Abstract

Context

Substantive equity-focused policy changes in Ontario, Canada have yet to be realized and may be limited by a lack of widespread public support. An understanding of how the public attributes inequalities can be informative for developing widespread support. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine how Ontarians attribute income-related health inequalities.

Methods

We conducted a telephone survey of 2,006 Ontarians using random digit dialing. The survey included thirteen questions relevant to the theme of attributions of income-related health inequalities, with each statement linked to a known social determinant of health. The statements were further categorized depending on whether the statement was framed around blaming the poor for health inequalities, the plight of the poor as a cause of health inequalities, or the privilege of the rich as a cause of health inequalities.

Results

There was high agreement for statements that attributed inequalities to differences between the rich and the poor in terms of employment, social status, income and food security, and conversely, the least agreement for statements that attributed inequalities to differences in terms of early childhood development, social exclusion, the social gradient and personal health practices and coping skills. Mean agreement was lower for the two statements that suggested blame for income-related health inequalities lies with the poor (43.1%) than for the three statements that attributed inequalities to the plight of the poor (58.3%) or the eight statements that attributed inequalities to the privilege of the rich (58.7%).

Discussion

A majority of this sample of Ontarians were willing to attribute inequalities to the social determinants of health, and were willing to accept messages that framed inequalities around the privilege of the rich or the plight of the poor. These findings will inform education campaigns, campaigns aimed at increasing public support for equity-focused public policy, and knowledge translation strategies.

Introduction

Income-related health inequalities in Canada are well recognized by the health, policy, and research communities, as is the role of the social determinants of health (SDOH), such as education, housing, and job security, in producing and maintaining these inequalities [1]–[9]. Indeed, it has been argued that income inequality is the key determinant of health among Canadians [10]. These stakeholders also recognize that society bears much of the responsibility for health inequality, and accordingly, that governmental policies and programs can mitigate marginalization [11], [12]. As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on the Social Determinants of Health endorsed the incorporation of the SDOH into governmental policies and programs [13]. In Canada, there has also been a move towards addressing health inequalities at the local, provincial, and national levels, including the promotion of the SDOH by select local public health units in the province of Ontario (e.g. Sudbury and District Health Unit and Peterborough County-City Health Unit), the use of health equity impact assessment tools to improve decision-making in Ontario [14] and cross-sectoral policies in the province of Quebec [15], and the establishment of equity-focused research priorities within federal research funding bodies such as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [16]. Despite these initial steps, substantive policy change has yet to be realized in most Canadian jurisdictions, including Ontario, the country's most populous and diverse province. This relative inaction may be due to competing social and political interests, but may also reflect a lack of widespread public attention to the need for such policies [17]. Tellingly, the WHO Commission endorsed raising public awareness regarding the SDOH as a key step to “closing the gap” in health “within a generation”, suggesting that public awareness may serve as a significant motivating factor for policymakers if it existed [13].

Our previous research suggests that only a small majority of Ontarians are aware of income-related health inequalities in the province, with 53% agreeing that ‘the rich are much healthier than the poor’ [18]. As well, we have shown that certain sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, education, and political affiliation, are associated with awareness of income-related health inequalities [18]. These and other characteristics might also influence how one attributes the causes of health inequalities. Attribution theory posits that individuals understand social phenomena by attributing the causes of such phenomena to internal or external factors (i.e. caused by individual dispositions or by social factors outside of the individual's control) [19]. This theory also suggests that if someone has not experienced a particular situation or condition, such as those that make up the SDOH, then he or she is less likely to recognize the role that the SDOH may play in producing and maintaining inequalities. He or she may then subsequently see no reason to support equity-focussed policies [19], [20]. This tendency of the observer to then attribute outcomes to internal factors instead of to external factors has been called “the fundamental attribution error” [21]. In this way, the public's beliefs and judgments about the SDOH, and their potential support for equity-related policies, may be influenced by their sociodemographic circumstances [19], [22]–[24].

