Abstract

Objective

We sought to determine if the timing of hemoconcentration influences the associated survival.

Background

Indicating a reduction in intravascular volume, hemoconcentration during the treatment of decompensated heart failure (HF) has been associated with reduced mortality. However, it is unclear if this survival advantage stems from the improved intravascular volume or if healthier patients are simply more responsive to diuretics. Rapid diuresis early in the hospitalization should similarly identify diuretic responsiveness, but hemoconcentration this early would not indicate euvolemia if extravascular fluid has not yet equilibrated.

Methods

Consecutive admissions at a single center with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF were reviewed (n=845). Hemoconcentration was defined as an increase in both hemoglobin and hematocrit, then further dichotomized into Early or Late using the midway point of the hospitalization.

Results

Hemoconcentration occurred in 422 (49.9%) patients; 41.5% Early and 58.5% Late. Patients with Late vs. Early hemoconcentration had similar baseline characteristics, cumulative in-hospital loop diuretic administered, and worsening of renal function. However, patients with Late vs. Early hemoconcentration had higher average daily loop diuretic doses (p=0.001), greater weight loss (p<0.001), later transition to oral diuretics (p=0.03), and shorter length of stay (p<0.001). Late hemoconcentration conferred a significant survival advantage (HR=0.74, 95% CI 0.59–0.93, p=0.009) whereas Early hemoconcentration offered no significant mortality benefit (HR=1.0, 95% CI 0.80–1.3, p=0.93) over no hemoconcentration.

Conclusions

Only hemoconcentration occurring late in the hospitalization was associated with improved survival. These results provide further support for the importance of achieving sustained decongestion during treatment of decompensated heart failure.

Keywords: Hemoconcentration, Mortality, Decompensated Heart Failure

Introduction

The primary therapeutic objective in the majority of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is optimization of volume status.(1,2) Unfortunately, determining the optimal stopping point for decongestive therapies remains a major challenge.(1) Notably, the increase in concentration of red blood cells and plasma proteins induced by intravascular volume contraction, known as hemoconcentration, provides a surrogate for changes in intravascular volume status during fluid removal.(3–5) In the setting of ADHF treatment, hemoconcentration appears to identify patients that underwent aggressive decongestion and has been associated with better post-discharge survival.(6–8) However, hemoconcentration merely indicates that the plasma refill rate has been exceeded (i.e., fluid has been removed from the intravascular space faster than it could be replaced by extravascular fluid). As a result, hemoconcentration in isolation does not inform total body volume status. Importantly, previous studies of hemoconcentration focused on hemoconcentration at the time of discharge, a time when overall volume status should have been optimized. As such, the majority of patients with hemoconcentration in these studies had objective evidence of improvement in intravascular volume (hemoconcentration) in addition to having the treating physician deem their overall volume status sufficiently optimized to permit discharge.

Interpretation of these observations is challenging since it is unclear to what degree this survival advantage stems from a cause and effect association with aggressive decongestion, or simply from the fact that hemoconcentration may occur more commonly in patients who are diuretic responsive and are therefore healthier. However, if a patient was diuresed early in an ADHF hospitalization with sufficient rapidity to exceed the plasma refill rate, intravascular volume contraction and hemoconcentration would occur. This would be true even if extravascular volume overload persisted at the time of hemoconcentration. However, as diuresis was slowed (perhaps prematurely in response to the improved signs of intravascular volume status), extravascular fluid would equilibrate leading to recurrence of intravascular volume overload and loss or reduction in the degree of hemoconcentration. Importantly, both early and late hemoconcentration should identify treatment responsive patients. However, the degree of volume optimization achieved over the hospitalization would likely be superior in patients with the peak degree of hemoconcentration in proximity to discharge, when extravascular volume status should be optimized to a greater degree. As a result, comparing the survival of patients with peak hemoconcentration early vs. late in the hospitalization could provide some insight into the relative importance of aggressive decongestion vs. treatment responsiveness in the improved survival associated with hemoconcentration. As such, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the association between the timing of peak hemoconcentration and subsequent survival.

Methods

Consecutive admissions from 2004 to 2009 to non-interventional cardiology and internal medicine services at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania with a primary discharge diagnosis of congestive heart failure were reviewed. Inclusion into this single center study required an admission B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level of > 100 pg/mL within 24 hours of admission along with serial hematocrit (Hct) and hemoglobin (Hgb) levels. In order to focus primarily on the physiology and timing of decongestion, patients with a length of stay < 3 days (who likely underwent limited decongestion) and patients with length of stay > 14 days (who likely had either atypical degrees of congestion or non-diuresis related problems driving the length of stay) were excluded. Patients on renal replacement therapy were also excluded. In the event of multiple hospitalizations for a single patient, only the first admission meeting the above inclusion criteria was retained. Please see Supplementary Figure 1 for additional details on patient selection.

