Significance

Molecular electronics, with molecules functioning as the basic building blocks of circuits, is considered by some to be one of the contenders for next-generation electronics. Radical molecules are interesting because a quantum phenomenon, the Kondo effect, involving the radical’s unpaired electron and its spin, has the potential to enhance and control conductance. Examples of molecular Kondo are known experimentally in geometries including mechanical break junctions and scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS), but so far it has not been possible to make accurate theoretical predictions. Here we predict the Kondo effect expected for the simplest molecular radical, nitric oxide, on a gold surface. Subsequently we verify that experimentally by STS. Both agreements and discrepancies offer a quantitative lesson of considerable future use.

Keywords: nanocontacts, Anderson impurity model, ballistic conductance, phase shift

Abstract

Molecular contacts are generally poorly conducting because their energy levels tend to lie far from the Fermi energy of the metal contact, necessitating undesirably large gate and bias voltages in molecular electronics applications. Molecular radicals are an exception because their partly filled orbitals undergo Kondo screening, opening the way to electron passage even at zero bias. Whereas that phenomenon has been experimentally demonstrated for several complex organic radicals, quantitative theoretical predictions have not been attempted so far. It is therefore an open question whether and to what extent an ab initio-based theory is able to make accurate predictions for Kondo temperatures and conductance lineshapes. Choosing nitric oxide (NO) as a simple and exemplary spin 1/2 molecular radical, we present calculations based on a combination of density functional theory and numerical renormalization group (DFT+NRG), predicting a zero bias spectral anomaly with a Kondo temperature of 15 K for NO/Au(111). A scanning tunneling spectroscopy study is subsequently carried out to verify the prediction, and a striking zero bias Kondo anomaly is confirmed, still quite visible at liquid nitrogen temperatures. Comparison shows that the experimental Kondo temperature of about 43 K is larger than the theoretical one, whereas the inverted Fano lineshape implies a strong source of interference not included in the model. These discrepancies are not a surprise, providing in fact an instructive measure of the approximations used in the modeling, which supports and qualifies the viability of the density functional theory and numerical renormalization group approach to the prediction of conductance anomalies in larger molecular radicals.

Electron transport through molecules adsorbed on metallic surfaces or suspended between metal leads is the basic ingredient of molecular electronics (1–3). Because the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals rarely lie close to the Fermi energy, electrons must generally tunnel through the molecule, making the zero bias conductance much smaller than  , the conductance quantum, whenever gating is not easily achieved, as is the case in mechanical break junctions and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). That problem does not persist for molecular radicals, where one or more molecular orbitals are singly occupied, generally resulting in a net spin. When brought into contact with a metal, the radical’s spin is Kondo screened (4), leading to a zero bias conductance that may be of order G0 with a Fano-like anomaly below the Kondo temperature TK (5, 6) and no need for gating. One reason for practical interest in such anomalies is the sensitivity of the conductance to external control parameters such as magnetic fields and mechanical strain (7). Several molecular contacts have been studied (8), involving both adsorbed (9–16) and contact-bridging (7, 17–19) molecules. None so far involved a radical molecule that is both simple and spin 1/2, and the Kondo anomalies were not predicted from first principles, ahead of experiment. Both the intrinsic complexity of the contact between a large molecular radical and a metal and the unavailability of quantitatively tested ab initio electronic structure-based approaches to Kondo conductance have so far restricted the theoretical work to the role of a posteriori support of STM and break junction zero bias anomaly data. It is therefore important to achieve a first-principles predictive capability of Kondo conductance anomalies across molecular radicals and ascertain its reliability. To that end, we put to work a density functional theory and numerical renormalization group (DFT+NRG) method devised and implemented earlier in our group (20–22) but not yet verified by experiment. Although other strategies with similar goals have also been proposed in refs. 23–26, we can now demonstrate the predictive power as well as the limitations of our procedure in a specific test case where direct comparison with experiment is possible.

, the conductance quantum, whenever gating is not easily achieved, as is the case in mechanical break junctions and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). That problem does not persist for molecular radicals, where one or more molecular orbitals are singly occupied, generally resulting in a net spin. When brought into contact with a metal, the radical’s spin is Kondo screened (4), leading to a zero bias conductance that may be of order G0 with a Fano-like anomaly below the Kondo temperature TK (5, 6) and no need for gating. One reason for practical interest in such anomalies is the sensitivity of the conductance to external control parameters such as magnetic fields and mechanical strain (7). Several molecular contacts have been studied (8), involving both adsorbed (9–16) and contact-bridging (7, 17–19) molecules. None so far involved a radical molecule that is both simple and spin 1/2, and the Kondo anomalies were not predicted from first principles, ahead of experiment. Both the intrinsic complexity of the contact between a large molecular radical and a metal and the unavailability of quantitatively tested ab initio electronic structure-based approaches to Kondo conductance have so far restricted the theoretical work to the role of a posteriori support of STM and break junction zero bias anomaly data. It is therefore important to achieve a first-principles predictive capability of Kondo conductance anomalies across molecular radicals and ascertain its reliability. To that end, we put to work a density functional theory and numerical renormalization group (DFT+NRG) method devised and implemented earlier in our group (20–22) but not yet verified by experiment. Although other strategies with similar goals have also been proposed in refs. 23–26, we can now demonstrate the predictive power as well as the limitations of our procedure in a specific test case where direct comparison with experiment is possible.

Seeking a molecular radical Kondo system of the utmost simplicity and stimulated by the experimentally observed Kondo screening of the S = 1 radical O2 (12), we singled out nitric oxide (NO) as the smallest and simplest  radical molecule that might display a Kondo conductance anomaly in an adsorbed state. We have therefore applied our theoretical program to STM conductance of the NO radical adsorbed on the Au(111) surface. NO is an interesting test case, in the past only qualitatively considered as a prototype of radical-surface Kondo interactions (27, 28), whereas recently it has been used instead to quench the spin state of larger molecular radicals such as porphyrins (29).

radical molecule that might display a Kondo conductance anomaly in an adsorbed state. We have therefore applied our theoretical program to STM conductance of the NO radical adsorbed on the Au(111) surface. NO is an interesting test case, in the past only qualitatively considered as a prototype of radical-surface Kondo interactions (27, 28), whereas recently it has been used instead to quench the spin state of larger molecular radicals such as porphyrins (29).

