Abstract

BACKGROUND

Successful bowel preparation is important for safe, efficacious, cost-effective colonoscopy procedures, however poor preparation is common.

OBJECTIVE

We sought to determine if there was an association between health literacy and comprehension of typical written instructions on how to prepare for a colonoscopy to enable more targeted interventions in this area.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional observational study

SETTING

Primary care clinics and federally qualified health centres in Chicago, Illinois.

PATIENTS

764 participants (mean age: 63 years; Standard Deviation: 5.42) were recruited. The sample was from a mixed socio-demographic background and 71.9% of the participants were classified as having adequate health literacy scores.

INTERVENTION

764 participants were presented with an information leaflet outlining the bowel preparatory instructions for colonoscopy.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Five questions assessing comprehension of the instructions in an ‘open book’ test.

RESULTS

Comprehension scores on the bowel preparation items were low. The mean number of items correctly answered was 3.2 (Standard Deviation, 1.2) out of a possible 5. Comprehensions scores overall and for each individual item differed significantly by health literacy level (all p<0.001). After controlling for gender, age, race, socio-economic status and previous colonoscopy experience in a multivariable model, health literacy was a significant predictor of comprehension (inadequate vs. adequate: β = −0.2; p < 0.001; marginal vs. adequate: β = −0.2; p < 0.001).

LIMITATIONS

The outcome represents a simulated task and not actual comprehension of preparation instructions for participants’ own recommended behavior.

CONCLUSIONS

Comprehension of a written colonoscopy preparation leaflet was generally low and significantly more so among people with low health literacy. Poor comprehension has implications for the safety and economic impact of gastroenterological procedures such as colonoscopy. Therefore future interventions should aim to improve comprehension of complex medical information by reducing literacy-related barriers.

Keywords: Health literacy, Colonoscopy, Comprehension, Socio-economic status, Preparation

INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy is considered the ‘gold-standard’ test in order to detect and screen for colorectal cancer1,2,3 with millions of procedures performed each year.4 The effectiveness of colonoscopy is dependent, to a large degree, on successful bowel purgation. Inadequate bowel preparation can reduce test adenoma detection rate5–8 and increase the likelihood of adverse events such as perforation and peritoneal contamination.9 Colonoscopies performed on patients with inadequate bowel preparation take longer to perform,10 are more likely to result in an incomplete procedure and result in higher rates of repeat procedures.7 The economic implications of poor bowel preparation are considerable.11

Responsibility for preparing the colon prior to colonoscopy falls largely on the patient and generally involves the consumption of a prescribed purgative and adherence to a strict diet for 1–2 days. Preparing for colonoscopy can be an arduous task for patients and while multiple clinical trials show high rates of efficacy for a range of bowel purgatives,12 the issue of inadequate preparation in actual practice remains a significant and common problem.5,13–17

Evidence suggests that the root causes of inadequate preparation is unlikely to be motivational18 and may instead be a result of misunderstanding the often complex requirements.15 These individual capabilities are generally encompassed by the term ‘health literacy’, defined here as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”.19 National estimates suggest adequate levels of health literacy are lacking in approximately one in three American adults, with lower socio-economic status groups being overrepresented.20

This paper will report on the comprehension of a hypothetical bowel preparation instruction leaflet in a large cross-sectional cohort of older patients herein referred to as the ‘LitCog’ study. We hypothesized that health literacy would be associated with comprehension, even after controlling for socio-economic variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedure

Participants aged 55–74 were recruited from primary care clinics and federally qualified health centres in Chicago, Illinois starting August 2008 through October 2010. A sample of 1768 eligible patients were reached by research staff and invited to participate in the study. Initial screening deemed 192 subjects as ineligible due to severe cognitive or hearing impairment, limited English proficiency, or not being connected to a clinic physician (defined as < 2 visits in two years). In addition, 738 refused, 14 were deceased, and 20 were eligible but had scheduling conflicts. The final sample included 804 participants, for a determined cooperation rate of 51 percent following American Association for Public Opinion Research guidelines. Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing data on the comprehension measure or socio-demographic variable items (n = 40), giving a final sample of 764. Data for income was frequently missing (n = 41; > 5%) and, therefore, coded as a separate category and included in the analysis. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures and all participants gave informed consent.

