Abstract

Several exanthems including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome are suspected to be caused by viruses. These viruses are potentially dangerous. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome is related to hepatitis B virus infection which is the commonest cause of hepatocellular carcinoma, and Epstein-Barr virus infection which is related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Pityriasis rosea has been suspected to be related to human herpesvirus 7 and 8 infections, with the significance of the former still largely unknown, and the latter being a known cause of Kaposi's sarcoma. Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome is significantly associated with human B19 erythrovirus infection which can lead to aplastic anemia in individuals with congenital hemoglobinopathies, and when transmitted to pregnant women, can cause spontaneous abortions and congenital anomalies. With viral DNA sequence detection technologies, false positive results are common. We can no longer apply Koch's postulates to establish cause-effect relationships. Biological properties of some viruses including lifelong latent infection, asymptomatic shedding, and endogenous reactivation render virological results on various body tissues difficult to interpret. We might not be able to confirm or refute viral causes for these rashes in the near future. Owing to the relatively small number of patients, virological and epidemiology studies, and treatment trials usually recruit few study and control subjects. This leads to low statistical powers and thus results have little clinical significance. Moreover, studies with few patients are less likely to be accepted by mainstream dermatology journals, leading to publication bias. Aggregation of data by meta-analyses on many studies each with a small number of patients can theoretically elevate the power of the results. Techniques are also in place to compensate for publication bias. However, these are not currently feasible owing to different inclusion and exclusion criteria in clinical studies and treatment trials. The diagnoses of these rashes are based on clinical assessment. Investigations only serve to exclude important differential diagnoses. A wide spectrum of clinical features is seen, and clinical features can vary across different populations. The terminologies used to define these rashes are confusing, and even more so are the atypical forms and variants. Previously reported virological and epidemiological results for these rashes are conflicting in many aspects. The cause of such incongruence is unknown, but low homogeneity during diagnosis and subject recruitment might be one of the factors leading to these incongruent results. The establishment and proper validation of diagnostic criteria will facilitate clinical diagnosis, hasten recruitment into clinical studies, and allow results of different studies to be directly compared with each another. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews would be more valid. Diagnostic criteria also streamline clinical audits and surveillance of these diseases from community perspectives. However, over-dependence on diagnostic criteria in the face of conflicting clinical features is a potential pitfall. Clinical acumen and the experience of the clinicians cannot be replaced by diagnostic criteria. Diagnostic criteria should be validated and re-validated in response to the ever-changing manifestations of these intriguing rashes. We advocate the establishment and validation of diagnostic criteria of these rashes. We also encourage the ongoing conduction of studies with a small number of patients. However, for a wider purpose, these studies should recruit homogenous patient groups with a view towards future data aggregation.

Key words: human herpesvirus, meta-analyses, paediatric dermatology, polymerase chain reaction, regression analysis, systematic reviews.

Introduction

The apparently programmed clinical courses, spontaneous remissions after 2–12 weeks, apparent immunities after the first eruptions, laboratory findings, and epidemiology findings led us to suspect that several skin eruptions, namely Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS, also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood)1–3 (Figure 1), pityriasis rosea (PR)4–6 (Figure 2 and Figure 3), asymmetrical periflexural exanthem (APE, also known as unilateral latero-thoracic exanthem)7–9 (Figure 4), unilateral mediothoracic exanthem (UME, a variant of APE),10 eruptive pseudoangiomatosis (EP),11–13 and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome (PPGSS),14–16 are related to viral infections17 (Figures 5–7).

Figure 1.

Papulovesicular lesions over the forearms, wrists, hands, legs, ankles, and feet of a Chinese child with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (papular acrodermatitis of childhood).

Figure 2.

Typical lesions of pityriasis rosea on the trunk of a woman with pityriasis rosea.

Figure 3.

Typical herald patch in pityriasis rosea, showing collarette scaling configuration.

Figure 4.

Typical unilateral latero-thoracic exanthema around right axilla in an adult Indian patient.

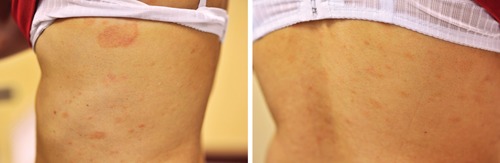

Figure 5.

Erythematous papular lesions significantly more on the right neck and shoulder than on the left aspect of neck and left shoulder of a man with asymmetric periflexural exanthema.

Figure 7.

Typical lesions of papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome in an Indian child.

Figure 6.

Typical lesions of eruptive pseudoangioma in an adult Indian patient.

Epidemiological evidence suggests that these exanthems could be much commoner than generally thought.18–29 Most patients consult primary care clinicians in the first instance 30 who may significantly under-diagnose these rashes.31

The gravity of these exanthems is largely unknown. Severe complications might not have been noticed up to now, just as it took many years after the first case of Kawasaki disease was seen for coronary pathologies to be recognised as complications of this disease.32 These exanthems can also cause significant morbidities and impacts on quality of life of patients.33–35 With the viral etiologies unknown, antiviral therapies and immuno-modulating therapies are already in use.36–38 These agents might cause significant adverse effects, and we have to gather adequate data to support or refute their use.

In this article, we shall briefly review our current understanding of these rashes, address the strengths and weaknesses of our present directions in investigations, explore whether the use of diagnostic criteria (DC) can overcome these weaknesses, and speculate on the potential pitfalls of utilizing such DC.

Virological investigations

GCS had been found to be significantly associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.39–41 More recent research, however, implicates Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)42–44 and other viruses45,46 as alternative etiologies of GCS. HBV is the most common cause of hepatocellular carcinoma,47 while EBV is significantly associated with Hodgkin's lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.48

Various viruses might cause APE, with no single virus being put under the spotlight.26,49–51 No single virus has been significantly associated with EP.52–54 PPGSS is significantly associated with human B19 erythrovirus (HB19EV, previously called parvovirus B19) infections.55–57 However, other viruses are also implicated.58–61 HB19EV infection can cause aplastic anemia,62 the risk of which significantly increased if the patient had one of the congenital hemoglobinopathies.62 If pregnant women get infected by HB19EV, the risks of spontaneous abortion and congenital anomalies rise sharply.63

Human herpesvirus (HHV)-7 infection has been suspected to be the cause of PR.64–71 However, individual investigators reported controversial results.72–75 Conflicting results were also reported for HHV-6a, 6b, and 8.73,76,77 Cytomegalovirus,75,78 EBV,75,78 HB19EV,77 Chlamydia spp.,79 Legionella spp.,79 and Mycoplasma spp.79 infections have been suspected to be related to PR. HHV-8 causes Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with HIV infection. The long-term implications of HHV-6, -7, and -8 are still unknown.

