Abstract

In the Vibrio cholerae pathogen, initiation of bacterial quorum sensing pathways serves to suppress virulence. We describe herein a potent and chemically stable small molecule agonist of V. cholerae quorum sensing, which was identified through rational drug design based on the native quorum sensing signal. This novel agonist may serve as a useful lead compound for the control of virulence in V. cholerae.

Introduction

Bacterial cells communicate with one another by producing, releasing, and detecting extracellular signaling molecules called autoinducers. This signaling process, termed quorum sensing (QS), enables groups of bacteria to synchronously modulate their behavior as a function of cell-population density.1–4 Specifically, autoinducers accumulate at high cell densities, and their detection drives synchronous group-wide changes in gene expression. QS-mediated behaviors are crucial in bacterial infection; accordingly, small-molecule modulators of QS pathways represent promising lead compounds en route to novel anti-bacterial therapeutics.5–11

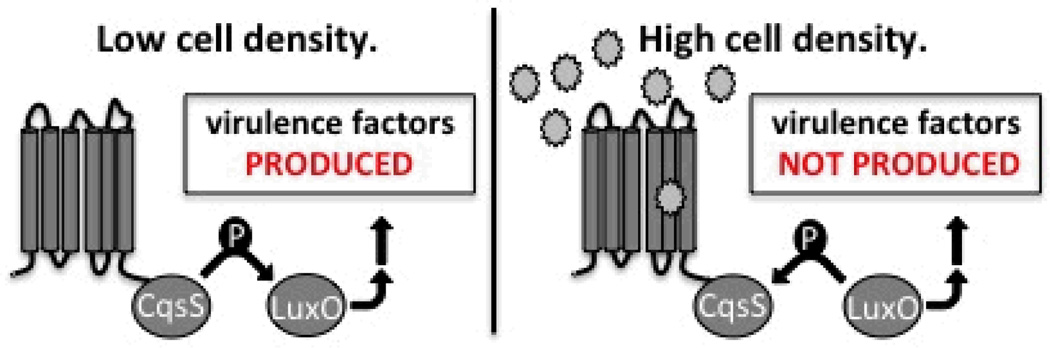

Typically, in pathogenic bacteria that cause persistent infection, the accumulation of autoinducers at high cell densities triggers QS-mediated virulence factor production and biofilm formation.12–15 By contrast, Vibrio cholerae, which causes the acute intestinal disease cholera, displays an unusual QS profile: at high population density, QS initiates a cascade that suppress virulence factor production (Figure 1).16–20 The distinct QS behavior exhibited by V. cholerae is attributed to its life cycle. Successful infection by V. cholerae leads to profuse diarrhea, which washes huge numbers of bacteria from the human intestine into the environment. Thus, at low cell density, the expression of genes for virulence and biofilm formation promotes establishment of infection in the host, while at high cell density, autoinducer-dependent repression of these traits promotes dissemination. The consequence of this QS behavioral profile is that potent small-molecule agonists of QS could conceivably be used to repress virulence in V. cholerae. The development of an effective QS agonist for V. cholerae as a therapeutic agent is anticipated to have significant global ramifications, particularly in developing regions, which are especially vulnerable to the devastating effects of this pathogen.

Figure 1.

Simplified schematic of quorum sensing in V. cholerae. In the absence of an agonist (i.e. at low cell density), CqsS acts as a kinase and virulence factors are expressed. When CqsS binds an agonist (stars), such as at high cell density with higher concentrations of the native agonist CAI-1 and Ea-CAI-1, CqsS acts as a phosphatase, repressing the expression of virulence factors.

Our strategy is to develop “pro-QS” molecules (agonists) that induce V. cholerae cells to exhibit high cell density behaviors – most notably repression of genes encoding virulence factors and those required for biofilm formation – regardless of their actual cell density. Previous work supports the feasibility of this strategy.20,21 Using an infant mouse model, we found that a V. cholerae mutant genetically locked in the high cell density state was severely defective in colonization.20 Furthermore, commensal Escherichia coli engineered to produce the V. cholerae autoinducer protected mice from V. cholerae infection, indicating that a pro-QS molecule can function as a therapeutic in vivo.21 The strategy may also be applicable to other human pathogens from the vibrio genus, such as Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus because, in these species, QS also represses virulence and biofilm traits at high cell density.18,22–27

