Abstract

Background

CO and FT orthologs, belonging to the BBX and PEBP family, respectively, have important and conserved roles in the photoperiod regulation of flowering time in plants. Soybean genome experienced at least three rounds of whole genome duplications (WGDs), which resulted in multiple copies of about 75% of genes. Subsequent subfunctionalization is the main fate for paralogous gene pairs during the evolutionary process.

Results

The phylogenic relationships revealed that CO orthologs were widespread in the plant kingdom while FT orthologs were present only in angiosperms. Twenty-eight CO homologous genes and twenty-four FT homologous genes were gained in the soybean genome. Based on the collinear relationship, the soybean ancestral CO ortholog experienced three WGD events, but only two paralogous gene pairs (GmCOL1/2 and GmCOL5/13) survived in the modern soybean. The paralogous gene pairs, GmCOL1/2 or GmCOL5/13, showed similar expression patterns in pair but different between pairs, indicating that they functionally diverged. GmFTL1 to 7 were derived from the same ancestor prior to the whole genome triplication (WGT) event, and after the Legume WGD event the ancestor diverged into two branches, GmFTL3/5/7 and GmFTL1/2/4/6. GmFTL7 were truncated in the N-terminus compared to other FT-lineage genes, but ubiquitously expressed. Expressions of GmFTL1 to 6 were higher in leaves at the flowering stage than that at the seedling stage. GmFTL3 was expressed at the highest level in all tissues except roots at the seedling stage, and its circadian pattern was different from the other five ones. The transcript of GmFTL6 was highly accumulated in seedling roots. The circadian rhythms of GmCOL5/13 and GmFT1/2/4/5/6 were synchronized in a day, demonstrating the complicate relationship of CO-FT regulons in soybean leaves. Over-expression of GmCOL2 did not rescue the flowering phenotype of the Arabidopsis co mutant. However, ectopic expression of GmCOL5 did rescue the co mutant phenotype. All GmFTL1 to 6 showed flower-promoting activities in Arabidopsis.

Conclusions

After three recent rounds of whole genome duplications in the soybean, the paralogous genes of CO-FT regulons showed subfunctionalization through expression divergence. Then, only GmCOL5/13 kept flowering-promoting activities, while GmFTL1 to 6 contributed to flowering control. Additionally, GmCOL5/13 and GmFT1/2/3/4/5/6 showed similar circadian expression profiles. Therefore, our results suggested that GmCOL5/13 and GmFT1/2/3/4/5/6 formed the complicate CO-FT regulons in the photoperiod regulation of flowering time in soybean.

Keywords: CONSTANS, FLOWERING LOCUS T, Paralog, Ortholog, Functional divergence, Soybean

Background

The photoperiod pathway, which includes a number of genes that form its core, as well as input and output genes, is very important for angiosperms to flower at a precise time in a year [1]. The circadian-regulated gene CONSTANS (CO) is a central regulator of this pathway, which coordinates light and clock inputs in leaves to trigger the expression of florigen gene FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) [2,3]. In Arabidopsis, a long-day (SD) plant, the transcript peak of CO mRNA occurs late in the day in LD, but after dusk in SD [4]. CO protein, in turn, is stabilized by light and rapidly degrades in darkness, and activates the expression of FT in LD conditions [5,6]. In rice, a short-day (SD) plant, Hd1, the CO ortholog, functions in the promotion of Hd3a (the FT ortholog) expression in SD conditions, but in the inhibition of Hd3a expression in LD conditions [7,8]. Hd1 mRNA begins to accumulate after dusk and decrease before dawn [8]. In Populus trichocarpa, CO-FT regulon also plays a pivotal role in flowering and controlling of a highly adaptive trait for forest trees [9]. The day-length flowering response in temperate cereals, such as wheat and barley, appears to involve the activation of an FT and FT-like 1 (FT1) [10]. TaHD1 (a CO-like gene in wheat) can complement the rice hd1 mutant [11], and LpCO3 (a CO-like gene in Lolium perenne) can rescue the co mutant phenotype [12]. Thus, the CO-FT regulon is conserved among angiosperms analyzed, even though it has different modes in different species.

CO homologs belong to B-box family (BBX) family and are conserved in plants including algae [13-16]. The BBX (Pfam: PF01161) represents a subgroup of zinc finger proteins, which contain one or two B-box domains mediating protein-protein interactions in animals, yeast, and plants [17,18]. Besides B-box domains in the N-termini, some members of BBX family have a C-terminal CCT domain, which includes a nuclear import signal [4] and a domain of interaction with the ubiquitin ligase COP1 [6]. CO homologs can be sub-grouped into three major sub-types: type I with two B-box domains, type II with one B-box domain, and type III with one B-box domain and one degraded B-box domain [2,15,16]. Some members of type I genes, such as CO in A. thaliana, Hd1 in rice, and PnCO in Pharbitis nil, control flowering in different plants [12,14,15,19-25]. The CO homolog is also found in algae. CrCO from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii can complement the Arabidopsis co mutant and promote flowering [16], indicating the function of CO orthologs is ancient and conserved.

Phosphatidyl ethanolamine-binding protein family (PEBP, Pfam: PF00643) has now been identified in many kingdoms and their basic structures as well as sequences are evolutionarily conserved [26]. In plants, PEBP genes are mainly classified into three clades: FT-like, TFL-like and MFT-like clades [27]. MFT-like is ancestral to the other two clades and shown to be involved in the development of reproductive tissues in moss or seed development and germination in seed plants [28-31]. Several members of the TFL-like clade, such as CEN from Antirrhinum[32] and TFL1 from Arabidopsis, have important roles in delaying flowering and maintaining indeterminacy of inflorescence meristem [33]. As a major component of florigen, FT-like genes mediate the onset of flowering through the photoperiod pathway, vernalization pathways, and other pathways in all angiosperms examined [34-36]. FT/TFL1-like genes, such as PaFTL1 and PaFTL2, code for proteins with a TFL1-like function in gymnosperms [30]. Taken together, the first duplication event resulting in two families of plant PEBP genes (MFT-like and FT/TFL1-like) seems to coincide with the evolution of seed plants, in which independent control of bud and seed dormancy is required [30]. The second duplication resulting in the production of the FT-like and TFL1-like clades probably coincides with the evolution of angiosperms [30]. In addition, the similarity of amino acid among the FT- and FTL-like clades is high, and key amino acids are responsible for this functional divergence [37-39].

Gene duplications have occurred during plant speciation, and the generation of several paralogous copies allows gene diversification. Paralogs may retain the function of the ancestral genes, and thus act redundantly and/or additively due to the increased protein dosage. But they may also develop non-, sub- or neo-functions [40]. In soybean, about 75% genes are present in multiple copies [41], and about 50% of paralogs are differentially expressed. Most of them have undergone sub-functionalization and only a small proportion of the duplicated genes have been neo-functionalized or non-functionalized [42,43].

In this study, the evolutionary relationship between the BBX or PEBP gene family and plant speciation was investigated at the genome level. And then CO and FT orthologs were screened in the soybean genome. Based on the phylogenetic and the collinear relationship, 4 of CO orthologs (GmCOL1, 2, 5, and 13) and 6 of FT orthologs (GmFTL1 to 6) were identified in the soybean. Finally, the detailed expression profiles of these genes in soybean and their flowering functions in Arabidopsis were analyzed. The results suggest that in soybean there were more than one CO and FT orthologs with the function of flowering control.

