Abstract

Renal intercalated cells mediate the secretion or absorption of Cl− and OH−/H+ equivalents in the connecting segment (CNT) and cortical collecting duct (CCD). In so doing, they regulate acid-base balance, vascular volume, and blood pressure. Cl− absorption is either electrogenic and amiloride-sensitive or electroneutral and thiazide-sensitive. However, which Cl− transporter(s) are targeted by these diuretics is debated. While epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) does not transport Cl−, it modulates Cl− transport probably by generating a lumen-negative voltage, which drives Cl− flux across tight junctions. In addition, recent evidence indicates that ENaC inhibition increases electrogenic Cl− secretion via a type A intercalated cells. During ENaC blockade, Cl− is taken up across the basolateral membrane through the Na+-K+−2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1) and then secreted across the apical membrane through a conductive pathway (a Cl− channel or an electrogenic exchanger). The mechanism of this apical Cl− secretion is unresolved. In contrast, thiazide diuretics inhibit electroneutral Cl− absorption mediated by a Na+-dependent Cl−/HCO3− exchanger. The relative contribution of the thiazide and the amiloride-sensitive components of Cl− absorption varies between studies and probably depends on the treatment model employed. Cl− absorption increases markedly with angiotensin and aldosterone administration, largely by upregulating the Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchanger pendrin. In the absence of pendrin [Slc26a4(−/−) or pendrin null mice], aldosterone-stimulated Cl− absorption is significantly reduced, which attenuates the pressor response to this steroid hormone. Pendrin also modulates aldosterone-induced changes in ENaC abundance and function through a kidney-specific mechanism that does not involve changes in the concentration of a circulating hormone. Instead, pendrin changes ENaC abundance and function, at least in part, by altering luminal HCO3−. This review summarizes mechanisms of Cl− transport in CNT and CCD and how these transporters contribute to the regulation of extracellular volume and blood pressure.

Keywords: Slc26a4, Pds, Cl−/HCO3− exchange, ENaC, pendrin, intercalated cells, blood pressure

distal nephron nacl transport is crucial to the renal regulation of extracellular volume. During volume contraction, distal nephron NaCl absorption increases, which restores extracellular volume to basal levels. Conversely, during volume overload, distal nephron NaCl absorption appropriately falls. Genetically defined models of hypertension are often associated with expanded extracellular volume due to derangements in distal NaCl transporters, which inappropriately increases distal NaCl absorption. Therefore, “essential” hypertension may result from occur as-of-yet-unrecognized, inherited transport defects in this region of the nephron.

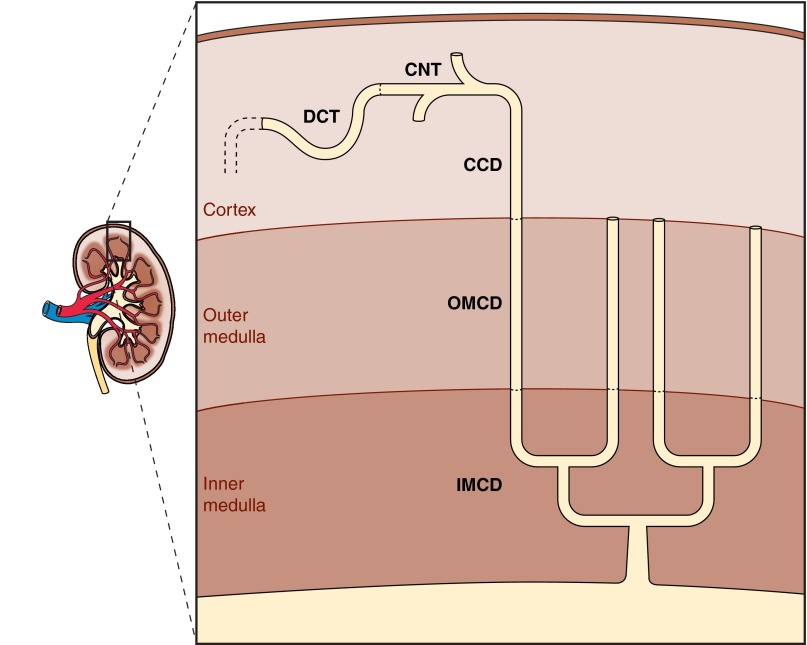

The bulk of distal NaCl transport occurs in the cortex, within the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), connecting segment (CNT), and cortical collecting duct (CCD). However, the medullary collecting duct performs the final regulation of NaCl balance. The structure of the rat distal nephron is shown in Fig. 1. In this region, 36,000 DCTs transition to CNT and then merge in arcades to form ∼7,200 CCDs (41). The “distal tubule” employed in micropuncture studies localizes to the superficial cortex and is made up of CNTs, which are branched, and DCTs, which are unbranched. Solute transport within these segments has been quantified using a variety of techniques, including micropuncture and electrophysiology of rat DCT and CNT as well in rat and rabbit CCDs perfused in vitro. More recently, these techniques have been extended to the study of genetically modified mice. In so doing, changes in solute transport can be quantified following the ablation of individual transporters or ablation of various components of a signaling pathway, thereby establishing the physiological significance of these transporters and/or signaling pathways.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of distal nephron composition. The distal nephron consists of 1-mm distal convoluted tubule (DCT), 2 mm connecting tubule (CNT), 2-mm cortical collecting duct (CCD), 2-mm outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD), and 5-mm inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD). Within CNT, the 36,000 tubules coalesce linearly to form 7,200 CCD. Within IMCD, the tubules coalesce exponentially so that final urine flows through only 113 papillary collecting ducts (110).

Na+ absorption by the CCD and CNT is critical not only for NaCl balance but also for the regulation of K+ and H+ secretion. To facilitate the bookkeeping for all aspects of NaCl absorption, mathematical models of the distal nephron segments were developed. By collating data generated by a number of laboratories, these models stitched together an integrated picture NaCl transport by the cortical distal nephron (109). While comprehensive reviews have focused on NaCl transport within DCT (68) and on Na+ transport by principal cells of CNT and CCD (25), this review focuses instead on the loci and regulation of Cl− transport within the CNT and CCD.

NaCl Transport in the Micropuncture-Defined Distal Tubule

“Distal delivery” refers to flow at the most proximal portion of the DCT that is accessible to micropuncure. Distal Na+ delivery should be just below 10% of the filtered load, assuming that early distal volume flow rate is ∼20% of the glomerular filtration rate and that luminal Na+ concentration is just slightly less than half that of plasma (11, 14, 22, 35, 52, 86). Of the 10% of the filtered load that reaches the most proximal portion of the DCT, ∼75% is absorbed before reaching the collecting duct. Therefore, ∼6–8% (or three-fourths of 10%) of the filtered load is absorbed along the DCT and CNT. This component of the filtered load of Na+ is absorbed more or less equally along the early and late portions of the accessible distal tubule (10). Therefore, 3–4% of filtered Na+ load is absorbed along the 1-mm length of the DCT and another 3–4% of the filtered Na+ load is absorbed along the 1-mm length CNT. This implies a Na+ transport rate of 170 pmol·min−1·mm−1 along the CNT and DCT, which is about half the transport rate observed in rat proximal tubule (Table 1). The rates of Na+ absorption, however, are dependent on filtered load and can vary severalfold. Na+ absorption depends on luminal NaCl concentration in both early and late segments, although Cl− absorption is sensitive to luminal NaCl only in the early segment (16). K+ secretion occurs primarily in late segments (96) and can be a substantial fraction of Na+ flux. K+ secretion is also dependent on the anion composition of the luminal fluid. For example, K+ secretion doubles when gluconate is substituted for Cl− in the luminal solution (96).

Table 1.

Solute flux rates obtained from early and late distal microperfusion of rat kidney

| Perfusion, nl/min |

Perfusate Concentrations, mM |

Early Reabsorption, pmol·min−1·mm−1 |

Late Reabsorption, pmol·min−1·mm−1 |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | LT | Na | K | Cl | HCO3− | Na | K | Cl | HCO3− | Na | K | Cl | HCO3− | Condition | Reference No. |

| 5.9 | 6.4 | 80 | 2 | 87 | 0 | 123 | 143 | Costanzo (10) | |||||||

| 12.8 | 13.3 | 75 | 2 | 68 | 0 | 68.1 | 115 | 66.9 | 112 | Ellison et al. (16) | |||||

| 9.7 | 9.3 | 150 | 4.5 | 110 | 25 | 276 | 345 | 113 | 103 | Ellison et al. (16) | |||||

| 9.8 | 150 | 4.5 | 110 | 25 | 105 | 154 | Ellison et al. (16) | ||||||||

| 10.2 | 150 | 4.5 | 0 | 25 | 5.5 | −238 | Gluconate | Ellison et al. (16) | |||||||

| 12.8 | 13.3 | 75 | 2 | 68 | 0 | −12.8 | −61.4 | Velazquez et al. (96) | |||||||

| 13.2 | 14.5 | 75 | 2 | 0 | 0 | −26.4 | −110 | Gluconate | Velazquez et al. (96) | ||||||

| 10.1 | 9.8 | 150 | 4.5 | 110 | 25 | −9.3 | −49.3 | Velazquez et al. (96) | |||||||

| 12.3 | 12.3 | 75 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 29.2 | 28.6 | Wang et al. (105) | |||||||

| 12.4 | 12.2 | 70 | 2 | 59 | 15 | 32.9 | 10.7 | Wang et al. (105) | |||||||

| 12.1 | 12.1 | 70 | 2 | 59 | 15 | 150 | −54.1 | 106 | −88.3 | Wang and Giebisch (104) | |||||

| 12.2 | 12.1 | 70 | 2 | 59 | 15 | 264 | −59.3 | 208 | −40.7 | ANG II | Wang and Giebisch (104) | ||||

| 12.3 | 12.3 | 70 | 2 | 59 | 15 | 33.3 | 14.6 | Wang and Giebisch (104) | |||||||

| 12.0 | 12.1 | 70 | 2 | 59 | 15 | 62.6 | 17.1 | ANG II | Wang and Giebisch (104) | ||||||

| 8.2 | 56 | 2 | 26 | 28 | −14 | 18 | Levine et al. (49) | ||||||||

| 8.1 | 56 | 2 | 26 | 28 | −18 | 45 | ANG II | Levine et al. (49) | |||||||

| Stationary | 125 | 5 | 107 | 25 | 26.0 | 10.5 | Bareto-Chaves and Mello-Aires (3) | ||||||||

| Stationary | 125 | 5 | 107 | 25 | 74.0 | 73.0 | ANG II | Bareto-Chaves and Mello-Aires (3) | |||||||

ET and LT, early and late segments, respectively.