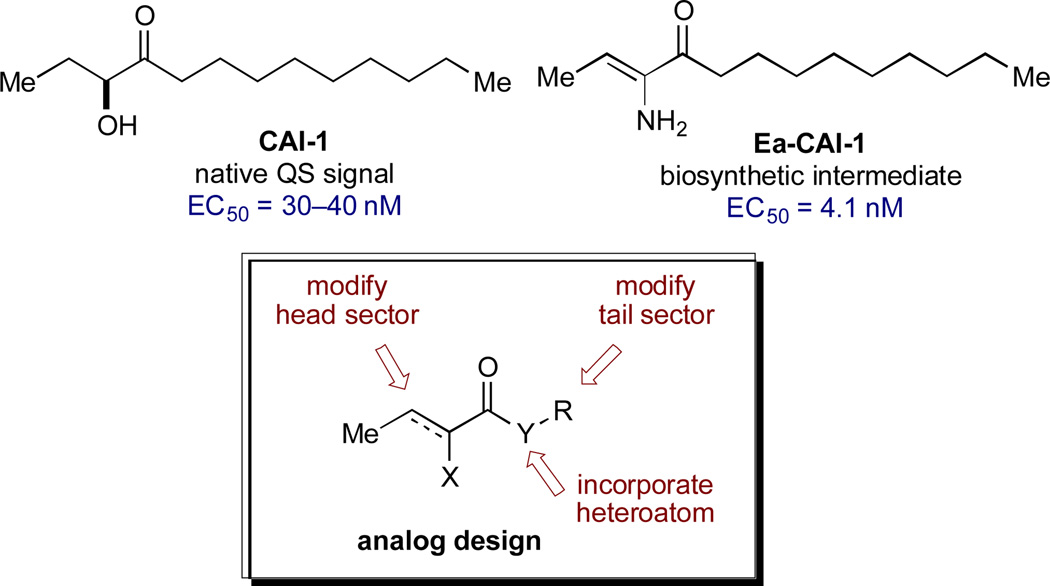

The small molecule CAI-1 [(S)-3-hydroxytridecan-4-one] is the primary QS signal in V. cholerae (Figure 2).28 This compound is produced by the CqsA synthase29,30 and detected by the membrane-spanning receptor, CqsS.31 While no structural information is available for CqsS, significant understanding of the ligand-receptor interaction exists from studies of modified ligands and CqsS mutants.32,33 Focused libraries of CAI-1 analogs have revealed a pattern of signal specificity based on the fatty acid “tail” (R) and variations both in the heteroatom (X) and the carbon structure of the “head” group (Figure 2, general structure). Specifically, these studies show that: (a) agonist activity is highly sensitive to variations in chain length and incorporation of conformational restrictions in the tail; (b) the ester series analogs (Y=O) are comparably active and provide a convenient platform for synthesis; and (c) attachment of phenyl substituents in the head group gives rise to the first antagonists of QS in V. cholerae.34,35 While several CAI-1 analogs have been identified with activity comparable to that of the native signal (CAI-1, EC50 = 30–40 nM), we aimed to expand the range of target structures to achieve higher potency and improved chemical stability.30

Figure 2.

CAI-1 Structure and CAI-1–Based Agonist Design.

We recently described the mechanism of biosynthesis of CAI-1, which revealed a chemically delicate intermediate (Ea-CAI-1, Figure 2) that is an order of magnitude more potent as a CqsS agonist compared to the native and longer-lived signal, CAI-1.29 The structure of Ea-CAI-1 provides a new template on which to design effective agonists, with the goal of identifying molecules that maintain the high activity of Ea-CAI-1 while possessing the chemical stability of a useful probe or drug candidate. We describe herein the synthesis and evaluation of a series of Ea-CAI-1 analogs. These analogs incorporate variations in the tail portion of the molecule as well as new heterocyclic head groups that mimic the ene-amino ketone moiety of the parent compound.

