Improvements in the median CD4 count at antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation were modest during 2006–2011, with men increasingly more likely than women to initiate ART with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease. Those with >12-month gaps in care were more likely to initiate ART with advanced HIV disease.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, sub-Saharan Africa, antiretroviral treatment, advanced HIV disease

Abstract

Background. Timely antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation requires early diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with prompt enrollment and engagement in HIV care.

Methods. We examined programmatic data on 334 557 adults enrolling in HIV care, including 149 032 who initiated ART during 2006–2011 at 132 facilities in Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania. We examined trends in advanced HIV disease (CD4+ count <100 cells/μL or World Health Organization disease stage IV) and determinants of advanced HIV disease at ART initiation.

Results. Between 2006–2011, the median CD4+ count at ART initiation increased from 125 to 185 cells/μL an increase of 10 cells/year. Although the proportion of patients initiating ART with advanced HIV disease decreased from 42% to 29%, sex disparities widened. In 2011, the odds of advanced disease at ART initiation were higher among men (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3–1.5), those on tuberculosis treatment (AOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.0), and those with a ≥12 month gap in pre-ART care (AOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.6–2.6).

Conclusions. Intensified efforts are needed to identify and link HIV-infected individuals to care earlier and to retain them in continuous pre-ART care to facilitate more timely ART initiation.

Efforts to rapidly scale up access to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care and treatment have been successful at initiating large numbers of individuals on antiretroviral therapy (ART). The greatest increase has occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, home to 69% of the estimated 34 million people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide, where ART access has increased from 100 000 people on ART in 2003 to 6.2 million in 2011 [1]. Despite considerable success in expanding access to ART, most HIV-infected people in sub-Saharan Africa initiate ART in the advanced stages of HIV disease, resulting in substantial early mortality [2], more complicated and costly clinical management [3], lag in CD4+ cell–count response [4], and missed opportunities to prevent onward HIV transmission [5].

By 2011, approximately 56% of HIV-infected people in need of treatment in the sub-Saharan African region had accessed ART [1]. In recent years, most national HIV treatment programs in the region have adopted the expanded 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for ART eligibility of CD4+ count < 350 cells/µL (irrespective of WHO disease stage) or WHO disease stage 3 or 4 [6]. Although national guidelines are an important reference point, most individuals in sub-Saharan Africa have historically initiated ART at levels well below prevailing guideline thresholds [7]. Studies that have examined trends over time suggest that median CD4+ counts at ART initiation are increasing in most sub-Saharan African countries, but even in 2010 they remained below 200 cells/µL in most low- and middle-income countries [8–11]. The low CD4+ count at ART initiation may reflect, among other things, the need to prioritize the sickest individuals over those who are less sick [12].

The objectives of this study were to assess trends in the median CD4 count and proportion of HIV-infected individuals who initiated ART with advanced HIV disease between 2006 and 2011 in 4 sub-Saharan countries. We also examined individual-level factors associated with advanced HIV disease at ART initiation among patients starting ART in 2011.

METHODS

We examined longitudinal patient-level data from the pre-ART phase of care on 334 557 adults (aged ≥15 years) who enrolled in HIV care and treatment programs at 132 HIV care clinics in Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania between 2006 and 2011. The distribution of the number of facilities and persons enrolled in care by country was as follows: Kenya: 61 facilities, n = 82 318; Mozambique: 28 facilities, n = 187 992; Rwanda: 23 facilities, n = 24 378; and Tanzania: 20 facilities, n = 39 869. The clinics included are part of national ART programs and were supported during the study period by ICAP at Columbia University, a President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) implementing partner.

Data Sources

Patient information routinely collected at enrollment in HIV care and during each clinic visit was documented by clinicians on standard forms used nationally. Trained data clerks routinely abstracted relevant data from patients' medical charts for baseline and follow-up clinic visits and entered them into electronic databases. Data quality assessments were done every 6 months to assess for completeness and accuracy of data entry. Information was de-identified for analysis.

Definitions and Outcomes

ART initiation at the facilities was based on national guidelines within each country. Advanced HIV disease at enrollment in HIV care or ART initiation was defined as having a CD4+ count < 100 cells/μL or WHO disease stage 4. We defined “at enrollment” as any measurement within 1 month of enrollment into HIV care and “at ART initiation” as any measurement 3 months before or 1 month after ART initiation. In instances where CD4+ count or WHO disease stage were missing at ART initiation under the above definition, we used the highest WHO disease stage prior to initiation of ART and any prior CD4+ count < 100 cells/µL. A substantial proportion of patients still had missing information on CD4+ count and WHO disease stage at enrollment and ART initiation. These patients were included in our analyses using “missing/unknown” categories for CD4+ count, WHO disease stage, and advanced HIV disease at enrollment and at ART initiation, accordingly. Patients for whom there was no documentation of tuberculosis treatment were assumed not to be on treatment. Having a gap in pre-ART HIV care was defined as not having had a clinic visit for 12 or more months between enrollment and ART initiation.

