Abstract

Efficacy equivalent to that reported in other common adult solid tumors considered to be chemotherapy-sensitive has been reported with Docetaxel in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer. However, in contrast to other cancers, the expected increase in efficacy with the use of chemotherapy in earlier disease states has not been reported to date in prostate cancer. On the basis of these observations, we speculated that the therapy development paradigm used successfully in other cancers may not apply to the majority of prostate cancers. Several lines of supporting clinical and experimental observations implicate the tumor microenvironment in prostate carcinogenesis and resistance to therapy.

We conclude that a foundation to guide the development of therapy for prostate cancer is required. The therapy paradigm we propose accounts for the central role of the tumor microenvironment in bone and, if correct, will lead to microenvironment-targeted therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Recent clinical observations compel a reassessment of the framework used to develop therapy for patients with prostate cancer. The therapeutic paradigm used in the development of chemotherapy for solid tumors has been to first optimize new therapies in the advanced disease setting, followed by the gradual integration of those therapies into treatment for disease at earlier stages, with the expectation of increased survival. However, recently reported results of clinical trials suggest that this approach, despite its proven success in other common adult solid tumors, does not apply to prostate cancer. This unexpected finding prompts the search for a better understanding of the underlying biology of prostate cancer.

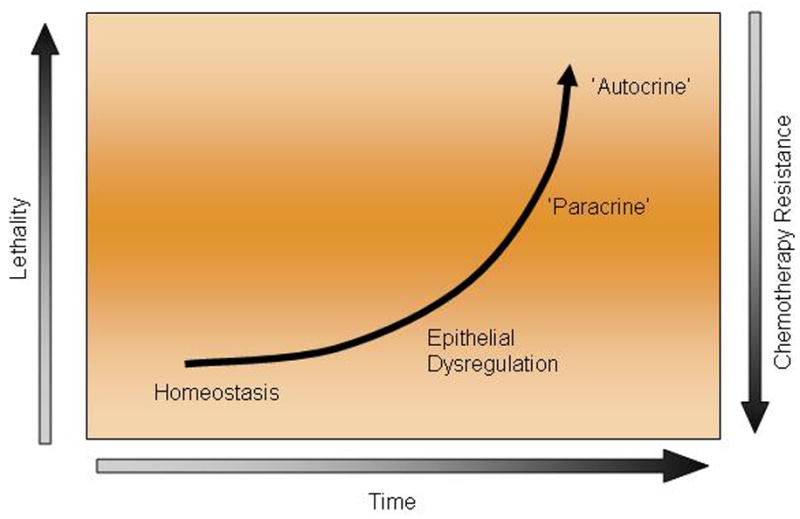

In this Perspectives, we present a conceptual biological framework that proposes the tumor microenvironment as the key aspect of prostate cancer evolution. The properties of the microenvironment are likely to account for the stage-dependent chemotherapy-response profile of the disease. Experimental observations and clinical-pathologic associations suggest that prostate cancer progresses through a microenvironment-dependent state (which for the purpose of this discussion will be called paracrine state) and on to a microenvironment-independent state (epitheliocentric; and here called autocrine state) during its clinical evolution. The progression of prostate cancer to this autocrine state may explain why more advanced prostate cancer is chemotherapy-responsive. This may account for a relationship between prostate cancer progression and chemotherapy responsiveness (therapy-response profile) and distinguish prostate cancer from other cancers. (Fig 1)

Fig 1.