Another debate concerns how many data are adequate to prove a causal relationship. The time-honoured Koch's postulates80 seem to cater more for bacteria than for viruses. Hill's criteria for causality81 might be more applicable to environmental non-infectious causes. Newer guidelines based on DNA sequence detection techniques82 were not universally accepted. False positive results are particularly difficult to be minimized, as one viral DNA copy can theoretically lead to a positive result. The interpretation of DNA or messenger RNA transcripts sequence-based detection methods is particularly difficult for viruses with inherent pathogenetic properties of lifelong infection, latent infection, asymptomatic virus shedding, and endogenous reactivation. Apart from seroconversion signifying primary infection, IgM results are not convincing owing to cross-reactivity, while sequential IgG titers were of limited value unless investigations are conducted in parallel. Integrated approaches are now being advocated.83–85 However, all studies mentioned above adopted different inclusion criteria, also making application of integrated approaches difficult.

We know, therefore, that although these rashes are usually self-limiting, they may be associated with viruses causing long-term complications. These associations may not be resolved in the near future.

Epidemiology studies

Descriptive epidemiology

There have been many epidemiological reports for GCS,18–21,40 PR,22–25 APE26 and EP.27–29 For GCS, five epidemics have been reported, three20,21,41 being in Japan, affecting 54,41 153,21 and 1420 infants and young children, respectively. Most cases were related to HBV infection.20,21,41 In an epidemic reported in Italy, 5 infants and young children were affected,18 all found to have had recent EBV infection.18 A mini-epidemic involving 3 children was also reported in India.86

Many systematic epidemiology studies22–25,87–96 were reported for PR. A meta-analysis 97 reported that the overall incidence of PR was around 0.68 per 100 dermatological patients in specialist settings. In the community, the incidence was estimated to be 172.2 per 100,000 person-years,89 with the prevalence being 0.6% at any one time for adolescents and young adults.25 The male to female ratio is 1:1.44.97

Only one epidemiology report was available for APE,26 concerning 67 infants and children over a period of 32 months. The male to female ratio was 1:1.23. For EP, three case series52–54 were reported with 7 infants,54 9 adults,52 and 7 adults,53 the male to female ratio being 1:0.40,54 1:8.00,52 and 1:6.00,53 respectively. For PPGSS, there was a case series reporting 36 children at a median age of 23 months.61

We believe, therefore, that in the community these rashes may be more common than is usually thought. We may miss epidemics and mini-epidemics simply because many patients are not correctly diagnosed.

Analytical epidemiology

Seasonal variations and geographical differences are the most commonly used analytical approaches, with other independent variables being contact history, immunization history, previous exanthems, previous febrile illnesses, and prodromal symptoms.98 No analytical epidemiology study was reported for GCS. For PR, studies87–94,96,99,100 reported conflicting results on seasonal variation. PR was reported not to be associated with climate data including the monthly mean temperature, mean total rainfall, and mean relative humidity.100 No study was reported for APE, EP and PPGSS on these analytical variables.

Another analytic approach is temporal and spatial-temporal clustering. Clustering might substantiate diseases being contagious, and have been applied in Kawasaki disease.101 Powerful analytical tools are now available to detect clustering.102 Spatial-temporal clustering was reported for GCS86 while temporal clustering was reported for PR.100,103

We, therefore, have evidence that these rashes can be contagious. To ascertain how contagious they are and to discover the routes of spreading the microbes we need more epidemiological data from a large number of patients with high homogeneity.

Treatment trials

Treatment trials can be conducted even if the underlying pathogenesis of a disease is not completely understood 104. For GCS, no systematic treatment trial was reported, and treatment consensus was not reached from case reports.17,18,20,41,44,105–108 No randomized treatment trial was reported for APE, EP, and PPGSS.

For PR, various approaches have been adopted, including sunlight,109 ultraviolet radiation,110 non-antiinflammatory antibiotics,111 antiinflammatory antibiotics,36–39,108 antiviral agents,36 topical and systemic histamine antagonists,112 topical and systemic corticosteroids,100,113 topical soothing lotions,108,113 emollients,113 and herbal remedies.113 One pseudo-randomized controlled trial (allocating patients to treatment and control groups alternatively instead of randomly)39 and three randomized controlled trials (Saveleva and Selinski, unpublished data, 2008; and114,115).

Were retrievable in a Cochrane systematic review.113 Inclusion criteria of all these studies varied, and none of the four trials provided adequate evidence for or against the effectiveness of erythromycin (Saveleva and Selinski, unpublished data, 2008; and39), systemic corticosteroids,114 systemic antihistamine,115 and glycyrrhizin (a herbal remedy)115 in PR, partly due to the small number of patients, and partly related to imperfect methodologies.113

We, therefore, realize that many treatment modalities being used are not substantiated by evidence of their efficacy or their adverse effects. To obtain more evidence, treatment trials need to have more power.113

Number of patients, power, publication bias and meta-analyses

Most of the studies reviewed above include only a small number of patients. The results might bear low statistical power, low clinical significance, and high risks of type 1 and type 2 errors. Moreover, trials with small numbers of patients are less likely to be published in mainstream dermatology journals, leading to publication bias. If one performs a meta-analysis or systematic review with published studies only, one runs the risk of missing the seriousness of unpublished studies. This is why Cochrane Reviews welcome unpublished studies.113 One study quoted in this article, for example, is still unpublished (Saveleva and Selinski, unpublished data, 2008).

With the risk that journals may not accept articles for publication, the conduction of small-scale studies should not be discouraged, as few data are better than no data, and aggregation of data from small-scale studies would form large pools of patients and control subjects.116 With techniques to minimize publication bias,117,118 conglomerated results can be powerful.

However, from the brief review above, such aggregation of data is not yet possible, as the inclusion and exclusion criteria of various studies are different, leading to low homogeneity of the patient groups. The incongruent results for virological and epidemiological studies for PR, for example, might be partly related to the heterogeneity of the patients recruited. Imprudent use of meta-analyses would lead to invalid and incongruent conclusions, which might adversely affect patient care.

Diagnostic criteria

We, therefore, propose validation of DC as one of the priorities for future studies. We listed the currently working versions of our DC for GCS and PR in Table 1 and Table 2. The criteria for GCS were validated at two geographical locations,119,120 while the criteria for PR were validated in one geographical location only.121 These criteria are by no means finalized, and are to be further validated for different populations. Details of our reasons for advocating these DC are set out below.

Table 1. Proposed diagnostic criteria for Gianotti-Crosti syndrome.114,115.

| A patient is diagnosed as having Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS, or papular acrodermatitis) if: |

|---|

|

| The positive clinical features are: |

|

| The negative clinical features are: |

|

The differential diagnoses are: acrodermatitis enteropathica, erythema infectiosum, erythema multiforme, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, lichen planus, papular urticaria, papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome, and scabies.

