Abstract

Bartonella species have been shown to cause acute, undifferentiated fever in Thailand. A study to identify causes of endocarditis that were blood culture-negative using routine methods led to the first reported case in Thailand of Bartonella endocarditis A 57 year-old male with underlying rheumatic heart disease presented with severe congestive heart failure and suspected infective endocarditis. The patient underwent aortic and mitral valve replacement. Routine hospital blood cultures were negative but B. henselae was identified by serology, PCR, immunohistochemistry and specific culture techniques.

Key words: bartonella, endocarditis, cat scratch disease, Thailand.

Introduction

Blood culture-negative endocarditis (BCNE) is a term used in the cardiology literature to describe cases of infective endocarditis for which there is no bacterial growth in three independent blood samples cultured on standard aerobic media after seven days of incubation and subculturing.1 However, with specialized culture techniques, PCR, and serology, fastidious, slow growing bacteria can sometimes be identified in such cases. BCNE accounts for 2.5–31% of all cases of endocarditis in industrialized countries and for up to 76% of cases in the developing world.2 Routine blood culture fails to identify a causative organism in 40% of infectious endocarditis cases at Khon Kaen University Hospital, a tertiary care facility in northeast Thailand,3 and the case fatality rate of BCNE in Khon Kaen is 38%.3 A collaborative project aimed at elucidating the causes of BCNE in Khon Kaen was begun in 2010 with objectives to improve clinical outcomes and identify potential preventive interventions. We describe the first known case of Bartonella spp. endocarditis in Thailand.

Case Report

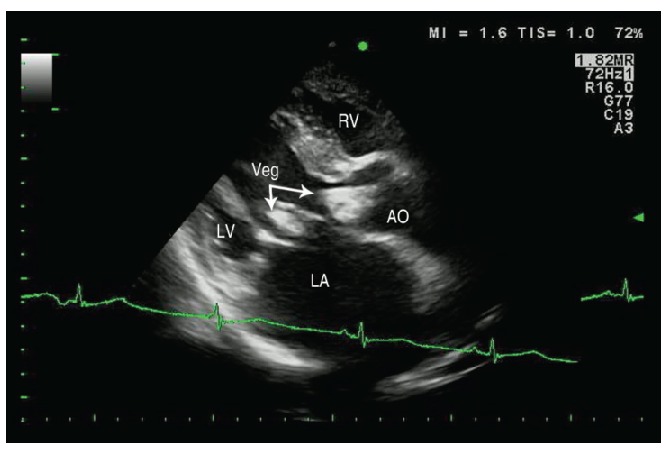

A 57-year old male poultry farmer with underlying rheumatic heart disease presented to a local hospital with a 5 day history of fever, muscle pain and shortness of breath. He was found to be in congestive heart failure and was transferred to the regional cardiac referral center, Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen, Thailand. On admission, he had fever of 39.0°C., heart murmurs consistent with aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, mitral stenosis and mitral regurgitation, signs of congestive heart failure, anemia and digital clubbing. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a large, mobile vegetation on the aortic valve (Figure 1) and on the mitral valve.

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography showing two large vegetations (Veg), one at the aortic valve (right arrow) and one at the mitral valve (bottom arrow).

Intravenous ampicillin and gentamycin were begun on admission and blood transfusions and dopamine circulatory support was given. However, symptoms of congestive heart failure worsened and 8 days after admission the patient underwent aortic and mitral valve replacement. Histopathological examination of the heart valve tissue showed chronic, active, suppurative endocarditis with hemosiderosis.

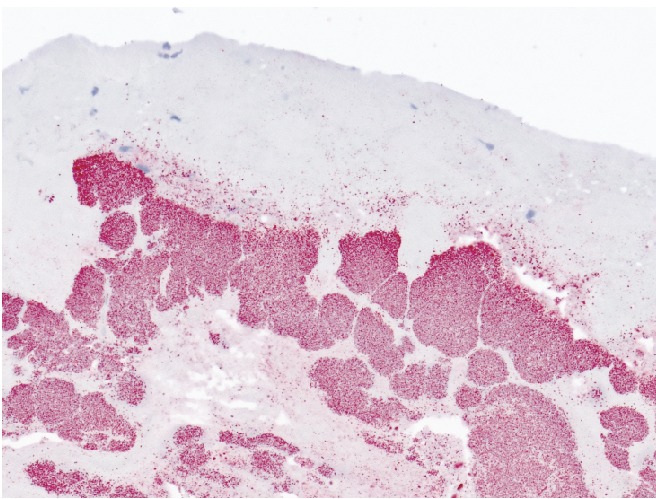

Three sets of routine aerobic blood cultures were negative. Serological testing was performed using an indirect immunofluourescent antibody assay using antigens prepared from four Bartonella species. Serology was diagnostic for B. henselae, with a serum antibody titer of 1:512 at enrollment and a titer of 1:256 twenty-eight days later. B. henselae was also demonstrated in heart valve tissue by shell vial culture, by real-time PCR, and by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 2).4

Figure 2.