Hemoconcentration was defined as an increase in both Hct and Hgb above admission values at any time during the hospitalization. Two positive markers of hemoconcentration were required to improve the signal to noise ratio and to maintain some consistency with our previous hemoconcentration definition.(7) For the primary analyses, the timing of hemoconcentration was determined by averaging the percentage of the hospital stay that had elapsed at the time of the peak Hct and Hgb, then dichotomizing this into early hemoconcentration (Early HC) and late hemoconcentration (Late HC) using the 50% point. The relative, timing of hemoconcentration was chosen to focus on a patient’s overall improvement in intravascular volume status, rather than the degree of euvolemia achieved after an arbitrary period of time. This distinction is of practical importance for two reasons; 1) the amount of baseline extravascular volume overload present in each patient is highly variable, and 2) extravascular and intravascular volumes are in equilibrium. As a result, intravascular euvolemia will on average take longer to achieve if severe extravascular volume overload was present at baseline and therefore confound the absolute time to peak hemoconcentration by the degree of baseline volume overload. Secondary analysis focused on the absolute time to peak hemoconcentration with adjustment for length of stay.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the four variable Modified Diet and Renal Disease equation.(9) Worsening renal function (WRF) was defined as a ≥ 20% decrease in eGFR at any time during the hospitalization.(7,10–14) All-cause mortality was determined via the Social Security Death Index.(15) Loop diuretic doses were converted to furosemide equivalents with 1 mg bumetanide = 20 mg torsemide = 80 mg furosemide for oral diuretics, and 1 mg bumetanide = 20 mg torsemide = 40 mg furosemide for intravenous diuretics. Average daily loop diuretic doses were calculated by dividing the total dose of loop diuretics over the hospitalization (in furosemide equivalents) by the hospital length of stay. Given that hospital admissions over a 5 year period were analyzed, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken to ensure that the primary findings were consistent over this observation period and thus the cohort could be analyzed as a whole. There was no significant difference in the findings between the 1st quartile enrolled and the 4th quartile enrolled (p interaction=0.52) or continuously across the enrollment interval (p interaction=0.23). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

Statistical Analysis

The primary goal of this analysis was to evaluate the association between timing of hemoconcentration and post-discharge survival. As such, the primary analysis focused on risk for all-cause mortality in patients with Early HC compared to Late HC. Values reported are mean ± SD, median (quartile 1 – quartile 4) and percentile. Independent Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to compare continuous variables. The chi-square test was used to evaluate associations between categorical variables. Proportional hazards modeling was use to evaluate time-to-event associations with all-cause mortality. Candidate covariates entered in the model were baseline characteristics with less than 10% missing values and a univariate association with all-cause mortality at p≤0.2. Covariates that had a p>0.2 but a theoretical basis for potential confounding were forced into the model. Models were built using backward elimination (likelihood ratio test) where all covariates with a p<0.2 were retained.(16) Adjusted survival curves were plotted for patients with Early HC, Late HC, and no HC; and the x axis was terminated when the number at risk was <10%. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the 845 patients meeting inclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. Overall, 422 (49.9%) patients had an increase in both Hgb and Hct from admission to their highest in- hospital level, 323 (38.2%) had no increase, and 100 (11.8%) had an increase in only one of the two. There was a greater incidence of an increase in Hgb (58.5%) than Hct (53.3%). Amongst patients whose Hct and Hgb increased above their admission value, the average increases in Hct and Hgb were 10.2% ± 9.0% and 9.3% ± 9.5%, respectively. Similar to previous studies of hemoconcentration, patients with increases in both Hct and Hgb during hospitalization had parameters consistent with aggressive decongestion including greater volume/weight loss, exposure to loop diuretics, and deterioration in renal function compared to those without any evidence of hemoconcentration (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Overall Cohort | Hemoconcentration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n=845) | Early (n=175) | Late (n=247) | p-value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (y) | 62.6 ± 15.8 | 62.7 ± 17.0 | 60.9 ± 15.2 | 0.123 |

| White race | 34.1% | 41.7% | 33.6% | 0.089 |

| Male | 54.2% | 58.9% | 59.9% | 0.827 |

| Medical History | ||||

| Hypertension | 73.8% | 68.4% | 77.1% | 0.045* |

| Diabetes | 40.3% | 43.7% | 39.2% | 0.357 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 28.3% | 32.2% | 25.5% | 0.134 |

