Summary

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a motor neuron degenerative disease characterized by a progressive, and ultimately fatal, muscle paralysis. The human VAMP-Associated Protein B (hVAPB) is the causative gene of ALS type 8. Previous studies have shown that a loss-of-function mechanism is responsible for VAPB-induced ALS. Recently, a novel mutation in hVAPB (V234I) has been identified but its pathogenic potential has not been assessed. We found that neuronal expression of the V234I mutant allele in Drosophila (DVAP-V260I) induces defects in synaptic structure and microtubule architecture that are opposite to those associated with DVAP mutants and transgenic expression of other ALS-linked alleles. Expression of DVAP-V260I also induces aggregate formation, reduced viability, wing postural defects, abnormal locomotion behavior, nuclear abnormalities, neurodegeneration and upregulation of the heat-shock-mediated stress response. Similar, albeit milder, phenotypes are associated with the overexpression of the wild-type protein. These data show that overexpressing the wild-type DVAP is sufficient to induce the disease and that DVAP-V260I is a pathogenic allele with increased wild-type activity. We propose that a combination of gain- and loss-of-function mechanisms is responsible for VAPB-induced ALS.

Keywords: ALS, Drosophila, Genetics, Neurodegeneration, VAPB

Introduction

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the degeneration of motor neurons leading to muscle atrophy, spasticity and, eventually, death. ALS is traditionally classified into two categories: familial ALS (FALS) and sporadic ALS (SALS) (Pasinelli and Brown, 2006). Missense mutations (P56S and T46I) at the N-terminal region of the human VAMP-associated protein B gene (hVAPB) have been identified in both patients with FALS and SALS (Nishimura et al., 2004; Funke et al., 2010; Millecamps et al., 2010; Landers et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010). VAP proteins contain an N-terminal domain, which is highly homologous to the nematode major sperm protein (MSP), a central domain that forms a coiled-coil structure and a C-terminal transmembrane domain (Nishimura et al., 1999; Kaiser et al., 2005).

Members of the highly conserved VAP family have been involved in a number of seemingly unrelated functions including regulation of ER morphology, lipid transfer, vesicular trafficking and dendritic morphogenesis (Soussan et al., 1999; Skehel et al., 2000; Amarilio et al., 2005; Teuling et al., 2007; Lev et al., 2008; Peretti et al., 2008; Kuijpers et al., 2013a). DVAP, the Drosophila orthologue of hVAPB, controls synaptic structure, microtubule cytoskeleton architecture and composition of post-synaptic glutamate receptors (Pennetta et al., 2002; Chai et al., 2008). In C. elegans and Drosophila, the MSP domain is cleaved, secreted and acts as a ligand for Robo and Lar-like receptors to control muscle mitochondria morphology, localization and function (Tsuda et al., 2008; Han et al., 2012). Previous studies have implicated ALS mutant alleles in an abnormal unfolded protein response and in the disruption of the anterograde axonal transport of mitochondria (Chen et al., 2010; Kanekura et al., 2006; Langou et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2009; Gkogkas et al., 2008; Mórotz et al., 2012). Transgenic expression in Drosophila of either DVAP-P58S or DVAP-T48I, two ALS-linked alleles, mirrors major hallmarks of the human disease including neurodegeneration, aggregate formation, locomotion defects and chaperone upregulation (Chai et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010). Several lines of evidence support the notion that P56S mutation is a loss-of-function mutation, possibly via a dominant negative effect. P56S mutant protein forms aggregates in which the wild-type protein is recruited (Teuling et al., 2007). This together with the analysis of mutant phenotypes associated with transgenic expression of the P56S protein in several disease models, confirms that P56S is a loss-of-function mutation (Teuling et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Chai et al., 2008; Ratnaparkhi et al., 2008; Tsuda et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2009; Forrest et al., 2013; Kuijpers et al., 2013a). Furthermore, a reduction in VAP protein levels has been reported in sporadic ALS patients, SOD1 (Superoxide dismutase 1) mutant mice as well as in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from ALS patients (Anagnostou et al., 2010; Teuling et al., 2007; Mitne-Neto et al., 2011). Recently, a novel mutation in the gene hVAPB was identified in one ALS patient who has also a pathogenic repeat expansion in C9ORF72 (chromosome 9 open reading frame 72), another ALS causative gene. The mutation within the hVAPB gene replaces the Valine at the position 234 of the highly conserved transmembrane domain with an Isoleucine (V234I in humans and V260I in Drosophila) (van Blitterswijk et al., 2012). Moreover, no information is available about the dominant or recessive inheritance of the mutation in humans and theoretical predictions based on bioinformatics approaches give contradictory results as to whether V234I mutation has a damaging effect on the function of the protein (van Blitterswijk et al., 2012; Ingre et al., 2013). To directly assess the pathogenic effect of this mutation and to unveil potential new mechanisms of disease pathogenesis, we carried out a series of functional studies in a well-established Drosophila model of ALS.

Here we report that transgenic expression of DVAP-V260I recapitulates major hallmarks of the human disease including aggregate formation, reduced viability, neuromuscular defects, abnormal locomotion behavior, neurodegeneration and upregulation of the heat-shock-mediated stress response. Moreover, we show that nuclear abnormalities represent a novel aspect of ALS pathogenesis as expression of DVAP-V260I either in neurons or muscles induces disruption in nuclear architecture, position and shape. Surprisingly, we found that transgenic expression of DVAP-V260I at the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ) induces an increase in the number of synaptic boutons and a decrease in their size. This phenotype is highly reminiscent of the phenotype associated with the neuronal overexpression of DVAP-WT protein and opposite to that of DVAP loss-of-function mutations and transgenic expression of the DVAP-P58S allele in neurons (Pennetta et al., 2002; Forrest et al., 2013). In addition, overexpression of DVAP-WT protein either in neurons or muscles induces phenotypes similar, albeit milder, than those associated with V260I expression. Altogether these data lead to the fundamental conclusion that DVAP-V260I is a pathogenic allele with an increased wild-type activity and that a combination of loss- and gain-of-function mechanisms are responsible for VAP-induced ALS. In conclusion, on the basis of the data reported here and those on previously identified mutations, we propose that VAPB levels or/and activity must be tightly regulated to keep neurons and muscles healthy as slight disturbances in one direction or the other may induce cell dysfunction and death.

Results

Presynaptic expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes leads to an overproduction of small synaptic boutons

The V234I mutation in the hVAPB gene recently identified in one ALS patient but not in a large number of healthy controls, is located within the conserved and functionally important transmembrane domain of VAP proteins (van Blitterswijk et al., 2012) (supplementary material Fig. S1). Conversely, the previously identified mutations, P56S and T46I, are localized in a highly conserved stretch of amino acids within the MSP domain (supplementary material Fig. S1C).

Presynaptic expression of the ALS-linked allele DVAP-P58S induces a NMJ phenotype characterized by a decrease in the number of boutons and an increase in their size (Chai et al., 2008; Ratnaparkhi et al., 2008). These data prompted us to examine the effect of DVAP-V260I expression on bouton formation and synaptic structure. We generated several transgenic lines expressing DVAP-V260I using the bipartite UAS/GAL4 system and the panneural elav-Gal4 as a driver (Lin and Goodman, 1994). To examine basic synaptic morphology, NMJs were stained with anti-HRP antibodies that label and allow for visualization of the entire presynaptic membrane. Changes in NMJ structure were assessed by counting the number of synaptic boutons at muscles 12 and 13 of the abdominal segment A3. This analysis revealed that transgenic expression of DVAP-V260I has clear consequences on the expansion of boutons as compared to controls. We were surprised to observe that, in this case, there is an increase in the total number of synaptic boutons when compared to controls (514±3 in elav;DVAP-V260I versus 272±2 in controls; P<0.001) (Fig. 1A,C). The size of boutons, however, is dramatically reduced.

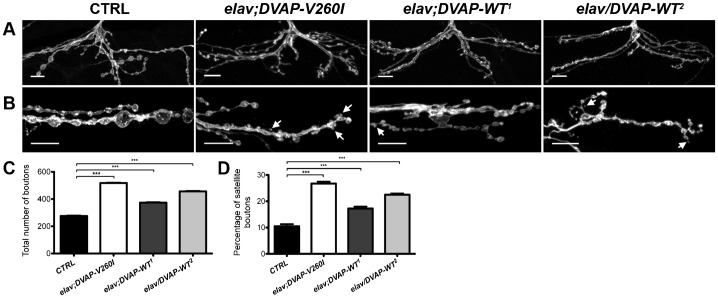

Fig. 1. Synaptic boutons are smaller, more numerous and clustered at NMJs expressing either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes.

(A) Representative images of muscle 12 NMJs from abdominal segment 3 labeled with an antibody against HRP. Scale bars: 10 µm. (B) Illustration of the synaptic overgrowth phenotype at HRP-stained NMJs of the indicated genotypes. In all panels arrows indicate satellite boutons. Scale bars: 10 µm. (C) Quantification of the total number of boutons at muscles 12 and 13 of abdominal segment 3 and (D) quantification of satellite boutons at muscles 6/7 of the abdominal segment 3 for each indicated genotype. elav-Gal4/+ NMJs were used as controls. Asterisks denote statistical significance compared to controls (***P<0.001).

