Abstract

Intracardiac metastasis as the initial presentation of malignant neoplasm is very rare. We report here on a 64-year-old man with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) initially presenting with intracardiac metastasis which was identified with 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET). The patient was admitted with complaints of exertional dyspnea and vague chest discomfort that had developed a few weeks ago. Two-dimensional echocardiography revealed a heart mass attached to its akinetic wall in the right ventricular chamber. CT and MRI demonstrated a large tumor involving the epicardium and myocardium in the right ventricle, and there was a mass in the right lower lobe of the lung along with multiple lymphadenopathies. Cytologic examination of the percutaneous needle aspiration of a lymph node in the anterior mediastinum revealed malignant epithelial cell nests, and this was strongly suggestive of squamous cell carcinoma. Subsequent FDG PET confirmed that the intracardiac mass had an abnormally increased FDG uptake, and again this was strongly suggestive of malignancy. By systemically considering these imaging studies, we were able to diagnose the mass as intracardiac metastasis of NSCLC.

Keywords: Cardiac metastasis, Lung cancer, PET

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic disease spreading to the heart is a rare finding that complicates the clinical course of patients with malignant neoplasm. However, autopsy studies have reported the prevalence of secondary cardiac tumors varies from 1.6% to 15.4% for patients with a malignant tumor1-3). In recent years, this presentation appears to be increasing in frequency due not only to better diagnostic technology, but also to more effective treatment modalities that prolong survival and thereby increase the potential of metastasis4, 5). Cardiac metastases almost always occur in the disseminated setting of the primary disease. Therefore, intracardiac metastasis as the initial presentation of a tumor elsewhere in the body is very rare. We report here on a case of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) initially presenting with intracardiac metastasis which was identified with 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET).

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with the chief complaints of exertional dyspnea and vague chest discomfort that had developed a few weeks ago. On review of the symptoms, he also complained of fever and cold sweating that began 7 days before admission. He was an active smoker, and he did not have any allergies or familial medical history. The initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 100/75 mmHg, pulse rate 86 per minute, temperature 38℃, and a respiration rate of 20 per minute. There was no evidence of cervical lymphadenopathy, and there were no abnormal findings on chest and abdomen examination. Electrocardiography (EKG) showed a complete right bundle branch block (RBBB), and chest X-ray revealed a mass-like lesion in the right lower lung. Transthoracic and transesophageal 2-D echocardiography showed a large mass tightly attached to its akinetic apical wall in the right ventricular chamber (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a large tumor having involvement of the epicardium and myocardium in the right ventricle, and there was a mass in the right lower lobe of the lung and multiple lymphadenopathies (Figure 2A, 2B). The cytologic examination of the percutaneous fine needle aspiration of a lymph node in the anterior mediastinum revealed malignant epithelial cell nests that were strongly suggestive of squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 3). Subsequent FDG PET confirmed that the intracardiac mass had an abnormally increased FDG uptake, which was strongly suggestive of malignancy (Figure 2C). Although there was no histologic confirmation, we diagnosed the heart mass as intracardiac metastasis by systematically considering these imaging studies. We discussed the treatment options with the patient and his family, such as surgical resection with histologic confirmation for the intracardiac tumor followed by palliative chemotherapy, or whether to perform palliative chemotherapy alone. Thereafter, we administered palliative chemotherapy with the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin in consideration of the absence of right ventricular outflow obstruction and patient's preference.