Starting with DFT calculations of an idealized Au(111)/NO/STM tip geometry as shown in Fig. 1, we determined the adsorption geometry and the persistence of a nonzero spin state carried by the  orbitals of NO. A two-orbital Anderson model describing their hybridization with the gold surface Fermi sea was constructed and its parameters were adjusted to quantitatively reproduce the DFT results. The NRG solution of the Anderson model (NRG Results) determined which of the two

orbitals of NO. A two-orbital Anderson model describing their hybridization with the gold surface Fermi sea was constructed and its parameters were adjusted to quantitatively reproduce the DFT results. The NRG solution of the Anderson model (NRG Results) determined which of the two  orbitals, namely the one with odd symmetry, is eventually screened at the Kondo fixed point. A spectral function peak and a zero bias conductance anomaly were predicted with a Kondo temperature of about 15 K [half width at half maximum (HWHM) of 5 meV]. [Adopting Wilson’s definition, the Kondo temperature

orbitals, namely the one with odd symmetry, is eventually screened at the Kondo fixed point. A spectral function peak and a zero bias conductance anomaly were predicted with a Kondo temperature of about 15 K [half width at half maximum (HWHM) of 5 meV]. [Adopting Wilson’s definition, the Kondo temperature  is inferred from

is inferred from  (30), where the HWHM is extracted from the linewidth

(30), where the HWHM is extracted from the linewidth  obtained from a Frota lineshape fit (31).]

obtained from a Frota lineshape fit (31).]

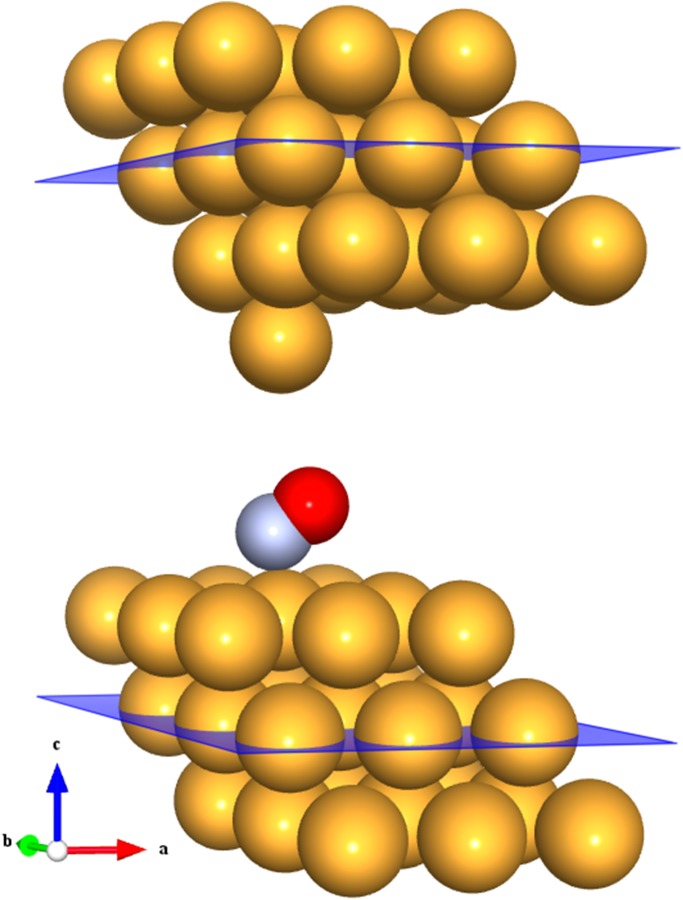

Fig. 1.

Model STM geometry for NO/Au(111). The scattering region shown contains one NO molecule and 28 Au atoms; it satisfies periodic boundary conditions in the transverse direction and is bounded by two planes in the c direction, where the potential is smoothly matched to the potential of bulk gold. NO is shown in the optimal on-top adsorption geometry, where the molecule is bent by about 60°. Figure produced using VESTA (46).

To check these predictions we carried out STM/scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) experiments (Experimental STM/STS Results) for NO/Au(111). A clear Kondo anomaly was found with an experimental Kondo temperature of about 43 K (HWHM = 16 meV). The observed conductance lineshape near zero bias, a sharp dip, is also quite close but exactly complementary to the calculated Kondo spectral peak. The broad agreement with experiment and especially the discrepancies represent an important critical validation, pointing out physical variables to be included in future calculations.

First-Principles Calculations and Modeling

The initial step is a DFT calculation (Materials and Methods and SI Text) of NO adsorbed on an unreconstructed Au(111) surface, adopted here as an approximation to the face-centered cubic (fcc) domains of the “herringbone” reconstructed Au(111) surface (32). Our calculations (Table S1) show that the only stable NO adsorption geometry is on top, with N pointing down toward a Au surface atom and, remarkably, a tilt angle of nearly 60° as illustrated in Fig. 1. NO also binds (with lower binding energy) at Au(111) bridge and hollow sites. However, in the low coverage limit these adsorption states are stable only when NO is constrained to be upright, for otherwise there is no barrier against migration to the optimal tilted on-top adsorption state. The calculated on-top adsorption energy 320 meV is weak and compares well with an estimated 400 meV from temperature-programmed desorption spectroscopy (33).