Proposed association between time to prostate cancer, lethality, and resistance to chemotherapy.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE IMPORTANCE OF THE MICROENVIRONMENT IN THE BIOLOGY AND PROGRESSION OF PROSTATE CANCER

Chemotherapy Response by Disease State

The development of chemotherapy for prostate cancer was initially hampered by the perception that elderly patients would have limited tolerance to chemotherapy. Moreover, in the era before prostate-specific antigen concentration was used to detect prostate cancer, the absence of measurable disease or some other acceptable surrogate to measure treatment outcome resulted in great skepticism about the merits of chemotherapy.1 However, chemotherapy became an accepted part of the treatment strategy for advanced prostate cancer when prospectively conducted and properly controlled studies demonstrated palliation2 and, later, modest prolongation of survival with chemotherapy.2,3

These promising results prompted efforts to integrate chemotherapy into the treatment of prostate cancer at earlier stages of disease progression. These efforts were based on a theoretical framework similar to that used for treating other solid tumors. First, various combinations of agents were developed and studied.4-6 Chemotherapy was then used in combination with androgen ablation for earlier-stage disease (i.e., castration-naïve disease)7,8 or in combination with molecularly targeted therapies.9,10 Last, trials of neoadjuvant therapy were conducted.11-17 Despite the strong rationale for this approach, the reported results to date have been disappointing. Reported studies have not demonstrated improved outcomes with initial androgen ablation and chemotherapy for most men with prostate cancer. Studies combining chemotherapy with androgen ablation for the initial treatment of patients with metastatic prostate cancer have, thus far, revealed no survival benefit in unselected patients.7,8 Adjuvant treatment with docetaxel is still being studied (Table 1A), and only two relatively small adjuvant chemotherapy studies have been reported to date.18.19 Preoperative studies integrating chemotherapy, alone or in combination with androgen ablation, failed to achieve a degree of cytoreduction analogous to that observed in other common solid tumors. 11-17 Phase II neoadjuvant studies have, in fact, been characterized by a striking absence of meaningful pathologic regression of primary cancers. Two phase III studies are under way (Table 1B).

Table 1.

Docetaxel-based trials

| A. Adjuvant phase III trials | Randomization | Primary endpoint | Planned accrual status |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPCG-12 NCT00376792 | Docetaxel ×6 vs observation | bPFS | 396 |

| SWOG 9921 NCT00004124 | Mitoxantrone × 6 cycles+prednisone+ADT× 2yrs vs ADT× 2yrs | bPFS | Closed early |

| TAX3501 (Sanofi -Aventis) NCT00283062 | Docetaxel+prednisone × 6cs +ADT vs ADT alone | bPFS | Closed early |

| VA CSP NCT00132301 | Docetaxel +Prednisone× 6cs vs observation | bPFS | 636 |

| B. Neoadjuvant phase III trials | |||

| CALGB 90203-NCT00430183 | Docetaxel×6+ADT×18/24wks vs RP alone | bPFS | 700 |

| GETUG 12 – NCT00055731 | Docetaxel +Estramustine prior to RP or RT and ADT ×3yrs vs local and ADT ×3yrs | bPFS | 250 |

The data reported thus far, although not conclusive, predict that earlier use of chemotherapy in prostate cancer will not result in improved efficacy similar to that observed with other cancers. A modest increase in efficacy may yet be observed, but the likelihood that such efforts will have a major effect on survival is small.

These unexpected findings have profoundly affected our view of prostate cancer. The view emerging from these clinical observations serves as the impetus for further investigation. The goal of future studies will be to confirm and understand the paradoxical clinical observation that earlier-stage prostate cancer may be more resistant to chemotherapy than are advanced castrate-resistant cancers. Given that chemotherapy predominantly affects tumor cells, the insensitivity of earlier-stage prostate cancer to chemotherapy supports that tackling tumor cells per se is not sufficient to inhibit prostate cancer progression.

Organ-Specific Disease Spread and Targeting

The clinical presentation of patients with advanced prostate cancer is characterized by a high frequency of bone-homing and bone-forming metastases. Furthermore, complications due to bone metastases (pain, fractures, paralysis due to spinal cord compression, and cranial nerve root involvement) are frequent sources of suffering for these patients. Thus, clinicians have been focused on developing specific strategies to therapeutically target bone metastases.

