Abstract

Background:

Childhood cancer is a stressful experience and may cause a change in the child's perception of himself/ herself, the family and the world around him/ her.

Aims:

This study sought to (a) explore the self-perception of children; and (b) examine the relation of children with others.

Materials and Methods:

The total population of the study consisted of all the children, undergoing cancer treatment at Children Cancer Hospital, located in Karachi. The participants were asked to draw a drawing on self and others. Through qualitative approach (phenomenology), themes and sub-themes were derived.

Results:

Using purposive sampling, the total sample size drawn for this study was 78 children aged 7-12, receiving treatment for cancer (1st stage) at the Children Cancer Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. The drawings of the children were categorized into facial expressions, self images and family ties. Within each category, there were sub-categories. Under facial expressions, the common emotions reflected were sadness, seriousness, anger; and pain. The self-image pictures uniformly reflected low self-esteem, especially focusing on hair loss, missing body parts. Under the category of family ties, most of the children's drawings reflected their isolation or emotional detachment from or abandonment by their family members.

Conclusions:

The study concludes that the self- image of most of the participants is deteriorated and they are socially isolated. Social and moral support can bring positive emotional development and helps to correct their self-perception.

Keywords: Battling, cancer, children, drawing, families, perception, world around them

Introduction

Childhood cancer is a stressful experience. These children undergo several medical procedures which eventually affect their behavior patterns. According to the Cancer Research UK (2011), leukemia is the most common type of cancer found in children, while tumors of the central nervous system and lymphomas are the other common types. The Pediatric Cancer Foundation estimates that each year, there are more than 14,000 children under the age of 20 are diagnosed with cancer and undergo combination of treatment including chemotherapy.

Having a child with cancer is usually regarded as “one of the most stressful experiences that a family can have”.[1] When a child is facing cancer, the parents as well as the children are confronted with a lifetime of uncertainty and physical pain.[2]

Children or adults with prior histories of emotional or mental health problems often face great challenges in coping with cancer particularly those who have suffered from depression, anxiety or serious mental health issues.[3]

A number of studies suggest that youth who are diagnosed with cancer face psychosocial adjustment problems including poor self esteem, anxiety, depression, and poor social skills.[4,5,6]

Children identify changes in their physical abilities, appearance, and moods as major concerns.[7] Beside physical changes, cancer also contributes to weakening of the sense of self in children,[8,9] while a child with a severe bodily disease experiences a threat to body image.[10] Chronic diseases, such as cancer, especially hinder the normal development of self image in its emotional, intellectual, and social dimension.[11,12,13,14,15]

A study[16] was conducted to assess the self concept of children and adolescents with cancer. The results revealed that the illness and its treatment affect the self-concept of children negatively and according to the results, the children with cancer evaluate their behavior, appearance, and performance at school negatively and express less satisfaction and happiness.

Cancer is frequently experienced by children as a violent internal and external attack because their daily routine is disrupted and they experience painful medical interventions.[17] Their view about their family members and about the world also changes.

These children undergo many medical procedures which eventually affect their behavior patterns. Thus, the ailment causes many changes in children's perception about themselves, their families and the world around them.

Research questions

What is the self-perception of children?

How do children relate to others, particularly their family members?

Study design

The study population consisted of all the children, undergoing the treatment of cancer at Children Cancer Hospital, located in Karachi. Using purposive sampling, the total sample size drawn for this study was 78 children aged 7-12, receiving treatment for cancer (1st stage) at the Children Cancer Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. The wide age range children were selected to gain the diversified view points of the children facing similar therapy and battling similar conditions.

Materials and Methods

This exploratory study used the qualitative research method, i.e., phenomenology to gain insight of the data through drawing. Drawing is considered as the universal language of childhood,[18] which can serve as a valuable tool that enables children to express their experiences. For quite some time, psychologists, educators, and artists have been intrigued by children's drawings[19] as a means to explore their imaginative world. To find out the views of children, lengthy questionnaires cannot capture the true nature of their experience and may cause discomfort at times.[20] Drawing reveals more true emotions than a solely verbal interview.[21] Children, particularly young ones are more natural and expressive through actions such as drawing.[22]

Children's human figure drawings and, in particular, family drawings are also used by psychologists to assess personality.[23,24] In short, children's drawings reveal their inner world as reflected in their representation of experiences with their own family. Therefore, the researchers selected this approach (a) due to its non-threatening orientation, (b) and due to its capacity to yield natural, spontaneous data.

