Abstract

Up to 5% of all small cell carcinomas develop at extrapulmonary sites. Primary small cell carcinomas originating in the kidney are extremely rare neoplasms. Here we report a case of primary small cell carcinoma of the kidney. A nephrectomy was performed on a 52-year-old female patient to remove a large tumor located in the right kidney. The histology and immunohistochemistry of the resected tumor revealed a pure small cell carcinoma with invasion into the renal capsule. The patient received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin. The patient has been monitored with regular check ups and remains stable with no recurrence at 28 months after the initial diagnosis.

Keywords: Small cell carcinoma, Kidney, Chemotherapy, Nephrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Small cell carcinomas are most commonly seen in the lung, but rare cases of extrapulmonary sites have also been reported and include: the esophagus, larynx, nasal cavity, gastrointestinal tract, uterine cervix, bladder, and breast1, 2). Small cell carcinoma of the kidney is an uncommon and reportedly a very aggressive neoplasm; there is no standard treatment protocol available due to the small number of cases described. The median survival rate is reported as up to 8 months3). As in cases of pulmonary small cell carcinoma, chemotherapy may lead to an improved outcome in patients with extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. We report a patient with primary small cell carcinoma of the kidney; this patient was treated with nephrectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin. The patient remains disease free at 28 months following the initial diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old woman had a 2-week history of right flank pain and intermittent hematuria with iron deficiency anemia. Physical examination of the patient was unremarkable, except for an abdominal mass and CVA tenderness. Laboratory data were as follows: white blood count 8,280/µL, platelet 346,000/µL, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL, MCV 74.3 fl, MCH 24.4 pg, MCHC 32.8 g/dL; serum blood urea nitrogen 12.7 mg/dL, serum creatinine 0.89 mg/dL. Urinalysis showed microscopic hematuria. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a relatively well defined, large heterogeneous tumor in the right kidney (Figure 1). CT scans of the brain and chest, as well as a bone scan were carefully examined to look for signs of metastatic disease. There were no evident metastases at regional lymph nodes or at any distant organs. The preoperative impression was a renal cell carcinoma; the patient underwent a right radical nephrectomy. Macroscopically, a very large mass measuring 10×15 cm, from the right kidney, was identified (Figure 2). Cut sections were grey-yellow in color and contained bloody and serosanguinous fluid. The tumor penetrated the capsule, but there was no infiltration into the renal pelvis, hilus of the kidney or adjacent lymph nodes. Histological examination revealed a pure small cell carcinoma with scant cytoplasm and stippled nuclear chromatin (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical stains revealed that the tumor cells were strongly positive for synaptophysin, weakly positive for chromogranin, and negative for S-100, leukocyte common antigen (Figure 3B, 3C). We concluded that this case represented a pure small cell carcinoma of the kidney. Postoperatively, the patient received six courses of adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of etoposide and cisplatin. Upon completion of the chemotherapy, all oncological investigations, including abdominopelvic CT and chest X-ray, revealed no evidence of recurrence. Outpatient follow-up of laboratory and radiographic studies were performed at regular intervals. The patient is currently well without any evidence of recurrence at 28 months following the primary diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen reveals a large, complex heterogeneous mass in the right kidney without retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.

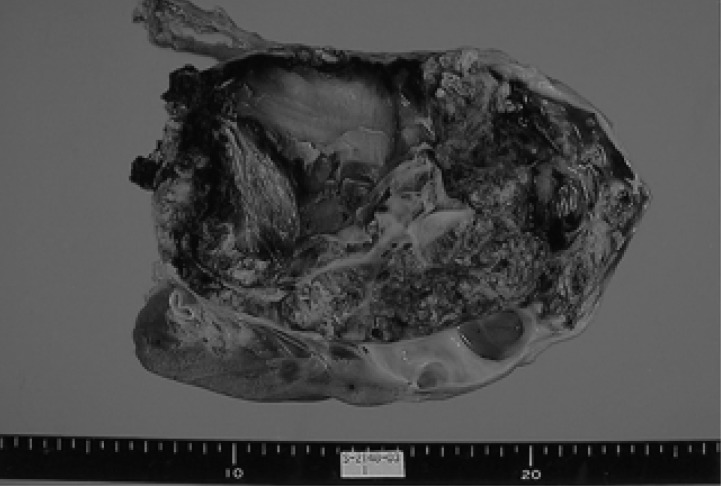

Figure 2.

The resected tumor of the right kidney measured 10×15.5 cm in size.