A long-standing empiric treatment approach adopted by oncologists is to target sites of preferred metastasis for cancers with a predictable pattern of spread, such as pulmonary resection for selected patients with sarcomas and hepatic perfusion or resection for patients with colon cancer. This strategy has been extended to prostate cancer with the use of bone-homing radiopharmaceutical agents. We and others have exploited the properties of these radiopharmaceuticals for palliating symptoms and treating patients in the hope of prolonging their survival. Indeed, initial studies with strontium-89 revealed symptom relief and perhaps delayed disease progression to new metastatic sites.20,21 Since then, similar effects have been observed by others using various radiopharmaceutical agents both alone and in combination with chemotherapy.22,23 Randomized studies are currently under way to prospectively confirm these findings.

These clinical observations indirectly support the concept that targeting organ-specific microenvironment implicated in disease progression may alter disease outcome. The non-random localization of tumor to specific anatomic sites suggests a strong dependence of tumor on the specific organ environment.

EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE LINKING THE PROSTATE CANCER MICROENVIRONMENT TO DISEASE PROGRESSION IN BONE AND RESISTANCE TO THERAPY

The lack of enhanced efficacy with the earlier introduction of chemotherapy in prostate cancer progression previously described, along with the organ-specific progression of prostate cancer, led us to consider that properties of the bone microenvironment, shared in part with the prostate 24,25 may be central to the observed stage-dependent chemotherapy-response profile (Fig. 1).

Experimental data support the view that the properties of the microenvironment affect the epithelial components of cancers in diverse ways.26-29 For instance, physiologic prostate-derived microenvironments induce cellular differentiation of normal prostate glandular formations, while cancer-associated microenvironments promote carcinogenesis.30-34 Recent reports raise the possibility of an alternative explanation and suggest paracrine support of prostate cancer in bone may be primarily mediated by stromal elements.34-37 This concept is also supported by the observation that prostate stromal cells, harvested from sites adjacent to cancer, have growth-promoting effects on malignant epithelial cells.35 Others have demonstrated that in vivo, in bone metastases, osteoblasts promote prostate cancer progression, including castrate-resistant disease progression.24,25,33 These data further support the concept that cancer growth promotes crosstalk between prostate cancer cells in bone and is central to prostate cancer progression. More recently, analogous findings were reported from studies using a prostate cancer xenograft—a mixed-species model of bone development in which the epithelial compartment is human and the mesenchymal compartment is murine.36 These experimental observations reported in the literature infer that the tumor microenvironment, and therefore stromal-epithelial–interacting pathways, play a critical role in disease progression. Taken together, these observations provide the rationale for prioritizing the microenvironment as a therapy target.

PARACRINE PATHWAYS IN THE PROSTATE TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT

An increasing number of stromal-epithelial–interacting pathways have been associated with prostate cancer progression and likely account for many of its clinical features. Several lines of evidence indicate that pathways integral to bone or prostate development, as well as homeostasis, are implicated in prostate cancer progression when aberrantly activated. The concept that prostate cancer usurps these normal developmental and functional programs in carcinogenesis and progression provides a basis for the rational prioritization of these pathways for further study.

Androgen signaling was identified more than half a century ago as a principal contributor to prostate cancer progression and therefore as a legitimate therapy target. More recent findings suggest that androgen signaling may have a dual role: directly on the epithelium and indirectly through the stroma. Preclinical data have shown that the stromal androgen receptor in both the prostate gland and the bone also functions as a tumor promoter.37 Other data also support the concept that androgen receptor-expressing stromal cells are capable of supporting and stimulating the growth of androgen receptor-negative epithelial cells.37

Clinical data from ongoing studies of new agents suggest that there is a hierarchy among stromal-epithelial–interacting pathways and that optimum suppression of androgen signaling is a necessary component of molecularly targeted therapy for some patients. The importance of androgen signaling can be inferred from the efficacy of further androgen blockade with CYP-17 inhibition38 in cancers previously considered androgen-independent, which contrasts with the lack of reported efficacy of molecularly targeted therapies.9,39,40 CYP-17 (C17-20 lyase, C17 hydroxylase) is a key enzyme in the biosynthetic route of androgens enabling the conversion of precursors to androstenedione. CYP-17 Inhibition thus blocks androgen production not only from the gonads but the adrenals as well. There is also recent evidence to support intratumoral production of androgens and presence of CYP-17 expression.

