Abstract

TRPV (transient receptor potential, vanilloid) channels are a family of nonselective cation channels that are activated by a wide variety of chemical and physical stimuli. TRPV1 channels are highly expressed in sensory neurons in the peripheral nervous system. However, a number of studies have also reported TRPV channels in the brain, though their functions are less well understood. In the hippocampus, the TRPV1 channel is a novel mediator of long-term depression (LTD) at excitatory synapses on interneurons. Here we tested the role of other TRPV channels in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, using hippocampal slices from Trpv1, Trpv3 and Trpv4 knockout (KO) mice. LTD at excitatory synapses on s. radiatum hippocampal interneurons was attenuated in slices from Trpv3 KO mice (as well as in Trpv1 KO mice as previously reported), but not in slices from Trpv4 KO mice. A previous study found that in hippocampal area CA1, slices from Trpv1 KO mice have reduced tetanus-induced long-term potentiation (LTP) following high-frequency stimulation; here we confirmed this and found a similar reduction in Trpv3 KO mice. We hypothesized that the loss of LTD at the excitatory synapses on local inhibitory interneurons caused the attenuated LTP in the mutants. Consistent with this idea, blocking GABAergic inhibition rescued LTP in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice. Our findings suggest a novel role for TRPV3 channels in synaptic plasticity and provide a possible mechanism by which TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels modulate hippocampal output.

Introduction

Transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) channels are multi-modally activated, nonselective cation channels most prominently expressed in peripheral sensory neurons, where they integrate thermal, mechanical, and nociceptive stimuli (Caterina 2007; Nilius and Owsianik 2011). The peripheral TRPV3 channel is activated at temperatures above 34°C, while TRPV1 is activated at temperatures greater than 43°C (Caterina, et al. 2000; Caterina, et al. 1997; Peier, et al. 2002; Smith, et al. 2002; Xu, et al. 2002). In addition to activation by temperature, TRPV channels also open in response to endogenous and exogenous chemical stimuli. TRPV1 channels can be activated by capsaicin, acid, anandamide and the arachidonic acid metabolites, HPETEs, while TRPV3 channels can be activated by free fatty acids and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (Tominaga et al., 1998; Piomelli et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2006; Fernandes et al., 2008). The genes that encode TRPV1 and TRPV3 are located adjacent to one other in the human and mouse genomes and exhibit about 50% overall sequence similarity. TRPV4 shares 45% sequence homology with TRPV1, and was first identified as an osmolarity sensor (Strotmann et al., 2000). TRPV4 channels are also gated by temperature, as well as by phorbol esters, arachidonic acid and anandamide (Nilius, 2004; Gao et al., 2003; Guler et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2002; Moran et al., 2011).

Growing evidence from diverse experimental approaches, including in situ hybridization and RT-PCR, supports the expression of TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3 and TRPV4 in the brain (Caterina et al., 2000; Mezey et al., 2000; Sanchez et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2004; Toth et al., 2005; Cristino et al., 2006; Shibasaki et al., 2007; Moussaieff et al., 2008; Cavanaugh et al., 2011). Previous studies indicate a functional role for TRPV1 in a variety of brain regions including area CA1 and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, ventral tegmental area, amygdala, striatum, brainstem, substantia nigra, developing superior colliculus, locus coeruleus, hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens (Sasamura et al., 1998; Doyle et al., 2002; Marinelli et al., 2002; Marinelli et al., 2003; Marinelli et al., 2005; Marinelli et al., 2007; Gibson et al., 2008; Maione et al., 2009; Musella et al., 2009; Chavez et al., 2010; Grueter et al., 2010; Peters et al., 2011; Puente et al., 2011; Zschenderlein et al., 2011).

TRPV1 channels appear to regulate synaptic function within different brain regions by diverse mechanisms. LTD at glutamatergic synapses on hippocampal GABAergic interneurons results from persistently reduced neurotransmitter release and is dependent upon TRPV1 channels (Gibson et al., 2008; McMahon and Kauer, 1997). Despite the diversity of interneuron types in the hippocampus, this form of LTD is observed in recordings from the majority of interneurons, consistent with the hypothesis that the LTD is mediated presynaptically (McMahon and Kauer, 1997). The TRPV1 channels are most likely located on presynaptic terminals, as a TRPV1 channel antagonist delivered into the interneuron has no effect on LTD (Gibson et al., 2008; McMahon and Kauer, 1997). Persistent synaptic depression at this site in the circuit is expected to reduce the inhibitory drive provided by GABAergic interneurons and to disinhibit the myriad of pyramidal cells they innervate. TRPV1-dependent LTD has also been reported in the dentate gyrus and nucleus accumbens where it is mediated by internalization of AMPA receptors (Chavez et al., 2010; Grueter et al., 2010). TRPV1 channels have also been implicated in LTD observed at synapses in extended amygdala and superior colliculus (Maione et al., 2009; Puente et al., 2011), and in nociceptive synapses of the leech (Yuan and Burrell, 2010).

What effects do TRPV1 channels have on the hippocampal circuit? After high-frequency electrical stimulation (HFS), slices from Trpv1 KO mice have significantly less LTP at synapses on hippocampal pyramidal cells than slices from wild type (WT) mice (Marsch et al., 2007). Furthermore, capsaicin significantly enhances area CA1 LTP, but this enhancement is prevented by blocking GABAA receptors (Bennion et al., 2011), suggesting that TRPV1 channels regulate GABAergic control of pyramidal cell excitability. In vivo, intrahippocampal infusion of capsaicin prevents acute stress-induced memory impairment, while the selective TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine infused intrahippocampally disrupts consolidation of strong contextual fear memories (Genro et al., 2012; Li et al., 2008). Hippocampal-linked behavioral phenotypes such as short-term memory loss, altered contextual fear processing and decreased anxiety have been noted in Trpv1 KO mice (Marsch et al., 2007; You et al., 2012). Together these data indirectly support a role of the TRPV1 channel in normal hippocampal function.

