Abstract

Plerixafor (Mozobil®) is a CXCR4 antagonist that rapidly mobilizes CD34+ cells into circulation. Recently, plerixafor has been used as a single agent to mobilize peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Although G-CSF mobilization is known to alter the phenotype and cytokine polarization of transplanted T-cells, the effects of plerixafor mobilization on T-cells have not been well characterized. In this study, we show that alterations in the T-cell phenotype and cytokine gene expression profiles characteristic of G-CSF mobilization do not occur following mobilization with plerixafor. Compared to non-mobilized T-cells, plerixafor-mobilized T-cells had similar phenotype, mixed lymphocyte reactivity, FoxP3 gene expression levels in CD4+ T-cells, and did not undergo a change in expression levels of 84 genes associated with Th1/Th2/Th3 pathways. In contrast to plerixafor, G-CSF mobilization decreased CD62L expression on both CD4 and CD8+ T-cells and altered expression levels of 16 cytokine-associated genes in CD3+ T-cells. To assess the clinical relevance of these findings, we explored a murine model of GVHD in which transplant recipients received plerixafor or G-CSF mobilized allograft from MHC-matched, minor histocompatibility mismatched donors; recipients of plerixafor mobilized PBSC had a significantly higher incidence of skin GVHD compared to mice receiving G-CSF mobilized transplants (100% vs. 50% respectively, p=0.02). These preclinical data show plerixafor, in contrast to G-CSF, does not alter the phenotype and cytokine polarization of T-cells, which raises the possibility that T-cell mediated immune sequelae of allogeneic transplantation in humans may differ when donor allografts are mobilized with plerixafor compared to G-CSF.

Keywords: Stem Cells, Th1/Th2 Cells, Transplantation

INTRODUCTION

For adults with malignancies, mobilized peripheral-blood progenitor cells (PBPC) are the preferred source of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) for autologous transplants and matched sibling allogeneic transplants because PBPC’s engraft faster than bone marrow-derived progenitor cells and are technically easier to collect (1). The administration of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) results in successful mobilization of PBPC’s in most healthy donors. While most regimens using G-CSF succeed in collecting adequate numbers of PBSC from healthy donors, 5–10% of patients will mobilize poorly, necessitating multiple large volume apheresis or bone marrow harvesting (2). Although G-CSF is generally well tolerated in healthy donors, it frequently causes bone pain, headache, myalgia and in rare circumstances life threatening side effects such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and splenic rupture (3). The number of lymphocytes contained in G-CSF mobilized PBPC grafts is about 10–15 times higher than BM grafts (4–5). Despite containing substantially higher numbers of T cells, several prospective, randomized trials have shown that the incidence of acute GVHD is not higher in recipients of G-CSF mobilized PBPC allografts compared to BM allografts (4, 6–10). Although a number of mechanisms have been postulated to account for this phenomenon, alterations in cytokine-related genes in T-cells mobilized with G-CSF including a polarization towards a type-2 cytokine (Th2) response is thought to play a pivotal role in reducing the ability of T cells to trigger acute GVHD (11–14). The distinct cytokine production profile of Th2 cells has also been shown in animal models to contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic GVHD, which has been shown in randomized trials to occur more commonly with G-CSF mobilized transplants compared to bone marrow transplants.

Plerixafor (Mozobil®) is a bicyclam compound that inhibits the interaction of stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1) to its cognate receptor CXCR4 (15–16). CXCR4 is present on CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and its interaction with SDF-1 plays a pivotal role in the homing of CD34+ cells in the bone marrow (17–18). Inhibition of CXCR4-SDF-1 binding by plerixafor releases CD34+ cells into the circulation, allowing them to be collected easily by apheresis (19). The addition of plerixafor to G-CSF has a potent synergistic effect on the mobilization PBPC in patients undergoing autologous transplantation. Plerixafor is approved in the United States in combination with G-CSF for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and collection for subsequent autologous transplantation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma patients.

Plerixafor given as a single agent can also mobilize substantial numbers of hematopoietic progenitor cells into the circulation. A phase one, dose escalating study in healthy donors demonstrated that large numbers of CD34+ cells were rapidly mobilized in healthy donors following a single subcutaneous injection of plerixafor with the peak CD34+ mobilizing effects occurring 6–9 hours after a 240 µg/kg of plerixafor in the absence of any dose limiting toxicities (20). Importantly, side effects were mild and transient, and did not include bone pain, fever and myalgias commonly observed following G-CSF administration. Based on these data, investigators have recently begun to explore the use of single agent plerixafor to mobilize PBPC for allogeneic transplantation, although it use in this setting remains investigational. The first published study to use plerixafor alone to mobilize PBPC for allogeneic transplantation showed successful mobilization of CD34+ cells in healthy stem cell donors and sustained tri-lineage hematopoietic reconstitution in 14 transplant recipients of plerixafor mobilized allografts (21–22). Leukapheresis products mobilized with plerixafor contained a higher number of CD3+ T cells compared to G-CSF, and in a limited analysis performed on 4 donors did not appear to alter the phenotype of mobilized T cells. Because of its potential use as a single mobilization agent in this setting, we performed a detailed analysis of the phenotype, cytokine gene expression profiles, and immunological properties of T cells mobilized with plerixafor in healthy donors. Furthermore, we used an MHC-matched mouse model of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation to assess whether the phenotypic and genotypic differences observed in T cells mobilized with plerixafor compared G-CSF would impact transplant outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

To analyze G-CSF mobilized cells, 11 healthy subjects had PBMCs collected at baseline then were mobilized with 5 daily doses of subcutaneous G-CSF (10 µg/kg/daily, NHLBI protocols 04-H-0078, 99-H-0050 and 99-H-0064). Two hours following the 5th dose of G-CSF, subjects had peripheral blood mononuclear cell collected from the blood followed by a 15–25 liter apheresis procedure to collect mobilized cells. To analyze plerixafor-mobilized cells, 20 healthy subjects underwent plerixafor mobilization on NHLBI protocols 04-H-0078 and 06-H-0179. PBMCs collected at baseline then 6 hours following a single subcutaneous injection of plerixafor at a dose of 240 µg/kg (n=12). Eight of these subjects also underwent a 15–25 liter apheresis beginning 6 hours following plerixafor administration. Freshly collected apheresis products were analyzed by flow cytometry for cellular content. Cells were frozen in 10% DMSO for subsequent phenotypic, genotypic and in vitro and in vivo functional studies. Leukapheresis procedures were performed using the model CS-3000 Plus (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) continuous-flow cell separator. Complete blood counts were assayed using an electronic counter and CD34, CD3 and other cell counts were enumerated by flow cytometry, immediately before and after apheresis, as previously described (23)

Phenotypic analysis of cells

Six-color flow cytometry was used to analyze mononuclear cells obtained from apheresis products or from peripheral blood following mobilization as well as from pre-mobilization blood and blood obtained immediately before initiating apheresis. Peripheral blood was drawn by venipuncture into tubes containing heparin and stained within 8 hours of collection. A 100-µL aliquot of whole blood was incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with antibodies. Each experiment was performed using the appropriate isotype controls. Following incubation, erythrocytes in these samples were lysed (Whole Blood Lysing Reagent; Coulter, Fullerton, CA), washed twice, and then fixed with paraformaldehyde. All samples were analyzed by using a CYAN MLE cytometer (Dako-Cytomation, Ft. Collins, CO). Summit software (Dako-Cytomation) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Mixtures of six fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies were used in the same tube to assess the phenotype in different cell populations. CD3-PE-Cy7, CD4-APC-Cy7, CD8-PerCP, CD16-APC-Cy7, CD56-PE-Cy5, CD19-APC and CD34-FITC were used to gate T cell, B cell, NK cell and hematopoietic progenitor cell populations. CD57-FITC, CD27-FITC, CD62L-FITC, HLA-DR-FITC, CD45RA-FITC, pan-TCRgd-FITC, CD38-FITC, CD69-FITC, CXCR4-PE, CD25-PE, CCR7-PE, CD71-PE, CD45RO-PE and pan-TCRab-PE were used to assess the phenotype of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. All the monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) except for pan-TCRgd-FITC and pan-TCRab-PE (Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Assessment of Th1, Th2, and Th3 cytokine gene expression levels in donors mobilized with plerixafor vs. G-CSF