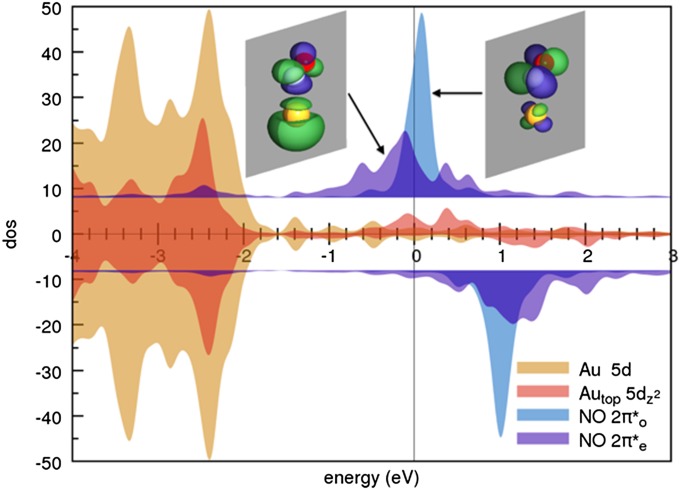

Consistent with that weak adsorption state, spin-polarized DFT shows the persistence of a magnetic moment close to one Bohr magneton, meaning that adsorbed NO retains its radical character as in vacuum. Both  molecular orbital resonances, their degeneracy lifted in the tilted on-top adsorption state, cross the gold Fermi level (Fig. 2). This is an important point—the DFT calculation partitions the single unpaired electron approximately equally between the two

molecular orbital resonances, their degeneracy lifted in the tilted on-top adsorption state, cross the gold Fermi level (Fig. 2). This is an important point—the DFT calculation partitions the single unpaired electron approximately equally between the two  orbitals, despite a significant splitting of the orbital energy levels due to the large tilt angle. Although the evidence of NO tilting in our STM images is not firmly established, its occurrence is convincingly stabilized by the resulting hybridization with the Au surface. Of the total impurity magnetization ∼55% originates from the more hybridized even

orbitals, despite a significant splitting of the orbital energy levels due to the large tilt angle. Although the evidence of NO tilting in our STM images is not firmly established, its occurrence is convincingly stabilized by the resulting hybridization with the Au surface. Of the total impurity magnetization ∼55% originates from the more hybridized even  orbital with lobes in the Autop-N-O plane (Fig. 2, Inset) and the remaining 45% from the less hybridized odd

orbital with lobes in the Autop-N-O plane (Fig. 2, Inset) and the remaining 45% from the less hybridized odd  orbital normal to that plane.

orbital normal to that plane.

Fig. 2.

Projected density of states for NO/Au(111). Spin-up states are plotted as positive values and spin-down states as negative. The densities of states of the NO  molecular orbitals (Insets) are estimated from weighted sums of the projections on N and O p orbitals. The Fermi energy is indicated by a vertical line. The

molecular orbitals (Insets) are estimated from weighted sums of the projections on N and O p orbitals. The Fermi energy is indicated by a vertical line. The  states of NO and the

states of NO and the  states of the top-site Au atom, Autop, are shifted and scaled for visibility.

states of the top-site Au atom, Autop, are shifted and scaled for visibility.

To calculate the hybridization of the molecular orbitals with the gold surface, we use the information contained in the calculated phase shifts of gold conduction electrons scattering off the adsorbed molecule (20, 21). The quantum mechanical scattering problem is solved numerically for the geometry in Fig. 1, using pwcond (34) (Materials and Methods), which provides spin-resolved phase shifts for the relevant symmetry channels. Here we focus on two symmetries, namely even (e) and odd (o) under reflection across the Autop-N-O plane, corresponding to the strongly and weakly hybridized NO  orbitals, respectively. Examples of resonances in the phase shifts are shown in Fig. S1. It should be noted for later discussion that the scattering problem involved only the Bloch states of bulk Au and not those of the surface.

orbitals, respectively. Examples of resonances in the phase shifts are shown in Fig. S1. It should be noted for later discussion that the scattering problem involved only the Bloch states of bulk Au and not those of the surface.

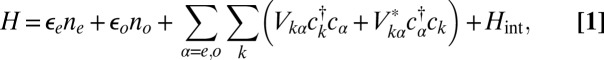

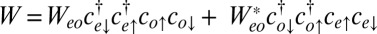

The next step of our theoretical protocol is to define an Anderson model Hamiltonian including channels of both symmetries,

|

where the subscript  stands for the

stands for the  state,

state,  describes hybridization with gold conduction states, and

describes hybridization with gold conduction states, and  contains all of the interactions in the

contains all of the interactions in the  manifold. When the molecule is brought down to the surface in an upright configuration at the on-top, fcc, or hexagonal close-packed (hcp) sites, the crystal field lowers the cylindrical symmetry of the isolated molecule to

manifold. When the molecule is brought down to the surface in an upright configuration at the on-top, fcc, or hexagonal close-packed (hcp) sites, the crystal field lowers the cylindrical symmetry of the isolated molecule to  . Further tilting of the molecule at the on-top site breaks

. Further tilting of the molecule at the on-top site breaks  symmetry and lifts the

symmetry and lifts the  degeneracy. The splitting of the

degeneracy. The splitting of the  and

and  levels (Fig. S2) and their unequal hybridization with gold conduction states, at first sight an irrelevant detail, is actually crucial to the Kondo physics, as we discuss below.

levels (Fig. S2) and their unequal hybridization with gold conduction states, at first sight an irrelevant detail, is actually crucial to the Kondo physics, as we discuss below.

The molecular orbitals hybridize with both surface and bulk states. Surface state hybridization affects the electronic structure of adsorption but only weakly. This is borne out in our slab calculations, where the adsorption energy converges already for 5 layers, whereas the energies of the surface states of the top and bottom of the slab—strongly split by their mutual interaction—do not converge until ∼23 layers (35). If surface state hybridization had a significant effect on the electronic structure, one would expect the adsorption energy to converge more slowly than it does. Surface states decay exponentially inside the bulk, and therefore their contribution to the hybridization and phase shifts, and hence to the conductance anomalies, is invisible in our scattering calculations, which involve only bulk scattering channels. We checked that the ab initio estimates of the molecular orbital hybridization linewidths  are well converged with respect to the number of layers of the slab.

are well converged with respect to the number of layers of the slab.