Results and discussion

CO-like genes are ancient, whereas FT-like genes are recent in plants

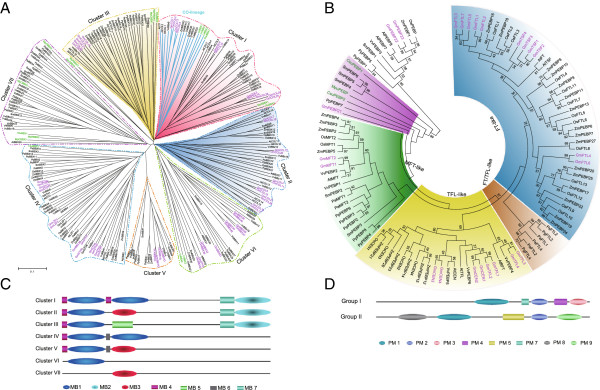

The profile-HMMs for the BBX family (PF00643) and the PEBP family (PF01161), including CO-like and FT-like genes, respectively, were employed through HMMER to search candidate genes of the two families in plants with available genomes, including two monocots (Oryza sativa and Zea mays), three eudicots (Vitis vinifera, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Glycine max), four gymnosperms (Picea sitchensis, Pinus radiate, Pinus pinaster, and Pinus sylvestris), one lycophyte (Selaginella moellendorffii), one moss (Physcomitrella patens), and six chlorophytes (Ostreococcus lucimarinus, Micromonas pusilla RCC299, M. pusilla CCMP1545, Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, Volvox carteri, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) (Additional file 1). Phylogenetic trees of the CO-like and FT-like gene families were similarly reconstructed by MEGA 5.0 with Neighbor-joining method (Figure 1A and B). MEME and MAST (http://meme.nbcr.net) were employed to investigate motifs and their organizations among different clusters of the BBX or PEBP family, respectively (Figure 1C and 2D).

Figure 1.

Phylogentic trees of plant BBX or PEBP family. The phylogenetic tree of plant BBX or PEBP genes reconstructed by MEGA 5.0 with the NJ method and the bootstrap test (1000). Soybean BBX or PEBP genes from soybean were in purple and from the algae in green. A, the phylogenetic tree of plant BBX gene family. The CO homologs were in different color background, and the blue branches were the candidate CO-lineage genes. B, the phylogenetic tree of plant PEBP gene family. Group I was in color background and Group II had no color. The motif organizations of the BBX or PEBP family based on the results of MEME and MAST, and different motifs were in different color, and the best match sequences was listed in Additional file 2. C, the motif organizations of different clusters of the BBX family. D, The motif organizations of different groups of the PEBP family.

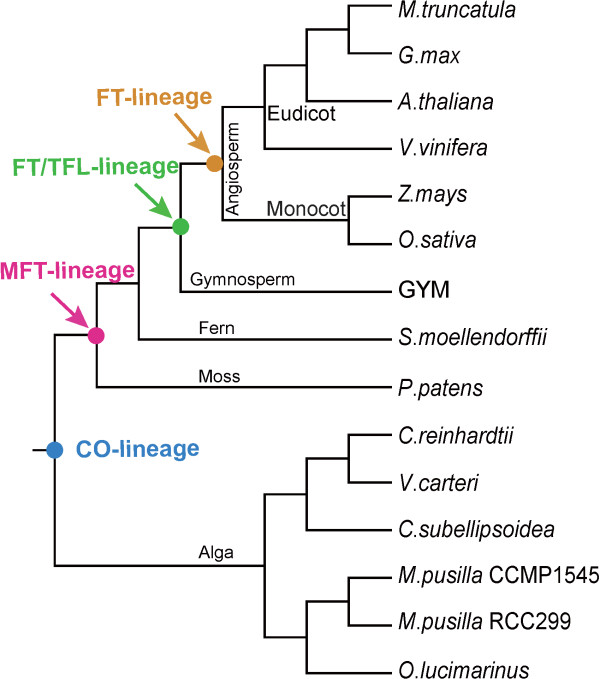

Figure 2.

The evolutionary processes of CO-lineage or FT-lineage. The blue, red, green and orange solid circle showed the earliest possible occurrence of CO-, MFT-, FT/TFL-, and FT-lineage during the evolutionary process of the plant, respectively. GYM was the gymnosperm, such as Picea sitchensis, Pinus radiate, P. pinaster and P. sylvestris.

Different BBX clusters had completely diverged before the divergence of bryophytes and pteridophytes [13]. According to the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1A) and their own motif organizations (Figure 1C, Additional file 2), the plant BBX family was grouped into seven clusters, Cluster I through VII. Among them, Cluster I, III, IV, VI, and VII can be found in the unicellular green algae and Cluster II and V first appeared in the moss plant. Thus, seven BBX clusters appeared prior to the occurrence of land plants. Based on the alignment results of SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), motifs MB1 and MB4 were equivalent to the B-box1 domain, and MB3 or MB6 to the B-box2 domain (a degraded B-box [15,16]), and MB2 and MB7 to the CCT domain. CO homologs contained conserved B-box1 domain and CCT-domain [4,15].The members of Cluster I, II and III also had both B-box1 and CCT-domain, suggesting that the members of the three clusters were the CO homologs. In addition, BBX Cluster I contained CO in Arabidopsis[14], Hd1 (OsBBX12) in rice [20], and CrCO (CrBBX1) in a green algae [16]. Thus, BBX Cluster I contained the CO orthologs from different species (Figure 1A), indicating that they formed the conserved motifs and functioned prior to the divergence of algae and plants and were monophyletic.

CO homologs probably represented as ancient regulators of photoperiod-dependent events [16]. Functionally, CrCO from C. reinhardtii shows important roles in processes regulated by the photoperiod and the circadian clock [16]. In the moss P. patens, PpCOL1 (PpBBX6 in this study) expression is controlled by the circadian clock [44]. Transcripts of PaCOL1 and PaCOL2 in Picea abies can also be regulated by the photoperiod [45]. For the flowering plants, CO and Hd1, display conserved functions in regulating the flowering time through affecting transcriptions of FT or Hd3a under the LD or SD conditions, respectively [14,20].

For the plant PEBP gene family, the members could be grouped into two groups, Group I and II, with conserved motif organization, respectively (Figure 1B and D, Additional file 2). MFT-likes, FT/TFL-likes, TFL-likes, and FT-likes belonged to Group I. Based on the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1B), MFT-like genes were presented in all the land plants, and may be the ancestral form of FT/TFL-like, TFL-like, and FT-like genes [28]. P. patens had only MFT-like genes, whose expressions were regulated by circadian rhythm with maximum expressions in gametangia and sporophytes, indicating an involvement in the development of reproductive tissues in the moss [28]. Similarly, the MFT-like genes display important roles in the seed development or dormancy in angiosperms, but do not affect the flowering time [29,31,46]. Before the appearance of seed plants, the function divergence of FT-like genes and TFL-like genes is not obvious, and the function of some PEBP genes is close to TFL-like genes, although their sequences and key motifs are much similar to that of FT-like genes [30,45]. Only in angiosperms, the function divergence of FT-like genes (as an activator) and TFL-like genes (as a repressor) is significant as oppositely regulating the flowering time in monocots and eudicots [38,47-54]. In addition, TSF not only plays a role as a floral promoter in the photoperiod pathway redundantly with FT, but also makes a distinct contribution to Arabidopsis flowering in SD conditions. TSF overexpression causes a precocious flowering phenotype independent of photoperiods and CO or FLC, indicating FT and TSF are differently regulated by distinct floral-inducing signals [55,56]. All above, FT-like genes are present as the main flowering regulator after the divergence of angiosperms and gymnosperms and show different functions from that of TSF-like genes.

Taken together, CO-lineage genes were present in different plants from the unicellular green alga to the flowering plant (Figure 2), and their functions were ancient and conserved. However, FT-lineage genes were functionally diverged from MFT-like or TFL-like genes (Figure 2) when flowering plants occurred. Thus, FT orthologs appeared later than CO orthologs, and the CO-FT regulon was a product of a very long evolutionary process. But the mechanism of CO regulating the FT transcription was conserved in the angiosperm, and they functioned together as a CO-FT regulon in regulation of the flowering time through a photoperiod-dependent mode [2,57].

