Abstract

A mediastinal mass was incidentally found on chest radiography in a 46-yr-old woman who had had myasthenia gravis (MG) for 2 months. Computed tomography revealed a 4-cm in size, well-defined, and lobulating mass with nodular calcification that was located in the thymus. Microscopically, the mass consisted of diffuse amorphous eosinophilic materials. These deposits exhibited apple-green birefringence under polarized light microscopy after Congo red staining. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that they were positive for both kappa and lambda light chains and negative for amyloid A. A diagnosis of localized primary thymic amyloidosis was finally made. After thymectomy, the symptoms of MG were controlled with reduced corticosteroid requirements. Localized thymic amyloidosis associated with MG has not been reported to date.

Keywords: Amyloidosis, Thymus, Mediastinum, Myasthenia Gravis

INTRODUCTION

Amyloidosis is a large group of diseases characterized by the deposition of misfolded extracellular fibrillar proteins in various organs and tissues. The accumulation of fibrillar materials subvert the tissue architecture and cause organ dysfunction.

Amyloidosis can be classified according to its biochemical nature as either primary or secondary (1). Primary amyloidosis consists of the deposition of fragments of Ig light chains (AL) that are produced by plasma cells. It can occur in association with clonal B-cell dyscrasia or otherwise benign conditions, as a systemic or localized form (2, 3). Secondary amyloidosis consists of the deposition of amyloid fibril proteins (AA) that are derived from circulating acute-phase reactants. That condition is caused by a number of chronic inflammatory diseases or neoplasms, which is typically a systemic disease (4-7). There are other protein subtypes that have been identified but they are far less common (8).

Amyloidosis also can be classified as a systemic disease (80%-90%) or as a localized disease (10%-20%) (9). Localized amlydoidosis may produce grossly detectable nodular masses, mostly in the upper respiratory tract (nasopharynx), lip, colon, skin, nails, and orbit (4, 10). Localized amyloidosis presenting as a mediastinal mass, especially in the thymus, is rare (11). To date, there have been only two reported cases of localized thymic amyloidosis. One case that presented with rheumatoid arthritis was reported in Japan (11). The other case was reported in Korea; the patient did not have a notable past medical history or subjective symptoms (2). A case of localized thymic amyloidosis that was manifested as a mediastinal mass in a patient with myasthenia gravis (MG) is reported here.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 46-yr-old woman was referred to Chungbuk national university hospital for thymectomy in February, 2013. Two months ago, she admitted for first developed ptosis, weakness in the neck, and dyspnea, and was diagnosed with acetylcholine receptor-positive MG. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a mass with calcification in the anterior mediastinum, which was suggestive of thymoma (Fig. 1). While undergoing cholinesterase inhibitor (Mestinon®) therapy, the patient developed a myasthenic crisis and was given immunoglobulin (Ig) therapy for 5 days under managed ventilator care. Treatment with corticosteroids then continued for a month. After the symptoms regressed, the patient was discharged. She visited the hospital again 2 months later for resection of the mediastinal mass. Given the clinical impression of thymoma-associated MG, mass resection and total thymectomy were performed.

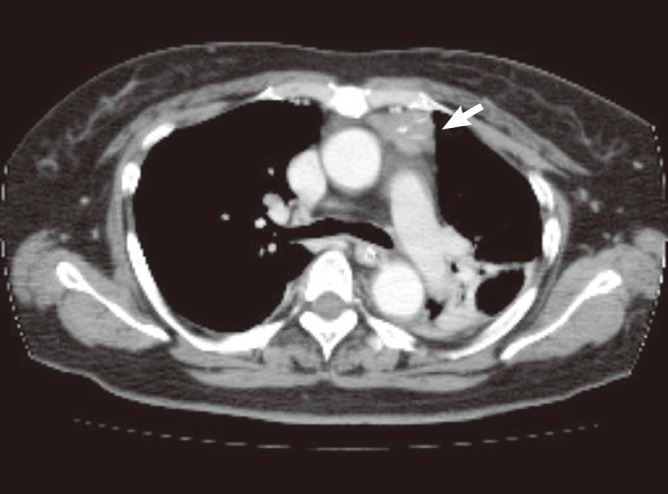

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography reveals an anterior mediastinal mass with calcifications (arrow).

