Abstract

Objectives

To assess the safety and feasibility and discuss the oncological impact of a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique with a hepatectomy for locally advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Patients and Methods

From 2005 to March 2009, 49 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma underwent a major right-sided hepatectomy with curative intent. Portal vein resection was performed using the no-touch technique in 36 patients (PVR group) but the portal vein was not resected in the other 13 patients (NR group). Peri-operative data and histological findings were compared between the two groups. Moreover, tumour recurrence and survival rates after surgery were calculated and compared for each group.

Results

Although the tumours of the patients in the PVR group were more locally advanced, the residual tumour status and tumour recurrence rate were similar and there was no significant difference in long-term survival between the two groups: 5-year survival rates in the PVR and NR groups were 59% and 51%, respectively (P = 0.353). In-hospital mortality was encountered in 2 of the 49 patients.

Conclusion

A portal vein resection using the no-touch technique with a right-sided hepatectomy had a positive impact on survival and is feasible in terms of long-term outcomes with acceptable mortality.

Introduction

Vascular invasion has been the main cause of the irresectability of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, making surgery for advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma challenging for biliary surgeons. However, advances in surgical techniques during the last several decades have made it possible to resect and reconstruct an involved portal vein with acceptable morbidity and mortality.1–5

In general, resection of the portal vein is carried out when the portal vein is adherent to the tumour and cannot be freed. Although the curative resection rate has been increased owing to en bloc resection of the portal vein, overall survival remains worse in patients who have undergone a portal vein resection than in those who have not.2,3 The procedure may disseminate the cancer cells in the vicinity of the main tumour and worsen the prognoses of patients undergoing a portal vein resection.2,3 To avoid dissemination, the portal vein is routinely resected and reconstructed without any attempts to dissect it when the tumour abuts the portal vein on pre-operative imaging. The surgical outcomes and short-term survival of an aggressive resection, including simultaneous portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, have been reported previously.1,6,7

However, the impact on survival of a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique with a hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma is unclear. The aim of this study was to assess the safety and feasibility and discuss herein the oncological impact of a hepatectomy combined with a no-touch resection of hilar malignancies.

Patients and methods

From 2005 to 2009, 49 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma underwent a major right-sided hepatectomy (hemihepatectomy or trisectionectomy) and biliary reconstruction with curative intent.

A left-sided hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma predominantly involving the left hepatic duct has an anatomic disadvantage in terms of curability and is associated with a significantly worse survival than that in a right hepatectomy.6 Hence, the patients who underwent a left-sided hepatectomy were excluded from the present study.

The future remnant liver volume was routinely evaluated by volumetric analysis and portal vein embolization was performed prior to surgery if necessary.

Pre-operative biliary decompression was performed to reduce the serum bilirubin concentration below 2 mg/dl for all patients with jaundice and to control segmental cholangitis. Single or double endoscopic naso-biliary drainage (ENBD) of the future remnant liver was performed as an initial drainage. Second ENBD catheters were placed to drain biliary trees in the future remnant liver that were not decompressed by the first catheter, or to control cholangitis. Alternatively, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) was employed when drainage by ENBD was not effective or a third catheter was required. The details of their strategy have been reported previously.7

The decision to perform a portal vein resection was made based on pre-operative imaging. When the tumour abutted the portal vein on pre-operative imaging, the portal bifurcation was routinely resected and reconstructed before the hepatic resection without an attempt being made to dissect the portal vein. Portal vein reconstruction was performed in an end-to-end fashion, taking care to avoid torsion and stricturing of the anastomosis. The anastomosis was created with a continuous 5/0 non-absorbable suture, using the intra-luminal suturing technique for the posterior wall and the over-and-over method for the anterior wall. At the end of the operation, portal flow was confirmed by colour Doppler ultrasonography. The details of the procedure for portal vein resection and reconstruction have been described previously.1,6

In the present study, all the hepatectomy procedures performed included caudate lobectomy, extrahepatic bile duct resection, and dissection of lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament and around the pancreatic head. Biliary tract reconstruction was achieved by a bilio-enterostomy using a Roux-en-Y jejunal limb, and external biliary stents were placed through every anastomosis.