We have previously shown that an increase in the number of boutons with a concomitant decrease in their size is associated with the presynaptic overexpression of DVAP-WT protein and that this phenotype is highly dependent on the dosage of the DVAP (Pennetta et al., 2002). To further confirm and extend this analysis, we generated a number of additional transgenic lines expressing different levels of the DVAP-WT protein and found that they all exhibited similar synaptic phenotypes. We selected a weak line (DVAP-WT1) in which the number of boutons on the muscles 12 and 13 of the segment A3 is 1.3-fold higher than in controls and a strong DVAP-WT2 line that exhibits a 1.7-fold increase in the number of synaptic boutons (Fig. 1A,C; P<0.001 in both cases).

We also noticed that in all transgenic lines the overall morphology of the synapse has changed. In control NMJs, synaptic boutons within a branch, resemble a string of beads with boutons connected to one another by a short neuritic process (Fig. 1B). In contrast, in larvae overexpressing either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes, many small boutons appear to bud off from a central bouton or from neuronal processes connecting two boutons (Fig. 1B, arrows). Clusters of smaller boutons surrounding central larger boutons are especially common in DVAP-V260I overexpressors (Fig. 1B,D). Boutons of similar size and morphology have been described in other overgrowth synaptic phenotypes and they have been called “satellite” boutons (Torroja et al., 1999; Franco et al., 2004; Kamimura et al., 2013). To correct for variations in total bouton number, we quantified the amount of “satellite” boutons for each genotype as a percentage of the mean total bouton number. We found that presynaptic expression of DVAP-V260I using the neuronal elav-Gal4 driver, induces a 2.6-fold increase in the percentage of “satellite” boutons compared to controls (Fig. 1B,D; P<0.001). Neuronal expression of either DVAP-WT1 or DVAP-WT2 transgenes using the same Gal4 driver, leads to 1.7-fold and 2.2-fold increase in satellite bouton number, respectively (Fig. 1B,D; P<0.001 in both cases). In summary, expression of either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes induces a dramatic change on the overall morphology of the synapse due, not only, to an increase in the total number of boutons but also to an elevated number of “satellite” boutons.

It was surprising to find an overgrowth synaptic phenotype associated with DVAP-V260I as transgenic expression of the previously identified DVAP-P58S allele in neurons leads to an opposite phenotype characterized by a decrease in the number of boutons and an increase in their size (Pennetta et al., 2002; Chai et al., 2008). The DVAP-P58S-induced phenotype is similar to that associated with DVAP loss-of-function mutations (Pennetta et al., 2002) leading to the hypothesis that DVAP-P58S is a loss-of-function allele (Pennetta et al., 2002; Ratnaparkhi et al., 2008; Chai et al., 2008). Accordingly, we found that in DVAP-P58S transgenics the endogenous wild-type protein accumulates in the aggregates distributed along the nerves and is depleted from its normal synaptic localization (supplementary material Fig. S2E, arrow). In particular, quantification of DVAP-positive staining at NMJs of DVAP-P58S expressing neurons results in nearly 45% decrease in the DVAP immunoreactivity compared to controls (supplementary material Fig. S2A,E,F; P<0.001). We then assessed the distribution and the local expression levels of DVAP at NMJs of both the DVAP-V260I and the two DVAP-WT lines. In agreement with the observed synaptic phenotypes, we found that elav-Gal4-driven expression of every transgene results in a rather homogenous distribution of DVAP at the synapse and quantification of DVAP-positive immunoreactivity revealed that in every case the amount of total protein is higher than in controls (supplementary material Fig. S2). Specifically, the increase in DVAP signal is 2.2-fold higher than in controls for the DVAP-WT2 line while it is 1.7-fold and 1.8-fold over the endogenous levels for DVAP-V260I and DVAP-WT1, respectively (supplementary material Fig. S2, P<0.001 in all cases). It is worth to note that although DVAP-WT1 and DVAP-V260I lines express comparable amounts of their respective transgenes, expression of the DVAP-WT1 transgene leads to synaptic phenotypes and indeed to a number of other phenotypes (see below) that are milder than those associated with the transgenic expression of the mutant allele (compare supplementary material Fig. S2 and Fig. 1). Furthermore, phenotypes induced by the expression of DVAP-V260I in eight tested lines are consistently more severe than those observed in a comparable number of lines expressing the DVAP-WT transgene (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that an increase in the levels of DVAP wild-type protein is sufficient to induce an overgrowth synaptic phenotype and that the DVAP-V260I mutant allele acts as a hypermorphic allele as it has an increased ability to promote bouton formation at the NMJ.

Presynaptic transgenic expression of DVAP-WT and DVAP-V260I leads to bouton expansion by affecting microtubule cytoskeleton architecture

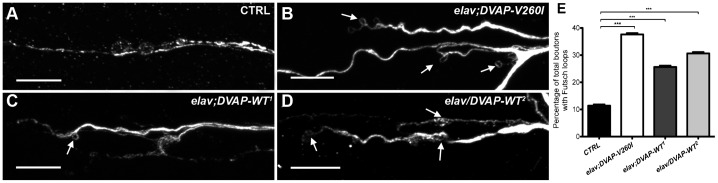

Formation of synaptic boutons at axon terminals is achieved via microtubules invading and promoting bouton budding from the plasma membrane (Roos et al., 2000). Within the Drosophila NMJ, excess of microtubule loop formation is associated with overgrowth phenotypes, particularly those with an increased number of “satellite” boutons (Franco et al., 2004; Kamimura et al., 2013). Thus, we asked whether the increase in bouton number in NMJs expressing either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes is related to alterations in microtubule cytoskeleton architecture. To address this question, we carried out immunostainings against the Drosophila MAP1B homologue Futsch, a marker of neuronal microtubule structures (Hummel et al., 2000; Roos et al., 2000).

DVAP-WT1, DVAP-WT2 and DVAP-V260I transgenes were each expressed in neurons using the elav-Gal4 driver and the number of Futsch-positive microtubule loops was quantified for every genotype. Presynaptic overexpression of DVAP-V260I shows a drastic increase in the number of Futsch-positive loops as compared to controls (38±0.4% versus 11±0.4% in controls, P<0.001) (Fig. 2A,B,E). A significant increase in the proportion of boutons containing a microtubule loop-like structure was also observed following the presynaptic expression of DVAP-WT transgenes (26±0.5% for DVAP-WT1 and 31±0.5% for DVAP-WT2). However, in both cases, the change is less than that associated with DVAP-V260I overexpressing mutants (Fig. 2C,D,E). Of note, an increase in number of boutons with more disorganized microtubule structure represented by splayed/punctuate Futsch-positive immunostaining was reported in larvae expressing DVAP-P58S and in DVAP loss-of-function mutants (Pennetta et al., 2002; Forrest et al., 2013). As expected, these NMJs exhibit an opposite synaptic phenotype characterized by a decrease in number of boutons and an increase in their size (Pennetta et al., 2002; Forrest et al., 2013). Thus, expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes in neurons, affects the organization of microtubule architecture, albeit at a different degree, with consequences on synaptic bouton formation and division.

Fig. 2. Expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes in neurons affects synaptic microtubule cytoskeleton.

(A) Representative images of branches of NMJs of third instar elav-Gal4/+ control larvae, (B) elav;DVAP-V260I, (C) elav;DVAP-WT1 and (D) elav/DVAP-WT2 larval NMJs labeled with antibodies against Futsch to show microtubule loops. Arrows in every panel indicate examples of Futsch loops. Scale bars: 10 µm. (E) Quantitative assessment of Futsch-positive loops at A2 and A3 muscle 4 NMJs for each indicated genotype. The highest increase in the percentage of boutons exhibiting looped Futsch staining (relative to the total number of boutons for each NMJ) was observed when DVAP-V260I was expressed presynaptically. Asterisks denote statistical significance compared to controls (***P<0.001).

Targeted expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes induces aggregate formation and nuclear abnormalities

DVAP is a ubiquitous protein and pathological alterations in muscles during ALS have been considered to result from toxicity of the mutant protein in motor neurons rather than a direct effect of the pathogenic protein on striated muscles. In order to explore whether the muscle is a direct target of DVAP-V260I and DVAP-WT toxicity, the expression of either the wild-type or mutant allele was selectively targeted to striated muscles, by using the muscle-specific driver BG57-Gal4 (Budnik et al., 1996).

Abnormal aggregates containing disease proteins are a common hallmark of several neurodegenerative disorders. We therefore stained dissected NMJs with DVAP antibodies to assess the localization of DVAP proteins in controls and in muscles expressing either the DVAP-WT or the DVAP-V260I transgenes. We found that while in controls DVAP is expressed throughout the muscle, in DVAP-V260I muscles numerous and punctuate, DVAP-immunopositive inclusions are present (Fig. 3A,B, Fig. 5A,B, staining in red). Interestingly, similar inclusions are also found in both the weak (DVAP-WT1) and strong (DVAP-WT2) transgenic lines overexpressing the DVAP-WT protein (Fig. 3C,D, Fig. 5C,D, staining in red). These data indicate that overexpression of the DVAP-WT protein is sufficient to induce the formation of aggregates and that DVAP-V260I is a pathogenic allele.