An understanding of how Ontarians attribute income-related health inequalities can be used to inform effective framing of messages aimed at increasing public awareness of inequalities and support for policy change to promote health equity. Effective messages should include emphasis on the importance of external factors, but we must also ascertain what messages the general public, and population subgroups, are willing to accept. For example, Niederdeppe et al.'s Message Design Strategy Framework for Raising Awareness of SDOH and Population Health Disparities states that messaging can frame inequalities as being within the control of the disadvantaged individual, being beyond the control of that individual, or some combination of the two, with the most effective messaging emphasizing external factors but acknowledging the role of the individual[19]. Although this framework was developed in the American context, it follows that how the message on health inequalities is framed can affect how willing Ontarians will be to absorb the messages. Linked to this is the push in the health promotion literature to move beyond understanding the plight of disadvantaged and poor communities toward an appreciation of the maintenance of privilege by advantaged groups [25], [26]. As a result, messages around income-related health inequalities could be more or less agreeable to the Ontario public, and to various subgroups, depending on if the messages frame the poor as being responsible for their relatively unequal and worse health (what we refer to as ‘blame’), or if they explain inequalities as related to external factors in broader society such as the social advantages or privilege of the rich, or the social disadvantages of the poor (what we refer to as ‘privilege’ and ‘plight’ respectively).

With these considerations in mind, this paper reports on survey results of how Ontarians attribute differences in health between the rich and poor. The data presented here are part of a larger body of work where the overarching aim is to better understand how to increase public support for health equity by exploring Ontarians' awareness of income-related health inequalities, their attributions of these inequalities, and their opinions about solutions to inequalities. Specifically, this paper examines Ontarians' attributions of income-related health inequalities relative to the SDOH, their attributions relative to the framing of messages, and how various sociodemographic factors influence these attributions.

Methods

Ethics Statement

The study, and its consent procedures, received approval by the University of Toronto's Office of Research Ethics. Individuals were asked if they would participate in the survey, and when they verbally agreed, this was taken to imply consent. This is common practice in telephone interview surveys that are deemed to present little or no risk to participants, so no written consent is generally obtained. As well, it was not feasible to obtain written consent due to the nature of the survey (i.e. conducted by telephone by a third party market-based research firm via random digit dialling). All telephone surveys were recorded for quality control purposes, and all responses were entered real-time using computer-assisted telephone interview technology. The process, as documented by the market-based research firm, indicated that of 69,906 numbers called, there were a total of 33,530 individuals asked to participate with 9.24% of persons asked to complete the survey doing so.

Study Sample

Details of the study methods have been previously published [18]. Briefly, we surveyed 2,006 Ontarians aged 18 years and over through a telephone interview survey using random digit dialing. A sample size calculation indicated that this would provide a 3.0% margin of error with 95% confidence relative to the Ontario population.

Survey

The survey included questions pertaining to three broad themes: (1) awareness of income-related health inequalities, (2) attributions of income-related health inequalities, and (3) possible solutions to income-related health inequalities. Results related to the first theme have been previously published [18]. The outcomes examined in this analysis relate to the second theme only.

We analyzed responses to thirteen Likert items, with each attribution statement linked to a particular SDOH (Table 1). As many typologies for the SDOH exist, each with benefits and limitations when considering income-related health inequalities, we have drawn our list of determinants from a variety of sources, including the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada to ensure relevance to the Canadian context [27]. The list of determinants was chosen by consensus by the research team, with the goal of achieving a thorough list and a survey that would not be onerous for respondents. The statements were further categorized depending on whether the statement was framed around blaming the poor for health inequalities (two statements), the plight of the poor as a cause of health inequalities (three statements), or the privilege of the rich as a cause of health inequalities (eight statements). Due to the focus on the SDOH, statements in the latter two categories predominated.

Table 1. Thirteen statements presented to survey respondents on attributions of income-related health inequalities, the social determinant of health to which the statement attributed inequalities, and whether the statement was framed around blaming the poor, the plight of the poor, or the privilege of the rich.

| Statement | Social Determinant of Health | Message Framing: Blame, Plight, or Privilege |

| The poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles - they smoke and drink more, don't exercise and eat junk food | Health behaviours | Blames the poor |

| The poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life | Social exclusion | Blames the poor |

| The poor smoke and drink more to help them cope with the stress and anxiety in their lives; that is why they have poor health | Personal health practices and coping skills | Plight of the poor |

| The poor are less healthy because they have more stress and anxiety in their lives than those who are better off | Stress | Plight of the poor |

| If you work in a poorly paying job, the insecurity you feel can have a bad effect on your health | Employment and working conditions | Plight of the poor |

| The rich are healthier because they live in better houses in better neighbourhoods | Environment and housing | Privilege of the rich |

| The rich are healthier because they have money to buy things that make them healthy | Income | Privilege of the rich |

| Even though everyone in Ontario has access to medical care, the rich get more out of the health care system than the poor | Access to health care | Privilege of the rich |

| The rich have more choices and more control over their lives and health than the poor | Social status | Privilege of the rich |

| The rich are healthier because they have better access to high quality food | Food security | Privilege of the rich |

| Some people are at the top of the social ladder and some people are at the bottom; this is why the rich are healthier than the poor | Social gradient | Privilege of the rich |

| The rich are healthier because their childhood experiences are much better | Early childhood development | Privilege of the rich |

| The rich are healthier because they have more education and know how to stay healthy | Education and literacy | Privilege of the rich |