A pancreatoduodenectomy was performed for the patients with evidence of an invasive lesion in the intrapancreatic bile duct, based on the results of the pre-operative examination or intra-operative frozen section analysis. Reconstruction during the pancreatoduodenectomy was performed with an end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy using a Child's procedure.

Histological findings were evaluated using the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors by the International Union Against Cancer (7th edition).8 The R0 was defined as the pathologically tumour free status at the radial margin, hepatic and duodenal margin of the resected bile duct and cut surface of the liver.

The peri-operative variables and clinicopathological data from the groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney U-test, χ2 test or Fisher's exact test.

Operative morbidity was defined as all the post-operative complications that lengthened the hospital stay. In-hospital mortality was defined as death within the same hospital admission. Ninety-day mortality was defined as death after discharge from hospital within 90 days.

Patients were followed regularly every 3 months via the outpatient department. Serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were monitored every 3 months. An abdominal computed tomography scan, and/or abdominal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging were performed every 6 months.

When suspicious new lesions emerged and showed progression over several radiological examinations, a diagnosis of recurrence was made. Elevation of tumour markers was adjunctive findings for diagnosis of recurrence.

Post-operative survival rates, including any deaths, and recurrence-free survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences in survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. The statistical software StatFlex ver.6 (Artech Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan) was used for data analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics and surgical outcomes

In 13 of the 49 patients, no resection was performed for the portal bifurcation because the tumour was located distant from the portal vein (NR group). In the remaining 36 patients, a portal vein resection and reconstruction using the no-touch technique (PVR group) was performed. The patients' characteristics and peri-operative variables are shown in Table 1. The peri-operative data from the patients in the PVR group were similar to those in the NR group. Post-operative complications prolonging the hospital stay are presented in Table 2. There were no post-operative complications directly related to PVR and reconstruction.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics and peri-operative variables of the patients in NR and PVR group

| NR (n = 13) | PVR (n = 36) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 68 (58–77) | 68.5 (56–78) | 0.768 |

| Gender (male/female) | 10/3 | 25/11 | 0.731 |

| Pre-operative bilirubin level (mg/dl)a | 0.8 (0.2–1.0) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.735 |

| Pre-operative cholangitis present | 2 | 8 | 0.710 |

| Biliary access (PTBD/endoscopy/none) | 2/9/2 | 11/23/2 | 0.368 |

| ICG-R15a | 10.6 (2.9–20.0) | 11.2 (4.2–18.4) | 0.745 |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy performed | 8 | 8 | 0.016 |

| Operating time (min)a | 623 (479–902) | 653 (444–979) | 0.564 |

| Blood loss (ml)a | 1610 (860–3840) | 1902 (861–6010) | 0.105 |

| Post-operative liver failure | 2 | 3 | 0.598 |

| Post-operative hospital stay (days) | 32 (18–88) | 35.5 (17–146) | 0.973 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1 | 1 | 0.464 |

| Tumour recurrence | 6 | 12 | 0.508 |

Values are medians (ranges).

ICG-R15, indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min; NR, patients without a portal vein resection; PVR, patients who underwent a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique.

Table 2.

Morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing a hepatectomy with and without a portal vein resection

| NR (n = 13) | PVR (n = 36) | Total (n = 49) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients with morbidity | 10 | 21 | 31 |

| Frequency of events | |||

| Wound infection | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Liver failure | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Bile leakage | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Pancreatojejunostomy insufficiency | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Outflow disturbance of hepatic vein | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| No. of patients with in hospital mortality | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| No. of patients with 90-day mortality | 2 | 0 | 2 |

NR, patients without a portal vein resection; PVR, patients who underwent a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique.