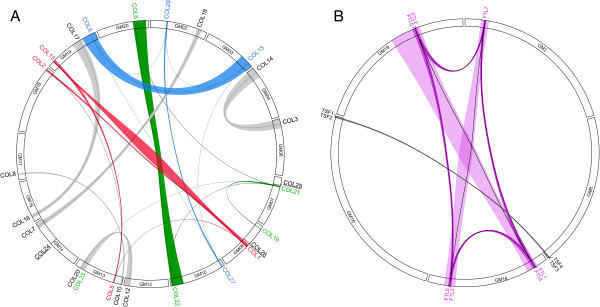

Duplications of the CO-FT regulon in the soybean evolution

In the soybean genome, 28 CO-like genes in total, named as GmCOL1 through 28, can be grouped into Cluster I, II and III (Figure 1A), and most of them except for COL24, 25, and 26 experienced WGD (Figure 3A). Three loci experienced the Gamma WGT and two WGD events, and then resulted in GmCOL1/2/5/13 (Cluster I), GmCOL6/19/21/22/23 (Cluster II), and GmCOL9/15/27/28 (Cluster III), respectively (Figure 3A). Others were divergent after the Glycine WGD event. Evolutionarily, the soybean CO orthologs may be anyone of Cluster I, II, and III. However, based on the phylogenetic tree, GmCOL1, 2, 5, and 13 among 28 CO-like genes were much closer to CrCO, CO, and Hd1 (Figure 1A), which showed flowering activity in plants [16,20]. Additionally, the syntenic blocks containing GmCOL1 or 2 and GmCOL5 or 13 in chromosomes were divergent after the legume WGD event according to the average Ks values of homologous blocks (0.3 ≤ Ks ≤ 1.5) (Table 1). Therefore, GmCOL1, 2, 5, and 13 were the good candidates of CO orthologs in the soybean, which was consistent with Jung et al. [58]. Therefore, they were selected for further study here.

Figure 3.

The collinear relationships of homologous blocks containing CO-like or FT-like genes. A, the collinear relationships among soybean CO-like genes GmCOL1/2/5/13, GmCOL6/19/21/22/23, and GmCOL9/15/27/28 were in red, green, and blue, respectively. The gray rainbows showed the collinear relationship arose only after the Glycine WGD event. Singleton genes were underlined. B, The collinear relationships among soybean FT- lineage genes. The rainbow in purple showed the collinear relationship among soybean FT-lineage genes, and that in green displayed the collinear relationships among soybean TSF-lineage genes.

Table 1.

Collinear relationships of homologous blocks containing CO or FT orthologs in soybean

| Gene 1 |

Block 1 |

Gene 2 |

Block 2 |

Averange Ks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr. | Start1 (bp) | Stop1 (bp) | Chr. | Start2 (bp) | Stop2 (bp) | |||

|

GmCOL1 |

GM08 |

20,564,643 |

23,533,251 |

GmCOL2 |

GM18 |

59,120,324 |

60,758,130 |

0.1804 |

|

GmCOL1 |

GM08 |

22,488,108 |

22,903,468 |

GmCOL5 |

GM13 |

7,094,033 |

7,353,077 |

0.7170 |

|

GmCOL1 |

GM08 |

22,268,496 |

22,705,283 |

GmCOL13 |

GM19 |

5,037,623 |

5,784,423 |

0.7074 |

|

GmCOL2 |

GM18 |

59,759,300 |

60,359,904 |

GmCOL5 |

GM13 |

6,762,198 |

7,353,077 |

0.6861 |

|

GmCOL2 |

GM18 |

59,768,883 |

60,286,871 |

GmCOL13 |

GM19 |

4,269,582 |

5,784,423 |

0.6852 |

|

GmCOL5 |

GM13 |

4,686,036 |

7,380,393 |

GmCOL13 |

GM19 |

1,047,196 |

6,070,543 |

0.2339 |

|

GmFTL7 |

GM02 |

3,884,100 |

7,368,892 |

GmFTL3, 5 |

GM16 |

26,025,808 |

32,876,516 |

0.2402 |

|

GmFTL7 |

GM02 |

5,819,578 |

6,251,781 |

GmFTL2, 6 |

GM19 |

35,107,064 |

36,353,817 |

1.020 |

|

GmFTL7 |

GM02 |

6,298,304 |

5,732,540 |

GmFTL1, 4 |

GM16 |

3,729,118 |

5,022,006 |

0.8591 |

|

GmFTL3, 5 |

GM16 |

30,464,871 |

31,024,893 |

GmFTL2, 6 |

GM19 |

35,107,064 |

36,353,817 |

0.9123 |

|

GmFTL3, 5 |

GM16 |

30,321,165 |

31,089,979 |

GmFTL1, 4 |

GM16 |

5,016,992 |

9,730,561 |

0.7530 |

| GmFTL2, 6 | GM19 | 27,993,447 | 37,257,559 | GmFTL1, 4 | GM16 | 6,662,519 | 3,315,381 | 0.2702 |

Note: The homologous blocks, containing CO or FT orthologs, were gained by MCScanX. Average Ks values of homologous blocks were the mean of Ks values of paralogous gene pairs in blocks.

There were 11 FT-like genes in the soybean (Figure 1B), and according to the collinear relationships (Figure 3B) they can be grouped into two clades, one including GmFTL1 to 7 and the other composing of GmTSF1 to 4. Compared with the previous results of Kong et al.[59], GmFTL1 to 6 were equivalent to GmFTL3a, 3b, 2a, 5a, 2b and 5b, and GmTSF1 to 4 corresponded to GmFTL1b, 1a, 6 and 4, respectively. GmFTL1-6 all experienced WGDs as well as tandom duplications (Figure 3B). GmFTL7 with only a shortened PEBP domain and lacking the N-terminal segment was diverged from its paralogous gene GmFTL3 (Table 1). However, GmFTL7 was strongly expressed in most tissues detected and induced by the photoperiod (Additional file 3). GmFTL3 (GmFTL2a) and GmFTL4 (GmFTL5a) coordinately control flowering and enable the adaptation of soybean to photoperiodic environments [59,60]. In Arabidopsis, FT mainly functions in LD while TSF makes a distinct contribution only in SD conditions [56,61,62], indicating the function of FT and TSF is divergent in regulating the flowering time. In soybean, GmTSF1 and -2 displayed much similar sequences with TSF. GmTSF3/4 showed much similar sequences with FT than that with TSF (Additional file 4), but they should be the TSF lineage according to the collinear relationship (Figure 3B). Furthermore, ectopic expression of GmTSF3 and GmTSF4 in Arabidopsis did not have flower-promoting activities under LD conditions (Additional file 5), so did TSF in Arabidopsis. Thus, GmFTL1 to 6 were here selected as soybean FT orthologs for further study.

Expression divergences among the soybean CO and FT paralogs showing spatio-temporal functions of CO-FT regulons

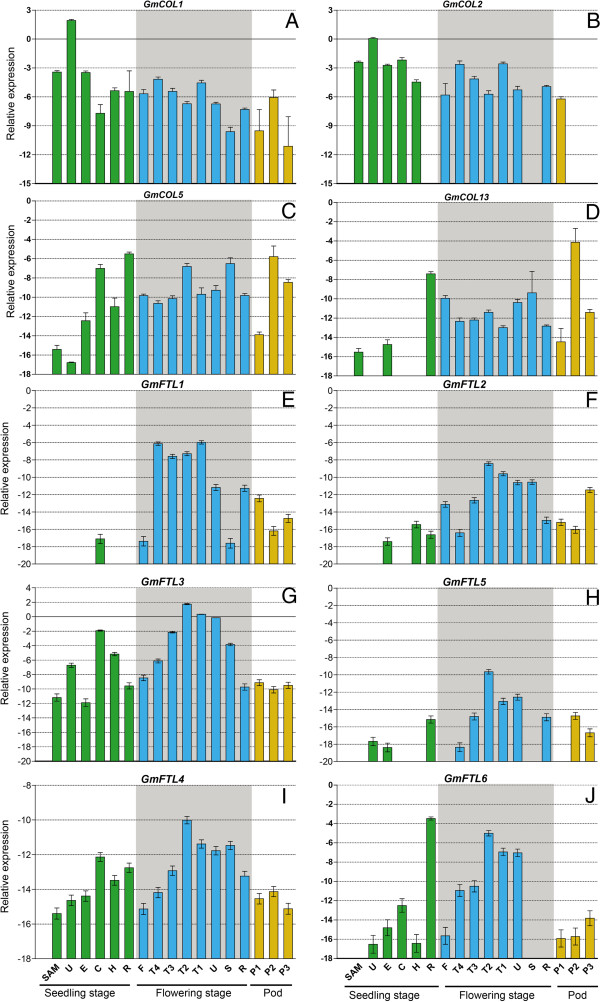

In soybean, spatio-temporal expression profiles of four candidate CO orthologs (Figure 4A-D) and six FT orthologs (Figure 4E-J) were investigated by quantitative real time RT-PCR at the stages of seedling and flowering under SD conditions (8 h light/16 h dark).