Gene expression analysis was performed on CD3+ and CD4+ T cells obtained from the blood or apheresis collections of healthy subjects at baseline and after mobilization with 240 µg/kg of plerixafor or G-CSF alone (10 µg/kg/day × 5 days). Fresh samples were ficolled (LSM®;MP Biomedicals) and CD3+ cells were isolated on fresh and thawed samples following manufacturers’ instructions using Human PanT Cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi). CD4+ T cell fractions were positively selected following manufacturers’ instructions using CD4 MicroBeads (Miltenyi). Cryopreserved specimens were thawed in a 37° water bath, washed with 1X RPMI and 10% heat inactivated FBS, then were treated with DNase (Roche) for 30 minutes at 37° with the CD3+ and CD4+ T cell fractions being isolated using the same procedure outlined above.

RNA was isolated from CD3+ and CD4+ T cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated CD3+ RNA was sent to SuperArray Bioscience Corporation where it was reverse transcribed and analyzed in quantitative real time PCR reactions using the Syber Green RT2Profiler™ PCR Array Human Th1-Th2-Th3 plates. Baseline and post plerixafor or post G-CSF samples were compared for each healthy subject.

For assessment of Foxp3 gene expression levels from mobilized donors RNA (1µg) was obtained from purified CD4+ T cells. RNA was DNase treated prior to reverse-transcription using SuperScriptIII Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). 5 µl of cDNA was added to a final volume of 25 µl containing 1x Quantitech Multiplex PCR Kit (QIAGEN), 0.4 uM of each forward and reverse primers for actin and Foxp3, and 0.2 uM of each probe. Actin and Foxp3 primer and probe sequences were previously published (24–25). All samples were run in triplicates on a Peltier Thermal Cycler PTC-200 (MJ Research) with a Chromo4 Continuous Fluorescence Detector 4. Thermal cycling conditions consisted of 95° for 10 minutes followed by 94° for 1 minute and 60° for 1 minute (45 cycles). The expression of Foxp3 was normalized to the actin levels within each individual sample and the fold change from baseline calculated for each healthy subject.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

The alloreactivity of mobilized cells collected at baseline and following plerixafor mobilization were tested in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) by 3H-thymidine uptake and CFSE dilution assays. Pooled and irradiated PBMCs from three normal volunteers were used as stimulators. For the thymidine uptake MLR, 5 ×105 responder MNCs in 100 µl culture media were co-incubated with equal numbers of irradiated (50Gy) stimulator cells in 96-well round-bottom plates. The culture media consisted of RPMI (GIBCO Life Technologies) supplemented with 5% human AB serum, L-glutamine, gentamicin and Hepes buffer. After 5 days, the wells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at 1 µCi/well. After an additional 18-hour incubation, the cells were harvested and thymidine incorporation into DNA was quantified using a beta counter (Beckman Coulter). The results are reported as counts per minute. For the CFSE dilution assay MLR, responder cells were incubated in in pre-warmed working concentrations of CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in DPBS (0.6µM) for 15 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then washed and resuspended in fresh, serum free RPMI then were incubated with equal numbers of irradiated (50Gy) stimulator cells for 5 days and thereafter harvested and stained with propidium iodide, CD3-PerCP and CD25-APC monoclonal antibodies (BD Farmingen). Four-color flow cytometry was performed on a FACS Calibur dual-laser cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The precursor frequency of alloreactive T cells was estimated using FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

MHC-matched murine transplantation model

Animals

Eight to 12 week old BALB/c, (H-2d, Ly9.1+, 7/4−), B10.d2 (H-2d, Ly9.1−, 7/4+) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in microisolator cages at NHLBI pathogen-free facilities. Transplanted animals were provided acidified water containing neomycin. All experiments were approved by the NHLBI animal care and use committee (protocol no. HB-0112).

Mobilization

To mobilize PBSC, B10.d2 donor mice received either G-CSF (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) given as subcutaneous (s.c) injections daily × 5 days (10µg/mouse/day) or plerixafor (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA) given as a single s.c. injection (100µg/mouse). Mobilized PBSC were collected from spleens harvested 6 hours after the last injection for both groups. Spleens were also harvested from B10.d2 donor mice that received saline (HBSS) injections as controls.

Flow cytometry

The phenotype of mobilized cells obtained from spleens (6 hours after last injection) was evaluated following staining with fluorochrome conjugated anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, DX5, Gr1, sca-1, c-Kit, CD25, CD62L (BD Pharmingen). Intracellular staining of FoxP3 was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience, CA, USA). Regulatory T cells (Treg) were determined by positive staining for CD4 and FoxP3. To measure lymphoid and myeloid chimerism peripheral blood collected after transplantation was stained with Ly9.1-FITC, CD3-PerCP and CD19-APC (BD Pharmingen) and 7/4-PE (Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada). For all flow cytometric staining assays, cells were incubated with rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (BD Pharmingen) for 10 minutes at room temperature prior to incubation with specific antibodies. Cells were acquired on FacsCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using Summit Software v3.3 (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) or FCS express software (DeNovo, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada).

Proliferation and suppression assays

CD4+ T cells were selected using Miltenyi immunomagnetic beads from the spleens of mobilized animals and then co-cultured (50,000/well) with MHC mismatched irradiated (50Gy) concanavalin A (Con A) blasts (range 8,000–500,000 cells) from C57BL/6 mice in 96-well plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2-ME (Invitrogen, Gibco, CA, USA). After a 72–96 hour co-culture, cells were pulsed with 1µCi/well of 3H-thymidine for 16 hours then were harvested onto solid filters and measured in a microbeta scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA). Con A activated T cell blasts were prepared by culturing C57BL/6 splenocytes at 5 × 106 cells/ml in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2-ME, and 5 µg/ml Con A (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 48–96 hours.

Transplantation

After mobilization, a single suspension of donor cells was prepared by homogenizing the spleen and filtering through a 70µm nylon mesh filter. Red cells were ACK lysed for 5 minutes at room temperature (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). BALB/c recipient mice were conditioned with 950cGy total body irradiation (Shepherd Mark I 68A Cs 137, JL Shepherd and Associates, San Fernando, CA), then 3–6 hours later were injected with 15×106 mobilized splenocytes intravenously via tail vein injection. This GVHD model has been shown to be dependent on transferred CD4 positive T cells. Therefore, some experiments were performed with an identical number of CD4 positive T cells. In such experiments, recipients were injected with 2×106 CD4 positive and 13×106 CD4 negative splenocytes intravenously via tail vein injection.