Besides androgen signaling, several signaling pathways central to prostate and bone development are associated with or implicated in prostate carcinognesis.41 These include but are not limited to fibroblast growth factor, hedgehog, TGF-beta, integrins, Src, Wnt, and Notch (Table 2)42-57 These associations are consistent with the hypothesis that the paracrine pathways common to prostate and bone development are also involved in prostate carcinogenesis. The hedgehog signaling pathway, for example, plays critical roles during prostate development and was found to be activated and support cancer cell survival during prostate cancer progression.40,41 The clinical relevance of these observations in preclinical models can be inferred from evidence that thalidomide, an agent with anti-angiogenesis activity, exhibited clinical efficacy likely through inhibition of sonic hedgehog signaling in prostate cancer.45,46 This clinical observation, although implied by association, supports the idea that this bone- and prostate-development program may also be central to prostate cancer progression.

Table 2.

Tumor microenvironment targeting

| Microenvironment targeting strategy | Molecular target | Agent | Class | Clinical development status/Trial phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-angiogenesis | VEGF | Bevacizumab | mAb | II |

| Aflibercept | Recombinant fusion protein (VEGF Trap) | III | ||

| VEGFR (+other RTKs like PDGFR) | Sunitinib | Small-molecule inhibitors of RTKs | III II |

|

| Sorafenib | II | |||

| Imatinib mesylate | II | |||

| Vatalinib | II | |||

| Thalidomide | Not clarified-Immunomodulators | II | ||

| Lenalidomide | Thalidomide analogue-IMids | III | ||

| Integrin signaling networks | αν β3 integrin | MEDI-522 (Abegrin or Vitaxin) | Humanized mAb | II |

| αν integrin | CNTO 95 | mAb | II | |

| αν β3 αν β5 integrins | Cilengitide | Antagonist of αν β3 and αν β5 integrins | II | |

| Developmental pathways | ||||

| Bone development-related pathways | Src-family kinases | Dasatinib | Small molecule kinase inhibitor | III |

| AZD0530 | I/II | |||

| RANK ligand | Denosumab | mAb | III | |

| Endothelin receptor | Atrasentan | Selective antagonist | III | |

| Zibotentan | III | |||

| Hedgehog Signalling | GDC-0449 | Smoothened antagonist | II | |

| FGF family | TKI258 | FGF receptors | I/II | |

| Notch | MK0752 | NOTCH | I/II | |

| Androgen signalling | CYP17 | Abiraterone acetate | Irreversible inhibitor of CYP17 | III |

| AR | MDV3100 | Small molecule AR antagonist | I/II III |

|

| Signalling cross-talk with AR | mTOR | Temsirolimus | Rapamycin analogues | II |

| Everolimus | ||||

| Deforolimus | novel mTOR inhibitor | |||

| EGFR | Gefitinib | EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor | II | |

| IGF Receptor | CP-751,871 | mAb | II | |

| IMC-A12 | II | |||

| TGF-beta | TGF-beta | AP-11014, AP12009 | mAb | preclinical |

Overall Conceptual Framework of Paracrine Pathways in Prostate Cancer

Deciphering the role of the paracrine pathways implicated in the tumor microenvironment will lead to improved understanding of prostate cancer progression and resistance to therapy. In the model we propose, prostate cancer usurps pathways involved in development and function of prostate and bone in progression and resistance to therapy. We therefore reason that knowledge of developmental biology and physiology will contribute to the understanding of prostate cancer progression and resistance to chemotherapy and thus provide valuable insight into prostate cancer treatments.