| Coronary artery | 43.3% | 44.3% | 44.1% | 0.98 |

| disease | ||||

| Ischemic etiology | 25.1% | 25.7% | 29.6% | 0.386 |

| Ejection fraction >40% | 34.8% | 32.1% | 31.0% | 0.805 |

| Admission Physical Exam | ||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 89.7 ± 19.8 | 87.8 ± 19.1 | 88.6 ± 18.4 | 0.450 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 138.2 ±34.4 | 134.1 ±34.5 | 135.7± 31.7 | 0.907 |

| Weight (kg) | 90.5 ±29.8 | 86.6 ±29.2 | 93.1 ±28.5 | 0.033* |

| Jugular venous distention | 35.2% | 37.8% | 38.8% | 0.847 |

| Edema | 42.0% | 39.0% | 43.4% | 0.36 |

| Cardiac Function | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 27.5 (15–45) | 26.3 (15–45) | 25 (15–42.5) | 0.771 |

| Moderate or severe mitral regurgitation | 43.20% | 43.40% | 43.00% | 0.934 |

| Cardiac Devices | ||||

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator | 29.1% | 29.9% | 28.6% | 0.410 |

| Biventricular pacemaker | 19.4% | 19.7% | 19.1% | 0.892 |

| Medications (Admission) | ||||

| b-Blocker | 68.0% | 68.0% | 70.4% | 0.591 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 61.4% | 60.6% | 61.1% | 0.907 |

| Digoxin | 23.1% | 24.7% | 27.5% | 0.518 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 15.6% | 17.2% | 17.0% | 0.949 |

| Loop diuretic dose (mg) | 40 (0–80) | 40 (0–80) | 40 (0–80) | 0.907 |

| Medications (Discharge) | ||||

| b-Blocker | 84.8% | 82.6% | 88.1% | 0.113 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 78.3% | 80.7% | 79.8% | 0.828 |

| Digoxin | 22.1% | 23.3% | 23.5% | 0.962 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 20.6% | 20.9% | 25.1% | 0.322 |

| Loop diuretic dose (mg) | 80 (20–160) | 40 (20–120) | 80 (40–160) | 0.021* |

| Laboratory Values | ||||

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 138.5 ± 4.4 | 138.3 ± 4.8 | 138.3 ± 3.9 | 0.991 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 1299 (651– 2435) | 1252 (728– 2085) | 1372 (672– 2665) | 0.316 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 60.3 ± 28.9 | 60.6 ± 28.9 | 64.0 ± 29.8 | 0.232 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28.9 ± 21.6 | 30.0 ± 22.6 | 26.8 ± 19.5 | 0.119 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.1 ± 2.1 | 11.8 ± 2.1 | 11.7 ± 2.0 | 0.691 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.6 ± 6.2 | 35.3 ± 6.3 | 35.3 ± 5.7 | 0.987 |

Significant p-value. ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme, ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, BUN: blood urea nitrogen. Jugular venous distension was determined by the admitting physician by checking “jugular venous distension” on the admission history and physician template form. Edema was defined as any edema greater than trace noted on the admission history and physical form.

The time to peak Hct was 3.8 ± 2.8 days and peak Hgb was 3.8 ± 2.4 days. This equated to the average peak Hct and Hgb occurring 62.7 ± 29.5% through the hospitalization, with 41.5% of patients having peak hemoconcentration in the first 50% of the hospitalization (Early HC) and 58.5% with peak hemoconcentration after the 50% mark (Late HC). In patients with Early HC the median time to peak in both hemoglobin and hematocrit was 2 days (IQR 1 – 3 days) in the Early HC group and 4 days (IQR 3 to 6 days) in the Late HC group. Overall, baseline characteristics were similar between patients with Early and Late HC (Table 1). The cumulative amount of loop diuretic administered throughout the hospitalization was not significantly different between groups; however, the average daily quantity of both intravenous and total loop diuretic was significantly greater in patients with Late HC compared to Early HC (Table 2). In patients with Early HC, the maximum dose of IV diuretics was administered earlier in the hospital course [25% (IQR 12.5–37.5%) vs. 33% (IQR 20–50%) of the way through the hospitalization, p<0.001] and the transition to oral diuretics also occurred earlier in the hospital course [61% (IQR 39–80%) vs. 67% (IQR 50–83%) of the way through the hospitalization, p=0.034]. The odds of the transition to oral diuretics falling in the first half of the hospitalization was significantly higher for patients with Early HC (OR=2.2, p=0.005). The relative frequency of hypokalemia (serum potassium <3.5 mEq/L; p=0.99) and the daily amount of supplemental potassium administered (p=0.89) was similar between Early and Late HC. The change in eGFR from admission to the worst in-hospital value (Table 2) and the overall incidence of WRF was similar between Late and Early HC (OR=1.1, p=0.65). However, the greatest deterioration in renal function occurred further through the hospital course [33% (IQR 0–67%) vs. 25% (IQR 0–67%) of the way through the hospitalization, p=0.003] and the odds of WRF occurring in the latter 50% of the hospitalization was greater in the Late HC group (OR=2.5, p=0.006). Notably, the total and average daily fluid/weight losses were significantly greater in patients with Late HC, but the length of stay was shorter (Figure 1 A/B). Although the increase from baseline to peak Hct and Hgb was only slightly greater amongst patients with Late vs. Early HC, the baseline to discharge Hct and Hgb was substantially greater in the Late HC group (Figure 2). Notably, in patients with Early HC, hemoconcentration was largely transient such that only 34.5% with an Early HC continued to meet criteria for hemoconcentration at the time of discharge. In patients with Early HC, the average peak to discharge hemodilution (change in Hct = −9.6 ± 8.0%; change in Hgb = −9.0 ± 7.8%) was not different from the initial degree of hemoconcentration in these patients (p>0.61 for both comparisons).

