Summary

Background:

Thrombus resolution is a complex process that involves thrombosis, leukocyte-mediated thrombolysis, and the final resolution of inflammation. Activated Protein C (APC) is an anticoagulant that also possesses immunoregulatory activities.

Objective:

In this study, we sought to examine the effects of APC administration on thrombus resolution using a mouse model of deep vein thrombosis by ligating the inferior vena cava (IVC).

Methods:

The IVCs of C57BL/6 mice were ligated. Beginning on Day 4 post-IVC ligation, mice were injected i.p. daily with APC, APC plus a heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) inhibitor Sn-protoporphyrin IX (SnPP), SnPP alone, or vehicle control. At different time points following surgery, the thrombus-containing IVCs were weighed and then analyzed by biochemical assays and histology.

Results:

Venous thrombi reached maximum size on Day 4 post ligation. The APC-treated group exhibited a significant reduction in thrombus weights on Day 12 but not on Day 7 as compared to control mice. The enhanced thrombus resolution in APC-treated mice correlated with an increased HO-1 expression and a reduced interleukin-6 production. No significant difference was found in urokinase-type plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 between APC-treated and control mice. Co-injection of an HO-1 inhibitor SnPP abolished the ability of APC to enhance thrombus resolution.

Conclusions:

Our data show that APC enhances the resolution of existing venous thrombi via a mechanism that is in part dependent on HO-1, suggesting that APC could be used as a potential treatment for patients with deep vein thrombosis to accelerate thrombus resolution.

Keywords: Protein C, Venous Thrombosis, Heme oxygenase-1, Inflammation, Thrombolytic Therapy

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a condition that affects 1 in 1000 adults [1]. Common complications associated with DVT include both acute events, such as pulmonary embolism, and chronic diseases, such as post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) [1,2]. The underlying pathophysiology of PTS is attributed to venous fibrosis, decreased vein compliance, and inflammation-induced valvular damage [3]. Enhancement of thrombus resolution and suppression of late phase inflammation have been shown to decrease the occurrence of PTS [1-3]. Current treatments for DVT primarily focus on preventing further clot expansion with anticoagulants, such as heparin, thrombin inhibitors, and Xa inhibitor, which are often associated with severe bleeding [4], and on increasing venous blood flow by physical methods, such as elastic compression stockings [1,2]. In addition, vasoactive drugs have also been used to reduce the incidence of PTS [1,2]. However, these therapies are not effective at resolving the existing thrombi. Therefore, developing new strategies that could enhance the resolution of pre-existing thrombi would be clinically beneficial to DVT patients.

During the early phase of thrombus resolution, inflammation leads to an influx of neutrophils and macrophages into the venous thrombi [5]. These inflammatory cells enhance the proteolytic degradation of the thrombi by producing various proteases, including the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)−2 and −9 [5,6]. Once the venous thrombi are removed, the inflammation within the vessel wall needs to be resolved as well. Persistent inflammation during the late stage of thrombus resolution has been shown to contribute to the development of PTS [7]. Indeed, a recent study reported that neutralization of interleukin (IL)-6, which was produced at a high level within the venous thrombi, can significantly decrease collagen deposition and reduce fibrosis in response to DVT [7].

Activated Protein C (APC) is a serine protease that degrades two key coagulation factors, activated Factor V and activated Factor VIII, thus shutting down the blood coagulation cascade [8]. APC also promotes fibrinolysis by decreasing PAI-1 activity [9]. In addition, APC possesses potent cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory activities [10-12]. In this study, we examined the role of APC in venous thrombus resolution by administering APC to mice with existing venous thrombi. We found that APC treatment did not affect the early-phase thrombus resolution. Instead, our results showed that APC significantly reduced the thrombus weight at late-stage thrombus resolution. Mechanistically, we found that administration of APC enhanced heme oxygenase (HO-1) expression and reduced IL-6 production within the venous thrombi. Most importantly, we found that inhibition of HO-1 activity in mice abolished the ability of APC to enhance thrombus resolution. Together, this study identified a novel HO-1-dependent mechanism for APC-mediated enhancement of thrombus resolution. This work also provides a proof of concept for therapeutic use of APC to accelerate thrombus resolution and thus decrease post-thrombotic syndrome in patients with DVT.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human APC (Xigris) was purchased from Canada Pharmacy. Sn-protoporphyrin IX (SnPP) was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences. Goat anti-β-actin antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz; sheep anti-PAI-1 antibody was obtained from American Diagnostica; rabbit anti-HO-1 antibody was obtained from Abcam; and rat-anti-Mac-2 (Galectin-3) antibody was obtained from Cedarlane.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). All mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility and all procedures were performed in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