The mechanism of ion transport in the distal nephron and collecting duct was examined in greater detail in studies that employed CCDs perfused in vitro. While most initial work was done in rabbit tubules, several studies were done in rat CCD. With the explosion in genetically modified mice, this technique has been applied much more in recent years to the study of mice. Data from these studies are summarized in Table 2. The salient observation is that Na+ transport in the CCD is variable and greatly depends on hormonal stimulation of the tubule. Moreover, Na+ absorption in the CCD is only about half of that found in the CNT, even when stimulated. K+ secretion is also variable and highly regulated by aldosterone. K+ secretion may be much smaller than Na+ flux, making NaCl absorption dominant. Conversely, K+ and Na+ flux may be similar in magnitude, such that Na+/K+ countertransport is dominant. Because CNTs merge to become the CCD, total tubule length in vivo is sixfold greater in the CNT than in the CCD. Collectively, these data strongly suggest that NaCl absorption and K+ secretion in vivo are at least an order of magnitude greater in the CNT than that in CCD.

Table 2.

Solute flux rates measure in isolated perfused cortical collecting ducts of rat kidney

| Perfusate Concentrations, mM |

Condition |

Absorption, pmol·min−1·mm−1 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusion, nl/min | Na | K | Cl | HCO3− | AVP | Aldo | Na | K | Cl | HCO3− | Reference |

| 1.7 | 144 | 4.0 | 118 | 25 | + | + | 48.3 | 12.2 | Tomita et al. (93) | ||

| 1.7 | 146 | 4.0 | 118 | 25 | + | + | 51 | −12 | Tomita et al. (94) | ||

| 6–12 | 136.3 | 5.0 | 139 | 3.5 | + | 18.9 | −7.6 | Schafer and Troutman (75) | |||

| + | 14.3 | −13.7 | Schafer and Troutman (75) | ||||||||

| + | + | 93.3 | −41.9 | Schafer and Troutman (75) | |||||||

| 10–20 | 90.8 | 5.0 | 97 | 3.6 | + | 22 | Chen et al. (9) | ||||

| + | 38 | Chen et al. (9) | |||||||||

| + | + | 152 | Chen et al. (9) | ||||||||

| 1.9 | 148 | 5 | 105 | 25 | 18.3 | Gifford et al. (26) | |||||

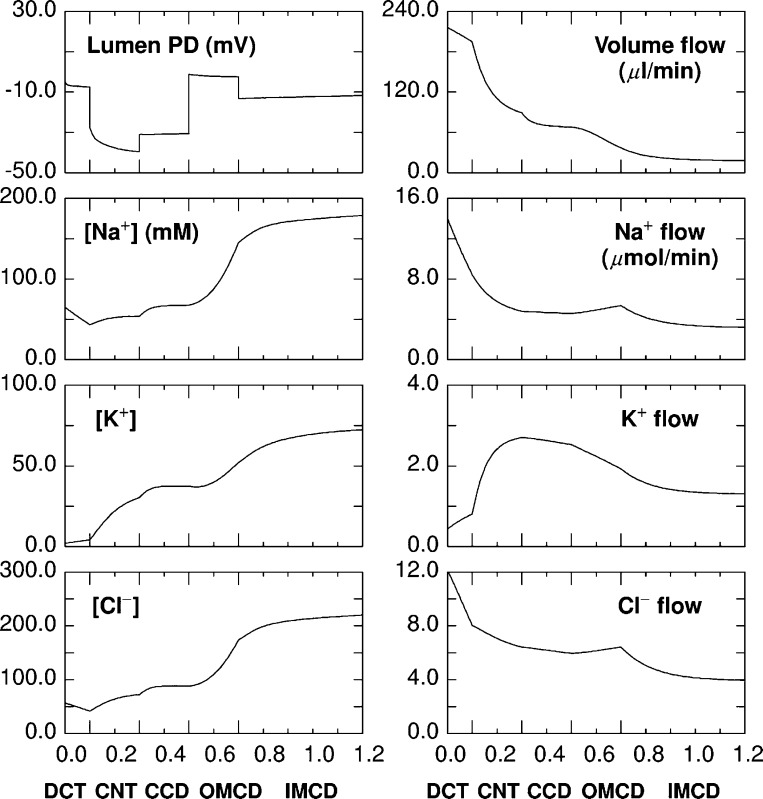

Each of the distal nephron segments from rat kidney have been simulated in mathematical models, which represent the fluxes and permeabilities of Na+, K+, Cl−, and H+/OH− equivalents (110–114). These segmental models were subsequently integrated into a model of the full distal nephron. Luminal solute concentrations and flows predicted by the model are displayed in Fig. 2 (109). The model predicts that the bulk of the cortical NaCl absorption occurs in the DCT and CNT and that virtually all distal K+ secretion occurs in the CNT. Much lower rates of Na+ absorption are expected within the CCD relative to the CNT, since the CCD has a low luminal Na+ concentration and a high lumen-negative transepithelial voltage, which should reduce Na+ absorption. Moreover, the high luminal K+ concentration expected in the CCD should greatly attenuate K+ secretion in this segment. Net Cl− transport in the CCD is also predicted to be much lower in the CCD than in the CNT. However, the CCD likely has an important role in fine-tuning distal NaCl absorption and K+ secretion and is an important experimental model for examining distal nephron transport.

Fig. 2.

Model prediction of distal nephron electrolyte transport for a single rat kidney. The x-axis for all panels displays distance along the tubules (cm). Elongated tic marks denote boundaries of the DCT, CNT, CCD, OMCD, and IMCD. Left: include transepithelial voltage and the luminal concentrations of Na+, K+, and Cl−. Right: axial flows of volume (μl/min) and solutes (μmol/min) for the ensemble of nephrons (110).

Paracellular Cl− Absorption in the CCD and CNT

While principal cells mediate electrogenic Na+ absorption through the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC; Ref. 25), transepithelial Cl− absorption is thought to be both paracellular (via tight junctions) and transcellular (across intercalated cells; Ref. 62). Paracellular Cl− flux is electrogenic and driven by transepithelial electrical potential. However, the quantitative importance of paracellular Cl− transport in CNT and CCD is uncertain, in part due to the changing ion concentrations along the tubule and due to the difficulty of dissecting CNTs and making these measurements. ENaC mediates Na+ absorption across the apical membrane of principal cells, which provides the driving force for K+ secretion through luminal K+ channels (25). The lumen-negative potential generated by ENaC also provides a driving force for Cl− absorption across tight junctions and lateral intercellular spaces (106). ENaC inhibitors, such as amiloride or benzamil, eliminate the lumen-negative transepithelial voltage, which is thought to reduce Cl− absorption by eliminating the driving force for paracellular Cl− absorption (74, 106).

By freeze-fracture or transmission electron microscopy, tight junctions appear as fusions of opposing plasma membrane (40). Tight junctions are made up of transmembrane proteins that include occludins, claudins, and junctional adhesion molecules (31). Claudins interact with the cell membrane and between adjacent cells to form strands within tight junctions (30). Within the mouse and human kidney, claudins 3, 4, 7, 8, and 18 are found in the connecting tubule and in the collecting duct (30, 40). Claudins form both a paracellular barrier and a paracellular pore (30, 34). Claudin 4 is thought to be a pore claudin since knockdown of this protein reduces paracellular permeability and increases transepithelial resistance in heterologous expression systems (30). In contrast, claudin 7 is considered to be a barrier claudin since knockdown of this protein reduces transepithelial resistance in heterologous expression systems (30, 34). Moreover, mice with genetic ablation of claudin 7 have severe renal salt wasting, which may be due to compromised barrier function of renal tight junctions (90). However, since most of these studies were done in cell culture and since the effect of claudin expression on transepithelial resistance and paracellular permeability depends on the cell line used to overexpress these claudins (30), additional studies in native tissue are needed.

Certain mutations in the serine theonine kinases with no lysines WNK1 and WNK4 produce pseudohypoaldosteronism (PHAII), a condition associated with hypertension and hyperkalemia. WNK4 modulates blood pressure and K+ homeostasis, in part, by upregulating transporters involved in the transepithelial transport of Na+, Cl−, and K+, such as the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter and the renal outer medullary K+ channel ROMK (23). However, WNK4 also regulates paracellular Cl− transport in cultured cells (34). WNK4 localizes to tight junctions within the DCT and collecting duct, where it is thought to modulate paracellular Cl− permeability, in part, by phosphorylating claudins 1–4 (30) and by phosphorylating claudin 7 at Ser206 (89). However, not all studies have demonstrated phosphorylation of claudin 4 by WNK4 (30). Moreover, collecting duct Cl− permability is unchanged in mouse models of PHAII (30). Therefore, the role of WNK kinases and claudins the regulation of paracellular Cl− permeability requires further study, particularly in native tissue (30).

