Abstract

Objective

To examine the effects of patient adherence on outcome from exposure and response prevention (EX/RP) therapy in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Method

Thirty adults with OCD were randomized to EX/RP (n=15) or EX/RP augmented by motivational interviewing strategies (n=15). Both treatments included three introductory sessions and 15 exposure sessions. Because there were no significant group differences in adherence or outcome, the groups were combined to examine the effects of patient adherence on outcome. Independent evaluators assessed OCD severity using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Therapists assessed patient adherence to EX/RP assignments at each session using the Patient EX/RP Adherence Scale (PEAS). Linear regression models examined the effects of PEAS scores on outcome, adjusting for baseline severity. The relationship between patient adherence and other predictors of outcome was explored using structural equation modeling.

Results

Higher average PEAS ratings significantly predicted lower post-treatment OCD severity in ITT and completer samples. PEAS ratings in early sessions (5–9) also significantly predicted post-treatment OCD severity. The effects of other significant predictors of outcome in this sample (baseline OCD severity, hoarding subtype, and working alliance) were fully mediated by patient adherence.

Conclusions

Patient adherence to between-session EX/RP assignments significantly predicted treatment outcome, as did early patient adherence and change in early adherence. Patient adherence mediated the effects of other predictors of outcome. Future research should develop interventions that increase adherence and then test whether increasing adherence improves outcome. If effective, these interventions could then be used to personalize care.

Keywords: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, exposure and response prevention, cognitive behavioral therapy, treatment predictors, treatment compliance

Cognitive-behavioral therapy consisting of exposure and response prevention (EX/RP) is an effective treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; American Psychiatric Association, 2007). However, only about half of patients who receive EX/RP achieve minimal symptoms (Simpson, et al., 2008; Simpson, Huppert, Petkova, Foa, & Liebowitz, 2006). Treatment outcome might be improved by developing more personalized care (Insel, 2009). One approach to personalized care is to identify factors that interfere with EX/RP outcome, develop interventions to address these factors, and provide these interventions to the individuals who need them.

One factor thought to affect EX/RP outcome is whether patients adhere to the treatment procedures. Specifically, EX/RP therapists help patients face feared situations (“exposures”) to promote habituation to the anxiety that these situations trigger. Patients are asked to refrain from avoidance behaviors and rituals (“response prevention”) in order to break the connection between rituals and anxiety relief. Together, these procedures help disconfirm patients’ irrational beliefs. Therapists practice these steps with patients in session and assign specific exercises for between-session practice. Adherence with between-session assignments is thought to be critical for good outcome because repeated practice in different contexts is theorized to be essential to the emotional processing of the fear structure (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Kozak & Foa, 1997).

Some studies suggest that patient adherence to EX/RP procedures is associated with treatment outcome (Abramowitz, Franklin, Zoellner, & DiBernardo, 2002; De Araujo, Ito, & Marks, 1996; Tolin, Maltby, Diefenbach, Hannan, & Worhunsky, 2004). However, Woods, Chambless, and Steketee (2002) found no significant relationship between EX/RP outcome and patient homework adherence. Unfortunately, patient adherence was assessed differently across these studies, none of the adherence measures has demonstrated validity or reliability, and some studies did not measure patient adherence prospectively. Thus, the effect of patient EX/RP adherence on treatment outcome has yet to be adequately examined.

To address this significant gap, the current study examined the relationship between patient adherence to between-session assignments and treatment outcome in 30 adults with OCD who received EX/RP as part of a clinical trial. We used the Patient EX/RP Adherence Scale (PEAS) to prospectively assess adherence with between-session assignments because of its excellent inter-rater reliability and good construct validity (Simpson, Maher, et al., 2010). We hypothesized that patient adherence to between-session EX/RP assignments would be inversely associated with post-treatment OCD severity. We also examined whether early patient adherence predicted post-treatment OCD severity. Finally, we explored the relationship between patient adherence and other variables that predicted outcome in this sample.