The yielded 100 drawings were later on subjected to phenomenology. In this process, several drawings were discarded as they were completely vague and obscure. After this scrutiny, 78 drawings were finally selected by the researchers. From this essence categories and sub-categories were then derived. Using axial coding, the researchers have tried to establish relationships.

Ethical considerations

The purpose of the research study was discussed with the doctors and nursing staff and after this exercise only those students were selected who could willingly participate in the process. The purpose of the research was discussed with the parents who signed the informed consent. To maintain confidentiality, pseudonyms were employed.

Limitations

The study was limited to one of the major cities of Pakistan; therefore, the study may be generalized to Pakistani context on the basis of similar cultural context, but may not be generalized globally.

Results

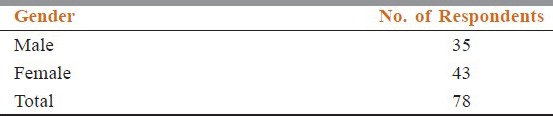

In order to elicit expressions representative of their experience with cancer, each child was handed a sheet of paper and asked to make drawing on ‘my self’ and ‘my family’. [Table 1].

Table 1.

Division of respondents on the basis of selected drawings (age level 7-12 years)

The themes and sub themes inferred from the drawings were as follows [Table 2].

Table 2.

The categories and sub-categories derived from the drawing

Discussion

Children who were diagnosed with cancer, made beautiful drawings; each reflected hidden messages. The researchers tried to look closely and derived three important categories. These included: Expressions shown on human faces, self images, and family ties. These are as under.

Facial expressions

Most of the drawings showed similar facial expressions and postures, i.e they mainly reflected grim serious faces.

Many of the younger children drew children with shabby but happy faces. Their drawings showed that they were oblivious to their pain and misery. They were living with pain, but their eyes were full of hope. This is typical of young age, as at concrete operational stage children do not know abstract reasoning.

A few younger children drew a sad face with closed eyes.

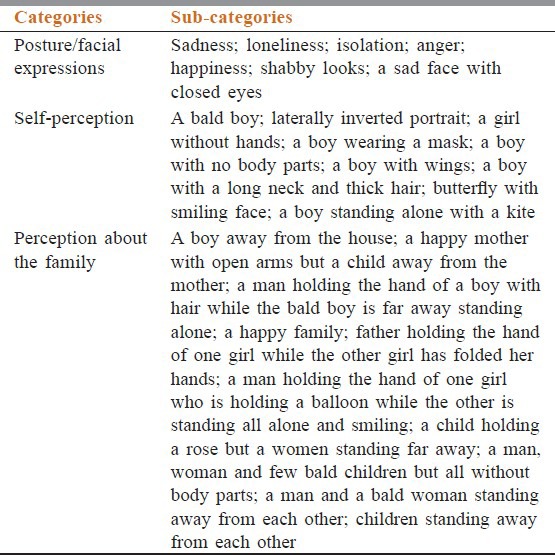

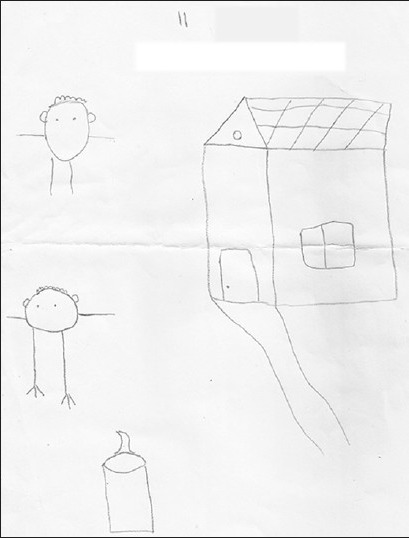

Older children drew well defined facial expressions. The common emotions shown on the faces were: sadness, [Figure 1], seriousness, anger; and pain. They depicted themselves in the hospital and in isolated places. Children over the age of eleven develop abstract reasoning and can foresee and predict events and behavior. The expressions on the faces they drew reflected inner fear, uncertainty, and disbelief.

Figure 1.

The self-image of psychologically disturbed person

The gender difference was also obvious: girls used lighter, softer strokes with dim expressions. They were not very clear in showing expressions. The younger girls used fantasy and imagination, showing themselves and other siblings with fairies and dolls. As compared to their female counterparts, the boys made practical darker strokes. They clearly showed the facial expressions.