Onset of GVHD symptoms including alopecia, hunched posture, loss of activity and weight loss was assessed twice weekly and was graded using a previously described GVHD scoring system (26). Briefly, a total of 9 points represents the highest score: alopecia 0–4; weight loss 0–2 (<5%=0; 5–15%=1; >15%=2); posture 0–2; ear or eye irritation 0–1. All mice were kept alive for up to 100 days and no mice died due to GVHD.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups (baseline vs. plerixafor) were tested (when applicable) by paired samples t-test using SPSS 10 statistical software (SPSS Inc.). Analysis of the real-time PCR arrays utilized a two-sample paired t-test to identify genes that were up or down regulated after treatment. The corresponding p-values were evaluated based on the permutation technique. Since the number of distinct permutations is limited when the sample size is small, the null statistics of non-significant genes was pooled to generate the permutation-based null distribution (27) The false discovery rate (FDR) was estimated using the q-value function (28) given in R language. A student’s T-test , Fisher’s exact test, or log-rank test were used to assess the differences between mouse transplant groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Mobilization with Plerixafor in healthy subjects

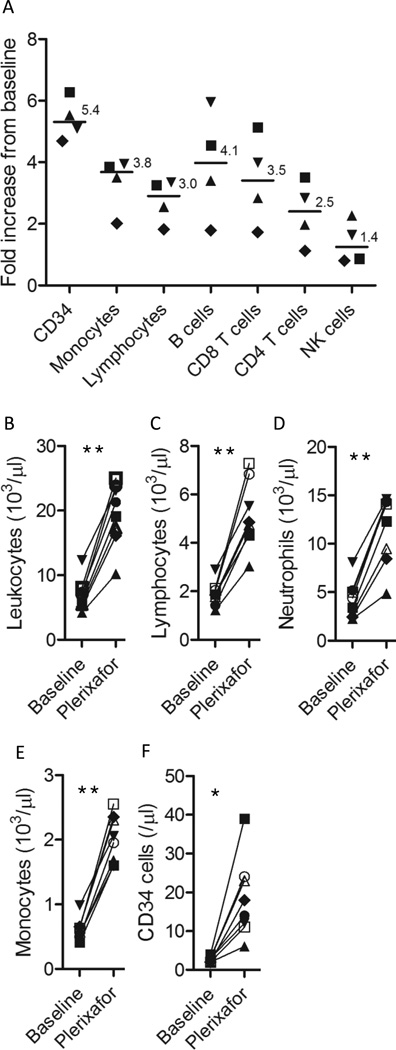

Apheresis products were collected from 8 healthy subjects mobilized with a single 240 µg/kg injection of plerixafor. Relative to the weight of the subjects mobilized, apheresis collections following plerixafor mobilization (median 19.6 liters apheresed; range 15–22 liters) contained a median 81 ×106 CD19+ B cells/kg, a median 274 ×106 CD3+ T cells/kg, and a median 1.6 ×106 CD34+ cells/kg (Table I). Plerixafor preferentially mobilized CD34+ cells followed by monocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 1A). Within the lymphocyte compartment, B cells were preferentially mobilized followed by T-cells and NK cells. Among CD19+ B cells, CD20, kappa, and lambda expression did not change from baseline, although the percentage of B cells expressing CD27 declined significantly in 7/8 donors consistent with plerixafor preferentially mobilizing naïve type B cells; the median percentage of CD27+CD19+ B cells was 35.1% at baseline and 19% following plerixafor mobilization (p=0.011). The total WBC count, and the absolute numbers of blood neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and CD34+ cells increased significantly from baseline following plerixafor administration (Figure 1B–F). A detailed phenotypic analysis using 6 color flow cytometry of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte subsets at baseline and 6 hours following a single injection of plerixafor or two hours following the 5th dose of G-CSF is shown in Table II. No significant change from baseline was observed following mobilization with plerixafor in the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing the majority of surface markers analyzed including CD45RA, CD45RO, CD34, CD56, CD57, CD27, CD71, and CD62L. Although the phenotype also did not change following G-CSF mobilization in most CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations, there was a significant decline in the percentage of CD4 and CD8 T cells that expressed CD62L and in CD8 T cells that expressed CD27 (Table II).

Table I.

Cellular content of plerixafor mobilized apheresis products

| Age | Sex | Weight (kg) |

Apheresis volume (Liters) |

Total T cells /kg (106) |

Total B cells /kg (106) |

Total CD34+ cells /kg (106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | M | 85 | 20 | 254 | 42 | 1.78 |

| 35 | M | 75 | 15 | 293 | 42 | 4.25 |

| 49 | F | 64 | 18.6 | 263 | 41 | 0.92 |

| 45 | M | 85 | 20 | 332 | 115 | 0.86 |

| 56 | F | 71 | 22 | 285 | 100 | 1.61 |

| 18 | F | 58 | 22 | 512 | 172 | 5.4 |

| 32 | M | 68 | 19 | 53 | 118 | 1.42 |

| 35 | M | 130 | 20 | 133 | 62 | 1.58 |

| Mean | 19.6 | 265 | 87 | 2.2 | ||

Figure 1. Mobilization of blood mononuclear cells after a single dose of plerixafor in healthy subjects.

Blood samples were collected prior to the start of mobilization and 6 hours after a single injection of 240 µg/kg of plerixafor immediately before apheresis. Each symbol represents an individual subjects. **p<0.001; *p<0.01.

Table II.

Effect of plerixafor or G-CSF mobilization on circulating T-cell subsets*

| CD3+CD4+ T-cells |

Baseline | After Plerixafor |

p-value** | Baseline | After G-CSF |

p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45RA+ | 45.0±8.2 | 50.8±12.4 | 0.1 | 41.8±10.5 | 31.0±4.5 | 0.06 |

| CD45RO+ | 49.4±9.3 | 45.3±10.3 | 0.06 | 57.0±14.3 | 58.4±5.8 | 0.26 |

| CD57+ | 3.3±3.3 | 2.4±1.9 | 0.28 | 5.7±4.8 | 6.5±9.8 | 0.50 |

| CD27+ | 87.7±6.8 | 81.6±17.6 | 0.42 | 70.5±25.9 | 57.3±31.4 | 0.20 |

| CD25+ | 16.2±11.1 | 11.7±10.0 | 0.1 | 23.9±19.1 | 10.6±7.1 | 0.20 |

| CD62L+ | 34.1±32.4 | 27.4±32.7 | 0.1 | 67.8±15.2 | 29.5±22.9 | 0.03 |

| CD71+ | 1.4±0.9 | 1.8±1.5 | 0.55 | 0.6±0.4 | 1.2±0.8 | 0.31 |

| HLA-DR+ | 5.3±1.6 | 3.8±1.2 | 0.1 | 5.8±1.9 | 4.4±2.1 | 0.40 |

| CD3+CD8+ T-cells |

Baseline | After Plerixafor |

p-value** | Baseline | After G-CSF |

p-value** |

| CD45RA+ | 58.2±24.5 | 65.5±23.9 | 0.11 | 55.2±12.2 | 51.4±3.2 | 0.79 |

| CD45RO+ | 43.0±21.0 | 34.9±17.8 | 0.09 | 49.3±13.3 | 46.6±4.4 | 0.13 |

| CD57+ | 7.0±3.3 | 5.0±1.77 | 0.09 | 22.0±17.4 | 21.9±14.0 | 0.41 |

| CD27+ | 86.4±10.4 | 83.8±22.2 | 0.71 | 65.0±9.7 | 50.2±13.0 | 0.03 |

| CD25+ | 4.0±3.2 | 1.3±1.1 | 0.12 | 5.5±6.5 | 4.6±3.7 | 0.58 |

| CD62L+ | 32.0±33.7 | 29.6±37.1 | 0.39 | 47.1±14.1 | 16.4±12.4 | 0.01 |

| CD71+ | 0.7±0.4 | 0.7±0.36 | 0.88 | 0.5±0.3 | 0.8±0.9 | 0.65 |

| HLA-DR+ | 8.2±3.3 | 4.9±2.1 | 0.08 | 14.9±11.3 | 8.6±6.3 | 0.27 |

Values are reported as percent of total CD4+ or CD8+ T cells.

Comparison of baseline and post plerixafor or G-CSF on T-cell subsets. P-values were calculated as paired T-test.