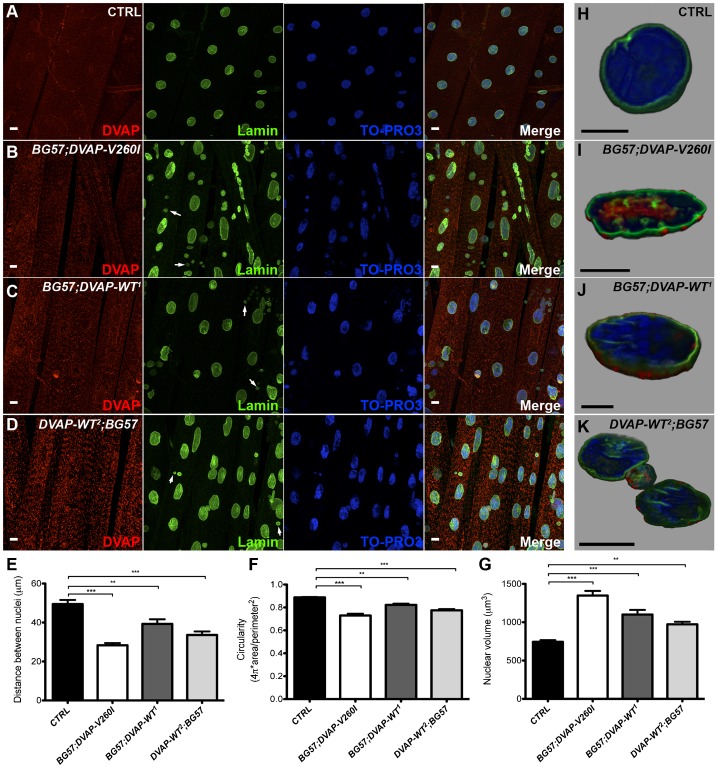

Fig. 3. Postsynaptic expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes results in aggregate formation and changes in nuclear shape, size and positioning.

(A) Third instar larval NMJs of BG57-Gal4/+ control, (B) BG57;DVAP-V260I, (C) BG57;DVAP-WT1 and (D) DVAP-WT2;BG57 NMJs expressing the indicated transgene in muscles were labeled with antibodies specific for DVAP and lamin. Nuclei were visualized with the nuclear specific marker TO-PRO3. (E) Quantification of the distance, (F) circularity and (G) volume of nuclei in randomly selected muscles for each indicated genotype. Sectioned volume renderings of representative triple-labelled nuclei of BG57-Gal4/+ controls (H); (I) BG57;DVAP-V260I; (J) BG57;DVAP-WT1 and DVAP-WT2;BG57 (K). Scale bars: 10 µm. Asterisks denote statistical significance. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01.

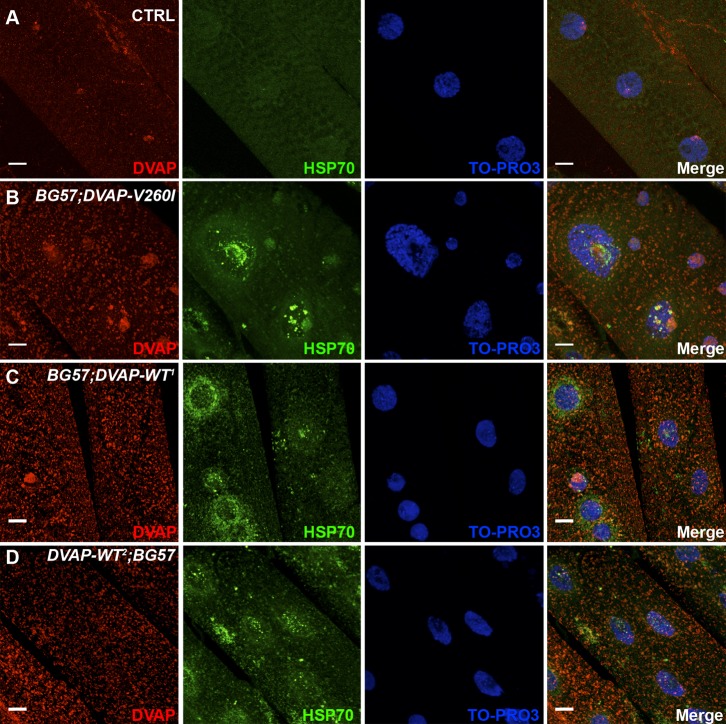

Fig. 5. Upregulation and subcellular relocalization of Hsp70 in striated muscles overexpressing either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT constructs.

(A) NMJs of BG57-Gal4/+ control larvae and (B) BG57;DVAP-V260I, (C) BG57;DVAP-WT1 and (D) DVAP-WT2;BG57 larvae expressing their respective transgene were immunolabeled with antibodies specific for DVAP and Hsp70 while nuclei were visualized with the TO-PRO3 nuclear marker. Scale bars: 10 µm. See text for comments.

Nuclear defects have been correlated with ageing as well as with a number of pathological manifestations in humans including Parkinson's disease (Worman et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012). To determine whether nuclear architecture or/and positioning are affected in our ALS fly model, we visualized nuclei in muscles overexpressing either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes using a nuclear marker and an anti-lamin antibody. We found that in controls, nuclei are evenly spaced along the muscle fibre while in muscles expressing either the DVAP-V260I or the DVAP-WT transgenes, nuclei are closely associated and exhibit a tendency to form clusters (Fig. 3). To better evaluate the relative position of nuclei within a muscle, a “nearest-neighbor” analysis was conducted for each genotype (see Materials and Methods for details). We found that, compared to controls, the average shortest distance between nuclei is severely reduced in muscles overexpressing the DVAP-V260I transgene (P<0.001) while the overexpression of the DVAP-WT transgenes has a significant but milder effect even in the case of the strongest DVAP-WT2 line (Fig. 3E; P<0.01 for DVAP-WT1 and P<0.001 for DVAP-WT2).

We also noticed a drastic deterioration in nuclear architecture. In particular, overexpression of either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes results in deformed nuclei with an elongated structure. To quantify this phenotype, we measured the width to length ratio of nuclei within muscles per each genotype. As the nuclei in control muscles have a distinct round shape, the width to length ratio is close to 1. Any deviation from this value indicates a loss of circularity and therefore a change in shape. We found that nuclei within muscles overexpressing the DVAP-V260I transgene are less round compared to nuclei in control muscles (Fig. 3A,B,F; P<0.001) and a similar, albeit milder effect, was observed in muscles overexpressing the DVAP-WT transgenes (Fig. 3A,C,D,F; P<0.01 for DVAP-WT1 and P<0.001 for DVAP-WT2). We also found that nuclei in muscles expressing the DVAP-V260I transgene display a marked enlarged nuclear volume compared to controls (Fig. 3G; P<0.001) as do the nuclei of muscles expressing the DVAP-WT transgenes, although to a lesser extent (Fig. 3G; P<0.001 for the DVAP-WT1 and P<0.01 for DVAP-WT2). Intriguingly, a fraction of DVAP protein that is predominantly a cytoplasmic protein was found to localize to the nucleus in DVAP-V260I overexpressing muscles while in both DVAP-WT lines this aberrant DVAP localization is nearly absent (Fig. 3H–K). A nuclear localization for DVAP has never been described before but previous studies have shown that translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus of α-synuclein associates with increased toxicity and neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease (Kontopoulos et al., 2006). Moreover, an increased number of small and condensed pyknotic nuclei was predominantly observed in muscles overexpressing the DVAP-V260I transgene while such nuclei are significantly less in the weak DVAP-WT1 line (Fig. 3, white arrows).