Results and Discussion

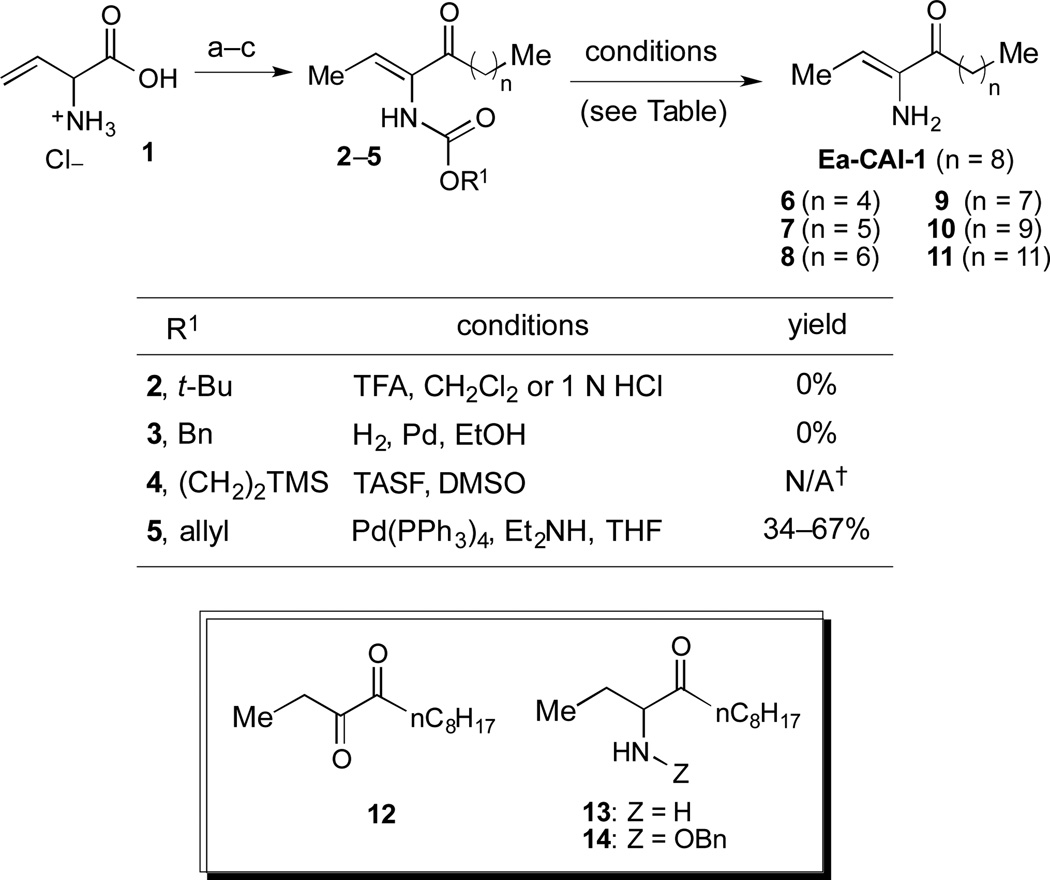

We first sought to prepare a series of Ea-CAI-1 analogs of varying tail lengths through adaptation of our previously described route to CAI-1 derivatives.36 Synthesis of these analogs required development of an effective enamine protecting group strategy. Deprotection of the ene-amino ketone functionality (2–5) is significantly complicated by the high propensity of the product (Ea-CAI-1) to undergo hydrolysis to the α-diketone 12. As shown in Scheme 1, efforts to employ a t-Boc protecting group strategy (2, R1 = tBu) were unsuccessful; this functionality could not be removed under standard conditions. Similarly, attempts to reductively remove the Cbz group of 3 (R1 = Bn) through exposure to H2 and Pd led to two major products, which were tentatively identified as aminoketone 13 and N-Cbz analog 14; these compounds presumably arise via preferential reduction of the alkene unit prior to benzyl cleavage. Although the N-Teoc protecting group (4) could be removed by treatment with excess TASF in DMSO, this transformation was very slow and yielded the desired adduct along with inseparable silyl-byproducts. The N-Alloc protecting group (5, R = allyl) was most effective; upon exposure to Pd(PPh3)4 and Et2NH, 5 was rapidly deprotected37 to deliver Ea-CAI-1 in good yield. Importantly, the product was isolated in pure form after passage through a short plug of silica gel deactivated with Et3N. Using this Alloc protecting group strategy, we successfully prepared a series of tail-length modified Ea-CAI-1 analogs (6–11).