The extent to which these tight junction proteins modulate Cl− absorption in native tissue is not fully understood. In rabbit CCD, Sansom and O'Neil (73) observed that chronic aldosterone administration reduces tight junction electrical conductance, which decreases paracellular backleak of Na+ from blood to lumen. The result is a “tighter epithelium,” which reduces paracellular Cl− absorption and increases K+ secretion, despite the increase in total Cl− absorption that follows the administration of aldosterone in vivo (62).

The quantitative importance of tight junctional Cl− flux depends on the permeability of this pathway. In turn, permeability depends on the relationship of ion flux to its electrochemical driving force. In renal epithelial models, paracellular ion flux, J (mmol/s·cm2) is calculated from the Goldman relation:

where Cα and Cβ are luminal and peritubular ion concentrations (mM), h (cm/s) is the tight junctional ion permeability, and (Ψα − Ψβ) is the transepithelial electrical potential difference (mV). In this formulation, ζ is a normalized electrical potential, obtained by application of the ion valence, z = −1, the Faraday, F = 96.5 C/mmol, and the product of the gas constant and absolute temperature, RT = 2.57 J/mmol. With this notation, the ionic current, I = zFJ, and the ionic conductance, G (mS/cm2) is

Therefore, while permeability is a basic attribute of the permeation pathway, conductance depends on the ambient solute concentrations and the electrical potential itself. This formula allows translation between electrophysiologic conductance measurements and solute permeability determinations.

Mathematical models of rabbit (88) and rat CCD (110) predict that the low luminal Na+ concentration observed experimentally is critically dependent on a very low tight junctional Na+ permeability. However, tight junctional permeability is difficult to quantify, particularly under physiological conditions. Junctional conductance was measured in the rabbit, and rat CCD has been used to predict paracellular NaCl transport. CCD tight junctions are slightly more selective for Cl− than Na+, since the Cl−-to- Na+ conductance ratio is about 1.2–1.3 (74, 106), and total junctional conductance is higher in rat than in rabbit CCD (i.e., 11–13 vs. 1.2–1.3 mS/cm2; Refs. 45, 55, 57, 74, 106). Permeability is also greater for Cl− than Na+ in both rat and rabbit CCD (75, 77). The model of rat CCD (110) employed a tight junctional Cl− permeability of 6 × 10−6 cm/s, which yields a Cl− conductance of 2.5 mS/cm2. Junctional permeabilities of rat CNT were taken to be twice those measured in the CCD (112). With the use of these values, Cl− absorption in the rat CNT was predicted to be 1.5 μmol/min for the ensemble of coalescing tubules, which is ∼35 pmol·min−1·mm−1 per tubule. If one assumes that luminal Cl− concentration is about half that of plasma and that transepithelial voltage is approximately −32 mV, the model predicts that ∼50% of CNT Cl− absorption is paracellular, while the other 50% is transcellular. However, because junctional permeability can only be estimated and because luminal Cl− concentration along the CNT is variable, the magnitude of the paracellular and transcellular components of Cl− absorption in the CNT is not precisely known. For rat CCD, the model predicts that as luminal Cl− increases from 36 to 80 mM along the length of the tubule, tight junctional Cl− flux will increase from 2.9 to 19.2 pmol·min−1·mm−1 while transepithelial flux of Cl− across the type B cell will remain relatively constant at 5.4 pmol·min−1·mm−1 (110). Thus the model predicts that transepithelial transport of Cl− across type B cells is similar in magnitude to that of tight junctional Cl− flux in rat CCD.

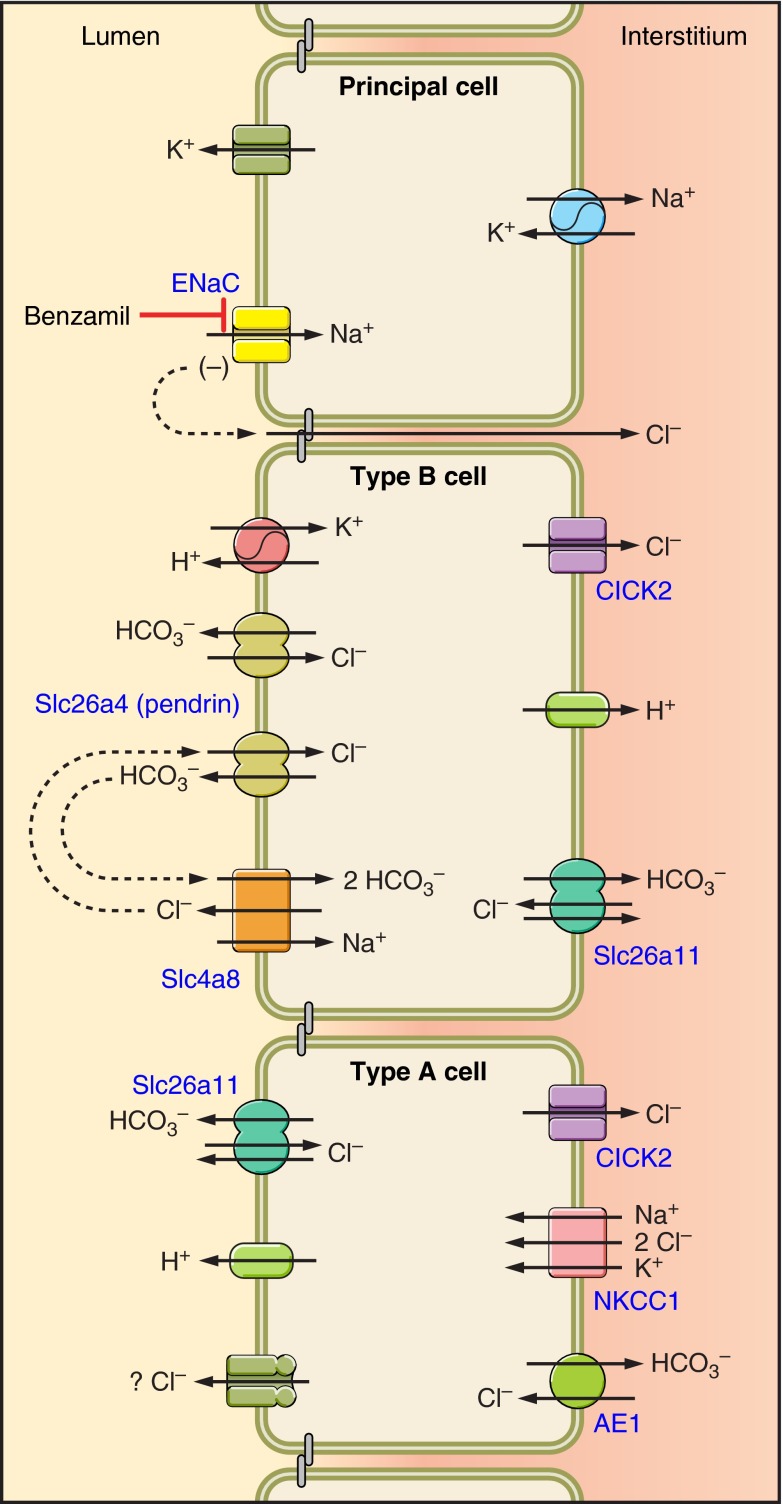

Cell Types and Transporters Present in the CCD

The rodent CCD is made up of two cell types: principal and intercalated cells. Intercalated cells are classified as type A, type B, or non-A, non-B cells based on the expression of the Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, AE1, and the subcellular distribution of the H+-ATPase within the cell (1, 7, 37, 91) (Fig. 3). The distribution of these transporters predicts whether an intercalated cell secretes H+ or OH− equivalents (18, 79). Type A intercalated cells secrete H+ equivalents through the apical plasma membrane H+-ATPase (1, 91), which acts in series with a kidney-specific splice variant of the red cell anion exchanger (AE1) expressed on the basolateral plasma membrane (1). These transporters are upregulated during metabolic acidosis (4, 21), which increases secretion of H+ equivalents, thereby attenuating the acidosis.

Fig. 3.

Cell types in the cortical collecting duct and the connecting tubule: this Fig. displays the distribution of ion transporters within intercalated and principal cells in the mouse CCD. Intercalated cells are identified on the basis of anion exchanger 1 (AE1) expression and the subcellular distribution of the H+-ATPase. Type A intercalated cells express the H+-ATPase on the apical plasma membrane and the Cl−/HCO3− exchanger AE1 on the basolateral plasma membrane. Type B and non-A, non-B intercalated cells express pendrin in the region of the apical plasma membrane. However, B cells express the H+-ATPase on the basolateral plasma membrane, whereas non-A, non-B intercalated cells express this H+-pump on the apical plasma membrane. Principal cells express ENaC on the apical plasma membrane, which provides the driving force for K+ secretion and also augments the secretion of H+.

Type B intercalated cells express Na+-independent, electroneutral, Cl−/HCO3− exchange on the apical plasma membrane, which is mediated primarily by pendrin (2, 70). Within the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, i.e., DCT, CNT, and CCD, pendrin is found in the apical regions of type B and non-A, non-B intercalated cells (Fig. 3) (38, 70, 102). Pendrin gene ablation markedly reduces but does not eliminate apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in mouse CCD (2). Since pendrin-positive intercalated cells do not express AE1 and do not express the H+-ATPase in the apical regions, pendrin has been used as a marker of type B and non-A, non-B intercalated cells (38, 70, 102). In type B cells, apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange acts in series with the H+-ATPase on the basolateral plasma membrane (1, 18, 37, 84, 91) to mediate secretion of OH− equivalents into the luminal fluid. When these B-cell transporters are upregulated, HCO3− secretion increases (70, 79), which helps correct a metabolic alkalosis.

