Abstract

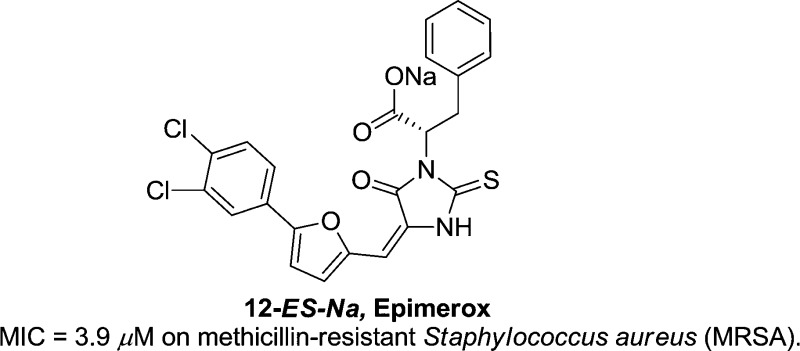

We present the discovery and optimization of a novel series of inhibitors of bacterial UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase (called 2-epimerase in this letter). Starting from virtual screening hits, the activity of various inhibitory molecules was optimized using a combination of structure-based and rational design approaches. We successfully designed and identified a 2-epimerase inhibitor (compound 12-ES-Na, that we named Epimerox), which blocked the growth of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) at 3.9 μM MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) and showed potent broad-range activity against all Gram-positive bacteria that were tested. Additionally a microplate coupled assay was performed to further confirm that the 2-epimerase inhibition of Epimerox was through a target-specific mechanism. Furthermore, Epimerox demonstrated in vivo efficacy and had a pharmacokinetic profile that is consonant with it being developed into a promising new antibiotic agent for treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria.

Keywords: 2-Epimerase inhibitor, antibacterial agent, Gram-positive bacteria, antibiotic-resistant pathogens, stereoisomers

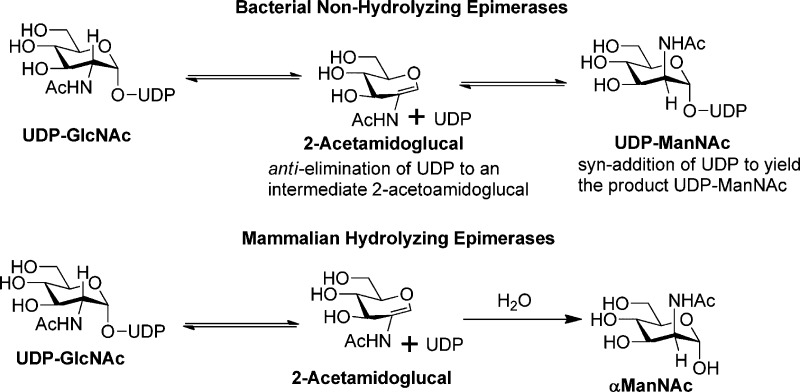

Nonhydrolyzing bacterial UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase (2-epimerase) catalyzes the reversible conversion of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to UDP-N-acetyl-mannosamine (UDP-ManNAc).1,2 The catalytic activity of 2-epimerases produces an activated form of ManNac residues for use in the biosynthesis of a variety of cell surface polysaccharides and the enterobacterial common antigen (ECA), a surface-associated glycolipid common to all members of the Enterobacteriaceae family (Gram-negative bacteria).3 In Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus anthracis, the importance of 2-epimerase in the biosynthesis of polysaccharides is highlighted by the presence of at least two functionally redundant copies of this enzyme.4,5 The structural homology of 2-epimerase to phosphoglycosyl transferases supports the mechanism that the 2-epimerase-catalyzed elimination and readdition of UDP to the glycal intermediate may proceed through a transition state with significant oxocarbenium ion-like character.6 This bacterial 2-epimerase is related to the bifunctional mammalian 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase, a hydrolyzing enzyme that converts UDP-GlcNAc into UDP and ManNAc and phosphorylates the latter into ManNAc 6-phosphate.7,8 The mammalian enzyme catalyzes the rate-limiting step in sialic acid biosynthesis and is a crucial regulator of cell-surface sialylation in humans.9

Bacterial 2-epimerase was characterized as a homodimer in the late 70s and was shown not to require any exogenous cofactors or metal ions for activity. It also was shown that the enzyme was tightly regulated by its own substrate UDP-GlcNAc. No significant UDP-ManNAc epimerization is observed in the absence of substrate UDP-GlcNAc.2,10,11 However, only when trace amounts of UDP-GlcNAc are added does the reaction proceed to equilibrium, thus indicating that UDP-GlcNAc is required for the enzyme to acquire a catalytically competent conformation.

Recently, some of us disclosed the structure of B. anthracis 2-epimerase in the presence of UDP-GlcNAc, which was observed to bind to both the active site of 2-epimerase and to its allosteric site. The structure of B. anthracis 2-epimerase is very similar to the previously determined structure of the homologous E. coli 2-epimerase in complex with UDP (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 1F6D)12 or with UDP-GalNAc (PDB ID 1VGV)13 and the Bacillus subtilis enzyme without substrate (PDB ID 1O6C).13 This was the first time that UDP-GlcNAc was shown to bind both to the allosteric and active site of 2-epimerase. Sequence alignments of 2-epimerases from several bacterial species show that the bacterial UDP-GlcNAc-binding site is conserved and probably unique to the nonhydrolyzing bacterial 2-epimerases. In addition, epimerase gene knockout experiments demonstrated that deletion of one copy of the 2-epimerase gene in B. anthracis (BA5509) had impaired growth compared with the wild-type strains.17 The conservation of the allosteric site residues in the nonhydrolyzing bacterial 2-epimerases (Figure 1) indicates that the allosteric regulatory mechanism, which involves direct interaction between one substrate molecule in the active site and another in the allosteric site, is used exclusively by this class of bacterial enzymes, thus providing a selective way of targeting them, particularly in the case of B. anthracis, for the development of antibacterial agents.