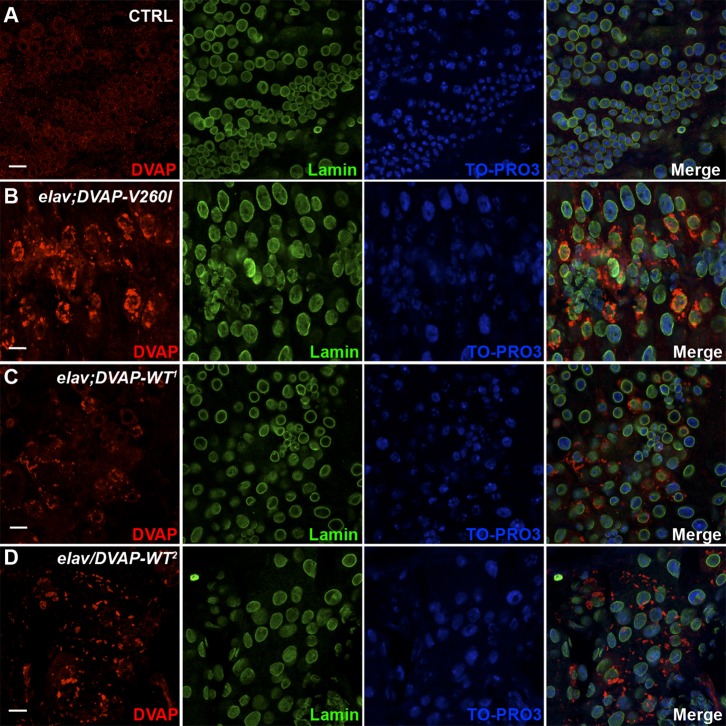

Finally, we noticed that larger and malformed nuclei are also observed in neurons of larval brains expressing either the DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes and again the phenotype appears to be more severe when the mutant transgene is expressed (Fig. 4). In addition, expression of DVAP-V260I in neurons also induces accumulation of prominent inclusions that appear to be very large and intensely immunoreactive to DVAP antibodies (Fig. 4A,B). In contrast, in neurons of the weakest DVAP line (DVAP-WT1), small and isolated foci accumulating DVAP were observed. Although not directly quantified, the number of these foci appear to be increased in neurons of the strongest DVAP-WT2 line (Fig. 4C,D). Interestingly, no small pyknotic nuclei were observed in these neurons that present an aberrant nuclear architecture.

Fig. 4. Expression of DVAP-V260I and DVAP-WT transgenes in neurons leads to aggregate accumulation and disruption of nuclear architecture.

(A) Brains of elav-Gal4/+ control larvae and (B) elav;DVAP-V260I, (C) elav;DVAP-WT1, (D) elav/DVAP-WT2 larval brains expressing their respective transgene in neurons were immunostained with antibodies specific for DVAP and Lamin. Nuclei were labeled with the nuclear marker TO-PRO3. Scale bars: 10 µm.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that transgenic expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT in neurons as well as in muscles elicits the formation of aggregates and a severe disruption in the architecture, size and positioning of nuclei.

Induction of the heat-shock response in DVAP-WT and DVAP-V260I overexpressors

In many neurodegenerative diseases including ALS, aggregates are thought to be formed from the accumulation of misfolded proteins that trigger the upregulation of chaperone proteins (Vabulas et al., 2010). We assessed whether this was also the case for larvae expressing either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes in their muscles. In controls, Hsp70 is barely detectable and results in faint and diffuse staining throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). In transgenic animals expressing the DVAP-V260I construct specifically in the striated muscles, there is an increase in the expression levels of Hsp70 that appears to concentrate in puncta mainly localized inside the nucleus (Fig. 5B). In transgenic muscles expressing the DVAP-WT transgenes, an increase in the accumulation of puncta immunoreactive to the Hsp70 was observed. These puncta are partially localized into the nucleus in muscles expressing the strongest wild-type transgene DVAP-WT2 (Fig. 5D). Conversely, in muscles expressing the weak DVAP-WT1 transgene, puncta are still present in the cytoplasm, although the majority of them preferentially accumulate in the perinuclear region (Fig. 5C). The phenomenon of the Hsp70 relocating from the cytoplasm to the nucleus during a stress response is poorly understood; however, it is clear that this relocation is directly linked and is part of the cellular response to stress (Vabulas et al., 2010). Taken together, these data indicate that in DVAP-V260I as well as in DVAP-WT overexpressors, a stress response mediated by heat-shock proteins has been induced and that the intensity of this response directly correlates with the toxicity of the overexpressed protein.

Expression of DVAP-V260I and DVAP-WT in adult flies induces reduced viability, compromised locomotion behavior and neuromuscular defects

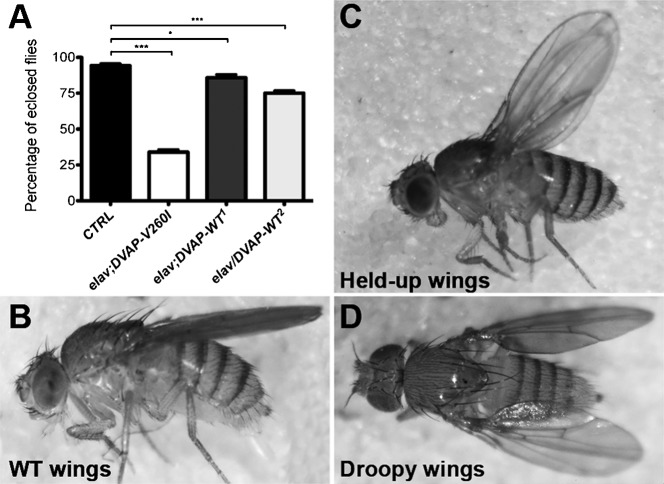

We showed that expression of DVAP-V260I and DVAP-WT transgenes in larval neurons and muscles causes a number of phenotypes closely mirroring the human pathology. We then sought to test whether the same transgenes have any effect on the adult neuromuscular junctions. We first expressed the DVAP-V260I or the DVAP-WT transgenes in the adult nervous system by using the panneural driver elav-Gal4. Flies expressing either the DVAP-V260I transgene or any of the two wild-type transgenic construct, are able to pupate and adults eclose from pupae. However, the rate of eclosion is different depending on the overexpressed transgene (Fig. 6A). Flies expressing the DVAP-WT1 transgene have a small but statistically significant decrease in the rate of eclosion (Fig. 6A; P<0.05) while for flies expressing the strongest wild-type allele, DVAP-WT2, the rate of eclosion is 75% (Fig. 6A; P<0.001). A strong reduction in the number of flies eclosed as viable adults is observed when the expression of the DVAP-V260I was targeted in the adult neurons. In this case only 35% of pupae eclose to give an adult fly (Fig. 6A). However, all flies, irrespective of their genotypes, display distinctive postural and locomotion defects as viable adults. While in controls, wings run dorsal and parallel to the body, surviving mutants exhibit different wing posture phenotypes including droopy and held-up wings (Fig. 6B–D). Additionally, surviving adult flies are severely uncoordinated and within a few days following eclosion, get stuck to the food and die. When the expression of either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I constructs is targeted to all muscles by using the MHC-Gal4 driver, the progeny exhibits the same wing posture phenotypes as for the neuronal expression of the same transgenes but their eclosion ratio is similar for every transgene and closer to that of controls (supplementary material Fig. S3). Similar adult phenotypes have been described in a number of fly models of human neurodegenerative diseases including Fragile X syndrome and Parkinson's disease and have been attributed to neuromuscular dysfunction (Zhang et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2006).

Fig. 6. DVAP-V260I and DVAP-WT overexpressors display reduced viability and wing postural defects.

(A) Eclosion rate of flies of the designated genotype. (B) elav-Gal4/+ control flies with a dorsal wing posture. (C) Held-up wings and (D) droopy wing flies. See text for comments. Asterisks denote statistical significance. ***P<0.001, *P<0.05.

Targeted expression of either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes in the adult Drosophila eye causes neuronal degeneration

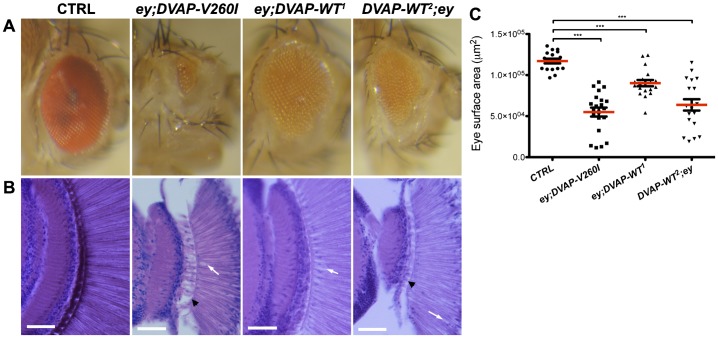

Neuronal degeneration in Drosophila models of human neurodegenerative disorders including ALS is usually assessed in the adult fly eye. To determine whether overexpression of DVAP-WT protein and transgenic expression of DVAP-V260I causes neurodegeneration, we used the ey-Gal4 driver to specifically target the expression of these transgenes in the adult fly eye (Halder et al., 1998; Hauck et al., 1999). Adult fly eyes expressing either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes display a range of structural abnormalities. As compared with controls, eyes expressing either the DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes are reduced in size and show a marked roughness over the entire surface (Fig. 7A). A striking aspect of the eye phenotype induced by the overexpression of either DVAP-WT or the DVAP-V260I transgenes, is the high degree of heterogeneity in the severity of the phenotype within the same line and even within the same fly as, in many cases, one of the eyes exhibits a more extensive degeneration than the eye on the opposite side. We therefore quantified the phenotype in both control and overexpressor lines by measuring the eye size in a comparable number of flies for every genotype. Overall, the eye size of DVAP-V260I transgenic flies is less than 50% of the control size while the measured reduction in eye size for DVAP-WT1 and DVAP-WT2 was 30% and 20%, respectively (Fig. 7C; P<0.001 in all cases).