Impact of plerixafor on cytokine gene expression profiles in T cells

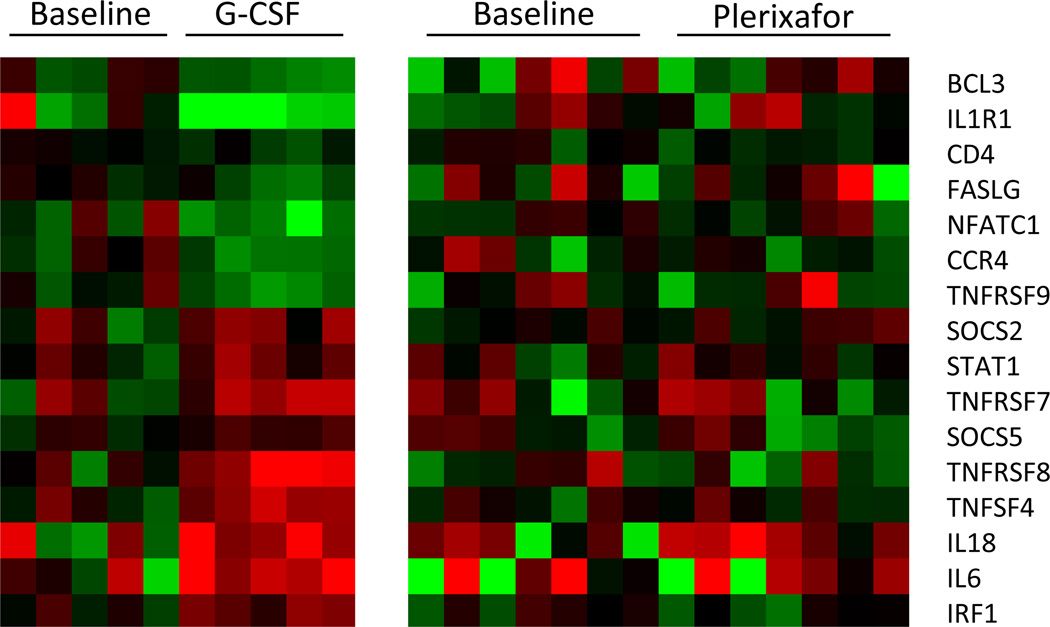

To examine whether plerixafor mobilization altered the cytokine polarization of T-cells, we analyzed cytokine gene expression profiles using a Th1-Th2-Th3 RT-PCR plate in CD3+ T cells collected form subjects mobilized with a single injection of plerixafor vs. CD3+ cells collected from subjects mobilized with 5 daily doses of G-CSF alone. None of the 84 cytokine genes examined were significantly altered from baseline in CD3+ cells mobilized with plerixafor. In contrast, 16/84 (19%) cytokine related genes were significantly altered from baseline in CD3+ T cells following G-CSF mobilization (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Th1 and Th2 gene expression profiles in CD3+ T cells assessed by real-time PCR.

(A) Heat map showing real-time PCR expression levels of 16 genes in CD3+ T cells that changed significantly from baseline following G-CSF mobilization in 5 healthy subjects. All samples were normalized to the center of the mean of the pre G-CSF samples with red denoting up-regulated expression and green denoting down-regulated expression (10% false discovery rate). (B) Gene expression levels of plerixafor did not change from baseline in the 84 measured Th1-Th2-Th3 genes, including the 16 genes that were altered with G-CSF treatment which are displayed.

Impact of plerixafor on T cell alloreactivity

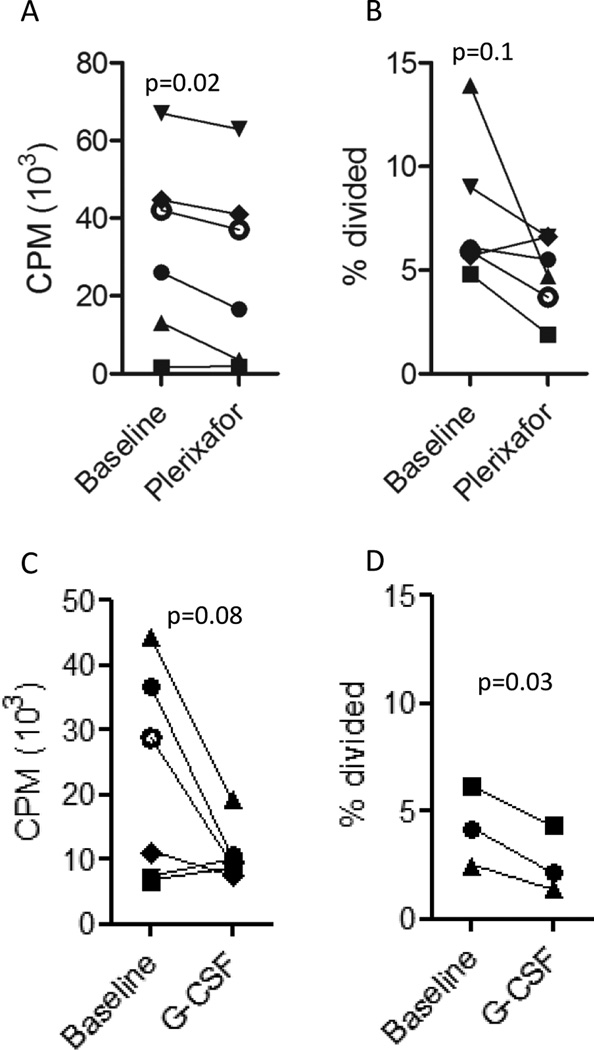

The impact of plerixafor mobilization on T cell alloreactivity was assessed by 2 different MLR methods. Compared to baseline, plerixafor mobilized mononuclear cells had slightly decreased alloreactivity against 3rd party cells using a standard 5 day 3H MLR (Figure 3A). Alloreactivity assessed using a CFSE MLR proliferation assay gated on CD3+ T cells showed plerixafor mobilized T cells had a statistically non-significant decrease in precursor frequency against 3rd party allogeneic stimulators as compared to T cells at baseline (Figure 3B). A similar decline in alloreactivity against 3rd party allogeneic cells was observed in mononuclear cells following G-CSF mobilization as assessed by the 5-day 3H MLR assay (Figure 3C) or CFSE (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. The impact of mobilization on alloreactivity.

The alloreactivity of PBMCs before and after mobilization with plerixafor (A and B) or G-CSF (C and D) against 3rd party PBMC stimulators was measured using a 3H Thymidine uptake (A and C), or CFSE dilution assay gated on viable CD3+ T cells (B and D).