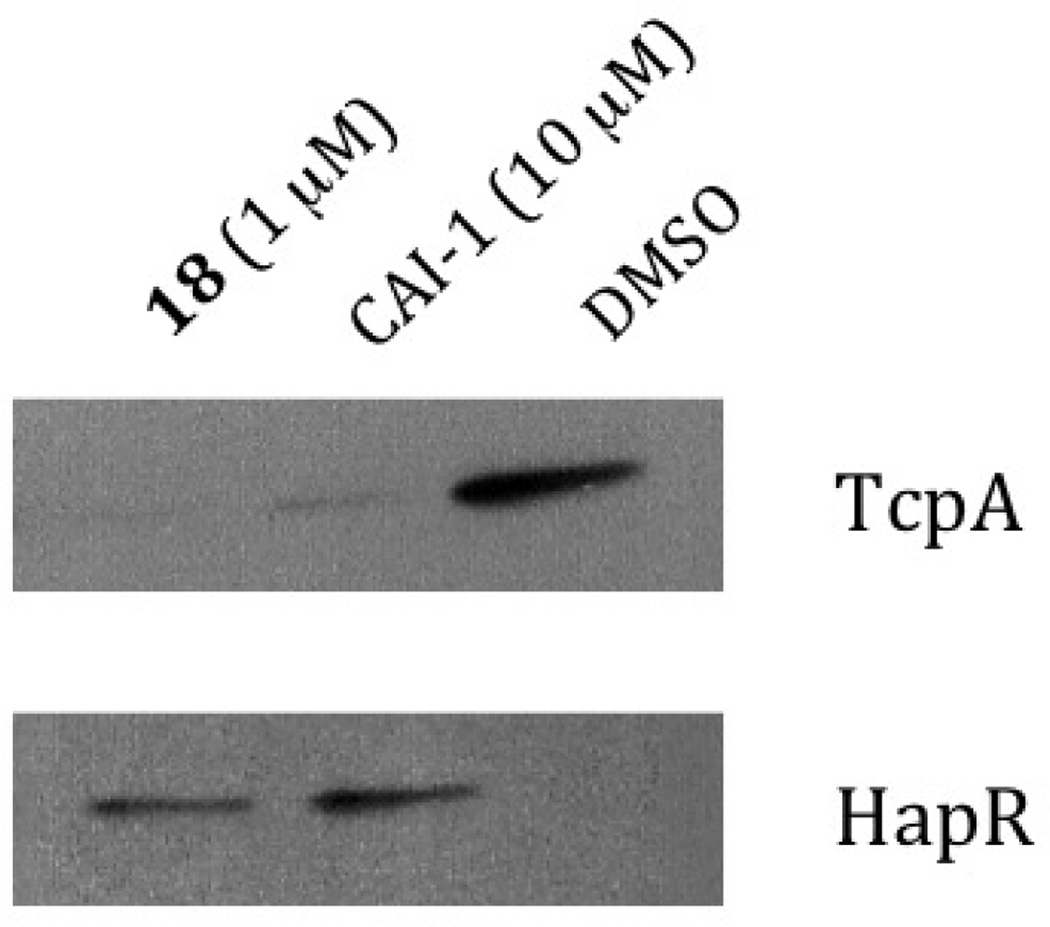

Figure 4.

CAI-1 and Compound 18 repress production of the V. cholerae toxin-correlated pilus TcpA and active production of HapR DMSO is used as the control see supporting Information.

The “tail-modified” analogs (6–11) were evaluated in a CqsS agonist bioassay (Table 1). Consistent with our earlier findings in the context of CAI-1 analogs,35 the V. cholerae CqsS receptor was somewhat promiscuous with respect to variations in tail length. The parent compound (Ea-CAI-1, n = 8) and the analog bearing a one-carbon truncated tail (9, n = 7) show low nM activity and full activation (entries 4 and 5). Other analogs with shorter (6–8) or longer (10) tail lengths were 1–2 orders of magnitude less potent, but nonetheless promoted full activation (entries 1–3 and 6). Only a very long tail gave an analog (11, n = 11) that was much less active, even at high concentrations. Interestingly, we do not observe direct correlation between maximum %response and EC50. Presumably, small perturbations in the structure of the ligand or binding site can disrupt the balance between kinase and phosphatase activity (see Figure 1). In all cases, the Ea-CAI-1 analogs were more active by an order of magnitude compared to the related examples from the native CAI-1 series, reported earlier.35, 36 These encouraging results prompted us to pursue the synthesis and evaluation of a broader range of Ea-CAI-1 analogs. In particular, we sought to explore the impact of replacing the enamino ketone “head” domain with more stable functionality, and of installing greater structural diversity onto the “tail” sector.

Table 1.

Effect of Ea-EAI-1 tail length on QS agonist activity.

| Entry |

|

EC50 (nM)a | % Responseb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6, n = 4 | 590 | 100 |

| 2 | 7, n = 5 | 290 | 120 |

| 3 | 8, n = 6 | 40 | 109 |

| 4 | 9, n = 7 | 2.6 | 112 |

| 5 | Ea-CAI-1, n = 8 | 4.1 | 100 |

| 6 | 10, n = 9 | 170 | 105 |

| 7 | 11, n = 11 | >5000 | 38 |

Values were determined using the CqsS agonist bioassay.

