of the shoulder in a young child is challenging, and the closer to infancy, the greater the challenge. Brachial plexus birth palsy epitomizes the importance of an accurate shoulder examination in the very young child, because it requires careful assessments from birth onward with profound implications for the various treatments under consideration [10]. Several scoring systems have been advocated to grapple with these concerns [3, 6, 8]. However, there is little evidence to guide clinicians and researchers on the topic of when a patient is old enough to cooperate with these evaluation tools, and, to our knowledge, only one study has evaluated intra- and interobserver reliability of the most commonly applied evaluation protocol, the Mallet scale [1]. We therefore sought to determine whether age may limit the use of two different observational scales used to assess shoulder ROM and function in young children (the Mallet scale and the ABC Loops protocol) and compared the two scales in terms of intra- and interobserver reliabilities. To do this, we evaluated a normal population in an ideal environment to better guide clinical efforts when the circumstances are less opportune, and we used the Mallet scale [6] along with one only in use at our institutions, ABC Loops.

A limitation of this study is that the current study included only able-bodied children. The feasibility and reliability of the Mallet and ABC Loops tests may differ in children with disabilities who may show greater variation in ability to perform the two assessments. In addition, because most children could perform all functions compromised the ability for discriminating between observers in the reliability analysis. Evaluating reliability from videotapes may represent another limitation possibly allowing raters more time to determine ratings as compared with a live clinical setting. Videotaped examinations, however, do ensure that the examiners are seeing the same examination unlike repeated clinical examinations at different times by different examiners. Reviewers did not identify any limitations associated with the videotape format. In fact, several reviewers reported that seeing the child from front, back, and side angles at the same time was a tremendous benefit for seeing subtle differences. It could be argued that by performing the Mallet score first, children were more informed in how to participate in an active ROM examination, biasing the study in favor of the Loops. However, our data show that children successful in completing both examinations did so in much less time than was allotted. This suggests that it was factors other than the opportunity to learn from the Mallet score.

ABC Loops also proved to be limited by the reliability of young children to complete any active motor examination. In addition, all existing tools that assess motor function in young children do not easily help a clinician distinguish between active and passive ROM differences. Whether the lack of external rotation is a motor problem or a contracture is not measured, yet it most often determines the treatment indicated. This raises the possibility of expanding the ABC Loops in future studies to include a passive component where the examiner positions the arm in a desired position and records it separately. We did not evaluate the Active Movement Scale [3]; this assessment protocol has been useful in the neonate under consideration for brachial plexus exploration and grafting [2, 3]. The Active Movement Scale, however, grades motion by the amount of active motion achieved within a child’s passive range. Its greatest and only application, therefore, is for the infant, who is too young to have had joint contractures develop.

Our data suggest that most children older than 3 years can and will complete the Mallet and the ABC Loops protocols. Children younger than 2 years were often anxious toward the research staff and did not cooperate. Children between 2 and 3 years old were more cooperative but often lacked the motor skills to perform all of the movements. Especially problematic were the B loop in the ABC Loops protocol and the hand-on-spine position in the Mallet scale (reaching behind the back). In the failure group, there were two subjects who stood out because of their age (older than 4 years). These children had the cognitive and motor skills to successfully complete the protocols; however, they were very shy and would not work with us. Reasons for failure in the other subjects varied but were all expected considering the age of the subjects. One can extrapolate that the failure rate may increase in the clinical setting. Successful examinations were all completed in less than 5 minutes. In the context of our study, the examination either worked or did not. Both assessment systems fared equally well in that when one could be performed, so could the other.

The Mallet score is quick and efficient and has demonstrated fair to excellent test-retest reliability varying from 37% [14] to 90% [10]. Our intra- and interobserver reliability analysis indicates that in healthy children, there is no difference here between both protocols. Studies are underway to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of ABC Loops and its ability to identify children with shoulder-related disabilities. Obtaining pre- and postoperative scores will also be helpful in outcomes analysis [16]. Motion analysis studies are underway to quantify the extent that each stopping point in a loop requires an increase in shoulder elevation and/or plane and/or rotation.

In this study, there was no difference in children’s abilities to complete the Mallet scale and ABC Loops. The ABC Loops protocol takes longer than the Mallet scale but more comprehensively reflects the child’s functional capabilities. Furthermore, there is sufficient overlap between the scales that, with a slight modification of the C loop hand-to-mouth position, one can derive a Mallet score from an ABC Loops examination. Both assessment tools can be reliably used in children older than 3 years. We recommend recording passive and active ROM as best as possible in younger children to the limits possible in a clinical setting. Unfortunately, for many children younger than 3 years and nearly all children younger than 2 years, many of whom will receive surgical treatment or at least be considered for such, there remains no standardized assessment tool that can be equally applied before and after their intervention.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Bae DS, Waters PM, Zurakowski D. Reliability of three classification systems measuring active motion in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1733–1738. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bialocerkowski AE, Galea M. Comparison of visual and objective quantification of elbow and shoulder movement in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2006;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1749-7221-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis C, Stephens D, Clarke HM, Andrews D. The active movement scale: an evaluative tool for infants with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:470–478. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.32965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoeksma AF, Wolf H, Oei SL. Obstetrical brachial plexus injuries: incidence, natural course and shoulder contracture. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14:523–526. doi: 10.1191/0269215500cr341oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kon DS, Darakjian AB, Pearl ML, Kosco AE. Glenohumeral deformity in children with internal rotation contractures secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy: intraoperative arthrographic classification. Radiology. 2004;231:791–795. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313021057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallet J. [Obstetrical paralysis of the brachial plexus. 3. Conclusions] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1972;58:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehlman CT, DeVoe WB, Lippert WC, Michaud LJ, Allgier AJ, Foad SL. Arthroscopically assisted Sever-L’Episcopo procedure improves clinical and radiographic outcomes in neonatal brachial plexus palsy patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:341–351. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31820cada8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelow BJ, Clarke HM, Curtis CG, Zuker RM, Seifu Y, Andrews DF. The natural history of obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:675–681. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosqueda T, James MA, Petuskey K, Bagley A, Abdala E, Rab G. Kinematic assessment of the upper extremity in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:695–699. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200411000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearl ML. Shoulder problems in children with brachial plexus birth palsy: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:242–254. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearl ML, Edgerton BW, Kazimiroff PA, Burchette RJ, Wong K. Arthroscopic release and latissimus dorsi transfer for shoulder internal rotation contractures and glenohumeral deformity secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:564–574. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards RR, Bigliani LU, Gartsman GM, Ianotti JP, Zuckerman JD. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibinski M, Hems TE, Sherlock DA. Management strategies for shoulder reconstruction in obstetric brachial plexus injury with special reference to loss of internal rotation after surgery. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2012;37:772–779. doi: 10.1177/1753193412440221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Sluijs JA, van Doorn-Loogman MH, Ritt MJ, Wuisman PI. Interobserver reliability of the Mallet score. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:324–327. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Gelein Vitringa VM, van Kooten EO, Jaspers RT, Mullender MG, van Doorn-Loogman MH, van der Sluijs JA. An MRI study on the relations between muscle atrophy, shoulder function and glenohumeral deformity in shoulders of children with obstetric brachial plexus injury. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2009;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Waters PM, Bae DS. Effect of tendon transfers and extra-articular soft-tissue balancing on glenohumeral development in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:320–325. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]