Most of the children showed themselves in the standing posture.

Their self-perception

Children's self portrayal clearly showed weak self-images. They were candid and brutal in drawing themselves. Their descriptions included: a bald boy; laterally inverted portrait; a girl without hands; a boy wearing a mask; a boy with no body parts; a boy with wings; a boy with a long neck and thick hair; butterfly with smiling face; a boy standing alone with a kite. All these portrayals showed and described different and unique ways of perceiving self. Their drawings reflected the fact that they do not consider themselves complete and normal. It is heartening that children with cancer can feel and hope like normal children, while physically being different. Perhaps these children lived in the two worlds of hope and despair, war and peace, and pain and joy.

It was quite clear that trapped in their sick bodies, they saw themselves isolated and cut off from the rest of the world.

In most of the drawings, children portrayed themselves as a bald boy/girl. Since these children were going through the phase of chemotherapy, they lost their hair; therefore, they perceived themselves as being different. Many children consider hair loss as the most upsetting part of chemotherapy. It is an obvious sign to themselves and their peers that they are seriously ill. It makes them look different and as young children who are desperate to fit in with their peer group, they find this difficult to adjust to.[25]

Hair loss is a transient but often psychologically devastating consequence of cancer chemotherapy. For some patients, the emotional trauma may be so severe as to lead to discontinuing or refusing treatment that might otherwise be beneficial.[26,27,28,29] Many people, particularly children view it as emotional trauma. Those drawings, which portrayed boy/girl without hair were often combined with another picture of a child with hair. This was natural as the children with cancer perceive themselves different from others. Their image about self is often distorted due to baldness.

There was an interesting contrast to note that most of the children undergoing treatment for cancer drew their family members with full hair and often looking happy and smiling, while their self image was drawn with either covered head, bald head or less hair. Only few of the children drew long and thick hair on their self portrait.

The possible stigma associated with children with cancer highlights the risk of a self-fulfilling prophecy placing them at risk for social isolation and alienation even after treatment has ended.[30] In few of the drawings, children made a face with eyes but no other parts of the face were visible. The researcher observed that since most of the children wear a mask on their faces in the hospital, they perceive themselves the same. Such drawings reflect isolation and deteriorated self-image.

Most of the cancer patients wear a mask to protect themselves from germs while they are immunosuppressed but children do not like masks as they believe that these masks are to hide the changes in their faces from others.[31]

Children facing cancer develop many other problems. The problems often reported include anxiety, fear, depression, extreme dependency on parents, sleep disturbance, regression, anger, and withdrawal.[32,33] Children's drawings are believed to reveal the child's inner mind. The clues are believed to lie in the child's alterations of line quality, disguising shapes, and using unusual signs or symbols.[34] Anxiety is represented through intensity of line pressure, excessive shading, smallness of the figure, and rigidity of the drawing process. Two of the children drew heavily scratched lines and did excessive shading, while four children drew magnified images. Many faces were drawn with sad emotions, which also reflect anger and sadness.

When children have low self-esteem, it is difficult for them to adjust and accept the changes in their looks. The low self-image is derived from the side effects of chemotherapy, which alter physical appearance, such as hair loss, weight fluctuations, or loss of limb through amputation. These emotional difficulties are aggravated by a fear of being rejected and teased by peers.[35]

During the childhood years, physical appearance and social acceptance are important predictors of adjustment. Varni et al., (1995)[36] concluded that higher perceived physical appearance predicted lower depressive and anxious symptoms and higher general self-esteem.

