Abstract

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) are very relevant pathologies among elderly people (≥ 65 y old), with a consequent high disease burden. Immunization with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) has been differently implemented in the Italian regions in the past years, reaching overall low coverage rates even in those with medical indications. In 2010, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) became available and recommended in the universal Italian infant immunization program. Since October 2012, indications for use of PCV13 were extended to subjects ≥ 50 y to prevent invasive pneumococcal diseases. The Italian decision makers should now revise regional indications for the prevention of pneumococcal diseases in the elderly. Pharmaco-economic analyses represent a useful tool to value the feasibility of new immunization programs and their sustainability. Therefore, an ad hoc population model was developed in order to value the clinical and economic impact of an adult pneumococcal vaccination program in Italy.

Particularly, different immunization scenarios were modeled: vaccination of 65 y-olds (1 cohort strategy), simultaneous vaccination of people aged 65 and 70 y (double cohort strategy) and, lastly, immunization of people aged 65, 70 and 75 y (triple cohort strategy), thus leading to the vaccination of 5, 10 and 15 cohorts during the 5 y of the program. In addition, the administration of a PPV23 dose one year after PCV13 was evaluated, in order to verify the economic impact of the supplemental serotype coverage in elderly people. The mathematical model valued the clinical impact of PCV13 vaccination on the number of bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (BPP) and pneumococcal meningitis (PM) cases, and related hospitalizations and deaths. Although PCV13 is not yet formally indicated for the prevention of pneumococcal CAP by the European Medicine Agency (differently from FDA, whose indications include all pneumococcal diseases in subjects ≥ 50 y), the model calculated also the possible impact of vaccination on CAP cases (non-bacteraemic), considering the rate of this disease due to S. pneumoniae. The results of the analysis show that, in Italy, an age-based PCV13 vaccination program in elderly people is cost-effective from the payer perspective, with costs per QALY ranging from 17,000 to 22,000 Euro, according to the adopted vaccination strategy. The subsequent PPV23 offer results in an increment of costs per QALY (from 21,000 to 28,000 Euro, according to the vaccination strategy adopted). Pneumococcal vaccination using the conjugate vaccine turned out to be already favorable in the second year of implementation, with incremental costs per QALY comparable to those of other already adopted prevention activities in Italy (for instance, universal HPV vaccination of 12 y-old girls), with further benefits obtained when extending the study period beyond the 5-y horizon of our analysis.

Keywords: pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, elderly, economic evaluation, cost-effectiveness, pneumococcal disease

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) are common pathologies among elderly people, with a high disease burden for both the National Health Service (NHS) and the society. In Italy, administration of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) is currently recommended to high-risks groups to prevent IPD in subjects with specific comorbidities.1 However, in Italy the PPV23 coverage is currently extremely low.

A 13-valent polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (PCV13) (Prevenar® 13, Pfizer Vaccines) became available in Italy 2 y ago with indication for protection against S. pneumoniae diseases (invasive disease, pneumonia and acute otitis media) in children aged 2 mo-5 y,2 with different regional implementation and vaccination coverage. Since October 2011, indications were extended to subjects ≥ 50 y to prevent IPD (European Medicine Agency, EMA) or all pneumococcal diseases (Food and Drug Administration indication, FDA).

Italian decision-makers are challenged on how to update recommendations for use of pneumococcal vaccination in adults. Evaluating whether an age-based vaccination program with PCV13 for elderly people may prove advantageous from both a clinical and economic perspectives for the National and Regional Health Services is a very up-to-date issue. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, pharmaco-economic analyses represent useful tools for health authorities and are required to value the feasibility of new immunization programs in a setting of limited economic health resources.3

Our study aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of age-based vaccination scenarios with PCV13 in a limited time frame (5 y) in subjects aged ≥ 65 y using the perspective of the NHS.

Results

The number of cases of PM, BPP and CAP avoided in 5 y since implementation of PCV13 vaccination, compared with a no-vaccination scenario, are reported in Table 1. According to PCV13 efficacy data, the biggest impact of vaccination regarding absolute number of cases is due to CAP reduction, while, in relative terms, it is related to BPP and PM diseases. The administration of an additional PPV23 dose increased the serotype coverage for invasive diseases by 13.9%, thus increasing the number of prevented cases. The number of deaths avoided after the introduction of pneumococcal vaccination is shown also in Table 1. The number of avoided deaths has a trend similar to the prevented cases of pneumococcal diseases.