Surgical model

C57BL/6 mice (8-12 weeks old; body weights 20-30 g) were anesthetized with isoflurane and underwent laparotomy. The inferior vena cava (IVC) was dissected and then ligated with 7-0 silk suture just below the renal veins, based on our published method [6]. The side branches of the IVCs were cauterized. The abdomen was closed with 4-0 vicryl suture and the skin incision was sutured with 4-0 proline suture. Beginning on Day 4 post-surgery, mice were injected i.p. daily with APC (0.5mg/kg body weight), APC plus SnPP (20 mg/kg body weight), SnPP alone, or vehicle control (normal saline). At different time points following surgery, mice were euthanized and the thrombus-containing IVCs were carefully dissected from connective tissues and weighed. After weighing, the thrombosed IVCs were fixed with formalin for histology or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for protein analysis.

Isolation and treatment of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were prepared using our published procedures [11]. Briefly, femur and tibia from C57BL/6 mice were flushed with DMEM containing 10% FBS using a 5 ml syringe and a 25 gauge needle. Isolated cells were centrifuged at 1,000×g and resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 20% L929 cell conditioned media and plated on 6-well tissue culture plates (Corning Inc., NY, US). The media were changed on day 3 and 5. On Day 7, the adherent cells were collected and used as macrophages. To induce HO-1 expression, bone marrow-derived macrophages were treated with LPS (50 ng/ml) (Sigma, MO, US) and IFN-γ (100 ng/ml) (eBioscience, CA, US), in the presence or absence of activated protein C (5μg/ml) (Lilly, IN, US) for 12 hours. HO-1 expression was quantified by real time quantitative RT-PCR.

Extraction of RNA and quantitative real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the above stimulated macrophages using Trizol (Invitrogen, CA, US) and subsequently used for cDNA synthesis using Superscript III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, CA, US) per manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7500 HT Sequence Detections System (Applied Biosystems), based on our published methods [11]. The PCR primers were CGCCTTCCTGCTCAACATT-3′ and 5′-TGTGTTCCTCTGTCAGCATCAC-3′ for mouse HO-1 and 5′- AAGCGCGTCCTGGCATTGTCT-3′ and 5′-CCGCAGGGGCAGCAGTGGT-3′ for mouse acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein 36B4 (as a control). The PCR reaction was done in 25 μl solution containing 12.5 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 10 ng cDNA, and 400 nM of each primer, with the following settings: activation of the AmpliTaq Gold Polymerase at 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. The melting curve was analyzed using the ABI software and changes in gene expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (RQ Manager 1.4). Each experiment was run in duplicate. All data were normalized to 36B4 expression in the same cDNA set.

Western blot

The harvested venous thrombi were homogenized in TPER (Pierce). The extracted proteins were separated by 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel Electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred onto PVDF membranes, and then probed with primary antibodies against either β-actin (1/2000 dilution), PAI-1 (1/1000) or HO-1 (1/2000). Immuno-reactive bands were visualized with an ECL chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham) and followed by autoradiography. Densitometry analysis was assessed using NIH ImageJ and normalized to β-actin present in each sample.

Gelatin zymography

MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities were analyzed by substrate-gel electrophoresis (zymography) using SDS–PAGE (10%) containing 0.1% gelatin (Novex, Invitrogen). Briefly, equal amount of proteins were mixed with Novex Tris Glycine SDS Sample buffer (Invitrogen), loaded onto the gel, and separated by electrophoresis. The gels were washed once for 30 min at room temperature in Zymogram Renaturation Buffer (Biorad) and then incubated overnight in Zymogram Development Buffer (Biorad) at 37°C. The gels were stained with 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-2500 and destained in 5% methanol and 7% acetic acid. Gelatinolytic activity appeared as a clear band on a blue background.

ELISA

Active uPA levels within venous thrombi were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercial kit (Molecular Innovations), according to manufacturer instructions. Intra-thrombus IL-6 concentrations were determined by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Pharmingen).

