Abstract

Introduction

Post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is a common complication after partial pancreatic resection, and is associated with increased rates of sepsis, mortality and costs. The role of fibrin sealants in decreasing the risk of POPF remains debatable. The aim of this study was to evaluate the literature regarding the effectiveness of fibrin sealants in pancreatic surgery.

Methods

A comprehensive database search was conducted. Only randomized controlled trials comparing fibrin sealants with standard care were included. A meta-analysis regarding POPF, intra-abdominal collections, post-operative haemorrhage, pancreatitis and wound infections was performed according to the recommendations of the Cochrane collaboration.

Results

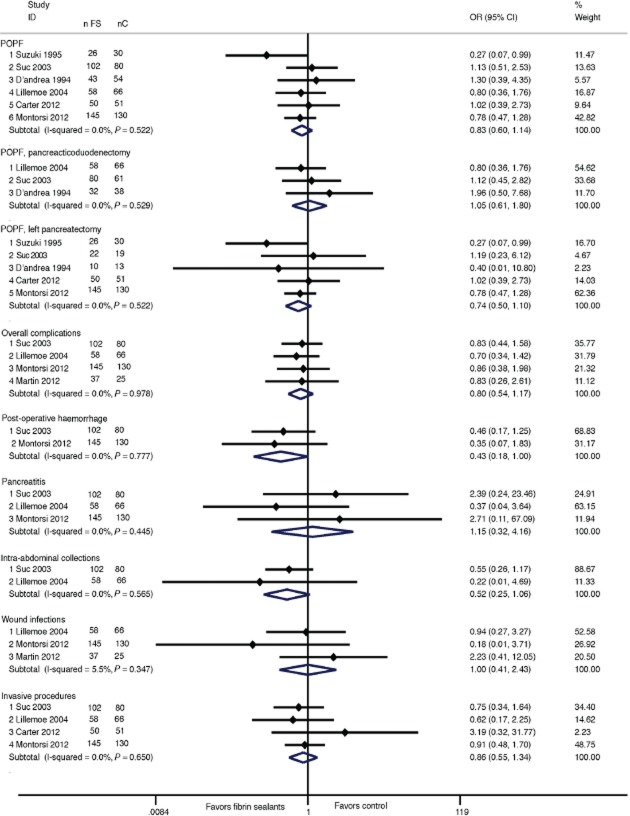

Seven studies were included, accounting for 897 patients. Compared with controls, patients receiving fibrin sealants had a pooled odds ratio (OR) of developing a POPF of 0.83 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.6–1.14], P = 0.245. There was a trend towards a reduction in post-operative haemorrhage (OR = 0.43 (95%CI: 0.18–1.0), P = 0.05) and intra-abdominal collections (OR = 0.52 (95%CI: 0.25–1.06), P = 0.073) in those patients receiving fibrin sealants. No difference was observed in terms of mortality, wound infections, re-interventions or hospital stay.

Conclusion

On the basis of these results, fibrin sealants cannot be recommended for routine clinical use in the setting of pancreatic resection.

Introduction

Pancreatic resection represents a major surgical procedure, and although peri-operative mortality has been reduced to below 5% in most centres, post-operative morbidity remains high, with 30–60% of patients experiencing complications.1,2 Post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is a commonly feared complication for hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgeons, owing to its association with increased mortality, sepsis, hospital stay and costs.3 The incidence of POPF after pancreatico-duodenectomy (PD) varies in different series, lying between 5% and 35%.4,5 The POPF rate after left pancreatectomy (LP) ranges from 13% to 64%.6

Several strategies have been proposed in order to prevent POPF formation, including peri-operative administration of somatostatin analogues,4,5 pancreaticogastrostomy instead of pancreaticojejunostomy7 and hand-sutured versus stapler closure of the pancreatic remnant after LP.6 Fibrin sealants are a group of therapeutic agents with several indications, such as helping to achieve improved local haemostatic control, reinforcing suture lines and stimulating wound healing.8 Although there are several commercialized formulae, with variations in their precise composition, fibrin sealants all share the common feature of combining fibrinogen and thrombin, in order to mimic the final step of physiological haemostasis.8 The effectiveness of fibrin sealants has been evaluated in several surgical settings, including liver,9,10 hernia,11 orthopaedic,12 urological,13 cardiac14 and breast surgery,15 with conflicting results.