Considerably less is known about the role of TRPV3 channels in the brain, but WT mice injected with incensole acetate, a potent TRPV3 activator, exhibit anxiolytic and antidepressant-like behavior that is absent in Trpv3 KO mice (Moussaieff et al., 2008). In contrast to TRPV1, TRPV3 channels are capsaicin-insensitive. Currently available pharmacological agonists for the TRPV3 channel include 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), camphor, and carvracol, but these are relatively nonspecific, hampering the characterization of the channel in native cells (Smith et al., 2002; Vriens et al., 2009; Moran et al., 2011). For example, in addition to activating TRPV1, V2 and V3 channels, 2-APB inhibits inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (Maruyama et al., 1997) as well as members of the TRPC and TRPM family (Ramsey et al., 2006), and camphor activates both TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels (Xu et al., 2006). To circumvent these limitations, we have used electrophysiological recordings from genetically altered mice to study the role of TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels in hippocampal circuit function.

Using slices from knockout mice, the data we report here suggest that TRPV1 and TRPV3, but not TRPV4 channels, are required for LTD at excitatory synapses on hippocampal interneurons. We also observed that HFS-induced LTP at CA3-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses was attenuated in hippocampal slices from Trpv1 and Trpv3 KO mice. This attenuation could be reversed by blocking GABAergic inhibition, consistent with the interpretation that the loss of LTD at interneuron synapses influences hippocampal circuit behavior.

Material and Methods

Animals and brain slice preparation

All animal protocols were approved by the Brown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Trpv1 KO, Trpv3 KO, and Trpv4 KO, and wild type littermates, as well as C57BL/6 mice (Charles River), aged between 15 and 31 days, were utilized for these experiments (Caterina et al., 2000; Liedtke and Friedman 2003; Moqrich et al., 2005). Animals were genotyped using modified PCR protocols (Caterina et al., 2000; Liedtke and Friedman 2003; Moqrich et al., 2005). Data from wild type littermates of Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice showed no significant differences from C57BL/6 control mice and as a result the data from these groups were pooled. Only one brain slice per mouse was used for each experiment, so the reported n value represents the number of animals.

Our basic slice methods have been described previously (Gibson et al., 2008). Briefly, animals were anaesthetized using isoflurane and decapitated, or instead injected intraperitoneally with ketamine (75 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (0.5 mg/kg) and then perfused intracardially with 4°C artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) prior to decapitation. Slices were cut in aCSF at 4°C and then stored for at least 1 hr at room temperature in aCSF (in mM): 119 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, and 11 dextrose, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (pH 7.4), before being transferred to the recording chamber. Recording aCSF contained elevated divalent cations (high divalent aCSF: as above except 4 mM CaCl2 and 4 mM MgCl2, replacing MgSO4), and a surgical cut was made between the CA3 and CA1 regions to reduce epileptiform activity.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Slices were perfused with oxygenated aCSF at 28-31°C at a flow rate of 1-2 ml/min. TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels exhibit minimal activation at temperatures below 34°C, so in our experiments we do not expect significant temperature-dependent effects (Caterina et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2002, Smith et al., 2002); TRPV4 channels have been reported to open at temperatures as low as 27°C, so it is possible that in our experimental setup there is some tonic activation of these channels. The temperature was held constant during a given experiment, however, so we do not anticipate that there were any temperature-induced channel openings once the slice had been placed in the recording chamber. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from interneurons in the CA1 stratum radiatum of the hippocampus as described (Gibson et al., 2008). Hippocampal interneurons comprise a diverse group of cells, with differing anatomical, electrophysiological and biochemical characteristics. Nonetheless, we consistently find that the majority of interneurons from which we record exhibit LTD independent of morphology (McMahon and Kauer, 1997). This observation may be a consequence of presynaptically mediated LTD at a common set of innervating afferents (Gibson et al., 2008). Patch pipettes contained (in mM): 117 cesium gluconate, 2.8 NaCl, 5 MgCl2, 20 HEPES, 2 ATP-Na, 0.3 GTP-Na, and 0.6 EGTA. Interneurons were voltage clamped at -70 mV (not corrected for the liquid junction potential of ~ 10 mV). Interneuron LTD can be initiated even after 45 minutes in the whole-cell configuration (McMahon and Kauer, 1997). AMPAR EPSCs were isolated pharmacologically with picrotoxin (100 μM) and D-AP5 (50 μM) to block GABAA and NMDA receptors, respectively. After at least 10 minutes of stable EPSCs, LTD was induced using high-frequency stimulation (HFS; two 1 s trains at 100 Hz, intertrain interval 20 s, at 1.5 times test current intensity). Control experiments were interleaved with knockout experiments. The cell input resistance and series resistance were monitored, and cells were discarded if these values changed by more than 15% throughout the experiment. EPSCs were amplified and recorded using pClamp 10.

Extracellular field potential recordings were made by stimulating in s. radiatum and recording from s. radiatum using an electrode filled with 2 N NaCl, as previously described (Gibson, et al. 2008), except that high-divalent aCSF was used to match our whole-cell experimental conditions. D-AP5 was not included, and picrotoxin was not present except as specified in the text and legends. LTP was induced using the same protocol used to induce interneuron LTD (HFS; two 1 s trains at 100 Hz, intertrain interval 20 s, at 1.5 times test current intensity).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed as previously described (Gibson et al., 2008). Briefly, the maximal initial slope of fEPSPs or the peak amplitude of EPSCs was measured using LabVIEW-based software (National Instruments, Austin, TX) or Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA). EPSC amplitude values were compared to controls 7-11 min after HFS, and fEPSP slopes were compared to controls 15-20 min after HFS. Measurements of area under the curve were made for the responses to tetanus of interneurons in which no escape from voltage-clamp occurred in either tetanus, and these values were normalized to the area under the curve of the first EPSC in the first train, to control for variability in the size of the starting EPSC.

Data values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. (n=number of animals). For comparisons between two data sets we analyzed the data with an unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test and for tests involving more than two data sets we used a 1-way ANOVA with a Dunn’s Multiple Comparison Test when appropriate. For area under the curve measurements, a paired 2-tailed Student’s t test was used. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data sets that violated the assumption of normality based upon D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test were transformed (reciprocal of the value) and reanalyzed.