Statistical Analysis

We examined characteristics of all patients receiving care at enrollment and at ART initiation. We then assessed the proportion of patients with advanced HIV disease at enrollment and at ART initiation in 2011 compared with 2006. Trends over time were examined in the proportion with advanced disease at enrollment into care and ART initiation, as well as the median CD4+ count at enrollment and ART initiation from 2006 to 2011 by sex. We also identified factors associated with ART initiation at advanced HIV disease in 2011, irrespective of year of enrollment in HIV care, using generalized linear models (GENMOD procedure in SAS with the log link function) to estimate the adjusted odds ratio (AOR), adjusting for age and other covariates and accounting for clustering of observations within clinics. In sensitivity analyses, multiple imputations for the marital status, point of entry, and ART eligibility variables were conducted to assess the impact of missing data on the final multivariate model. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to evaluate the extent to which each of the 4 countries individually influenced the overall results in the final model. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Ethical Considerations

The national ethics committees in each country, the Columbia University Medical Center institutional review board, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US PEPFAR Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator approved the use of data for this study.

RESULTS

Characteristics of All Adults Enrolled in Care

Sociodemographic characteristics of the 334 557 adults enrolled in care and the 149 032 who eventually initiated ART during 2006 and 2011 are presented in Table 1. At enrollment into care, two-thirds were women (10% of them documented as being pregnant). The overall median age was 33 years (interquartile range [IQR], 27–41) and nearly half were married or living with a partner. For ART patients, two-thirds were women (6% documented as being pregnant), the median age was 35 years (IQR, 29–43), and 46% were married or living with a partner.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Patients at Enrollment into Care From Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania Between 2006 and 2011

| Characteristic | All Patients at Enrollment into Care |

ART Patients at Enrollment into Care |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 334 557 | 100 | 149 032 | 100 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 110 771 | 33.1 | 52 926 | 35.5 |

| Women (not pregnant) | 200 390 | 59.9 | 90 015 | 60.4 |

| Women (pregnant) | 23 396 | 7.0 | 6091 | 4.1 |

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 33 (27, 41) | 35 (29, 43) | ||

| 15–25 | 70 954 | 21.2 | 20 162 | 13.5 |

| 26–35 | 128 856 | 38.5 | 56 878 | 38.2 |

| 36–45 | 83 033 | 24.8 | 43 961 | 29.5 |

| 46–55 | 37 161 | 11.1 | 20 466 | 13.7 |

| ≥56 | 14 553 | 4.4 | 7565 | 5.1 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 77 882 | 23.3 | 37 933 | 25.5 |

| Living with partner | 76 600 | 22.9 | 30 321 | 20.4 |

| Not in union | 74 543 | 22.3 | 32 312 | 21.7 |

| Divorced | 15 183 | 4.5 | 8233 | 5.5 |

| Widowed | 28 769 | 8.6 | 16 056 | 10.8 |

| Missing | 61 580 | 18.4 | 24 177 | 16.2 |

| Enrollment referral source | ||||

| VCT | 127 018 | 38.0 | 57 959 | 38.9 |

| PMTCT | 35 025 | 10.5 | 9398 | 6.3 |

| Tuberculosis clinic | 8892 | 2.7 | 4738 | 3.2 |

| PITC | 43 044 | 12.9 | 19 207 | 12.9 |

| Other | 96 015 | 28.7 | 47 491 | 31.9 |

| Unknown | 24 563 | 7.3 | 10 239 | 6.9 |

| Country | ||||

| Kenya (61 facilities) | 82 318 | 24.6 | 40 731 | 27.3 |

| Mozambique (28 facilities) | 187 992 | 56.2 | 75 808 | 50.9 |

| Rwanda (23 facilities) | 24 378 | 7.3 | 13 149 | 8.8 |

| Tanzania (20 facilities) | 39 869 | 11.9 | 19 344 | 13.0 |

| Year of enrollment | ||||

| 2006 | 53 545 | 16.0 | 25 934 | 17.4 |

| 2007 | 65 585 | 19.6 | 31 683 | 21.3 |

| 2008 | 64 190 | 19.2 | 29 164 | 19.6 |

| 2009 | 58 211 | 17.4 | 26 749 | 18.0 |

| 2010 | 51 529 | 15.4 | 22 762 | 15.3 |

| 2011 | 41 497 | 12.4 | 12 740 | 8.6 |

Number of sites = 132.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; IQR, interquartile range; PITC, provided initiated testing and counseling; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission; VCT, voluntary counseling and testing.

Clinical and Immunological Characteristics at Enrollment and ART Initiation

Of the 85% of patients with recorded information on CD4+ count and/or WHO disease stage at enrollment into care, 19% were classified as enrolling into care with advanced HIV disease (Table 2). Among the 53% of all patients and 65% of those who initiated ART with information on CD4+ count at enrollment, the median CD4+ counts were 259 cells/µL (IQR, 117–461) and 173 cells/µL (IQR, 80–285), respectively. Of the 74% of patients with WHO disease stage information at enrollment, 45% had WHO disease stage III or IV disease. At enrollment into care, 32% were ART eligible, while 17% had unknown eligibility (missing CD4+ count and/or WHO disease stage at enrollment). Among those who initiated ART during the observation period, more than half (54%) were ART eligible at enrollment.

