Abstract

The normal cornea is transparent which is essential for normal vision and although the angiogenic factor VEGF-A is present in the cornea, its angiogenic activity is impeded by being bound to a soluble form of the VEGF receptor-1 (sVR-1). This report investigates the effect on the balance between VEGF-A and sVR-1 that occurs following ocular infection with HSV, that causes prominent neovascularization, an essential step in the pathogenesis of the vision-impairing lesion, stromal keratitis (SK). We demonstrate that HSV-1 infection causes increased production of VEGF-A, but reduces sVR-1 levels resulting in an imbalance of VEGF-A and sVR-1 levels in ocular tissues. Moreover, the sVR-1 protein made was degraded by the metalloproteinase (MMP) enzymes MMP-2, MMP-7 and MMP-9 produced by infiltrating inflammatory cells that were principally neutrophils. Inhibition of neutrophils, or inhibition of sVR-1 breakdown with the MMP inhibitor (MMPi) marimostat, or the provision of exogenous recombinant sVR-1 protein all resulted in reduced angiogenesis. Our results make the novel observation that ocular neovascularization resulting from HSV infection involves a change in the balance between VEGF-A and its soluble inhibitory receptor. Future therapies aimed to increase the production and activity of sVR-1 protein could benefit the management of SK, an important cause of human blindness.

Introduction

Normal ocular function requires that photons can passage through ocular tissues anterior to the retina with minimal impedance. In consequence, tissues anterior to the retina are transparent and numerous strategies are used by the normal eye to maintain transparency. These include mechanisms to suppress inflammatory and immune reactions and means to suppress ocular vascularization, both enemies of normal vision (1, 2). Nevertheless, in some circumstances, damage to the eye can result in chronic inflammatory reactions and/or pathological neovascularization and these events may seriously impair vision. This is often the outcome of ocular infection with Herpes Simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) (3,4). Invariably, HSV-1 infection is followed by lifelong viral persistence and this source of virus can give rise to subsequent infections in the cornea (5, 6). Repeated recurrences often result in significant vision impairing lesions that occur mainly in the corneal stroma (5, 6). Such stromal keratitis (SK) lesions have a complex pathogenesis but result mainly from T cell orchestrated immunopathological reactions to viral or perhaps unmasked ocular antigens (5, 7). Characteristically, SK also includes pathological neovascularization that can be extensive, especially in animal models of SK (8).

The therapeutic management of SK usually targets the inflammatory reaction but controlling pathological angiogenesis also represents a useful approach, as has been demonstrated in experimental situations (9, 10). Although several molecules may be involved in pathological neovascularization, the VEGF family of proteins, especially VEGF-A signaling through the VEGFR-2 receptor, is likely to be the most consequential (11, 12). In support of this, inhibiting VEGF-A, or interfering with its receptor function, were shown to be effective therapeutic strategies in mice models of SK (8–10).

One unsolved issue with regard to VEGF-A and pathological angiogenesis in SK, is the source of the VEGF-A that induces neovascularization. Initial studies indicated that VEGF-A was synthesized de novo in epithelial cells as a consequence of the infection, although it is not clear if the primary source of VEGF-A is virus infected cells themselves or nearby cells exposed to products released from infected and dying cells (13, 14). Another VEGF-A source, especially after the initial event of SK pathogenesis, may be infiltrating inflammatory cells, especially neutrophils that are prominent cells in SK lesions (8). More recently, it was realized that VEGF-A is continuously produced in biologically functional amounts by corneal epithelial cells. However, this source of VEGF-A fails to mediate angiogenesis because it is bound to a soluble form of the VEGF receptor 1 (sVR-1) (15). This so-called VEGF-A trap may be the primary reason the undamaged cornea is not vascularized (15). Curiously, angiogenesis can be elicited in the normal eye if the bond between VEGF-A and sVR-1 is disrupted in some way (15). Of interest, some species fail to express sVR-1 and in one genetic disease of humans, synthesis of the sVR-1 molecule is defective (16). Both situations result in corneal vascularization.

In light of the existence of the VEGF-A trap in normal eyes, pathological angiogenesis, as for example can occur after HSV-1 infection, could also be influenced by the balance between VEGF-A and the sVR-1 molecules. We analyze this possibility in the present communication. Our results confirm the previous report that VEFG-A is present and bound to sVR-1 in normal ocular tissue (15). We further show that one consequence of HSV-1 infection is the occurrence of an imbalance in the levels of VEGF-A and sVR-1 mRNA and proteins. Our results could mean that therapies designed to increase the presence, or retard the breakdown, of sVR-1 may be useful approaches to help manage the severity of SK, an important cause of blindness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, Virus and cell lines

Female 6 to 8 week old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN. Animals were housed in the animal facilities approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) at The University of Tennessee and all experimental procedures were in complete agreement with the Association for research in Vision and Ophthalmology resolution on the use of animals in research. HSV-1 RE Tumpey and HSV-KOS viruses were grown in Vero Cell monolayers (ATCC no. CCL81, American Type Culture Collection). The virus was concentrated, titrated, and stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. MK/T-1 cell line (Immortalised keratocytes from C57/BL6 mouse corneal stroma) was kindly gifted by Dr. Reza Dana, Schepens Eye Research Institute and Department of Ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School, Boston MA.

Corneal HSV-1 Infection and Clinical Scoring

Corneal infections of C57BL/6 mice were conducted under deep anaesthesia induced by i.p. injection of avertin as previously described (8). Mice were scarified on their corneas with 27-gauge needle, and a 3-μl drop containing 1×104 PFU of virus was applied to the eye. The eyes were examined on different days pi for the development and progression of clinical lesion by slit-lamp biomicroscope (Kowa Company, Nagoya, Japan). The progression of SK lesion severity and angiogenesis of individually scored mice was recorded. The scoring system was as follows: 0, normal cornea; +1, mild corneal haze; +2, moderate corneal opacity or scarring; +3, severe corneal opacity but iris visible; +4, opaque cornea and corneal ulcer; +5, corneal rupture and necrotizing keratitis. The severity of angiogenesis was recorded as described previously (17). According to this system, a grade of 4 for a given quadrant of the circle represents a centripetal growth of 1.5 cm towards the corneal center. The score of the four quadrants of the eye were then summed to derive the neo vessel index (range 0–16) for each eye at a given time point.

Sub-conjunctival Injection

Subconjunctival injections of different drugs were performed as described previously (18). Briefly, subconjunctival injections were done using a 2-cm, 32-gauge needle and syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) to penetrate the perivascular region of conjunctiva, and the required dose of sVR- 1 or MMPi was delivered into subconjunctival space. Control mice received isotype fusion protein or solvent used for MMPi.

Treatment of mice with rsVR-1 and MMP inhibitor

6- to 8-wk-old C57/BL6 mice were ocularly infected under deep anesthesia with 1×104 PFU of HSV-1 RE Tumpey and divided randomly into groups. One group of mice was administered with 5 μg of rsVR-1 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in 7 μl PBS subconjunctivally on 36 hours p.i. and then every alternate day from day 5 until day 13 postinfection. In some experiments, rsVR-1 was injected subconjunctivally every alternate day starting from day 7 until day 13 postinfection. Animals in the control group were given recombinant human IgG1 Fc protein (R & D Systems) following either of the regimens for respective experiment. The MMPi, marimastat (200 μg/mouse) (Tocris Cookson Inc, Ellisville, MO) was administered subconjunctivally either starting from day 2 or day 5 pi followed by every alternate day until day 13pi. Mice in the control group were given the mock injections. Mice were observed for the development and progression of angiogenesis and SK lesions severity from day 7 until day 15 pi. In some experiments MMPi treatment was started from day 2 and continued every alternate day until day 6 pi. Mice were sacrificed on day 7 pi and corneas were collected for further analysis. All the experiments were repeated at least two times.

