Abstract

Purpose

To perform a systematic review of adverse events associated with herb use in the pediatric population. Since many health care providers get their information about the safety of herbal medicine from case reports published in the medical literature, it is important to assess the quality of these case reports.

Methods

Electronic literature search included 7 databases and a manual search of retrieved articles from inception through 2010. We included case reports and case series that reported an adverse event associated with exposure to an herbal product by children under the age of 18 years old. Based on the International Society of Epidemiology's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication”, we assigned a guideline adherence score (0-17) to each case report.

Results

Ninety-six unique journal papers were identified and represented 128 cases. Of the 128 cases, 37% occurred in children under 2 years old, 38% between the ages of 2 – 8 years old, and 23 % between the ages 9-18 years old. In a few cases, the child used a product that was contaminated (5%) or adulterated (2%). Twenty-nine percent of cases were the result of an intentional ingestion while 36% were from an unintentional ingestion. Mean guideline adherence score was 12.5 (range 6 – 17).

Conclusions

There is considerable need for improvement in reporting adverse events in children following herb use. Without better quality reporting, adverse event reports cannot be interpreted reliably, and do not contribute in a meaningful way to guiding clinical recommendations.

Keywords: herbs, adverse events, pediatric, systematic review

Introduction

In 2007, an estimated 12% of U.S. children used complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), and biologically based therapies including herbs and dietary supplements were utilized by 5% of children.1 Little is known about pediatric herbal safety and how comprehensive herbal adverse events are in reporting details of the adverse event.

Definitions vary, but in general an adverse event (AE) is an unintended, undesired, or harmful effect associated with the use of a medication, intervention, or dietary supplement. In 2007, the Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act made it mandatory for all dietary supplement manufacturers or distributors to file serious adverse event reports to MedWatch. The Act defines a “serious adverse event” as one that results in (i) death, (ii) a life-threatening experience, (iii) in-patient hospitalization, (iv) a persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or (v) a congenital anomaly or birth defect; or requires, based on reasonable medical judgment, a medical or surgical intervention to prevent an outcome described above.2 In terms of models of herbal adverse event surveillance, there are many ways that adverse event reports (AERs) are collected in children including case reports in journals and media, post marketing surveillance, poison control centers, and other state and national government organizations (e.g. Medwatch). For example, the California Poison Control Centers reported that of 828 dietary supplement related adverse event exposure reports, more than half were among children. 3

AERs are also reported in the indexed medical literature. Case reports often come from clinicians who can comment on the presentation of the patient and the treatment plan that followed to address the event.4 Case reports are a common source of safety information for clinicians, but only if the information reported is sufficient in quality to allow for meaningful adjudication. It is important for case reports to include relevant information for clinicians to use when considering herbal recommendations to patients.

In this paper, we review case reports of pediatric adverse events (AEs) found in English language medical journals related to children's herb use and assess the quality of these AERs using a scale based on the International Society of Epidemiology's (ISE) “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication”. 4 While we cannot assess causality related to AEs, we can investigate whether case reports document the critical information about the AEs. We hypothesized that there would be a wide variety of adherence to the ISE's guidelines in the documentation of AERs described in case reports and that the overall documentation of the case reports would be poor. We also hypothesized that more complete documentation of case reports would occur in journals published after 2007 when the ISE's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication” were published compared to those before 2007.

Methods

Data Sources

We systematically searched seven databases: Medline, Embase, Toxline, DART, CINAHL, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Global Health from inception up through 2010 using MeSH terms such as herb, herbal medicine, phytotherapy, medicinal herb, plant extract, natural health products (NHPs), pediatrics, case reports, case series and safety (see Appendix 1 for all MeSH terms used in search strategy). Titles and abstracts of identified references were screened by two independent reviewers. Full publications of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further examination. We checked the references of each included article for additional reports.

Study Selection

We included peer-reviewed case reports/series published up through 2010 that described an AE occurring in newborns, infants, children, and youth from birth to age 18. Case reports were of medicinal herbal products taken by any route (e.g., oral, topical) by either a child or pregnant woman whose newborn was affected by the product. We did not include non-herb dietary supplements (e.g., glucosamine, CoQ10). Dissertations, abstracts, and non-English publications were also excluded. We also excluded randomized controlled trials as the purpose of this study was to analyze case reports and case series.