Figure 1.

UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase-catalyzed reactions.

There are some reported inhibitors of 2-epimerases, but most of them are amino sugars, which are mimics or modified GlcNAc/UDP-GlcNAc and strongly bind to the active site of 2-epimerases.14−16 Since their structures have phosphate and amino sugar moieties, they are not drug-like and have poor physicochemical properties in general and only can be used as laboratory tools for inhibition of 2-epimerases.

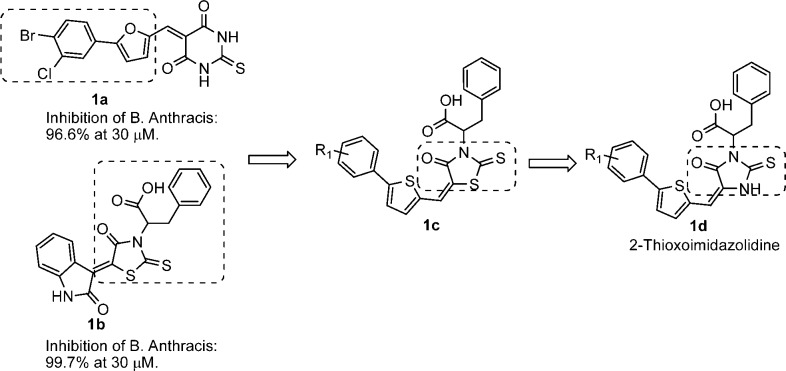

We recently disclosed the identification of a promising 2-epimerase inhibitor (12-ES-Na or Epimerox) with reduced resistance potential.17 Herein, we report in greater depth the development, optimization, and synthesis of Epimerox and several related novel 2-epimerase inhibitors with potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria.17 We initiated our hit-finding efforts by using the 2-epimerase crystal structure as a model for the docking of a large virtual library (∼2 million compounds), composed of in-house and commercially available small molecules, to generate a subset of hits based on calculated binding energies and scores. These hits then were evaluated using a number of in silico physicochemical and ADMET prediction algorithms to determine the degree to which they possessed drug-like properties.22,23 Selected hit compounds (∼100 compounds selected from the 2 million compounds virtual screening libraries) were initially screened using a biochemical enzyme-based assay and a bacterial growth inhibition assay. At a concentration of 30 μM, numerous lead candidates were identified to inhibit bacterial growth by over 50% compared with untreated controls. These lead candidates served as starting points for lead optimization (Scheme 1). Specifically, as shown in Scheme 1, hit compounds 1a and 1b had similar structures, consisting of hydrophobic moieties linked with polar head groups through an ethylene double bond. The lead compound 1c was designed by combining the fragments within the dotted area in hit compounds 1a and 1b. Subsequently, the replacement of sulfur in a rhodanine class18 of thioxothiazolidine 1c generated the thioxoimidazolidine lead compound 1d.

Scheme 1. Design Strategy for 2-Epimerase Inhibitors.

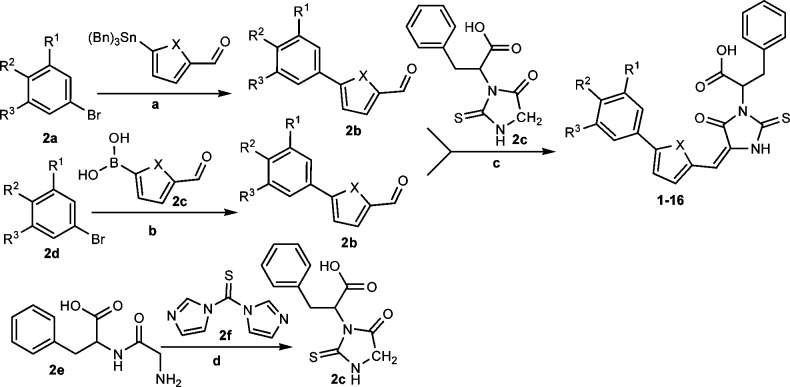

All of the final compounds were prepared using the condensation reaction (Knoevenagel reaction) of substituted thiohydantoins with corresponding aldehydes or ketones.19 The choice of reaction conditions was crucial for the condensation reaction. The most commonly used basic condensation conditions were not useful for the preparation of the targeted molecules because the substituted thiohydantoin was labile under basic conditions and elevated temperatures. Therefore, we developed two kinds of reaction conditions, which were suitable for substituted thiohydantoins condensation reactions (Scheme 2). The starting material thiohydantoin was prepared using the cyclization reaction of thiocarbonyl agent 1,1′-thiocarbonyldiimidazole with dipeptide Gly-dl-Phe.20 The first method employed acetic anhydride as a promoter, and the condensation reaction proceeded readily at 80 °C for 2 h.21 The second method utilized β-alanine, a neutral amino acid, as catalyst, and the condensation reaction provided a good yield of product in 30 min under microwave irradiation.22 During the synthesis of this type of compound, we observed that inorganic bases, such as Na2CO3 and NaHCO3, decomposed either the hydantoin starting materials or products completely at elevated temperature, and no desired product could be detected. The starting material 5-phenyl furanaldehydes were prepared using either Suzuki coupling reactions from the corresponding boronic acids or Stille coupling reactions from stannyl reagents, depending on the availability of the starting materials.

