Abstract

Background

Women who have been in prison carry a greater lifetime risk of HIV for reasons that are not well understood. This effect is amplified in the Southeastern United States, where HIV incidence and prevalence is especially high among African American (AA) women. The role of consensual sexual partnerships in the context of HIV risk, especially same-sex partnerships, merits further exploration.

Methods

We conducted digitally recorded qualitative interviews with 29 AA women (15 HIV-positive, 14 HIV-negative) within three months after entry into the state prison system. We explored potential pre-incarceration HIV risk factors, including personal sexual practices. Two researchers thematically coded interview transcripts and a consensus committee reviewed coding.

Results

Women reported complex sexual risk profiles during the six months prior to incarceration, including sex with women as well as prior sexual partnerships with both men and women. Condom use with primary male partners was low and a history of transactional sex work was prevalent. These behaviors were linked to substance use, particularly among HIV-positive women.

Conclusions

Although women may not formally identify as bisexual or lesbian, sex with women was an important component of this cohort’s sexuality. Addressing condom use, heterogeneity of sexual practices, and partner concurrency among at-risk women should be considered for reducing HIV acquisition and preventing forward transmission in women with a history of incarceration.

Introduction

In the United States (US), the burden of HIV infection among women is disproportionately heavy among African American (AA) women, among whom HIV incidence is more than 15 times higher than white women. (Prejean et al., 2011) This disparity is particularly stark in the Southeastern US, where AA women accounted for 71% of new HIV infections among women in this region between 2005 and 2008. (Prejean et al., 2011) AA women are also more likely to be incarcerated compared to white and Latina women, an epidemic closely linked to HIV, and associated scourges of substance abuse, poverty, mental illness, and personal and community violence.(Greenfeld, 1999; Harlow, 1999; James, Glaze, & United States Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006; McClelland, Teplin, Abram, & Jacobs, 2002; Mumola, Karberg, & United States Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006; Rosen et al., 2009; Staton-Tindall, Royse, & Leukfeld, 2007) As a result, women who have been in prison carry a greater lifetime risk of HIV. (Staton-Tindall et al., 2011; Staton-Tindall, Leukefeld, et al., 2007) Among incarcerated AA women in North Carolina (NC), HIV is more than five times as prevalent as it is among the general population of AA women in NC.(North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2011; North Carolina Department of Public Safety, 2012)

Despite a “perfect storm” of convergent risk factors for HIV infection among AA women in prison, it remains unclear why some women involved with the criminal justice system are infected and others are not. While most AA women in the Southeastern US who contract HIV do so through heterosexual sex with men,(Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012) few data exist that describe the sexual relationships of women with involvement in the criminal justice system. Improved understanding of the sexual practices of these women may shed light on behaviors that increase or reduce HIV risk and appropriate targets for HIV prevention efforts. In addition, exploring the decision-making processes behind these women's sexual behaviors to include such issues as financial need, desire for children, and fear of violence may further illuminate aspects of their lives that put them at risk. We explored the contextual and relationship features of the pre-incarceration lives of AA women in the NC state prison system to better understand the factors that may influence their risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). We placed a particular focus on exploring experiences that might differentiate women who are HIV-positive from those who are HIV-negative.

Methods

We conducted face-to-face semi-structured qualitative interviews with 29 women (15 HIV-positive, 14 HIV-negative) who were incarcerated at one of two women’s prisons (one medium security, one maximum security) in the NC state prison system, the NC Department of Public Safety (NCDPS).

Eligibility criteria included: age 18 or older, self-identified AA race, English-speaking, and entering prison within the three months preceding the interview, to reduce recall bias regarding pre-incarceration experiences. Additionally, participants must have recent documentation of HIV status. We asked each participant for permission to audio record the interview; although refusal to do so did not exclude them from the study, all participants agreed to be recorded. A research assistant or an interviewer obtained written informed consent from all participants before collecting any data. Interviews were scheduled within two days of recruitment.