Table 1. Avoided cases and deaths, and reduction rate (%) following the adoption of the vaccination program in 5 y vs. non-vaccination scenario.

| PCV13 | Cases avoided | Reduction rate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

|

| Hospitalized CAP cases | 1,646 | 3,112 | 4,323 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Non-hospitalized CAP cases | 3,529 | 6,674 | 9,270 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia cases | 303 | 572 | 1,197 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| Pneumococcal meningitis cases | 71 | 134 | 198 | 6 | 12 | 18 |

| Total cases | 5,548 | 10,492 | 14,988 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| PCV13 + PPV23 | Cases avoided | Reduction rate (%) | ||||

| 1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

|

| Hospitalized CAP cases | 1,646 | 3,112 | 4,323 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Non-hospitalized CAP cases | 3,529 | 6,674 | 9,270 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia cases | 329 | 623 | 1,303 | 7 | 5 | 10 |

| Pneumococcal meningitis cases | 77 | 145 | 214 | 7 | 13 | 19 |

| Total cases | 5,580 | 10,553 | 15,110 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| PCV13 | Deaths avoided | Reduction rate (%) | ||||

| 1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

|

| CAP cases | 310 | 587 | 816 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia cases | 28 | 53 | 131 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Pneumococcal meningitis cases | 13 | 25 | 44 | 5 | 9 | 16 |

| Total cases | 351 | 665 | 991 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| PCV13 + PPV23 | Deaths avoided | Reduction rate (%) | ||||

| 1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

1 cohort/ year |

2 cohorts/ year |

3 cohorts/ year |

|

| CAP cases | 310 | 587 | 816 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia cases | 30 | 57 | 143 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pneumococcal meningitis cases | 14 | 27 | 47 | 5 | 10 | 17 |

| Total cases | 355 | 671 | 1.006 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

As a consequence of the avoided pneumococcal disease cases, the adoption of an age-based immunization strategy with PCV13 yields savings ranging from 7 million to 19 million Euro. The administration of an additional dose of PPV23 gives a marginal increase of savings. According to the above assumptions, the modeled immunization strategies cost 91–241 million Euro in 5 y. Adding the administration of a dose of PPV23, the overall immunization campaign cost increases to 114–303 million Euro (Table 2).

Table 2. Savings/costs, net costs and ICERs obtained with the population model in 5 y of follow-up (costs and savings expressed in Euro).

| PCV13 | 1 cohort/year | 2 cohorts/year | 3 cohorts/year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health savings | 6,785,918 | 12,846,781 | 19,346,080 |

| Vaccination costs | 90,887,509 | 168,719,884 | 241,307,723 |

| Vaccination net costs | 84,101,591 | 155,873,103 | 221,961,644 |

| Costs / avoided cases | 15,158.93 | 14,857.06 | 14,809.35 |

| Costs / LYG | 12,783.03 | 14,363.40 | 16,213.89 |

| Costs / QALY | 16,987.33 | 19,289.34 | 22,109.42 |

| PCV13 + PPV23 | 1 cohort/year | 2 cohorts/year | 3 cohorts/year |

| Health savings | 6,985,556 | 13,228,692 | 20,005,336 |

| Vaccination costs | 114,407,827 | 212,632,744 | 303,189,701 |

| Vaccination net costs | 107,422,271 | 199,404,052 | 283,184,366 |

| Costs / avoided cases | 19,249.99 | 18,894.74 | 18,741.67 |

| Costs / LYG | 16,171.52 | 18,198.38 | 20,428.15 |

| Costs / QALY | 21,493.32 | 24,443.04 | 27,865.63 |

The net costs of PCV13 vaccination strategies, calculated as the difference between immunization costs and health savings due to the clinical cases avoided amount to 84 million Euro in the single-cohort strategy, 156 million Euro in the double-cohort strategy and 222 million Euro in the triple-cohort strategy. These values increase to 107, 199 and 283 million Euro, respectively, in the additional PPV23 administration scenario. Particularly, vaccination of 1 cohort per year determines a cost/QALY of 16,987 Euro, immunization of 2 cohorts per year 19,289 Euro and, lastly, of 3 cohorts per year 22,109 Euro, respectively. The cost/QALY increases to 21,493, 24,443 and 27,866 Euro, respectively, including the sequential PCV13+PPV23 immunization (Table 2).