Consenting participants were invited to attend an interview involving the completion of a battery of measures including health literacy, comprehension of a colonoscopy preparation task and socio-demographic variables.

Measures

Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA;21)

The TOFHLA is composed of two-subscales (numeracy and literacy). The numeracy subscale involves the participant answering 17 questions based on presented examples of healthcare information (e.g., clinic appointment details). The reading subscale uses the Cloze procedure22 where participants are presented with three passages, increasing in reading difficulty, describing health relevant information. Each passage has between 14 and 20 gaps and for each, participants must choose the appropriate word to complete the sentence from a list of 4 possibilities. The scores of the two subscales are combined and weighted to provide a composite score of health literacy ranging from 0–100 and categorized into pre-determined groups of inadequate (0–59), marginal (60–74), and adequate (75–100) literacy. These groups were defined by the original authors of the TOFHLA following convergent validation with measures of general literacy.21

Bowel Preparation Comprehension

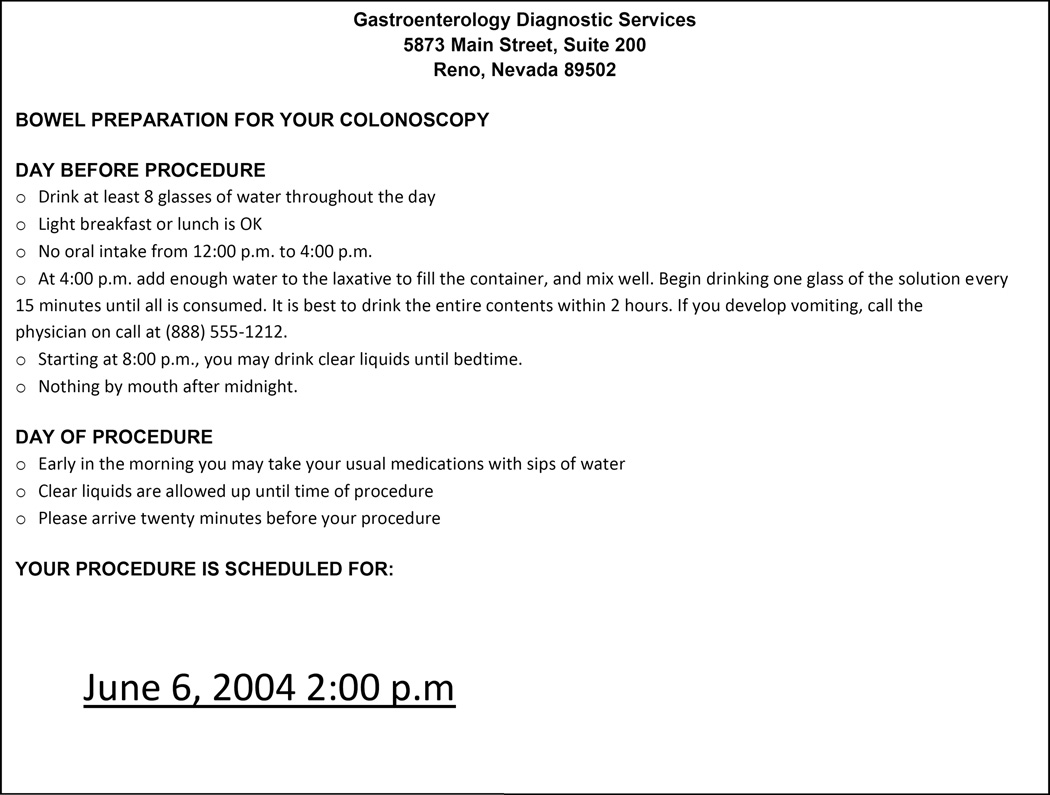

The comprehension measure was developed specifically for this study. Participants were presented with written instructions on how to prepare for a colonoscopy (Figure 1). The instructions consisted of 171 words and required a 9th grade reading level according to the Flesch-Kincaid readability test. A total of 5 open-ended questions were asked verbally in a structured interview and responses noted as either correct or incorrect according to pre-defined answers specified by the researchers. Subjects could ask clarifying questions but interviewers did not assist them in understanding the material nor did they provide any further interpretation. These items were derived from the content, as the information required to correctly answer each question was contained within the instructions. Participants could refer to the instruction leaflet throughout the task.