Data Extraction

The following data were independently double-extracted into a standardized database: patient demographics, medical history, details of case (e.g., how product exposure occurred, medical tests, treatment and outcome), and product details (e.g., name, contents, manufacturer). The main adverse event was characterized according to the primary symptom. If there were differences between reviewer categorization, we resolved it by discussion and consensus.

To assess case report guideline adherence, we developed a 17 point scale by adapting recommendations from the ISE's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication.” 4 These guidelines specifically take into account reporting herbal medicine case reports and the nuances unique to such reports such as the Latin binomial name of the herb and the generic or proprietary name of the herb. One point was allocated for reporting each of the following information: patient age, sex, description of the health condition being treated with the suspected herb, medical history related to the adverse event, physical exam, outcome of the patient (presence or absence of death, life-threatening circumstances, hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization or significant disability), the Latin binomial name of herb ingredient(s), the generic or proprietary name of herb, the plant part(s) of the herb, the type of preparation (e.g. crude herb or extract, pill/capsule, powder), manufacturer, dosage of the herb, duration of therapy, assessment of potential contribution of concomitant therapies, description of AE and its severity compared with established definitions and outcome of AE, and if the report included a discussion. The discussion must address causality, timing, and the presented report's consideration of previously published adverse events. To our knowledge, this scale has not been validated in previous studies.

Based on the ISE's guidelines, our adapted adherence scale represents the most basic information necessary for appropriate case presentation of an AE related to pediatric herb use. Interpretation of the scale was done on each case report.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics using SAS™ software (Version 9.1 Cary, NC: SAS Institute). To assess for significant factors associated with studies with higher adherence scores we used Poisson regression analysis. We categorized variables as follows: age (not documented, 0-23 months, 2-3 years, 4-8 years, 9-13 years, 14-18 years); race (not documented, Non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, African American, Asian, Other); gender; time of exposure (postnatal or prenatal exposure); main adverse event reported; route of administration (not specified, intentional oral ingestion, unintentional oral ingestion, intentional topical application, unintentional topical exposure, multiple modes); contaminated or adulterated products; lab analysis of herb; lab analysis of patient; exposure to heavy metals; disposition of patient (not documented, resolution of symptoms following hospitalization, resolution of symptoms with medications or outpatient therapy, death, disability, organ transplantation); location of case; year of publication (before 1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, and 2001-2010). Year of publication was further analyzed as cases published before 2007 and after 2007. Journals were categorized as adult or pediatric to assess if journals specializing on children would yield a higher adherence score.

Results

The searches identified 12,386 references. Initial screening of titles and abstracts removed 12,170 references. Full text of the remaining 216 references were obtained and assessed for inclusion. Figure 1 demonstrates our search strategy.

Figure 1. Flow of studies through review.

There were 96 unique papers representing 128 cases included in the analysis. (Appendix 1) Table 1 describes the characteristics of the included cases. Over one half of cases occurred in children 3 years of age or less. In 8% of the cases (n=10), exposure occurred through maternal transmission to the fetus. The most frequent herbs or herbal combinations mentioned were eucalyptus (n=12), camphor (n=10), fennel (n=6), jin bu huan (n=6), swanuri marili (n=6), kharchos suneli (n=6), tea tree (n=5), lavender (n=4), blue cohosh (n=3), buckthorn (n=3), liquorice (n=3), and garlic (n=3). While many cases reported multiple symptoms, there were a wide variety and severity of symptoms presented. (See Table 1) Most common (35% of the cases) symptoms were neurological adverse events (e.g., seizures). Fourteen percent of the cases (n=18) revealed gastrointestinal disturbances (e.g., nausea, vomiting).