The interaction Hamiltonian is now written in terms of the  states as

states as

where the U terms are intrachannel and interchannel Hubbard interactions, the JH term is their Coulomb ferromagnetic (Hund’s rule) exchange interaction, and  is a small but nonzero pair hopping term. To fix the model parameters from the first-principles DFT input, we require the scattering phase shifts of the model Hamiltonian at the Hartree–Fock (mean-field) level to reproduce the phase shifts of the ab initio scattering calculation for the full system. The physical picture behind this type of matching is the local moment regime of the Anderson impurity model; because spin-polarized DFT and Hartree–Fock provide comparable mean-field descriptions of the local moment regime, we can reliably infer the model parameters by requiring them to give the same phase shifts. With four total phase shifts from the two channels and two spin polarizations, these conditions determine the four model parameters

is a small but nonzero pair hopping term. To fix the model parameters from the first-principles DFT input, we require the scattering phase shifts of the model Hamiltonian at the Hartree–Fock (mean-field) level to reproduce the phase shifts of the ab initio scattering calculation for the full system. The physical picture behind this type of matching is the local moment regime of the Anderson impurity model; because spin-polarized DFT and Hartree–Fock provide comparable mean-field descriptions of the local moment regime, we can reliably infer the model parameters by requiring them to give the same phase shifts. With four total phase shifts from the two channels and two spin polarizations, these conditions determine the four model parameters  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . To fix the remaining parameters

. To fix the remaining parameters  ,

,  , and

, and  , we make use of relationships between the interaction parameters that are exact for the isolated molecule (SI Text) and should still apply to the adsorbed molecule owing to its gentle physisorption. The resulting parameters (Table S2) provide all of the ingredients we need for a many body calculation of the spectral function and Kondo conductance anomaly.

, we make use of relationships between the interaction parameters that are exact for the isolated molecule (SI Text) and should still apply to the adsorbed molecule owing to its gentle physisorption. The resulting parameters (Table S2) provide all of the ingredients we need for a many body calculation of the spectral function and Kondo conductance anomaly.

NRG Results

The two-orbital Anderson model, Eq. 1, is solved by NRG (30, 36, 37); details are given in Materials and Methods. For tilted NO adsorbed at the on-top site, the solution indicates a competition between even and odd  orbitals. The

orbitals. The  is much more hybridized with the Au surface, whereas the

is much more hybridized with the Au surface, whereas the  has a lower bare energy, and it is thus unclear at the outset which of the two will host the Kondo resonance. We find, somewhat surprisingly, that at the fixed point the least hybridized, odd orbital is the winner, its spectral function displaying the Kondo resonance shown in Fig. 3E. By occupying the

has a lower bare energy, and it is thus unclear at the outset which of the two will host the Kondo resonance. We find, somewhat surprisingly, that at the fixed point the least hybridized, odd orbital is the winner, its spectral function displaying the Kondo resonance shown in Fig. 3E. By occupying the  more substantially than the

more substantially than the  , NRG inverts the mean-field orbital occupations initially obtained in DFT. At

, NRG inverts the mean-field orbital occupations initially obtained in DFT. At  , the NRG orbital occupations are

, the NRG orbital occupations are  and

and  , whereas the DFT occupations were

, whereas the DFT occupations were  and

and  . This exemplifies a situation of more general interest, showing that quantum fluctuations may cause one channel, even one predominant in mean field, to give way to another.

. This exemplifies a situation of more general interest, showing that quantum fluctuations may cause one channel, even one predominant in mean field, to give way to another.

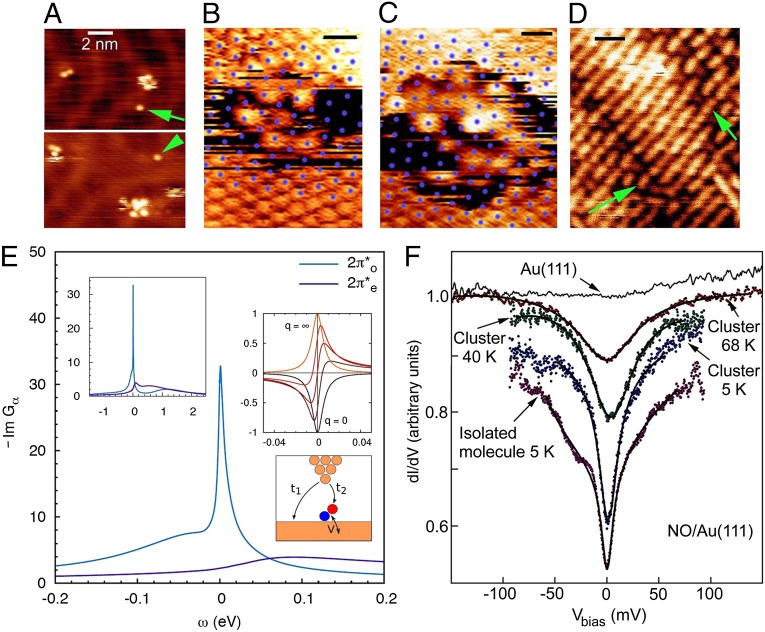

Fig. 3.

STM/STS images and spectra, all obtained with clean Au tips except for B and C. (A) Isolated NO molecules (arrows) and small NO clusters on Au(111) at 5 K. (B and C) Two small NO clusters formed from a few molecules (in the center) and substrate Au atoms (at the edges) imaged with a molecule on the STM tip. The Au lattice is marked by blue dots. Most of the molecules are on top. (Scale bar, 0.5 nm.) (D) Filled-state STM image  of an ordered single NO layer obtained after annealing at 70 K. The layer is made up of rows of units with a dumbbell shape that is consistent with the shape of the filled

of an ordered single NO layer obtained after annealing at 70 K. The layer is made up of rows of units with a dumbbell shape that is consistent with the shape of the filled  orbital. The arrows point to two of these units. (E) NRG spectral functions for the

orbital. The arrows point to two of these units. (E) NRG spectral functions for the  orbitals of NO at the on-top adsorption site calculated at 5 K with ab initio parameters from Table S2. Insets: spectral function (Left), Fano lineshapes (Upper Right), and interfering tunneling paths t1 and t2 (Lower Right). (F) Tunneling spectra of isolated molecules and small clusters at 5 K and clusters at 40 K and 68 K showing the Kondo dip. The spectra are shifted vertically for clarity. The solid lines are fits with the Frota function (31).

orbitals of NO at the on-top adsorption site calculated at 5 K with ab initio parameters from Table S2. Insets: spectral function (Left), Fano lineshapes (Upper Right), and interfering tunneling paths t1 and t2 (Lower Right). (F) Tunneling spectra of isolated molecules and small clusters at 5 K and clusters at 40 K and 68 K showing the Kondo dip. The spectra are shifted vertically for clarity. The solid lines are fits with the Frota function (31).