Results

Trpv3 KO and Trpv1 KO but not Trpv4 KO mice lack long-term depression at excitatory synapses on CA1 interneurons

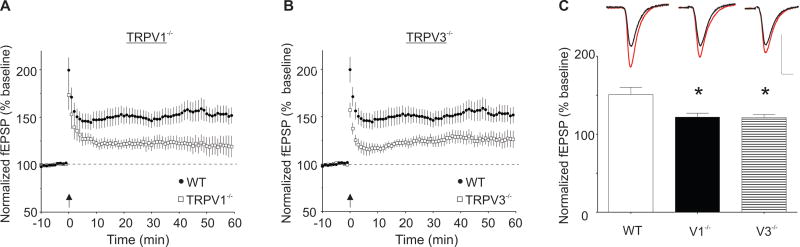

Consistent with our previous results, slices from Trpv1 KO mice lacked interneuron LTD (Figure 1A; EPSC amplitudes after LTD induction (% baseline values): WT, 75±4, n=15; Trpv1 KO, 106±10, n=6; t(19)=3.79, p<0.05). Other TRPV family members have also been reported in hippocampus, so we tested whether interneuron LTD is intact in slices from Trpv3 KO and Trpv4 KO mice. Surprisingly, interneuron LTD was also absent in slices from Trpv3 KO mice (Figure 1B, right inset; EPSC amplitudes after LTD induction (% baseline values): WT, 75±4, n=15; Trpv3 KO, 111±11, n=11; t(24)=3.50, p<0.05). The magnitude of EPSCs from Trpv3 KO mice exhibited considerable variability after HFS (Figure 1B) ranging from mild depression (n=5), no change (n=2) to potentiation (n=4).

Figure 1. Slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO Mice Lack Interneuron LTD.

(A) A single experiment illustrating that interneurons from Trpv1 KO mice lack HFS-induced LTD of excitatory synapses onto CA1 stratum radiatum interneurons. HFS was delivered at the arrow in all figures. (B) Averaged experiments from interneurons from WT (closed circles) and Trpv1 KO mice (open squares). Insets: ten averaged EPSCs from a single experiment taken at the times indicated before (1, black) and 15-20 min after HFS (2, red). Calibration: 50 pA, 5 ms. (C) Scatter plot of individual experiments illustrating LTD observed in each cell. (D) Single experiment showing that interneurons from Trpv3 KO mice also lack LTD. (E) Averaged experiments from WT (closed circles) and Trpv3 KO mice (open squares). (F) Scatter plot of individual experiments illustrate EPSC amplitudes from interneurons in WT and Trpv3 KO mice.

We measured the area under the curve during the first and second tetani to interneurons from wild type mice, and found that the area of the second tetanus was significantly smaller than that of the first, consistent with the induction of LTD during the first tetanus. No such difference was observed in interneurons from Trpv1 KO mice (wild type animals: tetanus 1, 107±9; tetanus 2, 101±11; n=10, p<0.05; Trpv1-/- animals: tetanus 1, 131± 32; tetanus 2, 132±30 n=5, n.s.).

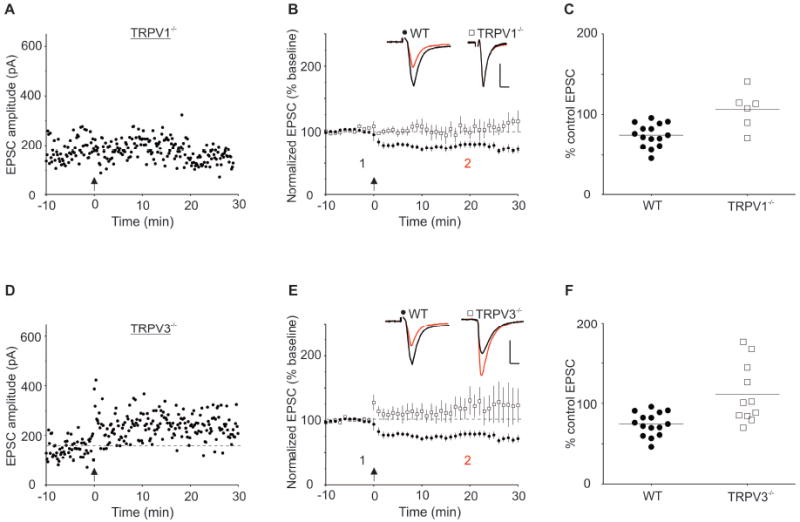

In contrast to slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice, slices from Trpv4 KO mice have apparently normal LTD compared to WT control mice (Figure 2; EPSC amplitudes after LTD induction (% baseline values): WT, 75±4, n=15; Trpv4 KO, 78±7, n=7; t(20)=0.46, p=0.65). This demonstrates that deletion of a single TRPV family member does not necessarily prevent LTD at this synapse.

Figure 2. Slices from Trpv4 KO Mice Express Normal Interneuron LTD.

(A) Individual experiment showing LTD in an interneuron from a Trpv4 KO mouse. (B) Averaged experiments from WT (closed circles) and Trpv4 KO mice (open squares) showing that that interneurons from Trpv4 KO mice express HFS-induced LTD comparable to those from WT mice. Insets: ten averaged EPSCs from a single experiment taken at the times indicated before (1, black) and 15-20 min after HFS (2, red). Calibration: 50 pA, 5 ms. (C) Scatter plot of individual experiments illustrating LTD magnitude in each experiment.