Table 2. Proposed diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea.116.

| A patient is diagnosed as having pityriasis rosea if: |

|---|

|

| The essential clinical features are: |

|

| The optional clinical features are: |

|

| The exclusion clinical features are: |

|

Reasons for diagnostic criteria

High dependence on clinical diagnosis

GCS, PR, APE, ER, PPGSS and related exanthems are diagnosed clinically. Serological investigations mainly serve to exclude important differential diagnoses. Underlying factors such as diabetes mellitus or HIV infection should be evaluated if clinically appropriate. Skin scrapings for potassium hydroxide smear and fungal culture might exclude tinea corporis. Dermatoscopic examinations exemplify tiny clinical signs.122 Lesional biopsy is too invasive and unnecessary for most patients with these exanthems. If performed, histopathology and immunohistochemical staining can substantiate, but cannot prove, a viral etiology.123 Clinical photography documents changing signs124 and may provide a platform for telemedicine.125

As investigations only assist in making a diagnosis, we have to depend on the clinical judgment of clinicians, which can vary widely. DC might help unify the reliability of diagnosis by different clinicians.

Clinical features in different populations

For different populations, these rashes can vary in the extensiveness,87,88 distribution,87 color,91 and post-inflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation.87,88 One dermatologist might not be expected to be fully equipped to diagnose all variants of these rashes for different populations. DC would offer dermatologists and other clinicians systematic and objective diagnostic tools for different populations.

Different inclusion and exclusion criteria for different studies

Varying inclusion and exclusion criteria have been adopted in different studies.113 This is most prevalently seen for PR. Most studies exclude rashes likely to be caused by medications,45,73,77,113 but not all.115 Some studies explicitly included patients with atypical rash,73,78,79,114 some studies excluded patients with atypical features (Saveleva and Selinski, unpublished data, 2008) while other studies did not mention whether atypical rashes were included or excluded.115 It is also not known how atypical a rash is to be considered for patients to be excluded.113

The level of invasiveness also varies across the studies for PR. In some studies, lesional biopsy was performed for all patients.114 However, the need for lesional biopsy has been challenged.113 Moreover, compulsory lesional biopsy might lower the rate of recruitment.113 If a DC is used, the patients recruited will be more homogenous, and invasive procedures can be minimized.

For clinical and investigational studies, DC could serve as the basis of the inclusion criteria. Other qualifications such as demographic data can then be added on top of the DC. Not fulfilling the DC would raise concerns for exclusion, with other parameters such as drug intake or pregnancy being inserted as the exclusion criteria.

DC would assist in epidemiological studies and help obtain a homogeneous group of patients for proposed studies. For these studies, it would be logical to consider the DC as a primary endpoint. Otherwise, the collection of patients will be very heterogenic. For studies with diagnoses made by different investigators or clinicians, the sensible application of DC would provide a greater homogeneity among the recruited subjects.

Confusing terminology

GCS was first described in 1967.1–3 The disease qualified as non-relapsing, non-itching, monomorphic erythemato-papular dermatitis limited to the face and limbs… always associated with an acute hepatitis, with hepatitis B antigen in the serum and with a reactive reticulohistiocytic lymphadenitis.121 The initially described children were all anicteric.1–3 However, icteric variants soon emerged122,123 and whether this was the same disease was debatable.124 An attempt was also made to separate Gianotti syndrome with vesicles from Gianotti disease without vesicles.125

On adult cases being reported,126 the term Gianotti disease was adopted to describe adult cases. It was then believed that HBV led to different signs for children and adults.21 In view of this, Gianotti himself clarified that GCS should continue to be known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood,127 thus excluding adults.21,126 He also summarized GCS as an infectious disease of childhood, of low infectivity, fairly widespread, and characterised by: (1) Non-relapsing erythemato-papular dermatitis localised to the face and limbs, lasting about 3 weeks. (2) Paracortical hyperplasia of lymphnodes. (3) Acute hepatitis, usually anicteric, which lasts at least 2 months and may progress to chronic liver disease….127

However, it was later suggested that the term Gianotti-Crosti syndrome should be used for all adult and children patients irrespective of etiology, while Gianotti disease should be used if the cause was HBV infection.19–21

Today, GCS and papular acrodermatitis of childhood are considered synonymous.19–21 For infants, GCS might be used, but infantile papular acrodermatitis is usually preferred. The rash in adults is being called GCS in adults,114,115 with the term adult papular acrodermatitis not usually used.114,115 More confusingly, the vast majority of patients with GCS today do not have acute hepatitis.42–46,114,115

For PR, after the original description by Gibert CM in 1860,4 a similar rash pityriasis circiné et marginé of Vidal was described.4 It was argued whether the latter was a variant of PR merely running a longer course, with fever and larger lesions often localized at the axillae or groins, or whether it was a new clinical entity.4,84,128,129 Another term pityriasis circinata et maculate soon surfaced as a variant, but was later referred to as being synonymous to PR.4 The medical literature today still embraces the entities pityriasis rosea of Vidal,130,131 pityriasis rosea of Gibert,132–136 and pityriasis rosea circinata,137 all being synonymous of PR.

APE was originally described by Taïeb et al. in 1993,8 with ULE first described by Bodemer and de Prost in 1992.138 It was not until 1995 that researchers postulated that APE and ULE were the same disease.17 With this debate still continuing, patients with a variant of ULE, namely UME, have been described.10 UME bears little resemblance to APE, as it is not peri flexural at all. More studies should, therefore, be performed on the symptomatology of APE, ULE, and UME. Until then, we might have to tolerate these confusing terminologies.

There is no confusion in the naming of EP. However, whether EP is a homogenous disease or not is being debated. Owing to a wide range of rashes that differ in their contact history and disease duration, it has been suggested that EP is just a rubbish bin diagnostic label for non-specific viral exanthems.52

The term PPGSS is used whether it is related to HB19EV,53–55 other viruses,56–59,139,140 or other causes such as drugs.141 The nomenclature does not change when PPGSS coexists with other cutaneous diseases142 or in immunocompromised patients.143 However, the wide variation in the number of words and hyphens defies seamless electronic indexing and searches, and standardization is needed.

DC will unify the terminologies of these rashes, making diagnostic labels clear and electronic searches much easier.