In the setting of pancreatic resection, there are a number of previous retrospective and non-randomized studies that have assessed the role of fibrin sealants in decreasing the POPF rate.16–19 However, considering the high cost of fibrin sealants, there is a need for quality evidence regarding their use in daily clinical practice. To clarify this issue, it was decided to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effect of fibrin sealants on the incidence of POPF and other complications for patients undergoing pancreatic surgery.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

The present methodology is in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).20

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Register of clinical trials (CENTER) were searched from 1966 onwards. The following search terms were combined in MEDLINE: ((fibrin seal[MeSH Terms]) OR (fibrin sealant[MeSH Terms]) OR (fibrin sealant system[MeSH Terms]) OR (adhesive, fibrin tissue[MeSH Terms]) OR (fibrin sealant, human[MeSH Terms]) OR (human fibrin sealant[MeSH Terms]) OR (fibrin glue[MeSH Terms]) OR (tissucol[MeSH Terms]) OR (tisseel[MeSH Terms]) OR (tachosil) OR (vitagel) OR (beriplast) OR (biocol) OR (biostat) OR (tachocomb) OR (quixil) OR (evicel) OR (fibrin glue sealing) OR (artiss) AND ((pancreaticoduodenectomy[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreaticojejunostomy[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreaticoduodenectomies[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreaticojejunostomies[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreatic duct[MeSH Terms]) OR (anastomotic leak[MeSH Terms]) OR (leak, anastomotic[MeSH Terms]) OR (leakage, anastomotic[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreatic fistula[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreatic fistulas[MeSH Terms]) OR (fistula) OR (fistulae) OR (postoperative complications[MeSH Terms]) OR (pancreatic remnant) OR (pancreatic stump) OR (pancreatic surgery) OR (pancreas surgery)). An equivalent query was formulated in EMBASE and CENTER.

Inclusion criteria were: RCTs comparing the application fibrin sealants with placebo (or no drug) for adult patients undergoing pancreatic resection. Patients treated with both PD and LP were included. There was no inclusion limit regarding the various commercially available fibrin sealant preparation, date of publication, language or publication status.

Data collection

Two authors extracted data, and disagreements were resolved by reaching a consensus with the remaining authors. Demographic and clinical variables of interest were as follows: age, gender, indication for pancreatic resection and type of surgical procedure. The fibrin sealant preparation price was systematically collected (as reported in the included studies or according to the manufacturer product information). The primary outcome was overall incidence of POPF. The severity of the POPF was graded according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) definition.21 Secondary outcomes included the impact of the POPF on the post-operative course (according to the ISGPF grading system), overall complications (including POPF), sepsis, delayed gastric emptying, post-operative haemorrhage (digestive or intra-abdominal), acute pancreatitis, intra-abdominal collections (infected or not) as diagnosed by a computed tomography scan, wound infection, necessary invasive procedures (reoperation or interventional radiology), 30-day mortality and mean length of hospital stay. The included studies were critically appraised evaluating the quality of reporting of important methodological components. The Jadad score,22 which ranks the quality of RCTs on a five-points scale according to randomization, blinding and attrition, was also used.

Statistical analysis

When the included trials were deemed comparable, their results were pooled in several meta-analyses. Binary outcomes were combined as pooled odds ratio (OR), and for continuous outcomes, the weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported. The number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated as the inverse of the difference between the control and intervention group event rate. In studies which reported the median only, the median was either pooled in the meta-analysis assuming normal distribution or converted to the mean according to previously detailed methodology.23 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Q-test with a significance level set at P = 0.05. To quantify heterogeneity, the I2 measure was used. Data were pooled applying either the fixed (inverse variance) or random effect model.24 In case of heterogeneity or marked clinical variability, it was planned to perform sensitivity analyses. Separate analyses of populations undergoing PD or LP were performed. Looking for a consistent POPF definition, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken retaining only those trials using the ISGPF definition.21 Lastly, because surgical technique and the skills of the surgeon are considered to have an impact on the risk of POPF,25 separate analyses for different surgical techniques (pancreaticojejunostomy or pancreaticogastrostomy, hand-sewn or stapled closure of the pancreatic stump in LP) were carried out. A funnel plot was used to assess publication bias, as explained in the illustration. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12®, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA. Statistical significance was set at the P < 0.05 level.