Neutrophil Depletion with mAb

6- to 8- week old C57/BL6 mice were ocularly infected under deep anesthesia with 1×104 PFU of HSV-1 RE Tumpey and divided randomly into groups. One group of animals was administered with 100 μg of anti-Gr-1 mAb (RB6-8C5; BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH) intraperitoneally on day 7 and 9 pi. Experiments were terminated on day 11 pi and corneal samples were collected for further analysis. To study the effect of neutrophil depletion on HSV-1 mediated corneal angiogenesis, antibody treatment was given every alternate day starting from day 7 until day 13 pi. Mice were observed for the development and progression of angiogenesis and SK lesions until day 15 pi. Animals in control group were given isotype control (IgG2b) Ab (LTF-2; BioXcell) following the same regimen. All experiments were repeated at least two times.

Immunofluorescence staining

For immunofluorescence staining, the eyes from naïve uninfected mice were enucleated, and snap frozen in OCT compound. Six-micron thick sections were cut, air dried, and fixed in acetone-methanol (1:1) at room −20 °C for 10 min. Sections were blocked with 10% goat serum containing 0.05% Tween20 and 1:200 dilution of Fc block (Clone 2.42G2; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Rat anti-sVR-1 (141515; R & D Systems) was diluted in 1% BSA containing 0.1% Triton-X and incubated at room temp for 1 hr. After incubations sections were washed several times with PBST and then stained with rabbit anti rat Alexa-488 for 45 min. The corneal sections were repeatedly washed with PBST and mounted with ProLong gold antifade mounting media containing DAPI as a nuclear stain (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) and visualized under a Immunofluorescence microscope. For Whole mount corneal staining, corneas from rsVR-1 and Isotype treated mice were dissected under stereomicroscope. Corneal whole mounts were rinsed in PB for 30 min and flattened on a glass slide under stereomicroscope. Corneal flat mounts were dried and fixed in 100% acetone for 10 min at −20°C. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% BSA containing 1:200 dilution of Fc block for 2 hr at 37°C. CD31-PE (MEC13.3; BD Biosciences-Pharmingen) antibody was used t a concentration of 1:250 in 1% BSA for overnight followed by subsequent washes in PBS. Corneas were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade and visualized with fluorescence microscope.

Purification of Neutrophils

Ly6G+ neutrophils were purified from the pooled liberase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) digested corneal single cell suspension obtained from HSV infected mice using anti-Ly6G+ microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The purity was achieved at the extent of 90%. Purified neutrophils were further analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR and WB for the expression of different MMPs.

Flow Cytometry

Corneas were excised, pooled group wise, and digested with 60 U/ml Liberase for 35 minutes at 37°C in a humified atmosphere of 5% CO2. After incubation, the corneas were disrupted by grinding with a syringe plunger on a cell strainer and a single-cell suspension was made in complete RPMI 1640 medium. The single cell suspensions obtained from corneas were stained for different cell surface molecules for FACS. All steps performed at 4°C. Briefly, cell suspension was first blocked with an unconjugated anti-CD32/CD16 mAb for 30 min in FACS buffer. After washing with FACS buffer, samples were incubated with CD45-allophycocyanin (30-F11), CD11b-PerCP (M1/79), Ly6G-PE (1A8), CD4-allophycocyanin (RM4.5) (All from BD Biosciences-Pharmingen) for 30 min on ice. Finally, the cells were washed three times and re-suspended in 1% para-formaldehyde. The stained samples were acquired with a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences) and the data were analyzed using the FlowJo software.

Quantitative PCR (QPCR)

Corneal cells were lysed and total mRNA was extracted using TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen). Total cDNA was made with 1 μg of RNA using oligo(dT) primer. Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA) with iQ5 real-time PCR detection ssystme (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA). The expression levels of different molecules were normalized to β-actin using ΔCt calculation. Relative expression between control and experimental groups were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt formula. The PCR primers used are included as table 1 in Supplemental information.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR was performed to detect the presence of mRNA transcripts of various molecules (VEGF-A, sVR1, beta actin and different MMPs) according to manufacturers protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, cDNA was prepared from total mRNA extracted from different samples. cDNAs were amplified by PCR and were resolved on 1% agarose gel The PCR primers used are included as table 1 in Supplemental information. The PCR primers used are shown in table 2 in Supplemental information.

Western blot analysis

The supernatants from lysed corneal cells were quantified using BCA protein Assay kit (Thermo scientific, Waltham, MA) using BSA as a standard and samples with equal protein concentrations were denatured by boiling in Laemmli buffer. Polypeptides were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with Tween20 (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween20) overnight at 4°C and probed with specific primary and secondary antibodies. Proteins were detected using chemiluminiscent HRP substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was kept in stripping buffer for 10 min and re-probed using anti-β-actin antibody. The antibodies used were rat anti-sVR-1 (141515; R&D Systems), mouse anti-VEGF-A (EE02; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti MMP-2 (8B4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), goat anti mouse MMP-8 (M-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), goat anti mouse MMP-9 (C-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), goat anti mouse MMP-12 (M-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-β-actin (AC74; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO), goat anti rat IgG-HRP (R & D Systems), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and donkey anti goat IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Coimmunoprecipitation

Coimmunoprecipitation was performed using Pierce Coimmunoprecipitation kit according to manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Scientific). Briefly, 50 μg of anti sVR-1 antibody was immobilized to antibody coupling resin by incubating the antibody to resin containing column for 2 hrs at room temperature. Care was taken to keep resin slurry in suspension during incubation. The 200 μl supernatant from lysed corneal cells (800 μg of total protein) was incubated for 2 hrs at 4°C with the above mentioned resin immobilized antibody. Finally, 50 μl of the elution buffer was added and immunoprecipitate was eluted out and analyzed by WB.

ELISA

The pooled corneal samples were homogenized using a tissue homogenizer and supernatant was used for analysis. The concentrations of VEGF-A and sVR-1 were measured using Quantikine sandwich ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to manufacturers protocol.

Quantification of total number of molecules for sVR-1 and VEGF-A

The total number of sVR-1 and VEGF-A molecules from naïve as well as different day pi samples were calculated using following formula.

In vitro assay for VEGF-A and sVR-1 production

A mouse stromal fibroblast cell line (MK/T-1) was used to study differential effect of HSV-1 on production of VEGF-A and sVR-1. The cells were cultured and plated onto 6-well tissue culture plates in 10% DMEM. The cells around >90% confluents were infected with HSV-KOS at 3 multiplicity of infection (MOI) (adsorbption for 1 h). Uninfected cells were used as control. Cells were harvested at different time points and total mRNA was extracted and used to quantify the mRNA levels of the VEGF-A and sVR-1.

Degradation assays

Degradation assays were performed as previously described (19). Briefly, 100 ng of rsVR-1 (R&D Systems) was incubated with active mouse MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12 (R&D Systems), at 1:1 substrate/enzyme molar ratio at 37°C for 24 hours. Pro-MMPs were activated by p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) before use according to manufacturer’s protocol. To study the degradation of mouse native sVR-1 from cornea, the supernatant from lysed corneal cells was collected and incubated with different activated MMPs [1:1 substrate enzyme molar ratios] at 37°C for 24 hours. MMP activity was inhibited using 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The samples were then analyzed by WB.