Table 1. General Description of Adverse Events (N=128 Individual Cases).

| Category | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age | |

| Not documented | 1 (1) |

| 0-23 months | 48 (37) |

| 2-3 years | 25 (20) |

| 4-8 years | 23 (18) |

| 9-13 years | 14 (11) |

| 14-18 years | 17 (13) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Not documented | 80 (63) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 14 (11) |

| Hispanic | 12 (9) |

| African American | 2 (2) |

| Asian | 8 (6) |

| Other | 12 (9) |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (43) |

| Female | 55 (43) |

| Not documented | 18 (14) |

|

| |

| Time of Exposure | |

| Prenatal | 10 (8) |

| Postnatal | 118 (92) |

|

| |

| Main Adverse Event Reported* | |

| Neurological (seizures, CNS depression, lethargy) | 45 (35) |

| Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) | 18 (14) |

| Liver toxicity and jaundice | 14 (11) |

| Cardiovascular/Hematological (hypertension, blood toxicity) | 13 (10) |

| Dermatological (rash, burns) | 12 (9) |

| Respiratory (coughing, respiratory depression) | 9 (7) |

| Endocrine/Reproductive/Renal | 8 (6) |

| Cyanosis | 6 (5) |

| Neonatal withdrawal (drugs or alcohol) | 2 (2) |

| Anaphylactic shock | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Route of Administration | |

| Unintentional oral ingestion | 46 (36) |

| Intentional oral ingestion | 37 (29) |

| Topically applied | 22 (17) |

| Multiple modes | 2 (2) |

| Not specified | 2 (2) |

| Unintentional exposure to skin | 1 (1) |

| Contaminated or Adulterated Products | |

| Contaminated products reported in cases | 6 (5) |

| Adulterated products reported in cases | 2 (2) |

|

| |

| Documentation of testing herb in lab | 41 (32) |

|

| |

| Documentation of lab work on patient | 102 (80) |

|

| |

| Documentation of exposure to heavy metals | |

| Leads | 9 (7) |

| Arsenic | 2 (2) |

| None | 117 (91) |

|

| |

| Disposition | |

| Resolution of symptoms following hospitalization | 90 (70) |

| Resolution of symptoms with medications or outpatient therapy | 18 (14) |

| Death | 9 (7) |

| Disability | 7 (6) |

| Organ transplantation | 3 (2) |

| Not documented | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Location of Case | |

| United States | 40 (31) |

| Europe (continental) | 26 (20) |

| Asia | 21 (17) |

| Australia | 14 (11) |

| Great Britain | 9 (7) |

| India Canada | 6 (5) 5 (4) |

| Africa | 3 (2) |

| Central America | 3 (2) |

| Unknown | 1(1) |

This reflects the main clinical adverse event in case. Cases may have other symptoms reported.

Documentation of the plant part was evident in 41% of the cases and 94% documented the type of preparation of the herbal medicine. Thirty-two percent of the cases reported laboratory testing of the herb. Duration of herb use was documented in 92% of the cases but duration of herb use prior to the event was documented in only 41% of the cases. Dosage was documented in 67% of cases.

There was great diversity among route of exposure among the pediatric population discussed. Twenty-nine percent of cases were the result of an intentional ingestion while 36% were from an unintentional ingestion. In 17% of the cases, the reactive agent was topically applied either as a lotion or bath solution. There were also cases where the child used a product that was contaminated (5%, n=6) or adulterated (2%, n=2) causing an adverse event. In 7% of the studies (n=9), the adverse event was fatal to the individual. Seventy percent reported that the patient had a complete resolution of symptoms following hospitalization. There was a resolution of symptoms with medication or outpatient therapy in 14% of the cases.

Table 2 includes the 17 items based on the AER guidelines and the number of AERs that reflected adherence to this item. Fifty-two percent of studies documented the Latin binomial of the herb ingredients. Dosage information revealed that 59% of cases reported the amount of herb taken by the patient. Forty four percent of reports included the duration of herb use before the adverse event. Twenty two percent included an assessment of the potential concomitant therapies that could have been influential in the adverse events.