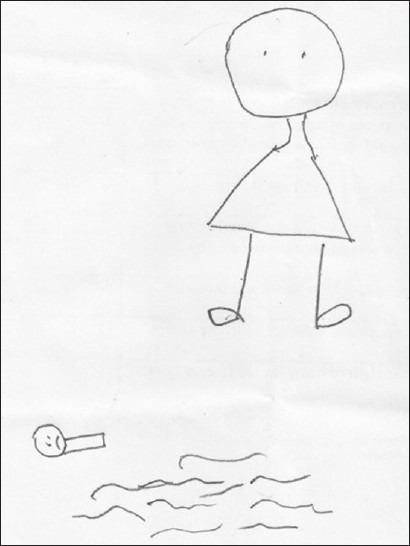

There were more than eight drawings, where children below the age of 6 drew a boy/girl with missing body parts [Figure 2]. Several theories have been proposed to explain the reasons why young children tend to draw unrealistic or incomplete human forms. Some experts suggest that children omit bodily features because of a lack of knowledge about the different parts of the human body and how they are organized. Others argue that children don’t look at what they are drawing; instead, they look at the abstract shapes already in their repertoire and discover that these forms can be combined in various ways to symbolize objects in the world. Still others believe that children are simply being selective and drawing only those parts necessary to make their figures recognizable as human forms. There is considerable evidence to suggest that children who draw figures without bodies, arms or legs are certainly capable of identifying these parts when asked to do so, but the idea of creating a realistic likeness of a person has not yet occurred to them or occupied their interest.[37]

Figure 2.

The portrayal of emotional and psychological disturbance

Researchers believe that social support enhances personal functioning and assists in coping adequately with stressors.[38,39,40] Few of the children also drew positive self images. One of the children drew a beautiful drawing of a boy with a long neck and thick hair. Similarly, a girl drew a butterfly with a smiling face and a boy drew a picture of a boy with wings. There were two pictures in which children made happy faces and healthy bodies too. Social support always brings positive emotional development in these children.

Previous research[41] has shown that emotional reactions of 123 hospitalized children and their mothers were evaluated during standard isolation. Self-report surveys and behavioral observations by nurses indicated that patients and parents in both isolation facilities had overall high levels of hospital-related anxiety and depression which varied with the patient's chronological age.

Children battling with cancer are isolated in a hospital during treatment. Since they find themselves in isolation, it sometimes increases their level of loneliness. One of the children drew a sad boy standing alone with a kite in a garden, which somehow reflects the portrayal of isolation.

Anxiety is a behavior that is commonly seen in all children with cancer when they are diagnosed with cancer and become aware of the seriousness of the disease.[42] Most of the children drew either emotionless or sad faces in the drawings, which may be due to anxiety.

Perceptions about the family

Interpersonal relationships are vital to the individual's psychological and physical well being in that they relate positively to life satisfaction and enjoyment.[43]

Children, particularly those who are diagnosed with cancer need to have a close relationship with their family members. Young children may become insecure and want to be close to adults all the time, or behave badly to get attention. Older children may think that they are being asked to do too much-or feel torn between staying home and spending time with friends.[44]

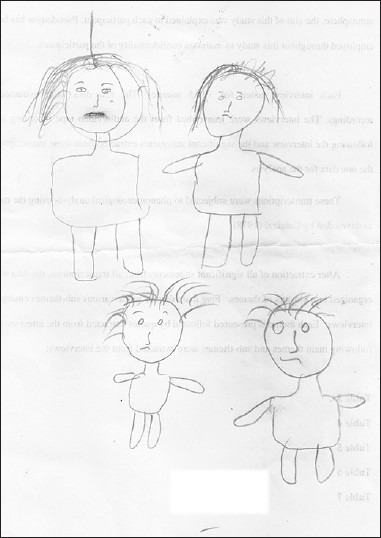

Most of the children at the hospital were found with their mothers while there were only few cases, where either father or both the parents accompanied the child. There were few drawings where children drew single parent accompanying them, while few of the drawings showcased the portrayal of detachment from both their parents; however, only three children drew complete family on the paper.

Certain functional areas may be affected by chronic illness, including social-emotional functioning and family functioning.[45] One of the children drew a boy away from the house [Figure 3] while in four of the drawings children drew a man/woman, holding the hand of a boy/girl with full hair, while the bald child was standing all alone [Figure 4]. Children fighting cancer are often inactive in social and family gathering and face a variety of stressful circumstances that require coping responses, indicating a need for preventive work.[46]

Figure 3.

Self-image of a person and the surrounding

Figure 4.

Portrait of emotional detachment from family

Two main areas of functioning for children with cancer that often are affected are social adjustment with peers and emotional well-beings.[47] Many children view their parent as their role model to cure their cancer.

Children who believe their parents have the power to cure their cancer but choose to let them suffer through chemotherapy instead will feel rejected. Such children are likely to withdraw into themselves believing that if their own parents are helpless then no other adults have a chance of being effective.[48]

One of the children drew a portrayal of a child holding a rose but a woman standing far away from him. The picture clearly indicated that the child wanted to give the rose to someone but that person was far away from him.