Figure 4.

Expression profiles of soybean CO or FT orthologs. A, B, C and D was expression profile of GmCOL1, 2, 5 and 13, respectively. E, F, G, H, I and J was expression profile of GmFTL1, 2, 3, 5, 4 and 6, respectively. R, root; H, hypocotyl; C, cotyledon; E, epicotyl; U, unifoliolate leaf; S, stem; T1, T2, T3, T4, the first, second, third and fourth trifoliolate leaf, respectively; F, flower; SAM, the shoot apex (including the apical meristem and immature leaves) at the seedling stage. P1, P2, and P3: seven, fourteen and twenty one days after the onset of flowering, respectively. The geometric means of GmACT11 and GmUKNI transcripts were used as the reference transcript.

The transcript of GmCOL1/2 accumulated much more than that of GmCOL5/13 in most tissues tested, and the expressions of GmCOL1 and GmCOL5 did not show tissue-specific, while GmCOL2 and GmCOL13 displayed distinct spatio-temporal expression patterns. For example, the expression of GmCOL2 was not detected in roots at the seedling stage, in the stems at flowering, and in pods at 14 and 21 DAF (Days After Flowering) (Figure 4B). And transcripts of GmCOL13 were undetectable in unifoliolates, cotyledons, and hypocotyls (Figure 4D). GmCOL1, 2, and 5 were expressed in cotyledons and unifoliolates at the seedling and flowering stages (Figure 4A, B and C). For the photoperiod-sensitive plant, the photoperiodic signals at the seedling stage are important to regulate flowering time. These results indicated that GmCOL13 may not be the key gene of photoperiodic responses during the early stage of floral induction in soybean.

The expressions of GmFTL1 and GmFTL2 were undetectable in unifoliolates, but they strongly expressed in trifoliolates at the flowering time, and transcripts of other four GmFTLs were lower in leaves at the seedling stage than that at the flowering time (Figure 4E-J). So, soybean GmFTL genes were induced along with developmental progress. Amongst the six soybean FTL genes, GmFTL3 showed higher expression level compared to that of the other genes in most of the tissues examined (Figure 4G), suggesting that GmFTL3 was very important to promote flowering in soybean, as indicated by Kong et al. [59]. GmFTL4 also was constitutively expressed but at relatively lower level compared with GmFTL3. In the seedling stage, GmFTL3 and 4 were expressed at higher levels than their paralogs, GmFTL5 and GmFTL6, respectively. GmFTL1, 3, and 4 were strongly expressed in cotyledons (Figure 4E, G and I), which can produce sufficient FT proteins to induce flowering in Arabidopsis[63], suggesting that these three genes were important for floral induction at the early stages of soybean development. GmFTL5 was expressed at low levels and was not detected in shoot apical meristems (SAM), cotyledons, and hypocotyls at the seedling stage as well as stems at the flowering stage (Figure 4H). The expression of GmFTL6 was the highest one among six soybean FTL genes in roots at the seedling stage, but no expressions were detected in roots at the flowering stage (Figure 4J). Noticeably, expressions of GmFTL1, 2, 3, 4, 6 were detected in flowers, and GmFTL1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 were expressed in pods (Figure 4), suggesting that FTL genes kept the ancient function of the PEBP family and may be important in reproductive development.

CO regulates FT mainly in leaves, the receptors of photoperiod signals. Soybean unifoliolates only were competent for receiving the signal of SD to promote flower initiation and 3 days of short-day treatment were sufficient for floral induction [64]. As Figure 4 shown, the transcripts of GmCOL1/2/5 and GmFTL3/4/5/6 were detected in unifoliolate leaves at the seedling stage. In addition, cotyledons were shown to be another receptor of photoperiod signals besides leaves [63]. Expectedly, GmCOL1/2/5 and GmFTL1/2/3/4/6 were expressed in the cotyledons at the seedling stage (Figure 4). Combined results indicated that GmCOL1/2/5 and GmFTL3/4/6 had important roles in response to photoperiod at the soybean seedling stage.

The circadian rhythm of soybean CO-FT regulons in leaves

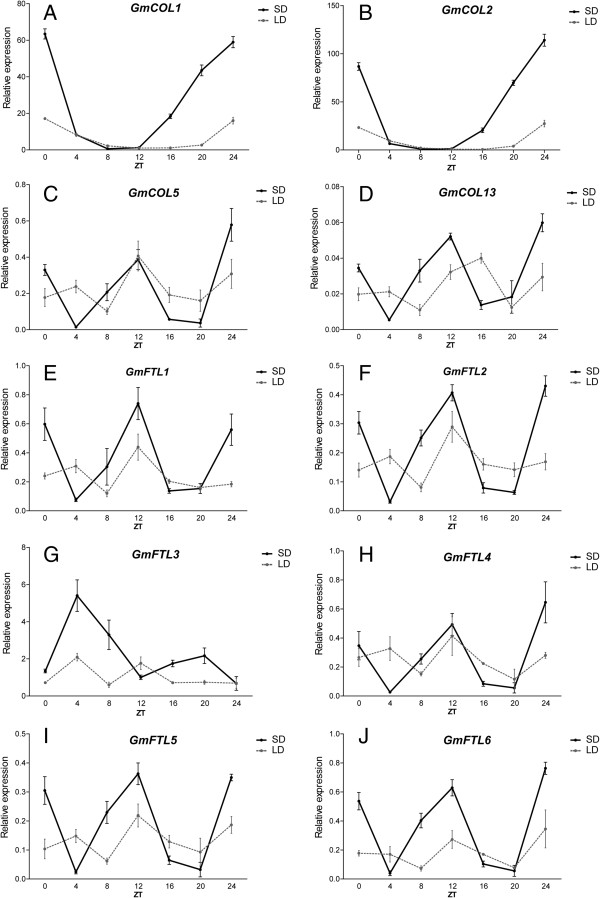

To investigate the circadian rhythm of the candidate CO-FT regulon genes, transcriptions of 10 genes were detected in the leaves at the stage of the first trifoliolate fully opening under SD (8 h light/16 h dark) or LD (16 h light/8 h dark) conditions (Figure 5). Transcriptional circadian patterns of the paralog gene pair, GmCOL1 and 2, were very similar under both SD and LD conditions, and expression levels was much higher in SD conditions than LD conditions. Their expression peaks were present at dawn, and after that their expressions decreased until dusk (Figure 5A and B), which indicated that the two genes were strongly induced by darkness and inhibited by light. The expression rhythms of GmCOL1 and 2 were similar to that of Hd1 in rice, in which the abundance of Hd1 mRNA was restricted to the dark period under SD conditions [65]. In addition, expression patterns of LjCOa, one of four CO homologs in Lotus japonicus, were also similar to that of GmCOL1 and 2 under SD or LD conditions [66]. Compared to GmCOL1 and 2, GmCOL5 and 13 were expressed at much lower level with different expression profiles in leaves (Figure 5C and D). In addition, the expression levels of GmCOL5 were ten folds higher than those of GmCOL13, although they showed similar expression patterns under SD or LD conditions. Under SD conditions, expression peaks of GmCOL5 and 13 occurred at dawn and ZT12, respectively. Under LD conditions, one expression peak of GmCOL5 and 13 occurred at ZT4, and the other at ZT12 and ZT16, respectively (Figure 5C and D).

Figure 5.

The circadian rhythm expression of soybean CO and FT orthologs under SD or LD conditions. A to D, the expression patterns of GmCOL1, 2, 5, 13, respectively. E to J, the expression patterns of GmFTL1-6, respectively. Seedlings were grown in SDs (8 h light/16 h dark cycles) or LDs (16 h light/8 h dark cycles) until the first trifoliolate leaf was fully expanded. Five trifoliolate leaves as one sample were collected at the times shown after dawn (ZT 0). Relative expressions were normalized to GmUKNI transcripts. Average and SD values for three replications are given for each data point.

According to the circadian rhythm of six soybean FT-like genes (Figure 5E-J), five genes have similar expression patterns under SD conditions except GmFTL3. The expression of GmFT1/2/4/5/6 occurred at dawn and peaked at ZT12 under SD conditions. But the expression peak of GmFTL3 was at ZT4 (Figure 5G), which was consistent with previous reports in soybean [59,60] and in rice [8]. Under LD conditions, all six GmFTL-like genes showed similar expression rhythms (Figure 5E-J). For example, the expressions of six soybean FT-like genes reached to the maximum level at ZT4 and ZT12.