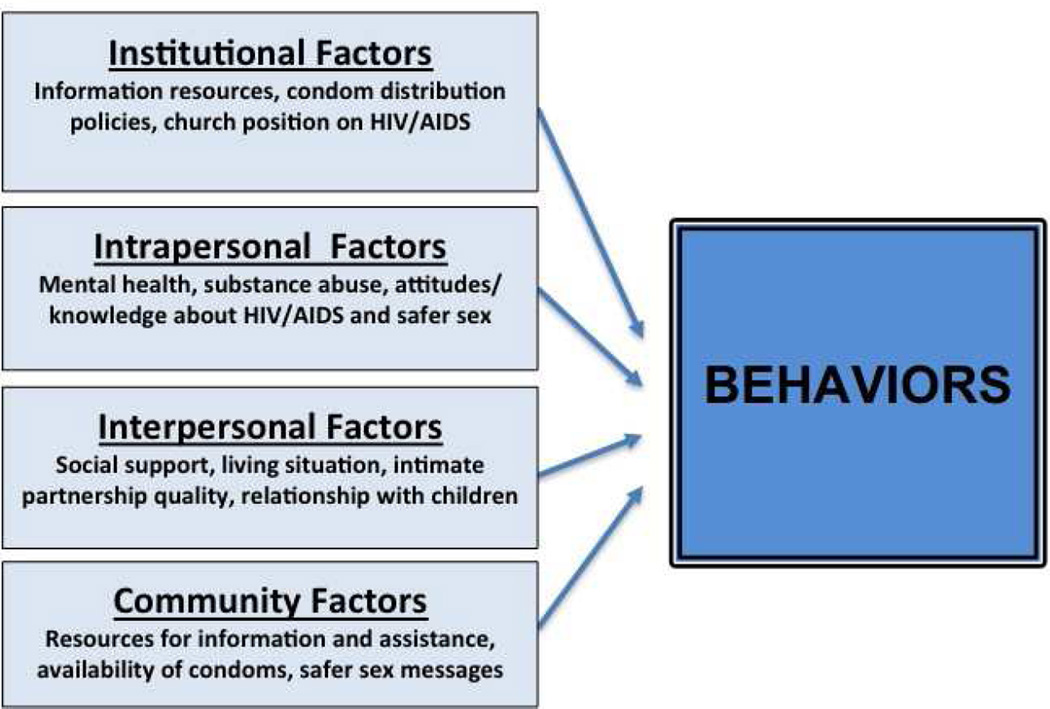

We developed the interview guide based on the Social Ecological Framework, a theoretical framework that recognized multiple levels of influence on health, including policy, institutional community, inter- and intra-personal levels (Figure 1).(McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988) Questions were designed to explore aspects of the women’s lives from each of these levels that had the potential to increased their exposure to HIV. (Table 1) We explored the participant’s sexuality and sexual practices and included questions related to important relationships and sexual encounters, transactional sex and condom use in the six months prior to prison entry. (Table 1)

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model: The Social Ecological Model of Behavior. Adapted from McLeroy et al. (1988)(McLeroy et al., 1988)

Table 1.

Examples of Questions used during Interviews

|

Between May 2011 and January 2012 two interviewers conducted 29 interviews in private rooms at the two prisons without correctional officers present. Both interviewers were trained in conduct of research in criminal justice settings and use of qualitative methods.

Data analysis followed a multi-stage, iterative process. Digital recordings of the interviews were uploaded to a secure server and professionally transcribed. Transcript files were entered into NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 9, 2010). Two researchers thematically coded each interview transcript and a consensus committee comprised of researchers from the schools of medicine, public health, and social work met regularly to review coding. As major emerging themes were identified, a subgroup of researchers examined transcript coding for consistency and reviewed discrepancies. The Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and the NCDPS Human Subjects Research Committee approved the procedure of this study. We also obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

In our categorization of sexual behaviors, participants who reported male sexual partners exclusively in the six months prior to incarceration but female partners prior to that time were categorized as having male and female sexual partners. Participants who reported exclusively female partners in the six months prior to incarceration were categorized as having female sexual partners even if they had ever had sex with a male partner. This system was designed to capture the variety of sexual practices in a population more inclined to report behaviors rather than a sexual identity.

Results

Characteristics of study participants are detailed in Table 2. HIV-positive participants tended to be older than HIV-negative participants. Refusal rates were similar during screening between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants, less than 10%. Participants most commonly cited time constraints as reason for refusal.

Table 2.

Characteristics of HIV-Positive1 and HIV-Negative Participants (n = 29)

| HIV-positive (n=15) |

HIV-negative (n=14) |

Total (n=29) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 37.8 (24–60) | 29.9 (19–41) | 34.0 (19–60) |

| Number of prior NC incarcerations, mean (range) | 3.8 (1–9) | 1.9 (1–8) | 2.9 (1–9) |

| Transactional sex2 | 10 (67%) | 4 (29%) | 14 (48%) |

| Biological children | 14 (93%) | 9 (64%) | 23 (79%) |

| Sexual Partner gender | |||

| Male | 11 (73%) | 7 (50%) | 18 (62%) |

| Male and Female3 | 4 (27%) | 3 (21%) | 7 (24%) |

| Female | 0 | 4 (29%) | 4 (14%) |

Results of prison entry HIV testing

Defined as ever having exchanged sexual acts in for money, drugs, housing, goods, or survival

Participants who reported male partners in the past 6 months but female partners (outside of prison) prior to that were included in this category.