One of the children drew a man, woman, and few bald children but all without body parts which may indicate that the siblings may also be facing the similar ailment.

Children with cancer, especially those who have a higher level of behavioral problems, are more likely to view themselves as having lower levels of social acceptance from peers.[49] There was a drawing in which a child drew a boat where two people were sailing, while another child was standing all alone in an isolated corner.

A study conducted by Noll et al,[50] evaluated the psychosocial adaptations of children with cancer.. Although the peer report data showed that children with cancer had a social reputation as significantly more socially isolated, no significant differences were found for their popularity, number of mutual friends, loneliness, or self-worth. Findings suggest that children with cancer have a reputation as more socially isolated.

Conclusion

Our study concludes that most of the children under the treatment of cancer at the Children Cancer Hospital view themselves in isolation and their self image is often poor due to baldness and wearing mask; only few children drew positive self images (particularly those between the age of 11 and 12). In most of the cases, their self perception is quite little (particularly of those between the age group of 9 and 12). They often have low self-esteem. Few children drew sad faces which expressed their anger, anxiety and emotional disturbance. Few of the drawings showcased the portrayal of detachment from parents. Most of these children were socially isolated. Their perception of the love of their parents and friends for other children was very visible in the drawing (particularly of those between the age of 10 and 12), where, at many instances, a child was drawn away from the others. Children battling with cancer need the love of their parents and siblings in order to help them cope with anxiety. Social and moral support can bring positive emotional development and can help develop positive self-perception. We recommend that the entire community participates in helping children who are fighting against deadly ailments. As an inclusive society, people should foster love and care for those in need. Societies that invest in children are bound to receive the same care and respect from the future generations.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kazak AE, Nachman GS. Family research on childhood chronic illness: Pediatric oncology as an example. J Fam Psychol. 1991;4:462–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eiser C. Comprehensive care of the child with cancer: Obstacles to the provision of psychological support in pediatric oncology: A comment. Psychol Health Med. 1996;1:145–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaupré R. Psychological aspects of coping with cancer. [Last accessed on 2012 Mar 5]. Available from: http://cpancf.com/art i cles_ f iles/PsychologicalCopingCancer.asp .

- 4.Deasy-Spinetta P. The school and the child with cancer. In: Spinetta JJ, Deasy-Spinetta P, editors. Living with Childhood Cancer. Toronto: C. V. Mosby; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Futterman EH, Hoffman I. Transient school phobia in a leukemic child. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1970;9:477–94. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61854-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg HS, Kazak AE, Meadows AT. Psychological adjustment in 8- to 16-year-old cancer survivors and their parents. J Pediatr. 1989;114:488–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman K, O’Dell C, Meola C. Childhood brain tumors: Children's and siblings’ concerns regarding the diagnosis and phase of illness. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2003;20:133–40. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2003.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritchie M. Psychosocial functioning of adolescents with cancer: A developmental perspective. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1992;19:1497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodgate RL. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba; 2001. Symptom experiences in the illness trajectory of children with cancer and their families. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodgate RL. Adolescents perspective of chronic illness. J Pediatric Nurs. 1998;13:210–23. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(98)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White NE, Richter JM, Fry C. Coping, social support and adaptation to chronic illness. West J Nurs Res. 1992;14:211–24. doi: 10.1177/019394599201400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cincotta N. Psychosocial issues in the world of children with cancer. Cancer. 1993;71(10 Suppl):3251–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10+<3251::aid-cncr2820711718>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enskar K, Carlsson M, Golstater M, Hamrin E. Symptom distress and life situation in adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:23–33. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199702000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eapen V, Revesz T, Mpofu C, Daradkeh T. Self-perception profile in children with cancer: Self vs parent report. Psychol Rep. 1999;84:427–32. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pendley JS, Dahlquist LM, Dreyer Z. Body image and psychosocial adjustment in adolescent cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:29–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyritsi H, Matziou V, Papadatou D, Evagellou E, Koutelekos G, Polikandrioti M. Self concept of children and adolescents with cancer. Health Sci J. 2007;3:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeltzer L. Cancer in adolescents and young adults psychosocial aspects. Long-term survivors. Cancer. 1993;71(10 Suppl):3463–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10+<3463::aid-cncr2820711753>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin J. 2nd ed. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1984. Child art therapy: Understanding and helping children grow through art. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golomb C. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1992. The child's creation of a pictorial world. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phipps S, Fairclough D, Mulhern RK. Avoidant coping in children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20:217–32. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross J, Hayne H. Drawing facilitates children's verbal reports of emotionally laden events. J Exp Psychol. 1998;4:163–79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malchiodi C. Understanding somatic and spiritual aspects of children's art expressions. In: Malchiodi C, editor. Medical Art Therapy with Children. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knoff HM, Prout HT. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1985. Kinetic drawing system for family and school: A handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naglieri JA. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1988. Draw-a-Person: A quantitative scoring system. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallon B. United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd; 1998. Helping children to manage loss. Positive strategies for renewal and growth. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorr VJ. A practitioner's guide to cancer-related alopecia. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:562–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussein AM. Chemotherapy-induced alopecia: New developments. South Med J. 1993;86:489–96. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruning N. Hair, skin, and nail effects. In: Bruning N, editor. Coping With Chemotherapy: How to Take Care of Yourself While Chemotherapy Takes Care of the Cancer. New York: Dial Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cline BW. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced alopecia: A review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 1984;7:221–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vannatta K, Gartstein MA, Short A, Noll RB. A controlled study of peer relationships of children surviving brain tumors: Teacher, peer, and self ratings. J Pediatr Psychol. 1998;23:279–87. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.5.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Why do children with cancer where a kind of mask over their face? [Last accessed on 2012 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.mcrh.org/Cancer-Child/16654.htm .