Fig. 7. Expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes in adult Drosophila eyes induce neurodegeneration.

(A) Stereomicroscope images of ey-Gal4/+ control eyes and eyes of the indicated genotypes. (B) Frontal sections of control and transgenic eyes of the indicated genotypes stained with H&E. White arrows point to vacuoles in photoreceptors while the black arrowheads indicate areas of extensive tissue degeneration. (C) Quantification of the eye surface area of every genotype. Scale bars: 50 µm. Asterisks denote statistical significance (***P<0.001).

Histopathological analysis of paraffin embedded sections of transgenic eyes expressing either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I confirmed the degeneration of cells beneath the external surface of the eye (Fig. 7B). In particular, photoreceptor morphology is disrupted and several vacuoles are visible. Vacuolization has been observed in a number of fly models of neurodegenerative diseases and the appearance of vacuoles has been correlated to neurodegeneration (Chan and Bonini, 2000). Of note, the strongest phenotype for both the reduction in the eye size and the degeneration of the internal eye is that associated with the expression of the DVAP-V260I transgene (Fig. 7). The internal tissues of transgenic eyes expressing the DVAP-WT protein are disrupted in a similar way, albeit to a lesser extent, especially when the weakest line DVAP-WT1 is considered (Fig. 7B). In conclusion, these data indicate that increasing the level of expression of the DVAP-WT protein is sufficient to trigger neurodegeneration, although transgenic expression of the mutant DVAP-V260I allele appears to be more efficient in inducing neuronal cell death.

Discussion

Recently, a novel mutation in the gene hVAPB has been identified in one ALS patient who is also known to have a pathogenic repeat expansion in the C9ORF72 gene. The missense mutation replaces the Valine with an Isoleucine at codon 234, a highly conserved residue within the C-terminal transmembrane domain of VAP proteins (van Blitterswijk et al., 2012). In Drosophila, the transmembrane domain of DVAP binds the phosphoinositide phosphatase Sac1 to control phosphoinositide levels whose upregulation is responsible for neurodegeneration and a number of synaptic phenotypes including altered synaptic morphology and mislocalization of several post-synaptic markers (Forrest et al., 2013). Moreover, in mammals the transmembrane-mediated interaction of VAPB with the ER–Golgi recycling protein YIF1A controls dendritic remodeling in the central nervous system (Kuijpers et al., 2013a). It is therefore plausible that mutations targeting this important functional domain may have a pathogenic effect.

Here we report that transgenic expression of DVAP-V260I in Drosophila, induces mutant phenotypes that closely mirror major hallmarks of ALS such as structural remodeling at NMJs, formation of aggregates, abnormal locomotion behavior, reduced viability, neuromuscular defects and upregulation of the heat-shock-mediated stress response. In addition, muscles and neurons expressing the DVAP-V260I transgene exhibit striking abnormalities in nuclear positioning, shape and size. Interestingly, nuclear abnormalities have never been linked to ALS pathogenesis.

Previously identified disease mutations in hVAPB are loss-of-function mutations, possibly by a dominant negative mechanism (Ratnaparkhi et al., 2008; Forrest et al., 2013; Kuijpers et al., 2013a). We were therefore surprised to find that transgenic expression of DVAP-V260I construct consistently produces similar but more severe phenotypes than those associated with the overexpression of the wild-type protein. Collectively, our results show that a gain-of-function mechanism is responsible for VAPB-induced ALS and that the V234I is a pathogenic allele with an increased wild-type activity. In conclusion, we propose that both gain- and loss-of-function effects play an important role in driving the damage, which ultimately leads to cellular downfall and clinical expression of the disease.

Nuclear abnormalities in ALS pathogenesis

Mispositioning of nuclei has been associated with decreased cell survival in vertebrate central nervous system (Tsujikawa et al., 2007). In striated muscles, myonuclei appear as rounded structures evenly spaced along muscle fibers separated from the bulk of the cytoplasm, which contains densely arranged myofibrils. The mechanisms establishing and maintaining this highly ordered distribution of nuclei and its relevance to muscle function is not known but several human myopathies are caused by mutations in genes such as Nesprins that control the correct position and distribution of nuclei in muscles (Puckelwartz et al., 2010). Furthermore, Nesprin-1 knockout mice exhibit 50% lethality and those surviving display progressive muscle wasting and abnormal gait (Puckelwartz et al., 2009). Nuclear architecture defects have been shown to correlate with aging as well as with a number of human diseases, including Parkinson's disease (Liu et al., 2012).

To study the role that nuclear position and structure might have in ALS, we targeted the expression of DVAP-WT and DVAP-V260I in neurons and muscles. Our morphometric analysis revealed that overexpression of the DVAP-V260I results in deformed nuclei with an elongated structure and a marked enlarged nuclear volume. We also found that in DVAP-V260I transgenic muscles the average distance between nuclei is remarkably reduced and sometimes, nuclei are found to aggregate into clusters. A similar deterioration in nuclear architecture and positioning was observed in muscles overexpressing DVAP-WT transgenes but, overall, the defects are milder than those associated with the expression of DVAP-V260I even when the strongest DVAP-WT2 transgene is expressed. In summary, nuclear abnormalities are more prominent in transgenic conditions associated with a more aggressive disease phenotype.

Finally, small and condensed pyknotic nuclei were observed in muscles expressing DVAP-V260I and to a lesser extent in those overexpressing the DVAP-WT transgene. Although the presence of pyknotic nuclei is a hallmark of apoptosis, we do not believe that the observed nuclear abnormalities are a mere consequence of apoptotic cell death. No condensed, pyknotic nuclei are present in neurons expressing any DVAP-WT transgenes or DVAP-V260I protein at the time when nuclear abnormalities are already visible. These results suggest that defects in nuclear architecture and distribution may precede the appearance of apoptotic hallmarks. Indeed recent studies suggest that alterations in nuclear structure and positioning represent an irreversible trigger of apoptosis rather than a consequence of this process (Liu et al., 2012).

Taken together, these studies identify the nucleus as a novel cellular organelle involved in ALS pathogenesis and open new avenues for the potential development of therapies targeting this fundamental cellular structure.

Expression of either DVAP-V260I or DVAP-WT transgenes recapitulates major ALS-related hallmarks

The data discussed in the previous paragraph suggest that our DVAP-V260I fly model may function as a platform for the discovery and study of novel and, at the moment, elusive aspects of ALS pathogenesis. Our data also suggest that this model recapitulates many of the phenotypes known to be associated with ALS and indeed with a number of other neurodegenerative diseases.

In Drosophila, DVAP interacts with the adhesion molecule Dscam to affect synaptic connectivity and its homologue in mammals, VAPB, is required for intracellular membrane trafficking and normal dendritic growth (Yang et al., 2012; Kuijpers et al., 2013a). In addition, loss-of-function mutations in the SMN (Survival motor neuron) gene, the causative gene of the motor neurone disease spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), induces defects in axons and synaptic structure (Torres-Benito et al., 2012). Similar results have been reported for the ALS-linked gene VCP (Valosin Containing Protein) as mutations in this gene lead to impaired synaptogenesis and spinogenesis (Wang et al., 2011). To study the effect of DVAP-WT and mutant DVAP-V260I transgenes on synaptic remodeling and structure, we focused on the Drosophila larval NMJ. Morphological analysis shows that at NMJs overexpressing either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I transgenes, boutons are smaller, more numerous and tend to form dense clusters especially at the ends of terminal branches. Overgrowth synaptic phenotypes have been associated with alterations in microtubule networks and specifically with an increase in the percentage of boutons containing microtubule loop-like structures (Torroja et al., 1999). Indeed we found that at NMJs expressing DVAP-V260I there is a specific increase in this category of boutons. Similar, but less severe, phenotypes are associated with the transgenic expression of the DVAP-WT protein. In contrast, expression of the ALS-linked allele DVAP-P58S in neurons and loss-of-function mutations in DVAP induce a reduction in number of boutons and an increase in their size. A shift in microtubule structures towards less organized morphologies, which is often associated with undergrowth synaptic phenotypes, was also observed in this transgenic condition (Pennetta et al., 2002). In agreement with these data, we show that there is a local increase in DVAP levels at DVAP-V260I expressing NMJs and a decrease in synapses expressing DVAP-P58S. In summary, we propose that disruption of synaptic remodeling and structure may represent a fundamental and common aspect of disease pathogenesis in ALS and that the DVAP-V260I allele, in contrast to the DVAP-P58S allele, exhibits an increased wild-type activity.

A common feature of neurodegenerative diseases is the presence of misfolded protein aggregates in affected regions of the nervous system. Many neurodegenerative proteins behave like prion proteins (Polymenidou and Cleveland, 2012). In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that these proteins exhibit a high tendency to self-aggregate because of their intrinsic ability to undergo a series of kinetically unfavorable conformational changes to produce misfolded proteins. Increasing the concentration of the native protein favors the formation of aggregates and disease-linked mutations often appear to confer to the protein an increased ability to generate inclusions (Eisele, 2013). Further studies are necessary to assess whether DVAP is a prion-like protein. However, as expected for a prion-like protein, DVAP-WT overexpression is sufficient to induce the formation of aggregates in a dosage-dependent manner and transgenic expression of the mutant DVAP-V260I protein effectively leads to the accumulation of large protein inclusions even at relatively low doses.