As a general note of caution we stress that our Anderson model is in a regime where the parameter dependence of the Kondo temperature, lineshape, and orbital population balance is rather critical. Kondo temperatures are particularly difficult to predict, given their exponential dependence on parameters. At the same time, the accuracy of the DFT electronic structure and phase shifts near  , which determine those parameters, is limited by inaccuracies and approximations, including in particular self-interaction errors. The Kondo temperature increases by a factor of 3 if the hybridization is increased by 20% or the orbital energy splitting

, which determine those parameters, is limited by inaccuracies and approximations, including in particular self-interaction errors. The Kondo temperature increases by a factor of 3 if the hybridization is increased by 20% or the orbital energy splitting  is decreased by only 50 meV. Further decreasing

is decreased by only 50 meV. Further decreasing  leads to a rather abrupt transition—via charge transfer from

leads to a rather abrupt transition—via charge transfer from  to

to  —to a state with a broad resonant level at

—to a state with a broad resonant level at  rather than a Kondo resonance. We stick here to the results predicted by our straightforward protocol, without adjustments or data fitting.

rather than a Kondo resonance. We stick here to the results predicted by our straightforward protocol, without adjustments or data fitting.

Experimental STM/STS Results

To verify the theoretical predictions just presented, we carried out STM measurements of NO adsorbed on Au(111). Submonolayer NO was dosed on a reconstructed Au(111) surface at 30 K, and the sample was then cooled to 5 K. STM images acquired with tunneling currents below 10−11 A show that the molecules adsorb preferentially at the fcc elbows of the gold herringbone surface reconstruction as isolated units or small disordered clusters at low coverage—below about 0.05 monolayers—and form large disordered clusters at higher coverage. The images of small clusters in Fig. 3 B and C indicate that the largest proportion of molecules adsorb on top, in agreement with the theoretical prediction. The average nearest-neighbor NO–NO distance in the clusters is about 0.5 nm. After annealing at 70 K, the molecules form ordered islands with a variety of metastable lattices with unit vectors between 0.35 nm and 0.60 nm. The angle between the unit vectors of the molecular lattices and those of the gold surface is between 0° and 30°. The structures either are incommensurate with the substrate or have a large unit cell with several inequivalent molecules, suggesting that the NO–NO interaction prevails over the NO–Au interaction. The NO lattice shown in Fig. 3D is formed by units that have a dumbbell appearance in the filled-state STM images. This shape is consistent with the charge distribution of the  orbital of the tilted molecule (Fig. 2) and supports the results of the NRG calculations that predict this state is preferentially filled.

orbital of the tilted molecule (Fig. 2) and supports the results of the NRG calculations that predict this state is preferentially filled.

STM spectra measured on isolated NO molecules, small disordered clusters, large disordered clusters, and ordered NO lattices all display similar dip-shaped conductance anomalies centered at the Fermi level, as shown in Fig. 3F. For isolated molecules, whose mobility at 5 K was too high to acquire images with enough resolution to detect the predicted on-top adsorption state and tilt angle, the HWHM of the dip is about 12 ± 4 meV at 5 K with an amplitude that is ∼25% of the background conductance. For NO clusters and lattices, the dip HWHM is 16 ± 4 meV at 5 K and depends on the position of the molecule. In addition to the zero bias dip, shoulders at ±30 meV are visible in the spectra taken over the isolated molecule but not over clusters (Fig. 3F). We have not been able to determine whether these inelastic features are of vibrational or electronic origin, but the symmetric displacement of the shoulders with respect to zero bias, as well as their disappearance in clusters, is suggestive of a vibrational origin. By DFT calculations we find vibrational eigenmodes with frequencies of 25 meV and 42 meV in the correct range. Spin transitions and anisotropy are not expected for a spin 1/2. Hypothetically, electronic states might offer an alternative explanation, the lower Hubbard band of the  state, visible just below Fermi in the NRG spectra (Fig. 3E), corresponding to the left shoulder, and the empty

state, visible just below Fermi in the NRG spectra (Fig. 3E), corresponding to the left shoulder, and the empty  state forming a resonance above Fermi, corresponding to the right shoulder. Altogether, an electronic explanation seems less likely.

state forming a resonance above Fermi, corresponding to the right shoulder. Altogether, an electronic explanation seems less likely.

No other sharp structures were observed between −0.8 eV and 0.8 eV from the Fermi level as shown in Fig. S3 and described in SI Text. In particular, the large step at −0.45 eV corresponding to the bottom of the clean Au(111) surface state band is absent in the spectra measured over molecules, indicating that free surface state electrons are pushed out by the NO molecule, to become detectable again in spectra 1–2 nm away. Although surface states are repelled, nevertheless their tails are expected to extend up to and hybridize with the NO radical.

