Abstract

Studies investigating effectiveness of group psychotherapy intervention in depression in persons with HIV have showed varying results with differing effect sizes. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of group psychotherapy in depression in persons with HIV has been conducted to present the best available evidence in relation to its effect on depressive symptomatology. Electronic databases were searched to identify randomized controlled trials. Selected studies were quality assessed and data extracted by two reviewers. If feasible, it was planned to conduct a meta-analysis to obtain a pooled effect size of group psychotherapeutic interventions on depressive symptoms. Odds ratio for drop out from group was calculated. The studies were assessed for their quality using the Quality Rating Scale and other parameters for quality assessment set out by COCHRANE. The quality of reporting of the trials was compared against the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist for non-pharmacological studies (CONSORT-NPT). Four studies met the full inclusion criteria for systematic review. The trials included in the review examined group interventions based on the Cognitive behavioral therapy model against other therapeutic interventions or waiting list controls. In all four studies, group psychotherapy was an effective intervention for reducing depressive symptoms in persons with HIV in comparison to waiting list controls. The reported benefits from the group psychotherapy in comparison to active controls were less impressive. There were no statistically significant differences in drop outs at post treatments across group psychotherapy, wait list control, and other active interventions. The methodological quality of the studies varied. The quality of reporting of the studies was sub-optimal. The results of this systematic review support that group psychological interventions for depression in persons with HIV have a significant effect on depressive symptomatology. This review also indicates that group cognitive behavioral therapies are an acceptable psychological intervention for persons with HIV and comorbid depression.

Keywords: Depression, group psychotherapy, HIV

INTRODUCTION

Depression is highly prevalent in individuals with HIV.[1] Depression increases HIV-related morbidity and mortality including those from suicide.[2] Depression also delays initiation of anti-retroviral treatment,[3] affects adherence to treatment and reduces important self-care behaviors[4,5] in individuals with HIV.

Treatment for depression improves HIV-related outcomes.[6,7] Antidepressants though efficacious in depression associated with HIV, they are associated with high dropout rates and are expensive.[8,9] Drug interactions with anti-retroviral agents and sexual dysfunction after antidepressant use are additional concerns.[10,11]

Psychotherapeutic interventions have also been used to alleviate psychosocial, interpersonal difficulties, and distress associated with HIV. Several randomized controlled trial studies have investigated the efficacy of group therapy techniques to decrease psychological distress, decrease social isolation, and improve coping among HIV-infected people.[12,13,14,15,16,17] The number of psychotherapists is often limited in clinical practice with long waiting lists preventing timely delivery of psychotherapeutic interventions and implementation of guidelines. One possible solution would be to provide group-based rather than individual psychotherapy. Steuer et al. suggested that group therapy works effectively because it offers peer support, mitigates social isolation, encourages shared empathy, and provides a context for peer feedback and patients have the opportunity to help one. It may also be cost effective.[18] Group interventions are well suited to meet the needs of an HIV-positive individuals with depression as depression is often accompanied by social isolation, physical disability, and bereavement.[19]

Cognitive and behavioral psychotherapies as well as interpersonal therapy have the most empirical support in treating depression.[20,21,22] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) appears to have an enduring effect that reduces subsequent risk following treatment termination.[23]

A recent meta-analysis by Cuijipers et al.[24] found only small difference in effects (0.20) between individual interventions and group interventions in the treatment of depression in the short term and no such differences were apparent during the long-term follow-up. It is not clear whether such a difference is clinically relevant. It is estimated that the costs of group therapy are about half of the costs of individual therapy.[25] Because the costs of group treatments are considerably lower than the costs of individual therapy, it is not clear whether the small difference in effects is worth the costs. The dropout rate is significantly higher in individual therapy compared to groups. This may even increase the cost effectiveness of group therapies further.[24] Group therapies are at least as acceptable as individual therapies and that additional advantages conferred by groups possibly increase treatment adherence.[24]

Previous meta-analysis of psychological interventions in depression in persons with HIV by Seth Himelhoch et al.[26] confirms that psychological treatments are effective at post treatment with a mild to modest effect size. This meta-analysis of seven RCTs included studies with and without baseline depression. Therefore, from this meta-analysis, it is difficult to delineate the effect of group psychological interventions in those patients who are HIV positive and have elevated depressive symptoms. We are not aware of other meta-analysis or systematic reviews which have examined the effect of group psychotherapies in adults with HIV with depression. With advancement in delivery of group psychotherapies, it is of public health importance to summarize the effect of group psychotherapy in those with HIV and depression. Therefore, it was decided to conduct such a meta-analytic review.