Complex sexuality and diversity of lifetime sexual practices prior to incarceration were observed within the interview transcripts. Three prominent themes emerged as critical for understanding the context of HIV/STI risk among these women: sex with other women, selective condom use, and transactional sex. Each of these is described below and illustrated through select interview excerpts.

Sex with other women

A substantial proportion of women reported a history of sex with women or primarily female sexual partnerships outside of prison. Four of 29 women reported sex with female partners exclusively in the six months prior to incarceration (WSW) and seven others reported sex with both men and women in the past but only male partners in the six months prior to incarceration (WSMW). Participants were not specifically asked about sexual identity, however, one woman described herself as lesbian, one as gay, and one as bisexual. Nineteen out of 29 women, including two WSW and six WSMW, had biological children.

Four of the seven WSMW and none of the WSW were HIV-positive. All participants described worrying about HIV and STIs at some point in their adult lives, although participants in exclusive partnerships with women indicated that this was not an everyday concern. Most WSW acknowledged that their female partners also had male partners intermittently. A few WSW expressed relief that they had not contracted HIV or STIs in their past relationships with men but were not concerned about this risk in their relationships with women.

One 41-year-old woman’s description of her relationships with both men and women throughout her life reflect the evolution of her sexual identity as well as her decision to forgo future relationships with men. This was based not only on her identification as gay but also due to feelings of betrayal after a relationship with a man ended:

Interviewee: My mother has been giving me a hard time about being gay. I think I’ve been gay all my life, I just always tried to please someone else, like my oldest two children have the same father … I was with their dad, and when we broke up I was with a girl … [after which] I was with another girl, like four and a half years. Then I met my son’s father – the most beautiful relationship I ever had with a man. But he cheated on me and it hurt me so deeply … that I just could not get past it.

So I even tried for a whole year to mend the relationship, because he was truly a good man. But I couldn’t, and after him was another girl. And I don’t think I want to try men again. So I may – by the grace of God, I don’t have HIV or any uncurable diseases, hepatitis, I mean herpes or syphilis, I don’t have any of that, thank God. I’ve been fortunate … But I don’t think I’ll ever be with another man. He hurt me really, really, really badly.

Importantly, this participant reflects on “being gay all my life” but reports having three children in two different relationships with men - a consistent theme in the lives of the WSW and WSMW in our cohort.

Another participant, a 33-year-old HIV-negative woman with children, recounted sexual relationships with a male partner and a female partner concurrently in the six months before incarceration. These concurrent partnerships mirrored those of her sexual partners: she was aware of another woman her boyfriend was having sex with as well as her girlfriend’s male and female partners:

Interviewer: Did you know if [your girlfriend] had other sexual partners, either male or female?

Interviewee: Yes.

…

Interviewer: Okay. Tell me about any other people you think she was having sex with.

Interviewee: I know the female she was with, she was with her for like five years, and I know her boyfriend.

Participants with primarily female sexual partners tended to view their risk of STIs as low. These perceptions were primarily justified by the following rationale: being with the same partner for a long period of time, being monogamous with that partner and/or believing that sex with women was “safe” as compared to sex with men. For example, a 36-year-old HIV-negative participant related her sexual history before incarceration as follows:

Interviewee: I haven't been with anybody. I don't really – I just – well, I being with one person for 13 years, and we haven't had any sexual – not no diseases or anything that I know of that – well, she hasn't and I haven't. It's a girl. I've been with her for 13 years.

When asked about her future risk for STI, a 25-year-old HIV-negative woman responded:

Interviewee: Nothin' too much really, 'cause you really get many sexually transmitted diseases from men and men is not my thing anymore.

Interviewer: What has put you at risk in the past?

Interviewee: Well in the past, let me see. I only had one sexually transmitted disease and it was trichinosis or whatever you call that … And since then, I never will ever sleep with a man again unprotectedly. So I do want kids one day, so I'm not saying that I'd never sleep with a man again, but I would make sure that we go and get tested first.

The same participant described her sexual identity as follows:

Interviewee: I'm a lesbian female. I've been a lesbian, I'd say, for about ten years, and it's just my choice and preference, and I haven't been with a man in about ten years also.