Method

Overview of Study Design

This study was conducted at the Anxiety Disorders Clinic at the New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University and approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written consent. The study design and procedures are described in detail elsewhere (Simpson, Zuckoff, et al., 2010). Briefly, 30 adults with OCD were randomly assigned to standard EX/RP (n=15) or EX/RP augmented by motivational interviewing (MI) strategies (EX/RP+MI; n=15). Both treatments followed standard EX/RP procedures outlined by Kozak and Foa (1997) and included three introductory sessions, 15 twice weekly 90-minute exposure sessions, and daily homework assignments. There were neither statistical nor clinically meaningful differences in patient adherence or treatment outcome between the EX/RP and EX/RP+MI groups, and therapist adherence to EX/RP procedures was excellent in both conditions (for details, see Simpson, Zuckoff, et al., 2010). Because the mean difference in patient adherence (0.13; 95% confidence interval: −1.07, +1.33) and in treatment outcome (0.133, 95% CI: −6.91, 7.18) between the two groups was very small and there was no significant group by adherence interaction (p=0.46), the groups were combined for the purposes of this study.

Participants

Patients were eligible if they were between 18 and 70 years old and had a principal DSM-IV diagnosis of OCD with a Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score of at least 16. Patients could be on psychotropic medication if they were on a stable dose for at least 12 weeks and if the dose remained stable during the study. Patients were excluded for other psychiatric problems needing immediate treatment (e.g., mania, psychosis, suicidality), an unstable medical condition, or prior EX/RP treatment (≥ 8 sessions/two months). Psychiatric diagnoses were determined by an M.D. or Ph.D. and confirmed by an independent rater using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996).

Assessments

Independent evaluators blind to treatment condition assessed patients at baseline, and after sessions 3, 11, and 18. OCD severity was assessed using the Y-BOCS (Goodman, et al., 1989), clinical response using the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-Improvement; Guy, 1976), and symptoms of depression using the 17-item HAM-D (Hamilton, 1960).

Therapists evaluated patient adherence to between-session EX/RP assignments at the start of each exposure session (sessions 5–18) using the Patient EX/RP Adherence Scale (PEAS; Simpson, Maher, et al., 2010). The PEAS consists of three items that are averaged: 1) the quantity of exposures attempted (% of exposures attempted of those assigned); 2) the quality of exposures attempted (how well the patient did the attempted exposures); and 3) the degree of ritual prevention (% of urges to ritualize that patient successfully resisted). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale with anchors; higher ratings indicate better adherence. The PEAS has excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC ≥ 0.97) and good construct validity.

Other characteristics found to predict EX/RP outcome (reviewed in Maher, et al., 2010) were also assessed at baseline. These included: degree of insight (using the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale, BABS; Eisen, et al., 1998), quality of life (using the Quality of Life and Enjoyment Questionnaire or Q-LES-Q; Endicott, Nee, Harrison, & Blumenthal, 1993), Axis I comorbidity, number of SRI trials, female gender, employment status, and hoarding subtype (i.e., primary hoarding obsessions and compulsions on the Y-BOCS checklist). After the third introductory session, patients completed the Expectancy Questionnaire (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000) and Working Alliance Inventory-Self Report (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989).

Statistical Analyses

Linear regression was used to evaluate whether patient adherence (i.e., mean total PEAS score across all exposure sessions) predicted post-treatment OCD severity (i.e., Y-BOCS score) adjusting for pre-treatment severity. The analyses were conducted for the intent-to-treat sample ([ITT], N=30) and for patients who completed EX/RP treatment (N=25). For the ITT sample, the last available observation for the outcome variable was used; missing sessions after a patient dropped from the study were given a PEAS rating of 1 (the worst score). Sensitivity analyses explored the robustness of these results (see Supplementary Materials). To confirm that our findings were not limited to the Y-BOCS, we used logistic regression to examine whether the mean total PEAS score predicted a CGI-Improvement rating of much or very much improved.