For all statements, participants were given the options of strongly agreeing, agreeing, disagreeing, strongly disagreeing, providing a neutral response, or refusing to answer. The proportion refusing to answer ranged from 0.2% to 2.8%. To investigate participant characteristics that may influence how one attributes health inequalities, political affiliation and demographic information were also collected. Demographic characteristics used in this analysis include sex, age group (18–34 years, 35–54 years, 55+ years), area of residence (urban vs. rural), immigration status (immigrated more than 10 years ago, immigrated 10 years ago or less, Canadian-born), visible minority status, total annual household income (< $20,000, $20,000–< $40,000, $40,000 – <$60,000, $60,000 – <$80,000, $80,000 – <$100,000, $100,000+), highest attained education (high school diploma or lower versus higher than high school), and whether participants were employed at the time of the survey. Political affiliation was gauged in response to the question, “If the election were being held today, do you think you would vote for the Progressive Conservative, Liberal, New Democratic Party (NDP), Green, or some other candidate?” The former three parties are the parties currently represented in the Ontario legislative assembly, and can very generally be defined as right to left wing, respectively. Participants who indicated affiliation with the Green Party or another candidate were classified as ‘Other’. We also examined a fifth category of political affiliation that comprised participants who either didn’t know who they would vote for or who refused to answer the question.

Analysis

We tabulated the proportion of survey responses to each of the thirteen statements. We then classified responses as a binary measure indicating some level of agreement, versus some level of disagreement or a neutral response. To determine the association of sociodemographic characteristics with survey responses, we conducted multivariable logistic regression. For this analysis, all characteristics that were associated with agreement, based on a significance level of 0.2, were eligible for inclusion in the model. Spearman correlation coefficients between all significant subgroup characteristics were examined to identify collinearity between predictors. We then used a manual backward stepwise approach to identify a parsimonious list of characteristics that independently predicted agreement with the attribution statements.

For all analyses, data were weighted to provide estimates that were representative of the provincial population. Weights were based on provincial age and sex distributions according to the 2006 Canadian Census. SAS Version 9.3 was used for all analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The participation rate and demographic profile of study participants are described elsewhere [18]. Study participants were generally representative of the Ontario population based on the 2006 Census. Briefly, females composed 52% of the sample. Close to 30% of participants reported an annual household income of $40,000 or less, 26.5% reported a high school diploma or less as the highest attained education, and 6.2% reported current unemployment. When asked who they would vote for if an election were being held today, 24.5% reported Progressive Conservative, 21.8% reported Liberal, 11% reported NDP, 13.2% opted for another party, and 29.6% of participants did not know who they would vote for or refused to answer the question.

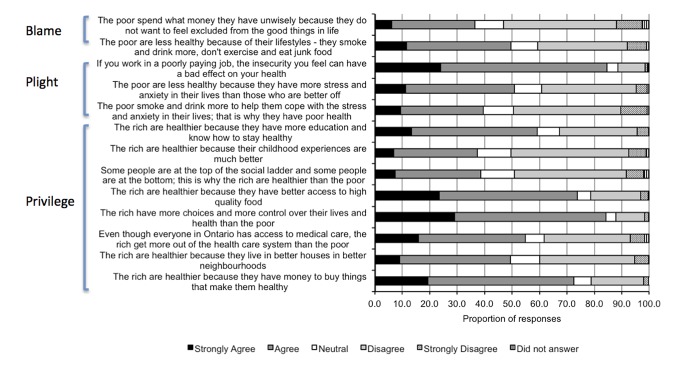

Almost 85% strongly agreed or agreed that income-related health inequalities could be attributed to the poor having greater job insecurity, or to the rich having more choices and control over their lives than the poor (Figure 1). There was also high agreement for statements that implicated differences in food security (74%) and in income that enabled the rich to “buy things that make them healthy” (72%). Conversely, the least agreement was seen for statements that attributed income-related health inequalities to unhealthy coping behaviours (40%), the social gradient (39%), unwise spending amongst the poor (37%), and better early childhood experiences among the rich (37%). The framing of the message seemed to affect likelihood of agreement. Mean agreement was lower for the two statements that suggested blame for income-related health inequalities lies with the poor (43.1%) than for the three statements that attributed inequalities to the plight of the poor (58.3%) or the eight statements that attributed inequalities to the privilege of the rich (58.7%).