Histological Analysis

The venous thrombi were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5μm thick sections. Serial sections were then subjected to H&E and Masson’s Trichrome staining. Two-color immunohistochemical staining of the paraffin sections was done using the Multiple Antigen Labeling kit from Vector Laboratories with a rabbit anti-HO-1 antibody and a rat anti-Mac-2 antibody (for macrophages), based on our published methods [13]. HO-1 and Mac-2 staining were visualized using enzyme substrate Vector NovaRED (red color) and DAB (brown/gray color), respectively. Nuclear was counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

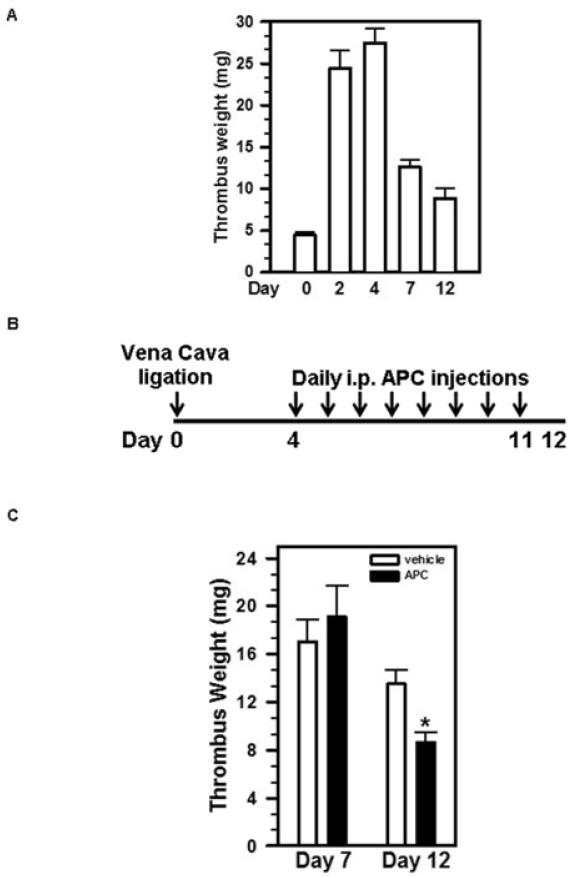

Administration of APC enhances late-stage thrombus resolution

To investigate the utility of APC in accelerating the resolution of pre-existing venous thrombus, we employed a widely used mouse model of DVT by ligating the IVC, resulting in thrombus formation within the vein [6,14-16]. Upon IVC ligation, the weight of venous thrombus formed in C57BL/6 mice increased over time, reaching its maximum (27.5±1.7 mg) on Day 4 post IVC ligation (Figure 1A). Beginning on Day 4, the thrombus weight decreased gradually, which is defined here as thrombus resolution. We chose Day 4 as the starting point of APC administration as the venous thrombus no longer expands (Figure 1A). We intraperitoneally injected APC or vehicle daily from Day 4 to Day 11 (Figure 1B). The results showed that there was no significant difference in thrombus weights between APC-treated and control animals on Day 7 post-surgery (Figure 1C), a time point that represents an early-stage thrombus resolution. On Day 12, the thrombi from APC-treated animals were significantly smaller than those of control animals (Figure 1C). Thus, APC treatment significantly accelerated late-stage thrombus resolution in mice with pre-existing thrombi.

Figure 1. Administration of APC enhances late-phase thrombus resolution.

A) Time course of thrombus resolution. Mice (n=7) were subjected to IVC ligation. The thrombus weights were measured at different time points post-surgery. B) Schematic representation of APC injection schedule. C) Mice were injected i.p. daily with APC or vehicle beginning on Day 4 after surgery. Thrombus weights were measured on Day 7 (n=7) and Day 12 (n=12-14) post-IVC ligation. Data shown are the means ± SEM. *, vehicle vs. APC, p= 0.0026.