The functional distinction of intercalated cell subtypes is not predicted fully by H+-ATPase subcellular distribution, however. Type A cells are identified by H+-ATPase labeling on the apical plasma membrane and in subapical vesicles and AE1 labeling on the basolateral membrane. Cells with these properties account for 50–64% of intercalated cells in the mouse CCD (37, 91). Type B cells of mouse CCD are identified by with basolateral or diffuse H+-ATPase labeling and apical pendrin labeling and account for the other 46–50% of intercalated cells (37, 38, 70, 91, 102). Functional data taken from mouse and rabbit CCDs perfused in vitro have shown that apical Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchange is observed in 90% of intercalated cells, while only 4–14% of intercalated cells lack Na+-independent apical anion exchange (type A) (17, 19). Since the abundance of intercalated cells with apical Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity greatly exceeds the abundance of intercalated cells that express pendrin and since pendrin gene ablation reduces but does not eliminate apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in intercalated cells, Na+-independent apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange occurs through pendrin-independent pathways. One such candidate is Slc4a11, which is expressed in the apical regions of type A cells and acts as an electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchanger or a Cl− channel (Fig. 3) (117).

Transepithelial Transport of Cl− Through Electrogenic and Electroneutral Pathways

In the CCD, transepithelial transport of Cl− occurs primarily across intercalated cells rather than across principal cells (76). However, intercalated cells, unlike principal cells, do not have a significant transcellular conductance (106). Instead, Stoner et al. (87) noted 4 decades ago that most Cl− flux in the CCD is electrically silent. Further work by Schuster and Stokes (80) demonstrated that Cl− absorption occurs through Cl−/Cl− or Cl−/HCO3− exchange. Weiner and Hamm (107), Emmons and Kurtz (19), and Star et al. (84) demonstrated electroneutral, Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchange across the apical plasma membrane of intercalated cells. Thus under most experimental conditions, most Cl− absorption in the CCD occurs through electroneutral anion exchange, rather than through a conductive pathway (87). Electroneutral Cl−/HCO3− exchange is a tightly controlled process that is upregulated by cAMP (78), aldosterone (24), angiotensin II (108), carbonic anhydrase (54), and CO2 (54).

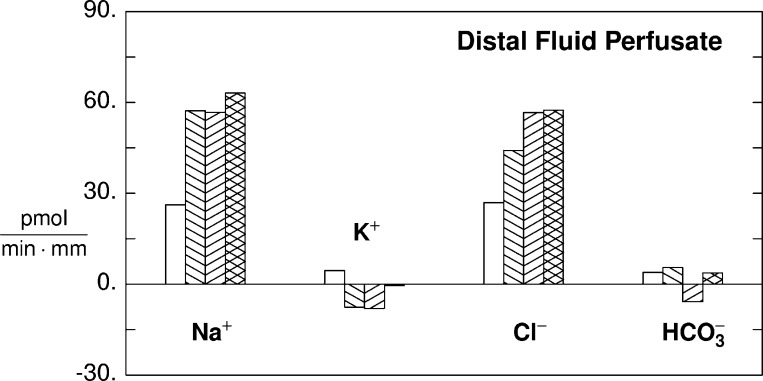

While Cl− absorbed through electroneutral, Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchange occurs independent of electrical potential, there is an electrical impact of coordinated intercalated cell transport. In non-A, non-B cells, the apical membrane expresses both the H+-ATPase and pendrin-mediated Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchange, which leads to the secretion of H+ and HCO3− in tandem by this cell type. H+ and HCO3− are also secreted in tandem vis-à-vis the apical H+-ATPase in type A cells and through apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in type B intercalated cells, acting in parallel. In both of these models, neutral CO2 is generated, which is absorbed with Cl−. Thus intercalated and principal cells act together to mediate the absorption of NaCl with little change in net secretion of H+ or OH− equivalents. This scheme predicts that during volume depletion, transporters within type A and type B cells or within non-A, non-B cells are upregulated, which greatly increases NaCl absorption without significantly changing net H+ flux. This is illustrated quantitatively in Fig. 4, which displays calculations using the CCD model of Weinstein (110). In Fig. 4, CCD transport rates for Na+, K+, Cl−, and HCO3− are displayed for a 2-mm tubule segment in which a late distal fluid enters at 3 nl/min. When only principal cell transport is scaled up, Na+ transport increases and K+ flux changes from net absorption to net secretion. Cl− absorption also increased due to increased paracellular flux, driven by the lumen-negative transepithelial voltage. As type B-cell function increases further, Cl− absorption continues to rise but with the appearance of net HCO3− secretion. With increased type A-cell function, H+ secretion increases, which limits the rise in luminal HCO3− concentration that follows Cl−/HCO3− exchange-mediated HCO3− secretion. Moreover, H+ secretion should shunt the current generated by ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption, thereby augmenting Na+ absorption. Finally, K+ absorbed by the luminal H-K-ATPase should attenuate the net K+ secretion generated by the lumen-negative voltage (81, 82).

Fig. 4.

Predicted electrolyte transport using a model of rat CCD (105). All calculations assume a 2-mm tubule segment perfused at a rate of 3 nl/min. The bath is a Ringer solution (Na+ = 140, K+ = 5.0, Cl− = 114, HCO3− = 25, total phosphate = 3.9, total ammonia = 1.0, urea = 5.0, pH = 7.32). The perfusate is typical of late distal tubule fluid (Na+ = 70, K+ = 24, Cl = 71, HCO3− = 14, total phosphate = 7.8, total ammonia = 4.0, urea = 60, pH = 7.07). Four simulations are displayed, in which all transporters (luminal and peritubular) of the designated cell may be scaled by a common factor, to scale the transcellular ion fluxes: baseline (clear bar); all PC transporters scaled by a factor of 2 (\); PC scaled by a factor of 2 and beta-intercalated cell (IC) by 5 (/); and PC scaled by a factor of 2, beta-IC by 5, and alpha-IC by 4. The bars show transport of Na+, K+, Cl−, and HCO3−. Positive values indicate absorption, whereas negative values indicate secretion. With PC scaling alone, Na+ absorption doubles, and K+ flux changes from net absorption to net secretion. The increase in Cl− absorption is paracellular, driven by the lumen-negative transepithelial voltage. When beta-IC are also scaled, Cl− reabsorption increases further, and there is net HCO3− secretion. Finally, with alpha-IC scaling, net HCO3− reabsorption is restored to baseline; the more positive lumen, provided by H+ secretion, yields a small increase in Na+ reabsorption; and net K+ flux is close to zero (scaling of alpha-IC includes both H+-ATPase and H-K-ATPase within the luminal membrane).

There is functional evidence that apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in B cells functions in parallel with the “gastric” H-K-ATPase, HKα1, encoded by ATP4α, which localizes to intercalated cells within the rat and rabbit CCD (46, 116). In this model, apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange-mediated Cl− absorption and HCO3− secretion functions in tandem with H-K-ATPase-mediated K+ absorption and H+ secretion (50, 118). When these two transport processes act in tandem, net absorption of KCl is expected without a significant change in the secretion of H+ equivalents (53, 83, 118). However, since no change in renal K+ handling or acid-base balance has been observed following genetic ablation of either the α1 (gastric)- or the α2 (colonic)-isoforms of the H-K-ATPase (50), the significance of the H-K-ATPase isoforms in the renal excretion of K+ and net acid remains to be determined (50).

Cl− absorption is mediated, in part, through an electroneutral, thiazide-sensitive mechanism that is distinct from the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter expressed in the DCT (48). In mouse and rat CCD, application of thiazides to the perfusate reduces the absorption of Na+, Cl−, and HCO3−, without changing transepithelial voltage or K+ flux (48, 92). Therefore, thiazide-sensitive Cl− absorption occurs through electroneutral, Na+-dependent Cl−/HCO3− exchange (48, 92). While the gene(s) that encode this exchange process are not fully defined, Na+-dependent Cl−/HCO3− exchange encoded by Slc4a8 participates in this transport pathway (48, 92) and may operate in parallel with other electroneutral Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, such as pendrin, to mediate this thiazide-sensitive electroneutral NaCl absorption (48). Whether Slc4a8 localizes to principal and/or intercalated cells is unresolved, although functional data suggest that this exchanger localizes to type B intercalated cells (48). How Slc4a8 and pendrin might function in tandem is shown in Fig. 3 (13). In this model (13), Slc4a8 mediates NaHCO3 absorption and Cl− secretion across the apical membrane of type B intercalated cells. The secreted Cl− is absorbed by pendrin-mediated apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange and therefore recycled. In turn, pendrin-mediated HCO3− secretion is absorbed by Slc4a8. When two pendrin (Slc26a4) molecules and one Slc4a8 molecules act in tandem, NaCl is absorbed without an appreciable change in HCO3− flux. However, this stoichiometry has not yet been proven experimentally.