Similar to the other participants described above, this participant described a complex social network in her household that included her relationship with her current partner, who has sex with both men and women:

Interviewee: Okay. I live with my girlfriend, and my girlfriend has a husband. So her husband has his own girlfriend and his girlfriend has kids, and we all live in the same house.

The 33-year-old HIV-negative woman with male and female partners described above related her decision-making process regarding barrier protection with both partners:

Interviewer: So [your girlfriend] had both … male and female partners. What made it difficult to use condoms or protection, such as a dental dam … do you know what I mean by a dental dam?

Interviewee: Yeah.

Interviewer: For oral sex.

Interviewee: Yes. I guess you never think about it at the time. I guess a lot of people think you can’t get diseases orally.

Many study participants reported their sexual partners’ concurrent partnerships more commonly than they reported their own and related how these relationships put the participant at risk for STIs or HIV. One HIV-negative participant, a 29-year old with an eight-year-old child, reported a long-term relationship with a woman since her relationship with her child’s father ended. She expressed dismay regarding an STI diagnosis and suspected that her girlfriend had a male partner:

Interviewee: And we had a fellow what visited that I always question it, especially when I got trichomoniasis. It had to come from her 'cause I was in a rehab for a while. And I got tested when I went in for all this and I didn't have it until I got out from rehab. Then I had it.

Interviewer: Okay. And what did you think when you learned that you had trich?

Interviewee: I was upset, scared.

Interviewer: How old were you?

Interviewee: I was 27 … 'Cause it was kinda – I haven't – I did – I haven't had sex with a male since the birth of my daughter and she's 8.

Selective condom use

We asked participants about condom use for sexual encounters in the six months before incarceration (see Table 1, Questions 5b–e). Although not asked directly, most participants indicated that they were aware of the benefits of the male condom in prevention of pregnancy and HIV and other STIs and seemed to value these potential benefits highly, particularly among those who were HIV-positive. The following quote is from a 60-year-old HIV-positive woman with five children who describes her commitment to condoms after discovering she had HIV, which she suspected she had contracted from her boyfriend of 16 years:

Interviewee: My children and my grandchildren, my nieces, my nephews and the little young boys that be out there up and down the street, if they holler they got a girlfriend, I go in the house and give them a handful of condoms. And they say …“Why you being like that, why you giving me them?” I say “First of all there’s too many diseases out there for you to get, second you don’t want no baby at no early age and you’re trying to go to school.” I said, “Now, you have your choice, stay healthy, stay in school, and stay alive.”

Overall, however, our study population reported very low male condom use with primary male partners and no barrier protection use with female partners. Many women reported using condoms with more casual male partners but not generally with more committed partners or with the fathers of their children. Participants reported three main factors that they considered when making decisions about whether or not to use condoms: 1) How much they could “trust” their partner, a word that encompassed emotional trust as well as an assumption that both partners were monogamous and free of HIV/STI or that HIV/STI status had been disclosed, 2) their desire for children or lack of opposition to becoming pregnant, and/or 3) deferring to a male partner’s preference.

For example, one 28-year-old HIV-negative woman with both male and female sexual partners related that she based her decision-making about whether to use condoms or not with male partners on her perception of exclusivity in the relationship. She refers to her male sexual partner outside of her relationship with her boyfriend as her “friend”:

Interviewee: With my boyfriend, we use a condom most of the time. With my friend, we used a condom all the time because he has a girlfriend.

Another participant, a 33-year-old HIV-negative woman with both male and female sexual partners in the six months before incarceration described her decision to stop using condoms with her primary male partner as one based on trust:

Interviewee: I think I never used a condom with him, 'cause we was together for so long, but at first, when we first started dating, I used a condom every time.

…

Interviewer: So seven months into the relationship is when you began to have unprotected sex, and what made you have unprotected sex?

Interviewee: I felt like that I could trust him then, that he was just with me and nobody else.I don't know what else. I just felt like we was both ready. He was more ready before I was, but it took me awhile to decide about that.

Interviewer: And did you know his HIV status?

Interviewee: No.

Interviewer: Did you know if he had other partners at the time you decided to have unprotected sex?

Interviewee: I knew he had one partner while we were seeing each other.

A 48-year-old HIV-positive woman with three children and both male and female sexual partners also linked her decision to stop using condoms with a man to her perception that in her relationship with her partner the two had become committed to each other.