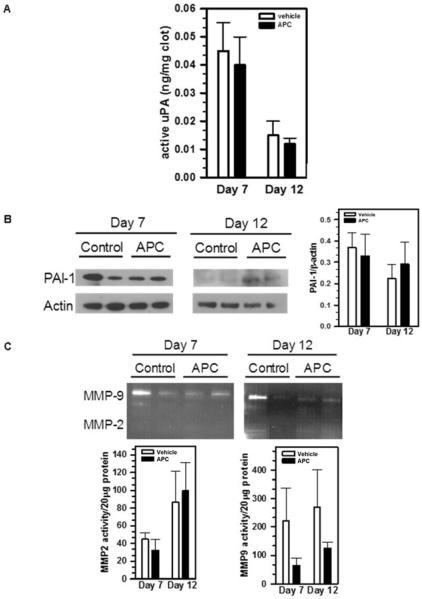

APC does not affect intra-thrombus expression of uPA, PAI-1 or MMP activities

Major proteases contributing to thrombus resolution include uPA, MMP-2 and MMP-9 [5,6]. To investigate whether APC promotes thrombus resolution by up-regulating one or more of these proteases, we harvested the venous thrombi from APC-treated and vehicle control mice on Day 7 and Day 12 post-surgery. Active uPA concentrations within the thrombi were determined by ELISA. We found that APC treatment did not alter the concentrations of active uPA on either Day 7 or Day 12 (Figure 2A). Similarly, immunoblot analyses did not detect a significant difference of intra-thrombus PAI-1 protein levels between APC-treated and control mice on either Day 7 or Day 12 (Figure 2B). In addition, gelatin zymography revealed that MMP-2 activity did not change significantly on Day 7 or Day 12, while MMP-9 activity slightly decreased in response to APC administration (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. APC does not affect intra-thrombus levels of uPA, PAI-1 or MMPs.

Thrombosed IVCs from APC-treated and control mice were harvested on Day 7 and Day 12. A) Active uPA levels were determined by ELISA, n=5; B) The amount of PAI-1 was determined by immunoblot using anti-PAI-1 antibody and quantified by NIH ImageJ; Images shown were representative of 3-5 samples. C) Active MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels were measured by gelatin zymography and quantified as above. Representative images were shown. For MMP2, p=0.28 (for Day 7) and 0.80 (for Day 12), n=3-5. For MMP9, p=0.26 (for Day 7) and 0.11 (for Day 12), n=3-5.

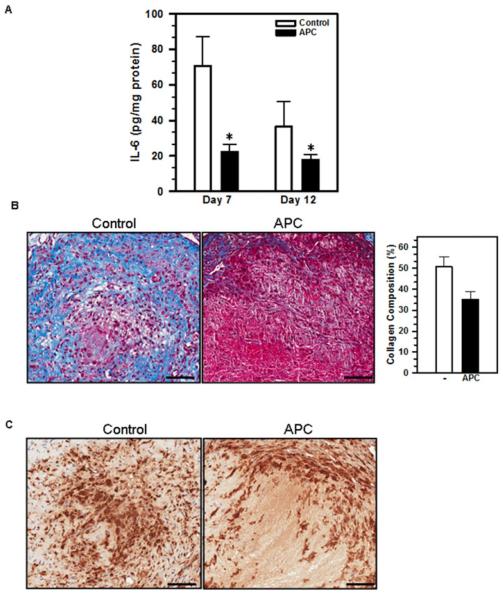

APC reduces IL-6 concentration and collagen deposition within the venous thrombi

Previously, we showed that APC inhibits macrophage production of IL-6 both in vitro and in vivo [11]. To determine if APC treatment also reduces intra-thrombus IL-6 concentrations following IVC ligation, we harvested the thrombosed IVCs on Day 7 and 12 after IVC ligation from APC-treated and control mice. The amount of IL-6 within the venous thrombi was determined by ELISA. The results showed that APC significantly reduced IL-6 levels within the venous thrombi on both Day 7 and 12 (Figure 3A), suggesting that APC administration promotes thrombus resolution by potentially suppressing intra-thrombus inflammation. In support of this hypothesis, we found that the thrombosed IVCs harvested from APC-treated mice exhibited reduced collagen deposition as compared to those from control mice, based on Masson’s Trichrome staining (Figure 3B; collagen staining in blue). Infiltrating macrophages were found in the venous thrombi of both APC-treated and control mice (Figure 3C; macrophage staining in brown).

Figure 3. APC treatment decreases IL-6 concentrations and reduces collagen deposition within venous thrombus.

Venous thrombi were taken from APC- or vehicle-treated mice on Day 7 and 12 post-surgery. A) IL-6 concentrations within the thrombus homogenates were measured by ELISA and normalized to the total amount of protein in the lysates. Data shown are the means ± SEM. *, p<0.05, vehicle vs. APC, n=5-8. B) Collagen deposition was analyzed by staining 5μm-thick paraffin sections of the venous thrombi with Masson’s Trichrome Stain. Quantification was done by NIH ImageJ of 2-4 mice per group. C) Macrophage accumulation was analyzed by immunohistochemical staining with an anti-Mac-2 antibody. Scale bars: 50 μm.