The relative contribution of the thiazide-sensitive component of Cl− absorption to total transepithelial Cl− absorption varies widely depending on the treatment model employed (48, 62, 92). For example, in the CCD of salt-deprived mice, Cl− absorption is thiazide-sensitive but amiloride-insensitive (48). However, following the administration of aldosterone and a NaCl-rich diet, Cl− absorption is sensitive to amiloride analogs (benzamil), while a thiazide-sensitive component of Cl− absorption is undetectable (62). Inhibiting the epithelial sodium channel with drugs such as amiloride or benzamil reduces Cl− absorption through a mechanism separate from that of thiazide-sensitive Cl− absorption that involves stimulating conductive Cl− secretion, rather than directly inhibiting Cl− absorption (62). This Cl− secretory pathway likely localizes to type A intercalated cells, since this cell type mediates Cl− secretion in the outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD) and since conductive Cl− secretion is dependent on NKCC1, which localizes to type A intercalated cells in mouse CCD and OMCD (27, 62, 101). In this model, during ENaC blockade Cl− is taken up across the basolateral membrane of type A intercalated cells in the CCD through the Na+-K+−2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1) and is then secreted into the luminal fluid through a conductive pathway (Fig. 3) (62). Whether this conductive Cl− secretion occurs through a channel or an electrogenic transporter remains unresolved.

Following Cl− absorption, Cl− may exit across the basolateral membrane of type A or B cells through an exchanger or a Cl− channel, such as ClC-K2. ClC-K2 is found in the basolateral regions of the thick ascending limb, the DCT, principal, and intercalated cells of the CNT and in type A and B intercalated cells of the collecting duct (Fig. 3) (33, 43, 44). Since Cl− channel activity is higher in intercalated cells than in principal cells of the CCD (58) and since the biophysical properties of this intercalated cell Cl− channel are more consistent with ClC-K2 than other classes of Cl− channels (58), ClC-K2 is a candidate for the Cl− channel activity observed on the basolateral plasma membrane of intercalated cells. Because activation mutations of ClC-K2 lead to hypertension (32), this transporter likely fosters Cl− absorption. While this Cl− channel may participate in the process of Cl− absorption within the CCD, it may instead participate in Cl− recycling across the basolateral membrane, which promotes the flux of another ion (33).

Electroneutral, Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchange is observed across the basolateral membrane in the majority of intercalated cells and probably mediates Cl− uptake. Of these, the best characterized is AE1, which localizes to the basolateral membrane of type A intercalated cells (Fig. 3) (1). In type A cells, the apical H+-ATPase appears to function in series with AE1 to mediate the secretion of net H+ equivalents. The source of H+ for apical H+ secretion by type A intercalated cells is CO2 (100). Within type A intercalated cells, carbon dioxide combines with H2O to generate H+ and HCO3−. H+ is secreted across the apical membrane, which acidifies the luminal fluid, whereas HCO3− exits the cell across the basolateral membrane through Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, such as AE1. With elimination of AE1, an impaired ability of type A cells to secrete H+ equivalents is predicted. While the effect of AE1 gene ablation on total CO2 flux has not been tested directly in mouse CCD, it is well established that AE1 gene ablation in mice and in people results in a severe metabolic acidosis (85).

Implication of Intercalated Cell Cl− Transport in the Maintenance of Extracellular Fluid Volume

In humans, the clinical consequences of pendrin gene disruption were first described in 1896. In this landmark paper, Dr. Vaughn Pendrin described a family in which 2 of the 10 children suffered from deafness and goiter (Pendred Syndrome) (65). The gene responsible for Pendred Syndrome was reported by Everett et al. 101 yr later (20). Pendred Syndrome is now known to be an autosomal recessive disorder associated with more than 47 disease-producing allele variants of Slc26a4 (8). While pendrin has long been known to be critical in hearing and thyroid function, more recent evidence points to an important role of this transporter in the renal regulation of NaCl balance. Moreover, patients with Pendred Syndrome may be protected from the development of hypertension (51).

While Na+ intake is important in the pathogenesis of hypertension, in human and in rodent models of hypertension, blood pressure is also modulated by Cl− intake (47). Extracellular volume expansion likely occurs in part from increased intake of Cl− coupled with upregulation of renal transporters that mediate Cl− absorption. Studies of transgenic mice have shown that electroneutral, Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, such as pendrin modulate blood pressure. Following NaCl restriction, where renin and aldosterone release are appropriately stimulated, pendrin null mice have enhanced excretion of Na+ and Cl− and lower blood pressure relative to wild-type mice (39, 99, 103). Blood pressure is lower in pendrin null relative to wild-type mice following other treatment models, such as during selective dietary Cl− restriction (99). Therefore, the lower blood pressure observed with pendrin gene ablation (39, 99, 103) occurs, at least in part, from the impaired ability of the pendrin null mice to fully conserve urinary Na+ and Cl−.

Aldosterone increases blood pressure, in part, by increasing the abundance and function of NaCl transporters such as ENaC (12) and pendrin (97) in tandem. In rats and rabbits, Cl− absorption and HCO3− secretion increase markedly in CCDs following aldosterone treatment in vivo (24, 29, 42, 84). This aldosterone-induced increase in Cl−/HCO3− exchange occurs by upregulating apical, electroneutral, Na+-independent Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, such as pendrin (97). While B-cell apical plasma membrane pendrin immunoreactivity is low under basal conditions (97, 102), aldosterone increases apical membrane pendrin abundance sixfold, primarily through subcellular redistribution (97), which markedly increases pendrin-mediated transport (62). The Cl− absorption and HCO3− secretion observed in the CCD of aldosterone-treated mice is completely dependent on pendrin, since HCO3− secretion and Cl− absorption are not observed in aldosterone-treated pendrin null mice (70, 103). In the absence of pendrin (pendrin null mice), a blunted hypertensive response to aldosterone is observed (97). Thus pendrin participates in the pressor response to aldosterone, likely by enhancing renal Cl− absorption.

Interaction Between Intercalated Cells and Principal Cells Following Aldosterone Administration

The chloriuresis observed in pendrin null mice occurs, at least in part, from the absence of pendrin-mediated Cl− absorption (99, 103). However, since pendrin does not transport Na+, the mechanism of the natriuresis observed in pendrin null mice was not obvious (39). We asked if the pendrin null mice have a reduced ability to conserve urinary Na+, due to reduced renal Na+ transporter expression. Thus renal Na+ transporter abundance was quantified in kidneys from wild-type and pendrin null mice following treatment models in which circulating aldosterone concentration is either low or high (39). The abundance of NHE3, α1-Na-K-ATPase, NKCC2, ENaC, and NCC is similar in kidneys from wild-type and Slc26a4 null mice when consuming a balanced NaCl-replete diet (39). However, under conditions that increase serum aldosterone concentration, such as with NaCl restriction or an aldosterone infusion, β- and γENaC subunit abundance is reduced in kidneys from Slc26a4(−/−) mice (39, 60). In particular, we observed a blunted increment in the abundance of the mature, 70-kDa fragment of γENaC in kidneys from Slc26a4 null mice following aldosterone administration (39). Changes in ENaC abundance observed in pendrin null mice appear limited to the kidney and cannot be explained by altered endocrine function (39).

To assess ENaC function, transepithelial voltage, VT, was measured in CCDs perfused in vitro before and after the application of the ENaC inhibitor to the luminal fluid (39). Mice were given furosemide for 5 days to upregulate pendrin and ENaC (36, 56, 59, 67). In CCDs from furosemide-treated wild-type mice, a lumen-negative VT was observed, which was obliterated with the application of the ENaC inhibitor benzamil to the luminal fluid. However, in CCDs from furosemide-treated pendrin null mice, VT was very low and unchanged with benzamil (39). These data are consistent with robust ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption in CCDs from wild-type mice and low ENaC-mediated transport in CCDs from pendrin null mice. Thus both ENaC abundance and function are markedly reduced in kidneys from pendrin null mice. This reduction in ENaC function contributes to the lower blood pressure observed in these mutant mice.

In human and rodent kidney, pendrin and ENaC both localize to the aldosterone-sensitive region of the nephron, i.e., the terminal portion of the DCT (DCT2), CNT, the initial collecting tubule, and CCD (28, 38, 70, 102). However, these transporters localize to different cell types within these segments. Pendrin localizes to the apical regions of type B and non-A, non-B intercalated cells (38, 70, 102), whereas ENaC is expressed in the apical regions of principal cells (28) (Fig. 3). Since ENaC and pendrin localize to different cell types, this communication cannot occur through a direct protein-protein interaction.

Further studies explored how pendrin changes ENaC abundance and function (60). While Slc26a4/SLC26A4 expression is high in both rodent and human kidney, in both human and in mouse models of Pendred Syndrome, no acid-base or fluid and electrolyte abnormalities are seen under basal conditions (70, 97, 103). However, with aldosterone or NaHCO3 administration, which upregulates pendrin abundance in wild-type mice, a more severe metabolic alkalosis is observed in pendrin null mice probably due to their reduced capacity to secrete HCO3− (97, 99, 103). While the renal phenotype has been well studied in mouse models of Pendred Syndrome, the effect of pendrin gene ablation on acid-base and fluid and electrolyte balance in people has had limited study. However, Pela et al. (64) observed a person with Pendred Syndrome who developed a severe metabolic alkalosis following treatment with thiazide diuretics. This case report is consistent with the alkalosis observed in rodent models of Pendred Syndrome.