Results

Literature search and characteristics of the included studies

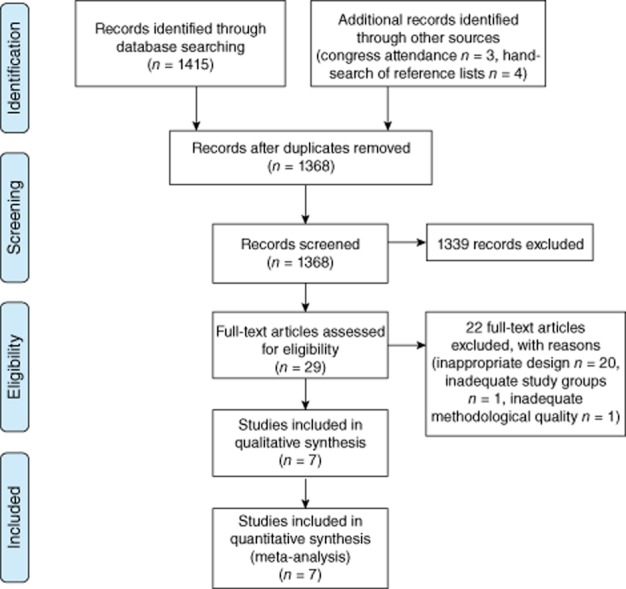

The literature search identified 1415 articles. Hand searching the reference list of retrieved articles and congress attendance allowed identification of seven additional trials. Two studies were identified before publication.26,27 A majority of articles were excluded because of irrelevant subject based on abstract reading. Twenty-nine studies were scrutinized. Twenty non-randomized controlled studies were further excluded, as well as two RCTs: one because the intervention groups were not suitable for inclusion (pancreaticojejunostomy versus no anastomosis and pancreatic duct occlusion),28 and another because its methodology was severely flawed (part of the data were collected retrospectively).29 Seven RCTs fulfilling the inclusion criteria were retained.26,27,30–34 The PRISMA flow diagram of the inclusion–exclusion process is depicted in Fig. 1. Publication dates ranged from 199431 to 2012.26,27,30 Two trials were held in the United States30,32 and Italy,27,31 and one, respectively, in Australia,26 Japan34 and France.33 Overall, 897 patients were included (461 in the fibrin sealant group and 436 in the control group). Three trials included patients undergoing LP only,27,30,34 two focused on PD26,32 and the remaining two studies included patients regardless of the site of pancreatic resection.31,33 Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included trials.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the inclusion/exclusion process

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Country | n | Surgical procedure | POPF definition | Jadad score | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| D'Andrea 199431 | Italy | 43 | 54 | PD (n = 70), LP (n = 23), tumour excision (n = 4) | Radiological assessment | 2 | |

| Suzuki 199534 | Japan | 26 | 30 | LP | >7-day long discharge of an amylase-rich drain fluid (≥threefold elevation above the level of serum) | 2 | |

| Suc 200333 | France | 102 | 80 | PD (n = 141), LP (n = 41) | ≥3 day-long discharge of an amylase-rich drain fluid (>fourfold elevation above the level of serum) and/or radiological assessment | 5 | Compared to controls, patients in the intervention group received more prophylactic sandostatin analogues |

| Lillemoe 200432 | USA | 58 | 66 | PD | ≥10 days discharge of an amylase-rich drain fluid (>threefold elevation above the level of serum) | 3 | Soft glands only |

| Carter 201230 | USA | 50 | 51 | LP | ISGPF criteria | 5 | Soft glands only |

| Montorsi 201227 | Italy | 145 | 130 | LP | ISGPF criteria | 2 | |

| Martin 201226 | Australia | 37 | 25 | PD | ISGPFcriteria | 2 | In the intervention group, all anastomoses (pancreatico-jejunostomy, choledoco-jejunostom and entero-enteral anastomosis) were covered with fibrin sealant. |

POPF, post-operative pancreatic fistula; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; LP, left pancreatectomy; ISGPF, International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula.