One patient in PVR group died as a result of abdominal bleeding owing to the rupture of a pseudoaneurysm of the proper hepatic artery and one patient in NR group died of liver failure during hospital stay. Two patients in the NR group died after discharge from the hospital within 90 days of surgery. One of these two patients died of carcinomatous lymphangiomatosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma and another died of other disease (detail unknown).

Histological findings and post-operative survival

Histological data are shown in Table 3. All the patients in the NR group had a negative radial margin at the hilar bile duct. The tumour recurrence rate were similar between the two groups (P = 0.508).

Table 3.

Comparison of histological findings of the patients in NR and PVR group

| NR (n = 13) | PVR (n = 36) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour extention (pT1/2a/2b/3/4)a | 0/12/1/0/0 | 4/18/1/3/10 | 0.049 |

| Nodal status (N0/N1)a | 8/5 | 24/12 | 0.667 |

| UICC Stage (I/II/IIIA/IIIB/IVA)a | 0/8/2/3/0 | 4/12/4/6/10 | 0.122 |

| Residual tumour status (R0/R1)a | 12/1 | 28/8 | 0.412 |

| Microscopic portal vein invasion (−/+) | 13/0 | 25/11 | 0.047 |

| Microscopic perineural infiltration (−/+) | 3/10 | 5/31 | 0.663 |

TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors (UICC, 7th edn).

NR, patients without a portal vein resection; PVR, patients who underwent a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique.

Six out of 13 patients in the NR group and 12 out of 36 patients in the PVR group developed tumour recurrence.

Six patients in the NR group developed tumour recurrence at a distant site (liver metastasis, lung metastasis, mediastinal lymph node metastasis and carcinomatous lymphangiomatosis) as compared with seven patients in the PVR group (liver metastasis and lung metastasis) (P = 0.128). None of patients in the NR group developed locoregional recurrence or peritoneal dissemination in comparison with five patients in the PVR group (P = 0.128).