Linear regression was also used to explore whether early adherence predicted outcome. The model was first constructed using the mean PEAS ratings from all sessions (sessions 5–18) adjusting for baseline severity. Then the PEAS ratings from the latter sessions (starting with session 18) were removed sequentially to determine the minimum number of sessions needed for PEAS ratings to predict outcome. In the ITT and completer samples, the minimum sequence was sessions 5–9. Thus, a linear model was constructed using the mean PEAS ratings from sessions 5–9 to explore the association between early adherence and post-treatment OCD severity. As a final step, the model included change in early adherence as an additional independent variable.

Univariate linear regression models were used to explore what predicted outcome in this sample (other than patient adherence), and a stepwise regression was conducted to establish the strongest predictors. Structural equation modeling (SEM, Preacher & Hayes, 2004) was then used to examine the relationship between these other predictors of outcome and patient mean adherence and to estimate mediated effects.

All statistical tests were conducted at two-sided level of significance α=.05.

Results

Sample

Thirty adults with OCD entered and received EX/RP treatment. Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Five patients dropped out (at session 4 [EX/RP] and at sessions 5, 9, 11, and 15 [EX/RP+MI]). The observed mean total PEAS rating was 5.17 (SD = 0.93, range 3.22–6.40). Patient outcome varied: 63.3 % had at least a 25% reduction in Y-BOCS score after EX/RP, and 36.7% had an excellent response (i.e., a Y-BOCS score ≤ 12).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Sample (N=30)

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 39.9 (13.4) |

| Female, No. (%) | 14 (47) |

| Caucasian, No. (%) | 19 (63) |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | |

| Single | 23 (77) |

| Married-Partnered | 6 (20) |

| Divorced-Separated | 1 (3) |

| Education, y, mean (SD) | 16.1 (2.1) |

| Employment: working or school at least part-time, No. (%) | 18 (60) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Y-BOCS at baseline (N=30), mean (SD; range) | 28.1 (4.2; 22 to 37) |

| Y-BOCS at study end (N = 25), mean (SD; range) | 13.8 (7.8; 0 to 29) |

| HAM-D at baseline, mean (SD) | 8.2 (5.2) |

| Age of OCD Onset, y, mean (SD) | 20.5 (10.0) |

| Duration of OCD, y, mean (SD) | 18.5 (11.9) |

| Hoarding subtype, No. (%)1 | 4 (13) |

| Current Axis I diagnoses, No. (%): | |

| OCD only | 15 (50) |

| Depressive Disorder (MDD/dysthymia/NOS) | 9 (30) |

| Other Anxiety Disorder | 12 (40) |

| Currently taking SRI medication, No. (%) | 11 (37) |

| Weeks on current SRI, mean (SD) | 89 (81) |

| Currently taking non-SRI medication:2 | |

| with an SRI, No. (%) | 4 (13) |

| without an SRI, No. (%) | 1 (3) |

| History of SRI medication, No. (%) | 14 (47) |

| History of Prior Exposure Sessions, No. (%) | 4 (13) |

Note. HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Scale; No., Number; OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; SRI, Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; y, year.

Patients were considered to have hoarding subtype if their primary obsessions and compulsions on the Y-BOCS checklist were related to hoarding.

Four patients were receiving a non-SRI medication (benzodiazepine, n=2; buproprion, n=2), and one was receiving only a benzodiazepine, each for more than five months.

The effect of total mean patient adherence on post-treatment OCD severity

Patient adherence to between-session EX/RP assignments significantly predicted post-treatment OCD severity. As shown in Table 2, higher PEAS scores predicted lower post-treatment Y-BOCS scores in the ITT and completer samples after adjusting for baseline severity, explaining a large portion of the variance. A one unit improvement in mean PEAS adherence led to an additional 4.3-point (ITT sample) or 6.5-point (completer sample) Y-BOCS decrease, both clinically meaningful changes. Sensitivity analyses confirmed this relationship between patient homework adherence and post-treatment OCD severity (see Supplementary Materials).

Table 2.