Long-term potentiation at the CA3-CA1 pyramidal cell synapse is reduced in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice

Since the discovery of hippocampal LTP indirect evidence supported the idea that following HFS, LTP at hippocampal excitatory synapses is accompanied by a relative decrease in GABAAR-mediated inhibition, a phenomenon termed E-S coupling (Bliss and Lomo, 1973; Wigstrom and Gustafsson, 1983). Later experiments indicated that E-S coupling is sensitive to GABAA receptor antagonists, suggesting that after tetanus, potentiation of synapses onto principal cells is greater than that at synapses onto interneurons (Wigstrom and Gustafsson, 1983; Abraham et al., 1987; Chavez-Noriega et al., 1989). We hypothesized that in the normal CA1 circuit, GABAergic inhibition of pyramidal cells is reduced during HFS because of simultaneous LTD induction at feedforward excitatory synapses on local interneurons (McMahon and Kauer, 1997; Figure 5). As a result of the reduced inhibitory drive to the pyramidal cells, more NMDARs could open, producing greater LTP. Conversely, when interneuron LTD is absent, as in Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice, one would expect greater inhibitory drive, fewer open NMDAR channels, and less pyramidal cell LTP. We first confirmed the earlier observation that Trpv1 KO mice exhibit significantly less CA3-CA1 LTP than WT controls (Marsch et al., 2007)(Figure 3A and 3C; fEPSP slopes after LTP induction (% baseline values): WT, 151±9, n=27; Trpv1 KO, 122±5, n=9; F(2, 46)=4.93, p<0.05). Since slices from Trpv3 KO mice also lack interneuron LTD, we hypothesized that they might also have attenuated HFS-induced LTP at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses. As predicted, slices from Trpv3 KO mice also exhibited attenuated LTP (Figure 3B and 3C; fEPSP slopes after LTP induction (% baseline values): WT, 151±9, n=27; Trpv3 KO, 121±4, n=13; F(2, 46)=4.93, p<0.05)

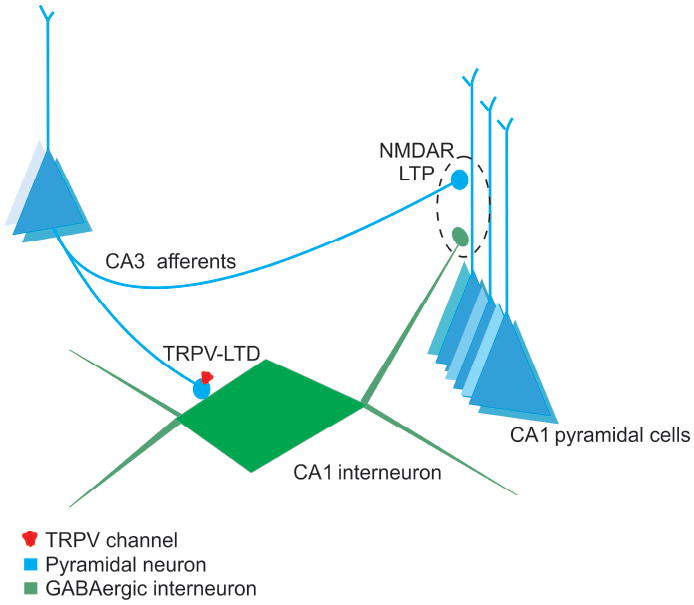

Figure 5. Diagram of Local Circuit effects of TRPV channels.

Glutamate release onto GABAergic interneurons (green) after HFS undergoes TRPV1/TRPV3-dependent LTD. The GABAergic depression may cause feedforward disinhibition, promoting NMDAR-dependent LTP in the excitatory glutamatergic (blue) synapses on CA1 pyramidal cells. A consequence of knocking out TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels is that excitatory synapses onto GABAergic interneurons no longer undergo LTD. As a result, inhibition of CA1 neurons is relatively greater during HFS, and the magnitude of LTP of the pyramidal cells is reduced.

Figure 3. Extracellular Recordings from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO Mice have Attenuated Pyramidal Cell LTP that is Rescued by a GABAAR Antagonist.

(A) Hippocampal slices from Trpv1 KO mice have significantly less LTP at CA3-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses. Time courses of averaged experiments from WT (closed circles) and Trpv1 KO mice (open squares). (B) CA3-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses from Trpv3 KO mice also have significantly less LTP (WT, closed circles; Trpv3 KO, open squares). (C) CA3-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses from Trpv1 KO (V1, black) and Trpv3 KO (V3, stripes) mice have significantly less LTP than those in WT mice (WT, white)(15 to 20 min post-HFS,* indicates p<0.05). Inset: averaged fEPSPs before (black) and 15-20 min post-HFS (red). Calibration, WT: 0.5 mV, 5 ms. Calibration, Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice: 0.4 mV, 5 ms.

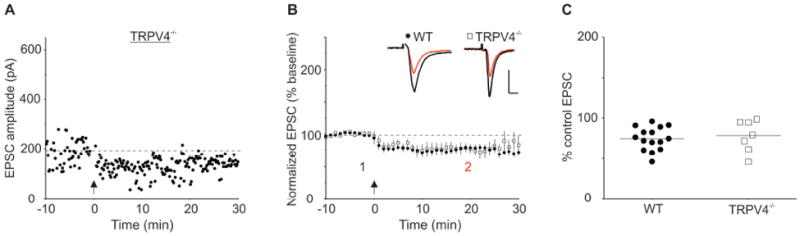

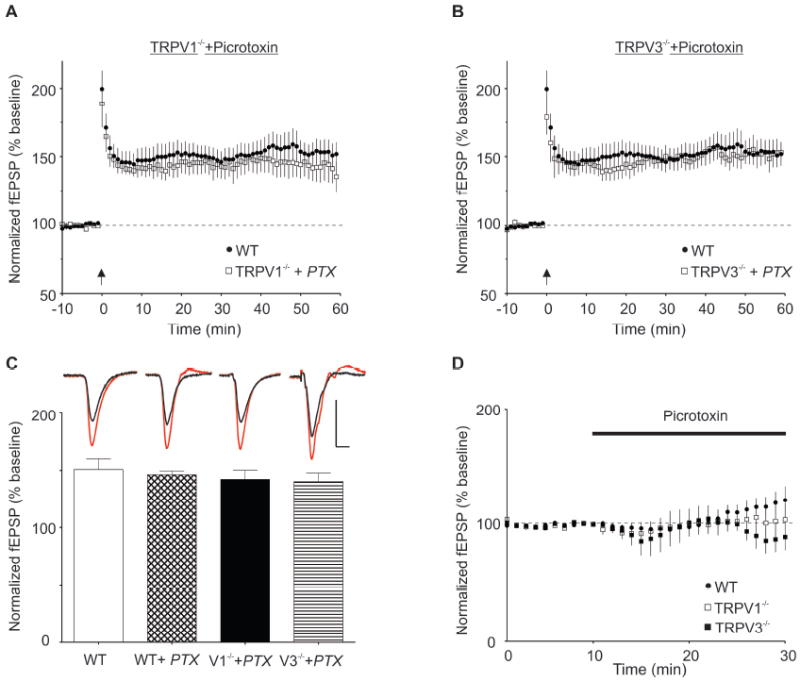

Blocking GABAARs rescues pyramidal cell LTP in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice

