Abstract

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a commonly performed surgery for the treatment of spondylosis, radiculopathy, myelopathy, and trauma to the cervical spine. Esophageal perforation is a rare yet serious complication following ACDF with an incidence of 0.02 to 1.52%. We describe a case of a 24-year-old man who underwent ACDF and corpectomy following a motor vehicle accident who subsequently developed delayed onset esophageal perforation requiring surgical intervention. We believe that the detailed review of the surgical management of esophageal perforation following cervical spine surgery will provide a deeper understanding for the Intensivist in regards to postoperative airway management in these types of patients. Careful extubation over a soft flexible exchange catheter should take place to help reduce the risk of perforation in the event reintubation is required.

Keywords: Airway management, anterior cervical discectomy and Fusion, corpectomy, esophageal perforation

INTRODUCTION

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion is a commonly performed surgery for the treatment of spondylosis, radiculopathy, myelopathy, and trauma. Esophageal perforation is an exceedingly rare complication following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF). The incidence of these complications ranges from 0.02 to 1.52% although is higher when it is a result of trauma.[1,2,3,4,5,6] We describe a case of a 24-year-old man who underwent ACDF and corpectomy following a motor vehicle accident who developed delayed onset aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia requiring surgical repair of an esophageal perforation. To the best of our knowledge there has been no prior literature discussing airway management in patients who underwent esophageal repair for perforation following cervical spine surgery. We believe this paper will provide a deeper understanding to the Intensivist in regards to postoperative airway management in this type of patient.

CASE REPORT

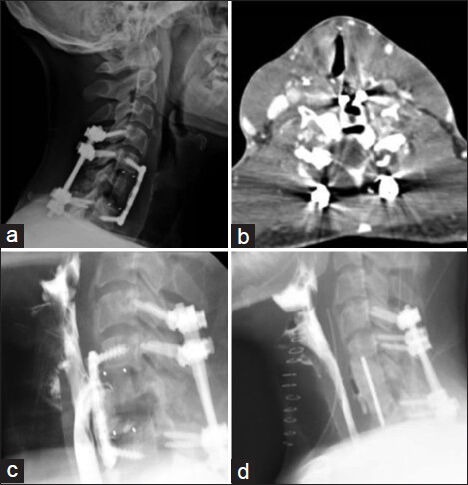

A 24-year-old man presented to an outside hospital following a motor vehicle accident with cervical spine fractures of C5 - C7, anterolisthesis of C6 and associated spinal cord transection with resulting quadriplegia. The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) of C5-7, C6 corpectomy with polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cage and C4 - T1 posterior fusion [Figure 1a]. Postoperatively the patient did well and was discharged to a rehabilitation center at our institution.

Figure 1.

Lateral cervical x-ray shows C4-T1 posterior fusion with C5-C7 ACDF and PEEK cage at the level of C6 with no apparent hardware defects (a) CT neck demonstrated air surrounding the implant at C6 as well as the anterior fusion plate (b) Barium swallow study showed a posterior esophageal barium leak at C5-C6 and a TE-fistula. The contents of the fistula are seen tracking inferiorly T1 and is seen anterior to the fusion plate (c) Barium swallow study done ten days postoperatively shows resolution of perforation (d)

Approximately four months following his surgeries the patient began to develop increased sputum production, cough and fever. Chest X-ray revealed bilateral infiltrates consistent with aspiration pneumonia. At this time, the aspiration was thought to be due to the patient's poor pulmonary clearance from his immobility and quadriplegia. While on antibiotic therapy for aspiration pneumonia the patient developed acute dysphagia. Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated air surrounding the implant at C6 as well as the anterior fusion plate [Figure 1b]. Upper endoscopy and bronchoscopy did not demonstrate any esophageal or airway defects. Barium swallow revealed an esophageal defect with contrast tracking down the prevertebral space to the level of T1 anterior to the cervical fusion plate as well as a tracheo-esophageal fistula [Figure 1c].

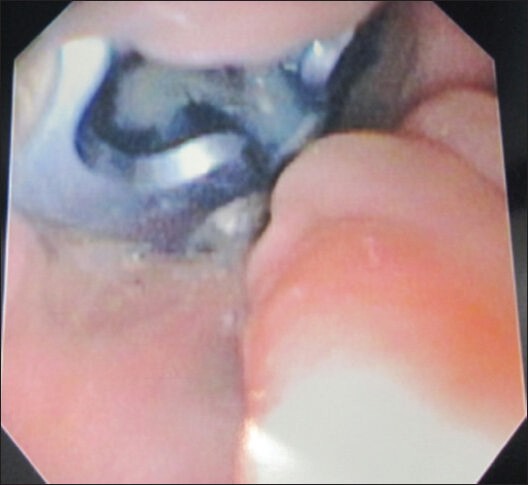

The patient underwent removal of the anterior plate, which was visualized in the pharyngoesophagus during intraoperative video-assisted laryngoscopy,[2] removal of PEEK cage and placement of antibiotic impregnated bone cement, primary repair in conjunction with a sternocleidomastoid muscle flap being placed on the esophageal defect [Figure 2]. Although the barium swallow study revealed a tracheoesophageal fistula, none was seen intraoperatively. A nasogastric tube (NGT) was placed under direct endoscopic visualization as well. Postoperatively, the patient remained intubated with the NGT to remain in place for one week. The patient was extubated over a soft 22-french exchange catheter without incident and repeat barium swallow study demonstrated resolution of the esophageal perforation [Figure 1d].

Figure 2.