Table 2. Adherence Criteria of Adverse Events Case Reports Based on the ISP's “Guidelines for submitting adverse event reports for publication”.

| Item | Description | Point Value | Cases with item present (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 1 | 127 (99) | |

| Sex | 1 | 110 (86) | |

| Current Health Status | Disease or symptoms being treated with suspect herb | 1 | 115 (90) |

| Medical History | Medical history relevant to adverse event | 1 | 101 (79) |

| Physical Examination | Abnormal physical or laboratory findings. | 1 | 121 (95) |

| Patient Disposition | Presence or absence of death, life-threatening circumstances, hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization or significant disability | 1 | 127 (99) |

| Herb Information | |||

| Latin binomial name of herb ingredients | 1 | 66 (52) | |

| Generic name – proprietary name of herb | 1 | 113 (88) | |

| Plant part(s) | 1 | 52 (41) | |

| Type of Preparation – crude herb or extract | 1 | 120 (94) | |

| Manufacturer – producer of herb | 1 | 26 (20) | |

| Dosage | |||

| Dosage – approximate amount of herb | 1 | 76 (59) | |

| Duration of Therapy – how long herb has been taken | 1 | 118 (92) | |

| Duration of herb use before adverse event | Therapy duration before adverse event and it's interface with the adverse event | 1 | 52 (44) |

| Concomitant Therapies | Assessment of potential contribution of concomitant therapies | 1 | 28 (22) |

| Description of Adverse Event | Description of adverse event and its severity compared with established definitions and outcome of adverse event. | 1 | 127 (99) |

| Discussion | Presence or absence of evidence supporting causal link including timing, dechallenge and rechallenge (or state why these were not possible) Discussion of previous reports of adverse event in biomedical journal or product labeling. |

1 | 119 (93) |

| Total Points Achievable | 17 |

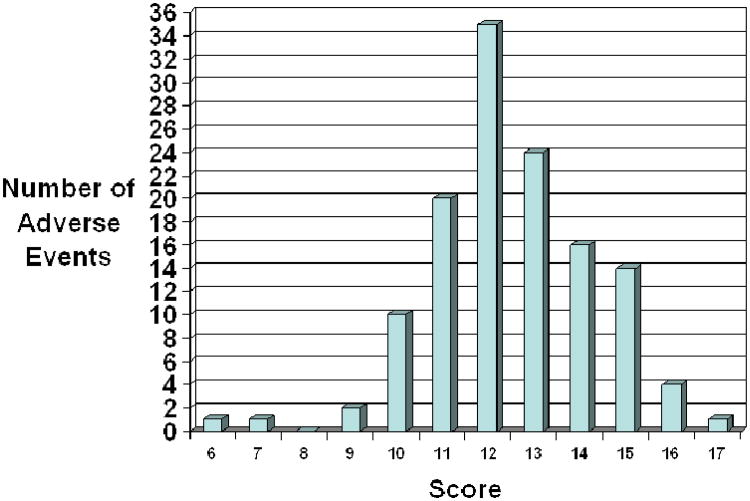

Figure 2 displays the distribution of adherence scores for adverse events. Adherence scores ranged from 6 to 17. The mean for all scores was 12.5 (S.D. 1.8) There was no association between a higher score and whether the case report was documented in an adult journal or a pediatric journal (p=0.87). There was no correlation between a higher score and the year of publication (p=0.51). Table 3 lists several examples of cases that met or almost met all the AER guidelines (15 to 17 points). This table does not address causality but is for the reader to have examples of case reports with good documentation.

Figure 2. Number of Adverse Events by Adherence Score.

Table 3. Adverse Event Reports with Adherence Scores of 15 or greater.

| Reference (Author, Year) | Adherence Score | Herb Common Name (Latin name) | Age of Child | Adverse Event | Route of Administration or Exposure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panis et al. 2005 11 | 17 | Fleeceflower root (Polygonum multiflorum) | 5 years | Acute toxic hepatitis | Intentionally ingested tablets adulterated with anthraquinones | Resolution of symptoms |

| Humberston et al. 2003 12 | 16 | Kava kava (Piper methysticum) | 14 years | Acute hepatitis | Intentional ingestion | Liver transplant |

| Morris et al. 2003 13 | 16 | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 4 years | Ataxia, unresponsiveness | Unintentional ingestion | Resolution of symptoms |

| Koren et al. 1990 14 | 16 | Ginseng (Ginseng siberian) | 1 day | Neonatal hirsutism, androgenous effects | Mother took ginseng while pregnant and breastfeeding for 2 weeks | Resolution of symptoms |