Table 2.

In hospital Treatment Related Parameters

| Overall | Hemoconcentration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | ||||

| (n=845) | Early (n=175) | Late (n=247) | p-value | |

| Diuretic Administration | ||||

| Total loop diuretic (mg) | 400 (200– 820) | 410 (200– 915) | 440 (230– 900) | 0.637 |

| Average total loop diuretic (mg/day) | 80 (40–130) | 66 (36–115) | 90 (50–138) | 0.001* |

| Total IV loop diuretic (mg) | 240 (80–500) | 200 (80–550) | 280 (546– 280) | 0.221 |

| Average IV loop diuretic (mg/day) | 43 (17–85) | 33 (10–69) | 53 (20–70) | 0.001* |

| Maximum 24 hour dose of IV diuretic (mg) | 80 (40–160) | 80 (40–160) | 100 (60–200) | 0.081 |

| Adjuvant thiazide diuretic | 11.3% | 9.8% | 13.4% | 0.256 |

| Total oral loop diuretic (mg) | 120 (0–320) | 160 (0–360) | 120 (0–300) | 0.323 |

| In-hospital inotropes | ||||

| Milrinone | 13.1% | 14.5% | 10.0% | 0.166 |

| Dobutamine | 1.1% | 2.3% | 0.4% | 0.083 |

| In-Hospital Maximum Changes in Laboratory Parameters | ||||

| Hct (%) | 5.4 ± 8.4 | 10.1 ± 10.7 | 10.7 ± 7.8 | 0.012* |

| Hgb (%) | 5.4 ± 8.6 | 9.8 ± 11.2 | 10.6 ± 8.7 | 0.014* |

| eGFR (%) | –15.7 ± 15.1 | –17.1 ± 16.2 | –16.9 ± 15.7 | 0.974 |

| BUN (%) | 39.5 ± 51.0 | 45.1 ± 58.8 | 47.8 ± 55.9 | 0.315 |

| Bicarbonate (%) | 20.1 ± 17.3 | 21.2 ± 19.1 | 20.4 ± 15.5 | 0.902 |

| Admission to Discharge Change in Laboratory Parameters | ||||

| Hct (%) | –2.1 ± 11.0 | 0.3 ± 11.8 | 7.2 ± 8.8 | <0.001* |

| Hgb (%) | –1.8 ± 11.0 | –0.1 ± 11.9 | 7.3 ± 9.5 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (%) | –1.5 ± 56.0 | –2.1 ± 25.5 | 1.3 ± 27.1 | 0.195 |

| BUN (%) | 20.9 ± 50.7 | 22.2 ± 55.7 | 31.6 ± 54.0 | 0.017* |

| Bicarbonate (%) | 10.6 ± 18.9 | 10.9 ± 18.2 | 10.6 ± 18.0 | 0.53 |

| Sodium (%) | –0.7 ± 3.8 | –0.45 ± 3.2 | –1.0 ± 5.3 | 0.688 |

| Hospital Course | ||||

| Length of stay (days) | 5 (4–8) | 7 (4–10) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

Significant p-value. Hct: hematocrit, Hgb: hemoglobin, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, BUN: blood urea nitrogen.

Figure 1. Weight and fluid losses.

Total weight and net fluid lost during hospitalization (1A) and average daily weight and fluid losses (1B) in patients with Early vs. Late hemoconcentration. HC: Hemoconcentration

Figure 2. Degree of admission to peak and admission to discharge hemoconcentration in patients with Early vs. Late hemoconcentration.