Intraoperative video-assisted laryngoscopic view revealing the anterior cervical plate within the pharyngoesophagus

DISCUSSION

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has been the mainstay treatment of patients with radiculopathy or myelopathy attributed to cervical spine disease, particularly herniated nucleus pulposus.[6,7] In the trauma setting, vertebral body fracture may require corpectomy in which ACDF is typically performed in conjunction with posterior instrumentation.[2,6]

Esophageal perforation is a more rare and potentially life threatening complication occurring in 0.02-1.52% of patients.[1,2,4] The mortality rate in such instances has been reported as high as 19%.[4] Identifying patients with esophageal perforation can be difficult as the clinical presentation and initial onset is highly variable. Presentation with dysphagia, choking, aspiration, pain, fever or subcutaneous emphysema can all be postoperative complaints typically seen in up to 9.5% of patients.[2,5,8]

The placement of an anterior cervical plate improves fusion rates and reduces risk of graft migration.[4] Delayed esophageal perforation is typically secondary to suboptimal instrumentation placement or failure. Additionally, chronic compression of the esophagus against the anterior cervical plate during swallowing can result in pressure necrosis and eventually perforation and fistula formation.[2,4,5,7]

Diagnosis of esophageal perforation can be challenging due to the delayed and variable clinical presentation. In addition to computed tomography (CT) scan, upper endoscopy, barium contrast studies, and bronchoscopy are the most informative studies to determine the location and extent of perforation.[4,6,9,10]

Proper management of esophageal perforation is very important as its associated mortality rate is high. A conservative approach including nil per os (NPO), with temporal parenteral nutrition by either NG or PEG tube and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics may be appropriate in a very select group of patients where perforation is incidentally found and are asymptomatic.[4] Spontaneous healing of these injuries may take four to twelve weeks however, this conservative approach is associated with a 20 - 45% rate of abscess formation.[1,4,9] Surgical management provides definitive treatment. The use of a sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle flap has been considered the gold standard to achieve and maintain perforation closure as without it esophageal sutures will invariably fail.[1] The SCM is a highly mobile and vascularized medium that can improve antibiotic delivery, wound healing and provides a physical barrier between the esophagus and the cervical spine.[1,2,4,5]

Important considerations when extubating is the degree of healing following esophageal perforation repair, mallampati grade, as well as the possible need and risks of reintubation in an airway emergency. Although most reports describe waiting approximately 10-14 days postoperatively before resuming oral feeds, our patient was successfully extubated and tolerated oral feeds suggesting this period of time to be sufficient for would healing.[7,10,11,12] In our patient, the NGT remained in place for one week prior to the patient being extubated. Although rare, esophageal perforation can occur following accidental esophageal intubation and is of clear concern in patients who underwent esophageal repair.[10,11,12,13] Risk of perforation is higher when inexperienced individuals attempt intubation, difficult intubation requiring multiple attempts, as well as in emergency scenarios.[13] When the patient has satisfied all weaning parameters and has a present cuff leak we strongly recommend that an experienced anesthesiologist be present for extubation and have all appropriate airway devices available including a fiberoptic bronchoscope. Additionally, the patient should be extubated over a soft flexible 22-french exchange catheter. The more rigid and thicker bougie should be avoided due to their risk of trauma. A small hole should be made in the facemask such that the exchange catheter may pass through while the patient receives 8-10 L of oxygen for typically 30-60 minutes. This will allow for a more controlled and safer reintubation in the event the patient fails extubation and therefore reduce the potential risk of reperforation.

CONCLUSION

Esophageal perforation following cervical spine surgery is a rare yet serious complication. Greater vigilance is required in the event reintubation is required as perforation of the surgical repair site is of great concern. Therefore, it is our recommendation that an experienced anesthesiologist be present for extubation and that all appropriate airway devices are available including a fiberoptic bronchoscope.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn SH, Lee SH, Kim ES, Eoh W. Successful repair of esophageal perforation after anterior cervical fusion for cervical spine fracture. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dakwar E, Uribe JS, Padhya TA, Vale FL. Management of delayed esophageal perforations after anterior cervical spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:320–5. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.SPINE08522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haku T, Okuda S, Kanematsu F, Oda T, Miyauchi A, Yamamoto T, et al. Repair of cervical esophageal perforation using longus colli muscle flap: A case report of a patient with cervical spinal cord injury. Spine J. 2008;8:831–5. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navarro R, Javahery R, Eismont F, Arnold DJ, Bhatia NN, Vanni S, et al. The role of the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap for esophageal fistula repair in anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E617–22. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000182309.97403.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phommachanh V, Patil YJ, McCaffrey TV, Vale F, Freeman TB, Padhya TA. Otolaryngologic management of delayed pharyngoesophageal perforation following anterior cervical spine surgery. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:930–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Scherer MA. Late hypopharyngo-esophageal perforation after cervical spine surgery: Proposal of a therapeutic strategy. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:880–6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo YC, Levine MS. Erosion of anterior cervical plate into pharynx with pharyngotracheal fistula. Dysphagia. 2010;25:334–7. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Nikolakakos LG, Smisson HF, Johnston KW, Grigorian AA, et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2310–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318154c57e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaudinez RF, English GM, Gebhard JS, Brugman JL, Donaldson DH, Brown CW. Esophageal perforations after anterior cervical surgery. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:77–84. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200002000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jougon J, Cantini O, Delcambre F, Minniti A, Velly JF. Esophageal perforation: Life threatening complication of endotracheal intubation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu DC, Theodore P, Korn WM, Chou D. Esophageal erosion 9 years after anterior cervical plate implantation. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:310–2. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solerio D, Ruffini E, Gargiulo G, Camandona M, Raggio E, Solini A, et al. Successful surgical management of a delayed pharyngo-esophageal perforation after anterior cervical spine plating. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:S280–4. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0578-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilmi IA, Sullivan E, Quinlan J, Shekar S. Esophageal tear: An unusual complication after difficult endotracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:911–4. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000077074.66151.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]