Wide spectrum of clinical features

For GCS, apart from anicteric1–3 and icteric122,123 forms, rashes with and without vesicles125 were described. The signs are different for children and adults.21 The size of papules and papulovesicles varies significantly.144 The density of the papulovesicles or papules also varies widely according to the various body parts.145,146

Lymphadenopathy was present in around 30.8% of all patients with GCS.147 When they do exist, there is a wide variation in sites and sizes.148 Hepatomegaly was one of the cardinal features originally described.1–3 However, it was found to be present in only 3.8% of patients in a more recent case series.147 The duration of GCS can be extremely short or long. Although most children recover in 2-12 weeks, durations of five days and up to six months have been reported,148 leading to suspicions of whether the same disease is being described; Gianotti mentioned about three weeks.127 These variations make differentiation between GCS and its differential diagnoses a challenging task.114,115 It is believed that it is not possible to reliably differentiate GCS clinically, whether it is due to HBV infection or not.149 However, concomitant cutaneous signs of HBV infection complicate the clinical picture.150–152

For PR, the rash morphology can be vesicular,153–157 purpuric,157,158 hemorrhagic,159 or urticarial.160 The lesions can be gigantic or papular in size.161 The distribution is highly variable, with the classical rash affecting mainly the trunk and proximal aspects of all four extremities symmetrically, and variants with distal extremities being affected most (PR inversus),162 restricted to the shoulders and the hips (limb-girdle PR),163 or unilateral,164,165 The number of lesions in PR can be at the extremes, known as localized PR with only 1–2 lesions166 and papular PR with hundreds of lesions.161 Involvement of special sites, such as the scalp,128 eyelids,128 penis,129 and oral cavity,167,168 defy easy diagnosis.

For APE, the lesions can be strictly asymmetrical118 or nearly symmetrical.169 Most rashes, being peri flexural, do not touch the mid-line. However, variants can touch the midline,170 Lesions can be morbilliform, eczematous, a mixture of both,171 lichenoid,118 or scaly.172 Associated axillary lymphadenopathy can range from severe173 to almost undetectable.118

Distribution of lesions in EP could range from diffuse to fairly localized.50,52 Lesions might be angioma-like174,175 or telangiectasialike.50 They can be blanchable176 or not blanchable.50 A halo surrounding individual lesions is classical,50 although it is absent in some cases.

For PPGSS, concomitant oral ulcers are considered classical. However, these can be completely absent.177,178 The oropharynx could be swollen with a risk of asphyxia,179 leading to a suggestion that PPGSS is not merely a cutaneous eruption. Involvements of the lips, chin, perioral regions, and neck are also highly variable.14,179–181 It is said that where perioral lesions exist, HB19EV is likely to be involved, although this is not yet generally accepted.180 In any case, perioral lesions can coexist with the slapped-cheek erythema in erythema infectiosum, thus confusing the dividing line between the two.180 Atypical variants include a unilateral distribution,182 involvements of the buttocks, genital, and axillary regions,183,184 and large haemorrhagic bullae progressing to cutaneous necrosis and skin ulcerations.185–187 Post-morbid states are usually scar-free,14 but thick black eschars have been reported.185

With the wide variation in the manifestations, diagnosis is challenging, and is highly dependent on the individual experience of the clinicians. DC would make diagnoses more reliable.

Clinical audits

With DC, clinical audits for these rashes can be validly performed to evaluate the standard of medical care.108,188 Changes can be made based on findings of the audits to improve the quality of care. The standards in making a diagnosis189,190 and the standard of the laboratories in substantiating or refuting the diagnoses191,192 can also be conducted and reported. This is possible only when there is a high homogeneity among the patients.

Clinical decisions

Let us examine a hypothetical case of a boy with suspected PPGSS being admitted into the pediatric ward. He may53–55 or may not56–59,193 be suffering from HB19EV infection. Serological and polymerase chain reaction investigations would be arranged, the results of which would be available three days later. Pediatricians and dermatologists have different opinions concerning diagnosis, a well-documented scenario.194

To what extent should the boy be isolated before the laboratory results are available? A nurse serving the ward is now 12-weeks pregnant. She might contract the virus while discharging her usual clinical duties,195 with risks of spontaneous abortion and fetal abnormalities.196,197 Should she be reversely isolated, or how long should she be granted leave? Expertise from many different sources offer a response to these questions, but it is important to consider whether it is valid to apply a diagnostic label of PPGSS in the first place. DC could hasten and facilitate this process.

Disease surveillance

From community and public health perspectives, surveillance of these rashes is important as the viral etiologies, clinical significance, and the rates of complications are still unclear.198–200 HB19EV infection, for example, might lead to erythema infectiosum, PPGSS, or other clinical presentations. Asymptomatic virus shedding is common.201 Its significance might be lower for Caucasian populations. For populations with high prevalence of congenital hemoglobinopathies, namely thalassemias, sickle-cell disease, or congenital spherocytosis, a rise in the incidence of PPGSS might signify escalating prevalence of HB19EV infection in the community202 and, therefore, actions might have to be taken to detect and prevent aplastic anemia.

Limitations and pitfalls

First and foremost, clinical experience is a valuable attribute of the clinician in whichever branch of medicine he is practising. DC cannot replace the clinical acumen of clinicians. For some clinicians, making spot diagnoses not referring to DC might be easier. Some clinicians might apply the DC improperly and come to the wrong conclusions. On the other hand, the clinical acumen of some experienced clinicians might benefit from incorporating DC.

Clinicians should not depend entirely on DC in the face of incongruent clinical signs, when investigation results are incompatible, and if the expected clinical outcomes are not achievable. Otherwise, necessary interventions could be delayed.203,204 Moreover, clinical features of these rashes might alter with time and with different populations. Plans to validate and re-validate DC should be in place before they are put into clinical or academic use. It would also be important if a commission of experts could collaborate in drafting and validating individual DC.

Furthermore, it would be ideal if such DC presents a sizable number of clinical photographs showing both typical and atypical exanthems. Dermatology is virtually an image-based speciality. More images will enhance the learning for non-dermatologists and dermatologists in training. For experienced dermatologists who have probably seen a number of atypical manifestations for each exanthem, the inclusion for more images will help delineate atypical exanthems from other differential diagnoses. One of the limitations in this article is that clinical photos are inadequate, as we are discussing several diseases. We shall tackle this limitation in future publications covering DC of individual diseases.

Patients and parents of patients can be very anxious while dealing with medical terminologies for these rashes34,35 A sheet of DC means nothing to them, and it is the privilege as well as the responsibility of caring physicians to explain the diagnoses to them, communicate openly with them,205 allay their fears35 and heal them.

Conclusions

Rashes suspected to have a viral etiology may be much more common than generally believed. They might cause significant morbidities and have an impact on the quality of life of patients. The associated viral infections may lead to long-term complications which are still unknown to us. Investigations on the viral etiology, immunopathogenesis, descriptive epidemiology, analytical epidemiology, and treatment trials are important. However, diagnoses are often made clinically. Variants of these rashes are common, and the terminologies to describe these rashes are confusing. Published results from different studies are often conflicting.