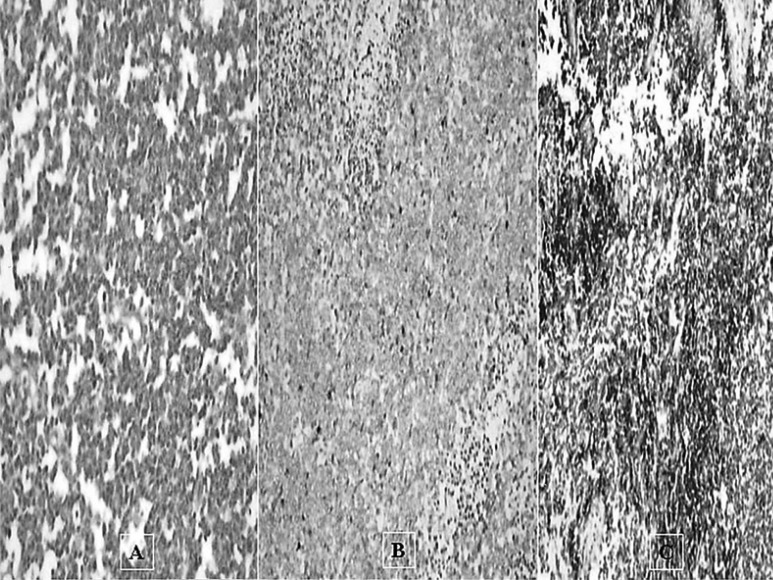

Figure 3.

Biopsy sample pathology (A) High power magnification of the small cell carcinoma portion (H&E stain ×200). Note that the tumor cells are often oat shapedomatin with inconspicuous nucleoli. (B) The tumor cells are negative for LCA immunostaining, (C) positive for Synaptophysin immunostaining.

DISCUSSION

Small cell carcinomas are most commonly identified in the lungs; these tumors have also been reported to originate from a number of extrapulmonary sites such as: colorectal, esophagus, pancreas, bladder, uterine cervix, larynx, and salivary glands1, 2). Small cell carcinomas of the genitourinary tract have most commonly been reported to develop in the urinary bladder. Primary small cell carcinomas originating in the kidneys are extremely rare3).

A review of patients with small cell carcinoma of the kidney revealed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, and showed that women are more commonly affected than men3). There are no pathognomic clinical findings or symptoms that suggest the presence of this abnormality. Symptoms, as with other cancers of the kidney, are fundamentally characterized by abdominal pain and hematuria. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom, affecting nearly 70% of patients. The next most common clinical manifestations are hematuria (45%) followed by flank mass (15%) and weight loss (10%).

The diagnosis of a small cell carcinoma, whether of pulmonary or extrapulmonary origin, can be established by light microscopic and immunohistochemical examination of tumor tissue. The tumor can be further classified into a pure or combined type. In the literature, Masuda et al4) reported 18 cases of small cell carcinoma of the kidney; more than half of these cases were associated with transitional cell carcinoma.

Patients with small cell carcinoma of the kidney can be clinically classified using a method similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung5). Limited disease is defined as a tumor localized to the organ of origin, and regional lymph nodes easily included within one radiation therapy treatment portal; any evidence of disease beyond this is classified as extensive disease. Majhail et al3) reviewed the literature based on this classification and found that limited stage disease was present in 10 of 18 patients available for evaluation.

Although the clinical behavior of these tumors can vary based on their origin, extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas are invariably aggressive, with a median survival time of less than one year; they have a tendency to develop early nodal and disseminated metastatic disease6). Because of the unfavorable prognosis, multimodal therapy has been used increasingly to prolong life. Multimodal therapy typically includes chemotherapy and radiotherapy as well as possible surgery depending on the severity of the disease and its primary site. Chemotherapeutic regimens used in treating extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas are the same as those employed in small cell carcinomas of the lung. The use of platinum based adjuvant chemotherapy may be a reasonable approach to these patients in an effort to decrease the chance of systemic recurrence. The severity of disease at diagnosis represents the most sensitive predictor of survival. However, localized treatments should not be used, as a single modality, for the treatment of limited disease.

In conclusion, we report a case of an unusual primary small cell carcinoma of the kidney. The patient is currently well without any evidence of recurrence at 28 months following the primary diagnosis. Our results suggest that after complete resection of the tumor, chemotherapy should be provided due to the high incidence of occult metastases. The outcome of our patient suggests that cisplatin based chemotherapy, following surgical treatment of a small cell carcinoma of the kidney, may improve the currently dismal prognosis of similar cases.

Footnotes

This study was supported by research funds from Chosun Univsersity, 2004.

References

- 1.Kim JH, Lee SH, Park J, Kim HY, Lee SI, Nam EM, Park JO, Kim K, Jung CW, Im YH, Kang WK, Lee MH, Park K. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma: a single institution experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:250–254. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson RL, Weiland LH. Undifferentiated small cell carcinomas in extrapulmonary sites. Semin Oncol. 1982;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majhail NS, Elson P, Bukowski RM. Therapy and outcome of small cell carcinoma of the kidney: report of two cases and a systematic review of the literature. Cancer. 2003;97:1436–1441. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda T, Oikawa H, Yashima A, Sugimura J, Okamoto T, Fujioka T. Renal small cell carcinoma (neuroendorine carcinoma) without features of transitional cell carcinoma. Pathol Int. 1998;48:412–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galanis E, Frytak S, Lloyd RV. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:1729–1736. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970501)79:9<1729::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sengoz M, Abacioglu U, Salepci T, Eren F, Yumuk F, Turhal S. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma: multimodality treatment results. Tumori. 2003;89:274–277. doi: 10.1177/030089160308900308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]