All EC50 values are the mean of triplicate analyses.

Percent maximal bioluminescence with respect to Ea-CAI-1, which is set at 100%. For more information, see Supporting Information.

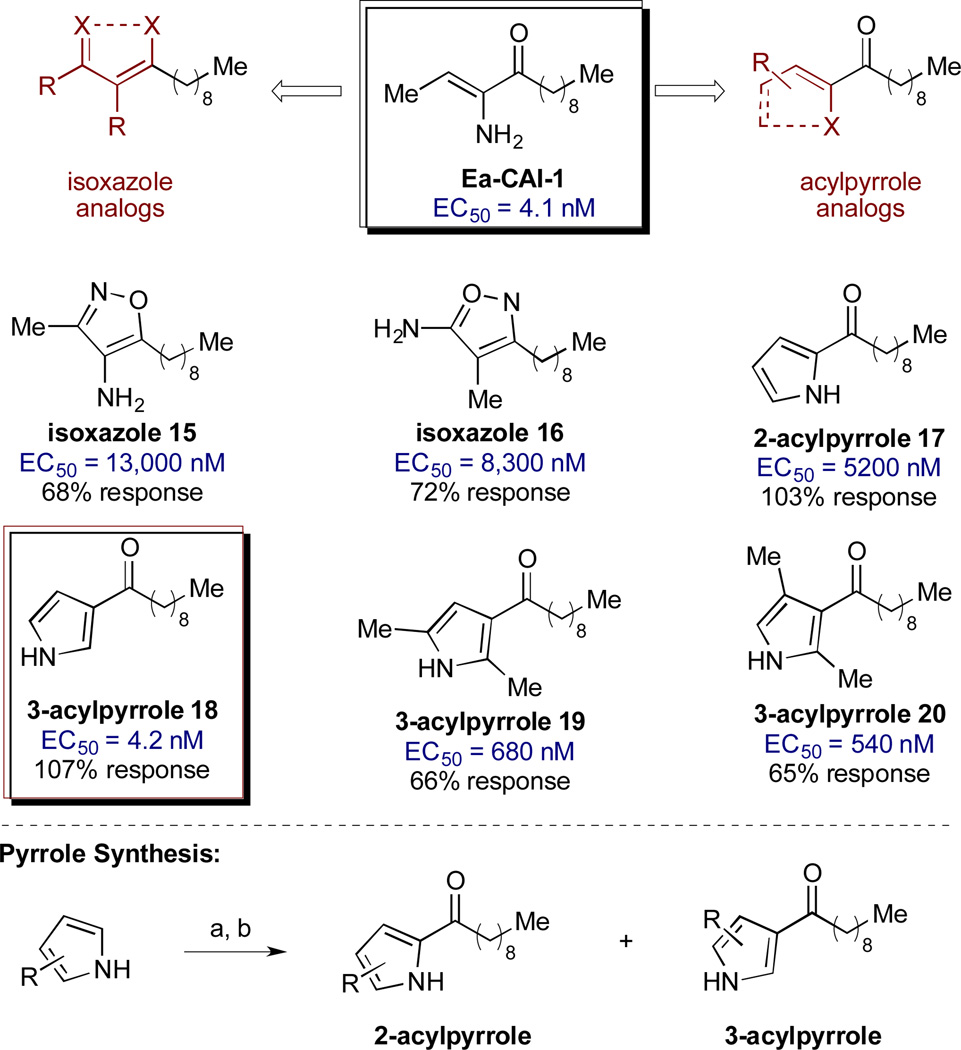

We first examined the effects of head group variation on agonist activity. We postulated that the stereoelectronic features of the ene-amino ketone motif of the parent compound could be mimicked through substitution with more stable isoxazole or acylpyrrole functional motifs (Scheme 2).38 A series of analogs was synthesized and evaluated for agonist activity (see Scheme 2 and Supporting Information for details). Neither of the isoxazole analogs showed significant activity (15 and 16, EC50 > 8000 nM). However, promising results were obtained with the series of analogs bearing acyl pyrrole head groups; importantly, these motifs retain both ketone and α-heteroatom hydrogen bond donor functionality. For the initial analysis, compounds 17 and 18 were prepared as a readily separable mixture of isomers for biological evaluation (Scheme 2). While both analogs elicit the full level of QS response, the 3-acyl isomer 18 exhibits an EC50 >1000-fold more potent than the 2-acyl isomer. The EC50 value of 4.2 nM identifies 18 as comparable in activity to the parent compound, Ea-CAI-1. Incorporation of additional substituents onto the 3-acyl pyrrole (19 and 20) resulted in lower agonist activity, as indicated by the higher EC50 and lower % response.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Ea-CAI-1 and tail length–modified analogs. Reagents and conditions: (a) Amine production (see supporting Information for details); (b) HNMe(OMe)•HCl, EDC, HOBt, Et3N, THF (42–58% from 1); (c) R2MgX (71–93%).†These conditions led to quantitative consumption of the starting material and slow formation of the desired product along with inseparable silyl byproducts.

The 3-acylpyrrole heterocyclic motif has therefore been identified as a viable, chemically stable bioisostere of the native Ea-CAI-1 head group.39 Having identified a suitable replacement for the delicate enamino ketone moiety, we next probed the effect of variations in the tail structure on CqsS agonist activity (Table 2). We observed that analogs bearing a C9 or a C10 fatty acid tail were most potent and provided full activation (entries 4 and 5); these findings are comparable to the structure-activity relationships previously observed in the α-enamino ketone series. The other tail lengths were less potent and gave no more than 50% activation.

Table 2.

Effect of 3-acylpyrrole tail on QS agonist activity.

| Entry |  |

EC50 (nM)a | % Responseb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21, n = 4 | 1200 | 14 |

| 2 | 22, n = 5 | 740 | 43 |

| 3 | 23, n = 6 | 51 | 50 |

| 4 | 24, n = 7 | 8.2 | 101 |

| 5 | 18, n = 8 | 4.2 | 107 |

| 6 | 25, n = 9 | 300 | 29 |

Values were determined using the CqsS agonist bioassay.

All EC50 values are the mean of triplicate analyses.

Percent maximal bioluminescence with respect to Ea-CAI-1, which is set at 100%. For more information, see Supporting Information.