Different studies adopt highly variable inclusion and exclusion criteria while recruiting patients. This may be part of the reason for the incongruence of published results. The number of patients in many studies is small. The power of their results is low. Studies with few patients might not be published in mainstream dermatology journals, leading to publication bias. Meta-analyses could be conducted to increase the statistical power and thus the clinical significance of these results. Adjustment methods are also in place to minimize publication bias. However, a prerequisite is that the patient populations are homogenous, which they are not for most published studies.

We suggest that future researchers might consider establishing and validating DC for these rashes. Apart from the benefits of DC for clinical and research purposes, these criteria might also prove themselves a resource for clinical audits and disease surveillance. We also encourage ongoing small-scale investigations if the investigators are unable to gather data from large population pools. However, the recruited patients in these investigations should be as homogenous as methodologically feasible with a view towards future aggregation of data with other studies. DC would be one of these methodologically feasible agendas.

References

- 1.Crosti A, Gianotti F. Infantile papular acrodermatitis and lymphoreticulotropic viroses. Minerva Dermatol. 1967;42:264–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gianotti F, Bubola D. Virologic findings in cases of infantile papular acrodermatitis. Minerva Dermatol. 1967;42:280–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jean G, Lambertenghi G, Gianotti F. Ultrastructural aspects of lymph-nodes in infantile papular acrodermatitis. Observation of virus-like particles. Dermatologica. 1968;136:350–61. doi: 10.1159/000254120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Percival GH. Pityriasis rosea. Br J Dermatol. 1932;44:241–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crissey JT. Pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1956;3:801–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)30410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons JM. Pityriasis rosea update: 1986. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelmetti C, Grimalt R, Cambiaghi S, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: report of two new cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:42–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391–3. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70200-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelsohn SS, Verbov JL. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb02700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prose NS, Tope W, Miller SE, Kamino H. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis: a unique childhood exanthem? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:857–9. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70255-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calza AM, Saurat JH. Eruptive pseudoan-giomatosis: a unique childhood exanthem? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:517–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(09)80025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navarro V, Molina I, Montesinos E, et al. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in an adult. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:237–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harms M, Feldmann R, Saurat JH. Papular-purpuric “gloves and socks” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:850–4. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagot M, Revuz J. Papular-purpuric “gloves and socks” syndrome: primary infection with parvovirus B19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:341–2. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone MS, Murph JR. Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a characteristic viral exanthem. Pediatrics. 1993;92:864–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frieden IJ. Childhood exanthems. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1995;7:411–4. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199508000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldari U, Monti A, Righini MG. An epidemic of infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome) due to Epstein-Barr virus. Dermatology. 1994;188:203–4. doi: 10.1159/000247139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono E. Natural history of infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti's disease) with HBsAg subtype adw. Kurume Med J. 1988;35:147–57. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.35.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanzaki S, Kanda S, Terada K, et al. Detection of hepatitis B surface antigen subtype adr in an epidemic of papular acrodermatitis of childhood (Gianotti's disease) Acta Med Okayama. 1981;35:407–10. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toda G, Ishimaru Y, Mayumi M, Oda T. Infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti's disease) and intrafamilial occurence of acute hepatitis B with jaundice: age dependency of clinical manifestations of hepatitis B virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1978;138:211–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayanlowo O, Akinkugbe A, Olumide Y. The pityriasis rosea calendar: a 7 year review of seasonal variation, age and sex distribution. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2010;20:29–31. doi: 10.4314/nqjhm.v20i1.57989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma L, Srivastava K. Clinicoepidemiological study of pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:647–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyriakis KP, Palamaras I, Terzoudi S, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of pityriasis rosea in Athens Greece. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Traore A, Korsaga-Some N, Niamba P, et al. Pityriasis rosea in secondary schools in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799–803. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.7.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venturi C, Zendri E, Medici MC, et al. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in adults: a community outbreak. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:757–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.757-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Augey F, Paillard-Anglaret C, Delattre I, Balme B. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis epidemic in a geriatric setting. Presse Med. 2008;37:431–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruksachatkunakorn C, Apichartpiyakul N, Kanjanaratanakorn K. Parvovirus B19 infection in children with acute illness and rash. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:216–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuang TY, Ilstrup DM, Perry HO, Kurland LT. Pityriasis rosea in Rochester, Minnesota, 1969 to 1978. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:80–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pariser RJ, Pariser DM. Primary care physicians' errors in handling cutaneous disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:239–45. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burns JC, Kushner HI, Bastian JF, et al. Kawasaki disease: A brief history. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E27. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaymak Y, Taner E. Anxiety and depression in patients with pityriasis rosea compared to patients with tinea versicolor. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:367–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuh AA, Chan HH. Effect on quality of life in patients with pityriasis rosea: is it associated with rash severity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:372–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chuh AA. Quality of life in children with pityriasis rosea: a prospective case control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:474–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2003.20603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehsani A, Esmaily N, Noormohammadpour P, et al. The comparison between the efficacy of high dose acyclovir and erythromycin on the period and signs of pitiriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:246–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.70672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amer A, Fischer H. Azithromycin does not cure pityriasis rosea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1702–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, et al. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:241–4. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gianotti F. Papular acrodermatitis of childhood. An Australia antigen disease. Arch Dis Child. 1973;48:794–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.48.10.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishimaru Y, Ishimaru H, Toda G, et al. An epidemic of infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti's disease) in Japan associated with hepatitis-B surface antigen subtype ayw. Lancet. 1976;1:707–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)93087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colombo M, Gerber MA, Vernace SJ, et al. Immune response to hepatitis B virus in children with papular acrodermatitis. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:1103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konno M, Kikuta H, Ishikawa N, et al. A possible association between hepatitis-B antigen-negative infantile papular acrodermatitis and Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Pediatr. 1982;101:222–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spear KL, Winkelmann RK. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. A review of ten cases not associated with hepatitis B. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:891–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.120.7.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chuh AA, Chan HH, Chiu SS, et al. A prospective case control study of the association of Gianotti-Crosti syndrome with human herpesvirus 6 and human herpesvirus 7 infections. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:492–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zawar V, Chuh A. Gianotti-crosti syndrome in India is not associated with hepatitis B infection. Dermatology. 2004;208:87. doi: 10.1159/000075059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1995.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, Dupin N. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230–1. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guillot B, Dandurand M. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis arising in adulthood: 9 cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:455–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pérez-Barrio S, Gardeazábal J, Acebo E, et al. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis: study of 7 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:178–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guillot B, Chraibi H, Girard C, et al. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in infant and newborns. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:966–9. doi: 10.1016/s0151-9638(05)79558-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aydinöz S, Karademir F, Süleymanoglu S, et al. Parvovirus B19 associated papular-purpuric gloves-and-socks syndrome. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48:351–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aguilar-Bernier M, Bassas-Vila J, Torné-Gutiérrez JI, et al. Presence of perineuritis in a case of papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome associated with mononeuritis multiplex attributable to B19 parvovirus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:896–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loukeris D, Serelis J, Aroni K, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of pure red cell aplasia and papular-purpuric ‘gloves and socks’ syndrome in parvovirus B-19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:373–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fretzayas A, Douros K, Moustaki M, Nicolaidou P. Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:250–2. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818cb289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Segura Saint-Gerons R, Ceballos Salobreña A, Gutiérrez Torres P, et al. Papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome. Presentation of a clinical case. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vág T, Sonkoly E, Kemény B, et al. Familiar occurrence of papular-purpuric ‘gloves and socks’ syndrome with human herpes virus-7 and human parvovirus B19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:639–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsieh MY, Huang PH. The juvenile variant of papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome and its association with viral infections. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:201–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drago F, Ranieri E, Malaguti F, et al. Human herpesvirus 7 in patients with pityriasis rosea. Electron microscopy investigations and polymerase chain reaction in mononuclear cells, plasma and skin. Dermatology. 1997;195:374–8. doi: 10.1159/000245991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drago F, Ranieri E, Malaguti F, et al. Human herpesvirus 7 in pityriasis rosea. Lancet. 1997;349:1367–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watanabe T, Sugaya M, Nakamura K, Tamaki K. Human herpesvirus 7 and pityriasis rosea. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:288–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kosuge H, Tanaka-Taya K, Miyoshi H, et al. Epidemiological study of human herpesvirus-6 and human herpesvirus-7 in pityriasis rosea. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:795–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drago F, Malaguti F, Ranieri E, et al. Human herpes virus-like particles in pityriasis rosea lesions: an electron microscopy study. Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:359–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watanabe T, Kawamura T, Jacob SE, et al. Pityriasis rosea is associated with systemic active infection with both human herpesvirus-7 and human herpesvirus-6. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:793–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vág T, Sonkoly E, Kárpáti S, et al. Avidity of antibodies to human herpesvirus 7 suggests primary infection in young adults with pityriasis rosea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:738–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, et al. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Offidani A, Pritelli E, Simonetti O, et al. Pityriasis rosea associated with herpesvirus 7 DNA. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:313–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chuh AA, Chiu SS, Peiris JS. Human herpesvirus 6 and 7 DNA in peripheral blood leucocytes and plasma in patients with pityriasis rosea by polymerase chain reaction: a prospective case control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:289–90. doi: 10.1080/00015550152572958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karabulut AA, Koçak M, Yilmaz N, Eksioglu M. Detection of human herpesvirus 7 in pityriasis rosea by nested PCR. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:563–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canpolat Kirac B, Adisen E, Bozdayi G, et al. The role of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus in the aetiology of pityriasis rosea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prantsidis A, Rigopoulos D, Papatheodorou G, et al. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 in the skin of patients with pityriasis rosea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:604–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chuh AA, Chan PK, Lee A. The detection of human herpesvirus-8 DNA in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in adult patients with pityriasis rosea by polymerase chain reaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:667–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chuh AA. The association of pityriasis rosea with cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19 infections - a prospective case control study by polymerase chain reaction and serology. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chuh AA, Chan HH. Prospective case-control study of chlamydia, legionella and mycoplasma infections in patients with pityriasis rosea. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rivers TM. Viruses and Koch's postulates. J Bacteriol. 1937;33:1–12. doi: 10.1128/jb.33.1.1-12.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc Royal Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fredericks DN, Relman DA. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch's postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:18–33. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Desnues B, Al Moussawi K, Raoult D. Defining causality in emerging agents of acute bacterial diarrheas: a step beyond the Koch's postulates. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1787–97. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams JV. Déjà vu all over again: Koch's postulates and virology in the 21st century. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1611–4. doi: 10.1086/652406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lowe AM, Yansouni CP, Behr MA. Causality and gastrointestinal infections: Koch, Hill, and Crohn's. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:720–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Demattei C, Zawar B, Lee A, et al. Spatial-temporal case clustering in children with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Systematic analysis led to the identification of a mini-epidemic. Eur J Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;16:159–64. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vollum DI. Pityriasis rosea in the African. Trans St John's Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1973;59:269–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jacyk WK. Pityriasis rosea in Nigerians. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:397–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1980.tb03738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chuang TY, Ilstrup DM, Perry HO, Kurland LT. Pityriasis rosea in Rochester, Minnesota, 1969 to 1978. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:80–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Souza Sittart JA, Tayah M, Soares Z. Incidence pityriasis rosea of Gibert in the Dermatology Service of the Hospital do Servidor Público in the state of São Paulo. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1984;12:336–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ahmed MA. Pityriasis rosea in the Sudan. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:184–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb02214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olumide Y. Pityriasis rosea in Lagos. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:234–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheong WK, Wong KS. An epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea in Middle Road Hospital. Singapore Med J. 1989;30:60–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harman M, Aytekin S, Akdeniz S, Inalöz HS. An epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea in the Eastern Anatolia. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:495–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1007412330146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nanda A, Al-Hasawi F, Alsaleh QA. A prospective survey of pediatric dermatology clinic patients in Kuwait: an analysis of 10,000 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:6–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.99002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tay YK, Goh CL. One-year review of pityriasis rosea at the National Skin Centre, Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999;28:829–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chuh A, Lee A, Zawar V, et al. Pityriasis rosea – an update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:311–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scott LA, Stone MS. Viral exanthems. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Messenger AG, Knox EG, Summerly R, et al. Case clustering in pityriasis rosea: support for role of an infective agent. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:371–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6313.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chuh A, Lee A, Molinari N. Case clustering in pityriasis rosea – a multi-center epidemiologic study in primary care settings in Hong Kong. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:489–93. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nakamura Y, Yanagawa I, Kawasaki T. Temporal and geographical clustering of Kawasaki disease in Japan. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;250:19–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chuh A, Molinari N, Sciallis G, et al. Temporal case clustering in pityriasis rosea – a regression analysis on 1379 patients in Minnesota, Kuwait and Diyarbakýr, Turkey. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:767–71. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R. The need to reform our assessment of evidence from clinical trials: a commentary. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dauendorffer JN, Dupuy A. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome associated with herpes simplex virus type 1 gingivostomatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:450–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kang NG, Oh CW. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome following Japanese encephalitis vaccination. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:459–61. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ting PT, Barankin B, Dytoc MT. Gianotti- Crosti syndrome in two adult patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:121–5. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nelson JS, Stone MS. Update on selected viral exanthems. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:359–64. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Baden HP, Provan J. Sunlight and pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:377–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arndt KA, Paul BS, Stern RS, Parrish JA. Treatment of pityriasis rosea with UV radiation. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:381–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Michalowski R, Chibowska M. Treatment of pityriasis rosea with streptomycin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1968;48:355–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Drago F, Rebora A. Treatments for pityriasis rosea. Skin Therapy Lett. 2009;14:6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005068. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005068.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Villarama C, Lansang P. The efficacy of erythromycin stearate in pityriasis rosea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Zhu 1992. Available from: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/…/pdf.