Interviewee: … In oral sex, as well as sex, I always use a condom, no matter what. Unless later on down the line, we decide to be girlfriend and boyfriend. They want a live-in partner then, so I just don’t use them.

A 30-year-old HIV-negative woman who has children and was pregnant at the time of the interview also described her condom use with past male partners as linked to their commitment to her, including the fact that they had children together.

Interviewer: Okay. So with what partners do you use condoms?

Interviewee: I’m trying to think – and it’s a loaded question. Okay. I’ve used condoms with my current current. I’ve used condoms in the past … I’ve used condoms with the majority of my sexual partners. Okay? I’ve had three guys that I know I’ve never – like I have used the condom, but more than likely we don’t use condoms. Like those are the fathers –

Interviewer: Okay. So you’re less likely [to use condoms with partners who are the fathers of your children] –

Interviewee: Yes, those are the fathers. It’s less [men] that I don’t use condoms with than I do use condoms with … Unfortunately, they’re the fathers of my children.

Several of the participants who did not use condoms with male partners looked back with regret on those choices, based on the perceptions they had of their partnerships being committed and exclusive, which in hindsight had not been the case. One 27-year-old HIV-positive woman with children discussed her perspective on her previous choices regarding condom use:

Interviewee: Myself, let's see, I'm not going to say, because I wasn't having casual sex. I was in a relationship. So back then I would say being stupid. Thinking I could trust him not wanting to wear a condom anymore. He my boyfriend, he okay. And not understanding that okay wasn't okay.

Transactional sex

A history of transactional sex (TS) in this population was common, with 14 of 29 women reporting having exchanged sex for money, drugs, or goods since they were 18. A greater number of HIV-positive women reported TS (10 of 15 HIV-positive women as compared to four of 14 HIV-negative women). Most of the HIV-negative women related a small number of incidents in which they accepted money or goods for a sexual act. However, more of the HIV-positive women related longer periods of time in which they conducted TS, and that the TS was linked to prolonged substance use during which TS was a regular occurrence. Of the eleven HIV-positive women reporting TS, four were WSMW and one was WSW.

Most of the women who related a history of TS linked their TS to drug use, trading sex for drugs or for money to buy drugs. One 28-year-old HIV-negative woman related her story as follows:

Interviewee: So when I first started out sniffing cocaine, it was like a thing – it's the same thing as prostitution, but you just look at it different because of the fact that you're not on the street corner prostituting your body, selling your body. You're selling your body at the club; you know what I'm saying. Or at a bar, you meet somebody and it's kinda like a one-night's thing kind of a thing … For money, you know what I'm saying. They pay you. But it's not like you go there and it's like pay me for sex. It's like you kinda like let them offer you; you know what I'm saying, versus somebody that works the street corners like, "I need my money. " … But all in all it's the same thing. There's really no difference.

A 39-year-old HIV-positive woman with children related her substance abuse as a teenager as a gateway to her TS work beginning at age 17:

Interviewee: With the drug use, me wanting to get high and I had to do it some kind of way, so I just be walking down the street. Somebody see me and it went from there. That's how I went. And I just be walking.

Another participant, a 48-year-old HIV-positive woman with three children, similarly linked her TS work to her drug use but communicated the fact that she stopped “caring” as influencing her decisions regarding condom use during TS.

Interviewee: I moved to [another city] one time and I was on crack real bad. These drug dealers or so-called pimps or whatever, I wanted to get high. I ain’t care how I got high, so I tricked without condoms or I’ll have sex with a couple boyfriends without condoms. Who does that? You don’t know these people for real, now that I got it. You don’t know these people.

A 33-year-old HIV-positive participant related her decision-making surrounding condom use during TS as her inner conflict about exposing others to HIV weighed against her need for money and drugs:

Interviewee: You know, I don’t understand these men. I tell them that I’m HIV positive, and they act like I just said I have a headache. And you still want to have unprotected sex. That scares me, too. But of course, there go that security again, that money, the car to drive, the place to stay, the alcohol, the drugs. Okay.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored the understudied topic of the sexual practices of recently incarcerated women. Many participants described having sex with women as an important component of their committed romantic relationships and their lifetime sexual practices. It is possible that women’s sexual relationships with other women may plan an important role in HIV risk among this vulnerable population, but this role has not been well-studied. The prevalence of women who have had sex with women in our sample (11/29, or 39%) was higher than that reported by the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), in which 11.7% of women aged 15–44 reported sex with another woman in the preceding 12 months, with a slightly higher percentage (12.5%) reporting ever had a sexual experience with another woman.(Chandra, 2011) Eleven of 29 women were interviewed during their first NC incarceration; the other 17 women had been in prison in NC at least one other time (range 1–9 lifetime NC incarcerations) and had a mean of 18.8 prior arrests (range 2–36 prior NC arrests). While prior incarceration may have contributed to the higher prevalence of WSW in our sample, this data also speaks to the complexity of addressing HIV prevention in this population.