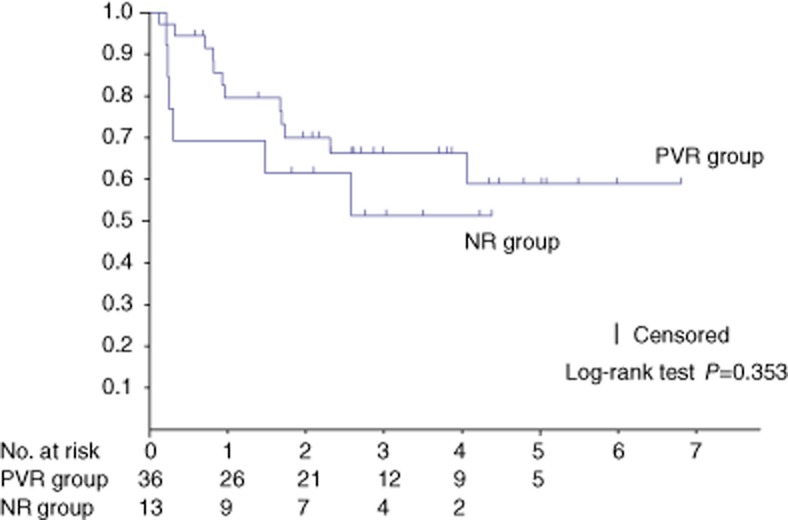

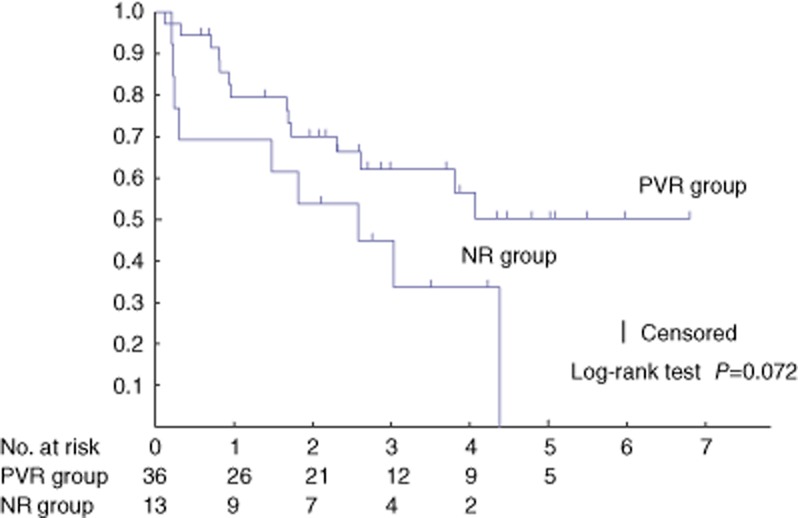

There was no significant difference in long-term survival between the two groups (P = 0.353) (Fig. 1). The recurrence-free survival also did not differ between the two groups (P = 0.072) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were respectively 80%, 66% and 59% (median survival, 20.5 months) in the patients who underwent a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique (PVR) group and 69%, 51%, and 51% (median survival, 20.5 months) in the patients without a portal vein resection (NR) group

Figure 2.

The 1- and 3-year recurrence free survival rates were, respectively, 80% and 62% (median survival, 20.5 months) in the patients who underwent a portal vein resection using the no-touch technique (PVR) group and 69% and 45% (median survival, 20.5 months) in the patients without a portal vein resection (NR) group

Discussion

Portal vein invasion is still a major obstacle to resection of advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma. However, a recent development in surgical techniques has increased the rate of resectability of hilar cholangiocarcinoma.2 Although the curative resection rate has increased owing to en bloc resection of the portal vein, overall survival remains worse in patients who have undergone portal vein resection than in those who have not.3,9–11 Moreover, even in patients with negative histological margins, local or peritoneal recurrence can occur during the follow-up period as shown in this study.

Kobayashi et al.12 reported that after a curative resection, recurrences occurred at locoregional or peritoneal sites in 19 of 42 patients. In concurrence with those findings, Jarnagin et al.4 indicated that 65% of all recurrences, including a locoregional recurrence, along the resection margin probably arose from microscopic residual disease. Most hilar malignancies have microscopic perineural tumour infiltration.3,9,12,13 In fact, in the current series, 41 patients had histological perineural invasion. Thus, recurrence is possibly related to the microscopic dissemination of cancer cells during dissection of the portal vein from the tumour when the involved bile duct lies very close to the portal vein. To avoid microscopic dissemination of cancer cells, the decision to perform a portal vein resection should be made based on pre-operative image findings and the portal bifurcation is resected without an attempt to dissect it from the hilar bile duct. The prognosis and recurrence-free survival of the patients in the PVR group was not significantly different from the prognosis and recurrence-free survival of those in the NR group (Figs 1, 2). Some authors recently reported the oncological superiority or non-inferiority of a portal vein resection with a hepatectomy to a conventional major hepatectomy.5,13 Neuhaus et al.13 reported that the prognosis of patients who underwent a hilar en bloc resection using the no-touch technique was significantly superior to the prognosis of patients who underwent a major hepatectomy alone. However, in their series, the frequency of microscopic vascular invasion was similar between both (with and without portal vein resection) groups and the decision to perform a portal vein resection was made intra-operatively. Therefore, it is possible for patients who require a portal vein resection to undergo a hepatectomy alone but with a potentially relatively poor prognosis. Meanwhile, owing to the preoperative decision to perform portal vein resection, none of the patients in the NR group had microscopic portal vein invasion and all the patients in the NR group had a negative radial margin at the hilar bile duct.

Although, in the present series, microscopic portal invasion was significantly more frequent and the T stage was significantly more advanced in the patients in the PVR group than in those in the NR group, the residual tumour status and tumour recurrence rate were similar between the groups.