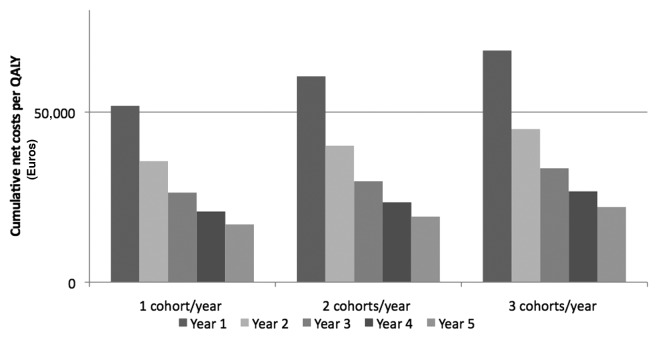

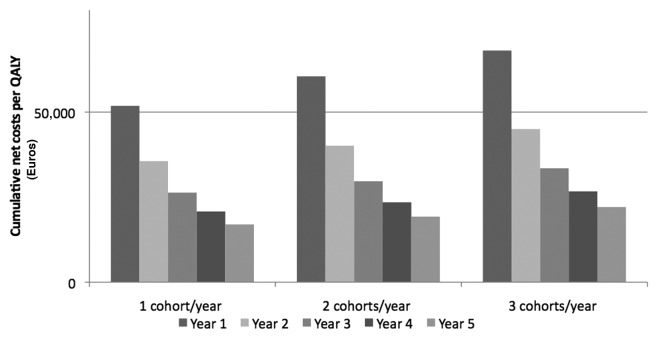

Considering cumulative net costs/QALY, pneumococcal vaccination of elderly subjects in Italy is already economically justified during the second year of immunization, independently from the adopted strategy (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative net costs (Euro) per QALY during the 5 y of analysis.

Sensitivity analysis brought no significant change in the overall profile of convenience of the three vaccination strategies (Table 3). The rate of CAP due to S. pneumoniae is the most relevant factor influencing the cost/QALY, but pneumococcal vaccination remained economically justified under all assumptions. Notably, outcomes were not particularly influenced by the reduction of PCV13 vaccination coverage (influencing both the number of avoided cases and vaccination costs).

Table 3. Cost (Euro) per QALY in the sensitivity analysis.

| Univariate Sensitivity Analysis: Cost/Qaly | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PCV13 | 1 cohort/year | 2 cohorts/year | 3 cohorts/year |

| CAP due to S. pneumonia: 24.3% | 27,325 | 31,042 | 35,092 |

| PCV13 vaccine efficacy: -10% | 19,348 | 21,974 | 25,199 |

| CAP, BPP, PM incidence: -10% | 19,002 | 21,581 | 24,748 |

| Vaccinated by GP: 50% | 17,588 | 19,974 | 22,781 |

| Base case scenario | 16,987 | 19,289 | 22,109 |

| PCV13 vaccination coverage: 50% | 16,987 | 19,289 | 22,109 |

| Hospitalized CAP cost: 3,286.82 Euro/case | 16,802 | 19,074 | 21,869 |

| Vaccine delivery cost/dose: 65–74 y: 2 euro; > 74 y: 1 euro | 16,595 | 18,843 | 21,671 |

| PCV13+PPV23 | 1 cohort/year | 2 cohorts/year | 3 cohorts/year |

| CAP due to S. pneumonia: 24.3% | 34,229 | 38,939 | 43,729 |

| PCV13 vaccine efficacy: -10% | 24,402 | 27,755 | 31,643 |

| CAP, BPP, PM incidence: -10% | 24,006 | 27,304 | 31,141 |

| Vaccinated by GP: 50% | 22,478 | 25,565 | 28,962 |

| Base case scenario | 21,493 | 24,443 | 27,866 |

| PCV13 vaccination coverage: 50% PPV23 vaccination coverage: 40% |

21,315 | 24,239 | 27,638 |

| Hospitalized CAP cost: 3,286.82 Euro/case | 21,310 | 24,230 | 27,628 |

| Vaccine delivery cost/dose: 65–74 y: 2 euro; > 74 y: 1 euro | 20,851 | 23,710 | 27,150 |

| PCV13 vaccination coverage: 50% PPV23 vaccination coverage: 30% |

20,240 | 23,010 | 26,268 |

| Multivariate Sensitivity Analysis: Cost/Qaly | |||

| PCV13 | 1 cohort/year | 2 cohorts/year | 3 cohorts/year |

| • CAP due to S. pneumonia: 24.3% • PCV13 vaccine efficacy: -10% • CAP, BPP, PM incidence: -10% • Vaccinated by GP: 50% |

35,803 | 40,684 | 45,813 |

| Base case scenario | 16,987 | 19,289 | 22,109 |

| • PCV13 vaccination coverage: 50% • Hospitalized CAP cost: 3.286,82 Euro/case • Vaccine delivery cost/dose: 65–74 y: 2 euro; > 74 y: 1 euro |

16,409 | 18,628 | 21,431 |

| PCV13 + PPV23 | 1 cohort/year | 2 cohorts/year | 3 cohorts/year |

| • CAP due to S. pneumonia: 24.3% • PCV13 vaccine efficacy: -10% • CAP, BPP, PM incidence: -10% • Vaccinated by GP: 50% |