The effect of these relationships on frequency and type of sexual encounters with men, either casual, in relationships, or through transactional sex is an important factor to consider when designing appropriate HIV prevention messages and interventions. Among the participants in our study, the four women with primary female sexual partners in the months leading up to incarceration were all HIV-negative, and only one had a history of TS work. In contrast, more of the women with previous male and female partners (but only male partners immediately prior to incarceration) were HIV-positive and reported a history of TS. While this is a qualitative study designed to understand contextual aspects of women’s risk of HIV rather than to draw statistical associations, these findings suggest that a larger study to explore these associations quantitatively may be warranted.

WSW have traditionally been thought of as a group at low risk of STI or HIV risk, with no confirmed cases of WSW-transmitted HIV in the absence of other risk factors (such as intravenous drug abuse or sex with men). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), 2006) However, there are often important differences between sexual practices and sexual identity, and sex with men likely plays a larger role in the lives of WSW than is often assumed.(Everett, 2012) This disconnect is well-documented among men who have sex with men who also have female partners, but in many communities representative of our study cohort the same is likely true of WSW, who may not identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual but have sex with women.(Everett, 2012; Pathela et al., 2006; Saleh, Operario, Smith, Arnold, & Kegeles, 2011) In one study examining HIV risk among self-identified bisexual women in the US, 17% of bisexual women and 0.5% of lesbians reported unprotected vaginal or anal sex with a male partner during the two months prior to the survey.(Norman, Perry, Stevenson, Kelly, & Roffman, 1996) Another study of AA WSW and WSMW in the Southern US found high rates of STIs in both groups, in particular WSMW.(Muzny, Sunesara, Martin, & Mena, 2011) Other studies have demonstrated similarly high rates of risky sexual practices, poor access to health care, substance abuse, mental illness, and history of childhood sexual abuse among WSW and WSWM.(Bauer & Welles, 2001; Reisner et al., 2010; Roberts, Austin, Corliss, Vandermorris, & Koenen, 2010; Sweet & Welles, 2012) WSW and WSMW who have been incarcerated may have risk factors for high-risk sexual partnerships elevated beyond those of other previously incarcerated women such as substance abuse or unstable housing. For instance, in a study of female detainees in Baltimore in which 33% identified as lesbian or bisexual, identification as lesbian was negatively associated with having housing on release.(McLean, Robarge, & Sherman, 2006)

The diversity of sexual practices and life experience among the women we studied was profound, underscoring the complexity of designing appropriate HIV prevention models for women who may not see themselves as being at-risk. Addressing condom use and partner concurrency among at-risk women is a key factor in reducing HIV acquisition and preventing forward transmission following release. Under-recognized or poorly understood sexual practices of WSW could lead to use of language or descriptions that alienate the intended audience, mitigating HIV prevention and safer sex promotion efforts.

While women who have sex exclusively with women may be somewhat sheltered from HIV risk, all of the women in our sample with primary female partners had, at some point in their lives, had sex with a male partner, and some of their female partners had concurrent male sexual partners. Given this, as well as the STI risk documented in prior studies, these women continue to be at risk for HIV, albeit perhaps less so than women with more male sexual partners. Of real concern in this study population were the women who represent the heterogeneity of sexual practice, occupying the gray areas of sexuality and societal convention. Women who have sex only occasionally with male partners, particularly in a situation involving TS or other coercive circumstances, may not disclose these practices or see themselves as at risk for HIV.

This study may be limited in its generalizability, as qualitative studies are not designed to detect statistically significant differences, in this case between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups. While the qualitative interviews allowed exploration of HIV risk factors on multiple levels, the onetime interview depended on participant comfort with in-depth questions and rapport with the interviewer. Partnerships with men and women may be under-reported as interviewers only specifically asked about the past six months prior to incarceration. Most participants volunteered information about partners prior to that time, especially in the case of participants with recent male partners as well as previous female partners. Finally, the observed age difference between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups may be noteworthy if older women were more forthcoming with their experiences (or had simply had a longer period of lifetime sexual activity). We did not observe patterned differences in the length and detail level of the interviews that would suggest this possibility and the two groups appeared balanced in terms of willingness to answer questions and recall relevant details.