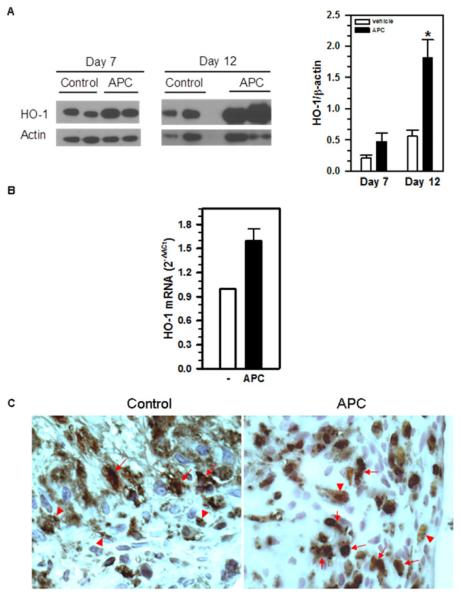

Enhancement of thrombus resolution by APC is associated with an increased HO-1 expression

Recently, HO-1, the rate-limiting enzyme in the heme degradation pathway, has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory activities [17]. In particular, it has been reported that IVC ligation leads to significant upregulation of HO-1 expression within the vessel wall and that genetic inactivation of HO-1 in mice impairs thrombus resolution [18]. To investigate whether APC administration in mice could upregulate HO-1 expression in the setting of thrombus resolution, we harvested the thrombosed IVCs from APC and vehicle-treated mice on Day 7 and 12 post-IVC ligation and determined their HO-1 protein levels by immunoblot analysis. The results showed that APC-treated mice exhibited 2.2-fold and 3.3-fold increase in HO-1 protein within the venous thrombi on Day 7 and Day 12, respectively, when compared to the vehicle-treated control mice (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. APC treatment induces HO-1 expression.

A) Mice were injected daily with vehicle or APC from Day 4 to Day 11 following IVC ligation. Intra-thrombus HO-1 levels on Day 7 and Day 12 were determined by immunoblot analysis using an anti-HO-1 antibody. The amount of HO-1 was quantified by NIH ImageJ. Data shown are the means ± SEM. *, p= 0.0181, vehicle vs. APC, n=3-5. B) Bone marrow-derived macrophages were treated with LPS and IFN-γ, with or without APC (5μg/ml) for 12 hours. HO-1 gene transcription was quantified by real-time qRT-PCR. Changes in HO-1 expression were calculated using the 2−ΔCt method (RQ Manager 1.4). The expression of 36B4 gene in the same cDNA set was used as a control. Data shown are the means ± SD of two independent experiments. C) The 5μm-thick paraffin sections of Day 12 venous thrombi from control and APC-treated mice were subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-HO-1 (in red) and anti-Mac-2 (macrophages; in brown/gray). Arrows indicate HO-1/Mac-2 double-positive cells and arrowheads indicate HO-1 or Mac-2 single-positive cells.

HO-1 is expressed by a wide range of cells, including macrophages. Given the large number of macrophages present within the venous thrombi on Day 12, we investigated whether macrophages could represent one of the potential cell types that contributed to the increased HO-1 expression in APC-treated mice. We prepared macrophages from the bone marrow based on our published methods [11] and stimulated them with LPS and IFNγ with or without APC. HO-1 gene transcription was quantified by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. The results showed that APC treatment of macrophages increased HO-1 expression by approximately 1.7 folds (Figure 4B), which is in line with the HO-1 increases observed in vivo (Figure 4A).

Immunohistochemistry showed positive HO-1 staining (in red) in the infiltrating macrophages (in brown) within the venous thrombi (Figure 4C). These results suggest that macrophages are a likely source of HO-1 within the venous thrombi in IVC-ligated mice.