Macroscopically, the resected mass, which measured 4×3×1.5 cm, was a relatively well-demarcated nodule that was surrounded by fat. The cut section was hard, yellow to gray, and calcified (Fig. 2). Microscopically, the mass was composed of amorphous eosinophilic hyaline materials surrounding islands of thymic tissues (Fig. 3). Stromal calcification and ossification were noted. The associated inflammatory reaction consisted of small lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells. These eosinophilic substances displayed apple-green birefringence under polarized light microscopy after Congo red staining (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that they were positive for kappa and lambda light chains and negative for serum amyloid A. These findings were consistent with primary (light chain) amyloidosis. Further examinations were done to rule out plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferatvie disorder. The serum IgG, IgA, and IgM levels were normal. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis did not detect any abnormal bands. Serum and urine immunoelectrophoresis did not indicate any definite abnormalities. The serum calcium levels were also within normal limits. To screen for systemic amyloidosis, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, echocardiogram, basic metabolic and biochemical panel, and liver function tests were performed. All returned values that were within normal limits. This suggested that the thymic amyloidosis was localized. Therefore, the final diagnosis of primary localized amyloidosis that only involved the thymus was made. The symptoms of MG were relieved dramatically after thymectomy.

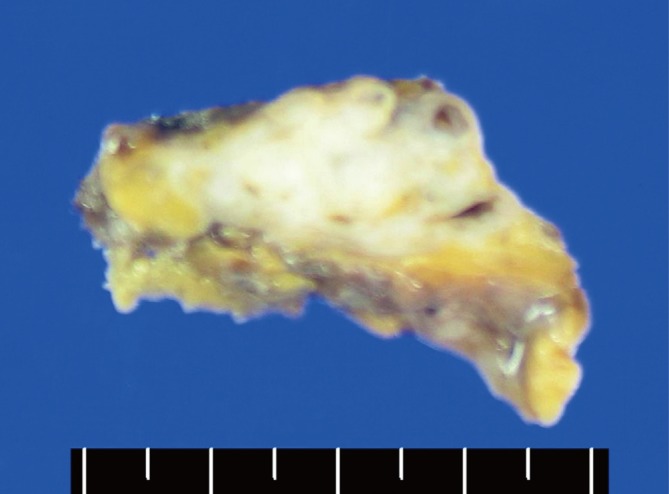

Fig. 2.

The resected mass is hard and has a lobulated contour. The cut surface is yellow to gray colored with calcification.

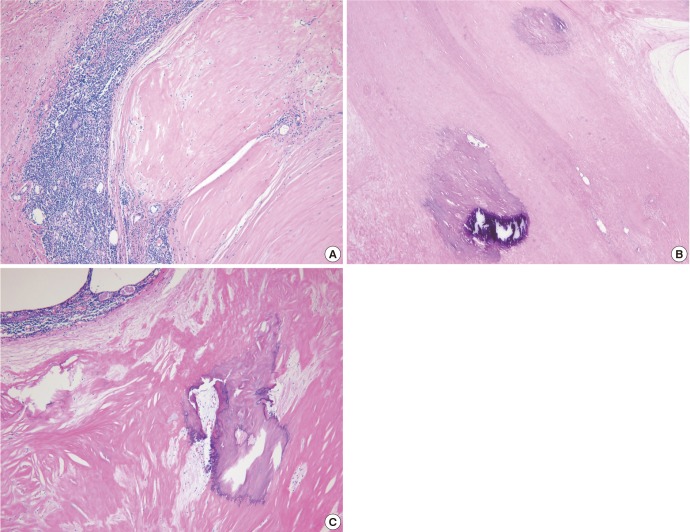

Fig. 3.