- 110.Lazaro-Medina A, Villena-Amurao C, Dy-Chua NS, et al. A clinicohistopathologic study of a randomized double-blind clinical trial using oral dexchlorpheniramine 4mg, betamethasone 500mcg and betamethasone 250mg with dexchlor-pheniramine 2mg in the treatment of pityriasis rosea: a preliminary report. J Phil Dermatological Society. 1996;5:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhu QY. The curative effect observation of Glycyrrhizin for pityriasis rosea. Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 1992;21:43. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Borm GF, den Heijer M, Zielhuis GA. Publication bias was not a good reason to discourage trials with low power. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hayashino Y, Noguchi Y, Fukui T. Systematic evaluation and comparison of statistical tests for publication bias. J Epidemiol. 2005;15:235–43. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chuh AA. Diagnostic criteria for Gianotti-Crosti syndrome: a prospective case-control study for validity assessment. Cutis. 2001;68:207–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chuh A, Lee A, Zawar V. The diagnostic criteria of Gianotti-Crosti syndrome: are they applicable to children in India? Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:542–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chuh AA. Diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea: a prospective case control study for assessment of validity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:101–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00519_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chuh AA. Collarette scaling in pityriasis rosea demonstrated by digital epiluminescence dermatoscopy. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:88–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chan PK, To KF, Zawar V, et al. Asym-metric periflexural exanthem in an adult. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:320–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kaliyadan F, Manoj J, Venkitakrishnan S, Dharmaratnam AD. Basic digital photography in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:532–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.44334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tsang MW, Kovarik CL. The role of dermatopathology in conjunction with teledermatology in resource-limited settings: lessons from the African Teledermatology Project. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:150–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gianotti F. Infantile papular acrodermatitis. Acrodermatitis papulosa and the infantile papulovesicular acrolocalized syndrome. Hautarzt. 1976;27:467–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Monari E, Chiodo F. Crosti-Gianotti infantile papular acrodermatitis with icteric hepatitis. G Mal Infett Parassit. 1971;23:275–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ulivelli A. Crosti-Gianotti infantile papular acrodermatitis with jaundice. Observations on 2 cases. Minerva Pediatr. 1972;24:2098–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schliró G, Fischer A, Russo A. Letter: HBAG in papular acrodermatitis of childhood. Br Med J. 1975;1:395. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5954.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Endo M, Mori H, Morishima T. On infantile papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti disease) and infantile papular-similvesicular acrodermatitis (Gianotti syndrome) J Dermatol. 1975;2:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1975.tb00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Claudy AL, Ortonne JP, Trepo C, Bugnon B. Adult papular acrodermatitis (Gianotti's disease). Report of 3 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1977;104:190–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gianotti F. Papular acrodermatitis of childhood and other papulo-vesicular acro-located syndromes. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb03569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Klauder JV. Pityriasis rosea with particular reference to its unusual manifestations. JAMA. 1924;82:178–83. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sarkany I, Hare PJ. Pityriasis rotunda (pityriasis circinata) Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:223–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb14514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zawar V, Godse K. Annular groin eruptions: pityriasis rosea of vidal. Int J Dermatol; 2011;50:195–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zawar V, Kumar R. Multiple recurrences of pityriasis rosea of Vidal: a novel presentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:114–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bachmann MA, Leuenberger M, Stanga Z. What is your diagnosis? Pityriasis rosea Gibert. Praxis. 2007;96:1895–6. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157.96.48.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hofer T. Myerson nevus as a primary patch of Gibert pityriasis rosea. A case report. Hautarzt. 2002;53:338–41. doi: 10.1007/s001050100268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gjenero-Margan I, Vidovic R, Drazenovic V. Pityriasis rosea Gibert: detection of Legionella micdadei antibodies in patients. Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;11:459–62. doi: 10.1007/BF01721233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Feinstein A, Kahana M. Pityriasis rosea of Gibert. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1260–1. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ishibashi A, Ueda I, Fujita K. Pityriasis rosea Gibert and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Dermatol. 1985;12:97–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1985.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Abe M, Hashimoto C, Hasegawa M, et al. Pityriasis circinata Toyama successfully treated with high-concentration tacalcitol ointment. J Dermatol. 2005;32:153–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693–6. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70239-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ongrádi J, Becker K, Horváth A, et al. Simultaneous infection by human herpesvirus 7 and human parvovirus B19 in papular-purpuric gloves-and-socks syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:672. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Seguí N, Zayas A, Fuertes A, Marquina A. Papular-purpuric ‘Gloves-and-Socks’ syndrome related to rubella virus infection. Dermatology. 2000;200:89. doi: 10.1159/000018333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.van Rooijen MM, Brand CU, Ballmer-Weber BK, et al. Drug-induced papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome. Hautarzt. 1999;50:280–3. doi: 10.1007/s001050050902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hakim A. Concurrent Henoch-Schönlein purpura and papular-purpuric gloves-and-socks syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29:131–2. doi: 10.1080/030097400750001969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ghigliotti G, Mazzarello G, Nigro A, et al. Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome in HIV-positive patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:916–7. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.103263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ehringhaus C, Happle R, Dominick HC, Brune KH. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. HBsAG-negative papular acrodermatitis, an infantile papulovesicular acrolocalized syndrome. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1985;133:111–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Weinerman HC, Weisman SJ, Cates KL. Transient lymphoblastosis and thrombo-cytopenia in Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:185–7. doi: 10.1177/000992289002900310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Chuh AA. Truncal lesions do not exclude a diagnosis of Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:215–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2003.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Taïeb A, Plantin P, Du Pasquier P, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome: a study of 26 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb06219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chuh AAT. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome – the extremes in rash duration. Int Pediatr. 2002;17:45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Caputo R, Gelmetti C, Ermacora E, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome: a retrospective analysis of 308 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:207–10. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70028-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Han SH. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:403–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Zurn A, Schmied E, Saurat JH. Cutaneous manifestations of infection due to hepatitis B virus. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 1990;79:1254–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Baig S, Alamgir M. The extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis B virus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:451–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Anderson CR. Dapsone treatment in a case of vesicular pityriasis rosea. Lancet. 1971;2:493. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Garcia RL. Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Griffiths A. Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1733–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Friedman SJ. Pityriasis rosea with erythema multiforme-like lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:135–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Bari M, Cohen BA. Purpuric vesicular eruption in a 7-year-old girl. Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1497–501. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1990.01670350111020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Verbov J. Purpuric pityriasis rosea. Dermatologica. 1980;160:142–4. doi: 10.1159/000250488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Paller AS, Esterly NB, Lucky AW, et al. Hemorrhagic pityriasis rosea: an unusual variant. Pediatrics. 1982;70:357–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Chuh A, Zawar V, Lee A. Atypical presentations of pityriasis rosea: case presentations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Bernardin RM, Ritter SE, Murchland MR. Papular pityriasis rosea. Cutis. 2002;70:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Gibney MD, Leonardi CL. Acute papulosquamous eruption of the extremities demonstrating an isomorphic response. Inverse pityriasis rosea (PR) Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:651–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Truhan AP. Pityriasis rosea. Am Fam Physician. 1984;29:193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Little EG. Pityriasis Rosea with some Unusual Characters. Proc R Soc Med. 1914;7:274–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Osawa A, Haruna K, Okumura K, et al. Pityriasis rosea showing unilateral localization. J Dermatol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01044.x. doi: 10.1111/ j.1346-8138.2010.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Ahmed I, Charles-Holmes R. Localized pityriasis rosea. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:624–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Vidimos AT, Camisa C. Tongue and cheek: oral lesions in pityriasis rosea. Cutis. 1992;50:276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Tunnessen WW., Jr Picture of the month. Pityriasis rosea. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1441–2. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160120109030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Mørtz CG, Bygum A. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema of childhood. Ugeskr Laeger. 2000;162:2050–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Arun B, Salim A. Transient linear eruption: asymmetric periflexural exanthem or blaschkitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:301–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979–84. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Strom K, Mempel M, Fölster-Holst R, Abeck D. Unilateral latero-thoracic exanthema in childhood. Clinical characteristics and diagnostic criteria in 5 patients. Hautarzt. 1999;50:39–41. doi: 10.1007/s001050050862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Cambon L, Bonafé JL. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in an adult renal transplant recipient. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:55–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Larralde M, Ballona R, Correa N, et al. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:76–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Pitarch G, Torrijos A, García-Escrivá D, Martínez-Menchón T. Eruptive pseudoan-giomatosis associated to cytomegalovirus infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:455–6. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Feldmann R, Harms M, Saurat JH. Papular-purpuric ‘gloves and socks’ syndrome: not only parvovirus B19. Dermatology. 1994;188:85–7. doi: 10.1159/000247106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Allegue F, Morano-Amado L, Rodríguez A, Fachal C. Fever, stomatitis, and cutaneous eruption on the hands and feet. “Gloves and socks” papular purpuric syndrome. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1996;14:271–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Smith PT, Landry ML, Carey H, et al. Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome associated with acute parvovirus B19 infection: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:164–8. doi: 10.1086/514629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Harel L, Straussberg I, Zeharia A, et al. Papular purpuric rash due to parvovirus B19 with distribution on the distal extremities and the face. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1558–61. doi: 10.1086/344773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Sato A, Umezawa R, Kurosawa R, Kajigaya Y. Human parvovirus B19 infection which first presented with petechial hemorrhage, followed by papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome and erythema infectiosum. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2002;76:963–6. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.76.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Martínez G MJ, Elgueta N A. A family outbreak of parvovirus B19 atypical exanthemas: report of two cases. Rev Med Chil. 2008;136:620–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Foti C, Bonamonte D, Conserva A, et al. Erythema infectiosum following generalized petechial eruption induced by human parvovirus B19. New Microbiol. 2006;29:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Segura Saint-Gerons R, Ceballos Salobreña A, Gutiérrez Torres P, et al. Papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome. Presentation of a clinical case. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Passoni LF, Ribeiro SR, Giordani ML, et al. Papular-purpuric “gloves and socks” syndrome due to parvovirus B19: report of a case with unusual features. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001;43:167–70. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652001000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Higashi N, Fukai K, Tsuruta D, et al. Papular-purpuric gloves-and-socks syndrome with bloody bullae. J Dermatol. 2002;29:371–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Frühauf J, Massone C, Müllegger RR. Bullous papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome in a 42-year-old female: molecular detection of parvovirus B19 DNA in lesional skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:691–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Brown RB, Bell L. Patient-centered quality improvement audit. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2005;18:92–102. doi: 10.1108/09526860510588124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Redfern S, Christian S. Achieving change in health care practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9:225–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Horváth AR. Evidence-based laboratory medicine. Orv Hetil. 2003;144:869–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Plebani M. The clinical importance of laboratory reasoning. Clin Chim Acta. 1999;280:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Pruksachatkunakorn C, Apichartpiyakul N, Kanjanaratanakorn K. Parvovirus B19 infection in children with acute illness and rash. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:216–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Auvin S, Imiela A, Catteau B, et al. Paediatric skin disorders encountered in an emergency hospital facility: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:451–4. doi: 10.1080/00015550410021448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Bell LM, Naides SJ, Stoffman P, et al. Human parvovirus B19 infection among hospital staff members after contact with infected patients. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:485–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908243210801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.de Jong EP, Walther FJ, Kroes AC, Oepkes D. Parvovirus B19 infection in pregnancy: new insights and management. Prenat Diagn. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pd.2714. 10.1002/pd.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Lamont RF, Sobel JD, Vaisbuch E, et al. Parvovirus B19 infection in human pregnancy. BJOG. 2011;118:175–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Campagna M, Bacis M, Belotti L, et al. Exanthemic diseases (measles, chickenpox, rubella and parotitis). Focus on screening and health surveillance of health workers: results and perspectives of a multicenter working group. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2010;32:298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Castelli F, Urbinati L. Exanthemic diseases: clinical and epidemiologic aspects. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2010;32:292–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Vega Alonso T, Gil Costa M, Rodríguez Recio MJ, de la Serna Higuera P. Incidence and clinical characteristics of maculopapular exanthemas of viral aetiology. Aten Primaria. 2003;32:517–23. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6567(03)70781-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Gonçalves G, Correia AM, Palminha P, et al. Outbreaks caused by parvovirus B19 in three Portuguese schools. Euro Surveill. 2005;10:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Kellermayer R, Faden H, Grossi M. Clinical presentation of parvovirus B19 infection in children with aplastic crisis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1100–1. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000101783.73240.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Schattner A, Magazanik N, Haran M. The hazards of diagnosis. QJM. 2010;103:583–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Mehta A. The how (and why) of disease registers. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Beach MC, Roter DL, Wang NY, et al. Are physicians' attitudes of respect accurately perceived by patients and associated with more positive communication behaviors? Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]