Abstract

Left ventricular assist device (LVAD) is a good treatment option for the patients ineligible for cardiac transplantation. Several studies have demonstrated that a ventricular assist device improves the quality of life and prognosis of the patients with end-stage heart failure. A 75-yr-old man debilitated with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III-IV due to severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction received LVAD implantation as a destination therapy. The patient was discharged with improved functional status (NYHA functional class II) after appropriate cardiac rehabilitation and education about how to manage the device and potential emergency situations. This is the first case of successful continuous-flow LVAD implantation as a destination therapy in Korea.

Keywords: Heart Failure, Mechanical Circulatory Support, Heart-Assist Device, HeartMate II

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac transplantation is a good treatment option for the patients with end-stage heart failure. Nevertheless, only a limited number of patients are privileged to have cardiac transplantation due to significant organ shortage. Meanwhile, left ventricular assist device (LVAD) demonstrated to improve the functional capacities and prognosis of end-stage heart failure patients compared to optimal medical management (1-3). Furthermore, the second generation continuous-flow LVAD has shown better results to increase survival of end-stage heart failure patients than the first generation LVAD with pulsatile-flow (4). We describe here the first case of continuous-flow LVAD implantation as a destination therapy in Korea and the echocardiographic assessment before and after the procedure.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 75-yr-old male with a prosthetic aortic valve complained of his ongoing exacerbation of dyspnea which started at December, 2010. He had visited regularly the outpatient clinic of cardiology in our institution since June, 2002. Twelve years ago, he had received aortic valve replacement with Medtronic-Hall valve (24 mm) due to severe rheumatic aortic regurgitation. However, in spite of good prosthetic valve function and medical treatment including angiotensin receptor blocker and beta-blocker, his left ventricular (LV) systolic function and LV dilation gradually deteriorated. In consequence, he was suffered from dyspnea of New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III to IV. He had no history of hypertension or diabetes mellitus, but had atrial fibrillation. Laboratory findings were within normal range except mild azotemia (serum creatinine 1.75 mg/dL) and prolonged prothrombin time (INR 1.97). Because his old age and functional deconditioning caused by long-term illness prevented him from being a good candidate for heart transplantation, he was recommended for LVAD implant as a destination therapy. The level of LVAD risk was medium with score 12 by Lietz (5) and high with score 2.95 by HeartMate II Risk Score (6). However, because the patient's prolonged INR was caused by anticoagulation for prosthetic valve rather than pathologic coagulopathy, his actual risk of LVAD implant was thought to be lower than the calculated risk score.

On preoperative evaluation, he had insignificant stenosis in the coronary arteries in coronary angiography. In transthoracic echocardiography, LV dimensions were dilated (70/69 mm at diastole/systole), and LV ejection fraction by Simpson's method was only 20%. But, the right ventricular (RV) function was relatively preserved and RV cavity size was normal [tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)=14 mm, s'=0.07 m/sec, RV fractional area change (RVFAC)=60%, and RV diastolic dimension base/mid=33/17 mm]. Mild mitral regurgitation (MR) and moderate tricuspid regurgitation (TR) were observed. Inferior vena cava (IVC) was dilated without plethora, and RV systolic pressure by TR peak velocity was 39 mmHg. The prosthetic valve continued to function well with physiologic aortic regurgitation; Vmax=1.9 m/sec, mean pressure gradient=7.7 mmHg, effective aortic valve area by continuity equation=2.1 cm2. Although the function of prosthetic aortic valve was good, the closure of aortic valve was determined after the surgical consultation in concern of possible secondary pump flow upregulation by physiologic aortic regurgitation.