Statistics

Student’s t test was performed to determine statistical significance and data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Presence of VEGF-A in ocular tissues of normal mice

Recently, it was demonstrated that VEGF-A is present in normal corneal tissues, but it fails to induce angiogenesis because it is bound to sVR-1 (15). Both VEGF-A and sVR-1 are produced continuously by normal ocular tissues. As a prelude to measuring the influence of HSV-1 ocular infection on the balance between VEGF-A and sVR-1, we repeated some of the normal mice experiments previously described (15). We were able to confirm many of their observations. Accordingly, as shown in Figure-1, corneal extracts from naïve mice analyzed by WB under reducing conditions revealed a band of 62kDa for sVR-1 and two bands for VEGF-A at molecular sizes of 22 and 14 kDa (Figure 1A). These bands correspond to two isoforms of VEGF-A. However, under non-reducing conditions, blots revealed only a single band that was far larger than those observed in reducing gels and had an apparent size of between 100–150 kDa (Figure 1B). This would be consistent with VEGF-A being bound to another molecule, presumably sVR-1. Support for this was obtained performing co-immunoprecipitation that revealed the interaction of VEGF-A and sVR-1 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Normal cornea expresses VEGF-A bound to sVR-1.

WT mice were sacrificed and 4 to 6 corneas were collected and pooled for WB, Co-immunoprecipitation, and mRNA analysis by RTPCR. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) Reducing WB analysis for sVR-1 and VEGF-A reveals presence of sVR-1 at 62 kDa and two isoforms of VEGF-A at 22 and 16 kDa in normal cornea. (B) Non-reducing WB for VEGF-A shows the presence of a much larger band between molecular size of 100 to 150 kDa consistent with its being the bound form. (C) sVR-1 was immunoprecipitated from normal corneal extracts, with anti sVR-1 mAb and the complex was analyzed for the co-immunoprecipitation of VEGF-A by WB. Normal cornea shows the presence of VEGF-A bound to sVR-1. (D) Agarose gel analysis of VEGF-A (214bp) (lane 3) and sVR-1 (358bp) (lane 5) cDNA from normal uninfected cornea. Lane M-marker, lane 1- β-actin (92bp), lane 2, 4 and 6 are reverse transcriptase negative controls for β- actin, VEGF-A and sVR-1. (E) Representative immunofluorescence staining of corneal section for sVR-1 (green, left panel), nuclei (blue, middle panel) reveals the presence of sVR-1 mainly in the corneal epithelial layer and to a lesser extent in the stroma (Merge). Nuclei were stained (blue) with DAPI. Image is representative of two independent experiments. Original magnification × 10.

The fact that normal ocular tissue expressed mRNA for both the VEGF-A and the sVR-1 proteins was also demonstrated by RTPCR (Figure 1D). The sVR-1 molecule was also readily detectable in epithelial and stromal layers of corneal sections by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1E). Our findings are consistent with and confirm those reported by the Ambati group and demonstrate that VEGF-A is present in cornea and is mostly bound to sVR-1 forming a so called VEGF-A trap (15, 20–21).

Changes in VEGF-A and sVR-1 as a consequence of HSV-1 infection

The principal objective of our study was to evaluate if the VEGF-A trap affected the outcome of pathological angiogenesis caused by ocular infection with HSV-1. To do this, mice were ocularly infected with virus and the expression levels of both VEGF-A and sVR-1 mRNA and proteins were measured and compared with controls at various times pi. We focused on initial time points after infection when replicating virus is readily detectable in the cornea (up to 5 day pi) as well as at the stage of clinical SK (day 8 pi) when replicating virus is no longer demonstrable and the stroma is heavily infiltrated by inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils (4, 22). At each time point, 6 corneas were collected and pooled for analysis from infected and control animals by QPCR. The data expressed in Figure 2A records average gene expression values compared with controls for 2 separate experiments. As is evident, increased VEGF-A expression (6.7 fold) was detectable by 24 hours pi and levels peaked in the early phase (average 11.5 fold) in samples tested on days 2 pi. By day 5, VEGF-A mRNA expression levels were at control levels. However, VEGF-A mRNA levels increased in later samples with the highest levels detectable (average 97 fold) in day 11 samples. At day 11, replicating virus and viral mRNA were no longer present in corneal extracts (data not shown) and the VEGF-A that was detected was presumed to be produced mainly by infiltrating inflammatory cells such as neutrophils (described subsequently).

Figure 2. Corneal HSV-1 infection causes an imbalance between VEGFA and sVR-1.

WT mice corneas were scarified and infected with 104 PFU of HSV in PBS or mock infected with only PBS (naïve control mice). Corneas were harvested from infected mice at indicated time points PI and from naive control mice at 24 hr. (A) At each time point 6 corneas were collected and pooled for mRNA extraction. The expression levels of VEGF-A molecule were normalized to β-actin using ΔCt calculation. Relative expression between control and infected groups were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt formula. Kinetic analysis for the expression of VEGF-A mRNA by quantitative PCR (QPCR) at different days pi. The expression of VEGF-A shows a biphasic upregulation pattern, early on day 2 pi and then again on day 11 pi as compared to naïve cornea. Figure is a summary of two independent experiments and each experiment represent group of 6 corneas. (B) At each time point 6 corneas were harvested from infected or naïve mice and the levels of VEGF-A were determined by ELISA. Quantification of VEGF-A protein levels in the normal and infected corneas at different days pi reveals similar pattern as that of gene expression. Figure is a summary of at least two independent experiments and each experiment represent group of 6 corneas. P ≤ 0.009 (**), P = 0.0004 (***). (C) At each indicated time points 3–4 corneas were harvested and total protein concentration were measured by BCA protein assay. Samples with equal protein concentration were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by WB analysis. VEGF-A expression was analyzed by WB analysis showed an increase in the VEGF-A protein levels at different days pi compared to naïve control mice. (D) Three to four corneas were harvested from day 3 pi or naïve control mice at 24 hr pi. Samples with equal protein concentration were subjected to native-PAGE followed by WB analysis. The left figure shows a band of molecular size between 100 to 150 kDa in naïve corneal sample. The right is from day 3 infected corneas. It shows the large 100–150 kDa band as well as another at 50 kDa indicating the presence of both bound and free VEGF-A. (E) Kinetic analysis for the expression of sVR-1 mRNA by QPCR at different days pi. Relative change in the expression of sVR-1 mRNA at different days pi as compared to the uninfected mice revealed a sharp decrease in the sVR-1 expression from day 3 pi which reached above normal around day 11 pi and back to normal levels at day 14 pi. The figure is a summary of two independent experiments and each experiment represent group of 6 corneas. (F) sVR-1 protein levels analyzed by ELISA from the normal and infected corneas at different days pi shows an early decrease after HSV-1 infection which reaches to level found in normal controls at day 14 pi. The figure is a summary of at least two independent experiments and each experiment represent group of 6 corneas. P ≤ 0.05 (*), P = 0.0023 (**), P ≤ 0.0001 (***). (G) Quantification of total number of sVR-1 molecules per VEGF-A molecule from naïve and infected corneas at different days pi using protein quantities obtained by ELISA (B & F) shows the significant reduction of total number of sVR-1 molecules per VEGF-A molecule on day 1 and from day 7 to 14 pi. The total number of molecules for sVR-1 and VEGF-A were calculated by multiplying the total quantity of the protein by its molecular weight and Avogadro’s number. The figure is a summary of values obtained from figure B and F. P = 0.0216 (*), P ≤ 0.0032 (**), P ≤ 0.0002 (***). (H) Reducing WB analysis for sVR-1 from uninfected and infected corneas at different time pi shows degradation of sVR-1 after HSV-1 infection. Degraded products are shown by black arrowhead.