Histopathology of the mass, HE stained. (A) The mass consists of amorphous eosinophilic hyaline substances that surround islands of thymic tissues, ×40. (B, C) Calcification and ossification are present in the amyloid deposits, ×40.

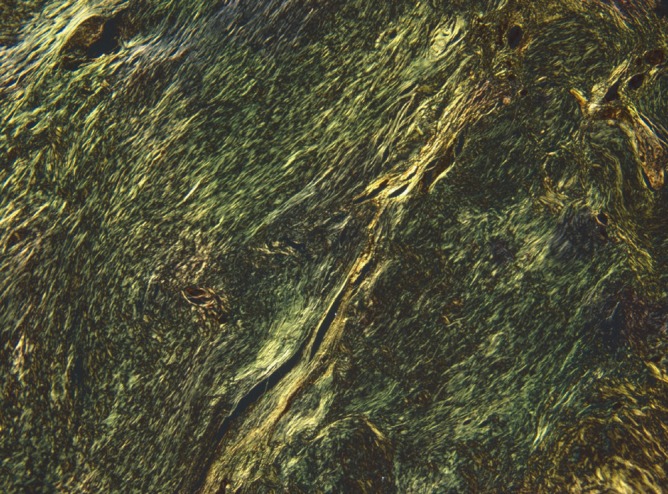

Fig. 4.

Apple-green birefringence is noted under polarized light microscopy after Congo red staining.

DISCUSSION

Amyloidosis is a rare clinical disorder that is defined as the progressive accumulation of amyloid deposits at a systemic or organ-specific level (8). Localized amyloidosis usually carries a better prognosis than the systemic form (12). Therefore, it is crucial to identify the local presence of amyloid. The diagnosis of localized amyloidosis is made primarily by exclusion (13). Shah et al. (13) suggested the criteria for the diagnosis of amyloidosis in the repiratory tract: positive immunohistochemical staining for kappa and lambda light chains in a respiratory tract biopsy, or negative staining for serum amyloid A protein, hereditary amyloid of transthyretin-type (TTR), and serum k and l chains; no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia on bone marrow aspirate, urine, or serum; characteristic distribution and pattern of localized respiratory tract disease on CT scan; negative radiolabelling of the serum amyloid P component (SAP scan); and negative echocardiogram. In the present case, following the same criteria with some modification, primary localized amyloidosis was diagnosed on the basis of the positive immunohistochemical staining for kappa and lambda light chains in the Congo red-positive area, negative staining for amyloid A protein, localized thymic involvement on CT scanning, lack of abnormal findings in serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis, and no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia.

Localized amyloidosis in the thymus is extremely rare: only two cases have been reported to date. One was the AA type (11) while the other was the AL type (2). The first case was reported by Takamori et al. (11) in 2004. They described a thymic mass that was composed of amorphous hyaline materials and was accompanied by a 5 yr history of rheumatoid arthritis. The final diagnosis was secondary amyloidosis localized in the thymus only (11). The other case was reported recently in Korea by Ha et al. (2). The diagnosis of primary AL amlyoidosis was confirmed by immunohistochemical detection of Ig light chains and there was no notable past medical history or symptoms. Notably, both cases were characterized by the presence of an isolated nodular thymic mass with scattered calcification and ossification.

The present case is the third case of localized thymic amlyoidosis in the world and the second such case in Korea. This case is remarkable in that the amlyoidosis presented as a localized thymic mass associated with MG. To our knowledge, such a case has not been reported to date. The patient had presented with the symptoms of MG 2 months previously. These symptoms then deteriorated to a myasthenic crisis. During the course of her disease, the thymic lesion was identified by a chest CT scan and was removed by thymectomy. Thereafter, the myasthenic symptoms of the patient were under controlled with reduced requirements of corticisteroids.