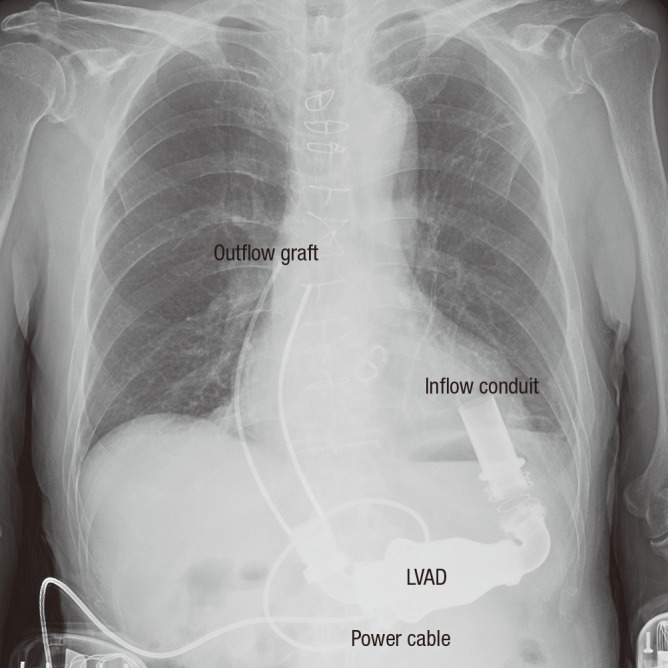

After informed consent was obtained from the patient and his family, LVAD implantation with HeartMate II (Thoratec, Pleasanton, CA, USA) proceeded. For the surgery of LVAD implantation, he admitted to our hospital on 11th, August, 2012. And the implantation of LVAD was performed on 17th, August, 2012. To insert a propulsion pump in upper abdomen, a midline sternotomy was extended to the upper abdomen. An outflow graft was connected to the aorta with end to side anastomosis. After the removal of some chordae that could cause turbulent flow in the LV chamber, the inflow conduit was inserted at LV apical position. The mechanical prosthetic aortic valve was closed with two round 24 mm and 22 mm-sized Teflon felts. During the procedure, we checked the presence of patent foramen ovale (PFO) with transesophageal echocardiography by injecting agitated saline via a central venous catheter, but microbubbles were not observed in the left side of the heart. We additionally performed cryoablation at cavo-tricuspid isthmus for 2 min and 45 sec and resected left atrial appendage. The postoperative chest X-ray clearly shows the positions of inflow conduit, LVAD as propulsion pump, outflow cannula and power cable connected to extracorporeal controller (Fig. 1).

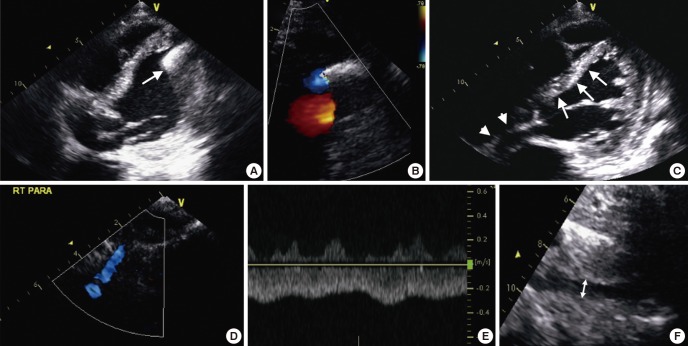

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray after LVAD implantation. (The illustration of outflow graft is added on the patient's chest radiography)

On the day following LVAD implantation, he was extubated in a stable hemodynamic condition. We checked the patient's volume status and the function of LVAD with daily bed-side echocardiographic assessment (Fig. 2). We manipulated the revolutions per minutes (rpm) of LVAD in the range of 8,800-9,200 to maintain midline position of interatrial septum (IAS) and interventricular septum (IVS). The size of IVC was monitored to assess his volume status. For example, at postoperative day (POD) 10, we had to decrease rpm from 8,800 to 8,400 to maintain the mid-position of IAS and IVS, because the septum deviated to the left side at a higher rpm. However, at the same time, the IVC was observed to be collapsed with a diameter of 0.7 cm. So, after enough volume replacement for 2 days, we could elevate rpm to the level of 8,800 again, monitoring the echocardiographic parameters.

Fig. 2.

Checkpoint in echocardiographic assessment after LVAD implantation. (A, B) The axis and laminar flow of inflow conduit in modified apical-4-chamber view, (C) The position of interventricular septum (IVS) and interatrial septum (IAS), (D, E) The flow of inflow cannula in right parasternal view, and (F) IVC diameter in subcostal view.

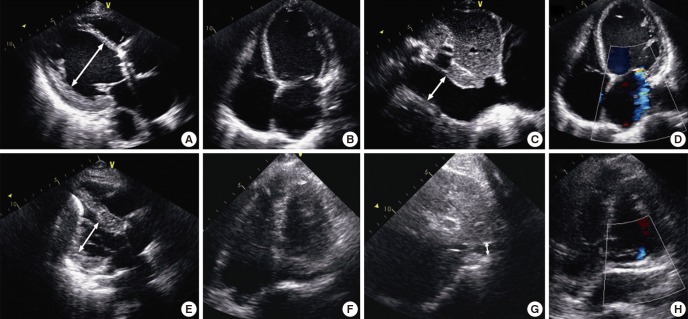

During the hospital stay, he acquired aspiration pneumonia several days after the surgery. As a result, he stayed in intensive care unit until postoperative day 11. He could not participate in the cardiac rehabilitation program until he recovered fully from aspiration pneumonia. During the rehabilitative period, he and his family members were properly educated about how to manage the device and potential emergency situations. Eventually, the patient was discharged in a condition of NYHA functional class II with LVAD rpm 9,200, 4 months after the implantation. Additionally, obviously improved hemodynamic change by decreased LV filling pressure was observed in follow-up echocardiography (Fig. 3). LV dimension and IVC diameter were decreased, and IVS and IAS lay in midline position instead of deviating to the right side due to increased LV filling pressure, and functional MR was significantly decreased.

Fig. 3.

Hemodynamic change after LVAD implantation. Before the procedure, (A) Left ventricle was severely dilated, (B) IVS and IAS were deviated to right side due to increased left ventricular filling pressure, (C) IVC was dilated, (D) Functional mitral regurgitation of mild degree was observed. After LVAD implantation, (E) LV dimension and (G) IVC diameter were decreased, (F) IVS and IAS appeared in midline position, and (H) Functional MR was significantly decreased.