According to the diurnal rhythms of four soybean CO and six FT genes, GmCOL5 and 13 showed similar expression patterns with GmFTL1, 2, 4, 5, and 6, indicating that the paralogous gene pair GmCOL5 and 13 have important roles in regulation of expressions of GmFTL1, 2, 4, 5, and 6, and they may be composed of the soybean complicate and multiple CO-FT regulons to sense the circadian and photoperiodic signals.

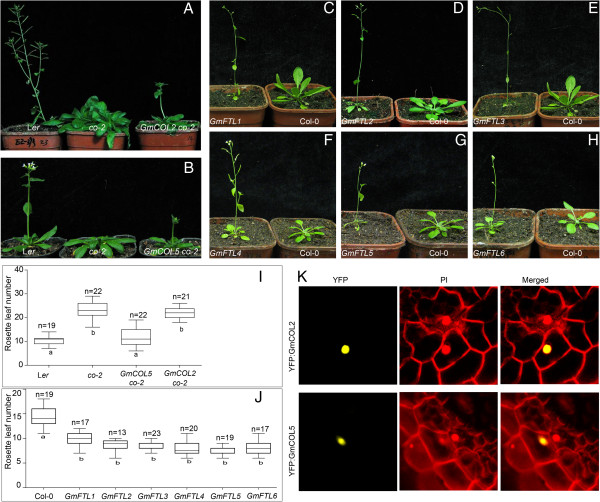

Ectopic activity on Arabidopsis flowering of GmCOLs and GmFTLs

In Arabidopsis, the CO paralog genes, COL1 and COL2, have little effect on flowering time [67], and other members of BBX Cluster I genes, COL3 and COL5, do not regulate the flowering time in Arabidopsis[68,69]. However, COL9, belonging to the BBX cluster II, is involved in regulation of flowering time by repressing the expression of CO, concomitantly reducing expressions of FT and delaying floral transition [70]. That indicates the functions of CO-like genes are not redundant in controlling the flowering time, and it may resulte from the rapid evolution of CO-like genes in plants [13]. To investigate the flowering functions of soybean CO orthologs, GmCOL2 and GmCOL5 under control of CaMV 35S promoter were introduced into the co mutant (co-2), respectively. For GmCOL2, no significant changes in flowering time were detected in the over-expressing lines in LD conditions (Figure 6A and I). By contrast, over-expression of GmCOL5 was able to rescue the late-flowering phenotype of co mutant (Figure 6B and I), indicating that GmCOL5 gene may be a functional CO ortholog in soybean.

Figure 6.

Flowering function analysis in Arabidopsis and the subcellular localizations of two soybean CO-lineage genes. A and B showed the phenotypes of overexpression of GmCOL2 and 5 in co-2 mutants, respectively. C to H, phenotypes of over-expression of GmFTL1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, respectively. I, total rosette leaf numbers of transgenic lines of GmCOL2 or 5 in co-2 mutants. J, total rosette leaf numbers of transgenic lines of GmFTL1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 at flowering time. n, the total number of tested transgenic lines. Box plot showed total rosette leaf numbers of each line at the beginning of flowering and was generated using GraphPad Prism 5 software. The top of the box is the 75th percentile. The bottom of the box is the 25th percentile. The horizontal line intersecting the box is the median value of the group. Horizontal lines above and below the box represent maximum and minimum values, respectively. Boxes with dissimilar letters are significantly different at P < 0.01 after one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). K, The subcellular localizations of GmCOL2 and 5 tagged by YFP at the N-terminal in the soybean leaves. PI (Propidium iodide) strain was selected to mark the cell walls.

FT and its orthologs are the universal and conserved promoters of flowering in different plants [34,48,59,65,71]. Over-expressions of GmFTL3 (GmFTL2a) or 4 (GmFTL5a) can promote the flowering in Arabidopsis[59,60]. To identify the flowering activity of soybean FT-like paralogs, all constructs of GmFTL1 to 6 genes under control of CaMV 35S promoter were respectively introduced into Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia (Col-0) (Figure 6C-H and I). Besides GmFTL3 or 4, other four soybean FTL genes can also change the flowering time of Arabidopsis (Figure 6C-H and I), suggesting that these paralogs of FTL genes may be functional FT orthologs in soybean. However, individual GmFTL genes had their own specific functions, because their spatio-temporal expression patterns were quite different.

In Arabidopsis, TSF and FT are differently regulated by distinct floral-inducing signals, so they show different functions on flowering in different conditions [56,61]. Functions of GmTSF3, GmTSF4 and GmPEBP21 in promoting flowering were further evaluated through heterologous over-expressions in Arabidopsis under LD conditions. The results showed that no significant changes in flowering time were detected in over-expression lines of GmTSF3 and GmTSF4, compared to Arabidopsis wild type (Additional file 5), suggesting that they may not be the FT-lineage genes. Although GmPEBP21 was much similar to FT in sequence (Additional file 4), it was not clustered into the FT-like (Figure 1B). And overexpression of GmPEBP21 showed no effect on the flowering of Arabidopsis (Additional file 5), indicating that it also was not a functional FT gene.

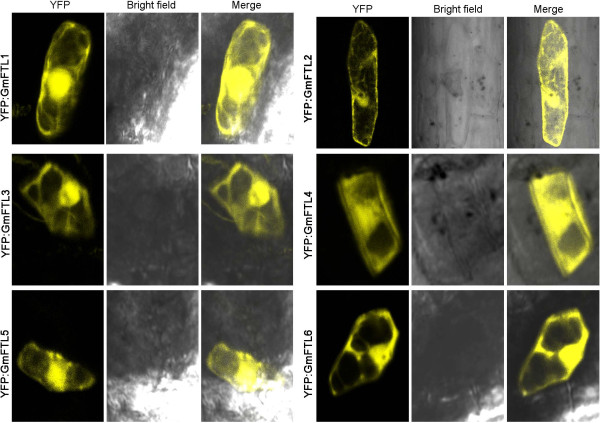

Conserved subcellular localization of soybean CO and FT-lineage proteins

Constructs of GmCOL2, GmCOL5, and GmFTL1 to 6 genes tagged by a reporter gene (YFP) at the N- or C-terminal were employed to investigate the subsucellular localization through the particle bombardment in the young soybean leaves. Fluorescence signals of YFP-GmCOL2 and YFP-GmCOL5 were only present in the nucleus (Figure 6K), which were similar to CO homologous proteins in other species [14,20]. All six GmFTL proteins also resembled to FT homologous proteins in other plants [72,73] and localized in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Subcellular localizations of six soybean FT orthologs tagged by YFP at the N-terminal in the soybean leaves.

Conclusion

BBX gene family contained seven clusters and the CO-homolog cluster were diverged from other clusters at the occurrence of plants. PEBP gene family had three groups and FT-lineage genes were diverged from MFT- and TFL-lineage genes at the occurrence of angiosperms. The role of the CO-FT regulon in photoperiodic regulation of flowering time was conserved, although the evolutionary rates of CO- and FT-lineage genes were different in angiosperms. In soybean, an ancient CO-lineage gene experienced three polyploidy events, and then formed four candidate of CO genes, GmCOL1, 2, 5, and 13. Six FT-lineage genes, GmFTL1-6, were from an ancient locus prior to the WGT event. Based on the spatio-temporal expression profiles, GmCOL1/2/5 and GmFTL3/4/6 were shown to play important roles in responses to photoperiod at the seedling stage. GmCOL5, GmFTL1 to 6 showed flowering activity in Arabidopsis, suggesting that at least these genes may be the candidates of functional CO-FT regulons in soybean. Therefore, the CO-FT regulon in soybean was complicate and had multiple ones instead of a single one as in Arabidopsis, which may function synergistically in a spatio-temporal mode to control photoperiodic flowering.