AIMS OF THE STUDY

Aim of the study was to conduct a systematic review with a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of group psychotherapy in depression in individuals with HIV and present the best available evidence in relation to effectiveness of psychotherapies in depression in individuals with HIV.

In addition, the methodological quality and quality of reporting of the eligible clinical trials included in the meta-analyses will be evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification and selection of studies

Data sources

The search strategy was designed to access both published and unpublished materials until December 2010. Medline, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Cochrane central register of controlled trials were searched. Major bodies providing evidence and good practice guidelines like NICE, Society of Psychotherapy Research, and British association of psychotherapy were reviewed. Unpublished studies were searched through dissertation abstracts. Citations for additional trials from reference lists and indexing of key papers was checked to locate relevant articles that might have been missed. Previous two years of AIDS Patient Care and STDs, British Journal of Psychiatry, and the British Journal of Psychotherapy were manually searched. There was no limit on the age of the studies and no language restrictions were applied. Experts in the field were contacted for any ongoing and unpublished trials. The population search terms (both MeSH terms and text words) included “depression, dysthymia, adjustment disorder, affective disorder, subclinical depression, subthreshold depression, minor depression” and were combined with intervention terms such as “group therapy, cognitive therapy, behaviour therapy, psychotherapy.”

We defined the following inclusion criteria:

All randomized and cluster-randomized controlled trials from all settings

Studies with adults aged 16 years and above

Subjects with clinically relevant depressive symptoms as indicated by elevated depression scores on a standardized depression inventory

At least one form of formalized psychotherapeutic treatment in a group setting. A group was defined as having three or more members

The group psychotherapeutic intervention was not being administered in combination with any other psychotherapy, educational, or psychosocial interventions

There was no limit on the length of treatment or the number of group sessions

Physical or other comorbidity was allowed as long as the subjects fulfilled the criteria for depression. This was irrespective of whether the depressive symptoms were primary or secondary to the physical illness.

No language restriction or age limits were applied. When available during the database search, limits appropriate to age, controlled trials, clinical trials, and randomized controlled trials where applied.

Studies with patients suffering from psychiatric disorders other than depression, significant cognitive impairment including dementia, primary diagnosis of alcohol or drug dependence, and those experiencing psychotic symptoms were excluded. Reviews and studies that were purely qualitative in nature were not included. Trials where group psychotherapy was administered in combination with other therapies, pharmacotherapy, as a part of a multi-component intervention, as a stepped care management, or as a part of care management where the effect specific to group psychotherapy was unable to be estimated were excluded. Trials which did not have depression at baseline were excluded. Trials which were not randomized controlled trials were excluded.

Evidence was sought to confirm that the psychotherapeutic treatments were manualized and standardized. When described, the supervisory arrangements from each trial were recorded. The studies were assessed for their quality using the Quality Rating Scale (QRS),[27] and the parameters for quality assessment set out by COCHRANE.[28] The quality of reporting of the trials was compared against the CONSORT checklist for non-pharmacological studies (CONSORT-NPT).[29]

STATISTICAL METHODS

For the statistical analysis, data from individual studies were collected using a data extraction tool that was specifically developed for the purpose of this review. Changes in outcome measures at post-treatment and during follow-up were recorded. Summary statistics were based on intention to treat data and when missing on available case analysis. When the data were insufficient or unclear, the key author was contacted by email requesting to provide the missing information. Where studies used the same instruments, the mean differences on depression inventories across studies were compared using independent t tests with two-sided variance. If it was possible to conduct a meta-analysis, it was planned to pool the mean differences to provide combined effect size. If possible, it was planned to evaluate publication bias by funnel plot or Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure.

If sufficient number of studies were included, it was planned to carry out appropriate sensitivity and subgroup analysis to evaluate the effects of low-quality trials and to explore the effect of differences in terms of severity of depression, intervention groups were compared with waiting list control groups and then with active control groups. Odds ratios for loss to follow-up were calculated for experimental and all control conditions.