Table 2.

Clinical and Immunological Characteristics at Enrollment into Care and Antiretroviral Treatment Initiation of Patients From Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania Between 2006 and 2011

| Characteristic | All Patients at Enrollment into Care |

ART Patients at Enrollment into Care |

ART Patients at ART Initiation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 334 557 | 100 | 149 032 | 100 | 149 032 | 100 |

| Advanced human immunodeficiency virus diseasea | ||||||

| Data available | 284 456 | 85.0 | 138 469 | 92.9 | 142 721 | 95.8 |

| Yes | 55 245 | 19.4 | 39 683 | 28.7 | 50 179 | 35.2 |

| No | 229 211 | 80.6 | 98 786 | 71.3 | 92 542 | 64.8 |

| CD4+ count, cells/µL | ||||||

| Data available | 176 109 | 52.6 | 97 200 | 65.2 | 106 067 | 71.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 259 (117, 461) | 173 (80, 285) | 155 (72, 238) | |||

| Clinical WHO disease stage | ||||||

| Data available | 247 822 | 74.1 | 121 617 | 81.6 | 134 830 | 90.5 |

| Stage I | 71 563 | 28.9 | 23 395 | 19.2 | 22 436 | 16.6 |

| Stage II | 64 228 | 25.9 | 30 983 | 25.5 | 32 631 | 24.2 |

| Stage III | 90 868 | 36.7 | 53 628 | 44.1 | 61 477 | 45.6 |

| Stage IV | 21 163 | 8.5 | 13 611 | 11.2 | 18 286 | 13.6 |

| ART eligibility at enrollmentb | ||||||

| Not eligible | 171 575 | 51.3 | 55 191 | 37.0 | … | … |

| Eligible | 107 766 | 32.2 | 80 825 | 54.2 | … | … |

| Unknown | 55 216 | 16.5 | 13 016 | 8.7 | … | … |

| Documented tuberculosis treatment | ||||||

| Yes | 13 195 | 3.9 | 8266 | 5.6 | 4336 | 2.9 |

| No | 321 362 | 96.1 | 140 766 | 94.4 | 144 696 | 97 |

Number of sites = 132.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; IQR, interquartile range; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Advanced disease was defined as having a CD4+ count < 100 cells/μL or WHO disease stage IV within 1 month of enrollment into HIV care or 3 months before or 1 month after ART initiation.

b According to the country national guidelines.

Among those who initiated ART, 96% had information on CD4+ count and/or WHO disease stage at ART initiation, of those 35% had advanced HIV disease. Among the 71% with CD4+ count information, the median CD4+ count was 155 cells/µL (IQR, 72–238). Of the 91% with information on WHO disease stage at ART initiation, 59% had WHO stage III or IV disease. Finally, 3% were documented to be on tuberculosis treatment at ART initiation.

Change Over Time in Median CD4+ Counts and Proportion Enrolling in Care and Initiating ART With Advanced HIV Disease

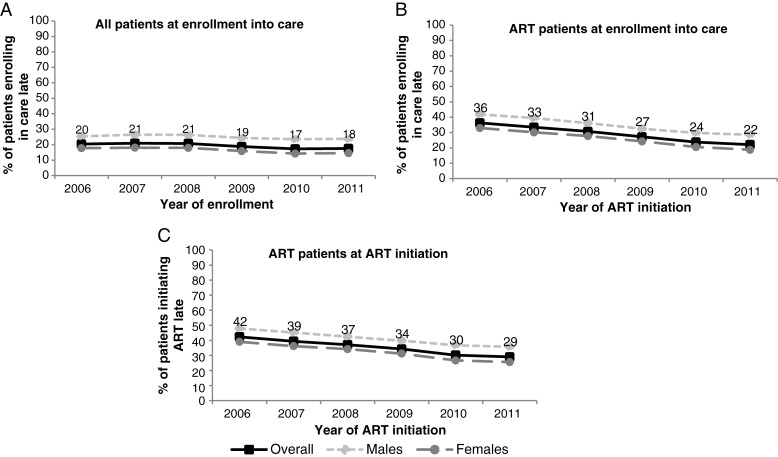

The proportion of patients enrolling in care with advanced HIV disease decreased from 20% to 18% (P trend < .001) from 2006 to 2011 (Figure 1A), while among patients who initiated ART, the proportion enrolling in care with advanced HIV disease decreased from 36% to 22% (P trend < .001; Figure 1B). The proportion of patients who initiated ART with advanced HIV disease decreased from 42% to 29% (P trend < .001) from 2006 to 2011; decreases were observed among both males and females (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease at enrollment among all patients (A), at enrollment among those that initiated antiretroviral treatment (ART) (B), and at ART initiation among patients initiating ART by sex (C) (132 sites). Excluding patients who did not have enough information about their status at enrollment and ART initiation (ie, no CD4+ count or no World Health Organization disease stage).