Scheme 2. General Synthetic Route.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Stille coupling; (b) Suzuki coupling; (c) β-alanine, AcOH, 80 °C, 16 h, 54%; (d) THF, reflux 16 h, 66%.

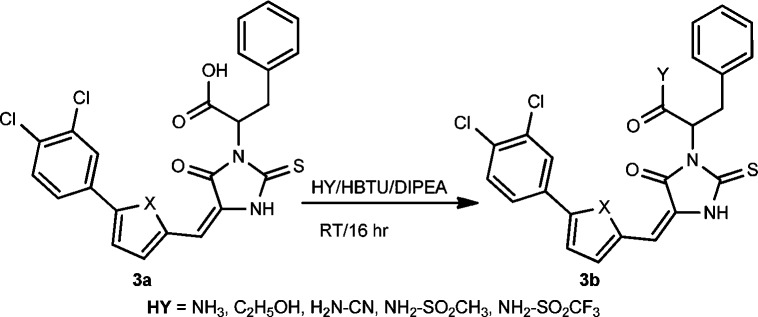

Considering the potential poor permeability of carboxylic acid compounds, we investigated the bioisostere of carboxylic acid to optimize the lead compound’s physicochemical properties and potency (Scheme 3). The bioisosteric compounds of carboxylic acid were prepared by coupling carboxylic acid with the corresponding amine, alcohol, or sulfonamide, and the reaction was promoted by HBTU in the presence of DIPEA. Ammonium chloride instead of ammonia was utilized as an amination reagent to prepare the primary amide compound. The condensation reaction of methanesulfonyl amide and trifluoromethanesulfonyl amide with acid also afforded good yields of N-sulfonyl amide products under the same reaction conditions.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Bioisosteres of Carboxylic Acid.

First, we investigated the effect of substituents on the terminal phenyl ring. In the following order, -OCH3, -H, -F, -Cl, -Br, -I, and -OCF3, the electron-withdrawing group increased the potency and the electron-donating group decreased the potency, suggesting that the electron-withdrawing group is beneficial for binding to 2-epimerase (Table 1).

Table 1. Compound Structure and Antibiotic Activity against B. anthracisa and MRSA.

|

B.anthracis inhibition percentageb |

S.

aureus (MRSA) inhibition percentageb |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R2 | X | 30 μm | 10 μm | 3 μm | 30 μm | 10 μm | 3 μm |

| 1 | -H | -OCH3 | S | 100 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

| 2 | -H | -F | S | 100 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 20 | 20 |

| 3 | -H | -Cl | S | 100 | 100 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | -H | -Br | S | 100 | 100 | 80 | 90 | 90 | 20 |

| 5 | -H | -H | O | 20 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| 6 | -H | -Cl | O | 100 | 70 | 0 | 90 | 20 | 10 |

| 7 | -Cl | -H | O | 90 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | -H | -Br | O | 100 | 100 | 70 | 90 | 90 | 10 |

| 9 | -H | -I | O | 100 | 100 | 50 | 90 | 90 | 0 |

| 10 | -H | -OCF3 | O | 100 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 0 |

B. anthracis Sterne strain.

Each value is the mean of at least three experiments, and the standard deviation is less than 10% of the mean.

The bromide group exhibited optimal potency. Iodo and trifluoromethoxyl groups exhibited slightly weaker activity compared with the bromide compound. The furan and thiophene linkers showed similar activity and indicated that both an oxygen and sulfur atom at this position could be tolerated well by 2-epimerase.