In our Drosophila model, muscles expressing the DVAP-V260I transgene, which associates with the most aggressive disease phenotype, exhibit a relocalization of DVAP protein into the nucleus. DVAP remains predominantly localized to the cytoplasm in controls and in all the other transgenic conditions exhibiting a milder disease phenotype. The mechanism by which DVAP enters the nucleus is unclear; however, this relocalization closely resembles the relocalization from the cytoplasm to the nucleus reported for α-synuclein, a protein involved in Parkinson's disease (PD). Normal and PD-linked α-synucleins promote toxicity by relocating to the nucleus where they bind to histones and inhibit their acetylation. Administration of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors restores the histone acetylation state and rescues α-synuclein-mediated toxicity (Kontopoulos et al., 2006). Remarkably, administration of HDAC inhibitors to ALS mouse models successfully decreases cell toxicity (Yoo and Ko, 2011).

Implications for ALS pathogenesis

Loss or depletion of VAPB activity in zebrafish, worms and mice induce a relatively mild phenotype possibly because of a functional redundancy between closely related VAP proteins in these models (Kabashi et al., 2013; Han et al., 2012). In Drosophila, only one VAP gene is present and therefore its inactivation leads to the appearance of a more aggressive mutant phenotype (Pennetta et al., 2002; Forrest et al., 2013). Mice expressing the VAPB-P56S transgene have been generated and they exhibit no overt neurodegenerative phenotype (Aliaga et al., 2013; Qiu et al., 2013; Tudor et al., 2010; Kuijpers et al., 2013b). However, a recent report describes degeneration of a subset of motor neurons in mice expressing higher levels of the VAPB-P56S transgene (Aliaga et al., 2013). In addition, neurodegeneration has been associated with the expression of the same transgene in cell culture systems (Langou et al., 2010; Suzuki and Matsuoka, 2011; Teuling et al., 2007). Taken together these considerations further underscore the importance of VAPB dosage in inducing ALS-like phenotypes, including neurodegeneration. It is not uncommon that genetic models fail to reproduce the full range of clinical manifestations associated with a human disease and for this non-human primate models should represent a better option. Genetic models, however, remain invaluable tools to dissect mechanistic aspects of disease pathogenesis.

Studies in several model systems showed that the P56S mutation induces ALS by a loss-of-function mechanism, possibly due to a dominant negative effect (Ratnaparkhi et al., 2008; Tsuda et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2009; Forrest et al., 2013; Kuijpers et al., 2013a). Furthermore, a reduction in VAP protein levels have been reported in sporadic ALS patients, SOD1 mutant mice as well as in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from ALS patients (Teuling et al., 2007; Anagnostou et al., 2010; Mitne-Neto et al., 2011). The dominant negative effect of P56S mutation is further supported by the observation that the mutant protein accumulates into intracellular inclusions, which also sequester the wild-type protein (Teuling et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010). Here we uncover a novel mechanism for the disease pathogenesis and we show that increasing the levels and/or activity of DVAP may be detrimental as well. The notion that increased hVAPB levels are sufficient to induce neurodegeneration would be greatly supported by finding that duplications or mutations in the non-coding regions of the hVAPB gene are associated with ALS in humans. For hVAPB, however, such mutations have yet to be identified. These and other studies indicate that, in many cases, a strict dichotomy between loss-of-function versus gain-of-function mechanisms do not respond to a biological reality as both mechanisms seem to be at play (Robberecht and Philips, 2013). In support of this hypothesis, variations in the dosage of the SMN gene have been shown to induce two closely related motor neuron diseases as loss-of-function mutations in SMN cause Spinal Muscular Atrophy while duplications of the same gene have been linked to ALS (Bürglen et al., 1995; Blauw et al., 2012).

Finally, our data are compatible with a model in which, in DVAP-V260I-induced ALS, gain- and loss-of-function mechanisms may coexist within the same neuron depending on the subcellular compartment. At the presynaptic compartment, a local increase in DVAP levels induces a remodeling of synaptic morphology and microtubule architecture compatible with a gain-of-function mechanism. Conversely, in neuronal cell bodies the inherent ability of wild-type hVAPB to be included into aggregates that may also function as a sink for other important proteins, suggests that DVAP could be pathogenic by a possible loss-of-function mechanism. The complexity of such a scenario pinpoints to novel opportunities for possible therapies but at the same time makes the task of finding an effective therapeutic strategy particularly challenging.

Materials and Methods

Fly strains and husbandry

Flies were reared in standard cornmeal–molasses medium and maintained at room temperature unless otherwise specified. To drive the expression of DVAP transgenes in neurons, larval muscles and adult eyes we used the elav-Gal4 line (Lin and Goodman, 1994), the BG57-Gal4 line (Budnik et al., 1996) and the ey-Gal4 line (Halder et al., 1998; Hauck et al., 1999), respectively. We used the ey-Gal4 instead of the GMR-Gal4 driver because GMR-GAL4 has been shown to induce eye neurodegeneration on its own (Rezával et al., 2007). Transgenic expression in adult muscles was achieved by using the MHC-Gal4 line.

Generation of DVAP-WT and DVAP-V260I transgenic lines

Site-directed mutagenesis on DVAP cDNA was performed using the Quick Change Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) following manufacturer's instructions. Gal4-resposive transgenic lines were constructed cloning DVAP-WT and DVAP-V260I cDNAs in the pUAST vector (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) using the cloning strategy previously described (Pennetta et al., 2002). Constructs were injected into embryonic germ cells and transgenic lines were established following standard procedures (Genetic Services, Inc., Sudbury, MA, USA). Given the strong dosage-dependent effect on mutant phenotypes observed for both the DVAP-WT and V260I transgenes, in generating the transgenic lines we opted for the method of random transgene insertion instead of that in which transgenes are inserted at specific sites (Bischof et al., 2007). Using this approach, we generated 8 independent transgenic lines expressing different levels of either DVAP-WT or DVAP-V260I proteins.

Genetics

For temperature pulses, to induce a higher expression of the Gal4 protein, flies of the relevant genotypes were left to mate at room temperature for 20–24 hours and then the parents were removed while the progeny was shifted to 30°C in a water bath. Only for the ey-GAL4 experiments, crosses and rearing of animals were performed at 25°C because at higher temperatures adult flies fail to eclose, possibly due to an ectopic, toxic expression of the transgene in areas of the nervous system other than the eye.

Immunohistochemistry

To study NMJ morphology, wandering third instar larvae were dissected and processed as previously described (Pennetta et al., 2002). Control genotypes used for analysis were F1 larvae from Canton-S males crossed to the homozygous females of the relevant GAL4 driver line. Primary antibodies are rabbit anti-HRP antibodies (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), mouse anti-Futsch 22C10 monoclonal antibody (1:200, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, USA), rabbit anti-Lamin antibody (1: 500), guinea pig anti-DVAP antibody (1:500, Pennetta et al., 2002) and mouse anti-Hsp70 (1:200, Affinity Bioreagents, Rockford, IL, USA). Secondary antibodies were used at a 1:200 dilution.

Confocal analysis and imaging

Confocal z-stacks were acquired on a Nikon A1R (Nikon, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, UK) using an ×60/1.4 NA oil immersion plan-apochromat with a sampling rate of 0.4×0.4×0.27 µm in x, y and z, respectively. For multicolour images a channel series protocol was used to minimize bleed through. The same confocal gain settings were applied to control and transgenic samples. Images were processed using Imaris v 7.3.0 (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland). For z-stacks, iso-surfaces were created in surpass mode for both lamin and TO-PRO3; whole nuclei were selected from the 3D image volume and measurements for volume, and object bounding box size were acquired. Imaris measurement-pro was used to measure the distances between nuclei along each muscle fibre. To measure the circularity of nuclei within muscles, images were analyzed with ImageJ software (ImageJ software, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Circularity is defined as 4π×Area/Perimeter2, where 1 represents a perfect circle and 0 an infinitely elongated polygon. For visualization of DVAP within the nucleus a 3D-volume view of DVAP and TO-PRO3 was combined with an iso-surface of the lamin and a contour plane was used to cut into the lamin volume and show the localization of DVAP within the nucleus.

NMJ morphological analysis

To quantify the overgrowth phenotypes at the NMJ, body wall muscle preparations were labeled with the presynaptic marker anti-HRP and two different parameters were measured. The total number of synaptic boutons was counted at muscles 12 and 13 of abdominal segment A3 and the percentage of satellite boutons (satellite×100/total boutons) on muscles 6 and 7 of the abdominal segment A3 was also determined. Satellite boutons at the NMJs were defined, identified and quantified according to Torroja et al. (Torroja et al., 1999). The number of loop containing boutons was counted on muscles 4 of the abdominal segments A2 and A3 and expressed as a percentage of the total number of boutons for each NMJ.