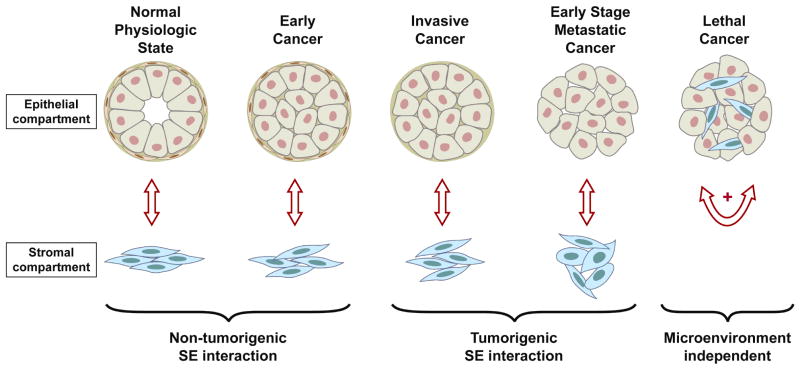

Our conceptual framework is based on the hypothesis that the properties of the prostate cancer microenvironment are important determining features in the clinical disease phenotype and its response to therapy. The evolution of prostate cancer—from a lesion with the morphologic features of cancer but with limited potential for progression to the potentially lethal form of the disease—has been attributed to a series of molecular events operating through adaptation and selection. For the purpose of this discussion, stroma comprises all nonepithelial components of the microenvironment. Paracrine interactions within the organ microenvironment ensure homeostasis in physiologic conditions: During early stages of carcinogenesis, the microenvironment contributes to the normal organ function and serves as a functional barrier to prostate carcinogenesis. Early disease lesions have the morphologic features of cancer but with limited potential for progression to the potentially lethal form of the disease. On disseminated disease progression, however, aberrant paracrine-pathway activation serves tumor growth, and the predominant microenvironment effect is to assist tumor survival. It is at those later stages of prostate cancer progression, when the tumor epithelium has become self-supporting and the pathways supporting its growth are sufficiently regulated within cancer cells, that the disease is indeed “epitheliocentric” (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Progressive exchanges in the tumor microenvironment (paracrine) interactions from the regulation of homeostasis, to the maintenance of this function in early neoplastic or preneoplastic lesions, through early invasion, to tumor-promoting effect in bone, and autonomous autocrine- (epitheliocentric-) driven progression not limited or restricted by a specific microenvironment.

As we previously mentioned, our proposed two-compartment model suggests that prostate cancer progresses through a paracrine, i.e., microenvironment-dependent phase to an autocrine phase that occurs later in the clinical course. This two-compartment model is able to account for the clinical observations described earlier in this discussion, given that progression through a paracrine phase (“microenvironment dependent”) precedes the autocrine phase of disease.

Our working hypothesis differs from the epitheliocentric view, i.e., autocrine, which attributes most aspects of progression, bone homing, and response and resistance to therapy to the malignant epithelial cells. Improved understanding of the stromal-epithelial–interacting signaling networks will be required to develop and apply effective combinations of molecularly targeted therapies. One possible explanation is that the molecular therapy is applied late in the progression of the disease when the heterogeneity of autocrine progression may be driving the biology. For instance, this may account for the limited patient benefit observed with the endothelin 1 receptor antagonist.54 A second possibility is that persistent paracrine androgen signaling contributes to the clinically observed resistance to inhibition of alternative signaling pathways. The latter could be addressed by developing markers reflecting the specific biology of disease in a particular patient. Addressing these possibilities will require earlier introduction of therapy with parallel monitoring of biomarkers that reflect the microenvironment. Management of the heterogeneity and unpredictability of the tumor microenvironment interactions will enhance development of treatment strategies that can efficiently screen for the effectiveness of the combination of molecularly targeted treatments. This is critical for maximal therapy efficacy. For example, preliminary evidence suggests that blockade of both platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can produce tumor remission.58 In addition, encouraging results with the use of the Src inhibitor dasatinib that blocks Src family kinases in both the epithelial and stromal compartments in combination with chemotherapy have been reported.59 These preliminary observations are consistent with the hypothesis that the use of combinations of agents that target stromal-epithelial– interacting pathways earlier in disease progression will be more efficacious. These two treatment options are being evaluated in ongoing phase III studies.