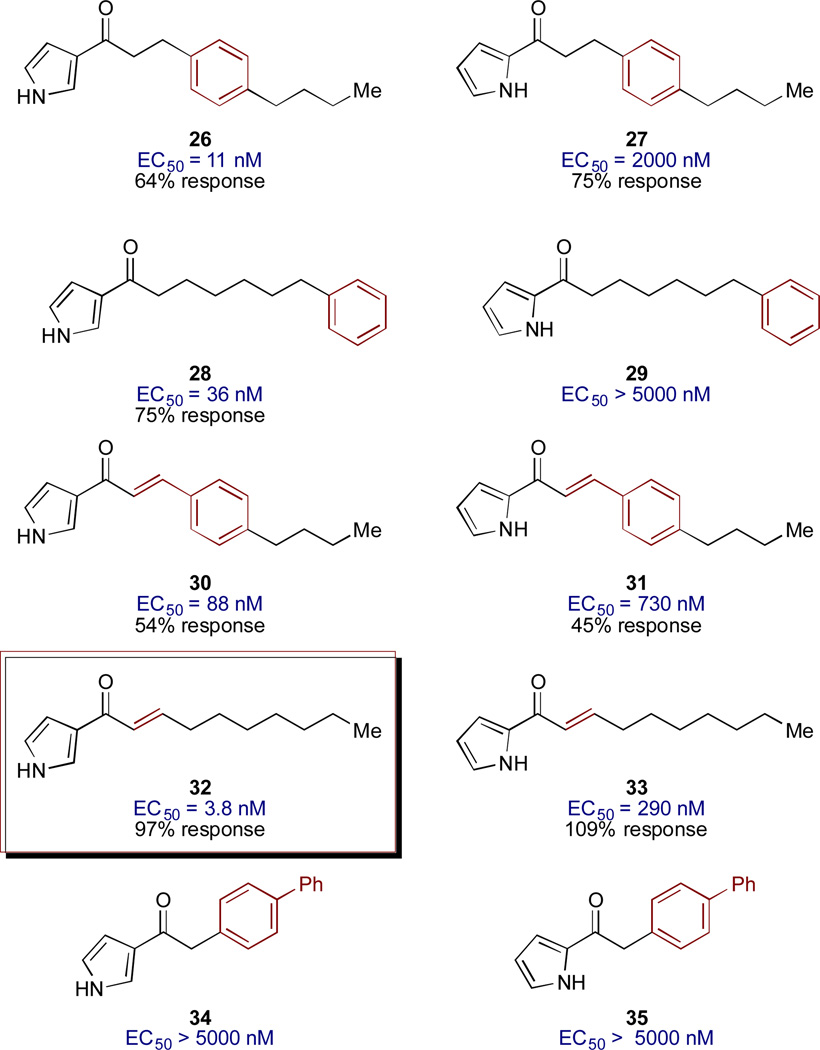

Further probing of the effect of tail structure involved introduction of simple E-alkene units and benzene rings, with the goal of examining the effects of conformational restriction and steric perturbation within the acyl tail (Figure 3).40,41 In all cases in which significant activity was observed (EC50 values <5000 nM), the 3-acyl pyrrole analogs were much more potent than the corresponding 2-acyl pyrrole analogs. Introduction of a benzene ring in the 3-acylpyrrole series produced highly active analogs; compounds 26 and 29 show activities only 3- to 10-fold lower than the best agonists (Ea-CAI-1 and acylpyrrole 18). This result suggests substantial steric flexibility in the presumed hydrophobic binding site for the tail group and expands the design opportunities for further exploration of the tail structure. It should be noted, however, that the maximum percent activation is lower for these benzyl analogs (54–75%). In our previous SAR work, focused on the structure of the fatty acid tail of CAI-1, we had observed that the conformational restriction provided by incorporation of an E-alkene unit conferred enhanced potency over the corresponding fully saturated analog. Similarly, in the 3-acylpyrrole Ea-CAI-1 series, incorporation of an E-alkene moiety (32) leads to one of the most potent agonists of V. cholerae QS yet discovered; compound 32, with an EC50 of 3.8 nM, is slightly more potent than both Ea-CAI-1 (4.1 nM) and acyl-pyrrole 18 (4.2 nM). Interestingly, incorporation of a biphenyl unit in the acyl chain leads to essentially inactive analogs (34 and 35).

Figure 3.

Modified tail structures in the 2- and 3-acylpyrrole motif.