The general pattern observed measuring VEGF-A gene expression was evident with protein levels measured by ELISA and WB. As shown in Figure 2B and 2C, after an initial peak of VEGF-A protein on days 2 to 3 pi, a second higher peak was observed during the clinical phase. The non-reducing WB of corneal extracts from naïve mice revealed single high molecular weight band for VEGF-A (presumably all bound to sVR-1). However, corneal extracts from day 3 pi showed another low molecular weight band for VEGF-A suggesting the presence of non sVR-1 associated free VEGF-A after HSV-1 infection (Figure 2D).

Quantification of sVR-1 gene expression revealed a different response pattern than was noted with VEGF-A (Figure 2E). The expression levels were decreased following HSV-1 infection with maximal decreases observed in samples taken at 5 days pi (average 8 fold compared to control). The initial decreased expression of sVR-1 could reflect the well known ability of HSV to suppress almost all host gene expression in cells in which it replicates (23, 24). However, VEGF-A gene expression, at least early after infection, may be an exception as are some cytokines (13, 25, 26). To determine if HSV infection could differentially influence the expression of VEGF-A and sVR-1, we studied the outcome of in vitro infection of an eye derived cell line (MK/T-1) that spontaneously expressed both VEGF-A and sVR-1 (Supplemental Figure 1A). This cell line was derived from corneal stromal fibroblasts. The results demonstrate that early after HSV-1 infection whereas VEGF-A levels were increased, levels of sVR-1 mRNA were markedly suppressed (Supplemental Figure 1B). Although fibroblasts are not the major cell type infected by HSV in vivo, our results imply that a similar outcome could occur in corneal epithelial cells, the primary target cells for HSV infection.

Experiments were also done to quantify protein levels at various time points by ELISA. In corneal extracts of uninfected animals, sVR-1 protein was readily detectable, and these levels were far higher than VEGF-A in the same samples (Figure 2F). Changes in sVR-1 protein levels detectable by ELISA did occur at different time points after infection, and significant reduction in the levels of sVR-1 were observed on day 1 and from day 5 to 11 pi. Additionally, when the ratio of the number of sVR-1 molecules to VEGF-A molecules from naïve mice was compared with infected animals at various time points pi, there was a decreased ratio of sVR-1 to VEGF-A at all time points pi. Differences were significant on day 1 as well as from day 7 to 14 pi (Figure 2H). Furthermore, an interesting situation was revealed by WB analysis under reducing conditions of samples taken at different time point pi (Figure 2H). Here it was evident in corneal extracts from uninfected animals that sVR-1 protein was represented almost entirely as a single band at approximately 60 kDa size. However, by day 3 pi, there was notable fragmentation of the sVR-1 and this situation was also evident in samples collected at other time points after infection. The degradation of sVR-1 could explain why we observed minimal sVR-1 protein at day 11-time point even though sVR-1 mRNA levels peaked at this time. These observations led us to conclude that HSV infection of the cornea diminished the expression of sVR-1 and that the intact protein was degraded, at least partially, at different phases of virus infection. Both effects would serve to diminish the inhibitory activity of sVR-1 on VEGF-A induced angiogenesis.

An additional series of experiments supported the notion that the activity of sVR-1 has a constraining effect on the angiogenic activity of VEGF-A. We anticipated that the provision of an additional exogenous source of sVR-1 protein to HSV-1 infected mice might act to diminish the extent of angiogenesis that occurs subsequent to infection. To evaluate this possibility, we obtained recombinant mouse sVR-1 (rsVR-1) fusion protein that had previously been used by others to counteract VEGF-A activity in a VEGF-A induced micro-pocket assay for angiogenesis (15). In our pathological system, we chose to administer a higher dose rsVR-1, or an isotype fusion protein (Isotype). To evaluate the possible VEGF-A inhibitory effects in vivo, animals were given either rsVR-1 or Isotype subconjunctivally to HSV-1 infected animals, either starting at day 1 (Figure 3A) or day 7 pi (Figure 3E). Animals were followed until day 15 pi to measure the extent of angiogenesis. Results shown in Figure 3A–C and Supplemental Figure 2A indicated that rsVR-1 recipients had significantly diminished angiogenic responses as well as SK lesion severity compared to the isotype group. Corneal cell preparations collected at the end of the experiment revealed diminished frequency and numbers of CD31+ (a marker for blood vessel endothelial cells), neutrophils as well as CD4+ T cells (Figure 3D and Supplemental Figure 2B). It is of particular interest to note that even when rsVR-1 administration was delayed till day 7 pi (Figure 3E), a significant level of SK severity and angiogenesis inhibition was still evident. These results further support the concept that sVR-1 may limit the angiogenic response to VEGF-A in pathological angiogenesis.

Figure 3. rsVR-1 administration hinders angiogenic activity of VEGF-A and inhibits corneal angiogenesis post HSV-1 infection.

WT mice were ocularly infected by corneal scarification with 104 PFU of HSV. (A) rsVR-1 or isotype Fc protein were administered subconjunctivally at 5 μg/eye as shown. The extent of angiogenesis and SK lesion severity in the eyes of HSV infected mice were quantified in a blinded manner using a scale as described in materials and methods. The progression of angiogenesis and SK lesion severity were significantly reduced in the group of mice treated with rsVR-1 as compared to isotype treated mice. Data are representative two independent experiments (n = 10–12 mice/group). P ≤ 0.0007 (***). (B) Representative whole mount corneas stained for CD31 (lower panel) at day 15 pi shows reduced angiogenic response in rsVR-1 treated mouse. Bars, 100μm. (C) Representative eye photos shows reduced SK lesion severity as well as angiogenesis from rsVR-1 treated mouse compared to isotype treated mouse. (D) rsVR-1 or isotype Fc protein treated mice were sacrifice on day 15 pi and corneas were collected for surface staining of eye infiltrating cells. Total cell numbers per cornea for CD31+ cells, Neutrophils (CD11b+, Ly6G+ cells) gated on total CD45+ cells and CD4+ T cells showed the significant reduction in total numbers of the respective cell population from rsVR-1 treated mice as compared to the isotype treated mice. Data are a representative of two independent experiments (n = 3–5/group). P = 0.012 (*), P ≤ 0.0015 (**). (E) Therapeutic administration of the rsVR-1 was started from day 7 pi when SK becomes visibly evident. Therapeutic administration of rsVR-1 also showed significant reduction in angiogenesis as well as lesion severity further confirming the inhibitory effect of sVR-1 on the angiogenic activity of VEGF-A. Data are a representative of two independent experiments (n = 8 mice/group). P ≤ 0.012 (*).