Immunoalkaline phosphatase staining of resected heart valve tissue using a monoclonal antibody reactive only with Bartonella henselae shows bacteria staining red (20× magnification).

The patient was started on therapy for Bartonella endocarditis with ampicillin and gentamycin. Two months after surgery his cardiac disease stabilized and he was discharged from hospital. However, approximately one month after discharge, the patient died suddenly at home, apparently from complications of anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion

Bartonella are fastidious, gram-negative pathogenic bacteria associated with diverse mammalian species. Previous collaborative research conducted by the US CDC's International Emerging Infections Program and Division of Vector Borne Diseases confirmed Bartonella infections among patients with acute undifferentiated fever in Thailand and identified a new species of Bartonella.5–7 Bartonella causes a wide spectrum of clinical infections, ranging in severity from asymptomatic or mild febrile illness to endocarditis. There is growing evidence from Europe,8 the USA9 and from developing countries10 that Bartonella are an important cause of human endocarditis. We describe the first reported case of Bartonella spp. endocarditis in Thailand. Our patient was infected with B. henselae, the etiologic agent of cat scratch disease. Ownership of cats and underlying heart valve damage are predisposing factors for B. henselae endocarditis.11 The patient had prior significant aortic and mitral valve defects. Our patient had no cats at home, but his neighbor had a cat from which B. henselae was isolated. However, given the high prevalence of Bartonella infections in cats, we cannot confirm a link to this case. The clinical and public health implications of this finding are important due to the historically high rates of rheumatic heart disease in Thailand, which can often be complicated by infective endocarditis. Increased awareness of this pathogen as a potential agent for infective endocarditis can sensitize physicians to considering Bartonella in the differential diagnosis, to develop diagnostic capacity in Thailand, and help to assure appropriate therapy, which differs from standard therapy for infective endocarditis. Regional surveillance efforts to examine domestic animals, rodents and ectoparasites for Bartonella species are also currently being conducted to help define the epidemiology, clinical spectrum, vectors, and animal reservoirs for Bartonella endocarditis in Thailand.

Acknowledgements:

we thank the following investigators for their invaluable help with this study. From Khon Kaen University: Viraphong Lulitanond, Piroon Muksikapan and Burapha Bussadhamma. From the Division of Vector Borne Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colorado: Jennifer K Iverson and M Diaz. From the National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases, CDC, Atlanta: Christopher Paddock and Patricia Greer in Atlanta. From IEIP, Nonthaburi, Thailand: Sumalee Boonmar and Somsak Thamthitiwat. From The University of the Mediterranean, Marseille, France: Pierre-Edouard Fournier and Didier Raoult.

References

- 1.Brouqui P, Raoult D. Endocarditis due to rare and fastidious bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:177–207. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.177-207.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benslimani A, Fenollar F, Lepidi H, Raoult D. Bacterial zoonoses and infective endocarditis, Algeria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:216–24. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.040668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pachirat O, Chetchostisakd P, Klungboon-krong V, et al. Infective endocarditis: prevalence, characteristics and mortality in Khon Kaen, 1990–1999. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daybell D, Paddock CD, Zaki SR, et al. Disseminated infection with Bartonella henselae as a cause of spontaneous splenic rupture. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e21–4. doi: 10.1086/422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosoy M, Bai Y, Sheff K, et al. Identification of Bartonella infections in febrile human patients from Thailand and their potential animal reservoirs. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:1140–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhengsri S, Bagget H, Peruski L, et al. Bartonella spp. infections, Thailand. Emerg Inf Dis. 2010;16:743–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1604.090699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosoy M, Morway C, Sheff KW, et al. Bartonella tamiae sp. nov., a newly recognized pathogen isolated from three human patients from Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:772–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02120-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houpikian P, Raoult D. Blood culture-negative endocarditis in a reference center. Medicine. 2005;84:162–73. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000165658.82869.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tunkel AR, Kaye D. Endocarditis with negative blood cultures. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1215–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204303261809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balakrishnan N, Menon T, Fournier P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana and Coxiella burnetti as causes of endocarditis, India. Emerg Infec Dis. 2008;14:1168–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.071374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosbacher ME, Klotz S, Klotz J, Pinnas JL. Bartonella henselae and the potential for arthropod vector-borne transmission. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:471–7. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]