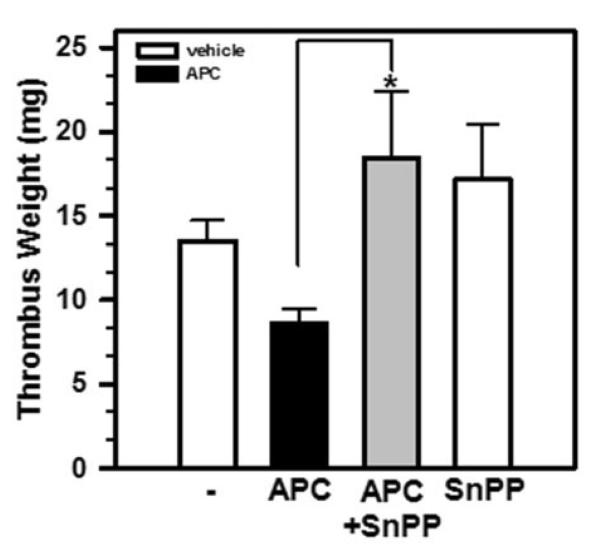

Inhibition of HO-1 activity blocks the ability of APC to enhance thrombus resolution

Correlation between the increase in HO-1 expression (Figure 4A) and the enhanced thrombus resolution (Figure 1C) in APC-treated mice suggests that the ability of APC to accelerate thrombus resolution in mice may depend on HO-1. To test this hypothesis, we administered daily Sn-protoporphyrin IX (SnPP), a well-characterized inhibitor of HO-1 [19], concurrently with APC in mice, beginning on Day 4 post-IVC ligation as described in Figure 1B. We found that the thrombus weights from mice treated with both SnPP and APC were significantly higher than those treated with APC alone (Figure 5), whereas mice treated only with SnPP had similar thrombus weights as the control mice. These results demonstrated that HO-1 activity is critical for APC enhancement of thrombus resolution.

Figure 5. APC enhances thrombus resolution via HO-1 induction.

Mice were subjected to IVC ligation and then treated daily from Day 4 and 11 post-ligation with vehicle, APC, APC plus SnPP, or SnPP alone as above. Thrombosed IVCs were retrieved on Day 12 and weighed. Data shown are the means ± SEM. *, p= 0.0013, APC vs. APC+SnPP, n=4-14.

Discussion

DVT is a significant clinical problem and no effective treatment is available. Current management for DVT, including anticoagulants and compression stockings, is inadequate due to their inability to enhance the resolution of thrombi already present in the vein. Fibrinolytic agents tPA and uPA exhibit short therapeutic windows (<2 weeks) and are inefficient at degrading mature clots that are rich in collagen. They are also associated with severe hemorrhagic complications. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop effective treatments, especially for patients with existing DVT. In this work, we report that administration of APC in mice with existing venous thrombi can significantly accelerate thrombus resolution. We also show that the ability of APC to enhance thrombus resolution is dependent on the up-regulation of intra-thrombus HO-1, a heme-degrading enzyme that possesses novel anti-inflammatory activities.

APC is a natural anticoagulant and proteolytically cleaves both activated coagulation Factor V and Factor VIII, thus shutting down the intrinsic and also extrinsic coagulation pathways. In addition to its anticoagulant function, APC possesses anti-inflammatory activities by suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-12 [20,21], increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β [22], and enhancing wound healing [23]. The underlying molecular mechanism is poorly understood. Recently, we found that the ability of APC to block IL-6 production by activated macrophages is dependent on CD11b/CD18, PAR-1 and S1P receptors [11]. These favorable properties of APC make it a potential drug candidate for treatment of DVT. Indeed, we found that administration of APC in mice, after the formation of venous thrombi, leads to significant enhancement in thrombus resolution. Surprisingly, we observed that injection of APC did not have significant effects on thrombus weights in the early stage (i.e. Day 7) of thrombus resolution. These results suggest that the anticoagulant activity of APC may not contribute significantly to its ability to enhance thrombus resolution. In support of this notion, Sood, et al. reported that inhibition of blood coagulation by heparin, either pre- or post-IVC ligation, had no effect on thrombus resolution [24]. Finally, clinical studies [25] have demonstrated an increased risk of DVT in patients with FV-Leiden, a Factor V mutant that is resistant to APC-mediated inactivation [26]. Given that the anti-inflammatory rather than anticoagulant activity of APC plays a major role in its ability to accelerate thrombus resolution, we speculate that APC should be effective as a potential treatment for DVT in FV-Leiden patients.