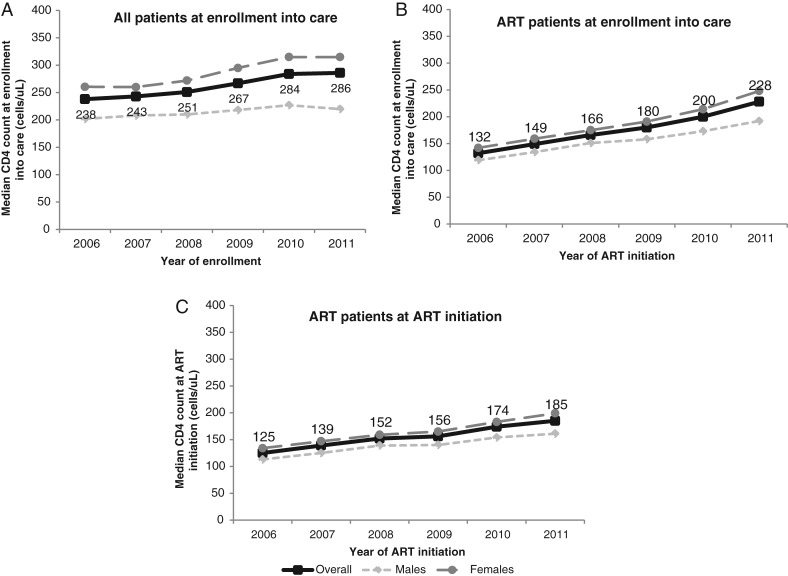

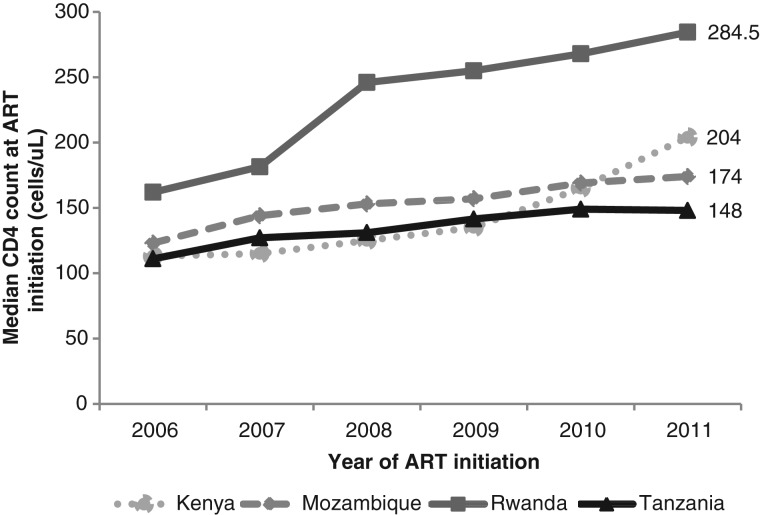

The proportion of patients with recorded CD4+ counts at enrollment increased from 46% in 2006 to 55% in 2011. Among all patients, the median CD4+ count at enrollment in care increased from 238 cells/μL (IQR, 106–436) in 2006 to 286 cells/μL (IQR, 127–482) in 2011 (P < .001; Figure 2A) and from 132 cells/μL (IQR, 61–214) to 228 cells/μL (IQR, 107–354) among patients who eventually initiated ART (Figure 2B). The median CD4+ count increased over time for both women and men and was higher among women than among men. Of patients initiating ART, there was an increase in median CD4+ count at ART initiation from 125 cells/μL (IQR, 57–202) to 185 cells/μL (IQR, 86–279; P < .001; an increase of 10 cells per year; Figure 2C). The proportion with nonmissing CD4+ count information at ART initiation did not change appreciably over time (70% in 2006 and 68% in 2011). Differences were observed in the trends of median CD4+ count at ART initiation, with Kenya and Rwanda experiencing the largest increases over time (Figure 3). In 2011, the median CD4+ count at ART initiation was significantly different by country (P value < .001).

Figure 2.

Median CD4+ count at enrollment into care by sex among all patients at enrollment (A), at enrollment among those who initiated antiretroviral therapy (ART) (B), and at ART initiation among patients initiating ART (C).

Figure 3.

Median CD4+ count at antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation by country.

There was a significant decrease in the overall proportion of patients enrolling in care with advanced HIV disease between 2006 and 2011 (20% vs 17%; P < .05), as well as among patients aged 15–25 years (11% vs 15%) and 26–35 years (17% vs 21%), those living with a partner (14% vs 19%), those not in union (18% vs 23%), those in Mozambique (21% vs 17%), and those in Tanzania (22% vs 33%). Table 3 presents the differences in the proportion of patients who initiated ART with advanced HIV disease between 2006 and 2011 for various sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at ART initiation. There was a significant decrease in the proportion initiating ART with advanced HIV disease between 2011 compared with 2006 overall (42% vs 29%), as well as across the majority of sociodemographic and clinical categories. In 2011, the IQR for the proportion initiating ART with advanced HIV disease was 19%–35% across the 132 sites.

Table 3.