45,111 | 51,332 | 57,306 |

| Base case scenario | 21,493 | 24,443 | 27,866 |

| • PCV13 vaccination coverage: 50% • PPV23 vaccination coverage: 30% • Hospitalized CAP cost: 3.286,82 Euro/case • Vaccine delivery cost/dose: 65–74 y: 2 euro; > 74 y: 1 euro |

19,483 | 22,143 | 25,391 |

Discussion and conclusions

S. pneumoniae diseases represent a relevant public health problem in Italy, with a steady increase of notified cases in the last decades (from 108 cases in 1994 to 851 in 2010), and with a considerable disease burden to the NHS, mostly due to hospitalization and deaths. Particularly, in the last years, pneumococcal diseases mainly involved subjects > 65 y. In 2009, 67% of notified cases were theoretically preventable by PCV13 vaccination and 82% by PPV23 immunization, according to serotype distribution of isolates.4 PCV13 replaced the previous PCV7 in the universal vaccination of children, recently receiving the indication for use in subjects > 50 y of age.5

In a period of extremely scarce health resources, a population model seemed particularly suitable to evaluate the impact of vaccination programs in a relatively short time frame. Namely, population models, differently from cohort models, allow us to estimate the impact of a new vaccine program on total population health during a fixed time period rather than focusing on a cohort.6-8

Population models are frequently adopted in economic evaluations of pneumococcal vaccination because they also include effects due to herd protection and serotype replacement after immunization.6 Those two issues were not approached in our model: studies on herd immunity after PCV13 vaccination of elderly subjects are not yet available. A protective effect on younger people and on unvaccinated elderly population might occur. However, should that be the case, the outcomes of the study would be even more favorable than reported in our simulation. However, as it was described after universal vaccination with PCV7 in children,9-13 also a partial serotype replacement might occur some years after the PCV13 vaccination of adults, thus potentially reducing the long-term effectiveness of vaccination. Such effect would anyway be very unlikely in the first 5 y since vaccination implementation. Therefore, we assumed that effects of herd protection and serotype replacement following vaccination were not relevant for the study.

The results of our evaluation show that vaccination of elderly people with PCV13 brings to a relevant reduction of pneumococcal diseases in 5 y. Considering clinical savings due to the implementation of PCV13 immunization, costs/QALY range from 17,000 to 22,000 Euro. PPV23 sequential administration causes a slight increment of cost/QALY. However, the values of cost/QALY stay largely under the threshold of 50,000 Euro, generally considered acceptable in economic studies. The only remark for the sequential use of conjugate-polysaccharide vaccines is the trade-off between potentially wider serotype coverage and potential effect of PPV23 on the memory B cell pool.14 Cumulative net cost/QALY are already favorable starting from the second year of implementation in all vaccination scenarios. In addition, ICERs are acceptable and comparable to those of other adopted prevention activities in Italy (i.e., HPV vaccination in female adolescent subjects).15 The uncertainty of input data values does not impact significantly on these encouraging outcomes in a one-way sensitivity analysis. Sequelae due to PM were not included in the analysis because usually they are rare in elderly people: the introduction of this health status in the model could even increase the favorable outcomes of the above assessment.

Since the cost-effectiveness profiles are immediately favorable even in the 3-cohorts strategy, the continuation of a one-cohort immunization program could be suggested after 5 y in order to maintain benefits for the future.

A limitation of our study is the assumption that PCV13 is effective against both IPD and CAP with the same efficacy detected in the pediatric population with PCV7. An efficacy study of PCV13 on CAP (CAPiTA Study) is ongoing in the Netherlands, and results are expected by the end of 2013.16

As a matter of fact, the extension of indication of the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine to the adult population is based on the comparative immunogenicity of PCV13 vs PPV23.2,5 It is useful to remind that also for the pediatric population, the substitution of PCV7 with PCV13 was based on immunogenicity data,2 also because it was deemed ethically unacceptable to perform clinical trials for new vaccines with a placebo arm in a situation of routine administration of a very effective vaccine. For this reason, since PCV13 effectiveness data in children are now corroborating the assumption of its efficacy both against IPD and pneumonia,17 it is reasonable to assume high efficacy against different pneumococcal diseases based on the excellent immunogenicity data provided by pre-licensure studies. Nevertheless, our assumptions will need to be verified in the light of effectiveness data progressively available in the next years.