Figure 1.

Preparatory instructions for participants

Socio-demographic items

Participants completed a questionnaire asking about gender, age (55–59, 60–64, 65+), race (African American, White, Other), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate or higher), income (refused, less than $24,999, $25-49,999, $50,000+) and previous experience of a colonoscopy.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 18.0. Descriptive statistics were computed for the TOFHLA and comprehension measure. Differences in individual comprehension items as well as total comprehension scores (0–5) by health literacy category were examined using Chi-Square and one-way ANOVA tests, respectively. Multivariable linear regression was used to observe the impact of socio-economic status and health literacy on comprehension of the bowel preparation instructions.

RESULTS

The sample characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 63 years (SD = 5.4). The majority of participants were female (68.1%), Non-Hispanic White (49.9%) or African American (39.5%). The socioeconomic background of participants was mixed, with over half of all participants (51.8%) possessing at least a college graduate degree and similar proportions reported earning more than $50,000 per year (51.6%). The majority of participants had previously had a colonoscopy (81.9%). Adequate health literacy scores were recorded for 71.9% of participants.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 244 | 31.9 |

| Female | 520 | 68.1 |

| Age | ||

| 55–59 | 241 | 31.5 |

| 60–64 | 241 | 31.5 |

| 65+ | 282 | 36.9 |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 91 | 11.9 |

| High school graduate | 111 | 14.5 |

| Some college | 166 | 21.7 |

| ≥ College graduate | 396 | 51.8 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 302 | 39.5 |

| White | 381 | 49.9 |

| Other | 81 | 10.6 |

| Income | ||

| Refuse | 41 | 5.4 |

| <$24,900 | 219 | 28.7 |

| $25,000–$49,900 | 110 | 14.4 |

| $50,000 or more | 394 | 51.6 |

| Previous colonoscopy | ||

| No | 138 | 18.1 |

| Yes | 626 | 81.9 |

| Health literacy | ||

| Inadequate (0–59) | 89 | 11.6 |

| Marginal (60–74) | 126 | 16.5 |

| Adequate (75–100) | 549 | 71.9 |

Overall, the mean number of items correctly answered was 3.2 (SD, 1.2) out of a possible 5 (Table 2). Total comprehension scores differed significantly by health literacy group (p<0.001), increasing at each subsequent threshold of health literacy (mean scores ranged from 1.9 (SD = 0.8) to 2.5 (SD = 0.9) and 3.6 (SD = 1.0) for inadequate, marginal and adequate groups respectively). For each individual item, significant differences in the percentage of correct responses were observed across health literacy groups (all p<0.001), with correct responses reducing at each level of health literacy (Table 2). Fewer than 50% of the sample correctly responded to items pertaining to the time to stop eating solid food on the day before the appointment and the volume of water that can be consumed on the day of the procedure; the latter only being correctly answered by 2.2% of those with inadequate health literacy.

TABLE 2.

Comprehension of bowel preparation items by health literacy score (% correct)

| Questions | All n = 764 |

Inadequate n = 89 |

Marginal n = 126 |

Adequate n =549 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many glasses of water should you drink on the day before your procedure? |

97.6 | 85.4 | 99.2 | 99.5 | <0.001 |

| On the day before your colonoscopy, by what time do you need to stop eating solid food? |

46.2 | 34.8 | 31.0 | 51.2 | <0.001 |

| How much milk can you drink on the morning of your colonoscopy? |

85.9 | 65.2 | 78.6 | 91.6 | <0.001 |

| What time does the card say you should arrive for your procedure? |

53.7 | 6.8 | 25.6 | 68.3 | <0.001 |

| How much water can you drink on the day of the procedure? |

36.0 | 2.2 | 15.1 | 47.0 | <0.001 |

| Total Correct, Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.2) | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.0) | <0.001 |