Differences in the Proportion of Patients Initiating Antiretroviral Treatment With Advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease in 2006 and 2011 by Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristicsa

| Characteristic | 2006 |

2011 |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % Advanced HIV Disease | N | % Advanced HIV Disease | ||

| Total | 15 669 | 42.4 | 20 366 | 29.1 | <.0001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 5854 | 47.9 | 6924 | 35.7 | <.0001 |

| Women (not pregnant) | 9522 | 39.5 | 12 195 | 26.6 | <.0001 |

| Women (pregnant) | 293 | 24.2 | 1247 | 16.2 | .07 |

| Age, y | |||||

| 15–25 | 1589 | 40.7 | 3262 | 24.7 | <.0001 |

| 26–35 | 5840 | 43.9 | 7769 | 29.5 | <.0001 |

| 36–45 | 5151 | 43.7 | 5567 | 30.6 | <.0001 |

| 46–55 | 2316 | 39.4 | 2697 | 30.0 | <.0001 |

| ≥56 | 773 | 34.4 | 1071 | 28.7 | .01 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 3634 | 39.6 | 5251 | 27.4 | <.0001 |

| Living with partner | 2409 | 44.3 | 4854 | 26.8 | <.0001 |

| Not in union | 3151 | 46.5 | 4650 | 31.0 | <.0001 |

| Divorced | 604 | 48.3 | 1324 | 33.1 | <.0001 |

| Widowed | 1949 | 36.2 | 1857 | 27.4 | .0002 |

| Missing | 3922 | 42.6 | 2430 | 32.4 | .013 |

| Enrollment point of entry | |||||

| VCT | 7055 | 40.5 | 7563 | 29.3 | <.0001 |

| PMTCT | 708 | 21.6 | 1757 | 15.9 | .06 |

| Tuberculosis/HIV | 594 | 34.3 | 558 | 33.5 | .82 |

| PITC | 2231 | 47.7 | 2564 | 37.7 | .008 |

| Other | 3958 | 46.2 | 6669 | 28.2 | <.0001 |

| Unknown | 1123 | 47.6 | 1255 | 31.0 | <.0001 |

| Country | |||||

| Kenya | 4279 | 37.2 | 5102 | 24.6 | <.0001 |

| Mozambique | 7128 | 46.6 | 10 844 | 29.4 | <.0001 |

| Rwanda | 2420 | 29.4 | 1387 | 14.2 | <.0001 |

| Tanzania | 1842 | 55.2 | 3033 | 41.9 | .007 |

| CD4+ count at enrollment into care, cells/µL | |||||

| CD4+ <100 | 4098 | 100.0 | 3262 | 100.0 | … |

| 100 ≤ CD4 + <200 | 3486 | 10.1 | 2856 | 10.8 | .67 |

| 200 ≤ CD4 + <350 | 2307 | 10.7 | 4095 | 7.7 | .01 |

| CD4 + ≥350 | 693 | 23.8 | 3538 | 13.6 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 5085 | 35.0 | 6615 | 23.5 | <.0001 |

| Clinical WHO disease stage at enrollment into care | |||||

| Stage I | 1336 | 22.2 | 5218 | 14.7 | <.0001 |

| Stage II | 2775 | 28.8 | 4950 | 23.9 | .017 |

| Stage III | 7208 | 34.5 | 5690 | 28.5 | .01 |

| Stage IV | 1927 | 100.0 | 1482 | 100.0 | … |

| Missing | 2423 | 46.7 | 3026 | 28.6 | <.0001 |

| Advanced HIV disease at enrollment | |||||

| Yes | 5537 | 100.0 | 4383 | 100.0 | … |

| No | 9673 | 9.1 | 15 338 | 8.9 | .84 |

| Unknown | 459 | 47.7 | 645 | 25.9 | <.0001 |

| Documented tuberculosis treatment at enrollment/ART initiation | |||||

| Yes | 307 | 38.8 | 512 | 41.4 | .56 |

| No/unknown | 15 362 | 42.4 | 19 854 | 28.7 | <.0001 |

Number of sites = 132.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PITC, provided initiated testing and counseling; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission; VCT, voluntary counseling and testing; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Adjusted by age and side-clustered effect.

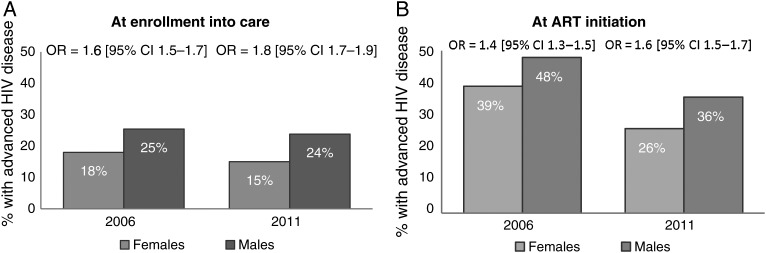

However, despite the decrease in the proportion of patients enrolling and those initiating ART with advanced HIV disease among both genders (Figure 1A and 1C), men remained at higher risk compared with women, and this disparity appears to be widening with time. Specifically, there was an increase in the odds of advanced HIV disease at enrollment into care for males vs females from 1.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5–1.7) in 2006 to 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7–1.9) in 2011, while advanced HIV disease at ART initiation increased from 1.4 (95% CI, 1.3–1.5) in 2006 to 1.6 (95% CI, 1.5–1.7) in 2011 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Odds ratios of advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease for males vs females at enrollment into care (A) and antiretroviral therapy initiation (B) in 2006 and 2011. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