Figure 1. Distribution of responses.

Tables 2 and 3 describe the results of multivariable logistic regression, which identified sociodemographic characteristics associated with agreement with statements. Of the characteristics that met inclusion for the multivariate model based on univariate analyses, only two, immigration status and visible minority, appeared to be correlated (r = 0.4982). We included visible minority over immigration status in multivariate models, as this is arguably a better representation of how one may be viewed socially [28]. Older age was associated with a higher likelihood of agreement with almost all statements, but with only one of the three “plight” statements. Men were more likely than women to agree with both “blame” statements and less likely to agree that “the rich get more out of the health care system than the poor”. Visible minority status, lower income, lower education, and certain political affiliations were significantly associated with agreement across statements. Visible minorities were more likely to agree with both “blame” statements, with most (two of the three) “plight” statements, and with statements relevant to the social gradient and childhood experiences. Respondents tended to be more likely to agree across statements as their income decreased, with the difference in response most striking for “the poor are less healthy because they have more stress and anxiety in their lives than those who are better off”. People of low education attainment tended to be more likely to agree across statements but were less likely to agree that “the rich are healthier because they have more education and know how to stay healthy”. Supporters of the NDP, Canada's most left-leaning party, were less likely to agree that the poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles, were more likely to agree that the rich are healthier because of access to high quality food, and along with “Other” voters (many of whom supported the Green party, which is generally known for an environmental emphasis yet fiscal conservatism), were more likely to agree that the rich get more out of the health care system than the poor. Supporters of the Progressive Conservatives (PCs), Canada's most right-leaning party, were more likely to agree that “the poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life”.

Table 2. Results of multivariate logistic regression: statements framed around blaming the poor or the plight of the poor.

| Blame | Plight | ||||

| Health behaviours | Social exclusion | Personal health practices and coping skills | Stress | Employment and working conditions | |

| Proportion agreement | 49.6 | 36.5 | 39.5 | 50.9 | 84.6 |

| Age group [Reference: 18–34] | |||||

| 35–54 | 1.27 (0.99 – 1.62) | 1.02 (0.79 – 1.34) | 1.38 (1.07 – 1.79) | ||

| 55+ | 2.70 (2.05 – 3.55) | 1.41 (1.06 – 1.88) | 1.79 (1.36 – 2.36) | ||

| Sex (Male) | 1.61 (1.32 – 1.98) | 1.80 (1.45 – 2.23) | 1.38 (1.12 – 1.69) | ||

| Residence in a Census Metropolitan Area | |||||

| Place of birth and immigration status [Reference: Born in Canada] | |||||

| Born outside of Canada and immigrated >10y ago | |||||

| Born outside of Canada and immigrated < = 10y ago | |||||

| Visible minority | 1.46 (1.11 – 1.92) | 1.90 (1.43 – 2.53) | 1.75 (1.33 – 2.30) | 1.43 (1.10 – 1.87) | |

| Annual household income [Reference: <$20,000] | |||||

| $20,000 – <$40,000 | 0.96 (0.65 – 1.42) | 0.77 (0.53 – 1.13) | 0.79 (0.54 – 1.17) | ||

| $40,000 – <$60,000 | 0.83 (0.57 – 1.23) | 0.73 (0.50 – 1.07) | 0.71 (0.48 – 1.04) | ||

| $60,000 – <$80,000 | 0.69 (0.46 – 1.03) | 0.56 (0.38 – 0.83) | 0.51 (0.35 – 0.76) | ||

| $80,000 – <$100,000 | 0.58 (0.38 – 0.90) | 0.66 (0.44 – 1.00) | 0.47 (0.31 – 0.72) | ||

| > = $100,000 | 0.50 (0.34 – 0.74) | 0.43 (0.29 – 0.62) | 0.39 (0.27 – 0.57) | ||

| Highest education < = highschool diploma | 1.73 (1.36 – 2.22) | 1.39 (1.10 – 1.77) | 1.44 (1.13 – 1.83) | ||

| Political affiliation [Reference: Don't know/refused] | - | ||||

| PC | 1.00 (0.76 – 1.33) | 1.34 (1.00 – 1.79) | |||

| Liberal | 1.23 (0.92 – 1.64) | 0.81 (0.59 – 1.10) | |||

| NDP | 0.66 (0.46 – 0.94) | 1.06 (0.73 – 1.54) | |||

| Other | 1.04 (0.74 – 1.46) | 1.01 (0.71 – 1.44) | |||

The variable for ‘currently unemployed’ not shown as it is not included in any final model.