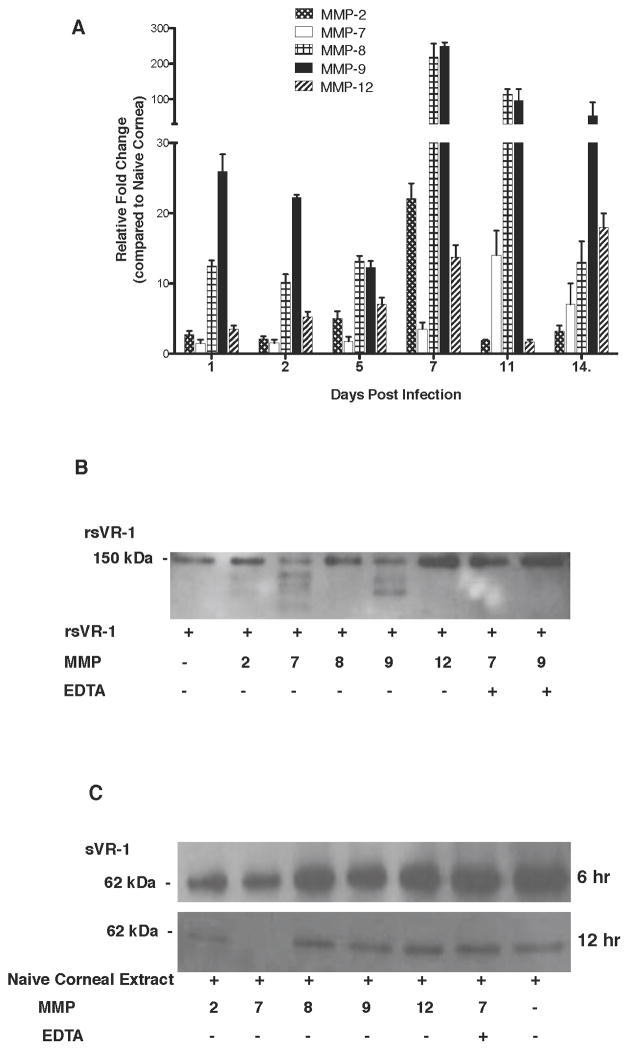

Metalloproteinases could be responsible for sVR-1 degradation

The observation that sVR-1 protein may be degraded in HSV-1 infected corneas raised the question of how the breakdown was accomplished. Likely enzyme candidates include MMPs, some of which were shown to be present in damaged eyes in other systems (1). Previous reports suggest that MMP-9 could induce neovascularization in vivo and inhibition of MMP-9 reduces angiogenesis (27). Moreover, MMP-9 protein is present in the cornea following HSV-1 infection as we have reported previously (28). Experiments were performed to measure the expression profile by QPCR of several MMP mRNAs at various time points after HSV-1 infection. The results shown in Figure-4A demonstrate that compared to uninfected controls, expression levels of several MMPs were elevated following the infection. Peak levels that varied between experiments differed between the MMPs tested, but always occurred between days 5 and days 11 pi. Of the multiple MMP mRNAs examined, expression levels of MMP-9 were the most elevated with its peak evident in day 7 pi samples (Average 249 fold). Another MMP of interest was MMP-7 since this enzyme was shown recently to be uniquely capable degrading human sVR-1 (19). Levels of MMP-7 were at their peak on day 11 pi. Additional experiments were done in vitro with the activated form of selected MMPs (MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, and MMP-12) to measure their ability to degrade rsVR-1 in vitro as detected by WB. As is evident in Figure-4B, MMP-7 was most effective at degrading rsVR-1 with MMP-9 also active, but less so. In these assays, MMP-8 and MMP-12 were without activity and MMP-2 had a minimal effect. In additional experiments, MMP-2, MMP-7 and MMP-9 were shown to degrade sVR-1 present in naïve corneal extracts (Figure-4C).

Figure 4. Metalloproteinases are upregulated after HSV-1 infection and MMP-2, 7 and 9 degrades rsVR-1 and sVR-1.

(A) WT mice corneas were scarified and infected with 104 PFU of HSV in PBS or mock infected with only PBS (naïve control mice). Corneas were harvested from infected mice at indicated time points PI and from naive control mice at 24 hr. At each time point 6 corneas were collected and pooled for mRNA extraction. The expression levels of different MMP molecule were normalized to β-actin using ΔCt calculation. Relative expression between control and infected groups were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt formula. Kinetic analysis for the relative fold change in the expression levels of MMP- 2, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12 mRNAs at different days pi. The mRNA expression of all the tested MMPs was upregulated in biphasic manner post HSV-1 infection with the first peak expression at day 1 pi and maximum expression between day 7 and day 11 pi. (B) Mouse rsVR-1 was incubated with activated form of MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12 for 12 hrs at 37°C and analyzed by WB. MMP-7 (lane 3) showed maximum degradation of rsVR-1 followed by MMP-9 (lane 5) and MMP-2 (lane 2). Addition of the MMP inhibitor, EDTA, inhibited the degradation of rsVR-1 by MMP-7 (lane 7) and MMP-9 (lane 8). Figure is a representative of three independent experiments. (C) Corneal lysates from 4–6 pooled corneas of uninfected WT mice were incubated with activated form MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12 either for 6 hr or 12 hr at 37°C. The digested corneal lysates were analyzed by WB for sVR-1. MMP-7 showed degradation of corneal sVR-1 even after 6 hrs of incubation (upper panel, lane 2), with complete degradation after 12 hrs of incubation (lower panel, lane 2). MMP-2 (lower panel, lane 1) and MMP-9 (Lower panel lane 4) also showed degradation of corneal sVR-1 after 12 hrs of incubation. Addition of MMP inhibitor EDTA with MMP-7 (lane 6) showed inhibition of sVR-1 degradation. Figure is a representative of three independent experiments.

Experiments were also done to determine if inhibiting the function of MMP enzymes in vivo affected sVR-1 degradation, as well the outcome on the extent of angiogenesis and SK severity. To accomplish MMP inhibition, marimastat (29–31) was administered subconjunctivally at different times pi and the results compared to infected mice given subconjunctival injections of mock. In an experiment in which animals received marimastat on days 2,4 and 6 pi, corneal extracts examined by WB on day 7 pi revealed a markedly reduced level of sVR-1 degradation compared to controls (Figure-5A). In another experiment, two marimastat injections given on days 2 and 4 also revealed inhibited sVR-1 degradation in samples examined on day 5 (Data not shown).

Figure 5. Blocking MMPs activity in vivo rescues sVR-1 degradation and diminishes angiogenesis and SK severity.

WT mice corneas were scarified and infected with 104 PFU of HSV or mock infected with only PBS (naïve control mice). Marimastat, a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor (MMPi) was administered subconjunctivally at 200 ug/mouse as shown. Mice in control group received HSV infection with mock treatment. (A) WB analysis of the corneal lysates collected from naïve (N), control treated (C) and MMPi treated mice at day 7 pi shows that MMPi rescues degradation of sVR-1 post HSV-1 infection. The figure is a representative of two independent experiments. (B) Preventive treatment of MMPi in mice infected with HSV-1 was started from day 2 pi as shown. MMPi treatment showed a significant reduction of angiogenesis as well as SK lesion severity at day 15 pi. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 9–12 mice/group). P ≤ 0.04 (*), P = 0.0065 (**). (C) MMPi treated or control mice were sacrifice on day 15 pi and corneas were collected for surface staining of eye infiltrating cells. Analysis for total cell numbers per cornea for CD31+ cells, neutrophils (CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G+ cells) and CD4+ T cells showed significant reduction in frequencies as well as total numbers of the respective cell population in the MMPi treated mice. Data are a representative of two independent experiments (n = 7/group). P = 0.0115 (*), P = 0.0078 (**), P = 0.0002 (***). (D) Therapeutic administration of the MMPi (started from day 5 pi), also showed reduced angiogenesis as well as SK lesion severity at day 15 pi. Data are a summary of two independent experiments (n = 6 mice/group). P ≤ 0.021 (*). (E) Analysis of total cell numbers per cornea for CD31+ cells, neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+, Ly6G+ cells) and CD4+ T cells also showed the significant reduction in the total cell numbers per cornea after preventive MMPi treatment. Data are a representative of two independent experiments (n = 5–6/group). P ≤ 0.0094 (**).