Many economic studies demonstrated that PPV23 vaccination in the adult population was cost-effective, and in some cases a cost-saving strategy for the prevention of IPD.18 However, the new PCV13 could replace the first PPV23 immunization in subjects ≥ 65 y. The results of our study justify, even from the economic point of view, the implementation of PCV13 vaccination in the elderly, and confirm the cost-effectiveness of this preventive intervention, already recently adopted in the schedule of two Italian Regions (Puglia and Sicily).

In conclusion, the implementation of an age-based PCV13 immunization strategy of elderly people in Italy turned out to be already economically justified in the NHS perspective in the first 5 y of adoption. The program brings to an immediate favorable cost-effectiveness profile; further benefits can be expected extending the study period, due to the additional prevented pneumococcal disease cases.

Therefore, it is now time for health care decision maker to take advantage of this newly available tool for the improvement of health in the adult population.

Materials and Methods

Mathematical model

A population model was developed to value the clinical/economic impact of an age-based adult pneumococcal vaccination program with PCV13 in Italy during a 5-y period. The impact of PCV13 vaccination program was compared with a no-vaccination scenario because the current PPV23 coverage is very low and not homogenous throughout the country. The mathematical model was constructed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Particularly, three possible age-based PCV13 vaccination strategies were evaluated: immunization of 65 y-old subjects (single-cohort strategy), simultaneous vaccination of people aged 65 and 70 y (double-cohort strategy) and, lastly, simultaneous immunization of subjects aged 65, 70 and 75 y (triple-cohort strategy). The immunization program was assumed to last 5 y. Consequently, the 3 strategies (1, 2 or 3 age-cohorts) imply the overall immunization of 5, 10 and 15 cohorts, respectively. The clinical and economic impacts of those vaccination scenarios were evaluated on the entire Italian population aged ≥ 65 y. The administration of one dose of PCV13, without booster doses, was assumed.19 The additional impact of administration of a PPV23 dose, one year after PCV13, was evaluated. Therefore, 4, 8 and 12 cohorts of subjects would receive both PCV13 and PPV23 immunization in the 5-y analysis period, respectively.

The model forecasted the clinical impact of PCV13 vaccination on the number of IPD: bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (BPP) and pneumococcal meningitis (PM) cases, and related hospitalizations and deaths. The impact of vaccination on CAP morbidity, hospitalizations and deaths was assumed considering the rate of diseases due to S. pneumoniae. Figure 2 shows the decision tree used in conjunction with the population model.

Figure 2. Decision tree used in the analysis in conjunction with the population model.

The outcomes of the model include annual number of clinical cases, hospitalization and deaths related to CAP, BPP and PM with and without vaccination program, and number of avoided cases and rate of reduction due to immunization during the five years of analysis.

Furthermore, the model calculates annual clinical costs and the amount of net costs related to each immunization scenario. The main outcome measures were life-years gained (LYGs), quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

The analysis was performed according to the perspective of the NHS and did not take into account the direct non-medical costs and indirect costs associated with the loss of productivity due to S. pneumoniae diseases.

Epidemiological/clinical data

This study was performed on the resident population in Italy on January 1, 2011, grouped by age, as reported by the National Institute for Statistics (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, ISTAT).20 Only population aged ≥ 65 y was included in the study. After the first year of implementation of immunization strategies, the age groups ≥ 61 y were progressively involved in the vaccination offer when subjects became 65-y old.

Incidence, hospitalization rates and case fatality rates of CAP were obtained by Viegi et al.21 The overall rate of CAP due to S. pneumoniae was calculated to be 39.8%,22 assuming that such percentage is the same for hospitalized and non-hospitalized CAP cases.

Incidence and case fatality rates of BPP and PM by age were derived from a cost-effectiveness Italian study on PPV23 immunization in elderly people.23

Sequelae for meningitis were not included in the analysis: usually they are rare in adult subjects and the period of our analysis is short, determining a very limited economic impact.23,24

Lastly, although population models are used for the evaluation of pneumococcal vaccination strategies because they can include herd protection and serotype replacement effects,6 nevertheless those two effects were not included in the model, due to current lack of data in the adult population.