Factors Associated With ART Initiation Among Patients With Advanced HIV Disease Initiating ART in 2011

In the multivariate model (Table 4), higher odds of initiating ART at advanced disease were observed among the following: (a) men compared with nonpregnant women (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3–1.5), (b) those enrolling in care through provider-initiated testing and counseling (AOR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.4), (c) those in Mozambique and Tanzania (AOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.7; AOR, 2.8 95% CI, 2.2–3.6) compared with those in Kenya, (d) those documented to be on tuberculosis treatment at ART initiation (AOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.0) compared with those not on tuberculosis treatment, and (e) those who had a ≥12 month gap in pre-ART care (AOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.6–2.6) compared with those who were engaged in care. Significantly lower odds of ART initiation with advanced HIV disease were observed among patients aged 46–55 and ≥56 years compared with those aged 26–35 years (AOR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.73–0.94; AOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71–0.99, respectively), (b) those married or living with a partner compared with those single (AOR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77–0.94; AOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81–0.97, respectively), (c) those enrolling in care through PMTCT services (AOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.55–0.80); (d) those in Rwanda compared with those in Kenya (AOR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38–0.58), and (e) those not eligible for ART or with unknown eligibility at enrollment into care compared to those eligible (AOR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.10–0.15; AOR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.17–0.24, respectively).

Table 4.

Odds Ratio of Advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease at Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Initiation Among Persons Initiating ART in 2011 Adjusting for Site-Clustering Effect

| Characteristic | N | % Advanced HIV Disease | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 132 sites) | 20 366 | 29.1 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 6924 | 35.7 | 1.6 | (1.5–1.7) | 1.4 | (1.3–1.5) |

| Women (not pregnant at ART initiation) | 12 195 | 26.6 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Women (pregnant at ART initiation) | 1247 | 16.2 | 0.53 | (0.35–0.81) | 0.72 | (0.48–1.1) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 15–25 | 3262 | 24.7 | 0.84 | (0.76–0.94) | 0.90 | (0.80–1.01) |

| 26–35 | 7769 | 29.5 | Ref | Ref | 1 | |

| 36–45 | 5567 | 30.6 | 1.0 | (0.94–1.1) | 0.92 | (0.84–1.01) |

| 46–55 | 2697 | 30.0 | 0.95 | (0.85–1.1) | 0.83 | (0.73–0.94) |

| ≥56 | 1071 | 28.7 | 0.91 | (0.78–1.1) | 0.84 | (0.71–0.99) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not in union | 5251 | 27.4 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Married | 4854 | 26.8 | 0.79 | (0.72–0.87) | 0.85 | (0.77–0.94) |

| Living with partner | 4650 | 31.0 | 0.85 | (0.79–0.93) | 0.89 | (0.81–0.97) |

| Divorced | 1324 | 33.1 | 0.95 | (0.82–1.1) | 0.92 | (0.80–1.1) |

| Widowed | 1857 | 27.4 | 0.84 | (0.74–0.95) | 0.94 | (0.83–1.1) |

| Missing | 2430 | 32.4 | 0.93 | (0.81–1.1) | 1.0 | (0.93–1.2) |

| Enrollment point of entry | ||||||

| VCT | 7563 | 29.3 | Ref | Ref | ||

| PMTCT | 1757 | 15.9 | 0.50 | (0.40–0.63) | 0.66 | (0.55–0.80) |

| Tuberculosis/HIV | 558 | 33.5 | 1.38 | (1.05–1.82) | 1.1 | (0.84–1.5) |

| PITC | 2564 | 37.7 | 1.49 | (1.31–1.68) | 1.2 | (1.1–1.4) |

| Other | 6669 | 28.2 | 0.98 | (0.84–1.1) | 0.98 | (0.89–1.1) |

| Unknown | 1255 | 31.0 | 1.00 | (0.84–1.3) | 0.99 | (0.85–1.2) |

| Country | ||||||

| Kenya | 5102 | 24.6 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Mozambique | 10 844 | 29.4 | 1.4 | (1.2–1.7) | 1.4 | (1.2–1.7) |

| Rwanda | 1387 | 14.2 | 0.50 | (0.41–0.61) | 0.47 | (0.38–0.58) |

| Tanzania | 3033 | 41.9 | 2.1 | (1.6–2.8) | 2.8 | (2.2–3.6) |

| ART eligibility at enrollmenta | ||||||

| Not eligible | 10 148 | 11.3 | 0.12 | (0.10–0.15) | 0.12 | (0.10–0.15) |

| Eligible | 9046 | 50.6 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Unknown | 1172 | 17.1 | 0.20 | (0.16–0.25) | 0.20 | (0.17–0.24) |

| Documented tuberculosis treatment at ART initiation | ||||||

| Yes | 512 | 41.4 | 2.1 | (1.7–2.6) | 1.6 | (1.3–2.0) |

| No/unknown | 19 854 | 28.7 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥12 mo gap in pre-ART care | ||||||

| No | 3644 | 12.5 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1149 | 25 | 2.2 | (1.8–2.8) | 2.0 | (1.6–2.6) |

| Initiated ART during first year after enrollment | 15 573 | 33.2 | 3.4 | (2.7–4.3) | 1.1 | (0.90–1.4) |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio; PITC, provided initiated testing and counseling; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission; VCT, voluntary counseling and testing.

a According to the country national guidelines.