Table 3. Results of multivariate logistic regression: questions framed around the privilege of the rich.

| Income | Environment and housing | Access to health care | Social status | Food security | Social gradient | Early childhood development | Education and literacy | |

| Proportion agreement | 72.4 | 49.4 | 54.9 | 84.2 | 73.8 | 38.6 | 37.4 | 59.1 |

| Age group [Reference: 18–34] | ||||||||

| 35–54 | 1.27 (0.98 – 1.65) | 1.34 (1.02 – 1.64) | 1.65 (1.21 – 2.25) | 1.29 (0.99 – 1.68) | 1.64 (1.26 – 2.13) | 1.49 (1.15 – 1.93) | 1.64 (1.30 – 2.08) | |

| 55+ | 1.46 (1.10 – 1.93) | 1.61 (1.24 – 2.09) | 2.75 (1.89 – 4.03) | 1.64 (1.22 – 2.19) | 2.23 (1.68 – 2.95) | 2.35 (1.77 – 3.11) | 2.52 (1.93 – 3.28) | |

| Sex (Male) | 0.72 (0.59 – 0.88) | 1.41 (1.15 – 1.74) | ||||||

| Residence in a Census Metropolitan Area | 1.41 (1.11 – 1.79) | 1.49 (1.20 – 1.86) | ||||||

| Place of birth and immigration status [Reference: Born in Canada] | ||||||||

| Born outside of Canada and immigrated >10y ago | 1.62 (1.26 – 2.08) | |||||||

| Born outside of Canada and immigrated < = 10y ago | 1.54 (0.97 – 2.44) | |||||||

| Visible minority | 1.70 (1.29 – 2.24) | 2.40 (1.82 – 3.15) | ||||||

| Annual household income [Reference: <$20,000] | - | |||||||

| $20,000 – <$40,000 | 0.76 (0.53 – 1.10) | 0.60 (0.41 – 0.88) | 0.73 (0.52 – 1.12) | |||||

| $40,000 – <$60,000 | 0.66 (0.46 – 0.96) | 0.64 (0.43 – 0.62) | 0.77 (0.52 – 1.12) | |||||

| $60,000 – <$80,000 | 0.58 (0.39 – 0.84) | 0.53 (0.36 – 0.79) | 0.73 (0.49 – 1.09) | |||||

| $80,000 – <$100,000 | 0.48 (0.32 – 0.72) | 0.46 (0.30 – 0.69) | 0.54 (0.36 – 0.83) | |||||

| > = $100,000 | 0.45 (0.31 – 0.64) | 0.61 (0.42 – 0.88) | 0.54 (0.37 – 0.80) | |||||

| Highest education < = highschool diploma | 1.39 (1.09 – 1.77) | 0.71 (0.56 – 0.89) | ||||||

| Political affiliation [Reference: Don't know/refused] | ||||||||

| PC | 1.05 (0.80 – 1.38) | 0.77 (0.57 – 1.04) | ||||||

| Liberal | 1.08 (0.81 – 1.42) | 1.00 (0.73 – 1.38) | ||||||

| NDP | 1.50 (1.05 – 2.12) | 1.47 (0.97 – 2.24) | ||||||

| Other | 1.76 (1.25 – 2.46) | 1.05 (0.72 – 1.54) |

The variable for ‘currently unemployed’ not shown as it is not included in any final model.

Discussion

In this survey of Ontarians, we found that respondents were most willing to attribute income-related health inequalities to differences between the rich and poor in terms of employment, social status, income and food security, and least willing to attribute inequalities to differences in terms of early childhood development, social exclusion, the social gradient and personal health practices and coping skills. These distinctions may reflect a better understanding of some social determinants by the public than others, and are important for health equity advocates to consider when working to create widespread support for health equity-focused public policy in Ontario. These findings identify policy solutions that the general public may be more willing to support at present, as well as issues where more education is needed to improve popular understanding and support. We also found that respondents were generally more likely to agree with statements that were framed around the plight of the poor or the privilege of the rich and less likely to agree with statements that implied the poor were to blame for income-related health inequalities. This finding suggests a willingness on the part of Ontarians to accept a more macro-social understanding of the determinants of health. While there was no noticeable preference for the “plight” frame over the “privilege” frame, it must be noted that mean agreement for neither exceeded 59%, signifying room for improvement in the public's understanding of social responsibility.