RESULTS

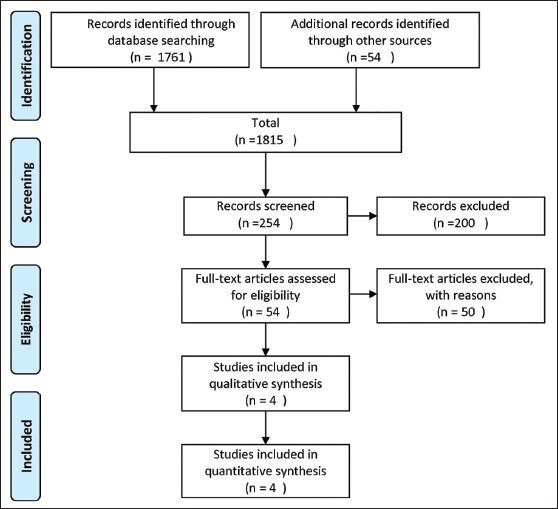

Electronic searches generated a total of 1 761 potentially eligible studies (651 from Embase, 129 from Medline in process, 541 from Embase, 279 from psychInfo, 78 from British Nursing Index and 83 from Controlled trials register) [Figure 1]. After initially screening 1 761 abstracts, 180 studies were obtained for full paper review. Of the 86 studies from cross-references that appeared potentially eligible, 54 full papers were obtained for further scrutiny. Therefore, in total, 254 full papers were evaluated against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of all, 73 randomized controlled trials of group psychotherapy in adults aged 16 years and above with depressive symptoms at pre-treatment were identified. Of these, 37 were in patients with depressive disorder as established using standardized diagnostic criteria. Twenty-five studies included patients with elevated depressive symptoms on a depressive inventory with no attempt to establish whether they were clinically depressed. There were ten randomized controlled trials of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals.[6,7,12,13,14,15,16,17,30,31] Of these, five studies[6,7,14,16,17] did not have depression at baseline. Zisook et al.'s study[32] was excluded as it compared the effectiveness of group therapy with fluoxetine against group therapy with placebo. Therefore, we were left with four studies that were eligible and included in the systematic review. All these studies reported depression as a continuous measure. However, diverse and multiple scales were used to measure depression and therefore we were unable to conduct meta-analyses.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart somewhere here

All trials were randomized controlled trials with parallel design. All were single center trials. Patients were randomized to therapeutic or control interventions. Control groups were either waiting list subjects or controls receiving any other form of active intervention like Social support group or HIV Info. Apart from one study from Hong Kong,[12] all other studies were carried out in the United States. All four studies had waiting list controls of which Chesney 2003 and Kelly 1993 had both active controls and waiting list controls. Most trials were small. Chesney 2003 was the largest with 54 patients randomized to intervention, 51 randomized to active control, and 44 randomized to waiting list control group. Cruses 2002 had 62 patients in the intervention arm and 38 in the control group. All other studies had less than 30 participants in each arm of the study.

Types of participants

All studies involved only men, with one study (Kelly 2003) involving women initially, but later involving only men due to refusal by women participants to be in a group with men. Kelly 2003 recruited patients through community announcements and referrals. Chesney 2003 recruited through advertisements in local gay bars, brochures, and HIV clinics. Cruses 2002 recruited through physician referrals and referrals from previous participants. Chan 2003 recruited from a pool of 62 patients attending Clinical AIDS service at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong. All studies excluded participants with significant cognitive impairment. All studies excluded patients with psychosis and psychotic depression. Other exclusion criteria were other mental illness, alcohol and substance problems, psychotropic medication or currently in therapy, and severe physical illness. In all studies, participants suffered from at least mild to moderate degree of depression as indicated by mean scores on depression inventories.

Types of intervention

All studies employed group psychotherapeutic interventions with practice principles derived from the cognitive behavioral school of psychotherapy. Two trials, Chesney 2003 and Kelly 1993 had more than one comparator. Chesney 2003 compared cognitive behavioral group therapy, HIV Info, and waiting List control. Kelly 1993 compared cognitive behavioral group therapy, Social support, and waiting List control. Chan 2004 and Cruess 2002 compared cognitive behavioral group therapy with waiting list. In all the trials, the experimental group therapy was delivered weekly. Two trials lasted 10 weeks (Cruess 2002, Chesney 2003). One trial lasted 8 weeks (Kelly 1993). One trial lasted 7 weeks (Chan 2004). Cruess 2002 and Chan 2004 had no post-treatment follow-up. Kelly 1993 followed up patients for 5 months. Chesney 2003 followed up patients for 12 months.