The attenuation of pyramidal cell LTP we observe in Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO slices could be explained if the lack of LTD at interneuron excitatory synapses leads to greater GABAAR-mediated inhibition during the HFS train, which in turn reduces NMDAR activation and consequently LTP. The work of Bennion et al. (2011) supports this idea; in rat slices, agonists of TRPV1 increase levels of HFS-induced LTP in area CA1, but this potentiation is not seen when GABAA receptors are blocked. Based on this hypothesis, we reasoned that taking interneuron-driven inhibition out of the circuit should normalize the LTP observed in slices from the knockout animals. As predicted, slices from Trpv1 KO mice exposed to picrotoxin (100 μM) prior to HFS produced LTP levels equivalent to those quantified in slices from WT animals (Figure 4A and 4D; fEPSP slopes after LTP induction (% baseline values): WT, 151±9, n=27; Trpv1 KO + PTX, 142±8, n=6; F (3, 39)=0.062, p=0.98). Moreover, LTP in slices from Trpv3 KO mice was also rescued with picrotoxin, similarly to slices from Trpv1 KO mice (Figure 4B and 4D; fEPSPs after LTP induction (% baseline values): WT, 151±9, n=27; Trpv3 KO + PTX, 141±7, n=6; F (3, 39) =0.062, p=0.98). Picrotoxin had little effect on the LTP magnitude in WT animals, consistent with previous findings (Wigstrom and Gustafsson, 1985)(Figure 4C; fEPSP slopes after LTP induction (% baseline values): WT, 151±9, n=27; WT+PTX, 146±3, n=4; F (3, 39)=0.062, p=0.98). Furthermore, picrotoxin application was accompanied by greater population spike generation in the field potential following HFS in all three genotypes, as previously reported when inhibition is blocked (Wigstrom and Gustafsson, 1985), indicating greater pyramidal cell excitability.

Figure 4. Blocking GABAA Receptors Rescues Pyramidal Cell LTP in Slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO Mice.

(A) When HFS is delivered in the presence of the GABAAR antagonist, picrotoxin (100 μM), LTP is rescued to WT levels in slices from Trpv1 KO mice (WT, closed circles; Trpv1 KO + picrotoxin, open squares). (B) Similarly, when HFS is delivered in the presence of picrotoxin, LTP in Trpv3 KO mice is rescued to WT levels (WT, closed circles; Trpv3 KO + picrotoxin, open squares). (C) Picrotoxin rescues LTP in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice (15 to 20 min post-HFS). Picrotoxin has no significant effect on WT fEPSPs (WT, n=27; WT + picrotoxin, 97± 2% of WT, n=4), while LTP from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice is not significantly different from that in WT slices. Top inset: averaged fEPSPs before (black) and 15-20 min after HFS (red). Calibration for WT, WT+PTX, Trpv3 KO + PTX: 0.5 mV, 5 ms. Calibration for Trpv1 KO + PTX 0.35 mV, 5 ms. (D) Picrotoxin does not significantly increase fEPSPs in untetanized slices from Trpv1 KO (open squares, n=4) and Trpv3 KO mice (closed squares, n=4) compared to slices from WT controls (closed circles, n=5).

If the lack of interneuron LTD is responsible for attenuated LTP in Trpv1 and Trpv3 KO mice during the induction of pyramidal cell LTP, then picrotoxin should rescue LTP when bath-applied prior to HFS, as we have shown. Moreover, if picrotoxin rescues LTP during the induction phase, then picrotoxin application after tetanic stimulation should not affect fEPSCs. As expected, once LTP was initiated, picrotoxin applied 20 minutes post HFS did not restore fEPSP values to WT control levels (fEPSP slopes, 18-20 min post picrotoxin (% baseline values), WT, 143 ± 8, n=11; Trpv1 KO, 129 ±6 n=8; Trpv3 106±5, n=4; data not shown). These data support a role for interneuron LTD during the induction, but not the maintenance phase of pyramidal cell LTP.

Blocking GABAergic inhibition rescued LTP in slices from both Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice, which might be explained by the lack of LTD during HFS. Alternatively, in the knockout animals, GABAergic inhibition could be persistently increased, diminishing the HFS-induced LTP magnitude. To test this possibility, we bath applied picrotoxin and monitored effects on fEPSPs without high-frequency stimulation. Picrotoxin alone did not significantly increase fEPSPs in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice compared to slices from WT controls, suggesting that the knockout mice do not have greater GABAergic inhibition as far as it influences the field potential (Figure 4D; fEPSP slopes, 18-20 min post picrotoxin (% baseline values), WT, 115%±6%, n=12; Trpv1 KO, 103% ±13%, n=3; Trpv3 KO, 88% ±11%, n=4; H=6.1. p=0.05).

Discussion

This study used Trpv3 KO and Trpv4 KO mice to expand upon our previous observation that TRPV1 channels mediate LTD at excitatory synapses on GABAergic interneurons (Gibson et al., 2008). We also confirmed a role for TRPV1 channels in the control of normal GABAergic inhibition in area CA1 (Bennion et al. 2011). We show that TRPV3 channels may also play a significant role in regulating synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Mice with genetic deletion of either TRPV1 or TRPV3 channels exhibited both a loss of interneuron LTD and attenuated HFS-induced LTP at pyramidal cell synapses. Supporting the idea that the reduction in LTP observed in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice may result from disrupting interneuron LTD, we blocked GABAA receptors and found that LTP was rescued to control levels. We speculate that this rescue was most likely a result of blocking the enhanced GABAergic feedforward inhibition by the interneurons on to pyramidal cells in the Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice (Figure 5), because our data suggest that slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice do not have enhanced tonic GABAergic inhibition in area CA1. Therefore, the rescue of LTP by picrotoxin may be the result of dynamic modulation of inhibition during LTP induction itself. Measurements of area under the curve during tetani to interneurons in wild type and Trpv1 KO mice are consistent with this interpretation.