Attribution theory suggests that certain SDOH may have resonated more with certain respondents because of the role of lived experience [19], [20]. In our analysis, older respondents, visible minorities, and people of lower income were generally more likely to attribute inequalities to the SDOH. Ruetter et al. have argued that these characteristics influence and reflect social standing, suggesting that differences in responses for these subgroups reflect their lived experience with the SDOH and with health inequalities [29]. For example, we found that visible minorities were more likely to understand the importance of social exclusion as a SDOH for low-income Ontarians, which may reflect their personal experience with racism, discrimination and social exclusion [30], [31]. Similarly, women were more likely to agree that “even though everyone in Ontario has access to medical care, the rich get more out of the health care system than the poor”, which, again, may reflect their experience with discrimination in the health care system and with the inappropriateness of some services [32], [33].

Attributions are influenced not just by personal experience, but also by one's socialization (i.e. the norms and values to which a person conforms to because of the groups with which they identify) [34]. In this study, political affiliation was associated with how respondents attributed inequalities, with left-leaning respondents being less willing to agree with the statement that attributed inequalities to individual lifestyle choices and more willing to agree with statements that criticized existing social structures around access to health care and food insecurity. Similarly, a more conservative socialization and ideology may equate to less willingness to attribute inequalities to the SDOH and to contextual factors [35]. Nevertheless, the reasons for the other sociodemographic differences that we observed are not clear and need to be explored, but may again relate to socialization. For example, men and visible minorities were more likely to agree with statements that blamed the poor for income-related health inequalities, and statements that were framed around the plight of the poor resonated less with older respondents. Whether based on a lack of lived experience or social norms, we have highlighted certain groups that may be harder to convince about the importance of the SDOH and accordingly of policies that reflect an understanding of these determinants.

We found a number of other Canadian studies that corroborate several of our findings. For example, Ruetter et al. have explored attributions of poverty and health, and similarly have shown that Canadians generally have a good understanding of the effects of poverty on health and quality of life [36], [37]. Canadians living in the province of Alberta were most likely to explain the relationship between poverty and poor health with drift (whereby people become poor after they get sick) or structural (whereby poor people are unhealthy because of living circumstances) hypotheses than with myth (whereby there is no link between poverty and health) or behavioural (where poor people exhibit behaviours that make them unhealthy) hypotheses [37]. Conservatism was the most consistent predictor of non-adherence to the structural hypothesis in one study [37]. Reutter et al. (2006) also conducted a telephone interview in two large Canadian cities on how the public attributes poverty [29]. Participants were generally most likely to attribute poverty to structural causes and least likely to attribute it to individual causes, and most knew that there was a relationship between poverty and health. Demographic variables explained a modest amount of variance in possible reasons for poverty. Men and people with less education were most likely to attribute poverty to laziness, suggesting less of an understanding of social determinants in general. In contrast, in the American literature, attributions of poverty that focus on the poor individual instead of on the failings of social structures tend to dominate [19], [23], [38], [39], which may reflect a more individualistic ethos or a more right-leaning political landscape in the U.S. [40]. Other relevant literature corroborates our finding that perceptions of the SDOH vary on the basis of political affiliation, with conservatives being more likely than liberals to disagree with the impact of the SDOH [41]–[43].

Our findings will be informative for the process of devising effective knowledge translation activities and messaging. We have shown that this sample of Ontarians was generally willing to accept messages framed around the plight of the poor or the privilege of the rich, with no strong preference for either. Messages that lay responsibility on the poor for inequalities seem likely to be less appealing to the public. Our results also suggest that, to be most effective, messages may need to be framed differently for different sociodemographic groups, such as older Ontarians, men or visible minorities [38], [43]. Essentially, knowledge translation and communication experts will have to work to counter both the “fundamental attribution error” and certain imposed norms. Although perceptions exist that the SDOH are not newsworthy and that the mainstream media are unlikely to provide coverage on the SDOH compared to other health determinants, the media have the potential to be an important partner in dissemination ventures [19], [29], [39], [44]. Media messaging can provide the public with exposure to health inequalities and can influence opinions about which SDOH-based policies should be implemented. Therefore, these perceptions of the media will have to be challenged by health equity advocates moving forward.

