Abstract

Maternal septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) following amniocentesis is a relatively rare condition, and its incidence is only 0.03~0.19%. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) associated with DIC is also rare. We report here on a 40-year-old female patient who had septic shock and DIC that was complicated by AMI following amniocentesis. The possible mechanism of AMI in this patient may have been coronary artery thrombosis associated with DIC.

Keywords: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, Myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is usually caused by atherosclerosis; however, the occasional patient may develop complete coronary occlusions due to coronary emboli, thrombotic coronary artery disease, vasculitis, primary vasospasm, infiltrative or degenerative diseases, diseases of the aorta, congenital anomalies of coronary arteries or trauma1, 2).

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is characterized by an acute generalized, widespread activation of the coagulation system, and this results in thrombotic complications that are due to the intravascular formation of fibrin as well as to the diffuse hemorrhages that result from the consumption of both the platelets and the coagulation factors. DIC, although sometimes indolent, can cause life-threatening hemorrhage and this condition may require emergency treatment, and DIC is rarely complicated by AMI3-5).

Amniocentesis is a useful prenatal diagnostic modality for various kinds of fetal anomalies. Subclinical intrauterine infections following amniocentesis are reported in up to 0.5% of the patients undergoing this procedure6, 7). However, severe amniotic infection syndrome with a septic shock and DIC complicated by AMI following amniocentesis is very rare8-11).

We report here on a case of a 40-year-old female patient who had septic shock and DIC complicated by AMI following amniocentesis, and we have also included a review of the relevant literature.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old female patient presented to us with dyspnea, fever, chills and hematuria. She was at the 17th week of gestation and amniocentesis had been done 2 days previously for the prenatal evaluation of fetal anomalies at a private clinic. After amniocentesis, she complained of fever, chills, progressive dyspnea, hematuria and abdominal pain. Her systolic blood pressure was less than 80 mmHg. Ultrasonographic examination demonstrated that the fetus had died. Intravenous antibiotics were started and a therapeutic abortion was performed. After this, the patient was transferred to our hospital for the management of her septic complications.

On admission, her blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg, the pulse rate was 105/min, the body temperature was 38.6℃ and the respiration rate was 30/min. Chest auscultation revealed basal rales in both lower lung fields. Vaginal spotting and oliguria were observed.

The complete blood cell count showed leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 28,300/mm3) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 13,000/mm3). The blood chemistry revealed elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase: 645 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase: 170 IU/L), azotemia (blood urea nitrogen: 41.7 mg/dL, creatinine: 3.1 mg/dL) and an increased level of inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 10.1: mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 67 mm/hour). The coagulation profiles showed a prolongation of the prothrombin time (international normalized ratio: 2.63) and the activated partial thrombin time (87 seconds), a low level of fibrinogen level (83 mg/mL), a decreased level of anti-thrombin III (2.81 mg/dL) and increased levels of fibrin degradation products (105.2 µg/mL) and d-dimer (9.65 mg/L). Escherichia coli was isolated from the culture of the amniotic fluid and blood. Therefore, we concluded that the patient had septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) following her intrauterine infection, and this was possibly complicated by the amniocentesis.

Intravenous antibiotics, diuretics and inotropic agents, including dopamine and norepinephrine, were infused continuously. Four units of fresh frozen plasma and 12 units of platelet concentrates per day were infused. Five thousands units of anti-thrombin III per 6 hours were also administered.