Statistically significant OR have been bolded.

Results of sensitivity analyses using multiple imputations of missing data were highly consistent in terms of the direction, magnitude, and significance of associations to those presented in Table 4. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted excluding each of the 4 countries from the final model and including those with missing CD4 count and WHO disease stage as initiating ART at advanced HIV disease or not. Results from these models were also consistent with those in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed a substantial decrease in the proportion of patients who initiated ART with advanced disease between 2006 and 2011 at 132 clinical care facilities that provide care in Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania (from 42% to 29%). That the proportion of patients initiating ART in the advanced stages of HIV decreased, with little change in the proportion of those with advanced disease at enrollment (from 20% to 18%), suggests that many clinics and settings included in our analyses are making progress in treating the sickest individuals in their catchment areas, but that intensified and targeted efforts aimed at earlier diagnosis and linkage to care are needed. The median CD4+ count increased over time both at enrollment into care as well as at ART initiation (from 238 to 286 cells/μL and from 125 to 185 cells/μL, respectively, or about 10 cells/year). While the increase is encouraging, the rate of increase observed in our sample is discouragingly slow, such that it would be more than 15 years before the median CD4 count at ART initiation reached 350 cells/µL (ie, when only half of patients initiating ART would do so at the current recommended CD4 threshold). Of concern is that the well-documented male–female disparity in the risk of initiating ART with advanced HIV disease in the region appears to be worsening with time. Finally, those who experience a ≥12 month gap in pre-ART care were more likely to initiate ART with advanced HIV disease, independent of other factors. These findings have clear implications for program implementers in the sub-Saharan African region.

Among patients who initiated ART between 2006 and 2011, 29% had advanced HIV disease at enrollment in care and 35% at ART initiation, suggesting that most of those who initiated ART at advanced HIV disease did so because they had enrolled in care with advanced HIV disease. Enrollment into care with advanced HIV could be due to late diagnosis or delayed linkage to care once diagnosed [7, 13–15]. Given the moderate decline in the proportion enrolling in HIV care with advanced disease, our results highlight the urgent need to redouble efforts aimed at expanding HIV testing coupled with timely linkage to care, with the aim of promoting earlier ART initiation. The substantial variability across facilities in the proportion initiating ART with advanced HIV disease underscores the possibility that important and potentially modifiable determinants of this outcome operate beyond the individual level, such as the clinic and contextual levels. This has been suggested by our team [7, 9, 10] as well as others [16], and future studies should continue to elucidate higher-level effects that could suggest avenues for clinic- and catchment area–level interventions that promote earlier ART initiation.

The increase in the median CD4 count at ART initiation over time is likely due to progress in treating the sickest individuals in the clinic catchment areas and, in some cases (eg, Rwanda), expansion of national CD4-based ART eligibility thresholds. However, even in 2011, men in our sample were more likely than women to enroll in care and initiate ART with advanced HIV disease, as previously described [4, 9, 17]. Importantly, despite declines in the proportion initiating ART with advanced HIV disease for both genders, the male–female disparity appears to be worsening with time. The reasons likely include that HIV-positive women may be more likely to engage in health-seeking behaviors resulting in HIV diagnosis and care linkage [18], as well as the increased PMTCT scale-up and improved linkages between PMTCT and HIV care for women [19, 20]. In our sample, the proportion of patients who enrolled in care through PMTCT services doubled from 7% in 2006 to 14% in 2011, and those enrolling in care through PMTCT services had lower odds of initiating ART with advanced HIV disease.

Broad differences in the median CD4 count and trends over time were observed among sites in different countries, with a rapid increase in the median CD4 count at ART initiation at sites in Rwanda compared with sites in other countries. Several reasons could explain why patients at sites from Rwanda had uniformly higher median CD4 counts at ART initiation, including the implementation of a higher CD4 count threshold for ART eligibility in the national ART guidelines, lower patient caseload, higher provider to patient ratios, and early decentralization of services. Another recent study indicated that patients in Rwanda has the second highest mean CD4 count at ART initiation in the world (with the United States having the highest) [11].