Plasticity of glutamatergic synapses on s. radiatum interneuron seems to be far more diverse than previously appreciated. A proportion of the synapses expressing TRPV-mediated LTD have also been reported to exhibit NMDAR-dependent LTP in response to pairing depolarization and low-frequency stimulation (Lamsa et al., 2007; Lamsa et al., 2007b). We expect that these two forms of plasticity interact in a complex manner, determined by the interneuron subtypes and their projection sites. In any case, the observation of tetanus-induced LTD in the great majority of interneurons along with the current findings regarding pyramidal cell tetanus-induced LTP suggest that TRPV-dependent LTD can play a significant role in the local circuit.

We found that LTD at synapses on interneurons was absent and pyramidal cell LTP is attenuated in Trpv3 KO mice, however tools necessary to provide supporting information for the role of TRPV3 channels in the hippocampal circuit are limited. Currently available TRPV3 agonists and antagonists are not sufficiently selective for use in brain slice preparations; coapplication of the TRPV3 agonists camphor and 2-APB, successfully used to activate TRPV3 expressed in heterologous and cell culture systems (Xu et al., 2006; Grandl et al., 2008; Miyamoto et al., 2011), does not elicit responses that are TRPV3-selective under our experimental conditions (data not shown). We did observe considerable heterogeneity in interneuron LTD after tetanus in the Trpv3 KO mice (Figure 1B), and this may suggest that only a subpopulation of interneurons requires TRPV3 for LTD. Hippocampal interneurons are a diverse group of cells (Parra et al., 1998), and TRPV3 channels may be segregated to a specific interneuron subgroup. Despite our evidence that TRPV1-mediated LTD results from a presynaptic decrease in glutamate release (Gibson et al., 2008), without better tools, we cannot yet address the location and precise function of the relevant TRPV3 channels.

What are the endogenous TRPV3 activators in the hippocampus? Physiological brain temperature is close to the threshold for TRPV3 activation (Moqrich et al., 2005), and basal TRPV3 activity could contribute to resting membrane potential and neuronal excitability, as was shown for TRPV4 (Shibasaki et al., 2007). Additionally, TRPV3 activity could be modulated by endogenous lipids and inflammatory mediators secreted during pathological states (Basbaum et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2006).

It is surprising that deletion of either TRPV1 or TRPV3 channels eliminates interneuron LTD. TRPV3 may be necessary for the proper trafficking of TRPV1 channels to their site of action (or vice versa), and as a result slices from one null mouse may lack functional channels of the other subtype. There is precedent for this, as deletion of specific TRP channel subunits has been reported to influence the localization and trafficking of other ion channels (Kim et al., 2009; Kottgen et al., 2008; Venkatachalam et al., 2006). Another possibility is that deletion of TRPV3 channels may disrupt TRPV1 expression (Christoph et al., 2008). Alternatively, the TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels could in theory form obligate heteromeric channels so that the expression of both subtypes is necessary for the formation of functional channels required for LTD (Smith et al., 2002; Cheng et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2012). While homomeric TRPV channel complexes are favored, TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels reportedly are capable of forming heteromeric channels in HEK293 cells (Cheng et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2007; Hellwig et al., 2005), although demonstrating functional heteromeric channels in native tissue is difficult. Finally, the loss of LTD in slices from Trpv1 KO and Trpv3 KO mice may have nothing to do with expression, trafficking or proper assembly of TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels, but may be a result of functional homomeric channels that signal independently, each needed to mediate LTD in interneurons. At present it is difficult to resolve this question using biochemistry, calcium imaging, hybridization-based approaches, or genetic marking strategies, since the number of channels present is likely to be very small, impeding detection (c.f. Cavanaugh et al., 2011).

To our knowledge our data are the first to suggest that deleting TRPV3 channels can influence synaptic plasticity. We also find that interneuron LTD is TRPV4-independent, demonstrating TRPV-mediated specificity. Whether a TRPV1 channel identical to that expressed in the periphery is expressed in the hippocampus is still debated (Cavanaugh et al., 2011). Determining the TRPV subunit composition in the brain may be particularly relevant therapeutically, with the advent of TRPV1 receptors as drug targets for the treatment of pain. Based upon behavioral and functional data regarding synaptic plasticity in the brain, such therapeutic agents could influence emotive and cognitive function. If the brain TRPV1 channel complex has distinct structural properties from that in the periphery (e.g., subunit composition), drugs that target peripheral TRPV1 receptors specifically may avoid unwanted side effects in the brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Elena Oancea and Nadine Wicks for technical assistance as well as members of the Kauer lab for helpful discussions regarding the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS074612 (T.E.B.) and NS065251 (J.A.K.).