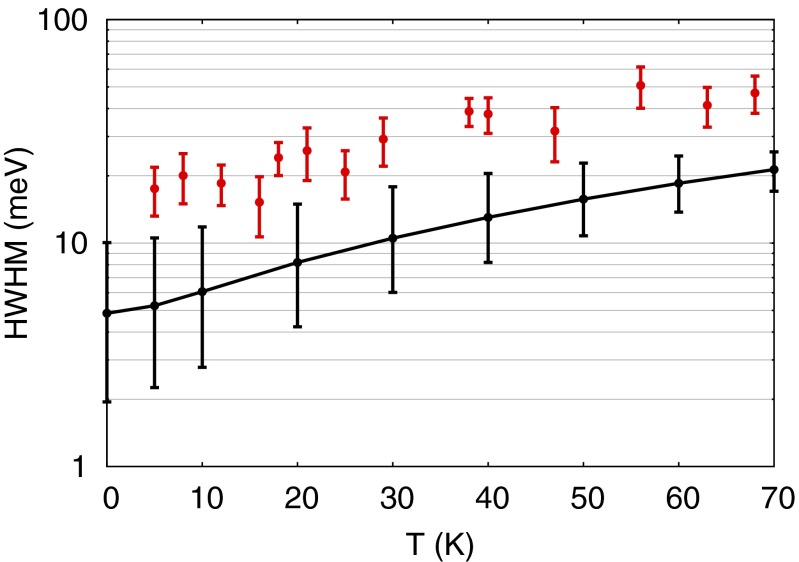

To further confirm the Kondo nature of the observed zero bias STM anomaly, the temperature dependence of the half width at half maximum of the dip was measured and is shown in Fig. 4. For each temperature, the lineshape was fitted with an asymmetric version (38) of the Frota function (31) with asymmetry parameter  . By 70 K, the HWHM has grown to 40–50 meV and the amplitude has decreased from ∼25% to ∼10% of the background. Due to the high mobility of the isolate molecules at high temperature and the ensuing difficulty of acquiring spectra for them, all data presented for

. By 70 K, the HWHM has grown to 40–50 meV and the amplitude has decreased from ∼25% to ∼10% of the background. Due to the high mobility of the isolate molecules at high temperature and the ensuing difficulty of acquiring spectra for them, all data presented for  were taken on NO islands. The effect of the temperature-induced broadening and attenuation of the dip is intrinsic because it is about a factor of 5 larger than the effect of the change of the experimental resolution of STS at high temperature related to the broadening of the Fermi distribution of the tip, corresponding to a HWHM of about 10 meV at 68 K. The large intrinsic broadening rules out inelastic tunneling (vibrational or electronic excitations) as the main origin of the dip. The Kondo temperature ∼43 K, extracted from the low-temperature limit of the Frota linewidth parameter

were taken on NO islands. The effect of the temperature-induced broadening and attenuation of the dip is intrinsic because it is about a factor of 5 larger than the effect of the change of the experimental resolution of STS at high temperature related to the broadening of the Fermi distribution of the tip, corresponding to a HWHM of about 10 meV at 68 K. The large intrinsic broadening rules out inelastic tunneling (vibrational or electronic excitations) as the main origin of the dip. The Kondo temperature ∼43 K, extracted from the low-temperature limit of the Frota linewidth parameter  , is about a factor of 3 larger than our unbiased theoretical prediction. This level of discrepancy is not surprising in view of the exponential sensitivity of the Kondo temperature to the impurity parameters and of the self-interaction errors generally affecting the first-principles DFT calculations.

, is about a factor of 3 larger than our unbiased theoretical prediction. This level of discrepancy is not surprising in view of the exponential sensitivity of the Kondo temperature to the impurity parameters and of the self-interaction errors generally affecting the first-principles DFT calculations.

Fig. 4.

Temperature dependence of the HWHM of the Kondo resonance from experiment (red) and NRG calculations (black) based on the ab initio parameters for the on-top adsorption geometry (Table S2). Experimental error bars indicate the SD calculated from a collection of spectra on different NO molecules. Spectra were measured on at least 10 different molecules at each temperature. The error bars on the theoretical curve represent the uncertainty corresponding to a ±20% uncertainty in the hybridization linewidth; uncertainty from other parameters is not depicted. Model parameter SDs are reported in Table S2.

Actually, a theoretical underestimate of the Kondo temperature is not unexpected, because the hybridization with gold surface states, as was mentioned above, is not completely accounted for in our calculations. Despite these deficiencies, the overall, unbiased theoretical results are gratifyingly reproduced, and so is the evolution of the zero bias anomaly with temperature, as shown in Fig. 4. The experimental offset of the center of the dip from the Fermi energy, less than 2 meV, is much less than the width, indicating that the parent level of the Kondo resonance is indeed nondegenerate. That provides an indirect and yet strong confirmation that the NO molecule is tilted, for if the  levels were degenerate, the Kondo peak would be shifted above the Fermi energy to satisfy the Friedel sum rule (39). The data do not clearly establish whether the symmetry of the Kondo orbital is odd as predicted, and that remains to be verified, e.g., by photoemission spectroscopy.

levels were degenerate, the Kondo peak would be shifted above the Fermi energy to satisfy the Friedel sum rule (39). The data do not clearly establish whether the symmetry of the Kondo orbital is odd as predicted, and that remains to be verified, e.g., by photoemission spectroscopy.

Finally, the observed Fano conductance lineshape (Fig. 3E, Inset), a  dip rather than

dip rather than  as predicted by the impurity spectral function, indicates that direct tunneling into the molecular

as predicted by the impurity spectral function, indicates that direct tunneling into the molecular  states (t2 in Fig. 3E, Inset) is dominated by another tunneling channel (t1). As STS indicates, the NO molecule is fully immersed in the Au(111) surface states, whose wave functions extend far out into the vacuum, reaching out to the STM tip. Because surface states do not represent a bulk screening channel, they are not included in our scattering calculations. Because the surface states are nonetheless involved and provide a free electron reservoir for Kondo screening, their local density of states near the molecule will show a dip at the Fermi energy, complementary to the calculated bare NO spectral function peak. As observed in the Kondo STM conductance anomalies of many other adsorbed magnetic atoms, and as generally discussed by Ujsaghy et al. (40),

states (t2 in Fig. 3E, Inset) is dominated by another tunneling channel (t1). As STS indicates, the NO molecule is fully immersed in the Au(111) surface states, whose wave functions extend far out into the vacuum, reaching out to the STM tip. Because surface states do not represent a bulk screening channel, they are not included in our scattering calculations. Because the surface states are nonetheless involved and provide a free electron reservoir for Kondo screening, their local density of states near the molecule will show a dip at the Fermi energy, complementary to the calculated bare NO spectral function peak. As observed in the Kondo STM conductance anomalies of many other adsorbed magnetic atoms, and as generally discussed by Ujsaghy et al. (40),  spectra are strongly modified, in our case very plausibly dominated, by direct tunneling into nearby metal surface states, specularly reversing the intrinsic Kondo anomaly.

spectra are strongly modified, in our case very plausibly dominated, by direct tunneling into nearby metal surface states, specularly reversing the intrinsic Kondo anomaly.