Types of outcome measures

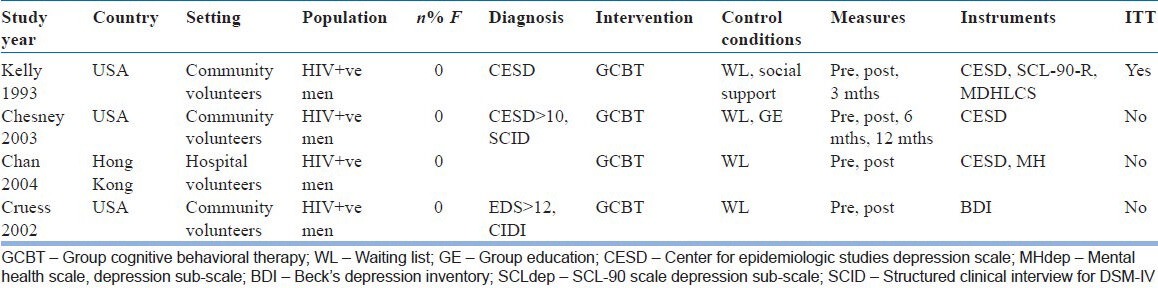

Trials used various diagnostic criteria for identification and classification of depressive symptoms. All primary outcome measures were changes in scores in well-established depression scales. Kelly 1993 is the only study with dichotomous outcome for depression. Kelly 1993, Chesney 2003, and Chan 2004 used Centre for Epidemiological studies-Depression scale (CES-D). Crues 2002 used Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI). As secondary outcome measures, Kelly 1993 used Global Severity Index, depression, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, and anxiety as part of SCL-90-R scale. As secondary outcome measures, Chesney 2003 used perceived stress (perceived stress scale), burnout, negative morale, positive morale (affect balance scale), and anxiety (state trait anxiety inventory). Cruess 2002 used Cognitive coping self efficacy, Dysfunctional attitude scale, and Interpersonal Support evaluation list. Chan 2004 used Medical outcomes study short form 36 (SF-36) to measure health-related quality of life. Regarding dropouts, in Chan 2004, of the 16 participants recruited (eight into each group), two from the Intervention group and one from the waiting list group dropped out. Completion and dropout rates are unclear in the study by Cruess 2002. In the study by Chesney 2003, 128 of 149 completed the intervention phase, 79 were retained at 6 months and 70 at 12 months with no significant differences in rates of retention between groups. In the study by Kelly 1993, 115 entered the study and 77 were assigned to intervention groups and 38 to waiting list. Forty-five from the intervention group completed the full intervention and post-intervention follow-up. The common reasons for dropouts in all four studies were relocation, illness, and time constraints. In the study by Kelly 1993, ten women who had initially enrolled dropped out as they wanted to be in a group with women only. Key characteristics of these are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies

QUALITY ASSESSMENT

Based on QRS assessments, the four studies included in the review achieved reasonable QRS scores of between 22 and, 30 with an overall mean score of 26.5 out of a maximum score of 46. The studies were rated independently by two authors (AJ and AK) with mean inter-rater reliability of kappa = 0.7.

The quality of reporting was suboptimal with all studied missing at least six of the items on CONSORT-NPT relating to methodological issues in the trials. The mean number of items reported on CONSORT-NpT was 16.25 (1-5 SD) of a total of 26 items.

The following parameters as recommended by Higgins and Green 2005 were applied to evaluate the quality of intervention:

Standardization and monitoring: All used structured and manualized psychotherapy. Treatment adherence was verified independently

Randomization and allocation of concealment: In all studies, there was randomization but no evidence of blinding of assessors

Characteristics of therapists: In the study by Cruess 2002, the intervention group was led by Advanced clinical health psychology pre-doctoral graduate training manual and had weekly face-to-face supervision by a board-certified psychiatrist and a licensed clinical psychologist. In the study by Chesney 2003, Coping Effectiveness Training and Hiv info groups were led by male and female co-leaders who were trained in Coping Effectiveness Training and Hiv info. They were supervised by the principal investigator and senior co-leader and the sessions were taped. In the study by Kelly 1993, the group leaders are mentioned as being experienced and of the same age and experience in both intervention and control groups. In the study by Chan 2005, the intervention group was led by a clinical psychologist specialized in treating HIV-infected patients and a clinical psychologist in training.