References

- Abraham WC, Gustafsson B, Wigstrom H. Long-term potentiation involves enhanced synaptic excitation relative to synaptic inhibition in guinea-pig hippocampus. J Physiol. 1987;363:367–380. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009;139(2):267–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennion D, Jensen T, Walther C, Hamblin J, Wallmann A, Couch J, Blickenstaff J, Castle M, Dean L, Beckstead S, et al. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 agonists modulate hippocampal CA1 LTP via the GABAergic system. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(4):730–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973;232(2):331–56. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ. Transient receptor potential ion channels as participants in thermosensation and thermoregulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292(1):R64–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00446.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288(5464):306–13. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Rosen TA, Tominaga M, Brake AJ, Julius D. A capsaicin-receptor homologue with a high threshold for noxious heat. Nature. 1999;398(6726):436–41. doi: 10.1038/18906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389(6653):816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ, Chesler AT, Jackson AC, Sigal YM, Yamanaka H, Grant R, O’Donnell D, Nicoll RA, Shah NM, Julius D, et al. Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31(13):5067–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6451-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Chiu CQ, Castillo PE. TRPV1 activation by endogenous anandamide triggers postsynaptic long-term depression in dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(12):1511–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Bliss TV, Halliwell JV. The EPSP-spike (E-S) component of long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampal slice is modulated by GABAergic but not cholinergic mechanisms. Neurosci Lett. 1989;104(1-2):58–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Yang F, Liu S, Colton CK, Wang C, Cui Y, Cao X, Zhu MX, Sun C, Wang K, et al. Heteromeric heat-sensitive transient receptor potential channels exhibit distinct temperature and chemical response. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(10):7279–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Yang F, Takanishi CL, Zheng J. Thermosensitive TRPV channel subunits coassemble into heteromeric channels with intermediate conductance and gating properties. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129(3):191–207. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph T, Bahrenberg G, De Vry J, Englberger W, Erdmann VA, Frech M, Kogel B, Rohl T, Schiene K, Schroder W, et al. Investigation of TRPV1 loss-of-function phenotypes in transgenic shRNA expressing and knockout mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37(3):579–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK, Lee H, Caterina MJ. Warm temperatures activate TRPV4 in mouse 308 keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(34):32037–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L, de Petrocellis L, Pryce G, Baker D, Guglielmotti V, Di Marzo V. Immunohistochemical localization of cannabinoid type 1 and vanilloid transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors in the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2006;139(4):1405–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle MW, Bailey TW, Jin YH, Andresen MC. Vanilloid receptors presynaptically modulate cranial visceral afferent synaptic transmission in nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurosci. 2002;22(18):8222–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J, Lorenzo IM, Andrade YN, Garcia-Elias A, Serra SA, Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Valverde MA. IP3 sensitizes TRPV4 channel to mechano- and osmotransducing messenger 5’-6’-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(1):143–155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Wu L, O’Neil RG. Temperature-modulated diversity of TRPV4 channel gating: activation by physical stresses and phorbol ester derivatives through protein kinase C-dependent and -independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(29):27129–27137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genro BP, de Oliveira Alvares L, Quillfeldt JA. Role of TRPV1 in consolidation of fear memories depends on the averseness of the conditioning procedure. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson HE, Edwards JG, Page RS, Van Hook MJ, Kauer JA. TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron. 2008;57(5):746–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandl J, Hu H, Bandell M, Bursulaya B, Schmidt M, Petrus M, Patapoutian A. Pore region of TRPV3 ion channel is specifically required for heat activation. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(9):1007–1013. doi: 10.1038/nn.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter BA, Brasnjo G, Malenka RC. Postsynaptic TRPV1 triggers cell type-specific long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(12):1519–25. doi: 10.1038/nn.2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guler AD, Lee H, Iida T, Shimizu I, Tominaga M, Caterina M. Heat-evoked activation of the ion channel, TRPV4. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6408–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06408.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig N, Albrecht N, Harteneck C, Schultz G, Schaefer M. Homo- and heteromeric assembly of TRPV channel subunits. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 5):917–28. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HZ, Xiao R, Wang C, Gao N, Colton CK, Wood JD, Zhu M. Potentiation of TRPV3 channel function by unsaturated fatty acids. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208(1):201–212. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Gibson HE. Hot flash: TRPV channels in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(4):215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Alvarez-Baron CP, Dryer SE. Canonical transient receptor potential channel (TRPC)3 and TRPC6 associate with large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels: role in BKCa trafficking to the surface of cultured podocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(3):466–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottgen M, Buchholz B, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Kotsis F, Fu X, Doerken M, Boehlke C, Steffl D, Tauber R, Wegierski T, et al. TRPP2 and TRPV4 form a polymodal sensory channel complex. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(3):437–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM, Lamsa KP. Long-etrm synaptic plasticity in hippocampal interneurons. Nat Rev Neuorsci. 2007;8(9):687–99. doi: 10.1038/nrn2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM, Moreau AW, Bakiri Y, Nicholson E. Plasticity of inhibition. Neuron. 2012;75(6):951–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K, Heeroma JH, Kullmann DM. Hebbian LTP in feed-forward inhibitory interneurons and the temporal fidelity of input discrimination. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(7):916–24. doi: 10.1038/nn1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K, Irvine EE, Giese KP, Kullmann DM. NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation in mouse hippocampal interneurons shows a unique dependence on Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Phisiol. 2007;583(Pt 3):885–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Duigou C, Kullmann DM. Group I mGluR agonist-evoked long-term potentiation in hippocampal oriens interneurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5777–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6265-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HB, Mao RR, Zhang JC, Yang Y, Cao J, Xu L. Antistress effect of TRPV1 channel on synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(4):286–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Friedman JM. Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4-/- mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(23):13698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735416100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YM, Mansuy IM, Kandel ER, Roder J. Calcineurin-mediated LTD of GABAergic inhibition underlies the increased excitability of CA1 neurons associated with LTP. Neuron. 2000;26:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione S, Cristino L, Migliozzi AL, Georgiou AL, Starowicz K, Salt TE, Di Marzo V. TRPV1 channels control synaptic plasticity in the developing superior colliculus. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 11):2521–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S, Di Marzo V, Berretta N, Matias I, Maccarrone M, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. Presynaptic facilitation of glutamatergic synapses to dopaminergic neurons of the rat substantia nigra by endogenous stimulation of vanilloid receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23(8):3136–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03136.