This study has several limitations. First, we used telephone sampling to obtain respondents. Telephone surveys exclude those without conventional landlines and accordingly, might under-sample people of lower socioeconomic position [18]. Future surveys should include cellular telephone users in order to maintain relevance. However, our sample had similar annual household income to the Ontario population as per the 2006 Census (29.8% with an annual household income of $40,000 or less versus 24.0% with an annual household income of less than $40,000) [18], [45]. As well, to combat any deviations from having a representative sample, our survey data were statistically weighted to be representative of Ontario adults in terms of composition by age and sex. Second, our response rate was low. However, this is typical of the response for random digit dialing surveys. To ensure representativeness, we constructed a quota sample whereby quotas for sex, age and regional representation were filled. Third, social desirability bias may have prevented respondents from verbally agreeing with statements that seemed to lay blame, even if they did in reality hold that viewpoint. Fourth, our constructs of blame, plight and privilege were not tested for their validity. However, their use has been supported by the health promotion and health inequities literature [19], [25], [26]. Finally, our chosen list of social determinants of health was not exhaustive. Using a broader set of determinants may have been more informative for policy makers. However, we wanted to limit the burden on survey respondents.

Conclusions

Although a majority of this sample of Ontarians were aware of income-related health inequalities [18], attributed inequalities to the SDOH, and were willing to accept messages that framed inequalities around the privilege of the rich or the plight of the poor, our results indicate that there is still significant room for improvement in their understanding of the root causes of inequalities. These findings will inform education campaigns, campaigns aimed at increasing public support for equity-focused public policy, and knowledge translation strategies. Our future work will focus on perceived solutions to income-related health inequalities among this sample of Ontarians, which will provide a more complete picture of beliefs and attitudes toward income-related health inequalities, and help to guide policymakers as they work toward building political will for equity-related public policy in the province.

Funding Statement

Data collection and analysis for this work was supported by the Population Health Improvement Research Network (PHIRN) of the Applied Health Research Network Initiative, Government of Ontario. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Krzyzanowska M, Barbera L, Elit L, Kwon J, Lofters A, et al.. (2009). Cancer. In: Arlene Bierman, editor. Project for an Ontario Women's Health Evidence-Based Report, Volume 1. Toronto.

- 2. Ng E, Wilkins R, Fung MF, Berthelot JM (2004) Cervical cancer mortality by neighbourhood income in urban Canada from 1971 to 1996. CMAJ 170 (10): 1545–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shields M (2004) Social anxiety disorder–beyond shyness. Health rep 15: Suppl45–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joseph KS, Liston RM, Dodds L, Dahlgren L, Allen AC (2007) Socioeconomic status and perinatal outcomes in a setting with universal access to essential health care services. CMAJ 177 (6): 583–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tjepkema M (2004) Alcohol and illicit drug dependence. Health rep 15: Suppl9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikkonen J, Raphael D (2010). Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management.

- 7. Marmot M (2005) Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 365 (9464): 1099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marmot M, Friel S (2008) Global health equity: evidence for action on the social determinants of health. J Epidemiol Community Health 62(12): 1095–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S (2008) Commission on Social Determinants of H. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 372(9650): 1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael D (2002). Poverty, Income Inequality, and health in Canada. Toronto: The CSJ Foundation for Research and Education.

- 11.Percy-Smith J (2000). Introduction: The contours of social exclusion. In: Percy-Smith J, editor. Policy Responses to Social Exclusion: Towards Inclusion? Buckingham, U.K.: Open University Press, p. 1–21.

- 12.Mitchell A, Shillington R (2002). Poverty, Inequality and Social Inclusion. Working Paper Series: Perspectives on Social Inclusion. Toronto: The Laidlaw Foundation.

- 13.WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Health Equity Impact Assessment - Ministry Programs. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (2013). Available: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/heia/.

- 15.Implementation of Section 54 of Quebec's Public Health Act. Institut National de Sante Publique du Quebec (2012). Available: http://www.ncchpp.ca/docs/Section54English042008.pdf.

- 16.Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2012). Health Equity Matters - IPPH Strategic Plan, 2009–2014. Available: htttp:///www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/40524.html#4_2.