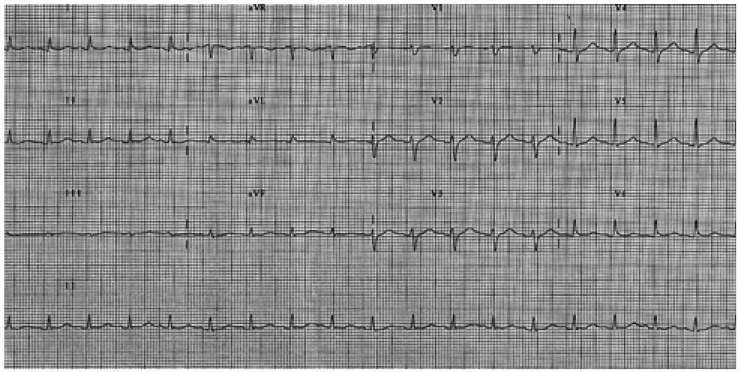

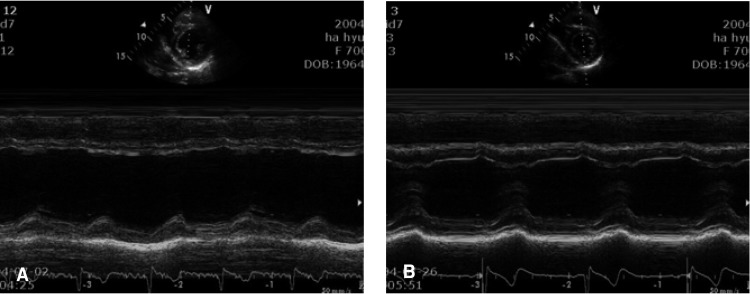

Several hours later after the admission, she complained of continuous substernal and epigastric pain that was associated with cold sweating. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia with non-specific ST segment changes (Figure 1), and the cardiac enzymes were markedly elevated (creatinine kinase: 326 U/L, MB fraction of creatine kinase: 256 U/L, cardiac specific troponin T: 2.17 ng/mL, cardiac specific troponin I: 9.19 ng/mL, myoglobin: 190.2 ng/mL). Trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed the dilated left ventricle (LV) with a chamber size of 60 mm for the end-diastolic dimension; akinesia of the anterior and, septal wall motion and LV systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction: 38%) were also observed (Figure 2A). We could not perform immediate coronary angiography (CAG) due to the oliguria and renal dysfunction, and the patient was treated conservatively for AMI.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia with non-specific ST segment changes.

Figure 2.

(A) Trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed akinesia in the anterior and, septal wall motion and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction = 38%). (B) The follow-up TTE revealed a remarkably improved anterior and septal wall motion and good left ventricular systolic function with a 62% ejection fraction.

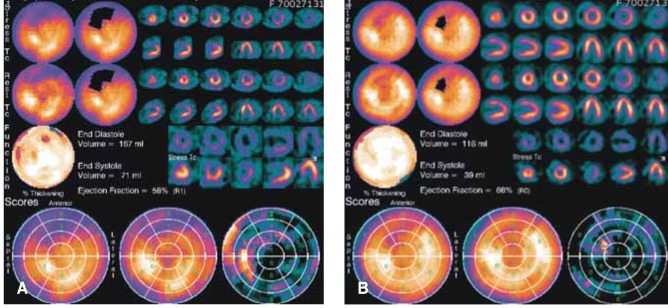

After treatment, the patient's vital signs were stabilized and the subjective symptoms of the patient were improved. However, the thrombocytopenia was not improved for several days despite the replacement of the platelet concentrates, and the renal function progressively deteriorated despite the normalized urine output. On the fourth hospital day, myocardial single photon emission computed tomography (M-SPECT) was performed and the M-SPECT revealed a large, partly reversible perfusion defect in the anterior wall on stress, and the resting image suggesting anterior wall myocardial infarction (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Myocardial single photon emission computed tomography (M-SPECT) revealed a large perfusion defect with partial reversibility in the territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery. (B) Follow-up M-SPECT demonstrated an improved perfusion defect in the territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

The coagulation profiles and thrombocytopenia were normalized on the eighth hospital day. Follow-up TTE was done on the eighth hospital day, and it revealed normalized LV wall motion (Figure 2B). The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine reached their peak levels on the ninth hospital day (blood urea nitrogen: 110.9 mg/dL, creatinine: 8.0 mg/dL) and then they progressively declined. On the thirteenth hospital day, the patient was discharged.

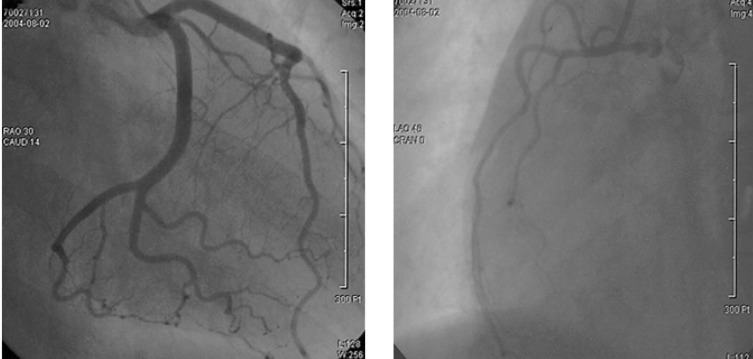

During clinical follow-up at the outpatient clinic, the renal function was normalized at 3 weeks after discharge. The patient was readmitted for diagnostic CAG. The CAG revealed no significant stenosis in both the coronary arteries (Figure 4). Follow-up M-SPECT revealed markedly improved perfusion in the territory of the left anterior descending coronary artery with the remaining perfusion defect (Figure 3B).

Figure 4.

A diagnostic coronary angiogram revealed no significant stenosis in both the coronary arteries.

DISCUSSION

Amniocentesis is a method of prenatal diagnosis that is used for various kinds of fetal anomalies. The complication rate associated with amniocentesis is low, but it increases with a higher maternal age6, 7). Nassar et al.7) have reported that the complication rate of second trimester amniocentesis is 1.6% of 1,347 procedures. The complication rate for fetal loss was 0.22%, the complication rate for bleeding was 0.59% and the complication rate for rupture of the membranes was 0.82%. Subclinical intrauterine infections following amniocentesis are reported to occur in up to 0.5% of the patients. However, severe amniotic infection syndrome with a septic shock and DIC following amniocentesis is very rare and only several cases have been reported on8-11).

AMI usually occurs as a result of thinning and rupture of the fibrous cap of the plaque in obstructed arteries, and this is caused by atherosclerosis; however, the occasional patient may develop complete coronary occlusions due to coronary emboli, thrombotic coronary artery disease, vasculitis, primary vasospasm, infiltrative or degenerative diseases, diseases of the aorta, congenital anomalies of a coronary artery or trauma1, 2).