HC: Hemoconcentration. Hemoconcentration calculated as the average percentage change in both hemoglobin and hematocrit.

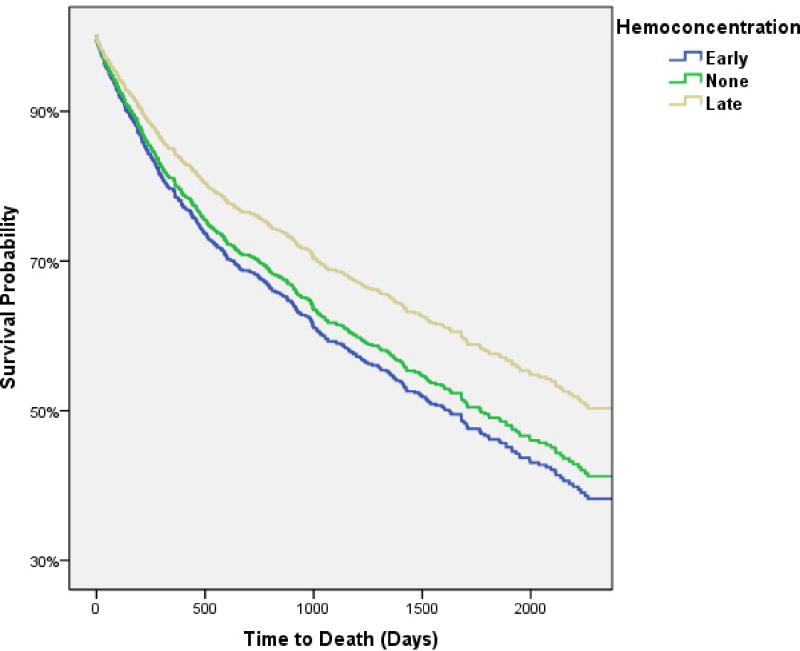

Over a median follow up of 3.4 years (IQR 1.3–5.3 years), 439 (52%) patients died of any cause. The time from hospital admission to ascertainment of all-cause mortality was not significantly different between patients with early, late, or no HC (p=0.2). HC at any time during the hospitalization (i.e., either Early HC or Late HC) was not associated with a significantly better survival both before (HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.70–1.0, p=0.078) and after (HR=0.89, 95% CI 0.72–1.1, p=0.25) adjustment for baseline characteristics (age, race, sex, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, edema, BNP, serum sodium, eGFR, Hgb, Hct, loop diuretic dose, beta blocker use, and coronary artery disease). Interestingly, Late HC was associated with significantly better survival compared to both Early HC (HR=0.73, 95% CI 0.56–0.96, p=0.026) and no HC (HR=0.74, 95% CI 0.59–0.93, p=0.009). Mortality was not different between patients with Early HC and no HC (HR=1.0, 95% CI 0.80–1.3, p=0.93). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, Late HC remained significantly associated with better survival compared to both Early and no HC (Figure 3). The survival advantage with Late HC compared to Early HC remained significant after controlling for the absolute magnitude of admission to peak change in Hct and Hgb and the length of stay (HR=0.69, 95% CI 0.52–0.92, p=0.012). Additionally, extensive adjustment for baseline characteristics, in-hospital treatment related parameters, and discharge medications (the above baseline characteristics plus: length of stay, admission to peak change in Hct and Hgb, net fluid output, total loop diuretic administered, inotrope use, as well as discharge beta-blocker, ACE/ARB, spironolactone, digoxin, and loop diuretic dose) minimally affected these results (HR=0.65, 95% CI 0.45–0.92, p=0.016). Exploratory analysis comparing patients with Late HC that maintained hemoconcentration through discharge (79.4% of Late HC patients, n=196) to Early HC patients that no longer met criteria for hemoconcentration at discharge (62.3% of Early HC patients, n=109) revealed a particularly pronounced survival advantage with sustained Late HC (adjusted for the above admission, in-hospital, and discharge parameters; HR=0.43, 95% CI 0.25–.72, p=0.002).

Figure 3.

Adjusted survival curves of patients with early, late, and no hemoconcentration. Comparison of late hemoconcentration to no hemoconcentration p=0.038, comparison of late hemoconcentration to early hemoconcentration p=0.021, comparison of early hemoconcentration compared to no hemoconcentration p=0.54. Covariates adjusted for: age, race, sex, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, edema, BNP, serum sodium, eGFR, Hgb, Hct, loop diuretic dose, beta blocker use, and coronary artery disease.

