Abstract

Release of neurotransmitters and hormones by calcium-regulated exocytosis is a fundamental cellular process that is disrupted in a variety of psychiatric, neurological, and endocrine disorders. As such, there is significant interest in targeting neurosecretion for drug and therapeutic development, efforts that will be aided by novel analytical tools and devices that provide mechanistic insight coupled with increased experimental throughput. Here, we report a simple, inexpensive, reusable, microfluidic device designed to analyze catecholamine secretion from small populations of adrenal chromaffin cells in real time, an important neuroendocrine component of the sympathetic nervous system and versatile neurosecretory model. The device is fabricated by replica molding of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) using patterned photoresist on silicon wafer as the master. Microfluidic inlet channels lead to an array of U-shaped “cell traps”, each capable of immobilizing single or small groups of chromaffin cells. The bottom of the device is a glass slide with patterned thin film platinum electrodes used for electrochemical detection of catecholamines in real time. We demonstrate reliable loading of the device with small populations of chromaffin cells, and perfusion / repetitive stimulation with physiologically relevant secretagogues (carbachol, PACAP, KCl) using the microfluidic network. Evoked catecholamine secretion was reproducible over multiple rounds of stimulation, and graded as expected to different concentrations of secretagogue or removal of extracellular calcium. Overall, we show this microfluidic device can be used to implement complex stimulation paradigms and analyze the amount and kinetics of catecholamine secretion from small populations of neuroendocrine cells in real time.

Introduction

Release of neurotransmitters and hormones by calcium-regulated exocytosis is a fundamental cellular process that is disrupted in a variety of psychiatric, neurological, and endocrine disorders. Therefore, there is considerable interest in drug and therapeutic development that target neurosecretion, efforts that will be aided by novel quantitative analytical tools and devices that provide mechanistic insight coupled with increased experimental throughput. Adrenal chromaffin cells, an important neuroendocrine component of the sympathetic nervous system, release catecholamines, neuropeptides, and other hormones to help maintain homeostatic function and appropriate responses to acute stress (e.g. the “fight-or-flight” response). Chromaffin cells are also a versatile model used to investigate the mechanisms and regulation of neurosecretion 1–5.Typically, this involves two general approaches. The first is to measure secretion from large populations of cells (several hundred thousand) plated in tissue culture dishes and incubated with secretagogues for 5–30 minutes. Following stimulation (or at discrete time points during stimulation) the bath solution is sampled for subsequent offline detection of the released catecholamines. While providing useful information, this approach is limited by the need for relatively large numbers of cells, and it lacks temporally resolved information. Alternatively, single cell approaches such as patch clamp electrophysiology (monitoring changes in membrane capacitance)and various imaging techniques can be used6–11. Electrochemical approaches such as carbon fiber amperometry and cyclic voltammetry are particularly well suited to detect oxidizable catecholamines12, and can resolve transmitter release from individual vesicular fusion events 13–16. These techniques provide exquisite sensitivity and temporal resolution but are time-consuming (low throughput) and require both expensive equipment and highly trained personnel. Ongoing efforts to increase the capacity of such approaches using arrays of individually addressable electrodes have been reported17–26. However, these still need refinement of the instrumentation, cell trapping strategies, and fluidic control for drug exposures. The large variability in frequency, amplitude, and kinetics of the amperometric spikes (unitary vesicular release events) presents another challenge for data analysis14, 27.

In this paper we report the design and validation of a simple, inexpensive, reusable, microfluidic platform that enables reliable electrochemical detection of catecholamine secretion from small populations of cells (tens to a few hundred cells). Two parallel considerations provided the rationale for taking this approach. First, the collective response of the cell population provides an easy to analyze readout of neurosecretion while maintaining precise quantitative and kinetic information. This will enable rapid and reliable assessment of drugs or other manipulations that might impact neuroendocrine secretion, and complement the efforts of other groups that focus on detailed analysis of unitary release events from single cells. A second goal of our approach is to develop a “sympathoadrenal module” for future reconstitution of physiological “circuits-on-a-chip” (e.g. sympathoadrenal control of cardiomyocyte function). Chromaffin cells form small clusters within the intact adrenal gland, and the close packing density achieved in our devices promotes autocrine/ paracrine communication which helps control catecholamine secretion 28. Thus, we wanted to develop a platform that would maintain this autocrine/paracrine communication (that is lost in individually dispersed cells),and permit easy manipulation of cell density and spacing within the microfluidic chamber.

Methods

Materials and Reagents

Platinum rod (99.95%; 2mm diameter) and titanium rod (99.95%; 2mm diameter) were purchased from Goodfellow Corp., and universal pH buffers from VWR Scientific. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer composed of prepolymer and curing agent (Sylgard184 kit, Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was purchased from Essex Chemical. The NaCl-basal solution used to bathe the cells contained (in mM): 145 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 Glucose, 10 HEPES, 2 CaCl2, pH7.3, osmolarity ~305mOsm. In some experiments nominally calcium free solutions was used, in which case CaCl2 was omitted and 0.1 mM EGTA added to the above solution. To evoke exocytosis, cells were stimulated with a high potassium (60mM) solution, carbachol, or PACAP 38. The high potassium solution consisted of (in mM) 87 NaCl, 60 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 Glucose, 10 HEPES, 2 CaCl2, pH7.3, osmolarity ~ 305mOsm. Carbachol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was prepared as a stock solution (100mM) in sterile water and aliquots were kept refrigerated. Working solutions of carbachol (30–300µM) were prepared by serial dilution in the NaCl-basal solution. PACAP 38 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was prepared as a stock solution (200mM) in sterile water and aliquots were frozen. Aliquots were diluted in NaCl-basal solution to final working concentrations (100 – 300 nM).All chemicals were used as received.