When the outcome of angiogenesis and SK severity was compared in treated and control mice, the marimastat recipients had significantly reduced levels of angiogenesis and SK severity, at least at day 15 pi time point when experiments were terminated (Figure 5B). Corneal cell preparations collected at the end of the experiment revealed diminished frequency and numbers of CD31+ endothelial cells, neutrophils and CD4+ T cells (Figure 5C and Supplemental Figure 3A). Furthermore, in an experiment in which marimastat treatment was begun on day 5 pi and given additional injections on days 7, 9 and 11 there was also a significant reduction of angiogenesis and lesion scores at day 15 pi (Figure 5D). Corneal cell preparations collected at the end of the experiment revealed diminished frequency and numbers of CD31+ endothelial cells, neutrophils as well as CD4+ T cells (Figure 5E and Supplemental Figure 3B). Taken together our results support the concept that metalloproteinases, particularly MMP-2, MMP-7 and MMP-9, are upregulated following HSV-1 infection and these enzymes are responsible for degrading the sVR-1 protein that, in turn, constrains the angiogenic activity of VEGF-A.

Neutrophils play multiple roles in ocular angiogenesis

A prominent cell type in the inflammatory response to ocular HSV-1 infection is the neutrophil (8, 13, 22). To investigate the role played by neutrophils in HSV-1 mediated corneal angiogenesis, kinetic studies were carried out for neutrophil infiltration in the cornea following HSV infection. As shown in Figure 6A, neutrophils constitute about 30–80% of total infiltrated leukocytes at all tested time points and infiltrate the cornea in a biphasic manner. An initial wave of infiltration peaked around day 2 pi followed by decline and second wave starting from day 8 till which peaked around day 15 pi (Figure 6B). Since, neutrophils studied in other systems are known to be a source of different MMPs as well as VEGF-A (28, 32–34); we anticipated that neutrophils could be a source of MMP enzymes that act to increase angiogenesis by breaking down and releasing bioactive VEGF-A from its bond to sVR-1. In support of this, we purified neutrophils from the day 2 infected corneas and WB analysis was carried out to check the presence of protein for MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12. Figure 6C shows the presence of MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12. Additionally, depleting neutrophils from day 7 pi (Figure 6D) in infected mice led to significantly diminished VEGF-A protein levels and restored levels of sVR-1 protein in day 11 samples (Figure 6E). QPCR analysis also revealed the decreased expression of VEGF-A and MMP-9 in the depleted mice as compared to isotype antibody treated mice (Figure 6F). To further implicate neutrophils as a source of VEGF-A during the clinical phase of SK, neutrophils were purified from pooled corneas at day 11 pi and RTPCR and WB carried out to check for the presence of VEGF-A mRNA message as well as protein. Both VEGF-A mRNA (Figure 6G) and protein (Figure 6H) could be demonstrated supporting a role for neutrophils in contributing to angiogenesis during the clinical phase of SK when replicating virus is no longer present in the cornea.

Figure 6. Neutrophil, the principal cell in cornea after HSV-1 infection is source of MMPs and VEGF-A.

WT mice corneas were scarified and infected with 104 PFU of HSV or mock infected with only PBS (naïve control mice). At each indicated day pi two mice were sacrificed, corneas were harvested and single cell suspensions were analyzed for surface staining by flow cytometry. (A) Representative FACS plot from each time point shows the percentage of neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) gated on total CD45+ cells. (B) Total number of neutrophils per cornea at each indicated time point post HSV-1 infection. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Figure is a summary of two independent experiments and each experiment represent group of 2 corneas. (C) Ly6G+ neutrophils were purified from day 2 pi corneas using anti-Ly6G beads. Cell suspension from 6–8 pooled corneas was used for neutrophil purification. Western blot analysis for MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-9 and MMP-12 from purified neutrophils. Data is from single experiment and represent neutrophils from group 6–8 corneas. (D) Neutrophil depletion was carried out from day 7 pi, using anti-Gr-1 mAb (100 μg/mice, intra-peritoneally) as shown. Mice in the control group received isotype control antibody. Representative FACS plot shows complete depletion of neutrophils from spleen (upper panel) and cornea (lower panel) analyzed at day 11 pi. (E) Corneal lysates from normal (N), isotype control antibody treated (IC) and neutrophil depleted (Gr-1) from day 11 pi mice, were analyzed by WB for VEGF-A (upper panel), sVR-1 (middle panel). Figure is a representative of two experiments and each experiment represent at least 3 corneas. (F) Relative fold change in the expression of VEGF-A and MMP-9 mRNA in neutrophil depleted and isotype antibody treated mice at day 11 pi as compared to naïve mock infected mice. Figure is a representative of two experiments and each experiment represent at least 4 corneas. Ly6G+ neutrophils were sorted from day 11 pi corneas. Cell suspension from 6–8 pooled corneas was used for neutrophil purification. Purified neutrophils were analyzed by either WB or RTPCR for the expression of VEGF-A. (G) Reducing WB analysis for VEGF-A from two different samples S1- Sample 1 and S2-Sample 2 shows the presence of VEGF-A protein from purified neutrophil samples. Data represent two different experiments and each sample represent neutrophils from 6–8 corneas. (H) Agarose gel analysis for β-actin (92bp) (lane 2) and VEGF-A (214bp) (lane 4) of cDNA from purified neutrophils. Lane 1 and 3 are reverse trancriptase negative control for β-actina and VEGF-A respectively. (I) Neutrophil depletion started from day 7 pi and continued until day 13 pi resulted in reduced angiogenesis as well as SK lesion severity. Data are representative of a two independent experiments (n = 8–10 mice/group). P = 0.0131 (*), P = 0.0068 (**).

To show the influence of neutrophils during HSV-1 induced pathological angiogenesis, experiments were done to compare the extent of angiogenesis and differences in expression levels of VEGF-A and sVR-1 in mice depleted of neutrophils compared to controls. Depletion (with anti-Gr1 MAb) was commenced on day 7 pi. As shown in Figure 6I, whereas the extent of angiogenesis and SK lesion severity continued to increase in magnitude in isotype antibody treated animals, by day 15 pi, when the experiment was terminated, the average angiogenic response and SK severity were significantly decreased in animals treated with neutrophil depleting antibody. Although, cell types in inflammatory reaction other than neutrophils can express Gr1, neutrophils are the predominant Gr1+ population in lesion during clinical phase of SK. We interpret Gr-1 depletion experiment where the VEGF-A levels were decreased to mean that neutrophils represent a major source of the VEGF-A that is involved in HSV-1 induced angiogenesis even though a minority of other cell types in inflammatory reaction can also be Gr1+. Taken together these results demonstrate that neutrophils contribute to the severity of the pathological angiogenic response caused by HSV-1 infection. This occurs because neutrophils, can act as one of the sources of VEGF-A as well as the MMP enzymes that degrade sVR-1, the molecule that binds to VEGF-A and inhibit its angiogenic activity.