Addressing practices that place women at risk for HIV rather than focusing on sexual identity in a population that does not, as a whole, connect to these terms (e.g. lesbian, bisexual) is an important future step in intervention design. The chaotic and complex sexual relationships described by this study’s participants are punctuated by incarcerations and periods of drug use, along with their economic and emotional consequences. This upheaval and unpredictability requires more flexibility in the definitions and requirements of relationships and, often, acceptance of risky practices and concurrency. The prison setting offers an opportunity for structured intervention targeting HIV prevention in this vulnerable population. Recognition of the complex sexuality of incarcerated women and its influence on their risk for HIV and STI acquisition is essential in ensuring the efficacy of these efforts.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

Although women may not formally identify as bisexual or lesbian, sex with women was an important component of this cohort’s sexuality. Addressing condom use, heterogeneity of sexual practices, and partner concurrency among at-risk women, particularly in the context of substance abuse, should be considered as part of HIV prevention efforts, particularly in populations with a history of incarceration. Fertility desire and partner choice are additional variables that may increase these women’s risk of HIV if they have the opportunity to negotiate sexual encounters, suggesting a role for media campaigns specifically addressing these concerns. Opportunities for HIV prevention and partner testing are numerous as these women interact with the health care system (e.g. for STI testing and treatment or for pregnancy-related care) or the criminal justice system (the women in this study had a mean of 18.8 prior arrests). Finally, the critical role of routine opt-out HIV testing in high-risk populations, e.g. those with prior contact with the criminal justice system, is underscored by this research.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: The project described was supported by a National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Health (F32 DA030268-01). Additional support was provided by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410) and the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR000083. Dr. Farel had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Biographies

Claire Farel, MD, MPH is an Assistant Professor in the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases at the University of North Carolina (UNC). Her research interests include HIV prevention and care in vulnerable populations, particularly women, and determinants of HIV/STI risk among incarcerated women.

Sharon D. Parker, PhD, MSW, MS is an NIH Postdoctoral Fellow at Brown University/Miriam Hospital Division of Infectious Diseases. She examines social and behavioral factors influencing health disparities, especially in corrections, and HIV prevention and interventions among southern African Americans.

Kathryn E. Muessig, PhD is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Behavior at UNC and in the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases. Her research, based in the US and China, focuses on improving provision of mental and physical health services related to HIV/STI in vulnerable populations.

Catherine A. Grodensky, MPH is the UNC Center for AIDS Research Social/Behavioral Science Core Manager. She has expertise in HIV prevention and antiretroviral adherence as well as survey development, qualitative research, and the relationship between alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence.

Chaunetta Jones, MA is a second year MPH student in the Department of Health Behavior at UNC and concurrently a PhD candidate in Medical Anthropology researching economic inequalities and structural barriers shaping responses to antiretrovirals among people living with HIV.

Carol E. Golin, MD, an Associate Professor in the Department of Health Behavior at UNC and the School of Medicine, focuses on behavioral interventions to enhance compliance and care for persons living with HIV and access to care for incarcerated persons.

Catherine I. Fogel, PhD RNC FAAN, a Professor in the UNC School of Nursing, studies health disparities and health promotion of vulnerable and incarcerated women. She focuses on the prevention of STI/HIV in women and the lives of women with HIV.

David A. Wohl, MD is an Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases and Co-Director of the AIDS Clinical Trials Unit at the UNC. His major research interests are the nexus between HIV and incarceration and metabolic complications associated with HIV infection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

To the best of our knowledge, no significant conflict of interest, financial or other, exists.

Contributor Information

Claire E. Farel, University of North Carolina, School of Medicine, UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, 130 Mason Farm Road, CB# 7030, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, T: 919-966-2536, F: 919-966-6714, cfarel@med.unc.edu.

Sharon D. Parker, Brown University School of Medicine and The Miriam Hospital, Division of Infectious Diseases, 164 Summit Ave, Providence RI 02906, T: 401-793-4766, F: 917-720-9002, parkersdr@gmail.com.

Kathryn E. Muessig, UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, UNC- Chapel Hill, Department of Health Behavior Gillings School of Global Public Health, CB# 7440, Chapel Hill NC 27599, Kate_muessig@med.unc.edu.

Catherine A. Grodensky, Manager, UNC Center for AIDS Research Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Core, UNC Center for AIDS Research, 135 Dauer Dr., Chapel Hill, NC 27599, T: 919-843-2532, F: 919-966-2921, grodensk@med.unc.edu.