| Jones et al. 1998 15 | 16 | Blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides) | 1 day | Neonatal congestive heart failure | Mother used blue cohosh tablets 1 month prior to delivery to induce delivery | Hospitalization in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), at 2 year follow up cardiomegaly present and patient receiving digoxin |

| Chan et al. 2007 16 | 15 | Pearl Powder (traditional herbal medicine formula) | 9 days | Cyanosis with methemoglobine mia | Intentional ingestion administered for poor feeding | Resolution of symptoms |

| Henley et. al. 2007 17 | 15 | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 10 years | Gynecomastia | Topically applied to hair with lavender (Lavendula augustifolia) | Resolution of symptoms |

| Martin et al. 2007 18 | 15 | Yerba de mate (Ilex paraguariensis) | 1 day | Neonatal withdrawal | Mother drank mate during pregnancy | Reduction of symptoms |

| Rafaat et al. 2000 19 | 15 | Garlic (Allium sativum) | 3 months | Blisters, lesions, and third degree burns | Garlic bulbs applied to feet and ankles | Wounds healed |

| Garty et al. 2006 20 | 15 | Garlic (Allium sativum) | 6 months | Ulceration and lesion | Crushed garlic cloves fixed to wrists | Wounds healed |

| Darben et al. 1998 21 | 15 | Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) | 6 years | Ataxia, weakness, unconsciousness | Topically applied bandages soaked with eucalyptus | Resolution of symptoms |

| Bagheri et al. 1998 22 | 15 | Valerian, Ballote, hawthorn, passiflora, kola (Valerian aofficinalis, Ballotanigra, Crataegus oxyacantha, Passiflora incarnata, Cola nitida) | 13 years | Acute hepatitis | Intentional ingestion of pill for anxiety | Liver transplant |

| Schmid et al. 2006 23 | 15 | Broom bush (Retama raetam) | 7 days | Respiratory failure | Intentional ingestion of tea | Hospitalization in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), resolution of symptoms |

| Bhowmick et al. 2007 24 | 15 | Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis | 11 years | Diabetic ketoacidosis, hypernatremia, hyperosmolality | Intentional ingestion of tablets for polyuria | Discharged with instructions to discontinue goldenseal |

| Asiri et al. 2006 25 | 15 | Myrrh, mahaleb, anise, hauwa (Commiphora molmol, Prunusmahaleb, Pimpinella anisum, Launaea capitata) | 10 months | Lead toxicity | Herbs pasted to gums for teething | Death of infant |

| Corazza et al. 2006 26 | 15 | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 16 years | Acute vulvitis | Oil applied as a Kolorex cream with pepper tree (Pseudowintera colorata) | Resolution of symptoms |

| Florkowski et al. 2002 27 | 15 | Multi ingredient with yellow powder and snake extract | 10 years | Adrenal suppression | Intentional ingestion of capsule for asthma and eczema | Resolution of Symptoms |

| Roulet et al. 1988 28 | 15 | Herbal tea | 5 days | Hepatic vasoocclusive disease | Herbal tea containing pyrrolidizine alkaloids consumed through pregnancy | Death of infant |

| Khandpur et al. 2008 29 | 15 | Ayurvedic products | 11 years | Hypo and hyper pigmented macules all over body, thickening of palms and soles, abdominal pain | Pills and powders intentionally ingested – products contaminated with arsenic | Resolution of symptoms |

Discussion

Upon review of the literature, we found a wide spectrum of AEs related to herb use in children. We must bring attention to the poor adherence to complete documentation in the case reports. In our analysis of 128 AERs, the average adherence score for all cases was 12.5 with the highest attainable score being 17. This is concerning, because if AEs are not properly documented, it can be difficult to assess causality of the AE. One cannot determine if an herbal product caused the AE if all the information about the patient and the product are not known or reported. Our results highlight the need for standardized guidelines for reporting AERs in children following herbal products. There are models of developing standardized reporting guidelines such as the CONSORT for randomized controlled studies and the STROBE guidelines for observational studies. 5,6

The widespread use of herbal products among children necessitates the exploration into the safety of these herbs. While randomized controlled trials are the modern-day gold standard for evaluating efficacy. The sample size is often too small to detect rare but serious harms and the length of follow-up is often too short to detect harms after prolonged exposure.6 In contrast, case reports can be good sources of information about adverse events, especially for new/emerging harms, those that are rare, or occur after prolonged use. Case reports, however, cannot determine the incidence of specific adverse events. They may only highlight one or several reports of an occurrence. In order to provide an accurate signal of harm, these reports must clarify certain details about the adverse event.