Vaccine data

Vaccination coverage of the targeted cohorts was supposed to be 60%, assuming the same average national coverage for the last annual influenza vaccination campaign in Italy in elderly subjects. In addition, 73.5% and 69.2% serotype coverage against pneumonia and IPD, respectively, were assumed for PCV13.25

A PCV13 efficacy of 94% was assumed for type-specific PM and 87.5% for pneumococcal pneumonia (bacteremic and non-bacteremic) in adult subjects, according to the data reported in clinical trials in children immunized with PCV7. While waiting for the availability of efficacy data of PCV13 in adults, the comparative immunogenicity data of PCV13 vs PPV23 in elderly subjects made such assumption the most reasonable. However, in order to account for a possible lower effectiveness in adults compared with children, a sensitivity analysis was performed on those parameters.2,16,26,27

Taking into account the supplemental PPV23 vaccination, 50% of vaccination coverage and 83.1% of serotype coverage were assumed.25 A steady value of efficacy against IPD (70%) during the 5-y time of the program was applied.23,28-30 Since efficacy of PPV23 on CAP has never been definitively proven, no impact of this vaccine on non-bacteremic pneumonia was assumed.31,32

Economic data

The cost of hospitalized CAP cases and BPP cases were obtained by the National Agency for Regional Health Services (AGENAS) and were calculated as average of Regional fare values in 2009.33 An outpatient CAP case costs 105 Euro, including antibiotic home treatment and specialist consultation (without general practitioners examination cost, independently paid by NHS).34 All BPP and PM cases were assumed to be hospitalized.23 The cost of a PM case as reported by Merito et al. was used in the analysis,23 because of lack of official data.

In Italy, the current price (2012) paid by the NHS for a PCV13 dose is 42.50 Euro, while it is approximately 16.00 Euro for PPV23. It was assumed that all vaccines are administered by health workers in the vaccination centers, except for 25% of the target population, that was assumed to be immunized by general practitioners. According to the current policies in Italy for the annual influenza vaccination program, the payment of an incentive to general practitioners for vaccine administration was foreseen in the model.23

In order to calculate LYGs values, an average life expectancy of 20 y was applied to 65 y-old subjects, as reported by the National Institute of Statistics in 2011.35 The QALYs gains after the introduction of immunization strategies were calculated applying the weights referring to average age-specific quality of life scores, CAP and IPD (the last two weights are reported only for the average specific number of hospitalization days: 11 and 34 d, respectively).28,30,36

A discount rate of 3% per year was applied to medical costs for the treatment of pneumococcal diseases cases, and to vaccination costs (including vaccine and delivery costs). However, no discounting was applied to life-years gained.

All input data used in the mathematical model in the base case scenario are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Input data in the population model (base case scenario).

| Clinical data | Values | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy at 65 y of age (years) | 20 | ISTAT website35 |

| CAP incidence > 64 y (per 1,000) | 3.34 | Viegi, 200621 |

| CAP hospitalization rate (%) | 31.8 | Viegi, 200621 |

| CAP case fatality rate (%) | 6.0 | Viegi, 200621 |

| CAP due to S. pneumonae (%) | 39.8 | Bewick, 201223 |

| BPP Incidence (per 100,000) | 65–74 y: 7.8 75–84 y: 19.9 > 84 y: 52.4 |

Merito, 200723 |

| PM Incidence (per 100,000) | 65–74 y: 1.7 75–84 y: 1.9 > 84 y: 0.8 |

Merito, 200723 |

| BPP case fatality rate (%) | 65–74 y: 9.2 75–84 y: 12.6 > 84 y: 37.0 |

Merito, 200723 |

| PM case fatality rate (%) | 65–74 y: 18.5 75–84 y: 29. 4 > 84 y: 39.4 |

Merito, 200723 |

| Vaccination data | ||

| PCV13 vaccination coverage (%) | 60 | as flu vaccination |

| PCV13 serotype coverage against pneumonia (%) | 73.5 | Schito, 201125 |

| PCV13 serotype coverage against IPD (%) | 69.2 | Schito, 201125 |

| PCV13 efficacy against pneumonia (%) | 87.5 | EMA, 20112 Black, 200026 Black, 200227 |

| PCV13 efficacy against PM (%) | 94 | EMA, 20112 Black, 200026 Black, 200227 |

| PPV23 vaccination coverage (%) | 50 | Assumption |

| PPV23 serotype coverage against IPD (%) | 83.1 | Schito, 201125 |

| PPV23 efficacy against IPD (%) | 70 | Merito, 200723 Sisk, 200328 Ament, 200029 Smith, 201230 |

| Cost data (Euro) | ||

| Cost discount rate (%) | 3 | |

| Hospitalized CAP cost/case | 2,680.85 | Age.na.s. website33 |

| Non-hospitalized CAP cost/case | 105 | Potena, 200834 |

| BPP cost/ case | 4,068.40 | Age.na.s. website33 |

| PM cost/case | 65–74 y: 19,114.99 > 74 y: 15,474.08 |

Merito, 200723 |

| PCV13 vaccine cost/dose | 42.50 | |

| PPV23 vaccine cost/dose | 16.00 | |

| Vaccine delivery cost by GP | 65–74 y: 5.76 > 74 y: 2.88 |

Merito, 200723 |

| Subjects vaccinated with PCV13 by GP | 0.25 | Assumption |

| Subjects vaccinated with PPV23 by GP | 0.25 | Assumption |

| Quality-adjusted life-years weights | ||

| Average age-specific quality of life | 65–70 y: 0.76 70–75 y: 0.74 75–80 y: 0.70 80–85 y: 0.63 |