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is characterized by an acute generalized, widespread activation of the coagulation system, and this results in thrombotic complications that are due to the intravascular formation of fibrin; there can be diffuse hemorrhage as well that is due to the consumption of platelets and coagulation factors. DIC, although it is sometimes indolent, it can cause life-threatening hemorrhage and so may require emergency treatment3-5). In some patients with DIC, AMI may be a possible complication associated with intracoronary thrombi. Yamaguchi et al. have reported on a case of AMI in a patient with relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia in association with DIC12). Upadhyaya et al.13) have reported on a case of snake bite that presented as AMI, ischemic cerebrovascular accident, acute renal failure and DIC. Yamauchi et al.14) have reported on a case of septic shock and DIC in a patient having Legionnaires' disease that was complicated by AMI. Ueda et al.15) have reported the incidence and pathologic features of cardiac lesions in 184 aged, autopsied patients with DIC. According to their study, coronary thrombosis was noted in 31 autopsies (16.8%), fresh myocardial infarction was noted in 16 autopsies (8.7%), and massive myocardial hemorrhage in 49 autopsies (26.6%). The proposed mechanism of AMI in patients with DIC is the formation of coronary thrombi. In our case, the formation and spontaneous dissolution of intracoronary thrombi might have been a possible explanation of the patient's AMI because the LV function of the patient was improved by conservative management, and the CAG revealed no fixed coronary stenosis. Other possible causes of AMI in this patient might have been a spasm and/or myocarditis associated with sepsis.

The medical treatment of AMI associated with DIC and sepsis is very difficult. Because of the low platelet count, the use of anti-platelet agents such as aspirin or clopidogrel is limited and because of the bleeding risk, anti-thrombotic treatment is also limited. In our patient, any anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic therapy was not applied. DIC and sepsis are usually complicated by shock and multi-organ failure including oligoanuria and acute renal failure. Thus, the use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or beta-blocker and CAG in these patients is contra-indicated.

In summary, we report here on a case of a 40-year-old female patient who had septic shock and DIC that was complicated by AMI following amniocentesis, and we also include a review of the literature. AMI should be considered as a possible complication in a patient with DIC who presents with chest pain.

References

- 1.Waller BF. Atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic coronary artery factors in acute myocardial infarction. In: Pepine CJ, editor. Acute myocardial infarction. Philadelphia: Davis; 1989. pp. 29–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheitlin MD, McAllister HA, de Castro CM. Myocardial infarction without atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1975;231:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tayler FB, Jr, Kinasewitz GT. The diagnosis and management of disseminated untravascular coagulation. Curr Hematol Rep. 2002;1:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slofstra SH, Spek CA, ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hematol J. 2003;4:295–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. New treatment strages for disseminated intravascular coagulation based on current understanding of the pathophysiology. Ann Med. 2004;36:41–49. doi: 10.1080/07853890310017251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turhan NO, Eren U, Seckin NC. Second-trimester genetic amniocentesis: 5-year exprience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271:19–21. doi: 10.1007/s00404-004-0635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nassar AH, Martin D, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Gomez-Marin O, Salman F, Gutierrez A, O'Sullivan MJ. Genetic amniocentesis complications: is the incidence overrated? Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;58:100–104. doi: 10.1159/000078793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamanishi J, Itoh H, Sagawa N, Nakayama T, Yanmada S, Nakamura K, Saito A, Kumukura E, Yura S, Fujii S. A case of successful management of maternal septic shock with multiple organ failure following amniocentesis at midgestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2002;28:258–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2002.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamoda H, Chamberlain PF. Clostridium welchii infection following amniocentesis: a case report and review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:783–785. doi: 10.1002/pd.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elchalal U, Shachar IB, Peleg D, Schenker JG. Maternal mortality following diagnostic 2nd-trimester amniocentesis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19:195–198. doi: 10.1159/000075150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovav Y, Hornstein E, Pollak RN, Yaffe C. Sepsis due to Clostrium perpringens after second trimester amniocentesis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:235–236. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi M, Murata R, Kawamura A, Ueda M. Acute myelogenousleukemia associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute myocardial infarction at relapse. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2001;42:716–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Upadhyaya AC, Murthy GL, Sahay RK, Srinivasan VR, Shantaram V. Snake vite presenting as acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic cerebrovascular accident, acute renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:1109–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamauchi T, Yamamoto S, Fukumoto M, Oyama N, Nakano A, Nakayama T, Iwasaki H, Shimizu H, Tsutani H, Lee JD, Okada K, Ueda T. Early manifestation of septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation complicated by acute myocardial infarction in a patient suspected of having Legionnaires' disease. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1998;72:286–292. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.72.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda K, Suigura M, Ohkawa S, Hiraoka K, Mifune J, Matsuda T, Murakami M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in the aged complicated by acute myocardial infarction. Jpn J Med. 1981;20:202–210. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine1962.20.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]