As there were only four eligible trials, it was not feasible to evaluate publication bias.

Effect on depression

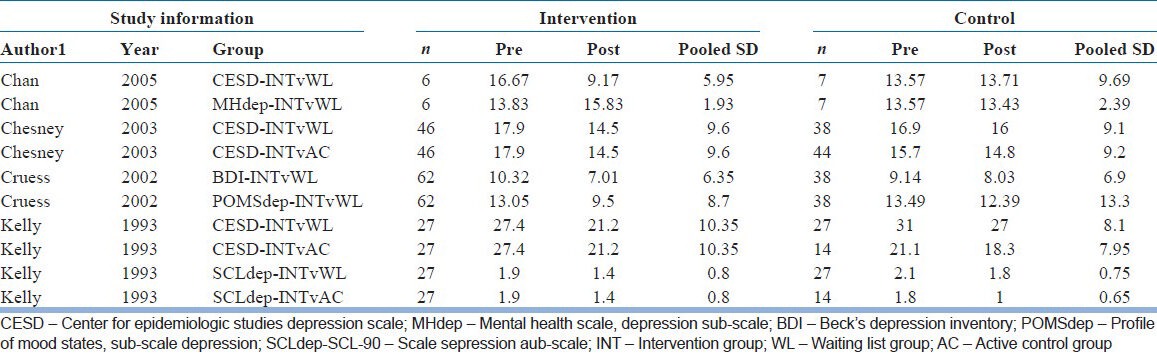

This systematic review provides an indication that group psychotherapies are effective in reducing depressive symptoms at post-treatment in comparison to waitlist. This was observed in all the four studies included in this review. Chesney 2003 compared group psychotherapy (coping effectiveness training) with active control Hiv-info for its effect on depression and found that group psychotherapy (coping effectiveness training) is more effective in reducing depressive symptoms at post treatment in comparison to active control Hiv-info. Kelly 1993 compared group psychotherapy with social support group and found no difference between the two interventions in reducing depressive symptoms. Cruess 2002 found that group psychotherapy (cognitive behavioral stress management) is more effective in reducing depressive symptoms at post treatment in comparison to active control social support. The benefit derived from group psychotherapies at post treatment may be maintained at follow up (Chesney 2003, Kelly 1993). The mean change on depressive inventories pre- and post-treatment for all comparison across four studies with a key is provided in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in degree of change on the depression inventory in three trials which used a common depression scale (CESD). The independent – sample t test was used to test the significance of the difference between pre and post score of intervention between group psychotherapy vs all controls. The mean difference between pre and post score of intervention was significantly different from that of the controls. The mean score of intervention group was 5.34 (SD 1.85) and controls was 1.69 (SD 1.67) with P value of 0.01.

Table 2.

Scores on depressive interventories for all comparisons across all studies included in the systematic review

Secondary outcomes

Cruess 2002 found group psychotherapy (cognitive behavioral stress management) to be effective in reducing dysfunctional attitudes and improving coping skills. Chan 2005 found improvements in anxiety, physical role, and emotional role as measured by the SF-36 scale post group psychotherapy. Kelly 1993 found reduction in hostility, somatisation, and illicit substance use in individuals who received group psychotherapy. Chesney 2003 found significantly decreasing perceived stress and burnout and increasing coping self efficacy in individuals receiving group psychotherapy.

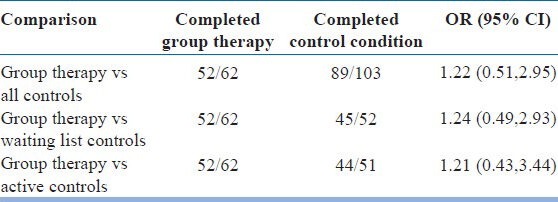

There were no statistically significant differences in drop outs at post treatments across group psychotherapy, wait list control, and other active interventions [Table 3].

Table 3.