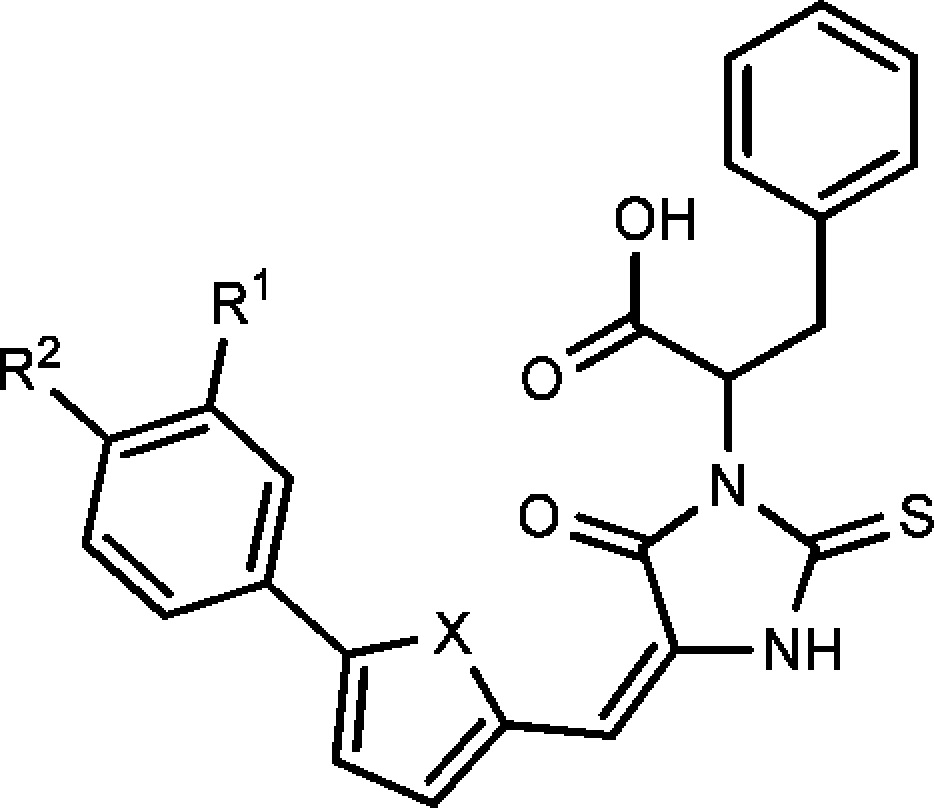

Since the electron-withdrawing group at the terminal phenyl group enhanced the potency, we also explored dihalogen substituted compounds. However, we found that the potency of dihalogen substituted compounds was related to the five-membered ring linker. As shown in Table 2, the furan-linked dihalogen compounds have significantly improved activity in comparison with the corresponding monohalogen substituted compounds. In contrast, the thiophene-linked compounds have decreased activity relative to the corresponding monohalogen substituted compounds.

Table 2. Compound Structure and Antibiotic Activity against B. anthracisa and MRSA.

|

B.anthracis inhibition percentageb |

S. aureus (MRSA) inhibition percentageb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R2 | R3 | X | 30 μm | 10 μm | 3 μm | 30 μm | 10 μm | 3 μm |

| 11 | -Cl | -Cl | -H | S | 90 | 110 | 0 | 40 | 10 | 10 |

| 12 | -Cl | -Cl | -H | O | 110 | 110 | 110 | 100 | 90 | 20 |

| 13 | -Cl | -Br | -H | S | 90 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 10 | |

| 14 | -Cl | -Br | -H | O | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 20 |

| 15 | -Cl | -H | -Cl | O | 100 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| 16 | -Cl | -OCH3 | -H | O | 100 | 30 | 0 | 80 | 10 | 10 |

B. anthracis Sterne strain.

Each value is the mean of at least three experiments, and the standard deviation is less than 10% of the mean.