Since pendrin mediates HCO3− secretion and since ENaC may be pH sensitive (60), we hypothesized that pendrin stimulates ENaC by raising luminal HCO3− concentration (60). To test this hypothesis, pendrin null and wild-type mice were given NaHCO3 and aldosterone to stimulate pendrin-mediated HCO3− secretion (42). In other experiments, mice were given this treatment plus a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (acetazolamide) to increase luminal HCO3− concentration by stimulating distal HCO3− delivery from upstream segments, while inhibiting pendrin-mediated apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange (54). Thus luminal HCO3− concentration in the CCD and CNT increased through a pendrin-independent mechanism. We observed a more severe metabolic alkalosis and lower renal ENaC subunit abundance and function in pendrin null relative to wild-type mice following treatment with aldosterone and NaHCO3 (60). However, when acetazolamide was added to the protocol, acid-base balance as well as ENaC subunit abundance and function were similar in kidneys from wild-type and pendrin null mice (60). Thus stimulating distal HCO3− delivery from upstream segments rescues pendrin null mice from the expected fall in ENaC abundance and function. To determine if HCO3− has a direct effect on ENaC abundance and function, further experiments used cultured mouse principal cells (mpkCCD; Ref. 60). We observed that increasing HCO3−concentration on the apical side of the monolayer augmented ENaC abundance and function. Thus pendrin modulates ENaC, at least in part, by raising luminal HCO3− concentration. Whether this occurs from a direct effect of HCO3− or from the pH change that occurs when HCO3− concentration is varied remains to be determined. Moreover, there are likely additional mechanisms whereby pendrin modulates ENaC abundance and function. For example, ENaC may be regulated by ATP released by intercalated cells, which is somehow coupled to pendrin function (13).

Regulation of Intercalated Cell Transporters by Angiotensin II

Angiotensin II modulates blood pressure (98), in part, by increasing renal NaCl absorption in the collecting duct through short- and long-term effects (5, 6, 59, 66). Early studies employed micropuncture to examine the impact of luminal angiotensin II on distal transport. Angiotensin increases Na+ and Cl− absorption in both early and late segments (i.e., the DCT and CNT; Ref. 104) and stimulates HCO3− absorption in the early, but not in the late segment (3, 49, 104). However, rather than stimulating K+ secretion, angiotensin actually reduces K+ transport in the late segment (104).

Subsequent studies examined the molecular pathway(s) by which angiotensin II increases distal NaCl absorption. Angiotensin II increases α ENaC abundance in vivo through an AT1a receptor-dependent process (5, 6). In the CCD, angiotensin II also stimulates ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption in vitro in a dose-dependent fashion (66). Since angiotensin II stimulates ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption, further experiments by our laboratory asked if angiotensin II also increases Cl− absorption in the CCD (59). While CCDs from wild-type mice do not absorb Cl− under basal conditions, when pendrin abundance is upregulated with furosemide administration, Cl− absorption is observed (59), which doubles with angiotensin II application in vitro (59). However, in CCDs from furosemide-treated pendrin null mice, Cl− absorption was not observed either in the presence or the absence of angiotensin II. Therefore, in CCDs perfused in vitro, angiotensin II increases Cl− uptake in wild-type mice through a pendrin-dependent mechanism.

Further experiments explored how angiotensin II stimulates pendrin-dependent Cl− absorption in mouse CCD. We reasoned that if angiotensin II increases the lumen-negative transepithelial voltage (VT) it should magnify the driving force for paracellular Cl− absorption. However, while Cl− absorption increased with angiotensin II application, transepithelial voltage, VT, was unchanged (59). Therefore, it is unlikely that angiotensin II stimulates Cl− absorption by increasing paracellular Cl− absorption (59).

Angiotensin II might increase pendrin-dependent transepithelial transport through increased apical plasma membrane pendrin abundance through covalent modification of pendrin or by creating a more favorable driving force for pendrin-mediated transport. However, since angiotensin II did not increase the abundance of pendrin on the apical plasma membrane in B cells (63), it does not increase pendrin-dependent Cl− absorption in vitro through changes in pendrin subcellular distribution. Since angiotensin II might stimulate Cl− uptake by changing the driving force for pendrin-mediated HCO3−/Cl− exchange, further studies explored whether angiotensin II increases the activity and the abundance of the apical (A cell) or the basolateral (B cell) H+-ATPase (63). Because angiotensin did not change B-cell basolateral plasma membrane H+-ATPase abundance, this hormone does not stimulate Cl− absorption by changing ion gradients through increased basolateral plasma membrane H+-ATPase abundance. However, angiotensin II might increase Cl− absorption through covalent modification of the B-cell H+-ATPase.

Angiotensin II applied in vitro upregulates A-cell apical plasma membrane H+-ATPase expression in both mouse CCD and OMCD (63, 69). In type A cells, angiotensin II application in vitro increases apical plasma membrane H+-ATPase expression nearly threefold through subcellular redistribution and changed total CO2 flux from net secretion to net absorption (63), consistent with increased H+ secretion. Since inhibiting the apical H+-ATPase does not change Cl− flux in CCDs from aldosterone-treated mice (61), stimulating apical H+ secretion with angiotensin II application probably does not markedly change pendrin-mediated Cl− absorption. Angiotensin II application may instead covalently modify pendrin, which stimulates anion exchange. Alternatively, this peptide hormone may instead facilitate Cl− exit or net H+ exit across the basolateral plasma membrane through subcellular redistribution or through covalent modification of a basolateral membrane H+, OH−, or Cl− transporter, which reduces intracellular Cl− or increases intracellular HCO3− concentration, thereby providing a more favorable driving force for apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange.

Interplay of Angiotensin and Aldosterone in the Cortical Distal Nephron

As discussed above, angiotensin acts in the CNT and CCD to enhance transport in principal and in type A and B intercalated cells. These two intercalated cell subtypes act in tandem to generate net electrogenic Cl− absorption. By promoting the absorption of an anion, the lumen negative electrical potential should fall, thereby decreasing K+ secretion. Increased ENaC activity augments the lumen-negative voltage, which blunts the fall in voltage expected with electrogenic anion absorption.

Application of either aldosterone or angiotensin II increases ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption, which increases the lumen-negative voltage, thereby stimulating K+ secretion. The relationship between K+ secretion and NaCl transport was recently addressed (115). In the DCT in vivo, NaCl restriction increases thiazide-sensitive NaCl absorption by upregulating angiotensin II, which stimulates the NaCl cotransporter (NCC) of the DCT (15). Angiotensin II increases apical plasma membrane NCC abundance in the DCT through subcellular redistribution (72), which activates NCC transport activity (71, 95), thereby increasing NaCl absorption in this segment (104). However, activating NaCl absorption in the DCT reduces Na+ delivery to the CNT, which reduces ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption. Therefore, K+ secretion declines due to the fall in ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption and the fall in CNT volume flow. However, the distal nephron model predicts that with increased DCT NaCl absorption, K+ secretion can be preserved by concomitant activation of principal cell transporters (115). Thus a picture emerges in which ENaC and pendrin are upregulated by angiotensin II and aldosterone in a coordinate manner, acting to restore extracellular volume while preserving K+ excretion. In this scheme, there may be communication from the type B intercalated cell to the principal cell through pendrin-mediated HCO3− secretion. Whether dysfunction of this transport configuration can also mediate the volume-dependent component of essential hypertension remains to be determined.

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

As mentioned above, how diuretics such as amiloride and thiazides reduce Cl− absorption in the rodent CCD is not fully explained. While amiloride has been thought to reduce Cl− absorption by eliminating the lumen-negative transepithelial voltage, which provides the driving force for paracellular Cl− absorption, this has never been directly tested and other mechanisms are possible. For example, by eliminating the lumen-negative voltage, the driving force for Cl− secretion mediated by an apical plasma membrane Cl− channel is greatly increased. Therefore, amiloride analogs may reduce Cl− absorption by stimulating Cl− channel-mediated Cl− secretion. Thiazide analogs also reduce Cl− absorption, at least in part, by inhibiting the Na+-dependent Cl−/HCO3− exchanger Slc4a8. However, whether thiazides inhibit Slc4a8 alone or inhibits a transporter complex is unknown.