Conclusions and Outlook

We have described how the Kondo parameters and resulting zero bias STM conductance anomaly of an adsorbed molecular radical can be predicted from first principles, with features that compare reasonably well with those of a subsequent experiment. To do so, we used NO as the simplest spin 1/2 molecular radical capable of forming a Kondo screening cloud when adsorbed on a gold surface. The discrepancies between the calculated Kondo temperature and lineshape, which we did not try to amend in any way, and the measured ones are quite instructive, highlighting in particular the need to fully incorporate the metal surface states in future calculations. The delicate renormalization group flow toward the least hybridized, odd symmetry  state also appears as an instructive many body effect and remains a prediction to be verified. The magnetic field splitting of the Kondo anomaly, presently academic in view of the large value of TK, could easily be calculated if need be.

state also appears as an instructive many body effect and remains a prediction to be verified. The magnetic field splitting of the Kondo anomaly, presently academic in view of the large value of TK, could easily be calculated if need be.

The protocol implemented here for NO/Au(111) in a specific STM geometry is of more general applicability and can be applied to different molecular radicals and different STM and break junction geometries, where the influence of structural or mechanical deformations could be explored. As an overall result, the DFT+NRG approach demonstrates enough predictive power to be useful in the a priori evaluation of the conductance characteristics of molecular radical nanocontacts, thus providing a theoretical asset of considerable technological relevance.

Materials and Methods

Density functional theory calculations in the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew et al. (41) were performed with Quantum Espresso (42), a plane wave pseudopotential electronic structure package. The NO/Au(111) adsorption geometry was determined using the slab method in a 3 × 3 surface supercell with a vacuum layer of 16.9 Å. Scattering calculations were carried out with pwcond (34) in a 3 × 3 supercell with a vacuum layer of 8.4 Å, in correspondence with the experimental tip height of ∼10 Å. Brillouin zone integrations were performed on a 6 × 6 × 2 k-point mesh with a smearing width of 0.002–0.010 Rydberg. Plane wave cutoffs were 30 Rydberg for the wave function and 360 Rydberg for the charge density. As detailed in SI Text, Hubbard interactions were applied to the d states of Au (U = 1.5 eV) and the p states of N and O (U = 1.0 eV).

Numerical renormalization group calculations were carried out with NRG Ljubljana (41), using the z-averaging technique (30), the full density matrix approach (43), and the self-energy trick (44). The logarithmic discretization parameter was chosen to be  , and a maximum of 2,000 states (not counting multiplicities), corresponding to roughly 5,000 total states, were kept at each iteration. Spectral functions were obtained by log-Gaussian broadening (45) and at finite temperature with a kernel that interpolates between a log-Gaussian at high energy and regular Gaussian at low energy (43).

, and a maximum of 2,000 states (not counting multiplicities), corresponding to roughly 5,000 total states, were kept at each iteration. Spectral functions were obtained by log-Gaussian broadening (45) and at finite temperature with a kernel that interpolates between a log-Gaussian at high energy and regular Gaussian at low energy (43).

The dI/dV spectra were measured with a clean Au tip by the lock-in technique, applying a 3-meV modulation to the bias voltage and using a maximum current of  A to avoid tip-induced modification of the adsorption geometry. NO molecules were easily displaced at higher tunneling currents at 5 K and were mobile at temperatures above 20–30 K. The gold lattice and molecules could be resolved simultaneously only once (Fig. 3 B and C), when an unknown molecule adsorbed on the tip. The horizontal stripes in Fig. 3 B and C are caused by temporary detachments or shifts of this molecule. The broadening of the tunneling spectra caused by the finite modulation voltage is taken into account in the fit of the measured spectra by calculating the convolution of the Frota function with

A to avoid tip-induced modification of the adsorption geometry. NO molecules were easily displaced at higher tunneling currents at 5 K and were mobile at temperatures above 20–30 K. The gold lattice and molecules could be resolved simultaneously only once (Fig. 3 B and C), when an unknown molecule adsorbed on the tip. The horizontal stripes in Fig. 3 B and C are caused by temporary detachments or shifts of this molecule. The broadening of the tunneling spectra caused by the finite modulation voltage is taken into account in the fit of the measured spectra by calculating the convolution of the Frota function with  , where

, where  is the peak- to-peak value of the modulation voltage and V is the bias. This function represents the response of the STS spectroscopy with a sinusoidal modulation of the bias and a lock-in amplifier to a delta function-like density of states. The effect of the thermal broadening of the Fermi distribution in the tip at high temperature was taken into account by computing the convolution of the Frota function with the derivative of the Fermi distribution.