Early HC vs. Late HC, defined using an absolute rather than relative time to peak hemoconcentration, was not associated with significant differences in survival (p≥0.16 for all cut points using days 1 through 14). However, these findings were influenced by a significantly longer length of stay in the Late HC groups. For example, defining Late HC using the median time to hemoconcentration (3 days) the length of stay was significantly greater with Late HC vs. Early HC [7 days (5–10) vs. 4 days (3–6), p<0.0001]. After adjustment for length of stay, Late HC (defined using the 3 day cut point, patient characteristics presented in Supplementary Table 2) was associated with significantly better survival than Early HC (HR=0.69, 95% CI 0.51–0.95, p=0.022); an association which persisted after adjustment for admission, in-hospital, and discharge parameters (HR=0.59, 95% CI 0.39–0.89, p=0.011). Notably, Late HC defined as a peak in hemoconcentration occurring at very late time points, such as after 7 days (adjusted HR=0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.93, p=0.028), 8 days (adjusted HR=0.30, 95% CI 0.13–0.71, p=0.007), 9 days (adjusted HR=0.24, 95% CI 0.09–0.66, p=0.006), and 10 days (adjusted HR=0.26, 95% CI 0.07–0.91, p=0.035) was actually associated with a progressively greater survival advantage compared to Early HC.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is that the timing of hemoconcentration during the treatment of decompensated heart failure strongly influences the associated mortality, with significantly better survival with Late HC compared to patients with Early HC or no HC. Interestingly, baseline disease severity indicators, total in-hospital loop diuretics administered, and the overall incidence of WRF were similar between patients with Early and Late HC. However, the pattern of diuretic approach appeared to differ with higher average daily doses of loop diuretics, later transition to oral diuretics, later time to peak deterioration in renal function, and greater fluid and weight loss with Late HC vs. Early HC. Notably, the majority of Early HC patients experienced substantial hemodilution subsequent to their Early HC, such that their discharge Hct and Hgb were similar to the admission values. In conjunction with the lesser degree of overall weight and volume loss, these observations suggest that diuresis may have been deescalated prior to complete elimination of extravascular volume overload in Early HC patients. Overall, these findings indicate that the association between hemoconcentration and better survival is contingent not only on whether hemoconcentration can be induced, but also on the timing/durability of the hemoconcentration.

A basic physiologic principal, removal of intravascular fluid at a rate faster than it can be refilled from extravascular stores will lead to hemoconcentration. This physiology has been employed by nephrologists for decades to monitor intravascular volume status during hemodialysis.(3,4) Analogously, some degree of hemodilution following cessation of fluid removal is also to be expected as extravascular fluid comes to equilibrium with intravascular volume. However, in the setting of ADHF with severe extravascular volume overload, recurrence of intravascular volume overload can be nearly complete after abrupt cessation of early aggressive fluid removal. In a study by Guazzi and colleagues, severely volume-overloaded patients were exposed to a brief period of high rate ultrafiltration (500 cc/hr) resulting in a 22% decrease in plasma volume.(17) Despite a stable weight maintained over the next 48 hours with oral diuretics, plasma volume completely returned to pre-treatment values. Notably, both right and left-sided filling pressures were reduced with the intervention, but unlike plasma volume, filling pressures did not rebound and actually remained at the immediate post-treatment levels. Similarly, in a study by Marenzi and colleagues, 24 hours after removal of 7.5 L of fluid (ultrafiltrate + urine), plasma volume was unchanged from pre-treatment levels, but filling pressures were maintained at the improved immediate post-fluid removal levels.(18) These observations highlight the fact that via the substantial and dynamic compliance of the capacitance vessels of the venous system, filling pressures and blood volume can have little correlation.(19) Importantly, in the study by Marenzi, the mean right atrial pressure 24 hours after ultrafiltration was reduced to approximately 8 mmHg. This indicates that a significant percentage of these patients likely had a normalization of jugular venous pressure despite an unchanged blood volume. As such, it is understandable how transient or even a complete absence of hemoconcentration can occur in the setting of substantial diuresis and how hemoconcentration could be transient even in the setting of continued slower diuresis. These findings reinforce the fact that the vast majority of our surrogates for decongestion, including right heart catheterization parameters and even directly measured blood volume, only provide a snapshot of the intravascular environment rather than a true measure of global decongestion. The implication of this physiology is that application a one size fits all strategy of aggressive diuresis to a prespecified/non-patient specific time to hemoconcentration is unlikely to be successful. Support for this concept is provided by the finding that Late HC defined in absolute terms (i.e., number days to hemoconcentration) was only associated with better survival after adjustment for length of stay.