Having identified a stable and highly potent lead compound (18), we examined its effect on the QS circuit in V. cholerae. In vivo, HapR is a transcription factor that functions as one of two master QS regulators in V. cholerae. Agonism of CqsS leads to increased production of HapR and HapR, in turn, drives the high-cell density gene expression program, which leads to repression of the expression of genes required for virulence and biofilm formation.1 Figure 4 shows that production of HapR increased in response to 1 µM of the 3-acyl pyrrole 18 to a level similar to that achieved from exposure to 10 µM of the native ligand, CAI-1. Conversely, production of TcpA, the toxin-co-regulted pilis protein subunit A, and a major V. cholerae virulence factor is repessed by both CAI-1 and compound 18. These results are consistent with the heterocyclic analog 18 acting on CqsS in a manner similar to CAI-1.

Given the possibility for further development of the 3-acylpyrrole 18 as a potential anti-virulence agent, we preliminarily investigated the cytotoxicity of this analog in bacteria and in a murine 3D3 fibroblast cell line. Consistent with our proposal that the molecule functions by influencing QS-controlled behaviors and not by altering growth, we observed that 18 is not toxic to bacteria. No decrease in OD600 occurs when V. cholerae is treated with 18 at concentrations up to 25,000 nM (i.e. levels more than 5000-fold higher than the EC50 for 18, see Supporting Information). Likewise, 18 was tolerated by murine 3T3 fibroblast cells at concentrations up to 23,000 nM, as assessed by optical microscopy (see Supporting Information).

Despite the high activity of this class of molecules with respect to the V. cholerae CqsS receptor, none of the 3-acyl pyrrole analogs showed significant activity against the Vibrio harveyi CqsS receptor (data not shown). This result is perhaps surprising, given the high homology between these two QS receptors; however, it is consistent with our earlier observations that, compared to the V. cholerae receptor, the V. harveyi receptor is less tolerant of structural perturbations to the cognate ligand.32