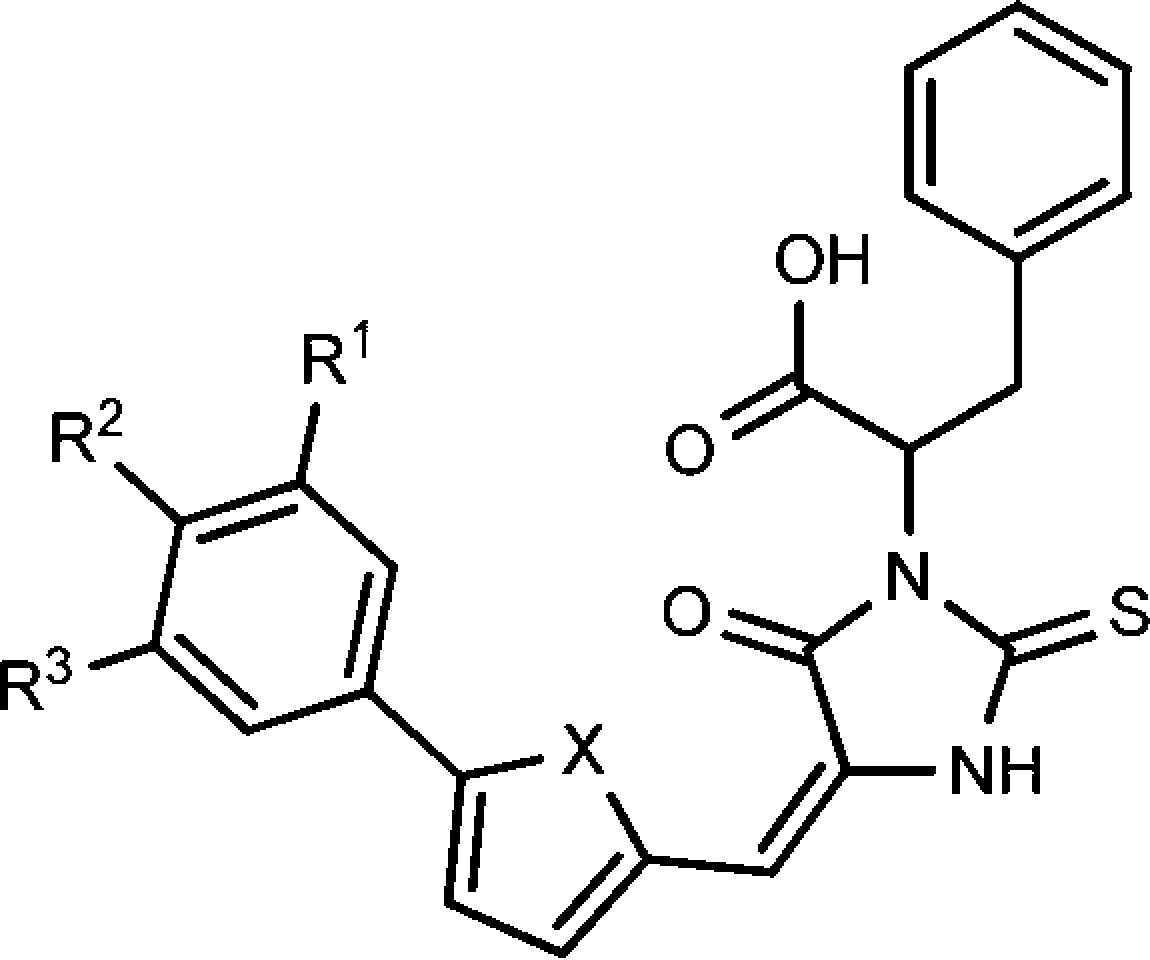

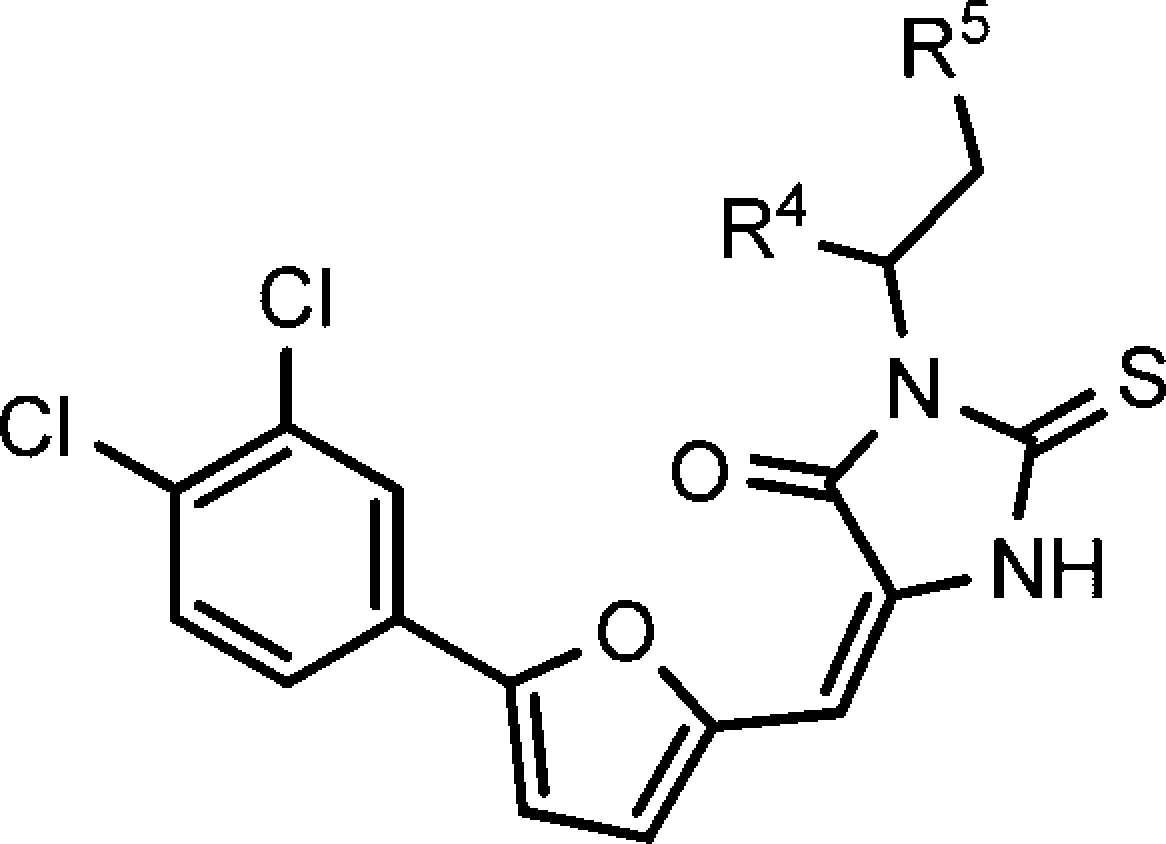

To improve compound’s potency and physicochemical properties, we investigated several commonly used bioisosteres of carboxylic acid, including amide, ethyl ester, cyano amide, methanesulfonylamide, and trifluoro-methanesulfonylamide. We synthesized the above-mentioned bioisosteres of carboxylic acid and found that only the ethyl ester compound aborted the activity (Table 3). Trifluoromethanesulfonylamide exhibited the best activity and showed activity similar to that of the parent compound. As shown in compounds 17 and 23, the replacement of phenyl with methyl reduced potency significantly and further indicated that the ππ-stacking interaction of phenyl is required for the inhibition potency.

Table 3. Compound Structure and Antibiotic Activity against B. anthracisa and MRSA.

|

B.anthracis inhibition percentageb |

S.

aureus (MRSA) inhibition percentageb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R4 | R5 | 30 μm | 10 μm | 3 μm | 30 μm | 10 μm | 3 μm |

| 12 | -COOH | -Ph | 110 | 110 | 110 | 100 | 90 | 20 |

| 17 | -COOH | -CH3 | 90 | 100 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | -CONH2 | -Ph | 90 | 90 | 20 | 60 | 30 | 0 |

| 19 | -CO2Et | -Ph | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 20 | -NHCN | -Ph | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | -NHSO2CH3 | -Ph | 90 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 30 | 0 |

| 22 | -NHSO2CF3 | -Ph | 100 | 100 | 70 | 90 | 80 | 0 |

| 23 | -NHSO2CH3 | -CH3 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

B. anthracis Sterne strain.

Each value is the mean of at least three experiments, and the standard deviation is less than 10% of the mean.