The patient maintains NYHA functional class II currently over 240 days after the LVAD implant.

DISCUSSION

In Korea, there has been a successful case of pulsatile-flow LVAD implantation as a bridge therapy before heart transplantation (7). However, the presenting case was the first successful continuous-flow LVAD implantation as a destination therapy in Korea. We implanted HeartMate II successfully in a patient with end-stage heart failure ineligible for heat transplantation. The evidence of LVAD implantation benefits as a destination therapy was proved by randomized controlled trial (1, 3). Hence, LVAD should be another option for end-stage heart failure patients who cannot be candidates for cardiac transplantation.

For successful LVAD implantation, not only LV systolic function but also the presence of significant aortic regurgitation or intracardiac shunt should be evaluated before the insertion. Left to right shunt or aortic regurgitation greater than a mild degree can evoke secondary high pump flow by returning of blood, but actually low cardiac output to systemic circulation (8). We double checked the presence of PFO using agitated saline with intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. Additionally, we performed patch closure of the aortic valve in concern of physiologic aortic regurgitation of mechanical aortic valve. Besides, RV function should be evaluated before LVAD, because significant RV dysfunction requires a biventricular assist device implantation rather than LVAD alone. RVFAC in a patient needing an LVAD implantation is usually 20%-30% (8). Our patient had mildly decreased TAPSE (14 mm), but RVFAC (60%) was within normal range.

In the postoperative period, the location of the septum in echocardiography provides us valuable information regarding optimal setting of LVAD. If rpm of LVAD is too high, septum will appear deviated to left side meaning a high risk of suction event obliterating inflow conduit by IVS. On the contrary, if rpm is too low, septum will appear deviated to right side, which means insufficient LV decompression (9). Furthermore, since euvolemic status is a prerequisite in manipulating rpm of LVAD, echocardiographic assessment of volume status using IVC is also important (Fig. 2F) (9). We controlled LVAD rpm and the patient's volume status maintaining a mid-position of septum under the guidance of echocardiography (Fig. 2C). The fatal complications such as thrombotic occlusion of the conduits can be detected with echocardiography. The amount of flow through the LVAD cannulas can be assumed with Doppler. The peak filling velocity of inflow and outflow cannula should be 0.7-2.0 m/sec and 0.5-2.0 m/sec, respectively (8). LVAD rpm resulting intermittent opening of aortic valve is another goal to balance between the risk of thrombosis and the benefit of maximal LV decompression in cases without closing aortic valve (8). However, we closed the aortic valve over concern of aortic regurgitation. Therefore, the occurrence of thrombosis at the sinuses of closed aortic valve and proximal ascending aorta needs to be monitored.

In conclusion, the first case of continuous-flow LVAD implantation as a destination therapy in Korea showed a favorable outcome. Development of an expanded role of LVAD as a destination therapy is expected in Korea. Additionally, appropriate assessment with echocardiography before and after LVAD implantation is indispensable for success of the procedure.

References

- 1.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Heitjan DF, Stevenson LW, Dembitsky W, Long JW, Ascheim DD, Tierney AR, Levitan RG, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1435–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long JW, Kfoury AG, Slaughter MS, Silver M, Milano C, Rogers J, Delgado R, Frazier OH. Long-term destination therapy with the HeartMate XVE left ventricular assist device: improved outcomes since the REMATCH Study. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2005.04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SJ, Milano CA, Tatooles AJ, Rogers JG, Adamson RM, Steidley DE, Ewald GA, Sundareswaran KS, Farrar DJ, Slaughter MS. Outcomes in advanced heart failure patients with left ventricular assist devices for destination therapy. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:241–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang JC. Rise of the machines: left ventricular assist devices as permanent therapy for advanced heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2282–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0910394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lietz K, Long JW, Kfoury AG, Slaughter MS, Silver MA, Milano CA, Rogers JG, Naka Y, Mancini D, Miller LW. Outcomes of left ventricular assist device implantation as destination therapy in the post-REMATCH era: implications for patient selection. Circulation. 2007;116:497–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowger J, Sundareswaran K, Rogers JG, Park SJ, Pagani FD, Bhat G, Jaski B, Farrar DJ, Slaughter MS. Predicting survival in patients receiving continuous flow left ventricular assist devices: the HeartMate II risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Park YH, Lim SH, Kwak YT, Kim H, Chang BC. Successful mechanical circulatory support as a bridge to transplantation. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2007;15:243–245. doi: 10.1177/021849230701500315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topilsky Y, Maltais S, Oh JK, Atchison FW, Perrault LP, Carrier M, Park SJ. Focused review on transthoracic echocardiographic assessment of patients with continuous axial left ventricular assist devices. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:187434. doi: 10.4061/2011/187434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mookadam F, Kendall CB, Wong RK, Kalya A, Warsame T, Arabia FA, Lusk J, Moustafa S, Steidley E, Quader N, et al. Left ventricular assist devices: physiologic assessment using echocardiography for management and optimization. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2012;38:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]