Conclusion

Ea-CAI-1, a delicate biosynthetic intermediate and the most potent natural agonist of QS in V. cholerae, was used as a starting point in designing chemically stable analogs with high potency in activating the CqsS receptor. Several derivatives of the 3-acylpyrrole structure have activities equivalent to Ea- CAI-1 and are promising leads for developing new therapeutics to control V. cholerae infection. The 3-acylpyrrole with the C9 alkyl tail (18) functions analogously to the native signal, CAI-1, in regulating production of the transcription factor HapR and the virulence factor, TcpA. Compound 18 also does not inhibit bacterial growth nor does it show toxicity toward a mamalian cell line, and is therefore a promising candidate for further development.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Variation of the Ea-CAI-1 head group: isoxazole and acylpyrrole analogs. Reagents and conditions: (a) MeMgBr, Et2O; (b) n-C9H19COCl. see Supporting Information for details on the synthesis of the acylpyrrole and isoxazole analogs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rebecca M. Lambert for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, Hank Song for assistance in compound synthesis, and Cara Carraher for assistance with 3T3 cell culture. Financial support was provided by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants 5R01GM065859 and 5R01AI054442.

Footnotes

† Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures, structural proofs, and spectral data for all new compounds are provided. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and References

- 1.Ng W-L, Bassler BL. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassler BL. Cell. 2002;109:421–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuqua WC, Winans SC, Greenberg EP. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;50:727–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters CM, Bassler BL. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:319–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cegelski L, Marshall GR, Eldridge GR, Hultgren SJ. Nat Rev Micro. 2008;6:17–27. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clatworthy AE, Pierson E, Hung DT. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:541–548. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1432. doi: 10.1039/b703021p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hentzer M, Wu H, Andersen JB, Riedel K, Rasmussen TB, Bagge N, Kumar N, Schembri MA, Song Z, Kristoffersen P, et al. EMBO J. 2003;22:3803–3815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Njoroge J, Sperandio V. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:201–210. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2010;9:117–128. doi: 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swem LR, Swem DL, O'Loughlin CT, Gatmaitan R, Zhao B, Ulrich SM, Bassler BL. Molecular Cell. 2009;35:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:1135–1147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z, Miyashiro T, Tsou A, Hsiao A, Goulian M, Zhu J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9769–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802241105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith RS, Iglewski BH. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2003;6:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadell CD, Xavier JB, Levin SA, Foster KR. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MB, Skorupski K, Lenz DH, Taylor RK, Bassler BL. Cell. 2002;110:303–314. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. Developmental Cell. 2003;5:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu J, Miller MB, Vance RE, Dziejman M, Bassler BL, Mekalanos JJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3129–3134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052694299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan F, March JC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11260–11264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001294107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Defoirdt T, Bossier P, Sorgeloos P, Verstraete W. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1239–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gode-Potratz CJ, McCarter LL. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:4224–4237. doi: 10.1128/JB.00432-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roh JB, Lee MA, Lee HJ, Kim SM, Cho Y, Kim YJ, Seok YJ, Park SJ, Lee KH. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34775–34784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao CP, Lo HR, Lin JH, Hor LI. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:2557–2565. doi: 10.1128/JB.01259-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q, Liu Q, Ma Y, Rui H, Zhang Y. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007;103:1525–1534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng W-L, Perez L, Cong J, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002767. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins DA, Pomianek ME, Kraml CM, Taylor RK, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. Nature. 2007;450:883–886. doi: 10.1038/nature06284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei Y, Perez LJ, Ng W-L, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:356–365. doi: 10.1021/cb1003652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly RC, Bolitho ME, Higgins DA, Lu W, Ng W-L, Jeffrey PD, Rabinowitz JD, Semmelhack MF, Hughson FM, Bassler BL. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:891–895. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henke JM, Bassler BL. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:6902–6914. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6902-6914.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng W-L, Perez LJ, Wei Y, Kraml C, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;79:1407–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng W-L, Wei Y, Perez LJ, Cong J, Long T, Koch M, Semmelhack MF, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:5575–5580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001392107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez LJ, Ng W-L, Marano P, Brook K, Bassler BL, Semmelhack MF. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:9669–9681. doi: 10.1021/jm300908t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolitho ME, Perez LJ, Koch MJ, Ng W-L, Bassler BL, Semmelhack MF. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:6906–6918. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng W-L, Perez LJ, Wei Y, Kraml C, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;79:1407–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genêt JP, Blart E, Savignac M, Lemeune S, Lemaire-Audoire S, Bernard JM. Synlett. 1993;1993:680–682. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourbeau MP, Rider JT. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3679–3680. doi: 10.1021/ol061260+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meanwell NA. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2529–2591. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferenczy GG, Keserũ GM. Drug Discov. Today. 2010;15:919–932. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freire E. Drug Discov. Today. 2008;13:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.