The association between hemoconcentration and improved survival provides reassurance that the net clinical benefit from aggressive decongestion may outweigh the adverse effects of decongestive therapies.(6,7) However, interpretation of this observational data is challenging since it is unclear to what degree the improved survival results directly from the aggressive decongestion or if patients that respond to treatment with hemoconcentration are healthier patients. Given that diuretic resistance is a powerful prognostic indicator, it is intuitive that patients responding to diuretics with an effective diuresis may have lower disease severity.(20–22) There are several findings in the current analysis that argue that this is not the primary factor driving these observations. 1) Both Early and Late HC patients were likely diuretic responsive since they both hemoconcentrated. Notably, the group with Early HC actually hemoconcentrated with less aggressive treatment. 2) Early HC patients had similar maximum IV loop diuretic doses, but earlier administration of that maximum dose and an earlier transition to oral diuretics. This suggests that the inability to maintain hemoconcentration was not purely a function of a greater degree of diuretic refractoriness. 3) Baseline characteristics were remarkably similar, but essentially all in-hospital treatment related parameters trended toward a more sustained/aggressive diuresis in the Late HC group. 4) Mortality differences between groups persisted after extensive adjustment for baseline, in hospital, and discharge parameters. These findings lend incremental support to the concept that association between hemoconcentration and improved survival is not solely driven by treatment refractoriness in the comparison group.

Although it seems probable that there was a difference in the timing of de-escalation of therapy between the Early HC and Late HC groups, which was probably not primarily driven by diuretic refractoriness, the motivation for this de-escalation is unknown. Although admission, discharge, and available non-diuretic in-hospital characteristics were similar between groups; differences in the ability to tolerate therapy may have emerged during treatment. As a result, assumption that more aggressive/sustained diuresis in the Early HC group would have led to improved outcomes may be incorrect. For example, factors such as hypotension, WRF, adequacy of perfusion, or even a general ill-appearance of the patient can (appropriately) factor into the physician’s decision-making regarding subsequent diuretic therapy. As such, early de-escalation of therapy could have resulted from a physician’s erroneous conclusion that the patient no longer required diuresis, or the astute recognition that the patient could no longer tolerate further diuresis. As a result, it is possible that the differences in survival were derived from differences in the ability of the patients to tolerate sustained aggressive diuresis rather than the sustained diuresis itself.

Limitations

There are several limitations that must be considered when interpreting these results. First, given the observational nature of this study, causality is impossible to demonstrate and residual confounding cannot be excluded. Furthermore, the data were generated from a single center and given that local practice patterns can vary across institutions, it is possible that these findings will not generalize to other centers. Due to the modest size of our cohort, the ability to rule out temporal variations in the association between Early HC and Late HC with mortality is limited. Larger studies will be needed to determine if changing practice patterns over time influence these observations. Additionally, exclusion of patients that did not have a baseline B-type natriuretic peptide level available further limits generalizability. Serial measures of total protein and albumin were not available in this population, markers which appear to have better operating characteristics than Hct and Hgb.(7) Notably, in previous reports, Hct alone was not significantly associated with WRF or mortality (7) and Hgb alone did not remain significantly associated with mortality after multivariate adjustment in a different study.ENREF 7(6) Although this limitation was likely overcome somewhat by increasing the number of patients studied (N<340 in the previous studies) and using both Hct and Hgb to define hemoconcentration, it is unclear if the results would differ significantly if total protein and albumin had been available. Furthermore, the primary assumption is that increases or decreases in the concentration of Hct, Hgb, and plasma proteins are predominantly driven by changes in volume status, but this has never been tested. Factors such as bleeding, phlebotomy, and the rate of production of new red blood cells have an uncertain influence and we cannot exclude the possibility that these factors do not similarly affect Early HC and Late HC and thus the lack of availability of these parameters is a significant limitation to the study. Although the analyses herein may provide proof of concept when analyzed in large cohorts, on the individual patient level, biological and assay variability will likely preclude serial Hct and Hgb measures as a reliable gauge of intravascular volume shifts. Although total and peak doses of IV diuretics did not support the hypothesis that the Early HC group was highly diuretic resistant, these are crude metrics to assess diuretic responsiveness and it is possible that there were differences between groups that may have influenced outcomes. Additionally, the lack of data on rehospitalizations is a significant limitation. Perhaps most importantly, the observational nature of this study makes it impossible to exclude the possibility that patients with Early HC were not just “sicker” and the observed differences in survival actually had little to do with the aggressiveness of diuresis. As a result of the above limitations, our findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and serve primarily to motivate further consideration of randomized trials of decongestive strategies which can address causality.