Critical appraisal

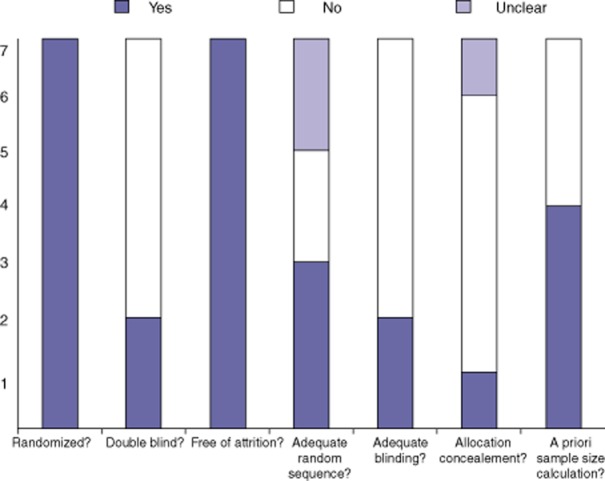

The reporting of important methodological components is summarized in Fig. 2. According to the Jadad score, two30,33 trials were of high methodological quality. The other five trials were of intermediate (Jadad score = 3),32 and moderate to low (Jadad score ≤2)26,27,31,34 quality. When considering other sources of bias, the study by Suc et al.33 had noticeable baseline imbalances between study groups, as there were significantly more patients in the fibrin sealant group receiving somatostatin analogue prophylaxis and more pancreatic parenchyma described as non-fibrous in the control group. Two studies included only patients with a high-risk (soft) pancreatic parenchyma.30,32 Of note, Carter et al. excluded eight (7%) patients with a hard parenchyma after randomization.30 There were more men in the fibrin sealant group in one study.27 Two studies were prematurely interrupted before reaching the a priori determined sample size, and although the reason for trial interruption was clearly stated (futility of detecting a difference following interim statistical analysis), these trials were at a higher risk of a type II statistical error.30,32 Regarding between-study comparability, three trials were published after 2005 and used the ISGPF fistula definition.26,27,30 Two studies used a similar definition of POPF (prolonged discharge with an amylase concentration at least three times more elevated in the fluid of drainage compared with the serum level) on day 7 and 10,32,34 respectively. Suc et al.33 considered a POPF as a 3-days consecutive discharge with a fourfold increase in amylase. D'Andrea et al. considered only radiologically-proven fistulae.31 A funnel plot showed no obvious asymmetry (Supplementary material).

Figure 2.

Methodological appraisal

Description of the intervention

All the included studies compared fibrin sealants versus no intervention. In addition to fibrin glue application, Carter et al.30 used a falciform ligament patch sutured over the pancreatic stump. One trial applied fibrin glue inside the main pancreatic duct.33 In the remaining studies, the fibrin sealant was applied on the pancreaticojejunostomy or, in case of LP, on the suture or staple line of the pancreatic stump. In the fibrin sealant group of the study by Martin et al.,26 Tisseel® was applied to all anastomoses (not only pancreaticojejunostomy) tailored during a PD. A part from one study that assessed the role of a fibrin sealant patch,27 all trials applied fibrin in a gelatinous form. The weighted mean (± standard deviation) price of fibrin sealant was $275 (± 128) per unit. The various commercially available preparations used in the included trials are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of fibrin sealant preparation used in the included studies

| D'Andrea 199431 | Suzuki 199534 | Suc 200333 | Lillemoe 200432 | Carter 201230 | Montorsi 201227 | Martin 201226 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial name | Unknown | Tissucol/Tisseel® | Tissucol/tisseel® | Hemaseel APR® | Vitagel® | TachoSil® patch | Tissucol/Tisseel® |

| Fibrinogen | Human-derived Unknown concentration | Human-derived 90 mg/ml | Human-derived 90 mg/ml | Human-derived 75–115 mg/ml | Autologous plasma | Human-derived 5.5 mg/cm2 | Human-derived 90 mg/ml |

| Factor XIII | None | 10–50 kIU/ml | 10–50 kIU/ml | None | None | None | 10–50 kIU/ml |

| Thrombin | Unknown origin | Human-derived 500 IU/ml | Human-derived 500 IU/ml | Human derived 500 IU/ml | Bovine-derived 300 UI/ml | Human-derived 2 IU/cm2 | Human-derived 500 IU/ml |

| Aprotinin | Bovine-derived 5 000–20 000 kIU/ml | Bovine-derived 3 000 kIU/ml | Bovine-derived 30 000 kIU/ml (added separately to the preparation) | Bovine-derived 3000 kIU/ml | None | None | Bovine-derived 3000 kIU/ml |

| Price | Unknown | $160b | $160b | $164a | $470a | $395a | $160b |

Price as reported in the individual studies or

as estimated according to manufacturer product information. (http://www.ecomm.baxter.com). Currency conversion rates were calculated on 20 December 2012 (http://www.ecomm.baxter.com/ecatalog)