Sisk, 200328 |

| IPD | 0.2 | Smith, 201230 n° hospitalization days: 34 Total weights: 0.02 |

| CAP | 0.2 | Smith, 201230 n° hospitalization days: 11 Total weights: 0.01 |

Note: CAP: Community-acquired pneumonia; BPP: bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia; PM: pneumococcal meningitis; IPD: invasive pneumococcal disease.

Sensitivity analysis

The rate of CAP cases due to S. pneumoniae was decreased from 39.8% to 24.3%, as reported in a meta-analysis study.37 In addition, PCV13 and PPV23 vaccination coverages were simultaneously lowered to 50% and 30%. The indirect effect of the childhood vaccination program with PCV13 on elderly subjects was not included in the analysis because of its recent and not uniform implementation in the country, and to the evidence that such indirect effect is only achievable with very high immunization coverage. However, in order to take into account a possible partial herd effect, the baseline incidence rates of CAP, BPP and PM were reduced by 10%. It was also speculated that 50% of the elderly cohorts were immunized by general practitioners (instead of 25%), with a related increment of delivery costs. Since PCV13 efficacy in children was applied to elderly subjects, a 10% reduction of vaccine efficacy against pneumonia and IPD was tested. The cost per case of hospitalized CAP was varied to the cost of therapy with levofloxacin, currently considered the most relevant treatment, amounting to 3,286.82 Euro/case.38 Lastly, only 2 and 1 Euro of incentive for general practitioners (depending from the age group) were modeled instead of full price.

In addition, a multivariate analysis was performed in order to explore the outcomes in terms of a “best” case and “worst” case scenario by simultaneously using the most favorable and unfavorable parameters for the vaccination program.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

One of the authors (S.B.) received a grant from Pfizer Italia to support a part-time researcher position.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/23268

References

- 1.Piano NPV. (PNPV) 2012-2014. Gazzetta Ufficiale n.47 (12 March 2012). Ministero della Salute. Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1721_allegato.pdf

- 2.Prevenar® 13, Pfizer Vaccines. Summary of product characteristic (20 December 2011). European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO). Vaccine introduction guidelines. Adding a vaccine to the national immunization programme. Decision and implementation. 2005. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2005/WHO_IVB_05.18.pdf

- 4.Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Dati di sorveglianza delle malattie batteriche invasive aggiornati al 24 febbraio 2012. Available at: http://www.simi.iss.it/files/Report_MBI.pdf

- 5.European Medicines Agency. Science Medicines Health. Assessment report Prevenar 13 pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (13-valent, adsorbed). CHMP variation assessment report Type II variation EMEA/H/C/001104/II/0028. Efficacy Study Results. 2011. Available at: http://www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Assessment_Report_-_Variation/human/001104/WC500119784.pdf

- 6.Standaert B, Demarteau N, Talbird S, Mauskopf J. Modelling the effect of conjugate vaccines in pneumococcal disease: cohort or population models? Vaccine. 2010;28(Suppl 6):G30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauskopf J. Meeting the NICE requirements: a Markov model approach. Value Health. 2000;3:287–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2000.34006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauskopf J. Prevalence-based economic evaluation. Value Health. 1998;1:251–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.1998.140251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, et al. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:32–41. doi: 10.1086/648593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poehling KA, Talbot TR, Griffin MR, Craig AS, Whitney CG, Zell E, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among infants before and after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA. 2006;295:1668–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steenhoff AP, Shah SS, Ratner AJ, Patil SM, McGowan KL. Emergence of vaccine-related pneumococcal serotypes as a cause of bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:907–14. doi: 10.1086/500941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Invasive pneumococcal disease in young children before licensure of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine - United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacman DJ, McIntosh ED, Reinert RR. Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in young children in Europe: impact of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and considerations for future conjugate vaccines. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clutterbuck EA, Lazarus R, Yu LM, Bowman J, Bateman EA, Diggle L, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate and plain polysaccharide vaccines have divergent effects on antigen-specific B cells. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1408–16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capri S, Bamfi F, Marocco A, Demarteau N. Impatto clinico ed economico della vaccinazione anti-HPV. Int J Public Health. 2007;4:S36–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hak E, Grobbee DE, Sanders EA, Verheij TJ, Bolkenbaas M, Huijts SM, et al. Rationale and design of CAPITA: a RCT of 13-valent conjugated pneumococcal vaccine efficacy among older adults. Neth J Med. 2008;66:378–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller E, Andrews NJ, Waight PA, Slack MP, George RC. Effectiveness of the new serotypes in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29:9127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogilvie I, Khoury AE, Cui Y, Dasbach E, Grabenstein JD, Goetghebeur M. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in adults: a systematic review of conclusions and assumptions. Vaccine. 2009;27:4891–904. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Roux A, Schmöle-Thoma B, Siber GR, Hackell JG, Kuhnke A, Ahlers N, et al. Comparison of pneumococcal conjugate polysaccharide and free polysaccharide vaccines in elderly adults: conjugate vaccine elicits improved antibacterial immune responses and immunological memory. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1015–23. doi: 10.1086/529142. [Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2008 May 1;46] [9] [:1488. Schmöele-Thoma, B ] [corrected to Schmöle-Thoma, B] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popolazione residente al 1 Gennaio 2011 per età, sesso e stato civile. Demo.istat. Demografia in cifre. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Available at: http://demo.istat.it