It is well established that the early-stage thrombus resolution is dependent on the induction of acute inflammation, which helps recruit inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages) into the nascent thrombus [14,15]. These leukocytes promote thrombus resolution by secreting uPA, MMP2 and MMP9 [6,27]. Nevertheless, inflammation is a double-edged sword and persistent inflammation also delays thrombus resolution by enhancing collagen deposition and accelerating the development of PTS [7,28]. Indeed, blockade of IL-6 activity has been shown to reduce collagen deposition and fibrosis within the vessel wall in a mouse model of thrombus resolution [7]. In this study, we find that APC promotes thrombus resolution by reducing IL-6 concentrations and collagen deposition within the venous thrombi. Interestingly, we find that APC administration did not increase the expression of known proteases that have been implicated in thrombus resolution, including uPA and MMP2. We also find that APC slightly reduced the expression of MMP9, in good agreement with a published report [29]. In addition, we find that APC treatment did not significantly decrease PAI-1 levels within the venous thrombi (Figure 2B). Another novel finding of this study is the observation that the ability of APC to enhance thrombus resolution is dependent on HO-1, the inducible isoform of heme oxygenases. Of note, we used human APC in this study. Though we find that human APC is effective in mice, it may exhibit species difference than its murine counterpart. HO-1 is expressed widely in different cell types and functions primarily to convert heme to biliverdin, iron, and carbon monoxide. Emerging evidence also implicates HO-1 in immunosuppression [17,19,30]. In particular, it has been reported that genetic inactivation of HO-1 enhances splenocyte production of TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 by 19, 22 and 37-fold [30]. Upregulation of HO-1 expression by hemin significantly delays thrombus formation upon vascular injury in mice, an effect that can be blunted by the HO-1 inhibitor SnPP [19]. Finally, HO-1 deficiency significantly impairs thrombus resolution following the ligation of IVCs [17]. These published studies provide further support for our proposed mechanism that APC enhances thrombus resolution and reduces post-thrombotic syndrome by inducing HO-1 expression, potentially in infiltrating macrophages.

In summary, we showed in this study that administration of APC in mice with existing DVT significantly accelerates thrombus resolution via a HO-1-dependent mechanism. The ability of APC to enhance thrombus resolution and suppress fibrosis makes it an attractive drug candidate for the treatment of DVT in human patients. Importantly, as APC-mediated enhancement of thrombus resolution primarily depends on its anti-inflammatory activity, unique APC variants that exhibit low anticoagulant activity but possess intact anti-inflammatory function, such as 5A-APC [31], could be potential drug candidates that can promote thrombus resolution without the risks of severe bleeding, thus offering better clinical care for patients with DVT.

Acknowledgement

We thank Elizabeth Smith for help with histology. This work was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (HL-054710 HL054710 and AI078365 to L. Zhang and HL083917 to R. Sarkar).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

We have no conflict of interests to declare.