The Association between Total Mean Adherence and Post-treatment OCD Severity

| Sample | Predictors | β | 95% CI | p value | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intent-to-Treat | |||||

| Baseline Y-BOCS | 0.35 | (−0.21, 0.90) | .209 | .02 | |

| Total mean adherence | −4.28 | (−5.77, −2.80) | <.001 | .46 | |

| Completer | |||||

| Baseline Y-BOCS | 0.19 | (−0.42, 0.81) | .523 | .01 | |

| Total mean adherence | −6.48 | (−9.23, −3.72) | <.001 | .49 | |

Note. CI, confidence interval; sr2, the semi-partial correlation is a measure of the unique variance explained by each predictor and it is equivalent to the R2 change in a step-wise model when each predictor is entered separately; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score.

To achieve minimal symptoms after treatment (i.e., a Y-BOCS score of ≤ 12), patients had to achieve a high degree of adherence. Based on the linear regression model, completers had to achieve a mean PEAS rating of 5.6 (95% CI for forecasting a future PEAS rating: 3.9, 7.3). In our sample, patients who completed treatment with Y-BOCS scores this low had an observed mean PEAS ratings of 5.92 (SD=0.31; range 5.43 to 6.40). A PEAS score of 5 on all items (“good”) requires attempting assigned exposures and resisting urges to ritualize about 75% of the time and completing attempted exposures with minimal safety aids. A score of 6 (“very good”) signifies attempting assigned exposures and resisting urges to ritualize >90% of the time and completing assigned exposures as instructed.

Mean PEAS scores also significantly predicted whether a patient was rated as a responder on the CGI-Improvement scale (i.e., much or very much improved): a one unit PEAS change increased the odds of response by a factor of 3.29 (95% CI [1.34, 8.11], p=.009) in the ITT sample and by a factor of 7.37 (95% CI [1.51, 35.88], p=.013) among completers.

The effect of early adherence on post-treatment OCD severity

Higher mean PEAS scores during sessions 5–9 predicted lower post-treatment Y-BOCS scores after adjusting for baseline severity (ITT: Beta=−4.15, 95% CI [−2.22, −6.08], p <.001; sr2=.34; Completers: Beta=−4.05, 95% CI [−0.49, −7.62], p=.028; sr2=.19). As shown in Table 3, mean PEAS and change in PEAS ratings during sessions 5–9 each independently predicted post-treatment Y-BOCS scores and together accounted for a large portion of the variance in outcome.

Table 3.

The Association between Early Adherence and Post-treatment OCD Severity

| Sample | Predictors | β | 95% CI | p value | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intent-to-treat | |||||

| Baseline Y-BOCS | 0.33 | (−0.24, 0.91) | .246 | .02 | |

| Early mean adherence | −3.82 | (−5.56, −2.08) | <.001 | .29 | |

| Early change of adherence | −3.16* | (−5.45,−0.87) | .009 | .11 | |

| Completer | |||||

| Baseline Y-BOCS | 0.36 | (−0.40, 1.12) | .340 | .03 | |

| Early mean adherence | −4.17 | (−7.49, −0.85) | .016 | .20 | |

| Early change of adherence | −3.58* | (−7.07, −0.09) | .045 | .13 | |

Note. CI, confidence interval; sr2, the semi-partial correlation is a measure of the unique variance explained by each predictor and it is equivalent to the R2 change in a step-wise model when each predictor is entered separately; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score.

Standardized coefficient of early change of adherence, i.e., 1 sd unit increase of early change of adherence corresponds to β points change in post-treatment Y-BOCS.