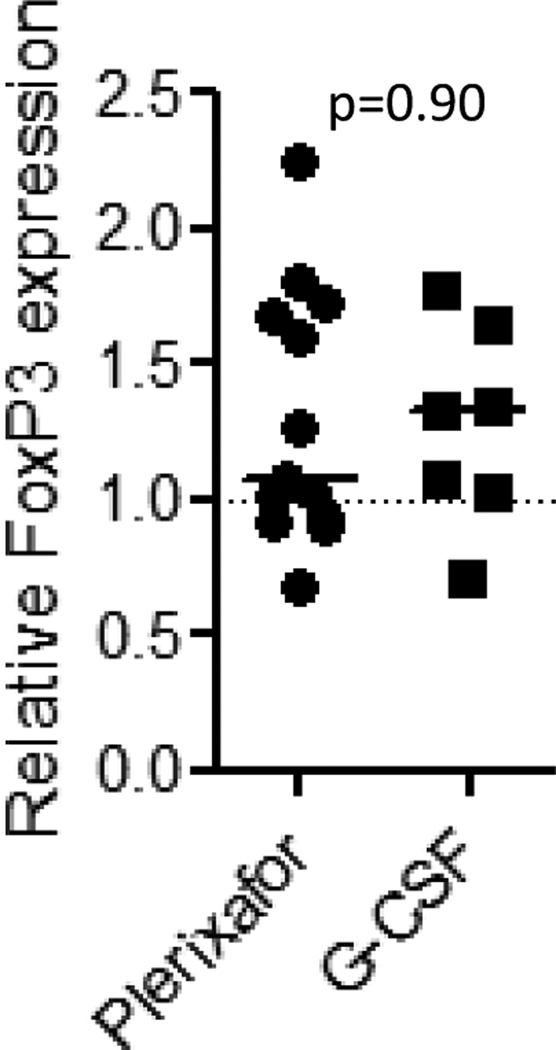

Impact of plerixafor on FoxP3 gene expression in CD4+T- cells

In murine transplant studies Tregs transplanted with allogeneic PBPCs appear to reduce the risk of GVHD. In humans undergoing allogeneic transplantation, an inverse correlation between GVHD and Foxp3 mRNA expression has been reported (29). Therefore, we analyzed FOXP3 expression by RT-PCR in CD4 cells isolated from healthy subjects following mobilization with plerixafor vs. G-CSF. Compared to baseline, no statistically significant changes in FoxP3 gene expression were observed in CD4+ T cells mobilized with either plerixafor or G-CSF (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The impact of mobilization on CD4+ FoxP3 expression.

FoxP3 expression following mobilization compared to baseline in CD4+ cells mobilized with plerixafor or G-CSF showed no fold-change in expression from baseline in healthy subjects mobilized with either plerixafor or G-CSF alone. Line represent the median change from baseline in 13 samples obtained after plerixafor mobilization and 7 samples obtained after G-CSF mobilization.

Mobilization of murine lymphocyte subsets following plerixafor vs. G-CSF administration

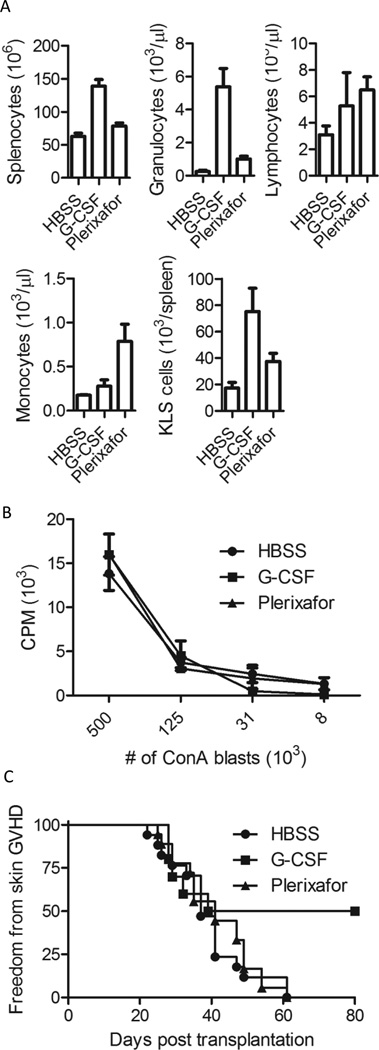

Mobilized PBSC were collected from spleens of mice harvested 6 hours after the last injection of G-CSF vs. plerixafor. Compared to HBSS (saline) controls, there was a trend towards an increase in the absolute number of monocytes (p=0.09) and lymphocytes (p=0.09) in the blood following plerixafor mobilization (Figure 5A). The absolute number of circulating lymphocytes in the blood following G-CSF mobilization was similar to plerixafor mobilization (p=0.68) although there was a trend towards a higher number of monocytes being mobilized with plerixafor compared to G-CSF (p=0.07). Both mobilizing agents increased absolute circulating granulocyte numbers, but granulocyte numbers in the blood following G-CSF mobilization were significantly higher compared to saline controls (p=0.02) and plerixafor mobilized mice (p=0.007). Similarly, absolute numbers of KLS cells were highest in spleens of G-CSF treated mice. Spleens of G-CSF treated mice contained a 3.6-fold and a 1.7-fold higher number of KLS cells compared to HBSS controls (p=0.002) and plerixafor treated mice (p=0.07) respectively. Spleens from plerixafor treated mice contained 2.2-fold higher number of KLS cells compared to HBSS controls (p=0.02).

Figure 5. Animal transplant model.

Donor B10.d2 mice were injected subcutaneously with either 10ug G-CSF daily for 5 days, one injection of 100ug plerixafor, or saline control (HBSS). (A) Number of splenocytes and complete blood counts were obtained from G-CSF and plerixafor mobilized donors. (B) The alloreactivity of donor B10.d2 splenocytes in response to ConA blasts derived from C57BL/6 donors was assessed by MLR and showed no significant differences between the three groups. (C) Incidence of skin GVHD in recipients receiving 15×106 mobilized total unfractionated splenocytes (p<0.05 G-CSF compared to HBSS controls).

Compared to saline controls, spleen sizes appeared grossly similar following plerixafor mobilization and were larger following G-CSF mobilization (Figure S1A). There was an approximately 2-fold increase in the number of cells contained within the spleen following mobilization with G-CSF compared to saline controls (p<0.001). Splenocyte cell numbers following plerixafor also increased significantly (p=0.04) compared to saline controls, although this increase was smaller than that observed with G-CSF (Figure 5A). The higher number of splenocytes observed in G-CSF mobilized spleens was mostly due to an increase in the number of splenic granulocytes.

To identify cellular phenotypic differences that might impact GVHD and GVL, mobilized splenocytes were harvested and stained with cell specific differentiation markers. The percentage of splenocytes expressing T cell, NK cell, B cell, and granulocyte markers after plerixafor mobilization were similar to saline control injected animals (Table III). In contrast, animals mobilized with G-CSF had a significantly higher percentage of splenic granulocytes, a significantly lower percentage of CD4+ T cells, B cells, and a similar number of CD8+ T cells compared to plerixafor injected animals. There was no difference in the percentage of regulatory CD4+/FoxP3+ T cells mobilized between any of the groups (Table III). Furthermore, CD4+ T cells mobilized with plerixafor had similar proliferation against MHC-mismatched cells as was observed with CD4+ T cells mobilized with G-CSF or CD4+ T cells obtained from saline controls (Figure 5B). Similar to human T cells, a decline in CD62L expression was observed on murine T cells following mobilization with G-CSF (Figure S1B).

Table III.

Phenotype of mobilized splenic lymphocytes

| HBSS | G-CSF | Plerixafor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 T cells | 21.2±4.1 | 15.9±3.1* | 20.3±3.5 |

| CD4 T cells | 12.1±2.6 | 8.9±1.4* | 12.4±2.9 |

| CD8 T cells | 6.9±1.9 | 5.2±2.1 | 6.4±1.6 |

| Treg cells | 1.7±0.03 | 1.7±0.2 | 1.8±0.3 |

| NK cells | 3.0±0.8 | 2.5±0.8 | 3.1±0.9 |

| B cells | 52.5±12.8 | 39.2±9.4** | 51.5±8.6 |

| Granulocytes | 6.1±2.1 | 20.8±5.6* | 7.5±2.8 |

Values are represented as percentage ± standard deviation from 13–18 donors in each group.

p<0.05 compared to HBSS and Plerixafor mobilization.

p<0.05 compared to HBSS controls.