In the multivariable model (Table 3), health literacy was the strongest predictor of comprehension (inadequate vs. adequate: β = −0.2; p < 0.001; marginal vs. adequate: β = −0.2; p < 0.001). Compared with participants who had obtained a college degree, those with lower levels of education performed significantly worse on the task (some college: β = −0.1; p = 0.04; high school graduate: β = −0.1; p = 0.02; less than high school: β = −0.1, p = 0.01). African Americans (β = −0.2, p < 0.001) and participants from other ethnic minorities (β = −0.1, p < 0.001) had significantly lower comprehension scores. Finally, individuals refusing to report their income (β = −0.1; p = 0.001) and those earning under $24,999 (β = −0.2; p <0.001) demonstrated significantly worse comprehension than those in the highest income category. It was noteworthy that age, gender and previous colonoscopy use were not associated with comprehension scores (all p > 0.05). The multivariable model explained 37% of the variance in comprehension scores.

TABLE 3.

Multivariable linear regression model predicting comprehension

| β (95% CI) | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.0 | 0.41 |

| Age group | |||

| 55–59 (ref) | - | - | - |

| 60–64 | 0.2 (0, 0.3) | 0.1 | 0.69 |

| 65+ | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.1) | 0.0 | 0.72 |

| Education | |||

| < High school | −0.4 (−0.7, −0.1) | −0.1 | 0.01 |

| High school graduate | −0.3 (−0.5, 0.0) | −0.1 | 0.02 |

| Some COLLEGE | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | −0.1 | 0.04 |

| ≥ College graduate (ref) | - | - | - |

| Race | |||

| African American | −0.4 (−0.6, −0.3) | −0.2 | <0.001 |

| Other | −0.5 (−0.8, −0.3) | −0.1 | <0.001 |

| White (ref) | - | - | - |

| Income | |||

| Refuse | −0.6 (−0.9, −0.2) | −0.1 | 0.001 |

| <$24,900 | −0.4 (−0.6, −0.2) | −0.2 | <0.001 |

| $25,000–$49,900 | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | −0.1 | 0.04 |

| $50,000+ (ref) | - | - | - |

| Previous colonoscopy | |||

| Yes | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| No (ref) | - | - | - |

| Health literacy | |||

| Inadequate | −0.9 (−1.1, −0.6) | −0.2 | <0.001 |

| Marginal | −0.5 (−0.7, −0.3) | −0.2 | <0.001 |

| Adequate (ref) | - | - | - |

F(14, 749) = 33.04, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.37.

DISCUSSION

In this sample of older American individuals, comprehension of a representative written bowel preparation instruction leaflet was low, particularly for those with limited health literacy. On average these groups were able to understand between two and three of the 5 seemingly simple instructions on the leaflet, despite being able to refer back to the material while answering questions. In a multivariable model controlling for a number of socio-economic factors, inadequate health literacy was the strongest predictor of poor comprehension. Socio-economic factors including education, income and race were also associated with comprehension. Previous experience of colonoscopy was not associated with comprehension, suggesting that assumptions of comprehension should not be made for specific patient groups that frequently undergo preparation.

While previous studies have demonstrated specific socio-demographic variables (e.g., gender and education), that are associated with poor preparation14,16 this if the first time a health literacy assessment has been used to demonstrate its association with comprehension of a bowel preparation regimen. First, our findings demonstrate that poor health literacy is a risk factor of at least equal importance to these other well-known covariates. Second, the observed relationship suggests clinicians and policy makers should be encouraged to make use of the techniques employed by the rapidly emerging health literacy field in order to design patient-centered information materials.

The traditional approach to improving comprehension of patient information has been to simplify and shorten words in order to improve the ‘readability’ of the text.23–25 However, readability statistics have been shown to be unreliable.26 Additionally, merely altering text readability has had limited success at ameliorating differences in performance across patients with limited versus adequate literacy.27,28 A more comprehensive approach to improving health information may be needed. For example there are now well-known associations between health literacy and the broader spectrum of cognitive abilities.29–31 As noted by Wolf and colleagues,32 these recent developments should encourage health literacy experts to engage with researchers from fields such as adult education, cognitive epidemiology and psychology in order to design optimal health information interventions. Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that supplementing print-based information with intensive interventions, such as multimedia video tutorials or health education classes, can improve health-related outcomes and their antecedents.33 However, consideration would have to be given to the cost-effectiveness of such interventions.