Quantification of the distance between myonuclei

A nearest-neighbor analysis was performed to quantify the distance between nuclei along a given myofibre. A nearest-neighbor analysis determines the average distance between a nucleus and its single closest neighbor within a muscle. To identify the closest neighbor for each nucleus within a muscle, the distance between the center of a nucleus and the center of each closely surrounding nucleus was measured. Only the shortest distance between a nucleus and its nearest neighbor was recorded per each nucleus within a muscle and the average of these distances was taken as a measure of the shortest distance between nuclei in a given muscle.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis including graphing was performed using GraphPad 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, LaJolla, CA, USA). For all the experiments, a one-way ANOVA test was applied to the samples. Tukey's multiple comparison tests were used as a post-hoc test when a significant difference was found in the ANOVA test. Data throughout the paper are presented as mean ± s.e.m. A minimum of 10 larvae were analyzed per every genotype. At least 20 flies per genotype were analyzed in scoring the adult eye phenotype.

Analysis and quantification of the Drosophila adult eye phenotype

For the eye morphology, two-dimensional images were obtained using a Nikon D5100 DSLR camera attached to a SZX9 Nikon stereomicroscope (Nikon, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, UK). To quantify the eye surface area images were analyzed with ImageJ software. For histology, flies were raised at 25°C and collected immediately after eclosion. Heads were severed and place in fresh fixative (ethanol:formaldehyde:acetic acid at 85:10:5) overnight at 4°C. Heads were then washed and placed in 70% ethanol and processed into paraffin using standard histological procedures. 10 µm serial sections were obtained and rehydrated with PBS. Sections were stained with H&E.

Adult phenotypes

Eclosion rates were determined by counting numbers of empty versus full (dead) pupae on the sides of vials in which flies of different genotypes had been allowed to lay for comparable time periods. Food was covered with a thick layer of yeast powder to avoid that eclosed flies with an aberrant wing posture would get stuck to the food. Flies exhibiting an aberrant posture in their wings were collected and their phenotype was recorded using an Olympus ZEX stereomicroscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) equipped with a Nikon D5100 DSLR camera.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for monoclonal antibodies; Bing Zhang and Hermann Haberle for fly stocks; Paul Fisher for the polyclonal lamin antibody.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: L.Z., M.S. and G.P. performed the experiments; M.S., T.G. and G.P. analyzed data; G.P. conceived and designed the experiments, and wrote the paper.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [grant number: Pennetta8920] and by the Motor Neuron Disease Association [grant number: Pennetta6231].