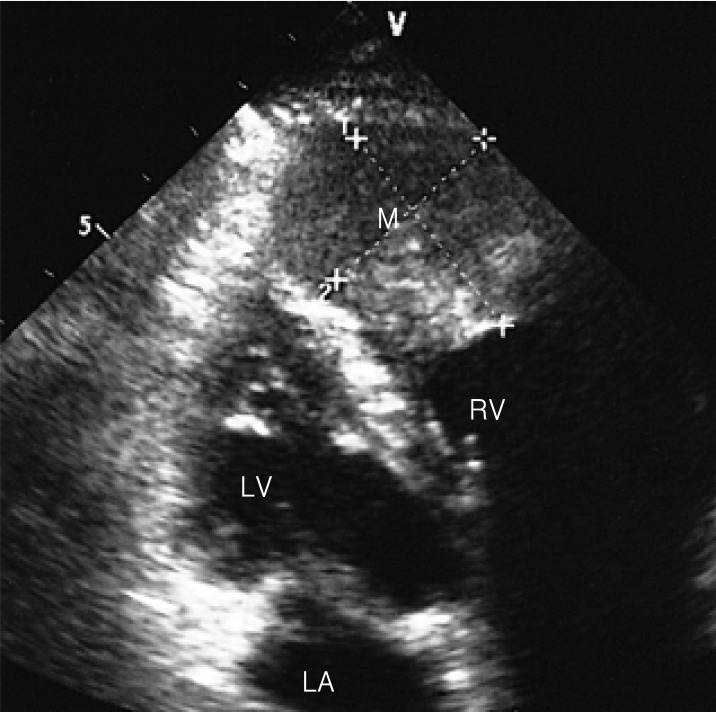

Figure 1.

Transthoracic 2-D echocardiography shows about a 3×4 cm-sized mass attached to its apical wall in the right ventricular chamber. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; M, mass; RV, right ventricle.

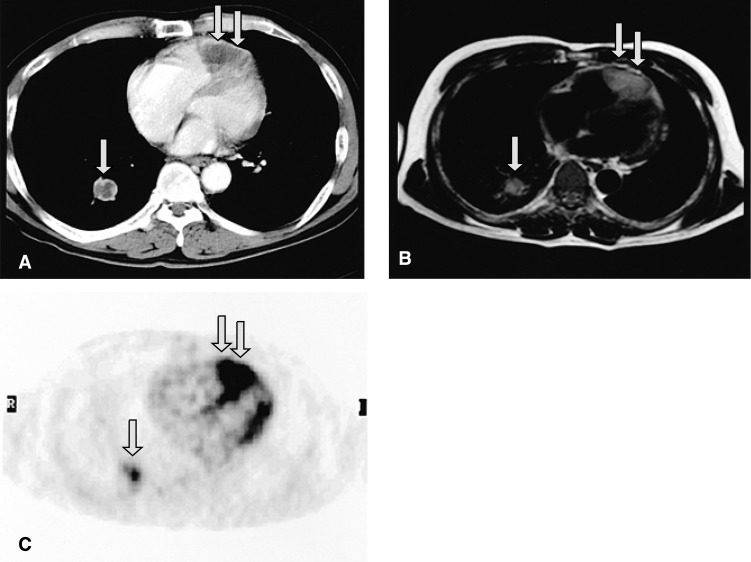

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT (A) and T1-weighted MRI (B) show a large intracardiac mass involving the pericardium and myocardium in the right ventricle (double arrows), and a mass in the right lower lobe of the lung (single arrows). 18F-FDG PET (C) demonstrates that the intracardiac tumor had an intensely increased FDG uptake (double arrows), which is strongly suggestive of malignancy.

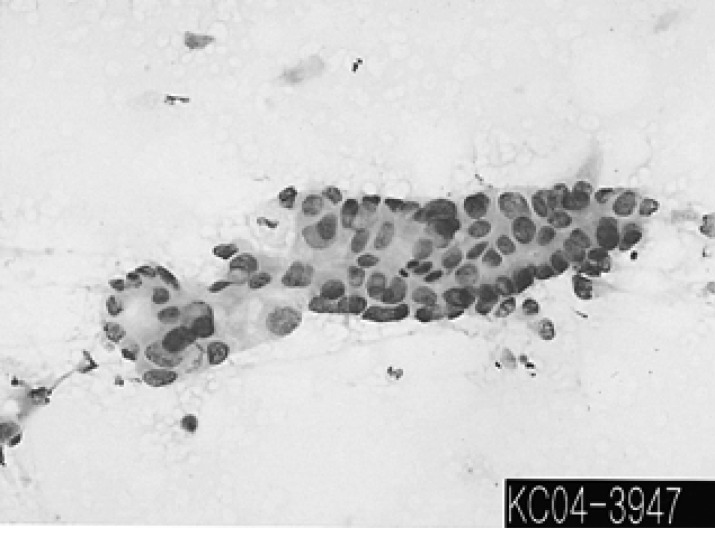

Figure 3.