The relationship between patient adherence and other predictors of outcome

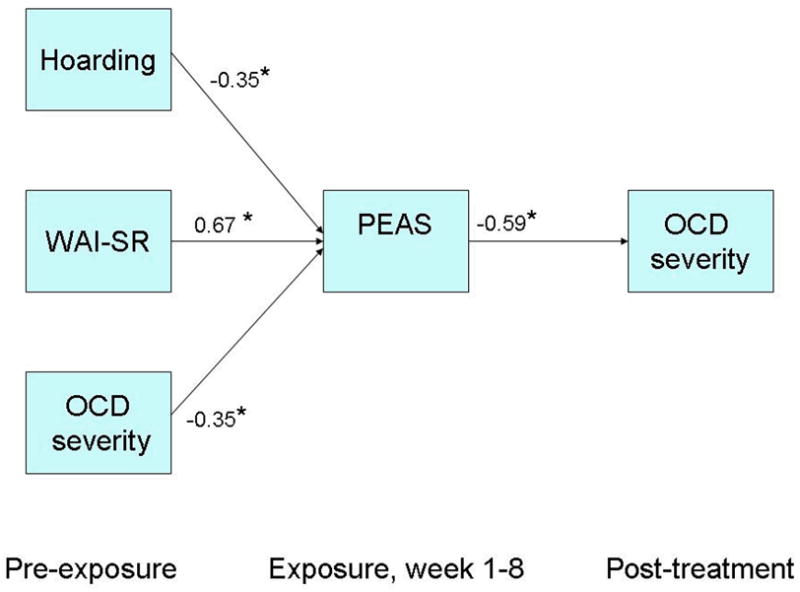

In univariate models, three variables besides patient adherence significantly predicted post-treatment Y-BOCS scores after adjusting for baseline severity: hoarding subtype (p=.024), working alliance (p=.001), and treatment expectancy (p=.014). Other baseline characteristics did not: degree of insight (p=.331); depressive severity (p=.111); quality of life (p=.683); total number of SRI trials (p=.456); total number of Axis I comorbid conditions (p=.595); female gender (p=.895); and being employed (p=.115). In the final model, hoarding subtype (p=.043) and working alliance (p=.002) remained significant after adjusting for baseline OCD severity, which was also significant (p=.007). The effects of each were fully mediated by patient adherence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model for Predictors of Post-treatment OCD Severity being Mediated by Patient Adherence

*p<.01, Parameters for fully saturated model: Model Chi-square = 62.37 (7), p<.01. R-square for Post-treatment OCD severity = .62; R-square for mediator (PEAS) = .72. Direct effects of predictors on post-treatment OCD severity are not significant, demonstrating full mediation by PEAS. Indirect effects of predictors through mediator (PEAS) on post-treatment OCD severity: Hoarding subtype (0.21, p=.03), WAI-SR (-0.40, p=.01), baseline OCD severity (0.21, p=.03). Note: OCD, Obsessive compulsive disorder; PEAS, Patient EX/RP Adherence Scale; WAI-SR, Working Alliance Inventory – Self Report.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between patient adherence to between-session EX/RP assignments and EX/RP outcome using a valid and reliable adherence measure in adults with OCD. As hypothesized, patient adherence significantly predicted post-treatment OCD severity. Moreover, the degree of patient adherence was significantly associated with the degree of improvement and the odds of response. In addition, early patient adherence and change in early patient adherence each significantly predicted post-treatment OCD severity. Patient adherence fully mediated the effects of other significant predictors on outcome.

Our findings are consistent with prior research (Abramowitz, et al., 2002; De Araujo, et al., 1996; de Haan, et al., 1997; Tolin, et al., 2004) and advance the literature in several important ways. First, unlike the prior studies, we used a patient adherence scale with demonstrated reliability and validity and measured patient adherence prospectively at each exposure session. Because dismantling studies found that exposures and ritual prevention are each key to good outcome (Foa, Steketee, Grayson, Turner, & Latimer, 1984), the scale focuses on the quantity and quality of patient adherence to these essential EX/RP procedures. Such focus may be key to revealing the relationship between patient adherence and treatment outcome. Second, our data indicate that it is important for patients to achieve better than good homework adherence across all exposure sessions: only these patients are likely to achieve minimal symptoms. Third, we found that not only mean adherence but also early adherence (both mean early adherence and change in early adherence) affect treatment outcome. Finally, patient adherence fully mediated other predictors of outcome in this sample. If true in other samples, this may explain why OCD predictor studies often have found small or inconsistent effects on treatment outcome: study samples vary in patient characteristics, different patient characteristics can affect patient adherence, and patient adherence--although rarely measured--may be one of the strongest predictors of outcome and mediate other predictors’ effects.