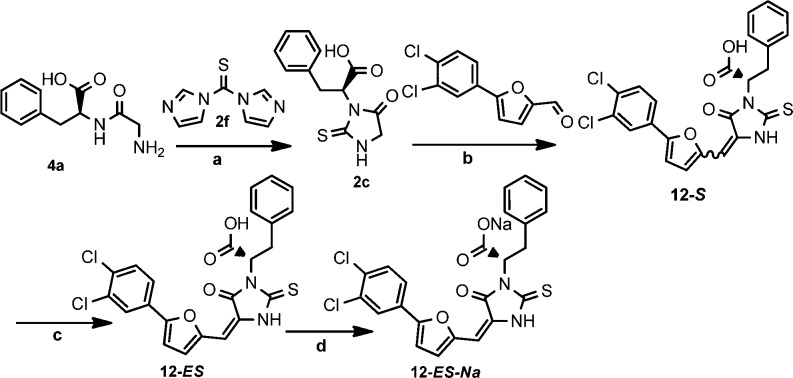

Considering that compound 12 had the most potent inhibitory activity, we also investigated the effect of E/Z configuration of the double bond and R/S chirality of the carboxylic acid on growth inhibition activity. NMR and HPLC analysis of compound 12 showed that the major isomer is the E isomer with 90% ratio. The E-isomer was successfully separated by recrystallization in DCM-CH3OH cosolvent. However, the separation of Z-isomer by recrystallization failed after various conditions and solvents were tried (Scheme 4). Therefore, the Z-isomer was isolated using preparative HPLC. After obtaining both -E and -Z isomers of compound 12, we evaluated their growth inhibitory activity and found no significant difference between these isomers. Each of the R/E and S/E isomers were obtained by beginning with enantiomerically pure starting material Gly-d-Phe and Gly-l-Phe, respectively. However, all four isomers showed equivalent inhibitory activity (6.8 μM MIC) on strains of S. aureus 13709 and B. subtilis 19659. Furthermore, we found that the sodium salt of compound 12 (12-ES) (Scheme 4) had equivalent growth inhibitory potency but with much better aqueous solubility, a feature that might expedite formulation and in vivo studies. We also evaluated the chemical stability of compound 12-ES-Na and found that it was very stable. We did not observe any isomerization or decomposition for compound 12-ES-Na at pH = 10 aqueous solution after 3 days. No isomerization was detected by HPLC or NMR.

Scheme 4. Optimized Synthetic Route to Compound 12-ES-Na.

Reagents and conditions: (a) THF, RT, 16 h, 43%; (b) β-alanine, AcOH, 80 °C, 16 h, 54%; (c) DCM, CH3OH, hexane, recrystallization; (d) Na2CO3, DCM, CH3OH, and DCM, recrystallization, 83%.

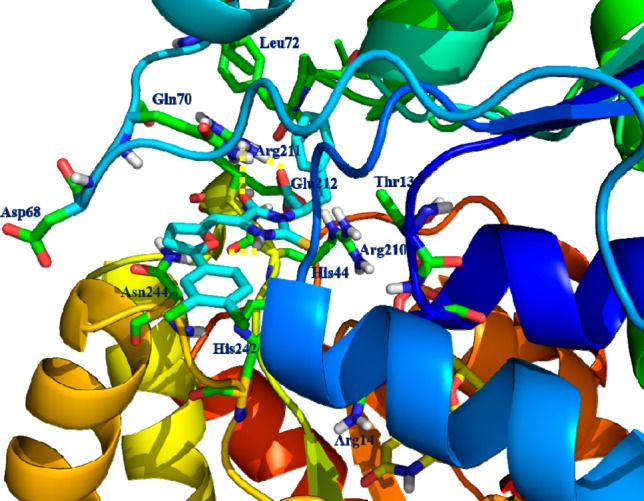

Beginning with a 2 million compound virtual screening library,23,24 hit-to-lead optimization and docking experiments were performed using a crystal structure of 2-epimerase (PDB ID 3BEO) in complex with Epimerox17 suggesting that compound 12-ES bound in the allosteric binding site of 2-epimerase as shown in Figure 2. Hydrogen binding interaction with the Arg211 and proximity to the Arg210 residue involved in allosteric regulation is the key for the activities of compound 12-ES. In designing thioxothiazolidine replacements, we chose the allosteric binding thioxothiazolidine core to thioxoimidazolidine as well as the substitution of electron-withdrawing groups at the 2-aryl that oriented favorably with the histidine His242 and His209 through charge–charge contacts. Additionally, our lead optimization efforts toward compound 12-ES established the importance of occupying the vector adjacent to the allosteric site; the phenyl propionate πιπι-stacking interactions with Tyr134 for overall stability and 2-epimerase activity.

Figure 2.

Docking model of the complex formed between compound 12-ES and the 2-epimerase crystal structure model (PDB ID 1F6D) of the allosteric binding site. The critical residues involved in H-bonding interaction were shown as solid yellow dashed lines.