Like drug AERs, herbal AERs often require additional information, including details of the herbal product (e.g., dose/amount taken and duration, exact names of ingredients as listed on the product label), de-challenge/re-challenge information, and patient characteristics. As noted in the reports on products containing ephedra, insufficiently documented case reports hamper informed judgment in evaluating relationships between AERs and a product.7 For example, the person filing the AER should retain a sample of the product, especially if the adverse event is serious, in case testing for adulteration or contamination is indicated.

In our review, an important finding is the high representation of unintentional ingestions (36%). As with drugs, herbal exposures can be unintentional in nature, either as the result of misuse by a parent or poor supervision of the child. A study by Gryzlak et al. examined poison control center reports from 64 centers across the U.S. and focused specifically on two of the most widely used herbs, Echinacea and St. John's wort. They found that the majority of exposures for both herbs were in children under the age of 5 and noted that many exposures were coded as unintentional.8

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) requires that oral prescription drugs for children be dispensed in child-resistant packaging unless the drug is exempted or the patient or prescriber requests otherwise. The only dietary supplement with a special packaging requirement is iron-containing drugs and dietary supplements that contain 250 mg or more of elemental iron.9 We also found that some exposures occurred because of an herbal product was administered in a manner contradicting its traditional intended use. For example, while the product is beneficial if topically applied, it may cause a negative reaction if ingested (e.g., aloe). It also indicates the need for careful labeling of herbal products, clear instructions for use, and monitoring of use.

Our adherence rubric was based on the ISE's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication.”4 Only one case report contained all the necessary components of a comprehensive adverse event report according to the most basic guidelines. The most commonly missed items were information about the herbal product and the use of any concomitant therapies that could have interacted with the herb. While there were no correlations between adherence score and characteristics of the journal (year of publication or adult versus pediatric journal), there is considerable room for improvement in reporting AEs.

Research suggests that reporting of AEs in case reports has improved over the last decade.10 Ideally, an AER would contain the most accurate and complete information available about the episode. However, one could argue that certain components of the AER may be more important than others. Many of the reports contained a wealth of information but failed to discuss duration of therapy or the chance for concomitant therapies. This could be problematic as there is no way of assessing whether an interaction between therapies could have occurred.

There are a many limitations in our study. First, we did not include case reports where herbs were used as recreational drugs, thus underestimating the true number of adverse events in the literature. We only included English language case reports, thus, not addressing if non-English case reports show similar trends in documentation and types of adverse events. We also limited our search to children under 18 years old, thus, not addressing adverse events from herbal sport supplements that are often used by college age and older adolescents

In terms of the adherence to the ISE's guidelines, we looked at only peer reviewed journals, not AERs from poison control centers or government databases (MedWatch). Lastly, we did not restrict our searches to herbs that are commonly used in pediatric populations. Thus, we found great diversity in products represented and our findings include very rare products that are likely not generalizable in the larger US pediatric population.

Conclusion

Our research suggests that there is need of improvement in reporting of AEs in case reports. While there are no standardized guidelines for all medical journals for case reports, our systematic review provides a starting point for future discussions about appropriate guidelines for AERs. Adherence indicators are necessary to establish high quality case reports which provide the most comprehensive information about the products (e.g., dietary supplements or medications) and the case history so that causality can be evaluated. Parents and health practitioners need to be aware of risks and benefits of herbal supplements. This can only be accomplished if there are high quality adverse events reports they can trust.

Supplementary Material

Take Home Messages

There is considerable room for improvement in reporting AEs.

In our review, an important finding is the high representation of unintentional ingestions.

We also found that some exposures in our review occurred because of an administration that contradicts its traditional intended use.