Discussion

In this report, we investigate mechanisms by which HSV-1 infection of the eye results in neovascularization, an essential step in the pathogenesis of SK, an ocular lesion that impairs and can ablate vision (35). We confirm a previous report (15) that VEGF-A, a principal angiogenic factor, is produced by the normal eye, but is constrained from causing angiogenesis by being bound to a soluble form of one of its cellular receptors. Our results make the novel observation that one consequence of HSV-1 infection is to cause an imbalance in the production of VEGF-A and sVR-1 that impedes its activity. Whereas, the infection up-regulates VEGF-A production, the expression of sVR-1 is inhibited. Moreover, the sVR-1 protein that is made is degraded by the metalloproteinase enzymes MMP-2, -7 and -9 which permits the VEGF-A, initially derived from infected epithelial cells, and later on inflammatory cells, to exert more effective angiogenic activity. Procedures that decrease the breakdown of sVR-1, such as the administration of the MMPi, marimastat, or the provision of exogenous rsVR-1 protein resulted in lessened angiogenesis. Our results support the notion that the binding of sVR-1 to VEGF-A, a so called VEGF-A trap, acts to limit the extent of pathological angiogenesis such as that caused by ocular infection by HSV-1. It is also conceivable that future therapies to control SK could benefit by procedures that influence the production and activity of the sVR-1. Our overall results are summarized in Figure-7, showing how HSV-1 infection leads to corneal angiogenesis.

Figure 7. Scheme illustrating the mechanism for HSV-1 mediated corneal angiogenesis.

Normal uninfected cornea constitutively secretes large amount of sVR-1 and small amounts of VEGF-A. sVR-1 constrains the physiological effect of VEGF-A by binding it with very high affinity (Left panel). Early after corneal HSV-1 infection, there is sudden increase in the levels of VEGF-A primarily being produced by infected or nearby uninfected corneal epithelial cells. However, levels of sVR-1 go down mainly due to decreased production of sVR-1 by corneal epithelial cells and also due to degradation by MMP-2, MMP7 and MMP9. This in turns leads to more physiologically active VEGF-A, which is now free from inhibitory effect of sVR-1. This active form of VEGF-A drives the initial angiogenic sprouting early after HSV infection (middle panel). During chronic phase of HSK, when HSV-1 is no longer detected in the cornea, inflammatory cells particularly neutrophils act as a source of VEGF-A and different MMPs. This second wave of VEGF-A and MMPs further maintains the angiogenic response by continuous supply of active form of VEGF-A and MMPs, which degrades sVR-1. The development of new leaky blood vessels leads to the release of more plasma and inflammatory cells in the cornea thus setting the stage for chronic SK and blindness (Left Panel).

The pathogenesis of SK involves multiple events that include neovascularization of the normally transparent tissue anterior to the retina. Thus any new blood vessel development in the anterior tissues damages vision by defracting light and, since new vessels are leaky (4, 11), they readily permit escape of inflammatory cells that further contribute to the loss of transparency. Accordingly, preventing, and ideally reversing, neovascularization is an important objective to retain optimal vision. Numerous mechanisms have been suggested to explain how HSV infection could cause neovascularization (8, 28, 36), but perhaps the most important is the induction of VEGF family members, especially VEGF-A which stimulates corneal angiogenesis by engaging the receptor VEGFR-2 (8, 10). Supporting this, prior studies have shown that counteracting the VEGF-A made or inhibiting its receptor can significantly reduce HSV induced angiogenesis (8, 10). Others, as well as ourselves, have already reported that HSV infection of the corneal epithelium in the early stages of keratitis results in the expression of VEGF-A protein either in infected or nearby cells (13, 14). What we had not appreciated, until the observations of the Ambati group appeared (15), is that VEGF-A is continually produced by uninfected normal eyes but fails to cause corneal vascularization because the VEGF-A is bound to a soluble form of one of its receptors (15). The important aspect of our study is our observations that the binding of sVR-1 to VEGF-A made during a pathological disease process may also act to modulate VEGF-A activity and influence the magnitude of angiogenesis. A series of observations led to this conclusion.

Firstly in the early stages after HSV infection much of the VEGF-A detected by WB under native conditions was of a molecular size consistent to its being bound to another protein that was shown to be sVR-1. Of interest, soon after infection one consequence of HSV-1 was to exert a differential effect on gene expression of VEGF-A and sVR-1 proteins. Accordingly, whereas infection caused an increased expression of VEGF-A, the production of the sVR-1 was inhibited. Additionally, that infection of cells could enhance VEGF-A, but suppress sVR-1, gene expression could also be shown by in vitro studies. Thus the initial angiogenesis observed after infection could be the consequence of enhanced VEGF-A activity arising both from increased production as well as diminished inhibition. In support of the latter mechanism, if an additional exogenous source of sVR-1 was provided during the early stages of the disease process, the outcome was diminished angiogenesis. These observations taken together support the idea that a VEGF-A trap operates to limit the extent of pathological angiogenesis at least early after infection.

It is characteristic of HSV-1 ocular infection in the mouse model that the virus is cleared within a few days, but the extent of angiogenesis continues to advance as does the chronic inflammatory process in the corneal stroma that is indicative of SK (4, 8). Our studies show that VEGF-A may also be responsible for the additional angiogenesis but the principal cell source of the VEGF-A is no longer the epithelium (that is no longer infected) but instead derives from invading inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils. We could show that depleting Gr1+ cells with specific mAb on day 7 pi diminished the extent of the neovascular response compared to non-depleted controls indicating their role in VEGF-A production. Depleted animals also had less VEGF-A protein in corneal extracts when quantified by ELISA. However, we anticipated that at the later phases of the disease process, the activity of VEGF-A was less likely to be impeded by its binding to the sVR-1 protein. Thus, in addition to being a source of VEGF-A the invading inflammatory cells are well known to produce many different MMP enzymes (28, 37) some of which could degrade proteins that bind to VEGF-A and limit its activity (34). For example, in some cancer systems where VEGF-A is shown to be bound to a matrix protein, MMP-9 may degrade the matrix protein so releasing VEGF-A to exert angiogenic activity (38). Moreover, VEGF-A processed by different MMPs retains biological activity (39). Also of relevance, MMP-7 was shown very recently to degrade human sVR-1 resulting in increased angiogenic activity in an in vitro tube formation assay using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (19). In our present study, we could demonstrate that the inflammatory exudate cells could express several MMPs and that at least two of them (MMP-7 and MMP-9) were highly effective in vitro at degrading the mouse sVR-1 protein, that had not previously been reported. We could show the effect using a recombinant sVR-1 protein as well as with sVR-1 preparations isolated from normal mouse corneas. However, of special relevance to our viewpoint as the constraining role of sVR-1 on VEGF-A activity, we could clearly demonstrate that if we treated animals with marimastat, an inhibitor of MMP enzyme activity, then the extent of the neovascular response was significantly diminished compared to untreated animals. Furthermore, WB revealed that sVR-1 protein concentrations were higher in marimastat treated corneal samples.