In multivariate models using longitudinal data from the pre-ART phase of care, we observed that patients who had a gap of ≥12 months in pre-ART care had twice the odds of initiating ART with advanced HIV disease. A systematic review of retention in HIV care prior to ART initiation in sub-Saharan Africa suggests that less than one-third of patients who test positive for HIV and are not eligible for ART at enrollment in care are retained continuously in care [21]. Providing incentives during HIV care, such as free cotrimoxazole, was shown in a small study to increase retention of such patients [22]. In an observational study, point-of-care CD4+ testing has been shown to reduce the median time between enrollment and ART initiation [23] and could therefore be an effective strategy to reduce pretreatment loss to follow-up and promote more timely ART initiation.

The strengths of this study include the incorporation of longitudinal data from the pre-ART phase of care and use of data derived from routine programs in a large number of HIV care and treatment clinics from a variety of facility types and settings in different regions of Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania. However, our results should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. The clinics included in this analysis, while part of national ART programs, are likely not representative of all clinics that provide HIV care and treatment in each of the 4 countries. The lack of interview data and information on the timing of HIV diagnosis and ART eligibility status at HIV diagnosis restricted our capacity to fully evaluate all the pathways leading to ART initiation when in the advanced stages of HIV disease. However, others are beginning to elucidate the potential underlying causes of late HIV presentation in the region, as in a recent study by Drain et al [13]. Finally, there were substantial missing data in our study, particularly CD4+ cell counts, both at enrollment in HIV care and at ART initiation, highlighting the importance of complete assessment of patients and documentation of clinical and laboratory findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, interventions are needed to diagnose HIV earlier, promote prompt linkage to HIV care, effectively enroll such individuals in continuous care and monitor them for ART eligibility, and, once eligible, to initiate them on ART in a timely manner. Without such efforts to promote earlier treatment initiation, the full potential for impact of HIV programmatic scale-up in the sub-Saharan African region may be diminished over the long term, in terms of both individual benefits and public health benefits of preventing onward HIV transmission.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank all patients and staff at the HIV care and treatment facilities included in this analysis. We acknowledge the efforts of the in-country ICAP staff and clinic staff who collected the data used for this analysis. We also thank the members of the Optimal Model Steering Committees in Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Tanzania.

Financial support. This work was supported by the PEPFAR and by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Optimal Models Collaboration (grant number 5U2GPS001537-03) and by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number R01MH089831). All clinics included in this analysis received support from ICAP through funding from the PEPFAR.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.UNAIDS/WHO. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012. 2012. (WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-92-9173-592-1) Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf .

- 2.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krentz HB, Auld MC, Gill MJ. The high cost of medical care for patients who present late (CD4 <200 cells/microL) with HIV infection. HIV Med. 2004;5:93–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nash D, Katyal M, Brinkhof MW, et al. Long-term immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. AIDS. 2008;22:2291–302. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283121ca9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: towards universal access: recommendations for a public health approach. 2010. (WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978 92 4 159976 4) Retrieved at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf . [PubMed]

- 7.Lahuerta M, Frances U, Hoffman S, et al. The problem of late ART initiation in sub-Saharan Africa: a transient aspect of scale-up or a long-term phenomenon? J Health Care Poor Undeserved. 2013;24:359–83. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keiser O, Anastos K, Schechter M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings 1996 to 2006: patient characteristics, treatment regimens and monitoring in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:870–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahuerta M, Lima J, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, et al. Factors associated with late antiretroviral therapy initiation among adults in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nash D, Wu Y, Elul B, Hoos D, El Sadr W. Program and contextual-level determinants of low median CD4+ cell count in cohorts of persons initiating ART in 8 sub-Saharan African countries. AIDS. 2011;25:1523–33. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834811b2. (AIDS) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The IeDEA and ART cohort collaborations. Immunodeficiency at the start of combination antiretroviral therapy in low, middle and high-income countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a39979. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a39979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Sadr WM, Hoos D. The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief—is the emergency over? N Engl J Med. 2008;359:553–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0803762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drain PK, Losina E, Parker G, et al. Risk factors for late-stage HIV disease presentation at initial HIV diagnosis in Durban, South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P, et al. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakigozi G, Makumbi F, Reynolds S, et al. Non-enrollment for free community HIV care: findings from a population-based study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2011;23:764–70. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndawinz JD, Chaix B, Koulla-Shiro S, et al. Factors associated with late antiretroviral therapy initiation in Cameroon: a representative multilevel analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1388–99. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braitstein P, Boulle A, Nash D, et al. Gender and the use of antiretroviral treatment in resource-constrained settings: findings from a multicenter collaboration. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:47–55. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:616–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taha TE. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in sub-Saharan Africa: past, present and future challenges. Life Sci. 2010;88:917–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi BH, Adler MR, Bolu O, et al. Progress, challenges, and new opportunities for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV under the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(Suppl 3):S78–87. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825f3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohler PK, Chung MH, McGrath CJ, Benki-Nugent SF, Thiga JW, John-Stewart GC. Implementation of free cotrimoxazole prophylaxis improves clinic retention among antiretroviral therapy-ineligible clients in Kenya. AIDS. 2011;25:1657–61. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834957fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jani IV, Sitoe NE, Alfai ER, et al. Effect of point-of-care CD4 cell count tests on retention of patients and rates of antiretroviral therapy initiation in primary health clinics: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1572–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]