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S, Di Marzo V, Florenzano F, Fezza F, Viscomi MT, van der Stelt M, Bernardi G, Molinari M, Maccarrone M, Mercuri NB. N-arachidonoyl-dopamine tunes synaptic transmission onto dopaminergic neurons by activating both cannabinoid and vanilloid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(2):298–308. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S, Pascucci T, Bernardi G, Puglisi-Allegra S, Mercuri NB. Activation of TRPV1 in the VTA excites dopaminergic neurons and increases chemical- and noxious-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(5):864–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S, Vaughan CW, Christie MJ, Connor M. Capsaicin activation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the rat locus coeruleus in vitro. J Physiol. 2002;543(Pt 2):531–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch R, Foeller E, Rammes G, Bunck M, Kossl M, Holsboer F, Zieglgansberger W, Landgraf R, Lutz B, Wotjak CT. Reduced anxiety, conditioned fear, and hippocampal long-term potentiation in transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptor-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27(4):832–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3303-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca2+ release. J Biochem. 1997;122(3):498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon LL, Kauer JA. Hippocampal interneurons express a novel form of synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 1997;18(2):295–305. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E, Toth ZE, Cortright DN, Arzubi MK, Krause JE, Elde R, Guo A, Blumberg PM, Szallasi A. Distribution of mRNA for vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1), and VR1-like immunoreactivity, in the central nervous system of the rat and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(7):3655–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060496197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T, Petrus M, Dubin AE, Pataboutian A. TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin. Nat Commu. 2011;2:369. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moqrich A, Hwang SW, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Murray AN, Spencer KS, Andahazy M, Story GM, Patapoutian A. Impaired thermosensation in mice lacking TRPV3, a heat and camphor sensor in the skin. Science. 2005;307(5714):1468–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1108609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M, McAlexander MA, Biro T, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channel as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(8):601–620. doi: 10.1038/nrd3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussaieff A, Rimmerman N, Bregman T, Straiker A, Felder CC, Shoham S, Kashman Y, Huang SM, Lee H, Shohami E, et al. Incensole acetate, an incense component, elicits psychoactivity by activating TRPV3 channels in the brain. FASEB J. 2008;22(8):3024–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-101865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musella A, De Chiara V, Rossi S, Prosperetti C, Bernardi G, Maccarrone M, Centonze D. TRPV1 channels facilitate glutamate transmission in the striatum. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B. Store-operated Ca2+ entry channels: still elusive! Sci STKE. 2004;2004(243):pe36. doi: 10.1126/stke.2432004pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Owsianik G. The transient receptor potential family of ion channels. Genome Biol. 2011;12(3):218. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra P, Gulyas AI, Miles R. How many subtypes of inhibitory cells in the hippocampus? Neuron. 1998;20(5):983–993. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier AM, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Moqrich A, Earley TJ, Hergarden AC, Story GM, Colley S, Hogenesch JB, McIntyre P, et al. A heat-sensitive TRP channel expressed in keratinocytes. Science. 2002;296(5575):2046–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1073140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Andresen MC. TRPV1 marks synaptic segregation of multiple convergent afferents at the rat medial solitary tract nucleus. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The ligand that came from within. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22(1):17–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente N, Cui Y, Lassalle O, Lafourcade M, Georges F, Venance L, Grandes P, Manzoni OJ. Polymodal activation of the endocannabinoid system in the extended amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(12):1542–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey S, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JC, Davis JB, Benham CD. [3H]Resiniferatoxin autoradiography in the CNS of wild-type and TRPV1 null mice defines TRPV1 (VR-1) protein distribution. Brain Res. 2004;995(2):176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JF, Krause JE, Cortright DN. The distribution and regulation of vanilloid receptor VR1 and VR1 5’ splice variant RNA expression in rat. Neuroscience. 2001;107(3):373–81. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamura T, Sasaki M, Tohda C, Kuraishi Y. Existence of capsaicin-sensitive glutamatergic terminals in rat hypothalamus. Neuroreport. 1998;9(9):2045–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki K, Suzuki M, Mizuno A, Tominaga M. Effects of body temperature on neural activity in the hippocampus: regulation of resting membrane potentials by transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. J Neurosci. 2007;27(7):1566–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4284-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GD, Gunthorpe MJ, Kelsell RE, Hayes PD, Reilly P, Facer P, Wright JE, Jerman JC, Walhin JP, Ooi L, et al. TRPV3 is a temperature-sensitive vanilloid receptor-like protein. Nature. 2002;418(6894):186–90. doi: 10.1038/nature00894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strotmann R, Harteneck C, Nunnenmacher K, Schultz G, Plant TD. OTRPC4, a nonselective cation channel that confers sensitivity to extracellular osmolarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):695–702. doi: 10.1038/35036318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21(3):531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth A, Boczan J, Kedei N, Lizanecz E, Bagi Z, Papp Z, Edes I, Csiba L, Blumberg PM. Expression and distribution of vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) in the adult rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;135(1-2):162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K, Hofmann T, Montell C. Lysosomal localization of TRPML3 depends on TRPML2 and the mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(25):17517–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens J, Appendino G, Nilius B. Pharmacology of vanilloid transient receptor potential cation channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(6):1262–79. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Vriens J, Suh SH, Benham CD, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Heat-evoked activation of TRPV4 channels in a HEK293 cell expression system and in native mouse aorta endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):47044–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigstrom H, Gustafsson B. Facilitated induction of hippocampal long-lasting potentiation during blockade of inhibition. Nature. 1983;301(5901):603–4. doi: 10.1038/301603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigstrom H, Gustafsson B. Facilitation of hippocampal long-lasting potentiation by GABA antagonists. Acta Physiol Scand. 1985;125(1):159–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1985.tb07703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Ramsey IS, Kotecha SA, Moran MM, Chong JA, Lawson D, Ge P, Lilly J, Silos-Santiago I, Xie Y, et al. TRPV3 is a calcium-permeable temperature-sensitive cation channel. Nature. 2002;418(6894):181–6. doi: 10.1038/nature00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Delling M, Jun JC, Clapham DE. Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(5):628–635. doi: 10.1038/nn1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You IJ, Jung YH, Kim MJ, Kwon SH, Hong SI, Lee SY, Jang CG. Alterations in the emotional and memory behavioral phenotypes of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1-deficient mice are mediated by changes in expression of 5-HTA, GABA(A), and NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):1034–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Burrell BD. Endocannabinoid-dependent LTD in a nociceptive synapse requires activation of a presynaptic TRPV-like receptor. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104(5):2766–77. doi: 10.1152/jn.00491.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zschenderlein C, Gebhardt C, von Bohlen Und Halbach O, Kulisch C, Albrecht D. Capsaicin-induced changes in LTP in the lateral amygdala are mediated by TRPV1. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):16116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]