Drop outs across different groups

DISCUSSION

The trials included in the review examined group interventions based on the CBT model with active therapeutic interventions or waiting list controls. The reported benefits from the group psychotherapy in comparison to active controls were less impressive. The review confirms that group psychotherapy is an effective intervention in reducing depressive symptoms in HIV-infected individuals in comparison to waiting list controls. There were indications from individual studies that secondary outcomes like Quality of life (Chan 2005), positive morale (Chesney 2003), anxiety, and reduced use of illicit substances (Kelly 1993) improved at post treatment.

A large-scale outcome-focused study with appropriate comparators like pharmacotherapy and individual psychotherapy is warranted to define the efficacy of group psychotherapy for HIV-infected individuals. This would also serve as a common benchmark of group efficacy to which researchers and clinicians can refer.[31] All the trials have used CBT model in group therapy, future trials examining group psychotherapies in different modalities in HIV-infected individuals are essential. All the trials have involved men; hence, we are unable to say whether the same results apply to women. Secondary outcome measures assessing quality of life, disability, feasibility, acceptance of and satisfaction with the therapy should be included. The study design should incorporate qualitative data collection regarding individual preference and attitudes toward treatment. Pragmatic trials of group therapy in diverse settings exploring therapy factors, therapist factors, and group factors are also necessary.

Limitations

The sample size in most studies is small. None of the trials evaluate the benefit of group psychotherapy against individual therapy. None of the trials included in the review evaluated the benefits of psycho-dynamic or interpersonal therapies in HIV-infected individuals. There were no trials comparing the benefits of psychotherapy in formal groups with guided self help or self-help groups.

None of the trials adequately reported how therapy or the control intervention was delivered or modified to suit the needs of HIV-infected individuals. None of the studies have carried out component analyses which would have helped delineate the active components in group therapy. Little is described about the characteristics, expertise, and effect of the therapists on the outcomes. None of the studies involved women participants. The relatively small size of the studies, the nature of populations, relatively high-attrition rate, and the heterogeneity of the interventions can limit the generalizability of the study and the ability to replicate the interventions in clinical practice. Various definitions and measures were used to diagnose depression and evaluate the severity of depressive symptoms. Only in one study Kelly 1993 reports “clinical response” or “remission” as dichotomous outcome. The rest merely report a change on depression scores. This reduces the relevance of the research findings in clinical practice. The relatively small number of eligible studies and the degree of heterogeneity are major limitations of this review. The heterogeneity is further compounded by the diversity of control groups used. The small number of eligible trials limited any meaningful subgroup or sensitivity analyses. The scales used to measure primary and secondary outcome measures are very diverse. Hence, the conclusions that can be drawn from this review are limited. None of the trials included pharmacotherapy as a parallel control. Hence, it is not possible from this review to comment on the relative efficacy of group therapies to antidepressant medication or combined interventions.

Strengths

The search for eligible studies was thoroughly and independently conducted by two researchers (AH and MK). No language barrier was encountered during the analysis. Quality rating was done independently by two researchers (AH and MK). Methodological quality and quality of reporting was done independently by two researchers (AH and MK). As the study included only randomized control with patients having depression at baseline, we are able to provide individual and pooled effect size for group psychotherapy in depression in HIV-infected individuals. Non-depressive outcomes like quality of life, morale, anxiety, and social functioning have been discussed.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

For further research, it is important that clear criteria are developed for diagnosis of depressive disorder in HIV patients that are clinically relevant. None of the studies in the meta-analysis evaluated the curative factors that group offers that individual therapy does not offer from an empirical standpoint. Component analysis and dismantling studies offer the opportunity to tease apart active from inert aspects of group therapy. This type of comparison might yield clue to the relative importance of these two components of group treatment. Further research needs to be conducted in the area of identifying predictors of responsiveness to group therapy. Additional research should also investigate predictors of differential responsiveness to group vs individual modalities.