Thymic abnormalities are common in patients with MG. Thymic hyperplasia and thymoma are found in 65% and 15% of affected patients, respectively. The precise link between thymic lesions and the autoimmunity in MG remains unclear (14). In MG, the pathogenic antibodies (Abs) to acetylcholine receptor (anti-AChR Abs) are high-affinity IgGs. The production of such IgGs requires the interaction between activated AChR-specific CD4+ T cells and B cells: this interaction triggers the somatic mutation that converts common low-affinity anti-AChR Abs into high-affinity Abs (15). The AChR-specific CD4+ T cells are needed for the development of MG and are found in the blood and thymus (16). Therefore, regardless of the type of thymic pathology, most affected individuals improve after thymectomy (17). In the present case, the amyloidosis may have been provoked by the deposition of anti-AChR Ab-derived misfolded light chains, and the reduction of AChR-specific CD4+ T cells in thymic lesion by thymectomy may have relieved the myasthenic symptoms. However, the continuous use of corticosteroids before and after thymectomy made it difficult to ascertain whether thymectomy provides additional benefits. Therefore, we could not confirm the direct link between MG symptoms and thymic amyloidosis. Further investigations need to find the detail immunologic connections between two of them.

In conclusion, we describe a very rare case of the localized thymic amyloidosis with MG symptoms. A few cases of localized thymic amyloidosis have been reported before, but the case accompanying with MG has not been reported so far

References

- 1.Nomenclature of amyloid and amyloidosis: WHO-IUIS Nomenclature Sub-Committee. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:105–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ha SY, Lee JJ, Park HJ, Han JH, Kim HK, Lee KS. Localized primary thymic amyloidosis presenting as a mediastinal mass: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2011;45(Suppl 1):S41–S44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan B, Ramirez-Alvarado M, Sikkink L, Golderman S, Dispenzieri A, Livneh A, Gallo G. Free light chains in plasma of patients with light chain amyloidosis and non-amyloid light chain deposition disease: high proportion and heterogeneity of disulfide-linked monoclonal free light chains as pathogenic features of amyloid disease. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat A, Selmi C, Naguwa SM, Cheema GS, Gershwin ME. Currents concepts on the immunopathology of amyloidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2010;38:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson PG, Thompson JC, Webb NR, de Beer FC, King VL, Tannock LR. Serum amyloid A, but not C-reactive protein, stimulates vascular proteoglycan synthesis in a pro-atherogenic manner. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1902–1910. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wetmore JB, Lovett DH, Hung AM, Cook-Wiens G, Mahnken JD, Sen S, Johansen KL. Associations of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A with mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13:593–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westermark GT, Westermark P. Serum amyloid A and protein AA: molecular mechanisms of a transmissible amyloidosis. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2685–2690. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban BA, Fishman EK, Goldman SM, Scott WW, Jr, Jones B, Humphrey RL, Hruban RH. CT evaluation of amyloidosis: spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 1993;13:1295–1308. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.13.6.8290725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepys MB. Amyloidosis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:223–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takamori S, Yano H, Hayashi A, Fukunaga M, Miwa K, Maeshiro K, Shirouzu K. Amyloid tumor in the anterior mediastinum: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:518–520. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddachari RC, Chankar DA, Pramesh CS, Naresh KN, de Sousa CE, Dcruz AK. Laryngeal amyloidosis. J Otolaryngol. 2005;34:60–63. doi: 10.2310/7070.2005.03131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah PL, Gillmore JD, Copley SJ, Collins JV, Wells AU, du Bois RM, Hawkins PN, Nicholson AG. The importance of complete screening for amyloid fibril type and systemic disease in patients with amyloidosis in the respiratory tract. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2002;19:134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony DC, Frosch MP, De Girolami U. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Schmitt W, editor. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, professional edition. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008. pp. 1275–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conti-Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ. Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2843–2854. doi: 10.1172/JCI29894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohlfeld R, Toyka KV, Heininger K, Grosse-Wilde H, Kalies I. Autoimmune human T lymphocytes specific for acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 1984;310:244–246. doi: 10.1038/310244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgutti M, Conti-Tronconi BM, Sghirlanzoni A, Clementi F. Cellular immune response to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis: II. thymectomy and corticosteroids. Neurology. 1979;29:734–738. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]