Methods

Plant Materials

The soybean cultivar (Kennong18) was grown in the greenhouse under SD conditions (8 h light/16 h dark) at 24-28°C. The roots, hypocotyls, epicotyls, cotyledons, unifoliolate leaves and shoot apex (including the apical meristem and immature leaves) were sampled when the unifoliolate leaves were fully expanded (about two weeks after sowing). Other sample of the root, stem, unifoliolate leaves, various trifoliolate leaves, petiole and flower were harvested when the fourth trifoliolate were fully expanded (~45 days after sowing, flowering onset). Pods were sampled at 7, 14 and 21 days after flowering. For circadian samples, plants were grown in SD (8 h light/16 h dark) or LD (16 h light/8 h dark) conditions. When the first trifoliolate leaves were fully expanded, leaves were collected at 4 h intervals. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use.

Data sets and identification of the PEBP or BBX family

Protein sequences from the completely sequenced genomes were downloaded from Phytozome V8.0 (http://www.phytozome.net), including two monocots (Oryza sativa and Zea mays), three eudicots (Vitis vinifera, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Glycine max), one lycophyte (Selaginella moellendorffii), one moss (Physcomitrella patens), and six chlorophytes (Ostreococcus lucimarinus, Micromonas pusilla RCC299, M. pusilla CCMP1545, Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, Volvox carteri, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii). Additionally, sequences of four gymnosperms (Picea sitchensis, Pinus radiate, Pinus pinaster, and Pinus sylvestris) were gained from Protein Knowledgebase (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/).

In order to provide a uniform nomenclature for the B-box protein family, all the genes with B-box domain were classified as the BBX family [18]. HMMER 3.0 [74] was employed to identify the members of the BBX family (Pfam: PF00643) and the PEBP family (Pfam: PF01161) through their own profile-HMMs in 13 genomes.

Phylogenetic analysis

Clustalw 2.0 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) was used to aligned protein sequences of the BBX or PEBP family with default parameters. The reconstructions of phylogenetic trees were conducted through MEGA 5.0 [75]. Neighbour-joining (NJ) was used to construct different trees. To estimate evolutionary distances, the proportion of amino acids differences were computed using Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) or Poisson correction models. To handle gaps and missing data, the pairwise-deletion option was selected. Bootstraps with 1000 replicates for Poisson correction model were performed to assess node support.

Collinearity analysis of the soybean BBX or PEBP gene family

The modern soybean genome has experienced two “recent” whole-genome duplications (WGDs), and a more ancient triplication (Gamma WGT), and about 75% of the genes are present in multiple copies [41,76]. In soybean, the putative homologous chromosomal regions were identified by MCScanX [77] according to the alignment of protein sequences. For a protein sequence, the best five non-self hits in the soybean genome that met an E-value threshold of 10-10 were reported. And the homologous blocks including at least 5 collinear gene pairs and the gap number of gene pairs was not more than 20. The schematic diagrams for the collinearity of the members of BBX or PEBP family were drawn by Circos [78] (http://circos.ca/).

Gene cloning and constructing expression vectors

The full CDS sequences of soybean CO orthologs (GmCOL1, 2, 5, and 13), FT orthologs (GmFTL1-6), GmTSF1-4, and GmPEBP21 were cloned into the entry vector (pGWCm) [79] and then recombined into appropriate destination vectors, pLEELA vector for overexpression in Arabidopsis or 2X35S∷Gateway cassette : YFP for the subcellular localization in soybean young leaves, with the Gateway technology (Invitrogen).

Quantitative gene expression analysis

The procedure used for RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and PCR was as described by Hu, et al[80]. According to the specificity and efficiency of the primer pairs, the soybean CO or FT orthologs were designed by Beacon Designer 7.9, and at least one primer was specific for the target gene primer pairs (Additional file 6). Both GmACT11 and GmUKN1 were served as reference genes for the tissue-expression trials, and GmACT11 was selected as the reference gene for the photoperiodic experiments.

Transformation in Arabidopsis and growth conditions

Transformation of WT Col-0 and co mutant plants with Agrobacterium bacteria carrying recombinant constructs was performed using the floral dip method [81,82]. For each construct, at least three independent T1 lines were selected analyzed for flowering time under the LD condition (22-24°C, 150 μmol · m-2 sec-1).

Subcellular localization

Transient expression of GmCOL2, GmCOL5 and GmFTL1 to 6 tagged by YFP in soybean young leaves was performed with a Model PDS-1000/He Biolistic Particle Delivery System (Bio-Rad). 10 micrograms of purified plasmids were coated with 500 μg 1 μm-gold particles, as described by the manufacturer. After bombardment, young soybean leaves were incubated overnight at 25°C on solid 1/2 MS medium. Fluorescent cells were imaged by confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, Leica Microsystem, Wetzlar, Germany). YFP was excited by the 514-nm argon laser line, and PI (Propidium iodide) stain was excited using a 561-nm He-Ne laser. Fluorescence was detected using photomultiplier tube settings as follows: YFP (520 to 560 nm), and PI (570 to 620 nm). At last, post-acquisition image analyzing and processing were performed using MBF ImageJ (version 1.46) (https://www.macbiophotonics.ca/).

Authors’ contributions

CF carried out all the analysis and interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. RH, XZ, CF carried out experiments of GmFTLs. XW gave some good advices on writing the manuscript. WZ, QZ, JM and CF done some works of GmCOLs. YF conceived the project, supervised the analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The information of the BBX or PEBP family. Sheet Gm, At, Vv, Os, Zm, Pp, and Sm showed the information of G. max, A. thaliana, V. vinifera, O. sativa, Z. mays, P. patens and S. moellendorffii, respectively; Sheet Gymnosperm included P. sitchensis, P. radiate, P. pinaster, and P. sylvestris; Sheet Algae included O. lucimarinus, M. pusilla RCC299, M. pusilla CCMP1545, C. subellipsoidea, V. carteri, and C.reinhardtii.

The best match sequences of motifs for the BBX or PEBP family.

Spatio-temporal expressions of GmFTL7. R, root; H, hypocotyl; C, cotyledon; E, epicotyl; U, unifoliolate leaf; S, stem; T1, T2, T3, T4, the first, second, third, and fourth trifoliolate leaf, respectively; F, flower; SAM, the shoot apex (including the apical meristem and immature leaves) at the seedling stage. P1, P2, and P3: seven, fourteen and twenty one days after the onset of flowering, respectively. The geometric means of GmACT11 and GmUKNI transcripts were used as the reference transcript. The bars are means of three replicates, and each replicate represented a pool from at least five plants, and means was formulated as ⊿Ct = Ct(Target gene)-Ct(geometric means of reference genes).

The similarity between soybean and Arabidopsis FT-like genes.

Phenotype of GmTSF3 , GmTSF4 and GmPEBP21 over-expressing in Arabidopsis. A, The phenotype of transgenic lines. B, The rosette leaf number of the transgenic lines at flowering. n showed the total detected lines. Box plot showed total rosette leaf numbers of each line at the beginning of flowering and was generated using GraphPad Prism 5 software. The top of the box is the 75th percentile. The bottom of the box is the 25th percentile. The horizontal line intersecting the box is the median value of the group. Horizontal lines above and below the box represent maximum and minimum values, respectively.

The primers of soybean CO or FT -lineage genes.

Contributor Information

Chengming Fan, Email: fanchengming@gmail.com.

Ruibo Hu, Email: hurb@qibebt.ac.cn.

Xiaomei Zhang, Email: zxmzh@163.com.

Xu Wang, Email: wangxuen@gmail.com.

Wenjing Zhang, Email: xiaocuishan@163.com.

Qingzhe Zhang, Email: zhangqz1020@163.com.

Jinhua Ma, Email: majinhua3347@163.com.

Yong-Fu Fu, Email: fufu19cn@163.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by 863 program (2013AA102602), Transgenic program (2011ZX08009-001 and 2011ZX08004-005), 973 Program (2010CB125906), and the National Natural Science Funds (31000681).