Current recommendations for improving the quality of patient information include, ensuring adequate font size, ordering information so that it is intuitive to the user, using passive language, providing headings to aid navigation, chunking information into more manageable sizes, repetition, use of imagery and making space for frequently asked question sections.34, 35 Expressions that are commonly used by clinicians (e.g., clear liquids) have also been shown to be problematic36 and should have their meaning clarified, using language confirmed by patients prior to their use and altered accordingly.37 It has been shown that by providing patients with concrete examples (e.g., apple juice, water, tea) and an easy to follow test for distinguishing between a ‘clear’ and ‘unclear’ liquid,35 comprehension and clinical outcomes can be improved. Several research papers and guides exist that provide techniques for patient information design.37

In this study, some items were more difficult to answer than others, with items including time calculation being answered particularly poorly. For example, reporting the correct time to arrive for the appointment required participants to subtract twenty minutes from the stated procedure time of 2:00pm, a task which was completed correctly by only 6.8% of the inadequate health literacy group, compared with 68% of the adequate literacy group. This finding is particularly troublesome when considering how frequently statements such as these are used prior to gastroenterology appointments. Medical instructions should be made as explicit as possible, which in turn will likely benefit all patients of varying levels of literacy. Additionally, even when instructions are stated explicitly, care should be taken to insure that patients, especially those with limited literacy, demonstrate adequate understanding of the information. Techniques such as the ‘teach back’ method are particularly effective for this purpose.38

Together with evidence from the field of health literacy, our research from this one sample of instructions suggests that poor bowel preparation could potentially occur due to poor comprehension of the task set.35 This is supported by additional studies that have demonstrated the failure of interventions to improve bowel preparation quality by persuading patients of the benefits of preparation adherence.18

A strength of this study is the large socio-demographically diverse sample with a range of literacy levels. The findings are, therefore, likely to translate to a wider US population. In addition to improving preparatory instructions for colonoscopy, our findings will assist research teams, clinicians and policy makers that are involved with designing patient information materials for similar procedures, such as Barium Enema, CT Colonograhy or MR Colonography.

This research has limitations. Specifically, while participants were all eligible for screening by colonoscopy, and their prior experience accounted for, our outcome represents a simulated task and not actual comprehension of preparation instructions for participants’ own recommended behavior. As a result, we were unable to link our data to more clinically relevant objective outcomes. As a simulated task, patients might have also applied greater mental effort if this directly applied to an actual, upcoming colonoscopy rather than a hypothetical scenario and therefore participant anxiety levels are unlikely to be equal to patients preparing to undergo a stressful medical procedure. We may reasonably expect individuals that are experiencing this situation to make more mistakes due to this temporary change to their stress levels caused by undergoing such a procedure.39 In addition, the instructions may have been less detailed and less cohesive than those used in current clinical practice, resulting in an overestimation of the lack of comprehension within clinical populations. However, patients were given unlimited time and the assessment was open book, which still appear to suggest that the instructions were difficult. As a final limitation to mention, only one specific example of colonoscopy preparation instructions were tested, which might not represent how all clinical practices educate their patients to the task. A final limitation is the high levels of experience with colonoscopy that were observed. Although this was controlled for, familiarity with the procedure and similar information materials may have improved comprehension thereby underestimating the problem among a general patient sample with less experience.

Future research should collect (in addition to the measures recorded here) clinical outcome data such as objective bowel preparation quality, time to cecum, withdrawal time and need for further investigation. Interventions could then be conducted, similar to those reported by Spiegel and colleagues,35 using preparation instructions encompassing the health literacy principles discussed previously.