Effect of intervention

Primary outcome

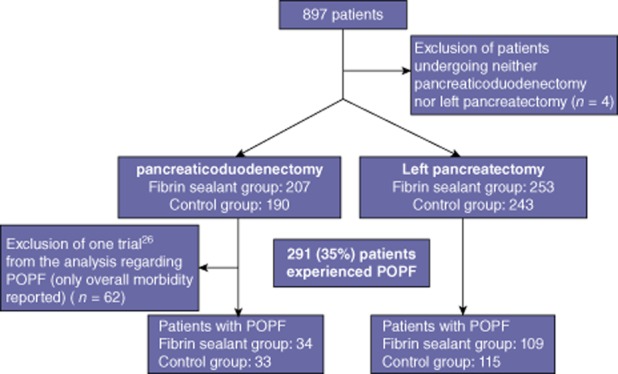

The outputs of the meta-analysis are depicted in Fig. 3. Six trials reported POPF incidence.27,30–34 Overall, regardless of group allocation, 291 patients (35%) were diagnosed with a POPF. In PD and LP, the pooled incidence rate of POPF was 20% (n = 67) and 45% (n = 224), respectively (Fig. 4). The highest rate was observed in LP studies applying the ISGPF definition27,30 (52.6%, n = 198). Compared with controls, patients receiving fibrin sealants had a pooled OR of experiencing POPF of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.6–1.14), P = 0.245, I2 = 0%, fixed effect model). In the two LP trials reporting the ISGPF-defined severity of a POPF,27,30 the effect of fibrin sealants appeared to be more marked in the setting of severe POPF [grade A: OR = 0.97 (95% CI: 0.61–1.55), P = 0.895, grade B: OR = 0.84 (95% CI: 0.43–1.62), P = 0.597 and grade C: OR = 0.31 (95% CI: 0.06–1.52), P = 0.148, respectively].

Figure 3.

Forest plot depicting the results of the meta-analysis, fixed-effect model. The vertical line shows the null hypothesis (OR = 1). Odds ratio (OR), post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF), confidence interval (CI), nFS (number of patients in the fibrin sealant group), nC (number of patients in the control group)

Figure 4.

Diagram of the incidence of a post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF)

Secondary outcomes

The incidence of overall complications was reported in four trials,26,27,32,33 showing similar results in both groups (OR = 0.8 (95% CI: 0.54–1.17), P = 0.249). There was borderline evidence supporting that, compared with controls, patients treated with fibrin sealants were 57% less likely to experience post-operative haemorrhage [OR = 0.43 (95% CI: 0.18–1.0), P = 0.05, NNT = 24]. A statistical trend favouring fibrin sealants was observed when considering the incidence of intra-abdominal collection [OR = 0.52 (95% CI: 0.25–1.06), P = 0.073, NNT = 15]. There was no difference regarding acute pancreatitis (P = 0.828), invasive procedures (P = 0.512), wound infection (P = 1) or death (P = 0.504) (see Fig. 3). The length of hospital stay was not significantly shortened after fibrin sealant use [WMD = –0.915 days (95% CI: −2.51 to 0.68), P = 0.262, I2 = 0%, fixed effect model]. No trials reported thrombo-embolic events or allergic reactions.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

A subgroup analysis was performed in order to take the surgical procedure (PD or LP) into account. There was no evidence of a difference in the POPF incidence in either PD [OR = 1.05 (95% CI: 0.61–1.8), P = 0.873] or LP [OR = 0.74 (95% CI: 0.5 −1.1), P = 0.140]. When analysing only trials with adequate methodology (Jadad score ≥3), the pooled OR was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.6–1.58), P = 0.896. After exclusion of trials not applying the ISGPF definition, the pooled OR was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.53–1.29), P = 0.397. In a sensitivity analysis of trials using a fibrin sealant preparation containing aprotinin, the OR was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.52–1.32), P = 0.425. No difference was observed after restricting the analysis to patients described as having a soft pancreatic parenchyma (OR = 0.88 (95% CI: 0.48–1.63), P = 0.691). When analysing only trials performing hand-sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant,31,34 the OR was 0.29 (95% CI: 0.09–0.96), P = 0.042, random effect model. Because trials assessing the role of fibrin sealants in PD had liberal policies regarding pancreatico-digestive anastomosis (end-to-end or end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy, pancreaticogastrostomy, pylorus-preservation or not, stent placement), neither sensitivity nor subgroup analyses were feasible in this matter.