References

- Reeves PH, Coupland G. Response of plant development to environment: control of flowering by daylength and temperature. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F. CONSTANS and the evolutionary origin of photoperiodic timing of flowering. J Exper Botany. 2011;62(8):2453–2463. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turck F, Fornara F, Coupland G. Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:573–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez P, Wheatley K, Robson F, Onouchi H, Valverde F, Coupland G. CONSTANS mediates between the circadian clock and the control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2001;410(6832):1116–1120. doi: 10.1038/35074138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F, Mouradov A, Soppe W, Ravenscroft D, Samach A, Coupland G. Photoreceptor regulation of CONSTANS protein in photoperiodic flowering. Science. 2004;303(5660):1003–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1091761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S, Marchal V, Panigrahi KC, Wenkel S, Soppe W, Deng XW, Valverde F, Coupland G. Arabidopsis COP1 shapes the temporal pattern of CO accumulation conferring a photoperiodic flowering response. The EMBO journal. 2008;27(8):1277–1288. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T, Oikawa T, Sugiyama N, Tanisaka T, Yano M, Shimamoto K. Phytochrome mediates the external light signal to repress FT orthologs in photoperiodic flowering of rice. Genes & Dev. 2002;16(15):2006–2020. doi: 10.1101/gad.999202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayama R, Yokoi S, Tamaki S, Yano M, Shimamoto K. Adaptation of photoperiodic control pathways produces short-day flowering in rice. Nature. 2003;422(6933):719–722. doi: 10.1038/nature01549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlenius H, Huang T, Charbonnel-Campaa L, Brunner AM, Jansson S, Strauss SH, Nilsson O. CO/FT regulatory module controls timing of flowering and seasonal growth cessation in trees. Science. 2006;312(5776):1040–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1126038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenup A, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES, Trevaskis B. The molecular biology of seasonal flowering-responses in Arabidopsis and the cereals. Ann Bot (Lond) 2009;103(8):1165–1172. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto Y, Kisaka M, Fuse T, Yano M, Ogihara Y. Characterization and functional analysis of three wheat genes with homology to the CONSTANS flowering time gene in transgenic rice. Plant J. 2003;36(1):82–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Storgaard M, Andersen CH, Nielsen KK. Photoperiodic regulation of flowering in perennial ryegrass involving a CONSTANS -like homolog. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;56(2):159–169. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-2647-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagercrantz U, Axelsson T. Rapid evolution of the family of CONSTANS LIKE genes in plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(10):1499–1507. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putterill J, Robson F, Lee K, Simon R, Coupland G. The CONSTANS gene of Arabidopsis promotes flowering and encodes a protein showing similarities to zinc finger transcription factors. Cell. 1995;80(6):847–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S, Dunford RP, Coupland G, Laurie DA. The evolution of CONSTANS-like gene families in barley, rice, and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;131(4):1855–1867. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano G, Herrera-Palau R, Romero JM, Serrano A, Coupland G, Valverde F. Chlamydomonas CONSTANS and the evolution of plant photoperiodic signaling. Curr Biol. 2009;19(5):359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug A, Schwabe JW. Protein motifs 5. Zinc fingers. FASEB J. 1995;9(8):597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Kronmiller B, Maszle DR, Coupland G, Holm M, Mizuno T, Wu SH. The Arabidopsis B-box zinc finger family. Plant Cell. 2009;21(11):3416–3420. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert LS, Robson F, Sharpe A, Lydiate D, Coupland G. Conserved structure and function of the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS in Brassica napus. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37(5):763–772. doi: 10.1023/A:1006064514311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Katayose Y, Ashikari M, Yamanouchi U, Monna L, Fuse T, Baba T, Yamamoto K, Umehara Y, Nagamura Y. et al. Hd1, a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice, is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell. 2000;12(12):2473–2484. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yu J, McIntosh L, Kende H, Zeevaart JA. Isolation of a CONSTANS ortholog from Pharbitis nil and its role in flowering. Plant Physiol. 2001;125(4):1821–1830. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JL, Yang Q, Liang F, Xing YJ, Wang Z. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a novel CONSTANS-like gene from potato. Biochem Biokhimiia. 2007;72(11):1241–1246. doi: 10.1134/S0006297907110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almada R, Cabrera N, Casaretto JA, Ruiz-Lara S, Gonzalez Villanueva E. VvCO and VvCOL1, two CONSTANS homologous genes, are regulated during flower induction and dormancy in grapevine buds. Plant Cell Reports. 2009;28(8):1193–1203. doi: 10.1007/s00299-009-0720-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CY, Adams JP, No K, Liang H, Meilan R, Pechanova O, Barakat A, Carlson JE, Page GP, Yuceer C. Overexpression of CONSTANS homologs CO1 and CO2 fails to alter normal reproductive onset and fall bud set in woody perennial poplar. PloS one. 2012;7(9):e45448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia TY, Muller A, Jung C, Mutasa-Gottgens ES. Sugar beet contains a large CONSTANS-LIKE gene family including a CO homologue that is independent of the early-bolting (B) gene locus. J Exper Botany. 2008;59(10):2735–2748. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovsky AE, Rosner MR. Raf kinase inhibitory protein: a signal transduction modulator and metastasis suppressor. Cell Res. 2008;18(4):452–457. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardon F, Damerval C. Phylogenomic analysis of the PEBP gene family in cereals. J Mol Evol. 2005;61(5):579–590. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman H, Kallman T, Lagercrantz U. Early evolution of the MFT-like gene family in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;70(4):359–369. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi W, Liu C, Hou X, Yu H. MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 regulates seed germination through a negative feedback loop modulating ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22(6):1733–1748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.073072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlgren A, Gyllenstrand N, Kallman T, Sundstrom JF, Moore D, Lascoux M, Lagercrantz U. Evolution of the PEBP gene family in plants: functional diversification in seed plant evolution. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(4):1967–1977. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Abe F, Kawahigashi H, Nakazono K, Tagiri A, Matsumoto T, Utsugi S, Ogawa T, Handa H, Ishida H. et al. A wheat homolog of MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 acts in the regulation of germination. Plant Cell. 2011;23(9):3215–3229. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Carpenter R, Copsey L, Vincent C, Rothstein S, Coen E. Control of inflorescence architecture in Antirrhinum. Nature. 1996;379(6568):791–797. doi: 10.1038/379791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Ratcliffe O, Vincent C, Carpenter R, Coen E. Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science. 1997;275(5296):80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin PA, Nilsson O. The multifaceted roles of FLOWERING LOCUS T in plant development. Plant, Cell Environ. 2012;35(10):1742–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge PA. FT, a mobile developmental signal in plants. Curr Biol. 2011;21(9):R374–R378. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amasino R. Seasonal and developmental timing of flowering. Plant J. 2010;61(6):1001–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JH, Miller D, Winter VJ, Banfield MJ, Lee JH, Yoo SY, Henz SR, Brady RL, Weigel D. A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J. 2006;25(3):605–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y, Money T, Bradley D. A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(21):7748–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500932102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin PA, Benlloch R, Bonnet D, Wremerth-Weich E, Kraft T, Gielen JJ, Nilsson O. An antagonistic pair of FT homologs mediates the control of flowering time in sugar beet. Sci. 2010;330(6009):1397–1400. doi: 10.1126/science.1197004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel LE, Wendel JF. Gene duplication and evolutionary novelty in plants. New Phytolog. 2009;183(3):557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, Ma J, Mitros T, Nelson W, Hyten DL, Song Q, Thelen JJ, Cheng J. et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463(7278):178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulin A, Auer PL, Libault M, Schlueter J, Farmer A, May G, Stacey G, Doerge RW, Jackson SA. The fate of duplicated genes in a polyploid plant genome. Plant J. 2013;73(1):143–153. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Wang X, Hu R, Wang Y, Xiao C, Jiang Y, Zhang X, Zheng C, Fu YF. The pattern of Phosphate transporter 1 genes evolutionary divergence in Glycine max L. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, Ichikawa K, Aoki S. Photoperiod-regulated expression of the PpCOL1 gene encoding a homolog of CO/COL proteins in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(4):1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holefors A, Opseth L, Ree Rosnes AK, Ripel L, Snipen L, Fossdal CG, Olsen JE. Identification of PaCOL1 and PaCOL2, two CONSTANS-like genes showing decreased transcript levels preceding short day induced growth cessation in Norway spruce. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47(2):105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Footitt S, Douterelo-Soler I, Clay H, Finch-Savage WE. Dormancy cycling in Arabidopsis seeds is controlled by seasonally distinct hormone-signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(50):20236–20241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116325108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardailsky I, Shukla VK, Ahn JH, Dagenais N, Christensen SK, Nguyen JT, Chory J, Harrison MJ, Weigel D. Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science. 1999;286(5446):1962–1965. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifschitz E, Eviatar T, Rozman A, Shalit A, Goldshmidt A, Amsellem Z, Alvarez JP, Eshed Y. The tomato FT ortholog triggers systemic signals that regulate growth and flowering and substitute for diverse environmental stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(16):6398–6403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601620103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Nonoue Y, Yano M, Izawa T. A pair of floral regulators sets critical day length for Hd3a florigen expression in rice. Nature Gen. 2010;42(7):635–638. doi: 10.1038/ng.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CY, Adams JP, Kim H, No K, Ma C, Strauss SH, Drnevich J, Vandervelde L, Ellis JD, Rice BM. et al. FLOWERING LOCUS T duplication coordinates reproductive and vegetative growth in perennial poplar. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(26):10756–10761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104713108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazakis CM, Coneva V, Colasanti J. ZCN8 encodes a potential orthologue of Arabidopsis FT florigen that integrates both endogenous and photoperiod flowering signals in maize. J Exper Botany. 2011;62(14):4833–4842. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Muszynski MG, Danilevskaya ON. The FT-like ZCN8 Gene Functions as a Floral Activator and Is Involved in Photoperiod Sensitivity in Maize. Plant Cell. 2011;23(3):942–960. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda A, Narumi T, Li T, Kando T, Higuchi Y, Sumitomo K, Fukai S, Hisamatsu T. CsFTL3, a chrysanthemum FLOWERING LOCUS T-like gene, is a key regulator of photoperiodic flowering in chrysanthemums. J Exper Botany. 2012;63(3):1461–1477. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Rong X, Huang X, Cheng S. Recent advances of flowering locus T gene in higher plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(3):3773–3781. doi: 10.3390/ijms13033773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Kaya H, Goto K, Iwabuchi M, Araki T. A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science. 1999;286(5446):1960–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A, Kobayashi Y, Goto K, Abe M, Araki T. TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF) acts as a floral pathway integrator redundantly with FT. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46(8):1175–1189. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini ES, Kramer EM. In the light of evolution: a re-evaluation of conservation in the CO-FT regulon and its role in photoperiodic regulation of flowering time. Frontiers Plant Sci. 2011;2:81. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CH, Wong CE, Singh MB, Bhalla PL. Comparative genomic analysis of soybean flowering genes. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e38250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Liu B, Xia Z, Sato S, Kim BM, Watanabe S, Yamada T, Tabata S, Kanazawa A, Harada K. et al. Two co-ordinately regulated homologs of FLOWERING LOCUS T are involved in the control of photoperiodic flowering in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2010;154(3):1220–1231. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Jia Z, Cao D, Jiang B, Wu C, Hou W, Liu Y, Fei Z, Zhao D, Han T. GmFT2a, a soybean homolog of FLOWERING LOCUS T, is involved in flowering transition and maintenance. PloS one. 2011;6(12):e29238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aloia M, Bonhomme D, Bouche F, Tamseddak K, Ormenese S, Torti S, Coupland G, Perilleux C. Cytokinin promotes flowering of Arabidopsis via transcriptional activation of the FT paralogue TSF. Plant J. 2011;65(6):972–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S, Torti S, Coupland G. Genetic and spatial interactions between FT, TSF and SVP during the early stages of floral induction in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;60(4):614–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SJ, Hong SM, Jung HS, Ahn JH. The cotyledons produce sufficient FT protein to induce flowering: evidence from cotyledon micro grafting in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54(1):119–128. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wang H, Gao P, Xü J, Xü T, Wang J, Wang B, Lin C, Fu Y-F. Analysis of clock gene homologs using unifoliolates as target organs in soybean (Glycine max) J Plant Physiol. 2009;166(3):278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S, Takahashi Y, Kobayashi Y, Monna L, Sasaki T, Araki T, Yano M. Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(10):1096–1105. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashino T, Yamawaki S, Hagui E, Ueoka-Nakanishi H, Nakamichi N, Ito S, Mizuno T. Clock-Controlled and FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT)-Dependent Photoperiodic Pathway in Lotus japonicus I: Verification of the Flowering-Associated Function of an FT Homolog. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77(4):747–753. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledger S, Strayer C, Ashton F, Kay SA, Putterill J. Analysis of the function of two circadian-regulated CONSTANS-LIKE genes. Plant J. 2001;26(1):15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi GH, Deng XW, Holm M. Arabidopsis CONSTANS-LIKE3 is a positive regulator of red light signaling and root growth. Plant Cell. 2006;18(1):70–84. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassidim M, Harir Y, Yakir E, Kron I, Green RM. Over-expression of CONSTANS-LIKE 5 can induce flowering in short-day grown Arabidopsis. Planta. 2009;230(3):481–491. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XF, Wang ZY. Overexpression of COL9, a CONSTANS-LIKE gene, delays flowering by reducing expression of CO and FT in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005;43(5):758–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayama R, Agashe B, Luley E, King R, Coupland G. A circadian rhythm set by dusk determines the expression of FT homologs and the short-day photoperiodic flowering response in Pharbitis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(10):2988–3000. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purwestri YA, Ogaki Y, Tamaki S, Tsuji H, Shimamoto K. The 14-3-3 protein GF14c acts as a negative regulator of flowering in rice by interacting with the florigen Hd3a. Plant Ccell Physiol. 2009;50(3):429–438. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Vincent C, Jang S, Fornara F, Fan Q, Searle I, Giakountis A, Farrona S, Gissot L, Turnbull C. et al. FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science. 2007;316(5827):1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1141752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue):W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin AJ, Cannon SB, Graham MM, Grant D, Shoemaker RC. Changes in twelve homoeologous genomic regions in soybean following three rounds of polyploidy. Plant Cell. 2011;23(9):3129–3136. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.089573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tang H, Debarry JD, Tan X, Li J, Wang X, Lee TH, Jin H, Marler B, Guo H. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(7):e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QJ, Zhou HM, Chen J, Wang XC. Using a modified TA cloning method to create entry clones. Anal Biochem. 2006;358(1):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R, Fan C, Li H, Zhang Q, Fu Y-F. Evaluation of putative reference genes for gene expression normalization in soybean by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10(1):93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Henriques R, Lin SS, Niu QW, Chua NH. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nature protocols. 2006;1(2):641–646. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16(6):735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The information of the BBX or PEBP family. Sheet Gm, At, Vv, Os, Zm, Pp, and Sm showed the information of G. max, A. thaliana, V. vinifera, O. sativa, Z. mays, P. patens and S. moellendorffii, respectively; Sheet Gymnosperm included P. sitchensis, P. radiate, P. pinaster, and P. sylvestris; Sheet Algae included O. lucimarinus, M. pusilla RCC299, M. pusilla CCMP1545, C. subellipsoidea, V. carteri, and C.reinhardtii.