The incorporation of this thioxoimidazolidine appeared to satisfy structural requirements for 2-epimerase binding over the promiscuous 2-thioxothiazolidin moiety and was one of the major considerations in the design of compound 12 and its analogues. The 2-thioxoimidazolidine–NH participated in hydrogen bonding interaction with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Arg210. Lastly, the carboxylic acid moiety occupied Arg211 region of the active site and involved in strong hydrogen bonding interactions with −NH of Arg211. Further we modeled the compound 12 R/E and S/E isomers and observed its effect within the allosteric site of the 2-epimerase crystal structure. The position and orientations of each of the isomers revealed that there is no isomeric effect on binding of compound 12 or its thioxoimidazolidine series of compounds and further supported the conserved H-bonding interaction with Arg211 and synergy with the growth inhibitory activities. This has provided a fixable substitution vector to modulate physicochemical and ADME properties such as pKa23 and for the preparation few bioisosteres of carboxylic acid, such as −NHSO2CH3, NHSO2CF3, and NHCN groups were explored because of their favorable physicochemical properties and their synthetic tractability presented in Scheme 4 and Table 3.

Inhibitory activity of compound 12-ES-Na against B. anthracis UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase was tested in a previously described coupled assay that employs UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase10 giving a Ki of 82 μM under physiological conditions (Figure S1, Supporting Information). On the basis of the in vitro potency of compound 12-ES-Na (or Epimerox) on B. anthracis (Sterne) and MRSA, we further evaluated 12-ES-Na by testing a panel of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains. Table 4 indicates that the sodium salt, 12-ES-Na, had good activity against the panel of Gram-positive bacteria, but not significant potency against Gram-negative strains.

Table 4. Spectrum of Antibacterial Activity for Compound 12-ES-Na.

| strain | Gram ± | MIC μMa | strain | Gram ± | MIC μMa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | negative | >25 | S. aureus 6538 | positive | 7.8 |

| S. aureus | positive | 3.91 | S. aureus 13709 | positive | 7.8 |

| S. enterica | negative | >25 | S. epidermidis 13518 | positive | 2.0 |

| E. coli | negative | >25 | S.pyogenes 19615 | positive | 3.9 |

| C. albicans | positive | >25 | S. agalacatiae 12386 | positive | 3.9 |

| S. epidermidis | positive | 3.91 | S. pneumoniae 6301 | positive | 3.9 |

| S. marcescens | negative | >25 | S. mutans 25175 | positive | 3.9 |

| S. sonnei | negative | >25 | E. faecalis 19433 | positive | 15.6 |

| B. atrophaeus | positive | 7.8 | E. faecium 6569 | positive | 15.6 |

| A. baumannii | negative | >25 | B. subtilis 19659 | positive | 7.8 |

| P. mirabilis | negative | >25 | S. equi 6939 | positive | 7.8 |

MICs were determined in triplicate on three different days using a broth microdilution method; no variation was observed in MIC values.

The compound 12-ES-Na showed the most desirable potency profile and was further evaluated to assess pharmacokinetic properties in mice. The objective of the pharmacokinetic study was to assess the exposure of CD-1 female mice to 12-ES-Na when the test compound was administered intraperitoneally (i.p). Mouse pharmaco-kinetic studies showed a strong dose response with reasonably linear kinetics with increasing dose. Lead compound 12-ES-Na, had a reasonable rodent PK profile with a half-life of 2–3 h and a clearance of ∼100 mL/h/kg. The AUC was more than 200-fold the MIC, and time of concentration above MIC was more than 10 h following a single dose (Table 5). There was no mortality and no significant clinical observations were noted when the dosage was below 100 mg/kg.

Table 5. Pharmacokinetic Properties of Compound 12-ES-Na on CD-1 Female Mice.

| group | dose (mg/kg) | tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | half-life (h) | VZ (mL/kg) | Cl (ML/h/kg) | AUC (ng.h/mL) | time (h) above MIC (2000 ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 0.08 | 68000 | 2.4 | 500 | 140 | 170000 | 10.6 |

| 2 | 50 | 0.5 | 140000 | 2.3 | 340 | 100 | 480000 | 14.6 |

| 3 | 100 | 0.08 | 490000 | 2.2 | 180 | 55 | 1800000 | 19.4 |

| 4 | 50 (BID) | 3.08 | 320000 | 3.4 | 240 | 47 | 1050000 | 18.3 |

The in vivo efficacy for 12-ES-Na was demonstrated in survival studies following administration of B. anthracis (Sterne). Compound 12-ES-Na was evaluated for its ability to prevent mortality in mice infected with a lethal dose of B. anthracis (Sterne). Compound 12-ES-Na was dissolved completely in propylene glycol (customarily used and approved by the FDA for use in injectable) and then could be diluted further in PBS, thereby allowing the undertaking of additional preclinical trials in mice. A full description of this experiment was published and it showed that the epimerase inhibitor 12-ES-Na can effectively block Bacillus anthracis infection in mice.17

In conclusion, we developed a series of putative inhibitors of the bacterial enzyme 2-epimerase. All of these 2-epimerase inhibitor compounds blocked the growth of MRSA at low μM MIC as well as growth of all other tested Gram-positive bacterial strains. On the basis of its PK and efficacy profile, compound 12-ES-Na (Epimerox) appears to be a promising new antibacterial agent for the treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants 1U19AI056510, AI057472, and 2U54AI057153 to Dr. Vincent A. Fischetti from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and early discovery and development support from Astex Pharmaceuticals.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- UDP

uridine diphosphate

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- ADMET

absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity

- HBTU

N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- AUC

area under the concentration curve

- DCM

dichloromethylene

- PK

pharmacokinetic

Supporting Information Available

Full experimental procedures and characterization for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

∥ Avacyn Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Teaneck, New Jersey 07666, United States.