- 17. Putland C, Baum FE, Ziersch AM (2011) From causes to solutions–insights from lay knowledge about health inequalities. BMC Public Health 11: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shankardass K, Lofters A, Kirst M, Quinonez C (2012) Public awareness of income-related health inequalities in Ontario, Canada. Int J Equity Health 11(1): 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niederdeppe J, Bu QL, Borah P, Kindig DA, Robert SA (2008) Message design strategies to raise public awareness of social determinants of health and population health disparities. Milbank Q 86(3): 481–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heider F (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: Wiley, p 336.

- 21.Mio JS (2003). On Teaching Multiculturalism: History, Models, and Content. In: Bernal G, Trimble JE, Burlew AK, Leong FTL, editors. Handbook of Racial and Ethnic Minority Psychology: Sage Publications.

- 22. Applebaum L (2001) The influence of perceived deservingness on policy decisions regarding aid to the poor. Polit Psychol 22(3): 419–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bullock H, Williams W, Limbert W (2003) Predicting support for welfare policies: The impact of attributions and beliefs about inequality. J Poverty 7(3): 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shirazi R, Biel A (2005) Internal-external causal attributions and perceived governmental responsibility for need provision: A 14-culture study. J Cross Cultl Psychol 36(1): 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stephens C (2010) Privilege and status in an unequal society: shifting the focus of health promotion research to include the maintenance of advantage. J Health Psychol 15(7): 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pease B (2009). The other side of social exclusion: Interrogating the role of the privileged in reproducing inequality. In: Taket A, Crisp BR, Nevill A, Lamaro G, Graham M, Barter-Godfrey S, editor. Theorising social exclusion. London: Routledge p. 37–46.

- 27.Social Environments and Health: Healthy Public Policy Concept Paper: Alberta Health Services 2011.

- 28.Teelucksingh C, Galabuzi G (2005). Working Precariously: The impact of race and immigrant status on employment opportunities and outcomes in Canada. The Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

- 29. Reutter LI, Veenstra G, Stewart MJ, Raphael D (2006) Public attributions for poverty in Canada. Can Rev Sociol Anthropol 43(1): 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Howland J, Sakellariou C (1993) Wage discrimination, occupational segregation and visible minorities in Canada. Appl Econ 25(11): 1413–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dion KL, Kawakami K (1996) Ethnicity and perceived discrimination in Toronto: Another look at the personal/group discrimination discrepancy. Can J Behav Sci 28(3): 203–13. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gomez D, Haas B, de Mestral C, Sharma S, Hsiao M, et al. (2012) Gender-associated differences in access to trauma center care: A population-based analysis. Surgery 152(2): 179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fowler RA, Sabur N, Li P, Juurlink DN, Pinto R, et al. (2007) Sex-and age-based differences in the delivery and outcomes of critical care. CMAJ 177(12): 1513–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guimond S, Begin G, Palmer DL (1989) Education and causal attributions: The development of "person-blame" and "system-blame" ideology. Soc Psychol Q 2(2): 126–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guimond S, Dambrun M, Michinov N, Duarte S (2003) Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognitions. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(4): 697–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reutter LI, Harrison MJ, Neufeld A (2002) Public support for poverty-related policies. Can J Public Health 93(4): 297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reutter L, Neufeld A, Harrison MJ (1999) Public perceptions of the relationship between poverty and health. Can J Public Health 90(1): 13–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aubrun A, Brown A, Grady J (2007). External Factors vs. Right Choices: Findings from Cognitive Elicitations and Media Analysis on Health Disparities and Inequities in Louisville, Kentucky: The Center for Health Equity.

- 39. Lopez GE, Gurin P, Nagda BA (1998) Education and understanding structural causes for group inequalities. Polit Psychol 19(2): 305–29. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. 3rd ed: McGraw-Hill.

- 41. Chirumbolo A, Areni A, Sensales G (2004) Need for cognitive closure and politics: Voting, political attitudes and attributional style. Int J Psychol 39(4): 245–53. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Robinson JW (2009) American poverty: Cause, beliefs and structured inequality legitimation. Sociol Spectr 29(4): 489–518. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gollust SE, Lantz PM, Ubel PA (2009) The polarizing effect of news media messages about the social determinants of health. Am J Public Health 99(12): 2160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Select Highlights on Public Views of the Determinants of Health (2005). Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Information.

- 45.(2006)Census of Canada: Canada and the Provinces (public-use microdata file). Using CHASS (distributor) Available: http://dc1.chass.utoronto.ca.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/census/ 2001_rp_all.html.