- 21.Viegi G, Pistelli R, Cazzola M, Falcone F, Cerveri I, Rossi A, et al. Epidemiological survey on incidence and treatment of community acquired pneumonia in Italy. Respir Med. 2006;100:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bewick T, Sheppard C, Greenwood S, Slack M, Trotter C, George R, et al. Serotype prevalence in adults hospitalized with pneumococcal non-invasive community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2012;67:540–5. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merito M, Giorgi Rossi P, Mantovani J, Curtale F, Borgia P, Guasticchi G. Cost-effectiveness of vaccinating for invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly in the Lazio region of Italy. Vaccine. 2007;25:458–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozenbaum MH, Hak E, van der Werf TS, Postma MJ. Results of a cohort model analysis of the cost-effectiveness of routine immunization with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine of those aged > or =65 years in the Netherlands. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1517–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schito GC, Fadda G, Nicoletti G, Debbia EA. Streptococcus pneumoniae isolati da malattie invasive e infezioni respiratorie in soggetti adulti e anziani (>50 anni) ospedalizzati in Italia: studio clinico-microbiologico retrospettivo. Giornale Italiano di Microbiologia Medica Odontoiatrica e Clinica. 2011;15:75–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR, et al. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:187–95. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black SB, Shinefield HR, Ling S, Hansen J, Fireman B, Spring D, et al. Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than five years of age for prevention of pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:810–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sisk JE, Whang W, Butler JC, Sneller VP, Whitney CG. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against invasive pneumococcal disease among people 50 through 64 years of age: role of comorbid conditions and race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:960–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ament A, Baltussen R, Duru G, Rigaud-Bully C, de Graeve D, Ortqvist A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination of older people: a study in 5 western European countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:444–50. doi: 10.1086/313977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith KJ, Wateska AR, Nowalk MP, Raymund M, Nuorti JP, Zimmerman RK. Cost-effectiveness of adult vaccination strategies using pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. JAMA. 2012;307:804–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moberley SA, Holden J, Tatham DP, Andrews RM. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD000422. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000422.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huss A, Scott P, Stuck AE, Trotter C, Egger M. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2009;180:48–58. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080734. [Erratum in: CMAJ. 2009 May 12;180] [10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agenzia Nazionale per i Servizi Sanitari Regionali. (Age.na.s.). Ricoveri ospedalieri, i sistemi tariffari regionali vigenti nell’anno 2009. Available at: http://www.agenas.it/index.htm

- 34.Potena A, Simoni M, Cellini M, Cartabellotta A, Ballerin L, Piattella M, et al. Management of community-acquired pneumonia by trained family general practitioners. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Speranza di vita alla nascita e a 65 anni, per sesso e regione – Anni 2008-2011. Demo.istat. Demografia in cifre. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Available at: http://demo.istat.it

- 36.Giusti M, Banfi F, Perrone F, Pitrelli A, Pippo L, Giuliani L. [Community-acquired pneumonia: a budget impact model] Infez Med. 2010;18:143–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.File TM., Jr. Streptococcus pneumoniae and community-acquired pneumonia: a cause for concern. Am J Med. 2004;117(Suppl 3A):39S–50S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazzaro C, Iori I, Gussoni G. Studio FASTCAP sulla gestione ospedaliera delle polmoniti acquisite in comunità: valutazione farmacoeconomica della fase prospettica. FASTCAP study on the management of hospitalizes patients with community-acquired pneumonia: pharmacoeconomic analysis of the prospective phase. Italian Journal of Medicine. 2008;2:55–66. [Google Scholar]