Only one case report contained all the necessary components of a comprehensive adverse event report according to the most basic guidelines from the International Society of Epidemiology's (ISE) “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication”.

The most commonly missed items were information about the herbal product and the use of any concomitant therapies that could have interacted with the herb.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Paula Gardiner is the recipient of Grant Number K07 AT005463-01A1 from the National Center For Complementary &Alternative Medicine. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Complementary & Alternative Medicine or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sunita Vohra receives salary support from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions as a Health Scholar.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United states, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dietary supplement and nonprescription drug consumer protection act. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennehy CE, Tsourounis C, Horn AJ. Dietary supplement-related adverse events reported to the california poison control system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(14):1476–1482. doi: 10.2146/ajhp040412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly WN, Arellano FM, Barnes J, et al. Guidelines for submitting adverse event reports for publication. Drug Saf. 2007;30(5):367–373. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahim S, Clarke M. STROBE: New standards for reporting observational epidemiology, a chance to improve. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):946–948. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haller CA, Benowitz NL. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(25):1833–1838. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gryzlak BM, Wallace RB, Zimmerman MB, Nisly NL. National surveillance of herbal dietary supplement exposures: The poison control center experience. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(9):947–957. doi: 10.1002/pds.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Requirements under the poison prevention packaging act 16 CFR 1700. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung SK, Hillier S, Ernst E. Case reports of adverse effects of herbal medicinal products (HMPs): A quality assessment. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(5):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panis B, Wong DR, Hooymans PM, De Smet PA, Rosias PP. Recurrent toxic hepatitis in a caucasian girl related to the use of shou-wu-pian, a chinese herbal preparation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(2):256–258. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000164699.41282.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humberston CL, Akhtar J, Krenzelok EP. Acute hepatitis induced by kava kava. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41(2):109–113. doi: 10.1081/clt-120019123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris MC, Donoghue A, Markowitz JA, Osterhoudt KC. Ingestion of tea tree oil (melaleuca oil) by a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(3):169–171. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000081241.98249.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koren G, Randor S, Martin S, Danneman D. Maternal ginseng use associated with neonatal androgenization. JAMA. 1990;264(22):2866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones TK, Lawson BM. Profound neonatal congestive heart failure caused by maternal consumption of blue cohosh herbal medication. J Pediatr. 1998;132(3):550–552. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan B, Ui LQ, Ming TP, et al. Methemoglobinemia after ingestion of chinese herbal medicine in a 9-day-old infant. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45(3):281–283. doi: 10.1080/15563650601118028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, Bloch CA. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):479–485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin I, Lopez-Vilchez MA, Mur A, et al. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome after chronic maternal drinking of mate. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29(1):127–129. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803257ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rafaat M, Leung AK. Garlic burns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(6):475–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garty BZ. Garlic burns. Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):658–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darben T, Cominos B, Lee CT. Topical eucalyptus oil poisoning. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39(4):265–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagheri H, Broue P, Lacroix I, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure after herbal medicine ingestion in children. Therapie. 1998;53(1):82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid T, Turner D, Oberbaum M, Finkelstein Y, Bass R, Kleid D. Respiratory failure in a neonate after folk treatment with broom bush (retama raetam) extract. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(2):124–126. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000199560.96356.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhowmick SK, Hundley OT, Rettig KR. Severe hypernatremia and hyperosmolality exacerbated by an herbal preparation in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007;46(9):831–834. doi: 10.1177/0009922807303042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asiri Y. Lead toxicity of an infant from home made herbal remedy. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2006;14(2) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corazza M, Lauriola MM, Poli F, Virgili A. Contact vulvitis due to pseudowintera colorata in a topical herbal medicament. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(2):178–179. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Florkowski CM, Elder PA, Lewis JG, et al. Two cases of adrenal suppression following a chinese herbal remedy: A cause for concern? N Z Med J. 2002;115(1153):223–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roulet M, Laurini R, Rivier L, Calame A. Hepatic veno-occlusive disease in newborn infant of a woman drinking herbal tea. J Pediatr. 1988;112(3):433–436. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khandpur S, Malhotra AK, Bhatia V, et al. Chronic arsenic toxicity from ayurvedic medicines. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(6):618–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.