The cytologic examination of US-guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration reveals malignant epithelial cell nests, and this was strongly suggestive of squamous cell carcinoma. (Papanicolaou smear, ×200)

DISCUSSION

Primary cardiac tumors are rare. However, when they are found and diagnosed, most cases are known to be histologically benign, with the most common tumor type in all age groups being myxoma5). In the heart, metastatic tumors are many times more common than the primary tumors5). As the overall survival of patients having various malignant tumors is prolonged by more effective therapy, it seems that the frequency of cardiac metastases has also increased4, 5). Tumors with a high tendency of metastasis to the heart are malignant melanoma, leukemia, lymphoma and malignant germ cell tumors3, 6). In absolute numbers, however, the most common primary tumors of cardiac metastases are carcinoma of the lung and breast, and this reflects the high incidence of these malignancies3, 7). Tumor cells reach the heart and pericardium by one of four pathways: retrograde lymphatic extension, hematogenous spread, direct contiguous extension or transvenous extension.

Cardiac metastases almost always occur in the setting of disseminated primary disease. As is the case for our patient, a cardiac metastasis may be the initial presentation of a tumor elsewhere in the body. Although the cardiac metastases may present with a large number of nonspecific signs and symptoms, the most common symptoms are dyspnea, chest discomfort, a rapid increase in the heart size on chest x-ray, a new onset of tachycardia/arrhythmia or atrioventricular block and congestive heart failure7). Our patient presented with dyspnea and chest discomfort. The EKG revealed complete RBBB with an unknown onset, which might have resulted from the intracardic tumor of the right ventricle.

Metastatic cancer to the heart is not easy to diagnose ante-mortem. 2-D echocardiography may be useful for the visualization of intracardiac tumor at the earlier stage8). CT and MRI may provide an additional anatomic delineation7, 9, 10). MRI especially offers excellent contrast resolution, unlike 2-D echocardiography or CT, and this allows for the clinical distinction between tumor and myocardium7). Most cardiac tumors display low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and they are brighter on T2-weighted images, showing enhancement after administration of contrast material11). However, because the signal intensity of a thrombus on MRI varies according to its age, the differential diagnosis between intracardiac tumor and organized thrombi may be somewhat difficult7, 12). In our case, 2-D echocardiography detected a large mass attached to its akinetic wall in the right ventricular chamber, and the CT scan showed an intracardiac tumor involving the epicardium and myocardium of the right ventricle. MRI revealed that the intracardiac tumor had low signal intensity on the T1-weighted images, and it had a little bit brighter signal on the T2-weight images. Still, the differentiation of intracardiac malignancy from organized thrombus was not yet definite. FDG PET has been useful in the diagnosis and staging of various malignancies. Because of its high sensitivity, it is frequently able to detect malignant lesions that are not clearly identified by anatomic imaging techniques. Although the role of FDG PET in cardiac metastasis remains to be validated, it has recently been shown to be useful for detecting cardiac metastasis and differentiating this from thrombus, myxoma or benign scar tissue12-15). We performed FDG PET to demonstrate that the intracardiac mass had significant metabolic activity, which is atypical for thrombus and more characteristic of a tumor. Although we did not perform a myocardial biopsy for the histologic confirmation, we were able identify the mass as intracardiac metastasis rather than an organized thrombus by systematically considering all the radiographic findings. In view of the fact that the intracardiac tumor involved the epicardium and myocardium of the right ventricle, and metastatic disease was also detected in a lymph node in the anterior mediastinum, the retrograde spread of tumor through lymphatic channels in the mediastinum was thought to be the pathway of the cardiac metastasis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing a patient with NSCLC initially presented with intracardiac metastasis which was diagnosed this with FDG PET.