Taken together we contend that our studies have provided novel insight on mechanistic aspects of SK pathogenesis and have revealed a previously unrecognized event that could be targeted for therapeutic manipulation. Accordingly, we show that the important event of ocular angiogenesis mediated by VEGF-A is markedly influenced by the presence and activity of the sVR-1 protein. When bound to sVR-1, as occurs with all of the VEGF-A made by the normal cornea, VEGF-A is unable to mediate angiogenesis. In a pathological situation this VEGF-A trap is also occurring, but it breaks down when levels of MMPs arrive that can degrade the sVR-1 protein (Fig 7). It would seem logical to develop therapies to manage SK that either increase the concentration or retard the breakdown of the sVR-1 protein. Further studies are underway to investigate this issue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Dunlop for his assistance on confocal microscopy. We also thank Naveen Rajasagi, Tamara Veiga Parga and Greg Spencer for their invaluable assistance during manuscript preparation in many ways.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant AI 063365 and National Institutes of Health Grant EY 005093.

References

- 1.Azar DT. Corneal angiogenic privilege: angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in corneal avascularity, vasculogenesis, and wound healing (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:264–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang JH, Gabiso EE, Kato T, Azar DT. Corneal neovascularization. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:242–249. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200108000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deshpande SP, Lee S, Zheng M, Song B, Knipe D, Kapp JA, Rouse BT. Herpes simplex virus-induced keratitis: evaluation of the role of molecular mimicry in lesion pathogenesis. J Virol. 2001;75:3077–3088. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3077-3088.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas PS, Rouse BT. Early events in HSV keratitis--setting the stage for a blinding disease. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell RG, Nasisse MP, Larsen HS, Rouse BT. Role of T-lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of herpetic stromal keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:938–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarangi PS, Rouse BT. Herpetic Keratitis. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, editors. Ocular disease mechanisms and management. Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2010. pp. 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao ZS, Granucci F, Yeh L, Schaffer PA, Cantor H. Molecular mimicry by herpes simplex virus-type 1: autoimmune disease after viral infection. Science. 1998;279:1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng M, Deshpande S, Lee S, Ferrara N, Rouse BT. Contribution of vascular endothelial growth factor in the neovascularization process during the pathogenesis of herpetic stromal keratitis. J Virol. 2001;75:9828–9835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9828-9835.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim B, Tang Q, Biswas PS, Xu J, Schiffelers RM, Xie FY, Ansari AM, Scaria PV, Woodle MC, Lu P, et al. Inhibition of ocular angiogenesis by siRNA targeting vascular endothelial growth factor pathway genes: therapeutic strategy for herpetic stromal keratitis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:2177–2185. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63267-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim B, Suvas S, Sarangi PP, Lee S, Reisfeld RA, Rouse BT. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-based DNA immunization delays development of herpetic stromal keratitis by antiangiogenic effects. J Immunol. 2006;177:4122–4131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagy JA, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. VEGF-A and the induction of pathological angiogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:251–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.134925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCounter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biswas PS, Banerjee K, Kinchington PR, Rouse BT. Involvement of IL-6 in the paracrine production of VEGF in ocular HSV-1 infection. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wuest TR, Carr DJ. VEGF-A expression by HSV-1-infected cells drives corneal lymphangiogenesis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:101–115. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambati BK, Nozaki M, Singh N, Takeda A, Jain PD, Suthar T, Albuquenrque RJ, Richter E, Sakurai E, Newcomb MT, et al. Corneal avascularity is due to soluble VEGF receptor-1. Nature. 2006;443:993–997. doi: 10.1038/nature05249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan T, Hanson I, Zaletayev D, Hodgson S, Prosser J, Seawright A, Hastie N, van Heyningen V. The human PAX6 gene is mutated in two patients with aniridia. Nat Genet. 1992;1:328–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dana MR, Zhu SN, Yamada J. Topical modulation of interleukin-1 activity in corneal neovascularization. Cornea. 1998;17:403–409. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenton RR, Molesworth-Kenyon S, Oakes JE, Lausch RN. Linkage of IL-6 with neutrophil chemoattractant expression in virus-induced ocular inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:737–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito TK, Ishii G, Saito S, Yano K, Hoshino A, Suzuki T, Ochiai A. Degradation of soluble VEGF receptor-1 by MMP-7 allows VEGF access to endothelial cells. Blood. 2009;113:2363–2369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall RL, Thomas KA. Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10705–10709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman CK, Kendall RL, Cabrera G, Soroceanu L, Heike Y, Gillespie GY, Siegal GP, Mao X, Bett AJ, Huckle WR, et al. Paracrine expression of a native soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibits tumor growth, metastasis, and mortality rate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8795–9000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas J, Gangappa S, Kanangat S, Rouse BT. On the essential involvement of neutrophils in the immunopathologic disease: herpetic stromal keratitis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1383–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenwick ML, Clark J. Early and delayed shut-off of host protein synthesis in cells infected with herpes simplex virus. J Gen Virol. 1982;61:121–125. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-61-1-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenwick ML, Walker MJ. Suppression of the synthesis of cellular macromolecules by herpes simplex virus. J Gen Virol. 1978;41:37–51. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-41-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanangat SJ, Babu S, Knipe DM, Rouse BT. HSV-1-mediated modulation of cytokine gene expression in a permissive cell line: selective upregulation of IL-6 gene expression. Virology. 1996;219:295–300. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paludan SR. Requirements for the induction of interleukin-6 by herpes simplex virus-infected leukocytes. J Virol. 2001;75:8008–8015. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8008-8015.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebrahem Q, Chaurasia SS, Vasanji A, Qi JH, Klenotic PA, Cutler A, Asosingh K, Erzurum S, Apte BA. Cross-Talk between Vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases in the induction of Neovascularization in Vivo. Am J Patho. 2010;176:496–503. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.080642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Zheng M, Kim B, Rouse BT. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in angiogenesis caused by ocular infection with herpes simplex virus. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1105–1111. doi: 10.1172/JCI15755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watson SA, Morris TM, Collins HM, Bawden LJ, Hawkins K, Bone EA. Inhibition of tumour growth by marimastat in a human xenograft model of gastric cancer: relationship with levels of circulating CEA. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:19–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada N, Otani Y, Kubota T, Kimata M, Minagawa A, Yoshimizu N, Kameyama K, Saikawa Y, Yoshida M, Furukawa T, et al. Reduced angiogenesis in peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer through gelatinase inhibition. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:431–435. doi: 10.1023/a:1025453500148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimata M, Otani Y, Kubota T, Igarashi N, Yokoyama T, Wada N, Yoshimizu N, Fuzii M, Kameyama K, Okada Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, marimastat, decreases peritoneal spread of gastric carcinoma in nude mice. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:834–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanhan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12493–12498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong Y, Koh DR. Neutrophils promote inflammatory angiogenesis via release of preformed VEGF in an in vivo corneal model. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:437–448. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ardi VC, Kupriyanova TA, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Human neutrophils uniquely release TIMP-free MMP-9 to provide a potent catalytic stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20262–20267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706438104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streilein JW, Dana MR, Ksander BR. Immunity causing blindness: five different paths to herpes stromal keratitis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:443–449. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee K, Biswas PS, Kim B, Lee S, Rouse BT. CXCR2−/− mice show enhanced susceptibility to herpetic stromal keratitis: a role for IL-6-induced neovascularization. J Immunol. 2004;172:1237–1245. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claesson R, Johansson A, Bebasakis G, Hanstrom L, Kalfas S. Release and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 8 from human neutrophils triggered by the leukotoxin of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:353–359. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawinkels LJ, Zuidwijk K, Verspaget HW, de Jonge-Juller ES, van Duijn W, Ferreira V, Fontijn RD, David G, Hommes DW, Lamers CB, et al. VEGF release by MMP-9 mediated heparan sulphate cleavage induces colorectal cancer angiogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1904–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:681–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.