Discussion

The idea of applying topical fibrin as a means of improving local haemostasis and enhancing wound healing was already reported more than a century ago.35 Although there is abundant literature assessing the role of fibrin sealants in surgical settings such as orthopaedics,12 liver9,10 and cardiovascular14 surgery, their effectiveness in pancreatic surgery remains scarce and inconclusive. Accordingly, this systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed at gathering, analysing and critically appraising the best available evidence on the effectiveness of fibrin sealant products at reducing fistula formation after pancreatic resection.

Overall, one-third of the included patients experienced POPF, consistent with the literature.36–38 A twofold higher risk of developing POPF was observed in patients undergoing LP (45%) compared with PD (20%). This risk was even higher when the ISGPF criteria were applied (52.6%), illustrating the fact that the ISGPF identifies an important number of fistulae, including those with little clinical relevance. The current study does not support the routine clinical use of fibrin sealants in pancreatic surgery, as their use is not associated with a significant reduction in POPF, overall complications or length of hospital stay. In contrast, there was some evidence for a markedly lower incidence (57%) of post-operative bleeding events (OR = 0.43 95% CI: 0.18–1.0 P = 0.05) after fibrin sealant use. This finding is in agreement with other surgical studies reporting a reduced blood loss in patients receiving fibrin sealants.12,39–43 Besides technical failures such as non-haemostatic suture lines or slipping ligatures, bleeding events after pancreatic resection are usually related to vascular erosions caused by a pancreatic leak.44 It could be argued that the lower risk of haemorrhage in the fibrin sealant group constitutes a surrogate marker of a decreased POPF rate. However, because only one trial27 separately reported early and late complications, it was not possible to perform a subgroup analysis focusing on delayed bleeding events. Therefore, this assumption must be interpreted with caution. The result of a 48% reduction in intra-abdominal collections approached statistical significance (P = 0.073), representing weak evidence of the effectiveness of fibrin sealants on a common complication after a pancreatic resection.

Aiming at distinguishing between overall and clinically relevant fistula, a sensitivity analysis of trials grading the severity of the observed fistula according to the ISGPF criteria27,30 was conducted. Although not significant, it appeared that the magnitude of effect attributed to the intervention increased along with the severity of POPF, as patients receiving fibrin sealants experienced a 3% (P = 0.895), 16% (P = 0. 597) and 69% (P = 0.148) lower risk of POPF grade A, B, and C, respectively. Additionally, it could be argued that among the fistulae reported as an overall incidence rate and not graded according to severity,31–34 some must have been truly clinically relevant. Because these could not be analysed separately, the power of the sensitivity analysis was reduced.

Although statistical heterogeneity did not hamper the meta-analyses reported herein, there was some degree of between-study clinical variability. Several factors contributed to this. First, early studies had various criteria for defining POPF, making them less comparable in terms of POPF incidence rate. Hence, it was decided to analyse separately the results of studies applying the ISPGF definition, as well as performing a meta-analysis of the ISGPF-defined severity of POPF. This strategy did not reveal a significant difference in the POPF incidence nor interaction caused by severity grade, consistent with the null hypothesis that there is no effect of fibrin sealants on POPF. Second, one could question the meaningfulness of pooling the results of studies held in the settings of PD and LP in a unique meta-analysis. Thus, subgroup analyses of patients undergoing either PD or LP were performed. Both of these analyses were statistically insignificant. Third, although all fibrin sealants used in the included studies are mainly composed of fibrinogen and thrombin, their precise composition varies noticeably. For instance, aprotinin, which was used in all but two trials, is an antiprotease molecule that could be useful in preventing early degradation of fibrinogen by pancreatic proteolytic enzymes. However, performing sensitivity analyses of fibrin sealants with and without aprotinin did not affect the results.

Looking at the potential confounding introduced by variability in the surgical technique, a sensitivity analysis was performed, retaining only those procedures31,34 where the pancreatic stump was hand-sewn. This analysis revealed a statistically significant 71% lower risk of a POPF for patients receiving fibrin sealants compared with controls, suggesting that fibrin sealants could be more beneficial in the setting of manual closure of the transected parenchyma. Notwithstanding the surgical technique, the trials by D'Andrea et al.31 and Suzuki et al.34 were also of low methodological quality, limiting the generalizability of this finding.