PROPOSED THERAPY PARADIGM AND IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY

Implementation of this therapy paradigm will require the development of biomarkers for disease state-specific therapies. This will also provide a framework for prioritizing candidate therapies targeting the tumor microenvironment. For example, in early disease states, the paradigm would provide the rationale for inhibiting progression by maintaining the functional barrier of the prostate microenvironment, a step we term “secondary prevention”. According to our hypothesis, cancers that exhibit evidence of microenvironmental remodeling are transitioning to a potentially lethal phenotype, and thus intervention with surgery or radiation may be effective in treating disease at this stage. Two examples of this are a decrease in the ratio of E-cadherin to matrix metalloproteinase expression in the malignant epithelium and an increase in the vascular density in the microenvironment, both of which have been strongly associated with disease progression.57

Cancers that have transitioned to more aggressive forms, i.e., by developing a bi-directional paracrine interaction, will be dependent on the microenvironment for their survival and proliferation. In comparison to other common solid cancers, the state at which prostate cancer becomes dependent on the microenvironment seems to persist longer. On the basis of clinical observations of treatment responses, the autocrine progression in other common solid cancers may occur much earlier, thus the microenvironment has a lesser role in defining the phenotype in those cancers.

The current understanding of the role of tumor microenvironmental factors in prostate cancer progression is limited and has prevented the development of successful therapy strategies for patients with advanced and castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Bone-homing radiopharmaceuticals that target both tumor cells and the bone microenvironment palliate patients’ symptoms and may affect the survival time of patients with metastases. Unfortunately, although the molecularly targeted therapies tested to date, including the selective endothelin A receptor antagonist atrasentan, the PDGF blocker imatinib, and the bone-resorption inhibitor zoledronic acid, were able to modify the bone microenvironment (as reflected by serial measurements of bone-turnover markers), they have not changed the course of the disease, at least in respect to serum concentrations of prostate-specific antigen.9,54,55,58

According to our hypothesis, combinations of agents targeting multiple factors that modulate the networks of signaling pathways involved in bone development should be prioritized for therapy development. Given that some signaling pathways are common to locally advanced cancers and early bone metastases, the therapeutic rationale may be extendable to subsets of patients with localized prostate cancer.17

Prompted by encouraging experimental data and preliminary results from ongoing phase II studies of inhibition of VEGF and Src,56 we have initiated phase III studies of this combinatorial strategy. The success of therapy based on this hypothetical paradigm will depend on the validation of specific biomarkers that reflect the microenvironment and will guide the development and application of this and other combinatorial molecular-targeting therapies.

TRANSLATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE.

The hypothesis that the tumor microenvironment is a determinate of chemotherapy resistance in prostate cancer emerges from the link between clinical and experimental observations. If we are able to validate this hypothesis, it will form the foundation for integration of microenvironment-targeted therapy into the treatment options for prostate cancer.

Footnotes

This manuscript contains original material that has not been previously presented in whole or in part.