Comparison of transplant outcome in a murine MHC-matched transplantation model using allografts mobilized with plerixafor vs. G-CSF

BALB/c recipient mice were conditioned with total body irradiation then were transplanted intravenously with 15 × 106 splenocytes following mobilization with G-CSF vs. plerixafor. To compensate for the higher CD4+ T cell numbers in the spleens of plerixafor mobilized mice, experiments were also conducted in which transplant recipients had the lymphocyte dose adjusted to 2 × 106 CD4 positive T cells combined with 13×106 CD4 negative splenocytes mobilized with either G-CSF or plerixafor.

Lymphoid and myeloid chimerism assessed 30 days after transplantation by flow cytometry was >90% donor in origin in BALB/c recipients of G-CSF (n=6) and plerixafor mobilized splenocytes (n=6). The incidence of skin GVHD in recipients of plerixafor and saline mobilized splenocytes was comparable. In contrast, recipients of G-CSF mobilized splenocytes had a reduced incidence of skin GVHD compared to recipients of either plerixafor or saline mobilized splenocytes (p=0.02, Fishers test; p<0.05, log-rank test) (Figure 5C). Furthermore, recipients of G-CSF mobilized splenocytes had significantly less weight loss on day 15 post transplantation compared with mice transplanted with HBSS mobilized splenocytes (p=0.002) and mice transplanted with Plerixafor mobilized splenocytes (p=0.04). When the number of transplanted CD4+ T cells was normalized to 2×106 cells across all 3 groups, recipients of G-CSF mobilized splenocytes still had a significantly lower incidence (7/15 recipients developed GVHD within day +60; p<0.05) of skin GVHD compared to plerixafor (16/17 recipients developed GVHD within day +60) or saline mobilized mice (16/17 recipients developed GVHD within day +60). Furthermore, total clinical GVHD scores were significantly lower (p<0.05) in recipients of G-CSF mobilized splenocytes (1.6±0.3) compared to recipients of plerixafor (2.9±0.5) or saline mobilized splenocytes (2.7±0.4).

DISCUSSION

Although G-CSF mobilization is known to alter the phenotype and cytokine polarization of transplanted T cells, the effects of plerixafor mobilization on T cells have not been well characterized. This study provides the first detailed analysis of both phenotypic and functional properties of lymphocytes mobilized with plerixafor. In this study, we show that alterations in T cell phenotype and cytokine gene expression profiles characteristic of G-CSF mobilization do not occur following mobilization with plerixafor.

G-CSF and plerixafor mobilized a similar number of T cells into circulation. As reported by others, we observed the expression of CD62L on T cells to decline following G-CSF mobilization (30). In contrast, we observed no change in T cell phenotypic markers including CD62L expression following plerixafor mobilization. Normally, CD62L negative T cells are effector memory cells; in contrast to CD62L positive T cells, transplantation of CD62L negative T cells does not appear to cause GVHD in murine models (31). The impact of transplanting higher numbers of CD62L positive T cells using allogeneic grafts is unknown. While animal models might suggest the incidence of GVHD could increase, it is important to consider that CD62L expression on CD3+ T cells alone may not reflect the true subtype of T cells. Studies have also shown that serum soluble L-selectin levels are increased after G-CSF mobilization (32) and that some CD62L loss can be reversed with in-vitro incubation (30). Based on this observation, it is possible that the lower levels of CD62L found on G-CSF mobilized T cells occur as a consequence of shedding, rather than reflecting preferential mobilization of an effector type T cell. Although no kinetic studies on CD62L status were performed in our study, CD62L shedding following G-CSF treatment has previously been established to be a temporary phenomenon. Importantly, following mobilization with either plerixafor vs. G-CSF, no differences in the percentage of T cells expressing CD45RA or CCR7, markers of naïve (both) and central memory (CCR7) cells was observed. While the expression of CD27 on plerixafor mobilized T cells did not change, a significant decrease in CD27 expression was observed in G-CSF mobilized CD8+, but not CD4+ T cells. The functional consequence of higher numbers of CD27 negative CD8 T cells using allogeneic grafts is unknown. CD27 binds CD70 and is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity and was recently shown to augments CD8+ T-cell activation (33–34). One might therefore speculate that allografting of G-CSF mobilized CD8+ T cells result in reduced GVHD.

G-CSF mobilization has been shown to skew T cells towards a Th2-type phenotype characterized by increased expression of IL-4 and IL-10 and decreased IFN-γ production. Th2-type T cells are thought to be associated with a lower risk of causing acute GVHD but may play a part in contributing to the increased incidence of chronic GVHD which occurs with the use of G-CSF mobilized allografts compared to bone marrow transplants. We found that T cells mobilized with plerixafor did not display any changes in Th1 and Th2-type cytokines following non-specific mitogen stimulation (data not shown). However, similar to G-CSF mobilized T-cells, we did observe a small reduction in responsiveness to allogeneic stimuli in vitro by 3H-thymidine uptake MLR in plerixafor-mobilized T-cells. Only minor changes in serum levels of IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ were found in mice receiving G-CSF compared to HBSS treated controls. However, we did observe significant decrease in serum levels of IL-8 in donors mobilized with G-CSF (data not shown). Similar to this observation, investigators have previously reported that IL-8 levels decline in patients with esophageal cancer following treatment with G-CSF (35). Recombinant IL-8 is known to directly suppresses the spontaneous production of IL-4 by CD4+ T cells (36). Taken altogether, these data suggest that G-CSF-mediated reductions in serum levels of IL-8 may lead to a shift towards a Th2 phenotype in CD4+ cells potentially accounting for the reduced incidence of GVHD observed in this cohort

Remarkably, the cytokine gene expression profiles related to Th1/ Th2/ Th3 pathways differed significantly in T cells mobilized with these 2 different agents. Real-time PCR assays showed T cells mobilized with plerixafor had cytokine gene expression patterns that were similar to non-mobilized T cells. In contrast, G-CSF altered a number of cytokine-related genes in mobilized CD3+ T cells including both TH1 and TH2 cytokine related genes, transcription factors, and genes regulating T cell activation. Numerous prior studies have also reported that G-CSF induces alterations in cytokine related genes. G-CSF mobilized allografts contain more than a log higher T cell dose than bone marrow allografts but are not associated with an increased incidence of acute GVHD. This has led investigators to speculate that G-CSF induced alterations in cytokines inhibit T cells from causing acute GVHD. Franze et. al (37) showed G-CSF mobilization increased gene expression of the Th2 related gene GATA3 in CD4+ T cells, with this effect being less apparent in non-sorted CD3+ cell fractions. In our analysis, GATA3 levels in T cells did not change significantly in CD3+ T cells following G-CSF mobilization, although our genotype study did not include an analysis that was specific for the CD4+ T cell subset. Recent data suggest reductions in Th17 cells may be partially responsible for the avoidance of acute GVHD in G-CSF mobilized allografts (38). However, using a Luminex array analysis, we observed no changes in serum IL-17 levels following G-CSF mobilization. Instead, serum levels of G-CSF, IL1Rα, IL-4, and MIP-1β increased significantly from baseline following G-CSF mobilization. In contrast to these findings, we observed no significant changes in any of these or other serum cytokines or chemokines measured following plerixafor mobilization (data not shown).