Reference List

- 1.Ashrani AA, Heit JA. Incidence and cost burden of post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;28:465–76. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn SR. The post thrombotic syndrome. Thromb Res. 2011;127(Suppl 3):S89–S92. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(11)70024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khanna AK, Singh S. Postthrombotic syndrome: surgical possibilities. Thrombosis. 2012;2012:520604. doi: 10.1155/2012/520604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, Buller HR, Decousus H, Gallus AS, Lensing AW, Misselwitz F, Prins MH, Raskob GE, Segers A, Verhamme P, Wells P, Agnelli G, Bounameaux H, Cohen A, Davidson BL, Piovella F, Schellong S. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499–510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakefield TW, Myers DD, Henke PK. Mechanisms of venous thrombosis and resolution. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:387–91. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahi S, Lee JG, Lovett DH, Sarkar R. Differential transcriptional activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase by experimental deep venous thrombosis and thrombin. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:539–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wojcik BM, Wrobleski SK, Hawley AE, Wakefield TW, Myers DD, Jr., Diaz JA. Interleukin-6: a potential target for post-thrombotic syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esmon CT. The interactions between inflammation and coagulation. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:417–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakata Y, Curriden S, Lawrence D, Griffin JH, Loskutoff DJ. Activated protein C stimulates the fibrinolytic activity of cultured endothelial cells and decreases antiactivator activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:1121–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riewald M, Petrovan RJ, Donner A, Mueller BM, Ruf W. Activation of endothelial cell protease activated receptor 1 by the protein C pathway. Science. 2002;296:1880–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1071699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao C, Gao Y, Li Y, Antalis TM, Castellino FJ, Zhang L. The efficacy of activated protein C in murine endotoxemia is dependent on integrin CD11b. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1971–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI40380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosnier LO, Zlokovic BV, Griffin JH. The cytoprotective protein C pathway. Blood. 2007;109:3161–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bi Y, Gao Y, Ehirchiou D, Cao C, Kikuiri T, Le A, Shi S, Zhang L. Bisphosphonates cause osteonecrosis of the jaw-like disease in mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:280–90. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphries J, McGuinness CL, Smith A, Waltham M, Poston R, Burnand KG. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) accelerates the organization and resolution of venous thrombi. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:894–9. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuinness CL, Humphries J, Waltham M, Burnand KG, Collins M, Smith A. Recruitment of labelled monocytes by experimental venous thrombi. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:1018–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh I, Burnand KG, Collins M, Luttun A, Collen D, Boelhouwer B, Smith A. Failure of thrombus to resolve in urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene-knockout mice: rescue by normal bone marrow-derived cells. Circulation. 2003;107:869–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050149.22928.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paine A, Eiz-Vesper B, Blasczyk R, Immenschuh S. Signaling to heme oxygenase-1 and its anti-inflammatory therapeutic potential. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tracz MJ, Juncos JP, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Ackerman AW, Katusic ZS, Nath KA. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 is a beneficial response in a murine model of venous thrombosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1882–90. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindenblatt N, Bordel R, Schareck W, Menger MD, Vollmar B. Vascular heme oxygenase-1 induction suppresses microvascular thrombus formation in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:601–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118279.74056.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grey ST, Tsuchida A, Hau H, Orthner CL, Salem HH, Hancock WW. Selective inhibitory effects of the anticoagulant activated protein C on the responses of human mononuclear phagocytes to LPS, IFN-gamma, or phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1994;153:3664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephenson DA, Toltl LJ, Beaudin S, Liaw PC. Modulation of monocyte function by activated protein C, a natural anticoagulant. J Immunol. 2006;177:2115–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toltl LJ, Beaudin S, Liaw PC. Activated protein C up-regulates IL-10 and inhibits tissue factor in blood monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:2165–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson CJ, Xue M, Thompson P, Davey RA, Whitmont K, Smith S, Buisson-Legendre N, Sztynda T, Furphy LJ, Cooper A, Sambrook P, March L. Activated protein C prevents inflammation yet stimulates angiogenesis to promote cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:284–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.00130311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sood V, Luke C, Miller E, Mitsuya M, Upchurch GR, Jr., Wakefield TW, Myers DD, Henke PK. Vein wall remodeling after deep vein thrombosis: differential effects of low molecular weight heparin and doxycycline. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson FA, Jr., Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107:I9–16. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078469.07362.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahlback B, Carlsson M, Svensson PJ. Familial thrombophilia due to a previously unrecognized mechanism characterized by poor anticoagulant response to activated protein C: prediction of a cofactor to activated protein C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1004–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deatrick KB, Eliason JL, Lynch EM, Moore AJ, Dewyer NA, Varma MR, Pearce CG, Upchurch GR, Wakefield TW, Henke PK. Vein wall remodeling after deep vein thrombosis involves matrix metalloproteinases and late fibrosis in a mouse model. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:140–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roumen-Klappe EM, Janssen MC, Van Rossum J, Holewijn S, Van Bokhoven MM, Kaasjager K, Wollersheim H, Den Heijer M. Inflammation in deep vein thrombosis and the development of post-thrombotic syndrome: a prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:582–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng T, Petraglia AL, Li Z, Thiyagarajan M, Zhong Z, Wu Z, Liu D, Maggirwar SB, Deane R, Fernandez JA, LaRue B, Griffin JH, Chopp M, Zlokovic BV. Activated protein C inhibits tissue plasminogen activator-induced brain hemorrhage. Nat Med. 2006;12:1278–85. doi: 10.1038/nm1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapturczak MH, Wasserfall C, Brusko T, Campbell-Thompson M, Ellis TM, Atkinson MA, Agarwal A. Heme oxygenase-1 modulates early inflammatory responses: evidence from the heme oxygenase-1-deficient mouse. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1045–53. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerschen EJ, Fernandez JA, Cooley BC, Yang XV, Sood R, Mosnier LO, Castellino FJ, Mackman N, Griffin JH, Weiler H. Endotoxemia and sepsis mortality reduction by non-anticoagulant activated protein C. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2439–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]