Author Present Address

⊥ Division of Oncology of School of Medicine and Center for Investigational Therapeutics at Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, 2000 Circle of Hope, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, United States.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Kawamura T.; Kimura M.; Yamamori S.; Ito E. Enzymatic formation of uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-d-mannosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 1978, 253, 3595–3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura T.; Ishimoto N.; Ito E. Enzymatic synthesis of uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-d-mannosaminuronic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 8457–8465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn H. M.; Meier-Dieter U.; Mayer H. ECA, the enterobacterial common antigen. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 4, 195–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser K. B.; Bhasin N.; Deng L.; Lee J. C. Staphylococcus aureus cap5P encodes a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase with functional redundancy. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 4818–4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read T. D.; Peterson S. N.; Tourasse N.; Baillie L. W.; Paulsen I. T.; et al. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature 2003, 423, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M. E. Understanding nature’s strategies for enzyme-catalyzed racemization and epimerization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderlich S.; Stasche R.; Zeitler R.; Reutter W. A bifunctional enzyme catalyzes the first two steps in N-acetylneuraminic acid biosynthesis of rat liver. Purification and characterization of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 24313–24318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasche R.; Hinderlich S.; Weise C.; Effertz K.; Lucka L.; Moormann P.; Reutter W. A bifunctional enzyme catalyzes the first two steps in N-acetylneuraminic acid biosynthesis of rat liver. Molecular cloning and functional expression of UDP-N-acetyl-glucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 24319–24324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler O. T.; Hinderlich S.; Langner J.; Schwartz-Albiez R.; Reutter W.; Pawlita M. UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase: a regulator of cell surface sialylation. Science 1999, 284, 1372–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan P. M.; Sala R. F.; Tanner M. E. Eliminations in the reactions catalyzed by UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 10269–10277. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel J.; Tanner M. E. Active site mutants of the non-hydrolyzing UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1700, 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. E.; Mosimann S. C.; Tanner M. E.; Strynadka N. C. J. The structure of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase reveals homology to phosphoglycosyl transferases. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 14993–15001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger J.; Sauder J. M.; Adams J. M.; Antonysamy S.; Bain K.; Bergseid M. G.; Buchanan S. G.; Buchanan M. D.; Batiyenko Y.; Christopher J. A.; Emtage S.; Eroshkina A.; Feil I.; Furlong E. B.; Gajiwala K. S.; Gao X.; He D.; Hendle J.; Huber A.; Hoda K.; Kearins P.; Kissinger C.; Laubert B.; Lewis H. A.; Lin J.; Loomis K.; Lorimer D.; Louie G.; Maletic M.; Marsh C. D.; Miller I.; Molinari J.; Muller-Dieckmann H. J.; Newman J. M.; Noland B. W.; Pagarigan B.; Park F.; Peat T. S.; Post K. W.; Radojicic S.; Ramos A.; Romero R.; Rutter M. E.; Sanderson W. E.; Schwinn K. D.; Tresser J.; Winhoven J.; Wright T. A.; Wu L.; Xu J.; Harris T. J. Structural analysis of a set of proteins resulting from a bacterial genomics project. Proteins 2005, 60, 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawi S.; Hinderlich S.; Reutter W.; Giannis A. Sialic acids: Synthesis and biochemical properties of reversible inhibitors of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4366–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz F.; Blume A.; Hinderlich S.; Reutter W.; Schmidt R. R. C-glycosidic UDP-GlcNAc analogues as inhibitors of UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 15, 3304–3312. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz F.; Reiner M.; Blume A.; Reutter W.; Schmidt R. R. Novel UDP-glycal derivatives as transition state analogue inhibitors of UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 665–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch R.; Pelzek A. J.; Raz A.; Euler C. W.; Ryan P. A.; Winer B. Y.; Farnsworth A.; Bhaskaran S. S.; Stebbins C. E.; Xu Y.; Clifford A.; Bearss D. J.; Vankayalapati H.; Goldberg A. R.; Fischetti V. A. Use of a bacteriophage lysin to identify a novel target for antimicrobial development. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendgen T.; Steuer C.; Klein C. D. Privileged scaffolds or promiscuous binders: a comparative study on rhodanines and related heterocycles in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londhe A.; Gupta B.; Khatri P.; Pardasani P.; Pardasani R. T. Comprehensive synthesis and biological assay of spiro thioisatin derivatives. Indian J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2005, 15, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Charton J.; Gassiot A. C.; Girault-Mizzi S.; Debreu-Fontaine M.-A.; Melnyk P.; Sergheraert C. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of Tic-hydantoin derivatives as selective σ1 ligands. Part 1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4833–4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui Y.-H.; Cao L.-H. Synthesis of 5-(chromon-3-ylmethylidene)-3-arylthiohydantoin. Youji Huaxue 2006, 26, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Prout F. S. Amino acid catalysis of the Knoevenagel reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1953, 18, 928–933. [Google Scholar]

- QikProp, 2009. http://schrodinger.com.

- pKa Plugin ionization equilibrium partial charge disstribtion, 2011. http://cemaxon.com/pKa.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.