is the peak- to-peak value of the modulation voltage and V is the bias. This function represents the response of the STS spectroscopy with a sinusoidal modulation of the bias and a lock-in amplifier to a delta function-like density of states. The effect of the thermal broadening of the Fermi distribution in the tip at high temperature was taken into account by computing the convolution of the Frota function with the derivative of the Fermi distribution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the use of the NRG Ljubljana code and the high-performance computing resources of CINECA. Work was partly sponsored by Contracts Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale/Cofinanziamento 2010LLKJBX 004 and 2010LLKJBX 007, Sinergia CRSII2136287/1, and advances of European Research Council Advanced Grant 320796–MODPHYSFRICT.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1322239111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Aviram A, Ratner MA. Molecular rectifiers. Chem Phys Lett. 1974;29(2):277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed MA, et al. Conductance of a molecular junction. Science. 1997;278:252–254. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joachim C, Gimzewski JK, Aviram A. Electronics using hybrid-molecular and mono-molecular devices. Nature. 2000;408(6812):541–548. doi: 10.1038/35046000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewson A. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madhavan V, Chen W, Jamneala T, Crommie MF, Wingreen NS. Tunneling into a single magnetic atom: Spectroscopic evidence of the kondo resonance. Science. 1998;280(5363):567–569. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Schneider W-D, Berndt R, Delley B. Kondo scattering observed at a single magnetic impurity. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;80(13):2893–2896. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks JJ, et al. Mechanical control of spin states in spin-1 molecules and the underscreened Kondo effect. Science. 2010;328(5984):1370–1373. doi: 10.1126/science.1186874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott GD, Natelson D. Kondo resonances in molecular devices. ACS Nano. 2010;4(7):3560–3579. doi: 10.1021/nn100793s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahl P, et al. Kondo effect of molecular complexes at surfaces: Ligand control of the local spin coupling. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95(16):166601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.166601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao A, et al. Controlling the Kondo effect of an adsorbed magnetic ion through its chemical bonding. Science. 2005;309(5740):1542–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.1113449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iancu V, Deshpande A, Hla S-W. Manipulating Kondo temperature via single molecule switching. Nano Lett. 2006;6(4):820–823. doi: 10.1021/nl0601886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Y, Zhang YN, Cao JX, Wu RQ, Ho W. Real-space imaging of Kondo screening in a two-dimensional O2 lattice. Science. 2011;333(6040):324–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1205785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugarza A, et al. Spin coupling and relaxation inside molecule-metal contacts. Nat Commun. 2011;2:490. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müllegger S, Rashidi M, Fattinger M, Koch R. Interactions and self-assembly of stable hydrocarbon radicals on a metal support. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2012;116(42):22587–22594. doi: 10.1021/jp3068409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müllegger S, Rashidi M, Fattinger M, Koch R. Surface-supported hydrocarbon π radicals show Kondo behavior. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2013;117(11):5718–5721. doi: 10.1021/jp310316b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y-H, et al. Temperature and magnetic field dependence of a Kondo system in the weak coupling regime. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2110. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J, et al. Coulomb blockade and the Kondo effect in single-atom transistors. Nature. 2002;417(6890):722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature00791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parks JJ, et al. Tuning the Kondo effect with a mechanically controllable break junction. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99(2):026601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.026601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osorio EA, et al. Electronic excitations of a single molecule contacted in a three-terminal configuration. Nano Lett. 2007;7(11):3336–3342. doi: 10.1021/nl0715802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucignano P, Mazzarello R, Smogunov A, Fabrizio M, Tosatti E. Kondo conductance in an atomic nanocontact from first principles. Nat Mater. 2009;8(7):563–567. doi: 10.1038/nmat2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baruselli PP, Smogunov A, Fabrizio M, Tosatti E. Kondo effect of magnetic impurities in nanotubes. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108(20):206807. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.206807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baruselli PP, Smogunov A, Fabrizio M, Tosatti E. Kondo effect of magnetic impurities on nanotubes. Physica E. 2012;44(6):1040–1044. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.206807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costi TA, et al. Kondo decoherence: Finding the right spin model for iron impurities in gold and silver. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102(5):056802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.056802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob D, Haule K, Kotliar G. Kondo effect and conductance of nanocontacts with magnetic impurities. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103(1):016803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.016803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias da Silva LGGV, Tiago ML, Ulloa SE, Reboredo FA, Dagotto E. Many-body electronic structure and Kondo properties of cobalt-porphyrin molecules. Phys Rev B. 2009;80:155443. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surer B, et al. Multiorbital Kondo physics of Co in Cu hosts. Phys Rev B. 2012;85:085114. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimori A. Does a localized spin of adsorbed NO survive on Cu(111)? Surf Sci. 1995;342:L1101–L1103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez Jigato M, King DA, Yoshimori A. The chemisorption of spin polarized NO on Ag{111} Chem Phys Lett. 1999;300:639–644. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wäckerlin C, et al. Controlling spins in adsorbed molecules by a chemical switch. Nat Commun. 2010;1:61. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Žitko R, Pruschke T. Energy resolution and discretization artifacts in the numeric renormalization group. Phys Rev B. 2009;79:085106. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frota HO. Shape of the Kondo resonance. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1992;45(3):1096–1099. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.45.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barth JV, Brune H, Ertl G, Behm RJ. Scanning tunneling microscopy observations on the reconstructed Au(111) surface: Atomic structure, long-range superstructure, rotational domains, and surface defects. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1990;42(15):9307–9318. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.42.9307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClure SM, Kim TS, Stiehl JD, Tanaka PL, Mullins CB. Adsorption and reaction of nitric oxide with atomic oxygen covered Au(111) J Phys Chem B. 2004;108(46):17952. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smogunov A, Dal Corso A, Tosatti E. Ballistic conductance of magnetic Co and Ni nanowires with ultrasoft pseudopotentials. Phys Rev B. 2004;70:045417. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forster F, Benounan A, Reinert F, Grigoryan VG, Springborg M. Surf Sci. 2007;601:5595–5604. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Žitko R (2013) NRG Ljubljana. Available at http://nrgljubljana.ijs.si. Accessed March 1, 2013.

- 37.Bulla R, Costi TA, Pruschke T. Numerical renormalization group method for quantum impurity systems. Rev Mod Phys. 2008;80:395–450. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prüser H, Wenderoth M, Weismann A, Ulbrich RG. Mapping itinerant electrons around Kondo impurities. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108(16):166604. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.166604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi M-S, López R, Aguado R. SU(4) Kondo effect in carbon nanotubes. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95(6):067204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.067204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Újsághy O, Kroha J, Szunyogh L, Zawadowski A. Theory of the fano resonance in the STM tunneling density of states due to a single kondo impurity. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;85(12):2557–2560. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giannozzi P, et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J Phys Condens Matter. 2009;21(39):395502. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weichselbaum A, von Delft J. Sum-rule conserving spectral functions from the numerical renormalization group. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99(7):076402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.076402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bulla R, Hewson AC, Pruschke T. Numerical renormalization group calculations for the self-energy of the impurity Anderson model. J Phys Condens Matter. 1998;10:8365–8380. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bulla R, Costi TA, Vollhardt D. Finite-temperature numerical renormalization group study of the Mott transition. Phys Rev B. 2001;64:045103. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Momma K, Izumi F. 2013. VESTA visualization program. Available at http://jp-minerals.org/vesta. Accessed February 1, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.