References

- Aliaga L., Lai C., Yu J., Chub N., Shim H., Sun L., Xie C., Yang W. J., Lin X., O'Donovan M. J. et al. (2013). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-related VAPB P56S mutation differentially affects the function and survival of corticospinal and spinal motor neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 4293–4305 10.1093/hmg/ddt279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarilio R., Ramachandran S., Sabanay H., Lev S. (2005). Differential regulation of endoplasmic reticulum structure through VAP-Nir protein interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5934–5944 10.1074/jbc.M409566200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou G., Akbar M. T., Paul P., Angelinetta C., Steiner T. J., de Belleroche J. (2010). Vesicle associated membrane protein B (VAPB) is decreased in ALS spinal cord. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 969–985 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K. (2007). An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3312–3317 10.1073/pnas.0611511104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauw H. M., Barnes C. P., van Vught P. W., van Rheenen W., Verheul M., Cuppen E., Veldink J. H., van den Berg L. H. (2012). SMN1 gene duplications are associated with sporadic ALS. Neurology 78, 776–780 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318249f697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H., Perrimon N. (1993). Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnik V., Koh Y. H., Guan B., Hartmann B., Hough C., Woods D., Gorczyca M. (1996). Regulation of synapse structure and function by the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg. Neuron 17, 627–640 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80196-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürglen L., Spiegel R., Ignatius J., Cobben J. M., Landrieu P., Lefebvre S., Munnich A., Melki J. (1995). SMN gene deletion in variant of infantile spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet 346, 316–317 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92206-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai A., Withers J., Koh Y. H., Parry K., Bao H., Zhang B., Budnik V., Pennetta G. (2008). hVAPB, the causative gene of a heterogeneous group of motor neuron diseases in humans, is functionally interchangeable with its Drosophila homologue DVAP-33A at the neuromuscular junction. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 266–280 10.1093/hmg/ddm303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. Y., Bonini N. M. (2000). Drosophila models of human neurodegenerative disease. Cell Death Differ. 7, 1075–1080 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. J., Anagnostou G., Chai A., Withers J., Morris A., Adhikaree J., Pennetta G., de Belleroche J. S. (2010). Characterization of the properties of a novel mutation in VAPB in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40266–40281 10.1074/jbc.M110.161398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I. E., Dodson M. W., Jiang C., Cao J. H., Huh J. R., Seol J. H., Yoo S. J., Hay B. A., Guo M. (2006). Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature 441, 1162–1166 10.1038/nature04779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele Y. S. (2013). From soluble aβ to progressive aβ aggregation: could prion-like templated misfolding play a role? Brain Pathol. 23, 333–341 10.1111/bpa.12049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest S., Chai A., Sanhueza M., Marescotti M., Parry K., Georgiev A., Sahota V., Mendez-Castro R., Pennetta G. (2013). Increased levels of phosphoinositides cause neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 2689–2704 10.1093/hmg/ddt118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco B., Bogdanik L., Bobinnec Y., Debec A., Bockaert J., Parmentier M. L., Grau Y. (2004). Shaggy, the homolog of glycogen synthase kinase 3, controls neuromuscular junction growth in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 24, 6573–6577 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1580-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke A. D., Esser M., Krüttgen A., Weis J., Mitne-Neto M., Lazar M., Nishimura A. L., Sperfeld A. D., Trillenberg P., Senderek J. et al. (2010). The p.P56S mutation in the VAPB gene is not due to a single founder: the first European case. Clin. Genet. 77, 302–303 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01319.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkogkas C., Middleton S., Kremer A. M., Wardrope C., Hannah M., Gillingwater T. H., Skehel P. (2008). VAPB interacts with and modulates the activity of ATF6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 1517–1526 10.1093/hmg/ddn040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G., Callaerts P., Flister S., Walldorf U., Kloter U., Gehring W. J. (1998). Eyeless initiates the expression of both sine oculis and eyes absent during Drosophila compound eye development. Development 125, 2181–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S. M., Tsuda H., Yang Y., Vibbert J., Cottee P., Lee S.-J., Winek J., Haueter C., Bellen H. J., Miller M. A. (2012). Secreted VAPB/ALS8 major sperm protein domains modulate mitochondrial localization and morphology via growth cone guidance receptors. Dev. Cell 22, 348–362 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck B., Gehring W. J., Walldorf U. (1999). Functional analysis of an eye specific enhancer of the eyeless gene in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 564–569 10.1073/pnas.96.2.564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T., Krukkert K., Roos J., Davis G., Klämbt C. (2000). Drosophila Futsch/22C10 is a MAP1B-like protein required for dendritic and axonal development. Neuron 26, 357–370 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81169-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingre C., Pinto S., Birve A., Press R., Danielsson O., de Carvalho M., Guđmundsson G., Andersen P. M. (2013). No association between VAPB mutations and familial or sporadic ALS in Sweden, Portugal and Iceland. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 14, 620–627 10.3109/21678421.2013.822515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi E., El Oussini H., Bercier V., Gros-Louis F., Valdmanis P. N., McDearmid J., Mejier I. A., Dion P. A., Dupre N., Hollinger D. et al. (2013). Investigating the contribution of VAPB/ALS8 loss of function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 2350–2360 10.1093/hmg/ddt080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S. E., Brickner J. H., Reilein A. R., Fenn T. D., Walter P., Brunger A. T. (2005). Structural basis of FFAT motif-mediated ER targeting. Structure 13, 1035–1045 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura K., Ueno K., Nakagawa J., Hamada R., Saitoe M., Maeda N. (2013). Perlecan regulates bidirectional Wnt signaling at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Cell Biol. 200, 219–233 10.1083/jcb.201207036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekura K., Nishimoto I., Aiso S., Matsuoka M. (2006). Characterization of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked P56S mutation of vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB/ALS8). J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30223–30233 10.1074/jbc.M605049200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontopoulos E., Parvin J. D., Feany M. B. (2006). α-synuclein acts in the nucleus to inhibit histone acetylation and promote neurotoxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 3012–3023 10.1093/hmg/ddl243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers M., Yu K. L., Teuling E., Akhmanova A., Jaarsma D., Hoogenraad C. C. (2013a). The ALS8 protein VAPB interacts with the ER-Golgi recycling protein YIF1A and regulates membrane delivery into dendrites. EMBO J. 32, 2056–2072 10.1038/emboj.2013.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers M., van Dis V., Haasdijk E. D., Harterink M., Vocking K., Post J. A., Scheper W., Hoogenraad C. C., Jaarsma D. (2013b). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-associated VAPB-P56S inclusions represent an ER quality control compartment. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 1, 24 10.1186/2051-5960-1-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers J. E., Leclerc A. L., Shi L., Virkud A., Cho T., Maxwell M. M., Henry A. F., Polak M., Glass J. D., Kwiatkowski T. J. et al. (2008). New VAPB deletion variant and exclusion of VAPB mutations in familial ALS. Neurology 70, 1179–1185 10.1212/01.wnl.0000289760.85237.4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langou K., Moumen A., Pellegrino C., Aebischer J., Medina I., Aebischer P., Raoul C. (2010). AAV-mediated expression of wild-type and ALS-linked mutant VAPB selectively triggers death of motoneurons through a Ca2+-dependent ER-associated pathway. J. Neurochem. 114, 795–809 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev S., Ben Halevy D., Peretti D., Dahan N. (2008). The VAP protein family: from cellular functions to motor neuron disease. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 282–290 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. M., Goodman C. S. (1994). Ectopic and increased expression of Fasciclin II alters motoneuron growth cone guidance. Neuron 13, 507–523 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.-H., Qu J., Suzuki K., Nivet E., Li M., Montserrat N., Yi F., Xu X., Ruiz S., Zhang W. et al. (2012). Progressive degeneration of human neural stem cells caused by pathogenic LRRK2. Nature 491, 603–607 10.1038/nature11557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millecamps S., Salachas F., Cazeneuve C., Gordon P., Bricka B., Camuzat A., Guillot-Noël L., Russaouen O., Bruneteau G., Pradat P. F. et al. (2010). SOD1, ANG, VAPB, TARDBP, and FUS mutations in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: genotype-phenotype correlations. J. Med. Genet. 47, 554–560 10.1136/jmg.2010.077180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitne-Neto M., Machado-Costa M., Marchetto M. C. N., Bengtson M. H., Joazeiro C. A., Tsuda H., Bellen H. J., Silva H. C. A., Oliveira A. S. B., Lazar M. et al. (2011). Downregulation of VAPB expression in motor neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of ALS8 patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3642–3652 10.1093/hmg/ddr284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mórotz G. M., De Vos K. J., Vagnoni A., Ackerley S., Shaw C. E., Miller C. C. J. (2012). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutant VAPBP56S perturbs calcium homeostasis to disrupt axonal transport of mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 1979–1988 10.1093/hmg/dds011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y., Hayashi M., Inada H., Tanaka T. (1999). Molecular cloning and characterization of mammalian homologues of vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated (VAMP-associated) proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 254, 21–26 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A. L., Mitne-Neto M., Silva H. C., Richieri-Costa A., Middleton S., Cascio D., Kok F., Oliveira J. R., Gillingwater T., Webb J. et al. (2004). A mutation in the vesicle-trafficking protein VAPB causes late-onset spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 822–831 10.1086/425287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasinelli P., Brown R. H. (2006). Molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from genetics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 710–723 10.1038/nrn1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennetta G., Hiesinger P. R., Fabian-Fine R., Meinertzhagen I. A., Bellen H. J. (2002). Drosophila VAP-33A directs bouton formation at neuromuscular junctions in a dosage-dependent manner. Neuron 35, 291–306 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00769-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti D., Dahan N., Shimoni E., Hirschberg K., Lev S. (2008). Coordinated lipid transfer between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex requires the VAP proteins and is essential for Golgi-mediated transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3871–3884 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenidou M., Cleveland D. W. (2012). Prion-like spread of protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. J. Exp. Med. 209, 889–893 10.1084/jem.20120741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckelwartz M. J., Kessler E., Zhang Y., Hodzic D., Randles K. N., Morris G., Earley J. U., Hadhazy M., Holaska J. M., Mewborn S. K. et al. (2009). Disruption of nesprin-1 produces an Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy-like phenotype in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 607–620 10.1093/hmg/ddn386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckelwartz M. J., Kessler E. J., Kim G., Dewitt M. M., Zhang Y., Earley J. U., Depreux F. F. S., Holaska J., Mewborn S. K., Pytel P. et al. (2010). Nesprin-1 mutations in human and murine cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 600–608 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L., Qiao T., Beers M., Tan W., Wang H., Yang B., Xu Z. (2013). Widespread aggregation of mutant VAPB associated with ALS does not cause motor neuron degeneration or modulate mutant SOD1 aggregation and toxicity in mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 8, 1–16 10.1186/1750-1326-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnaparkhi A., Lawless G. M., Schweizer F. E., Golshani P., Jackson G. R. (2008). A Drosophila model of ALS: human ALS-associated mutation in VAP33A suggests a dominant negative mechanism. PLoS ONE 3, e2334 10.1371/journal.pone.0002334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezával C., Werbajh S., Ceriani M. F. (2007). Neuronal death in Drosophila triggered by GAL4 accumulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 683–694 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robberecht W., Philips T. (2013). The changing scene of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 248–264 10.1038/nrn3430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J., Hummel T., Ng N., Klämbt C., Davis G. W. (2000). Drosophila Futsch regulates synaptic microtubule organization and is necessary for synaptic growth. Neuron 26, 371–382 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81170-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel P. A., Fabian-Fine R., Kandel E. R. (2000). Mouse VAP33 is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1101–1106 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussan L., Burakov D., Daniels M. P., Toister-Achituv M., Porat A., Yarden Y., Elazar Z. (1999). ERG30, a VAP-33-related protein, functions in protein transport mediated by COPI vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 146, 301–312 10.1083/jcb.146.2.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Matsuoka M. (2011). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant VAPB enhances TDP-43-induced motor neuronal toxicity. J. Neurochem. 119, 1099–1107 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Kanekura K., Levine T. P., Kohno K., Olkkonen V. M., Aiso S., Matsuoka M. (2009). ALS-linked P56S-VAPB, an aggregated loss-of-function mutant of VAPB, predisposes motor neurons to ER stress-related death by inducing aggregation of co-expressed wild-type VAPB. J. Neurochem. 108, 973–985 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuling E., Ahmed S., Haasdijk E., Demmers J., Steinmetz M. O., Akhmanova A., Jaarsma D., Hoogenraad C. C. (2007). Motor neuron disease-associated mutant vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein (VAP) B recruits wild-type VAPs into endoplasmic reticulum-derived tubular aggregates. J. Neurosci. 27, 9801–9815 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2661-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Benito L., Ruiz R., Tabares L. (2012). Synaptic defects in spinal muscular atrophy animal models. Dev. Neurobiol. 72, 126–133 10.1002/dneu.20912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torroja L., Packard M., Gorczyca M., White K., Budnik V. (1999). The Drosophila beta-amyloid precursor protein homolog promotes synapse differentiation at the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 19, 7793–7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H., Han S. M., Yang Y., Tong C., Lin Y. Q., Mohan K., Haueter C., Zoghbi A., Harati Y., Kwan J. et al. (2008). The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 protein VAPB is cleaved, secreted, and acts as a ligand for Eph receptors. Cell 133, 963–977 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujikawa M., Omori Y., Biyanwila J., Malicki J. (2007). Mechanism of positioning the cell nucleus in vertebrate photoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14819–14824 10.1073/pnas.0700178104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor E. L., Galtrey C. M., Perkinton M. S., Lau K. F., De Vos K. J., Mitchell J. C., Ackerley S., Hortobágyi T., Vámos E., Leigh P. N. et al. (2010). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutant vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein-B transgenic mice develop TAR-DNA-binding protein-43 pathology. Neuroscience 167, 774–785 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabulas R. M., Raychaudhuri S., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F. U. (2010). Protein folding in the cytoplasm and the heat shock response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a004390–a004390 10.1101/cshperspect.a004390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk M., van Es M. A., Koppers M., van Rheenen W., Medic J., Schelhaas H. J., van der Kooi A. J., de Visser M., Veldink J. H., van den Berg L. H. (2012). VAPB and C9orf72 mutations in 1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient. Neurobiol. of Aging 33, 2950e1–2950e4 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. F., Shih Y. T., Chen C. Y., Chao H. W., Lee M. J., Hsueh Y. P. (2011). Valosin-containing protein and neurofibromin interact to regulate dendritic spine density. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4820–4837 10.1172/JCI45677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worman H. J., Ostlund C., Wang Y. (2010). Diseases of the nuclear envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000760 10.1101/cshperspect.a000760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Huh S. U., Drennan J. M., Kathuria H., Martinez J. S., Tsuda H., Hall M. C., Clemens J. C. (2012). Drosophila Vap-33 is required for axonal localization of Dscam isoforms. J. Neurosci. 32, 17241–17250 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2834-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo Y. E., Ko C. P. (2011). Treatment with trichostatin A initiated after disease onset delays disease progression and increases survival in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 231, 147–159 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Q., Bailey A. M., Matthies H. J., Renden R. B., Smith M. A., Speese S. D., Rubin G. M., Broadie K. (2001). Drosophila fragile X-related gene regulates the MAP1B homolog Futsch to control synaptic structure and function. Cell 107, 591–603 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00589-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.