The trials included herein were of heterogenous quality. Two trials had a high Jadad score,30,33 but two others used a questionable random sequence generation method (flip a coin,26 or drawing of lots34). Only one trial reported adequate allocation concealment,30 and blinding of outcomes assessors was described in three studies.30,32,33 Thus, the risk of observer bias was high, considering the fact that surgeons might have been biased by their awareness of allocation in their diagnosis of POPF. In addition, selection bias was likely in several situations, owing to the exclusion of patients after randomization30 and the presence of significant baseline imbalance in gender,27 or others acknowledged confounding factors such as prophylactic somatostatin analogues administration.33 Again, restricting the analyses to trials with a more rigorous design revealed no interaction.

Fibrin sealants are expensive devices. On the basis of a weighted mean price of $275 per application, and assuming the use of a single unit per patient, $6600 (NNT = 24) and $4125 (NNT = 15) would be necessary to prevent one patient from experiencing post-operative bleeding and intra-abdominal collection(s), respectively. Of note, these observations rely on the assumption that the use of fibrin sealant is truly associated with a lower risk of bleeding events and intra-abdominal collections. This remains a matter debate, and further studies are warranted.

This is the first meta-analysis evaluating the role of fibrin sealants in pancreatic surgery. The current findings do not provide the evidence to justify routine clinical use of costly interventions such as fibrin sealants in an era of scarce resources, and should lead to further research in the form of additional adequately powered prospective randomized trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Artères foundation. C.T. was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SCORE grant 3232230-126233) and by a Professorship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP00P3_139021).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Funnel plot, post-operative pancreatic fistula data. Odds ratio (OR). Each point illustrates a trial. The solid line depicts the effect size (pooled OR = 0.82). Studies located on the left side of the null hypothesis (Log OR = 0) support the intervention. Asymmetry may suggest publication bias.