In conclusion, bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy is a patient-led activity, which can have major implications for the safety, efficacy, and cost of the procedure. Our findings indicate that comprehension of a written instruction leaflet was poor. Furthermore, individual differences in health literacy were strongly predictive of comprehension over and above socio-economic factors and colonoscopy experience. These findings have implications for the design of patient information materials for bowel preparation regimens, and also highlight that more attention should be given to patients that are limited in health literacy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG030611; PI: Wolf)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: None declared

Presentation: The study will be presented as a poster at the Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Conference (New Orleans, Louisiana; 11th–14th April, 2012).

Contributions of authors:

SS: Substantial contributions to: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

CvW: Substantial contributions to: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

LM: Substantial contributions to: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

LC: Substantial contributions to: conception and design; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

EW: Substantial contributions to: conception and design; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

MS: Substantial contributions to: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

MW: Substantial contributions to: conception and design; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published

REFERENCES

- 1.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–750. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Targeted, Updated Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeff LC, Richards TB, Shapiro JA, et al. How many endoscopies are performed for colorectal cancer screening? Results from CDC’s survey of endoscopic capacity. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1670–1677. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76–79. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leaper M, Johnston MJ, Barclay M, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Reasons for failure to diagnose colorectal carcinoma at colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2004;36:499–503. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne MF. The curse of poor bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1587–1590. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein C, Thorn M, Monsees K, Spell R, O’Connor JB. A prospective study of factors that determine cecal intubation time at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:72–75. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:792–809. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0536-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, et al. A patient education program is cost-effective for preventing failure of endoscopic procedures in a gastroenterology department. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1786–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen DL, Wieland M. Risk factors predictive of poor quality preparation during average risk colonoscopy screening: the importance of health literacy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:369–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan WK, Saravanan A, Manikam J, Goh K, Mahadeva S. Appointment waiting times and education level influence the quality of bowel preparation in adult patients undergoing colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day LW, Walter LC, Velayos F. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in the elderly patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1197–1206. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calderwood AH, Lai EJ, Fix OK, Jacobsen BC. An endoscopist-blinded, randomized, controlled trial of a simple visual aid to improve bowel preparation for screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, editors. National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C, White S. Literacy in everyday life: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor WL. Cloze procedure: A new tool for measuring readability. Journalism Quart. 1953;30:415–433. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:221–233. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin GH. Smog grading - a new readability formula. J Reading. 1969;12:639–646. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laubach R, Koschnick K. Using readability formulas for easy adult materials. Syracuse, NY: New Readers Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knapp P, Raynor DK, Silcock J, Parkinson B. Performance-based readability testing of participant information for a Phase 3 IVF trial. Trials. 2009;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerber BS, Brodsky IG, Lawless KA, et al. Implementation and Evaluation of a Low-Literacy Diabetes Education Computer Multimedia Application. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1574–1580. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Arnold C, Murphy PW, Herbst M, Bocchini JA. A polio immunization pamphlet with increased appeal and simplified language does not improve comprehension to an acceptable level. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson BA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:723–726. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0566-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson EA, Wolf MS, Curtis LM, et al . Literacy, cognitive ability, and the retention of health-related information about colorectal cancer screening. J Health Commun. 2010;15:s116–s125. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray C, Johnson W, Wolf MS, Deary IJ. The association between cognitive ability across the lifespan and health literacy in old age: The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Intelligence. 2011;39:178–187. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf MS, Wilson EAH, Rapp DN, et al. Literacy and learning in health care. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S275–S281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, Berkman ND, Donahue KE, Crotty K. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: A systematic review. J Health Commun. 2011;16:s30–s54. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson EAH, Wolf MS. Working memory and the design of health materials: a cognitive factors perspective. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel BMR, Talley J, Shekelle P, et al. Development and validation of a novel patient educational booklet to enhance colonoscopy preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:875–883. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy I, Jhaveri M, Shankar U, Selby L. Poor comprehension of colon preparation process in an Appalachian population. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:143–146. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raynor DK, Knapp P, Silcock J, Parkinson B, Feeney K. ”User-testing” as a method for testing the fitness-for-purpose of written medicine information. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Wagner C, Knight K, Halligan S, et al. Patient experiences of colonoscopy, barium enema and CT colonography: a qualitative study. Brit J Radiol. 2009;82:13–19. doi: 10.1259/bjr/61732956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]