Pendrin-mediated apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange is the best understood mechanism of Cl− absorption in the rodent CCD. Pendrin is highly regulated by aldosterone through changes in subcellular distribution. However, how aldosterone modulates the subcellular distribution of pendrin is unknown. Potential interaction with ubiquitin ligases may regulate this exchanger's distribution and function.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-46493 (to S. M. Wall) and DK-29857 (to A. M. Weinstein).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.M.W. and A.M.W. prepared figures; S.M.W. and A.M.W. drafted manuscript; S.M.W. and A.M.W. edited and revised manuscript; S.M.W. and A.M.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alper SL, Natale J, Gluck S, Lodish HF, Brown D. Subtypes of intercalated cells in rat kidney collecting duct defined by antibodies against erythroid band 3 and renal vacuolar H+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 5429–5433, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amlal H, Petrovic S, Xu J, Wang Z, Sun X, Barone S, Soleimani M. Deletion of the anion exchanger Slc26a4 (pendrin) decreases the apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger activity and impairs bicarbonate secretion in the kidney collecting duct. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C33–C41, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barreto-Chaves ML, Mello-Aires M. Effect of luminal angiotensin II and ANP on early and late cortical distal tubule HCO3− reabsorption. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F977–F984, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bastani B, Purcell H, Hemken P, Trigg D, Gluck S. Expression and distribution of renal vacuolar proton-translocating adenosine triphosphatase in response to chronic acid and alkali loads in the rat. J Clin Invest 88: 126–136, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beutler KT, Masilamani S, Turban S, Nielsen J, Brooks HL, Ageloff S, Fenton RA, Packer RK, Knepper MA. Long-term regulation of ENaC expression in kidney by angiotensin II. Hypertension 41: 1143–1150, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks HL, Allred AJ, Beutler KT, Coffman TM, Knepper MA. Targeted proteomic profiling of renal Na+ transporter and channel abundances in angiotensin II type 1a receptor knockout mice. Hypertension 39: 470–473, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown D, Hirsch S, Gluck S. Localization of a proton-pumping ATPase in rat kidney. J Clin Invest 82: 2114–2126, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Campbell C, Cucci RA, Prasad S, Green GE, Edeal JB, Galer CE, Karniski LP, Sheffield VC, Smith RJ. Pendred Syndrome, DFNB4, and Pds/Slc26a4 identification of eight novel mutations and possible genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Mutat 17: 403–411, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen L, Williams SK, Schafer JA. Differences in synergistic actions of vasopressin and deoxycorticosterone in rat and rabbit CCD. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F147–F156, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costanzo LS. Comparison of calcium and sodium transport in early and late rat distal tubules: effect of amiloride. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 246: F937–F945, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Costanzo LS, Windhager EE. Calcium and sodium transport by the distal convoluted tubule of the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 235: F492–F506, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eaton DC, Malik B, Saxena NC, Al-Khalili OK, Yue G. Mechanisms of aldosterone's action on epithelial Na+ transport. J Membr Biol 184: 313–319, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eladari D, Chambrey R, Peti-Peterdi J. A new look at electrolyte transport in the distal tubule. Annu Rev Physiol 74: 325–349, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elalouf JM, Roinel N, deRouffignac C. Effects of antidiuretic hormone on electrolyte reabsorption and secretion in distal tubules of rat kidney. Pflügers Arch 401: 167–173, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellison DH, Velazquez H, Wright FS. Adaptation of the distal convoluted tubule of the rat. Structural and functional effects of dietary salt intake and chronic diuretic infusion. J Clin Invest 83: 113–126, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellison DH, Velazquez H, Wright FS. Thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotranport in early distal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F546–F554, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emmons C. Functional characterization of anion exchange in mouse cortical collecting duct (CCD) intercalated cells (ICs). J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 5A, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Emmons C. New subtypes of rabbit CCD intercalated cells as functionally defined by anion exchange and H+-ATPase activity. J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 838, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emmons C, Kurtz I. Functional characterization of three intercalated cell subtypes in the rabbit outer cortical collecting duct. J Clin Invest 93: 417–423, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Everett LA, Glaser B, Beck JC, Idol JR, Buchs A, Heyman M, Adawi F, Hazani E, Nassir E, Baxevanis AD, Sheffield VC, Green ED. Pendred syndrome is caused by mutations in a putative sulphate transporter gene (PDS). Nat Genet 17: 411–422, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fejes-Toth G, Chen WR, Rusvai E, Moser T, Naray-Fejes-Toth A. Differential expression of AE1 in renal HCO3−-secreting and -reabsorbing intercalated cells. J Biol Chem 269: 16717–26721, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Field MJ, Stanton BA, Giebisch GH. Influence of ADH on renal potassium handling: a micropuncture and microperfusion study. Kidney Int 25: 502–511, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gamba G. Role of WNK kinases in regulating tubular salt and potassium transport and the development of hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F245–F252, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia-Austt J, Good DW, Burg MB, Knepper MA. Deoxycorticosterone-stimulated bicarbonate secretion in rabbit cortical collecting duct: effects of luminal chloride removal and in vivo acid loading. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 249: F205–F212, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garty H, Palmer LG. Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure, and regulation. Physiol Rev 77: 359–395, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gifford JD, Galla JH, Luke RG, Rick R. Ion concentrations in the rat CCD: differences between cell types and effect of alkalosis. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F778–F782, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ginns SM, Knepper MA, Ecelbarger CA, Terris J, He X, Coleman RA, Wade JB. Immunolocalization of the secretory isoform of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter in rat renal intercalated cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2533–2542, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hager H, Kwon TH, Vinnikova AK, Masilamani S, Brooks HL, Frokiaer J, Knepper MA, Nielsen S. Immunocytochemical and immunoelectron microscopic localization of a-, b- and g-ENaC in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F1093–F1106, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hanley MJ, Kokko JP. Study of chloride transport across the rabbit cortical collecting tubule. J Clin Invest 62: 39–44, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hou J, Rajagopal M, Yu AS. Claudins and the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 479–501, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hou J, Renigunta A, Yang J, Waldegger S. Claudin-4 forms paracellular chloride channel in the kidney and requires claudin-8 for tight junction localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18010–18015, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jeck N, Waldegger S, Lampert A, Boehmer C, Waldegger P, Lang PA, Wissinger B, Friedrich B, Risler T, Moehle R, Lang UE, Zill P, Bondy B, Schaeffeler E, Asante-Poku S, Seyberth H, Schwab M, Lang F. Activating mutation of the renal epithelial chloride channel ClC-Kb predisposing to hypertension. Hypertension 43: 1175–1181, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jentsch TJ. Chloride transport in the kidney: lessons from human disease and knockout mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1549–1561, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kahle KT, MacGregor GG, Wilson FH, Van Hoek AN, Brown D, Ardito T, Kashgarian M, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Boulpaep EL, Lifton RP. Paracellular Cl− permeability is regulated by WNK4 kinase: insight into normal physiology and hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14877–14882, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khuri RN, Wiederholt M, Strieder N, Giebisch G. Effects of graded solute diuresis on renal tubule sodium transport in the rat. Am J Physiol 228: 1262–1268, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ki YN, Oh YK, Han JS, Joo KW, Lee JS, Earm JH, Knepper MA, Kim GH. Upregulation of Na+ transporter abundances in response to chronic thiazide or loop diuretic treatment in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F133–F143, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim J, Kim YH, Cha JH, Tisher CC, Madsen KM. Intercalated cell subtypes in connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct of rat and mouse. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1–12, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim YH, Kwon TH, Frische S, Kim J, Tisher CC, Madsen KM, Nielsen S. Immunocytochemical localization of pendrin in intercalated cell subtypes in rat and mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F744–F754, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim YH, Pech V, Spencer KB, Beierwaltes WH, Everett LA, Green ED, Shin WK, Verlander JW, Sutliff RL, Wall SM. Reduced ENaC expression contributes to the lower blood pressure observed in pendrin null mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1314–F1324, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirk A, Campbell S, Bass P, Mason J, Collins J. Differential expression of claudin tight junction proteins in the human cortical nephron. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2107–2119, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Knepper MA, Danielson RA, Saidel GM, Post RS. Quantitative analysis of renal medullary anatomy in rats and rabbits. Kidney Int 12: 313–323, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Knepper MA, Good DW, Burg MB. Ammonia and bicarbonate transport by rat cortical collecting ducts perfused in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 249: F870–F877, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kobayashi K, Uchida S, Mizutani S, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Intrarenal and cellular localization of CLC-K2 protein in the mouse kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1327–1334, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kobayashi K, Uchida S, Okamura HO, Marumo F, Sasaki S. Human CLC-KB gene promoter drives the EGFP expression in the specific distal nephron segments and inner ear. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1992–1998, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koeppen BM, Biagi BA, Giebisch GH. Intracellular microelectrode characterization of the rabbit cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 244: F35–F47, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kraut JA, Helander KG, Helander HF, Iroezi ND, Marcus EA, Sachs G. Detection and localization of H+-K+-ATPase isoforms in human kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F763–F768, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kurtz TW, Hamoudi AA, Morris RC. “Salt-sensitive” essential hypertension in men. N Engl J Med 317: 1043–1048, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leviel F, Hubner CA, Houillier P, Morla L, El Moghrabi S, Brideau G, Hatim H, Parker MD, Kurth I, Kougioumtzes A, Sinning A, Pech V, Riemondy KA, Miller RL, Hummler E, Shull GE, Aronson PS, Doucet A, Wall SM, Chambrey R, Eladari D. Identification of a novel electroneutral Na+ reabsorption process in the distal nephron mediated by the Na+-dependent chloride-bicarbonate exchanger Slc4A8. J Clin Invest 120: 1627–1635, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levine DZ, Iacovitti M, Buckman S, Burns KD. Role of angiotensin II in dietary modulation of rat late distal tubule bicarbonate flux in vivo. J Clin Invest 97: 120–125, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lynch IJ, Rudin A, Xia SL, Stow LR, Shull GE, Weiner ID, Cain BD, Wingo CS. Impaired acid secretion in cortical collecting duct intercalated cells from H-K-ATPase-deficient mice: role of HKα isoforms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F621–F627, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Madeo AC, Manichaikul A, Pryor SP, Griffith AJ. Do mutations of the Pendred syndrome gene, SLC26A4, confer resistance to asthma and hypertension? J Med Genet 46: 405–406, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malnic G, Klose RM, Giebisch G. Micropuncture study of distal tubular potassium and sodium transport in rat nephron. Am J Physiol 211: 529–547, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meneton P, Schultheis PJ, Greeb J, Nieman ML, Liu LH, Clarke LL, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T. Increased sensitivity to K+ deprivation in colonic H,K-ATPase-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 101: 536–542, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Milton AE, Weiner ID. Regulation of B-type intercalated cell apical anion exchange activity by CO2/HCO3−. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F1086–F1094, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Muto S, Giebisch G, Sansom SC. Effects of adrenalectomy on CCD: evidence for differential response of two cell types. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F742–F752, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Na KY, Kim GH, Joo KW, Lee JW, Jang HR, Oh YK, Jeon US, Chae SW, Knepper MA, Han JS. Chronic furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide administration increases H+-ATPase B1 subunit abundance in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1701–F1709, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. O'Neil RG, Sansom SC. Electrophysiological properties of cellular and paracellular conductive pathways of the rabbit cortical collecting duct. J Membr Biol 82: 281–295, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Palmer LG, Frindt G. Cl− channels of distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1157–F1168, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pech V, Kim YH, Weinstein AM, Everett LA, Pham TD, Wall SM. Angiotensin II increases chloride absorption in the cortical collecting duct in mice through a pendrin-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F914–F920, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pech V, Pham TD, Hong S, Weinstein AM, Spencer KB, Duke BJ, Walp E, Kim YH, Sutliff RL, Bao HF, Eaton DC, Wall SM. Pendrin modulates ENaC function by changing luminal HCO3−. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1928–1941, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pech V, Thumova M, Dikalov S, Hummler E, Rossier BC, Harrison DG, Wall SM. Nitric oxide reduces Cl− absorption in the mouse cortical collecting duct through an ENaC-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F1390–F1397, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pech V, Thumova M, Kim YH, Agazatian D, Hummler E, Rossier BC, Weinstein AM, Nanami M, Wall SM. ENaC inhibition stimulates Cl− secretion in the mouse cortical collecting duct through an NKCC1-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F45–F55, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pech V, Zheng W, Pham TD, Verlander JW, Wall SM. Angiotensin II activates H+-ATPase in type A intercalated cells in mouse cortical collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 84–91, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pela I, Bigozzi M, Bianchi B. Profound hypokalemia and hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis during thiazide therapy in a child with Pendred Syndrome. Clin Nephrol 69: 450–453, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pendred V. Deaf-mutism and goitre. Lancet 2: 532, 1896 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Peti-Peterdi J, Warnock DG, Bell PD. Angiotensin II directly stimulates ENaC activity in the cortical collecting duct via AT1 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1131–1135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Quentin F, Chambrey R, Trinh-Trang-Tan MM, Fysekidis M, Cambillau M, Paillard M, Aronson PS, Eladari D. The Cl−/HCO3− exchanger pendrin in the rat kidney is regulated in response to chronic alterations in chloride balance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1179–F1188, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Reilly RF, Ellison DH. Mammalian distal tubule: physiology pathophysiology, and molecular anatomy. Physiol Rev 80: 277–313, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rothenberger F, Velic A, Stehberger PA, Kovacikova J, Wagner CA. Angiotensin II stimulates vacuolar H+-ATPase activity in renal acid-secretory intercalated cells rom the outer medullary collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2085–2093, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Royaux IE, Wall SM, Karniski LP, Everett LA, Suzuki K, Knepper MA, Green ED. Pendrin, encoded by the pendred syndrome gene, resides in the apical region of renal intercalated cells and mediates bicarbonate secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4221–4226, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. San-Cristobal P, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Richardson C, Ring AM, Vazquez N, Rafiqi FH, Chari D, Kahle KT, Leng Q, Bobadilla NA, Hebert SC, Alessi DR, Lifton RP, Gamba G. Angiotensin II signaling increases activity of the renal Na-Cl cotransporter through a WNK4-SPAK-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4384–4389, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sandberg MB, Riquier AD, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, McDonough AA, Maunsbach AB. Angiotensin II provokes acute trafficking of distal tubule NaCl cotransporter (NCC) to the apical membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F662–F669, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sansom SC, O'Neil RG. Effects of mineralocorticoids on transport properties of cortical collecting duct basolateral membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 251: F743–F757, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sansom SC, Weinman EJ, O'Neil RG. Microelectrode assessment of chloride-conductive properties of cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 247: F291–F302, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schafer JA, Troutman SL. cAMP mediates the increase in apical membrane Na conductance produced in rat CCD by vasopressin. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F823–F831, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schlatter E, Greger R, Schafer JA. Principal cells of cortical collecting ducts of the rat are not a route of transepithelial Cl− transport. Pflügers Arch 417: 317–323, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schlatter E, Schafer JA. Electrophysiological studies in principal cells of rat cortical collecting tubules. Pflügers Arch 409: 81–92, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schuster VL. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-stimulated anion transport in rabbit cortical collecting duct. J Clin Invest 78: 1621–1630, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schuster VL. Function and regulation of collecting duct intercalated cells. Annu Rev Physiol 55: 267–288, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Schuster VL, Stokes JB. Chloride transport by the cortical and outer medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F203–F212, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Silver RB, Choe H, Frindt G. Low-NaCl diet increases H-K-ATPase in intercalated cells from rat cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F94–F102, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Silver RB, Soleimani M. H+-K+-ATPases: regulation and role in pathophysiological states. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F799–F811, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Spicer Z, Miller ML, Andringa A, Riddle TM, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Shull GE. Stomachs of mice lacking the gastric H,K-ATPase a-subunit have achlorhydria, abnormal parietal cells, and ciliated metaplasia. J Biol Chem 275: 21555–21565, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Star RA, Burg MB, Knepper MA. Bicarbonate secretion and chloride absorption by rabbit cortical collecting ducts: role of chloride/bicarbonate exchange. J Clin Invest 76: 1123–1130, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Stehberger PA, Shmukler BE, Stuart-Tilley AK, Peters LL, Alper SL, Wagner CA. Distal renal tubular acidosis in mice lacking the AE1 (band 3) Cl/HCO3 exchanger (Slc4a1). J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1408–1418, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Stein JH, Osgood RW, Boonjarern S, Cox JW, Ferris TF. Segmental sodium reabsorption in rats with mild and severe volume depletion. Am J Physiol 227: 351–359, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Stoner LC, Burg MB, Orloff J. Ion transport in cortical collecting tubule; effect of amiloride. Am J Physiol 227: 453–459, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Strieter J, Stephenson JL, Giebisch GH, Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of the cortical collecting tubule of the rabbit. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F1063–F1075, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tatum R, Zhang Y, Lu Q, Kim K, Jeansonne BG, Chen YH. WNK4 phosphorylates ser206 of claudin-7 and promotes paracellular Cl− permeability. FEBS Lett 581: 3887–3891, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tatum R, Zhang Y, Salleng K, Lu Z, Lin JJ, Lu Q, Jeansonne BG, Ding L, Chen YH. Renal salt wasting and chronic dehydration in claudin-7-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F24–F34, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Teng-ummnuay P, Verlander JW, Yuan W, Tisher CC, Madsen KM. Identification of distinct subpopulations of intercalated cells in the mouse collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 260–274, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Terada Y, Knepper MA. Thiazide-sensitive NaCl absorption in rat cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F519–F528, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tomita K, Pisano JJ, Burg MB, Knepper MA. Effect of vasopressin and bradykinin on anion transport by the rat cortical collecting duct. J Clin Invest 77: 136–141, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tomita K, Pisano JJ, Knepper MA. Control of sodium and potassium transport in the cortical collecting duct of the rat. J Clin Invest 76: 132–136, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. van der Lubbe N, Lim CH, Fenton RA, Meima ME, Danser AH, Zietse R, Hoorn EJ. Angiotensin II induces phosphorylation of the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter independent of aldosterone. Kidney Int 79: 66–76, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Velazquez H, Ellison DH, Wright FS. Chloride-dependent potassium secretion in early and late renal distal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F555–F562, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Verlander JW, Hassell KA, Royaux IE, Glapion DM, Wang ME, Everett LA, Green ED, Wall SM. Deoxycorticosterone upregulates Pds (Slc26a4) in mouse kidney: role of pendrin in mineralocorticoid-induced hypertension. Hypertension 42: 356–362, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Verlander JW, Hong S, Pech V, Bailey JL, Agazatian D, Matthews SW, Coffman TM, Le T, Inagami T, Whitehill FM, Weiner ID, Farley DB, Kim YH, Wall SM. Angiotensin II acts through the angiotensin 1a receptor to upregulate pendrin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1314–F1325, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Verlander JW, Kim YH, Shin WK, Pham TD, Hassell KA, Beierwaltes WH, Green ED, Everett LA, Matthews SW, Wall SM. Dietary Cl− restriction upregulates pendrin expression within the apical plasma membrane of type B intercalated cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F833–F839, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wall SM, Fischer MP. Contribution of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1) to transepithelial transport of H+, NH4+, K+ and Na+ in rat outer medullary collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 827–835, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Wall SM, Fischer MP, Mehta P, Hassell KA, Park SJ. Contribution of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1) to Cl− secretion in rat outer medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F913–F921, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wall SM, Hassell KA, Royaux IE, Green ED, Chang JY, Shipley GL, Verlander JW. Localization of pendrin in mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F229–F241, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wall SM, Kim YH, Stanley L, Glapion DM, Everett LA, Green ED, Verlander JW. NaCl restriction upregulates renal Slc26a4 through subcellular redistribution: role in Cl− conservation. Hypertension 44: 1–6, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wang T, Giebisch G. Effects of angiotensin II on electrolyte transport in the early and late distal tubule in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F143–F149, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wang T, Malnic G, Giebisch G, Chan YL. Renal bicarbonate reabsorption in the rat. IV. Bicarbonate transport mechanisms in the early and late distal tubule. J Clin Invest 91: 2776–2784, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Warden DH, Schuster VL, Stokes JB. Characteristics of the paracellular pathway of rabbit cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F720–F727, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Weiner ID, Hamm LL. Use of fluorescent dye BCECF to measure intracellular pH in cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F957–F964, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Weiner ID, New AR, Milton AE, Tisher CC. Regulation of luminal alkaliniation and acidification in the cortical collecting duct by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 269: F730–F738, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of distal nephron acidification: diuretic effects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1353–F1364, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of rat cortical collecting duct: determinants of the transtubular potassium gradient. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F1072–F1092, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of rat distal convoluted tubule. I. Cotransporter function in early DCT. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F699–F720, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of rat distal convoluted tubule. II: Potassium secretion along the connecting segment. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F721–F741, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of the inner medullary collecting duct of the rat: acid/base transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F856–F867, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of the inner medullary collecting duct of the rat: pathways for Na and K transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F841–F855, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]