The number of randomized controlled trials examining psychological intervention is still very limited. A large-scale outcome-focused study with appropriate comparators like pharmacotherapy, individual psychotherapy, Internet Psychotherapy, and bibilotherapy including both men and women participants is warranted to define the efficacy of group psychotherapy in depression in this population. The role of other forms of psychotherapy should also be evaluated. Secondary outcome measures assessing quality of life, disability, feasibility, acceptance of and satisfaction with the therapy should be included. The study design should incorporate qualitative data collection regarding individual preference and attitudes toward treatment. Pragmatic trials of group therapy in diverse settings including those with physical comorbidities are also necessary. The impact of comorbidity on treatment outcome needs to be examined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank Ms Nia Morris, Librarian, Wrexham Maelor Hospital for helping with literature search and Ms Nicola Bagnall for helping in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabkin JG. HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:163–71. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:539–45. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM. The effect of mental illness, substance use, and treatment for depression on the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:233–43. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LB, Towner WJ, Klein DB, Bersoff-Matcha S, et al. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:384–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d53e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vranceanu AM, Safren SA, Lu M, Coady WM, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, et al. The relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to antiretroviral medication adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:313–21. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoni MH, Carrico AW, Durán RE, Spitzer S, Penedo F, Ironson G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral stress management on human immunodeficiency virus viral load in gay men treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:143–51. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195749.60049.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutgendorf SK, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Klimas N, Kumar M, Starr K, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management decreases dysphoric mood and herpes simplex virus-type 2 antibody titers in symptomatic HIV-seropositive gay men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:31–43. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrando SJ, Freyberg Z. Treatment of depression in HIV positive individuals: A critical review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:61–71. doi: 10.1080/09540260701862060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Himelhoch S, Medoff DR. Efficacy of antidepressant medication among HIV individuals with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19:813–22. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanofski J, Croarkin P. Choosing antidepressants for HIV and AIDS Patients: Insights on safety and side effects. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008;5:61–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, Hansen RA, Thieda P, DeVeaugh-Geiss A, Krebs EE, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants: Background paper for the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:734–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-10-200811180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan I, Kong P, Leung P, Au A, Li P, Chung R, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group program for Chinese heterosexual HIV-infected men in Hong Kong. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr GR, Kalichman SC, Morgan MG, Stevenson LY, et al. Outcome of cognitive-behavioral and support group brief therapies for depressed, HIV-infected persons. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1679–86. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Tate DC, Difranceisco W. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a group intervention for HIV positive men and women coping with AIDS-related loss and bereavement. Death Stud. 2004;28:187–209. doi: 10.1080/07481180490276544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: Results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:1038–46. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097344.78697.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodkin K, Blaney NT, Feaster DJ, Baldewicz T, Burkhalter JE, Leeds B. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a bereavement support group intervention in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-seropositive and -seronegative homosexual men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:52–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulder CL, Emmelkamp PM, Antoni MH, Mulder JW, Sandfort TG, de Vries MJ. Cognitive-behavioral and experiential group psychotherapy for HIV-infected homosexual men: A comparative study. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:423–31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steuer JL, Mintz J, Hammen CL. Cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic group psychotherapy in treatment of geriatric depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:180–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haight B, Gibson F, editors. 4th ed. Chapter 18. Boston, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2005. Group Psychotherapy. Burnside's working with older adults: Group process and technique; p. 234. ISBN: 076374770X. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, Schneider LS, Areán PA, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1419–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:249–65. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Mello MF, de Jesus Mari J, Bacaltchuk J, Verdeli H, Neugebauer R. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Amsterdam JD, Salomon RM, O’Reardon JP, et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:417–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuijipers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Are individual and group treatments equally effective in the treatment of depression in adults? A meta analysis. Eur J Psychiatry. 2008;22:38–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vos T, Corry J, Haby MM, Carter R, Andrews G. Cost effectiveness of CBT and drug interventions for major depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:683–92. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Himelhoch S, Medoff D, Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV infected individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:732–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncrieff J, Churchill R, Drummon C, McGuire H. Development of a quality assessment instrument for trials of treatments for depression and neurosis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2001;10:126–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 4.2.6. John Wiley and Sons. 2006. [Last updated 2006 Sep]. Wiley online library: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9780470712184 .

- 29.Moher D, Tetzlaff J, Tricco AC, Sampson M, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruess S, Antoni MH, Hayesc A, Penedo F, Ironson G, Fletcher MA, et al. Changes in mood and depressive symptoms and relatedchange processes during cognitive-behavioral stress management in HIV-infected men. Cognit Ther Res. 2002;26:373–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDermut W, Miller IW, Brown RA. The efficacy of group psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis and review of the empirical research. Clin Psychol Sci Pr. 2001;8:98–116. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zisook S, Peterkin J, Goggin KJ, Sledge P, Atkinson JH, Grant I HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group. Treatment of major depression in HIV-Seropositive men. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:217–24. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]