References

- 1.Yagoda A, Petrylak D. Cytotoxic chemotherapy for advanced hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 1993;71(3 suppl):1098–109. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1098::aid-cncr2820711432>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross RW, Beer TM, Jacobus S, et al. A phase 2 study of carboplatin plus docetaxel in men with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer who are refractory to docetaxel. Cancer. 2008;112:521–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrero JM, Chamorey E, Oudard S, et al. Phase II trial evaluating a docetaxel-capecitabine combination as treatment for hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:738–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marur S, Eliason J, Heilbrun L, et al. Phase II trial of oral capecitabine (C) and weekly docetaxel (D) in patients with metastatic androgen independent prostate cancer (AIPC) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):5121. abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millikan RE, Wen S, Pagliaro LC, et al. Phase III trial of androgen ablation with or without three cycles of systemic chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5936–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackler NJ, Pienta KJ, Dunn RL, et al. Phase II evaluation of oral estramustine, oral etoposide, and intravenous paclitaxel in patients with hormone-sensitive prostate adenocarcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2007;5:318–22. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2007.n.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathew P, Thall PF, Bucana CD, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor inhibition and chemotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5816–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahut WL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, et al. Randomized phase II trial of docetaxol plus thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2532–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chi KN, Chin JL, Winquist E, et al. Multicenter phase II study of combined neoadjuvant docetaxel and hormone therapy before radical prostatectomy for patients with high risk localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008;180:565–70. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pettaway CA, Pisters LL, Troncoso P, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and hormonal therapy followed by radical prostatectomy: Feasibility and preliminary results. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1050–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Febbo PG, Richie JP, George DJ, et al. Neoadjuvant docetaxel before radical prostatectomy in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5233–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain M, Smith D, El-Rayes B, et al. Neoadjuvant docetaxel and estramustine chemotherapy in high-risk/locally advanced prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;61:774–80. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreicer R, Magi-Galluzzi C, Zhou M, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant docetaxel before radical prostatectomy for locally advanced prostate cancer. Urology. 2004;63:1138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shepard DR, Dreicer R, Garcia J, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel in high risk patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2009;181(4):1672–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eastham JA, Kelly WK, Grossfeld GD, et al. Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 90203: A randomized phase 3 study of radical prostatectomy alone versus estramustine and docetaxel before radical prostatectomy for patients with high-risk localized disease. Urology. 2003;62(suppl 1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt JD, Gibbons RP, Murphy GP, Bartolucci A. Adjuvant therapy for clinical localized prostate cancer treated with surgery or irradiation. Eur Urol. 1996;29(4):425–33. doi: 10.1159/000473791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Halford S, Rigg A, et al. Adjuvant mitoxantrone chemotherapy in advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2000 Oct;86(6):675–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tu SM, Millikan RE, Mengistu B, et al. Bone-targeted therapy for advanced androgen-independent carcinoma of the prostate: A randomised phase II trial. Lancet. 2001;357:336–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu SM, Kim J, Pagliaro LC, et al. Therapy tolerance in selected patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer following strontium-89 combined with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7904–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris MJ, Pandit-Taskar N, Stephenson RD, et al. Phase I study of docetaxel (Tax) and 153Sm repetitively administered for castrate metastatic prostate cancer (CMPC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl) abstr 5001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu S, Jones D, Mathew P, et al. Phase I study of concurrent weekly docetaxel (Tax) and repeated 153Sm-lexidronam (Sam) in androgen-independent prostate cancer (AIPC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5393. abstr 5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logothetis CJ, Navone NM, Lin SH. Understanding the biology of bone metastases: Key to the effective treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1599–602. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung LW, Huang WC, Sung SY, et al. Stromal-epithelial interaction in prostate cancer progression. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2006;5:162–70. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2006.n.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ingber DE. Can cancer be reversed by engineering the tumor microenvironment? Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:356–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joyce JA. Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albini A, Sporn MB. The tumour microenvironment as a target for chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:139–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes—bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunha GR, Fujii H, Neubauer BL, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in prostatic development: I. Morphological observations of prostatic induction by urogenital sinus mesenchyme in epithelium of the adult rodent urinary bladder. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1662–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunha GR, Donjacour AA, Cooke PS, et al. The endocrinology and developmental biology of the prostate. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:338–62. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-3-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung LW, Zhau HE, Ro JY. Morphologic and biochemical alterations in rat prostatic tumors induced by fetal urogenital sinus mesenchyme. Prostate. 1990;17:165–74. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung LWK. Fibroblasts are critical determinants in prostatic cancer growth and dissemination. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:263–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00050797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayward SW, Wang Y, Cao M, et al. Malignant transformation in a nontumorigenic human prostatic epithelial cell line. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuxhorn JA, Ayala GE, Rowley DR. Reactive stroma in prostate cancer progression. J Urol. 2001;166(6):2472–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li ZG, Mathew P, Yang J, et al. Androgen receptor-negative human prostate cancer cells induce osteogenesis in mice through FGF9-mediated mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2697–2710. doi: 10.1172/JCI33093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niu Y, Altuwaijri S, Lai KP, et al. Androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor and proliferator in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804700105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Attard G, Reid AH, Olmos D, de Bono JS. Antitumor activity with CYP17 blockade indicates that castration-resistant prostate cancer frequently remains hormone driven. Cancer Res. 2009;69(12):4937–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carducci MA, Saad F, Abrahamsson PA, et al. A phase 3 randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of atrasentan in men with metastatic hormonerefractory prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1959–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin AM, Rini BI, Weinberg V, et al. A phase II trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with biochemical relapse of prostate cancer after definitive local therapy. BJU Int. 2006;98:763–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey JM, Singh PK, Hollingsworth MA. Cancer metastasis facilitated by developmental pathways: Sonic hedgehog, Notch, and bone morphogenic proteins. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:829–39. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. FGF signaling in prostate tumorigenesis—new insights into epithelial-stromal interactions. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:495–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acevedo VD, Gangula RD, Freeman KW, et al. Inducible FGFR-1 activation leads to irreversible prostate adenocarcinoma and an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:559–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Memarzadeh S, Xin L, Mulholland DJ, et al. Enhanced paracrine FGF10 expression promotes formation of multifocal prostate adenocarcinoma and an increase in epithelial androgen receptor. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:572–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, et al. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–12. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez P, Hernández AM, Stecca B, et al. Inhibition of prostate cancer proliferation by interference with SONIC HEDGEHOG-GLI1 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12561–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404956101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Efstathiou E, Troncoso P, Wen S, et al. Initial modulation of the tumor microenvironment accounts for thalidomide activity in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1224–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon JA, Sodek J, Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Bone sialoprotein stimulates focal adhesion-related signaling pathways: role in migration and survival of breast and prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107(6):1118–2. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones E, Pu H, Kyprianou N. Targeting TGF-beta in prostate cancer: therapeutic possibilities during tumor progression. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13(2):227–34. doi: 10.1517/14728220802705696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang S, Pham LK, Liao CP, Frenkel B, Reddi AH, Roy-Burman P. A novel bone morphogenetic protein signaling in heterotypic cell interactions in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(1):198–205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feeley BT, Gamradt SC, Hsu WK, et al. Influence of BMPs on the formation of osteoblastic lesions in metastatic prostate cancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(12):2189–99. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maple H, Dasgupta P. The role of ‘notch’ in urological cancers. BJU Int. 2009;104(1):1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chi KN, Bjartell A, Dearnaley D, et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: From new pathophysiology to new treatment targets. Eur Urol. 2009;56(4):606–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carducci MA, Saad F, Abrahamsson PA, et al. A phase 3 randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of atrasentan in men with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1959–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin AM, Rini BI, Weinberg V, et al. A phase II trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with biochemical relapse of prostate cancer after definitive local therapy. BJU Int. 2006;98:763–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park SI, Zhang J, Phillips KA, et al. Targeting SRC family kinases inhibits growth and lymph node metastases of prostate cancer in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3323–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuniyasu H, Ukai R, Johnston D, et al. The relative mRNA expression levels of matrix metalloproteinase to E-cadherin in prostate biopsy specimens distinguishes organ-confined from advanced prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guérin O, Formento P, Lo Nigro C, et al. Supra-additive antitumor effect of sunitinib malate (SU11248, Sutent®) combined with docetaxel: A new therapeutic perspective in hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:51–7. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bajaj GK, Zhang Z, Garrett-Mayer E, et al. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate in patients with prostate cancer with evidence of biochemical relapse after definitive radical retropubic prostatectomy or radiotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]