References

- 1.Buchler MW, Wagner M, Schmied BM, Uhl W, Friess H, Z'Graggen K. Changes in morbidity after pancreatic resection: toward the end of completion pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1310–1314. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1310. discussion 1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho CK, Kleeff J, Friess H, Buchler MW. Complications of pancreatic surgery. HPB. 2005;7:99–108. doi: 10.1080/13651820510028936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T, Huang ZS, Callery MP, Vollmer CM., Jr Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg. 2007;245:443–451. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251708.70219.d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gans SL, van Westreenen HL, Kiewiet JJ, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of somatostatin analogues for the treatment of pancreatic fistula. Br J Surg. 2012;99:754–760. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Fusai G, Davidson BR. Somatostatin analogues for pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008370.pub2. CD008370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1514–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKay A, Mackenzie S, Sutherland FR, Bathe OF, Doig C, Dort J, et al. Meta-analysis of pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:929–936. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spotnitz WD. Fibrin sealant: past, present, and future: a brief review. World J Surg. 2010;34:632–634. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer MT, Boonstra EA, Lisman T, Porte RJ. Role of fibrin sealants in liver surgery. Dig Surg. 2012;29:54–61. doi: 10.1159/000335735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figueras J, Llado L, Miro M, Ramos E, Torras J, Fabregat J, et al. Application of fibrin glue sealant after hepatectomy does not seem justified: results of a randomized study in 300 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:536–542. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245846.37046.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong JU, Leung TH, Huang CC, Huang CS. Comparing chronic pain between fibrin sealant and suture fixation for bilayer polypropylene mesh inguinal hernioplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Surg. 2011;202:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy O, Martinowitz U, Oran A, Tauber C, Horoszowski H. The use of fibrin tissue adhesive to reduce blood loss and the need for blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. A prospective, randomized, multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1580–1588. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong YM, Loughlin KR. The use of hemostatic agents and sealants in urology. J Urol. 2006;176:2367–2374. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe J, Luber J, Levitsky S, Hantak E, Montgomery J, Schiestl N, et al. Evaluation of the topical hemostatic efficacy and safety of TISSEEL VH S/D fibrin sealant compared with currently licensed TISSEEL VH in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical study. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;48:323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carless PA, Henry DA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of fibrin sealant to prevent seroma formation after breast cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93:810–819. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chirletti P, Caronna R, Fanello G, Schiratti M, Stagnitti F, Peparini N, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy with application of fibrinogen/thrombin-coated collagen patch (TachoSil) in Roux-en-Y reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1396–1398. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0894-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mita K, Ito H, Fukumoto M, Murabayashi R, Koizumi K, Hayashi T, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy using a fibrin adhesive sealant (TachoComb(registered trademark)) for the prevention of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marangos IP, Rosok BI, Kazaryan AM, Rosseland AR, Edwin B. Effect of TachoSil patch in prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1625–1629. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1584-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satoi S, Toyokawa H, Yanagimoto H, Yamamoto T, Hirooka S, Yui R, et al. Reinforcement of pancreticojejunostomy using polyglycolic acid mesh and fibrin glue sealant. Pancreas. 2011;40:16–20. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f82f55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;2005:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andren-Sandberg A, Wagner M, Tihanyi T, Lofgren P, Friess H. Technical aspects of left-sided pancreatic resection for cancer. Dig Surg. 1999;16:305–312. doi: 10.1159/000018740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin I, Yuen L, Au K. Does fibrin glue sealant decrease the rate of anastomotic leak following pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized trial. HPB. 2012;14(Suppl. 2):13–106. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montorsi M, Zerbi A, Bassi C, Capussotti L, Coppola R, Sacchi M. Efficacy of an Absorbable Fibrin Sealant Patch (TachoSil) After Distal Pancreatectomy: a Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2012;256:853–860. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318272dec0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran K, Van Eijck C, Di Carlo V, Hop WC, Zerbi A, Balzano G, et al. Occlusion of the pancreatic duct versus pancreaticojejunostomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2002;236:422–428. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tashiro S, Murata E, Hiraoka T. New technique for pancreaticojejunostomy using a biological adhesive. Br J Surg. 1987;74:392–394. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carter TI, Fong ZV, Hyslop T, Lavu H, Tan WP, Hardacre J, et al. A Dual-Institution Randomized Controlled Trial of Remnant Closure after Distal Pancreatectomy: does the Addition of a Falciform Patch and Fibrin Glue Improve Outcomes? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:102–109. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1963-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Andrea AA, Costantino V, Sperti C, Pedrazzoli S. Human fibrin sealant in pancreatic surgery: it is useful in preventing fistulas? A prospective randomized study. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1994;26:283–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Kim MP, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, Coleman JA, et al. Does fibrin glue sealant decrease the rate of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:766–772. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suc B, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Fourtanier G, Hay JM, Holmières F, et al. Temporary fibrin glue occlusion of the main pancreatic duct in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications after pancreatic resection: prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2003;237:57–65. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y, Morita A, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Kawamura T, et al. Fibrin glue sealing for the prevention of pancreatic fistulas following distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1995;130:952–955. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430090038015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergel S. Uber Wirkungen des Fibrins. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1909;35:633–665. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuks D, Piessen G, Huet E, Tavernier M, Zerbib P, Michot F, et al. Life-threatening postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade C) after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. Am J Surg. 2009;197:702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frymerman AS, Schuld J, Ziehen P, Kollmar O, Justinger C, Merai M, et al. Impact of postoperative pancreatic fistula on surgical outcome – the need for a classification-driven risk management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Facy O, Chalumeau C, Poussier M, Binquet C, Rat P, Ortega-Deballon P. Diagnosis of postoperative pancreatic fistula. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1072–1075. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belboul A, Dernevik L, Aljassim O, Skrbic B, Râdberg G, Roberts D. The effect of autologous fibrin sealant (Vivostat) on morbidity after pulmonary lobectomy: a prospective randomised, blinded study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:1187–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mawatari M, Higo T, Tsutsumi Y, Shigematsu M, Hotokebuchi T. Effectiveness of autologous fibrin tissue adhesive in reducing postoperative blood loss during total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomised study of 100 cases. J Orthop Surg. 2006;14:117–121. doi: 10.1177/230949900601400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noun R, Elias D, Balladur P, Bismuth H, Parc R, Lasser P, et al. Fibrin glue effectiveness and tolerance after elective liver resection: a randomized trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stutz H, Hempelmann H. The use of autologous fibrin glue to reduce perioperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty – results of a controlled study. Orthopadische Praxis. 2004;40:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molloy DO, Archbold HA, Ogonda L, McConway J, Wilson RK, Beverland DE. Comparison of topical fibrin spray and tranexamic acid on blood loss after total knee replacement: a prospective, randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:306–309. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.17565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, Habermann CR, Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg. 2007;246:269–280. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000262953.77735.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.