These findings have clinical implications. Consistent with other studies (Maher, et al., 2010), the data suggest that patients with severe OCD symptoms need not be excluded from EX/RP as practice guidelines suggest (American Psychiatric Association, 2007). Instead, therapists should carefully monitor patient adherence with between-session assignments to ascertain who is likely to have a good response. If the link between patient adherence and treatment outcome is proven to be causal, then interventions that improve patient adherence should be provided to those with poor early adherence, and this should lead to better treatment outcome. Such therapeutic tailoring is consistent with a personalized care model.

The study has several limitations. The sample size and number of therapists was small, and the study was designed for other purposes. Thus, replication is warranted. We suspect that when EX/RP is delivered in a weekly format (as it is by most community providers), the effects of between-session patient adherence on OCD outcome might be even more robust. Second, like many studies of patient adherence, there is the potential confound between patient adherence and treatment outcome measures. Thus, we conducted sensitivity analyses, which yielded similar findings, and examined early adherence, where this confound is not present. Third, therapists rated patient adherence using patients’ self-report. A subset of sessions were reviewed by independent raters as part of another study, and reliability was excellent (Simpson, Maher, et al., 2010). However, self-reports are subject to patient recall.

In summary, patient adherence to between-session EX/RP assignments significantly predicted treatment outcome, as did early patient adherence and change in early adherence. Patient adherence mediated the effects of other predictors of outcome. Future studies should establish that the link between patient adherence and treatment outcome is causal and develop interventions to improve adherence. These interventions could then be used to personalize care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (R34 MH071570) and by a 2005 NARSAD Young Investigator Award to Dr. Simpson. We thank Stephen and Constance Lieber for supporting the first author as a NARSAD Lieber Investigator. We thank members of the Anxiety Disorders Clinic for help with the conduct of this trial and comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We also thank Shawn Cahill for helping with EX/RP supervision and Naihua Duan and Melanie Wall for consulting on the statistical plan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp

Contributor Information

Helen Blair Simpson, Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University.

Michael J. Maher, Anxiety Disorders Clinic, New York State Psychiatric Institute

Yuanjia Wang, Department of Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Yuanyuan Bao, Division of Epidemiology, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Edna B. Foa, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Martin Franklin, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Zoellner LA, DiBernardo CL. Treatment compliance and outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:447–463. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Araujo LA, Ito LM, Marks IM. Early compliance and other factors predicting outcome of exposure for obsessive-compulsive disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;169:747–752. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.6.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan E, van Oppen P, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin KA, Van Dyck R. Prediction of outcome and early vs. late improvement in OCD patients treated with cognitive behaviour therapy and pharmacotherapy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1997;96:354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, Atala KD, Rasmussen SA. The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: reliability and validity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:102–108. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Steketee G, Grayson JB, Turner RM, Latimer PR. Deliberate exposure and blocking of obsessive-compulsive rituals: Immediate and long-term effects. Behavior Therapy. 1984;15:450–472. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A Rating Scale for Depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak MJ, Foa EB. Mastery of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A cognitive-behavioral approach. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Maher MJ, Huppert JD, Chen H, Duan N, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, et al. Moderators and predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:2013–2023. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Ledley DR, Huppert JD, Cahill S, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for augmenting pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:621–630. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Huppert JD, Petkova E, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR. Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:269–276. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Maher M, Page JR, Gibbons CJ, Franklin ME, Foa EB. Development of a patient adherence scale for exposure and response prevention therapy. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Zuckoff AM, Maher MJ, Page JR, Franklin ME, Foa EB, et al. Challenges using motivational interviewing as an adjunct to exposure therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Hannan SE, Worhunsky P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication nonresponders with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a wait-list-controlled open trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:922–931. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CM, Chambless DL, Steketee G. Homework compliance and behavior therapy outcome for panic with agoraphobia and obsessive compulsive disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2002;31:88–95. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.