The best match sequences of motifs for the BBX or PEBP family.

Spatio-temporal expressions of GmFTL7. R, root; H, hypocotyl; C, cotyledon; E, epicotyl; U, unifoliolate leaf; S, stem; T1, T2, T3, T4, the first, second, third, and fourth trifoliolate leaf, respectively; F, flower; SAM, the shoot apex (including the apical meristem and immature leaves) at the seedling stage. P1, P2, and P3: seven, fourteen and twenty one days after the onset of flowering, respectively. The geometric means of GmACT11 and GmUKNI transcripts were used as the reference transcript. The bars are means of three replicates, and each replicate represented a pool from at least five plants, and means was formulated as ⊿Ct = Ct(Target gene)-Ct(geometric means of reference genes).

The similarity between soybean and Arabidopsis FT-like genes.

Phenotype of GmTSF3 , GmTSF4 and GmPEBP21 over-expressing in Arabidopsis. A, The phenotype of transgenic lines. B, The rosette leaf number of the transgenic lines at flowering. n showed the total detected lines. Box plot showed total rosette leaf numbers of each line at the beginning of flowering and was generated using GraphPad Prism 5 software. The top of the box is the 75th percentile. The bottom of the box is the 25th percentile. The horizontal line intersecting the box is the median value of the group. Horizontal lines above and below the box represent maximum and minimum values, respectively.

The primers of soybean CO or FT -lineage genes.