A standard treatment modality for cardiac metastases has not yet been established. Because most patients with cardiac metastases have disseminated disease, the therapy generally consists of treatment for the primary tumor or palliative care. Despite the poor prognosis for patients with cardiac metastasis, however, surgical treatment should be considered when important symptoms of obstruction outweigh the mortality risk of operating and the benefit of medical therapy alone. Especially for the isolated intracardiac tumor with no evidence of widespread disease, surgical resection seems to be safe and relieve the symptoms, and it would very likely prolong the life span of the patient16). For our patient, we initially made a choice of palliative chemotherapy in consideration of the absence of obstructive symptoms and the patient's preference.

In summary, we report here on a case of NSCLC that initially presented with intracardiac metastasis which was identified with FDG PET. Although the role of FDG PET for cardiac metastasis remains to be well defined, it seems to be a useful modality for noninvasively differentiating intracardiac metastasis from an organized thrombus.

References

- 1.Pollia JA, Gogol LJ. Some notes on malignancies of the heart. Am J Cancer. 1936;27:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukai K, Shinkai T, Tominaga K, Shimosato Y. The incidence of secondary tumors of the heart and pericardium: a 10-year study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1988;18:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klatt EC, Heittz DR. Cardiac metastases. Cancer. 1990;65:1456–1459. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900315)65:6<1456::aid-cncr2820650634>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parravicini R, Fahim NA, Cocconcelli F, Barchetti M, Nafeh M, Benassi A, Grisendi A, Garuti W, Benimeo A. Cardiac metastasis of rectal adenocarcinoma: surgical treatment. Tex Heart Inst J. 1993;20:296–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefka J, Cleveland JC, Lucia MS, Singh M. Sarcomatoid intracardiac metastasis of a testicular germ cell tumor closely resembling primary cardiac sarcoma. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1074–1077. doi: 10.1053/s0046-8177(03)00415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiala W, Schneider J. Heart metastasis of malignant tumors: an autopsy study. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1982;112:1497–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiles C, Woodard PK, Gutierrez FR, Link KM. Metastatic involvement of the heart and pericardium: CT and MR imaging. Radiographics. 2001;21:439–449. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr15439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weg IL, Mehra S, Azueta V, Rosner F. Cardiac metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the lung: echocardiographic-pathologic correlation. Am J Med. 1986;80:108–112. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shih TT, Su CT, Yang PC, Hsu JC, Huang KM. Diagnosis of cardiac metastasis by computed tomography: report of 5 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990;89:392–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majano-Lainez RA. Cardiac tumors: a current clinical and pathological perspective. Crit Rev Oncog. 1997;8:293–303. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujita N, Caputo CR, Higgins CB. Diagnosis and characterization of intracardiac masses by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Card Imaging. 1994;8:69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimotsu Y, Ishida Y, Fukuchi K, Hayashida K, Toba M, Hamada S, Takamiya M, Satoh T, Nakanishi N, Nishimura T. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET identification of cardiac metastasis arising from uterine cervical carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:2084–2087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghesani NV, Sun X, Zhuang H, Sam JW, Alavi A. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography excludes pericardial metastasis by recurrent lung cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28:666–667. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000079392.85361.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plutchok JJ, Boxt LM, Weinberger J, Fawwaz R, Sherman WH, van Heertum RL. Differentiation of cardiac tumor from thrombus by combined MRI and F-18 FDG PET imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 1998;23:324–325. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199805000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agostini D, Babatasi G, Galateau F, Grollier G, Potier JC, Bouvard G. Detection of cardiac myxoma by F-18 FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 1999;24:159–160. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy MC, Sweeney MS, Putnam JB, Jr, Walker WE, Frazier OH, Ott DA, Cooley DA. Surgical treatment of cardiac tumors: a 25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49:612–618. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(90)90310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]