Conclusion

The association between hemoconcentration and survival is strongly influenced by the timing at which peak hemoconcentration occurs, with better survival in patients with late hemoconcentration compared to early or no hemoconcentration. It cannot be determined from these data to what degree an aggressive sustained diuretic strategy vs. a durable response to that strategy drove these observations. However, these data do suggest that even when initial diuresis is rapid enough to produce hemoconcentration, if it is not maintained at a rate adequate to progressively contract plasma volume throughout the hospitalization, outcomes are inferior. Given that volume management is the primary therapeutic objective in most decompensated heart failure admissions, and its completeness may have substantial influence on subsequent outcomes, additional research is necessary to develop more objective and reproducible therapeutic endpoints.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Diagram of patient selection process.

Supplementary Table 1: In-hospital treatment related parameters between patients with or without hemoconcentration at any time

Supplementary Table 2: Characteristics of patients with Early vs. Late hemoconcentration defined by an absolute time to hemoconcentration of ≥3 days.

Acknowledgments

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Funding Sources: NIH Grant 5T32HL007843-15, 1K23HL114868-01, and K24DK090203

Selected Abbreviations

- ADHF

Acute decompensated heart failure

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- Hgb

Hemoglobin

- Hct

Hematocrit

- HC

Hemoconcentration

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- WRF

Worsening renal function

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, De Luca L, Burnett J. Congestion in acute heart failure syndromes: an essential target of evaluation and treatment. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119:S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams KF, Jr, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Am Heart J. 2005;149:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneditz D, Pogglitsch H, Horina J, Binswanger U. A blood protein monitor for the continuous measurement of blood volume changes during hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1990;38:342–346. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leypoldt JK, Cheung AK, Steuer RR, Harris DH, Conis JM. Determination of circulating blood volume by continuously monitoring hematocrit during hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1995;6:214–219. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V62214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle A, Sobotka PA. Redefining the therapeutic objective in decompensated heart failure: hemoconcentration as a surrogate for plasma refill rate. J Card Fail. 2006;12:247–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davila C, Reyentovich A, Katz SD. Clinical correlates of hemoconcentration during hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2011;17:1018–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Testani JM, Chen J, McCauley BD, Kimmel SE, Shannon RP. Potential effects of aggressive decongestion during the treatment of decompensated heart failure on renal function and survival. Circulation. 2010;122:265–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Meer P, Postmus D, Ponikowski P, et al. The predictive value of short term changes in hemoglobin concentration in patients presenting with acute decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol Epub Mar. 13 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Testani JM, McCauley BD, Kimmel SE, Shannon RP. Characteristics of patients with improvement or worsening in renal function during treatment of acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1763–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Testani JM, McCauley BD, Chen J, Shumski M, Shannon RP. Worsening renal function defined as an absolute increase in serum creatinine is a biased metric for the study of cardio-renal interactions. Cardiology. 2010;116:206–12. doi: 10.1159/000316038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Testani JM, Kimmel SE, Dries DL, Coca SG. Prognostic importance of early worsening renal function after initiation of Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Circulation Heart failure. 2011;4:685–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Testani JM, Coca SG, McCauley BD, Shannon RP, Kimmel SE. Impact of changes in blood pressure during the treatment of acute decompensated heart failure on renal and clinical outcomes. European journal of heart failure. 2011;13:877–84. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testani JM, Cappola TP, McCauley BD, et al. Impact of worsening renal function during the treatment of decompensated heart failure on changes in renal function during subsequent hospitalization. Am Heart J. 2011;161:944–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn J, Kramer N, McDermott D. Validation of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI): An Important Readily-Available Outcomes Database for Researchers. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9:6–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guazzi MD, Agostoni P, Perego B, et al. Apparent paradox of neurohumoral axis inhibition after body fluid volume depletion in patients with chronic congestive heart failure and water retention. Br Heart J. 1994;72:534–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.72.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marenzi G, Lauri G, Grazi M, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, Agostoni P. Circulatory response to fluid overload removal by extracorporeal ultrafiltration in refractory congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:963–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelman S. Venous function and central venous pressure: a physiologic story. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:735–748. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181672607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neuberg GW, Miller AB, O’Connor CM, et al. Diuretic resistance predicts mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. Am Heart J. 2002;144:31–8. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Testani JM, Cappola TP, Brensinger CM, Shannon RP, Kimmel SE. Interaction between loop diuretic-associated mortality and blood urea nitrogen concentration in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasselblad V, Gattis Stough W, Shah MR, et al. Relation between dose of loop diuretics and outcomes in a heart failure population: results of the ESCAPE trial. European journal of heart failure : journal of the Working Group on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. 2007;9:1064–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Diagram of patient selection process.

Supplementary Table 1: In-hospital treatment related parameters between patients with or without hemoconcentration at any time

Supplementary Table 2: Characteristics of patients with Early vs. Late hemoconcentration defined by an absolute time to hemoconcentration of ≥3 days.