Locoregional recurrence or peritoneal dissemination had occurred in five patients in the PVR group. By contrast, none in the NR group had developed locoregional recurrence or peritoneal dissemination. Locoregional recurrence or peritoneal dissemination might have been unlikely to occur because the tumour was located distant from the portal vein in all patients in the NR group. It seems to be difficult to completely prevent recurrence of locally advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma even if a R0 resection is performed using the no-touch technique. One of the reasons for this may be peritoneal recurrence associated with PTBD. Actually one patient who developed peritoneal recurrence underwent PTBD before surgery; however, there was no difference in pre-operative biliary drainage between the NR group and the PVR group (P = 0.368). Locoregional recurrence or peritoneal dissemination were less frequent compared with other reports12 and therefore this procedure may reduce the chance of locoregional recurrence or peritoneal dissemination.

Therefore, pre-operative determination to perform concomitant portal vein resection and en bloc hilar resection using the no-touch technique can provide a good chance for prolonged survival of patients with advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma, especially locally advanced disease.

The reported morbidity and mortality in patients who underwent a hepatectomy with portal vein resection were 30.0–54.0%5,9,11 and 2.0–12.4%, respectively.5,9,11,13,14 In the present study, the morbidity rate was relatively high, but there were no complications directly related to portal vein resection and reconstruction. The current mortality rate was within previous reported limits. In addition, the risk of post-operative liver failure and in-hospital mortality were not significantly different between the PVR and NR groups. Therefore, possible survival benefits of the no-touch resection of the portal vein appear to compensate for an increased risk associated with surgery, particularly when the lack of alternative curative approaches is considered.

A limitation of this study is the small number of patients in the population and a further prospective randomized study should be performed.

In conclusion, in spite of the relatively high morbidity, aggressive resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, when performed in accordance with strict management strategy, achieved acceptably low mortality. The no-touch resection of the portal bifurcation in a right hepatectomy for locally advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma enables equivalent surgical outcomes to be obtained as seen in those patients without portal vein invasion. This procedure for locally advanced disease has a positive impact on survival and is feasible in terms of long-term outcomes.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, et al. No-touch resection of hilar malignancies with right hepatectomy and routine portal reconstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:502–507. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishio H, Nagino M, Nimura Y. Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Nagoya experience. HPB. 2005;7:259–262. doi: 10.1080/13651820500373010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Nagasaka T, Nimura Y. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:720–727. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094437.68038.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarnagin WR, Ruo L, Little SA, Klimstra D, D'Angelica M, DeMatteo RP, et al. Patterns of initial disease recurrence after resection of gallbladder carcinoma and hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Implications for adjuvant therapeutic strategies. Cancer. 2003;98:1689–1700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muñoz L, Roayaie S, Maman D, Fishbein T, Sheiner P, Emre S, et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma involving the portal vein bifurcation: long-term results after resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:237–241. doi: 10.1007/s005340200025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo S, Hirano S, Ambo Y, Tanaka E, Okushiba S, Morikawa T, et al. Forty consecutive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with no postoperative mortality and no positive ductal margins. Results of a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129491.43855.6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, et al. Outcome of surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a special reference to postoperative morbidity and mortality. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. 7th edn. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyazaki M, Kato A, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Ohtsuka M, et al. Combined vascular resection in operative resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: does it work or not? Surgery. 2007;141:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song GW, Lee SG, Hwang S, Kim KH, Cho YP, Ahn CS, et al. Does portal vein resection with hepatectomy improve survival in locally advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma? Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagino M, Nimura Y, Nishio H, Ebata T, Igami T, Matsushita M, et al. Hepatectomy with simultaneous resection of the portal vein and hepatic artery for advanced perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. An audit of 50 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2010;252:115–123. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e463a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi A, Miwa S, Nakata T, Miyagawa S. Disease recurrence patterns after R0 resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97:56–64. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuhaus P, Thelen A, Jonas S, Puhl G, Denecke T, Veltzke-Schlieker W, et al. Oncological superiority of Hilar En Bloc resection for the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1602–1608. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemming AW, Mekeel K, Khanna A, Baquerizo A, Kim RD. Portal vein resection in management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]