- 32.Apter A, Farbstein I, Yaniv I. Psychiatric aspects of pediatric cancer. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2003;12:473–92. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(03)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Dongen-Melman JE, Sanders-Woudstra JA. Psychosocial aspects of childhood cancer: A review of the literature. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1986;27:145–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greig A, Taylor J. London: SAGE Publications; 1999. Doing research with children. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross DM, Ross SA. Childhood pain: The school-aged child's viewpoint. Pain. 1984;20:179–91. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90099-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varni JW, Katz ER, Colegrove R, Jr, Dolgin M. Perceived physical appearance and adjustment of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A path analytic model. J Behav Med. 1995;18:261–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01857873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winner E. Cambridge, Mass and London. England: Harvard University Press; 1982. Invented Worlds: The psychology of the arts. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubow EF, Tisak J, Causey D, Hryshko A, Reid G. A two-year longitudinal study of stressful life events, social support, and social problem solving skills: Contributions to children's behavioral and academic adjustment. Child Dev. 1991;62:583–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malecki CK, Demaray MK. Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale. Psychol Sch. 2002;39:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weigel DJ, Devereux P, Leigh GK, Ballard-Reisch D. A longitudinal study of adolescents’ perceptions of support and stress: Stability and change. J Adolesc Res. 1998;13:158–77. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powazek M, Goff JR, Schyving J, Paulson MA. Emotional reactions of children to isolation in a cancer hospital. J Pediatr. 1978;92:834–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kyngas H, Mikkonen R, Nousiainen EM, Rytilahti M, Seppanen P, Vaattovaara R, et al. Coping with the onset of cancer: Coping strategies and resources of young people with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10:6–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Karney BR. Optimizing longitudinal research for understanding and preventing marital dysfunction. In: Bradbury TN, editor. The Developmental Course of Marital Dysfunction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emotions and Cancer. [Last accessed on 2012 Mar 3]. Available from: http://www.cancersa.org.au/aspx/emotions_cancer.aspx .

- 45.Garrison W, McQuiston S. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1989. Chronic illness during childhood and adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kazak AE, Rourke MT, Alderfer MA, Pai A, Reilly AF, Meadows AT. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: A blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1099–110. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA. Pediatric oncology: Psychosocial outcomes for children and families. In: Roberts MC, editor. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. 4th ed. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 342–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Connor KJ, Ammen S. London: Academic Press; 1997. Play Therapy Treatment Planning and Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloper T, Larcombe IJ, Charlton A. Psychosocial adjustment of five-year survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Educ. 1994;9:163–9. doi: 10.1080/08858199409528300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noll RB, LeRoy S, Bukowski WM, Rogosch FA, Kulkarni R. Peer relationships and adjustment in children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:307–26. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]