Increasing data suggest regulatory T cells play an important role in regulating GVHD after a-HCT. Transplanting PBSC allografts that contain higher doses of Tregs has been associated with a reduced incidence of GVHD (39–41). In preclinical murine models of a-HCT, injection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells was shown to suppress the early expansion of alloreactive donor T cells and their capacity to induce GVHD without abrogating graft-vs-tumor effector function (42).Furthermore, data in humans has shown that supplementation of allografts with donor Tregs reduces the risk of acute GVHD following haploidentical a-HCT (43). Consistent with these observations, a number of studies have recently reported that regulatory T cell numbers are decreased in patients who develop cGVHD (29, 44). Therefore, we measured the percentage of Tregs mobilized in mice and also measured FoxP3 gene expression in human CD4+ T cells following plerixafor vs. G-CSF administration. In mice, there was no significant difference in the percentage of regulatory CD4+/FoxP3+ T cells mobilized with either G-CSF or plerixafor. Further, HBSS-, G-CSF-, or plerixafor –mobilized murine regulatory T cells did not differ in their suppressive activity of anti-CD3 stimulated T cells in 3H-thymidine proliferation assays (data not shown). Furthermore, in humans FoxP3 gene expression levels did not change significantly from baseline and were similar in G-CSF and plerixafor mobilized CD4+ T cells. Based on these data, one would expect any impact that Tregs will have on GVHD would not differ significantly between allografts mobilized with plerixafor vs. G-CSF.

Because plerixafor does not alter the phenotype and cytokine polarization of T-lymphocytes, one might postulate the T cell mediated immune sequelae of allogeneic transplantation may differ when allografts are mobilized with plerixafor compared to G-CSF. To better interpret the clinical relevance of transplanting T cells with these differences, we explored a murine model of peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in which transplant recipients received a T cell replete plerixafor vs. G-CSF mobilized allograft from MHC matched, minor histocompatibility mismatched donors. A single injection of plerixafor resulted in the rapid mobilization of KLS (c-Kit+/Lin-/sca-1+) hematopoietic stem cells into the peripheral blood of B10.d2 donor mice. The phenotype and MLR reactivity to allo-antigens of T cells mobilized into the spleen with plerixafor was similar to T cells mobilized with G-CSF and non-mobilized T cell splenocytes. However, the CD4+ T cell content was lower in G-CSF mobilized splenocytes and recipients of G-CSF mobilized cells displayed a lower incidence of GVHD compared to recipients transplanted with plerixafor mobilized cells. Importantly, the cumulative incidence of GVHD was still lower in recipients of G-CSF mobilized grafts even when the transplanted number of CD4+ T cells was matched between cohorts. Of note, the incidence of GVHD did not differ between recipients of plerixafor mobilized splenocytes compared to recipients of non-mobilized splenocytes. Transplanting large numbers of T cells that do not undergo changes in their cytokine gene expression profiles in contrast to transplanting T-cells that undergo cytokine changes following G-CSF mobilization could potentially account for the higher incidence of acute GVHD observed in this analysis with plerixafor mobilized allografts. Since CXCR4 is expressed on many different hematopoietic cells, changes in the homing capacity of leukocytes mobilized with plerixafor or G-CSF might also have an impact on GVHD-induction. To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the whether CXCR4 antagonists impact the risk of GVHD by altering leukocyte migratory patterns. However, the magnitude and clinical significance of this effect with plerixafor mobilized lymphocytes would likely be low given the rapidly reversible nature of CXCR4 inhibition with this agent.