Chaunetta Jones, UNC- Chapel Hill, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, CB# 7440, Chapel Hill NC 27599, T: 919-843-2532, F: 919-966-2921, chajones@live.unc.edu.

Carol E. Golin, UNC- Chapel Hill, Gillings School of Global Public, Health and School of Medicine, Department of Health Behavior, Department of Medicine, 302 Rosenau Hall, CB #7440, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, T: 919-843-2532, F: 919-966-2921, carol_golin@med.unc.edu.

Catherine I. Fogel, UNC- Chapel Hill, School of Nursing, 4012 Carrington Hall CB #7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, T: 919-966-3590, F: 919-966-3647, cfogel@email.unc.edu.

David A. Wohl, UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, Co-Director, HIV Services for the NC Department of Correction, 130 Mason Farm Road, CB#7215, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, P: (919) 843-2723, F: (919) 966-8928, wohl@med.unc.edu.

References

- Bauer GR, Welles SL. Beyond assumptions of negligible risk: sexually transmitted diseases and women who have sex with women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1282–1286. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1282. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) HIV/AIDS among women who have sex with women. CDC HIV/AIDS fact sheet. 2006 (pp. 2 p. digital, PDF file.). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/resources/factsheets/pdf/wsw.pdf.

- Chandra Anjani. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States : data from the 2006–2008 national survey of family growth. Hyattsville, Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Sexually Transmitted Infections: Examining the Intersection Between Sexual Identity and Sexual Behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9902-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld LA, Snell TL. Women offenders (Bureau of Justice Special Report NCJ 175688) Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow CW. Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Washington, DC: U.S.Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. United States Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Women and HIV/AIDS in the United States. 2012 http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/6092-10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KM, Jacobs N. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors among female jail detainees: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):818–825. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.818. [Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean RL, Robarge J, Sherman SG. Release from jail: moment of crisis or window of opportunity for female detainees? J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):382–393. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [Review]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ, Karberg JC United States Bureau of Justice Statistics. Drug use and dependence, state and federal prisoners, 2004. Washington, DC: U.S.Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muzny CA, Sunesara IR, Martin DH, Mena LA. Sexually transmitted infections and risk behaviors among African American women who have sex with women: does sex with men make a difference? Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(12):1118–1125. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AD, Perry MJ, Stevenson LY, Kelly JA, Roffman RA. Lesbian and bisexual women in small cities--at risk for HIV? HIV Prevention Community Collaborative. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(4):347–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed October 4, 2012];N.C. Epidemiologic Profile for HIV/STD Prevention and Care Planning (12/11) 2011 http://epi.publichealth.nc.gov/cd/stds/figures/std11rpt.pdf.

- North Carolina Department of Public Safety. Automated System Query Custom Offender Reports. Prison Population 3-31-2012. 2012 http://webapps6.doc.state.nc.us/apps/asqExt/ASQ. [Google Scholar]

- Pathela P, Hajat A, Schillinger J, Blank S, Sell R, Mostashari F. Discordance between sexual behavior and self-reported sexual identity: a population-based survey of New York City men. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):416–425. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, Hall HI. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Case P, Grasso C, O'Brien CT, Harigopal P, Mayer KH. Sexually transmitted disease (STD) diagnoses and mental health disparities among women who have sex with women screened at an urban community health center, Boston, MA, 2007. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(1):5–12. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b41314. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, Koenen KC. Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2433–2441. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA, White BL, Stewart PW, Golin CE. Characteristics and behaviors associated with HIV infection among inmates in the North Carolina prison system. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1123–1130. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh LD, Operario D, Smith CD, Arnold E, Kegeles S. "We're going to have to cut loose some of our personal beliefs": barriers and opportunities in providing HIV prevention to African American men who have sex with men and women. Aids Education and Prevention. 2011;23(6):521–532. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.6.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Frisman L, Lin HJ, Leukefeld C, Oser C, Havens JR, Clarke J. Relationship Influence and Health Risk Behavior Among Re-Entering Women Offenders. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(3):230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C, Palmer J, Oser C, Kaplan A, Krietemeyer J, Surratt HL. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. Prison Journal. 2007;87(1):143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Royse D, Leukfeld C. Substance use criminality, and social support: an exploratory analysis with incarcerated women. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(2):237–243. doi: 10.1080/00952990601174865. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet T, Welles SL. Associations of Sexual Identity or Same-Sex Behaviors With History of Childhood Sexual Abuse and HIV/STI Risk in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(4):400–408. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182400e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]