In conclusion, our results show important differences in the cellular composition of products mobilized with plerixafor compared to G-CSF. Although in vitro alloreactivity by MLR was similar, phenotypic, genotypic and functional differences characterize T cells mobilized with plerixafor compared to G-CSF. Based on these data, one could hypothesize that immune reconstitution, GVT, and acute and chronic GVHD might differ in recipients receiving peripheral blood stem cell transplants mobilized with plerixafor compared to G-CSF.. A pilot trial evaluating plerixafor for the mobilization and transplantation of HLA matched sibling donor hematopoietic stem cells was recently reported. Although preliminary results from this trial have reported a similar incidence of acute and chronic GVHD and relapse rates as observed with historical controls receiving allografts mobilized with G-CSF (45), larger patient numbers will be needed to evaluate the true impact of plerixafor mobilization on engraftment, immune reconstitution and other immune mediated transplant events. Finally, since it is possible that plerixafor administered concurrently with G-CSF may be used for allogeneic stem cell donors who fail to mobilize sufficient CD34+ cells with G-CSF alone, the effect of combining both mobilizing agents on T cell function will also need to be analyzed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Hematology Branch, and the Swedish and European Research Councils (A.L.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Larochelle A, Krouse A, Metzger M, Orlic D, Donahue RE, Fricker S, Bridger G, Dunbar CE, Hematti P. AMD3100 mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells with long-term repopulating capacity in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2006;107:3772–3778. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moncada V, Bolan C, Yau YY, Leitman SF. Analysis of PBPC cell yields during large-volume leukapheresis of subjects with a poor mobilization response to filgrastim. Transfusion. 2003;43:495–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez C, Urbano-Ispizua A, Marin P, Merino A, Rovira M, Carreras E, Montserrat E. Efficacy and toxicity of a high-dose G-CSF schedule for peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization in healthy donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1273–1278. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Champlin RE, Schmitz N, Horowitz MM, Chapuis B, Chopra R, Cornelissen JJ, Gale RP, Goldman JM, Loberiza FR, Jr., Hertenstein B, Klein JP, Montserrat E, Zhang MJ, Ringden O, Tomany SC, Rowlings PA, Van Hoef ME, Gratwohl A. Blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic cells for allogeneic transplantation. IBMTR Histocompatibility and Stem Cell Sources Working Committee and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Blood. 2000;95:3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mielcarek M, Torok-Storb B. Phenotype and engraftment potential of cytokine-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Curr Opin Hematol. 1997;4:176–182. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199704030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couban S, Simpson DR, Barnett MJ, Bredeson C, Hubesch L, Howson-Jan K, Shore TB, Walker IR, Browett P, Messner HA, Panzarella T, Lipton JH. A randomized multicenter comparison of bone marrow and peripheral blood in recipients of matched sibling allogeneic transplants for myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2002;100:1525–1531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bensinger WI, Martin PJ, Storer B, Clift R, Forman SJ, Negrin R, Kashyap A, Flowers ME, Lilleby K, Chauncey TR, Storb R, Appelbaum FR. Transplantation of bone marrow as compared with peripheral-blood cells from HLA-identical relatives in patients with hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:175–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powles R, Mehta J, Kulkarni S, Treleaven J, Millar B, Marsden J, Shepherd V, Rowland A, Sirohi B, Tait D, Horton C, Long S, Singhal S. Allogeneic blood and bone-marrow stem-cell transplantation in haematological malignant diseases: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaise D, Kuentz M, Fortanier C, Bourhis JH, Milpied N, Sutton L, Jouet JP, Attal M, Bordigoni P, Cahn JY, Boiron JM, Schuller MP, Moatti JP, Michallet M. Randomized trial of bone marrow versus lenograstim-primed blood cell allogeneic transplantation in patients with early-stage leukemia: a report from the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:537–546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigorito AC, Azevedo WM, Marques JF, Azevedo AM, Eid KA, Aranha FJ, Lorand-Metze I, Oliveira GB, Correa ME, Reis AR, Miranda EC, de Souza CA. A randomised, prospective comparison of allogeneic bone marrow and peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation in the treatment of haematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:1145–1151. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klangsinsirikul P, Russell NH. Peripheral blood stem cell harvests from G-CSF-stimulated donors contain a skewed Th2 CD4 phenotype and a predominance of type 2 dendritic cells. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:495–501. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloand EM, Kim S, Maciejewski JP, Van Rhee F, Chaudhuri A, Barrett J, Young NS. Pharmacologic doses of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor affect cytokine production by lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2000;95:2269–2274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan L, Delmonte J, Jr., Jalonen CK, Ferrara JL. Pretreatment of donor mice with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor polarizes donor T lymphocytes toward type-2 cytokine production and reduces severity of experimental graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1995;86:4422–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartung T, Docke WD, Gantner F, Krieger G, Sauer A, Stevens P, Volk HD, Wendel A. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment on ex vivo blood cytokine response in human volunteers. Blood. 1995;85:2482–2489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schols D, Este JA, Henson G, De Clercq E. Bicyclams, a class of potent anti-HIV agents, are targeted at the HIV coreceptor fusin/CXCR-4. Antiviral Res. 1997;35:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatse S, Princen K, Bridger G, De Clercq E, Schols D. Chemokine receptor inhibition by AMD3100 is strictly confined to CXCR4. FEBS Lett. 2002;527:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peled A, Petit I, Kollet O, Magid M, Ponomaryov T, Byk T, Nagler A, Ben-Hur H, Many A, Shultz L, Lider O, Alon R, Zipori D, Lapidot T. Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science. 1999;283:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kollet O, Spiegel A, Peled A, Petit I, Byk T, Hershkoviz R, Guetta E, Barkai G, Nagler A, Lapidot T. Rapid and efficient homing of human CD34(+)CD38(−/low)CXCR4(+) stem and progenitor cells to the bone marrow and spleen of NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID/B2m(null) mice. Blood. 2001;97:3283–3291. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liles WC, Broxmeyer HE, Rodger E, Hubel K, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Bridger G, Henson G, Calandra G, Dale DC. Leucocytosis and mobilization of pluripotent hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers induced by single dose administration of AMD-3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2001;98:737a. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liles WC, Broxmeyer HE, Rodger E, Wood B, Hubel K, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Bridger GJ, Henson GW, Calandra G, Dale DC. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102:2728–2730. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devine SM, Vij R, Rettig M, Todt L, McGlauchlen K, Fisher N, Devine H, Link DC, Calandra G, Bridger G, Westervelt P, Dipersio JF. Rapid mobilization of functional donor hematopoietic cells without G-CSF using plerixafor, an antagonist of the CXCR4/SDF-1 interaction. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devine SM, Andritsos L, Todt L, Vij R, Bonde J, Hess D, Nolta J, Link D, Bridger G, Calandra G, Dipersio JF. A pilot study evaluating the safety and efficacy of AMD3100 for the mobilization and transplantation of HLA-matched sibling donor hematopoietic stem cells in patients with advanced hematological malignancies. Blood. 2005;106:91A–91A. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang EM, Areman EM, David-Ocampo V, Fitzhugh C, Link ME, Read EJ, Leitman SF, Rodgers GP, Tisdale JF. Mobilization, collection, and processing of peripheral blood stem cells in individuals with sickle cell trait. Blood. 2002;99:850–855. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kammula US, Lee KH, Riker AI, Wang E, Ohnmacht GA, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM. Functional analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes by serial measurement of gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor specimens. J Immunol. 1999;163:6867–6875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnopp C, Rad R, Weidinger A, Weidinger S, Ring J, Eberlein B, Ollert M, Mempel M. Fox-P3-positive regulatory T cells are present in the skin of generalized atopic eczema patients and are not particularly affected by medium-dose UVA1 therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:81–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2007.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundqvist A, McCoy JP, Samsel L, Childs R. Reduction of GVHD and enhanced antitumor effects after adoptive infusion of alloreactive Ly49-mismatched NK cells from MHC-matched donors. Blood. 2007;109:3603–3606. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang H, Churchill G. Estimating p-values in small microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:38–43. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storey J. A direct approach to false discovery rate. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 2002;46:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miura Y, Thoburn CJ, Bright EC, Phelps ML, Shin T, Matsui EC, Matsui WH, Arai S, Fuchs EJ, Vogelsang GB, Jones RJ, Hess AD. Association of Foxp3 regulatory gene expression with graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2004;104:2187–2193. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugimori N, Nakao S, Yachie A, Niki T, Takami A, Yamazaki H, Miura Y, Ueda M, Shiobara S, Matsuda T. Administration of G-CSF to normal individuals diminishes L-selectin+ T cells in the peripheral blood that respond better to alloantigen stimulation than L-selectin- T cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:119–124. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson BE, McNiff J, Yan J, Doyle H, Mamula M, Shlomchik MJ, Shlomchik WD. Memory CD4+ T cells do not induce graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:101–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI17601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arslan O, Akan H, Arat M, Dalva K, Ozcan M, Gurman G, Ilhan O, Konuk N, Beksac M, Uysal A, Koc H. Soluble adhesion molecules (sICAM-1, sL-Selectin, sE-Selectin, sCD44) in healthy allogenic peripheral stem-cell donors primed with recombinant G-CSF. Cytotherapy. 2000;2:259–265. doi: 10.1080/146532400539198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hendriks J, Gravestein LA, Tesselaar K, van Lier RA, Schumacher TN, Borst J. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:433–440. doi: 10.1038/80877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polak ME, Newell L, Taraban VY, Pickard C, Healy E, Friedmann PS, Al-Shamkhani A, Ardern-Jones MR. CD70-CD27 interaction augments CD8+ T-cell activation by human epidermal Langerhans cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1636–1644. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hubel K, Mansmann G, Schafer H, Oberhauser F, Diehl V, Engert A. Increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients with esophageal cancer after perioperative treatment with G-CSF. Cytokine. 2000;12:1797–1800. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gesser B, Lund M, Lohse N, Vestergaad C, Matsushima K, Sindet-Pedersen S, Jensen SL, Thestrup-Pedersen K, Larsen CG. IL-8 induces T cell chemotaxis, suppresses IL-4, and up-regulates IL-8 production by CD4+ T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:407–411. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franzke A, Piao W, Lauber J, Gatzlaff P, Konecke C, Hansen W, Schmitt-Thomsen A, Hertenstein B, Buer J, Ganser A. G-CSF as immune regulator in T cells expressing the G-CSF receptor: implications for transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Blood. 2003;102:734–739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joo YD, Lee WS, Won HJ, Lee SM, Kim HR, Park JK, Park SG, Choi IW, Choi I, Seo SK. G-CSF-treated donor CD4+ T cells attenuate acute GVHD through a reduction in Th17 cell differentiation. Cytokine. 2012;60:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.06.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pabst C, Schirutschke H, Ehninger G, Bornhauser M, Platzbecker U. The graft content of donor T cells expressing gamma delta TCR+ and CD4+foxp3+ predicts the risk of acute graft versus host disease after transplantation of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2916–2922. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rezvani K, Mielke S, Ahmadzadeh M, Kilical Y, Savani BN, Zeilah J, Keyvanfar K, Montero A, Hensel N, Kurlander R, Barrett AJ. High donor FOXP3-positive regulatory T-cell (Treg) content is associated with a low risk of GVHD following HLA-matched allogeneic SCT. Blood. 2006;108:1291–1297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf D, Wolf AM, Fong D, Rumpold H, Strasak A, Clausen J, Nachbaur D. Regulatory T-cells in the graft and the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83:1107–1113. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000260140.04815.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Drago K, Fathman CG, Strober S, Negrin RS. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Terenzi A, Castellino F, Bonifacio E, Del Papa B, Zei T, Ostini RI, Cecchini D, Aloisi T, Perruccio K, Ruggeri L, Balucani C, Pierini A, Sportoletti P, Aristei C, Falini B, Reisner Y, Velardi A, Aversa F, Martelli MF. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zorn E, Kim HT, Lee SJ, Floyd BH, Litsa D, Arumugarajah S, Bellucci R, Alyea EP, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Ritz J. Reduced frequency of FOXP3+ CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2005;106:2903–2911. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devine SM, Vij R, Rettig M, Todt L, McGlauchlen K, Fisher N, Devine H, Link DC, Calandra G, Bridger G, Westervelt P, Dipersio JF. Rapid mobilization of functional donor hematopoietic cells without G-CSF using AMD3100, an antagonist of the CXCR4/SDF-1 interaction. Blood. 2008;112:990–998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.