Instrumentation

Thin film electrodes were fabricated on microscope glass substrate using e-beam vacuum evaporation (Inotec Corp) of titanium and platinum from carbon crucible liners (Kurt J. Lesker Company). The deposition rate and the thickness of the films were assessed with the thickness monitor MDC-350 (Maxtek, Inc).

The electrochemical experiments were performed with a CHI model 660A and 1030 potentiostat/galvanostat (CH Instruments, Austin, TX) in a three-electrode configuration. The counter electrode was either a platinum wire (in beaker experiments) or a thin film platinum electrode in microfluidic devices. In all experiments a Dri-Ref-450 from WPI, Inc. was used as the reference electrode (diameter 0.45mm).

An inverted microscope (AXIOVERT 25CFL, Carl Zeiss, Germany) in combination with a color CCD camera (KP-D20BU, Hitachi, Japan) was used to image the microfluidic device and to control cell loading. An upright optical microscope (OLYMPUS BX-41) with a CCD camera (Micropublisher 3.3, QImagine, Canada) was used to monitor the surface of platinum electrodes. A stereomicroscope STEMI 2000-C (Carl Zeiss, Germany) was used to align the thin film electrodes relative to the microfluidic network. In some experiments the flow was maintained using a micro syringe pump controller MICRO-4 (WPI, Sarasota, FL) for flow rates ranging from 0.1 to 30 nL/s.

Electrode fabrication

The conducting electrodes were deposited on glass microscope slides (76mm×25mm×1mm, Fisher Scientific), cleaned in accordance to a standard procedure 29. The electrodes consisted of two layers: a titanium adhesive layer (10 nm) and a platinum working layer (100 nm). Thin film electrodes were formed by e-beam vacuum evaporation of Ti and Pt from carbon crucible liners. During film deposition, the total gas pressure and substrate temperature were maintained at 5×10−6 Torr and 273K respectively. The deposition rate was 0.5 nm/s for Ti films and 1.0 nm/s for Pt films. The Ti and Pt films were deposited in a single process without breaking vacuum. After deposition, each substrate was cut into individual 25mm×25mm chips. The microelectrode configuration was created by patterning the platinum films using standard photolithography with 1µm-thick photoresist (AZ5214-E, Clariant Corp.). The metal was removed using an ion beam etch process in all areas that were not protected by the resist. The photoresist was stripped from the electrodes in an ultrasonic remover bath (AZ400-T, Clariant Corp.) at 70 °C. Finally, the surface was thoroughly cleaned with acetone and distilled water. A schematic cross section and microscope image the micro electrodes are shown in figure 1A, C and D, respectively.

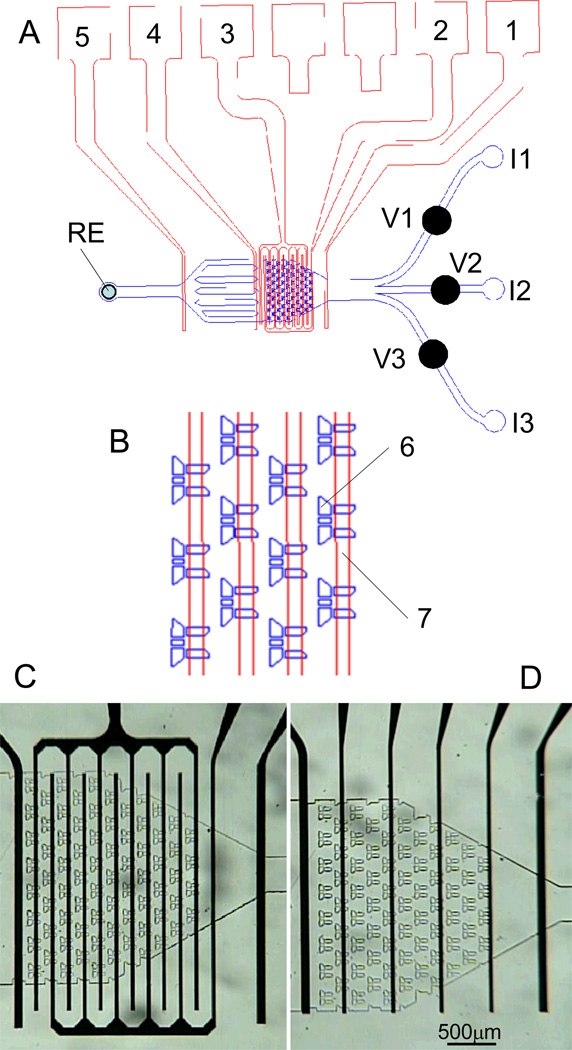

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the microfluidic device to measure catecholamine release from chromaffin cells.

(A) blue – PDMS microfluidic device with channel network; red –microelectrode array; 1, 2, 3, 4 –working electrodes; 5 – counter electrodes; RE – Ag/AgCl reference electrode; V1-V3 mechanical screw valves; I1–I3 - input ports. (B) enlarged view of part of cell trap volume; 6 – cell trap, 7 – Pt electrode; (C) optical image of the cell trap volume with interdigitated Pt electrodes. (D) optical image of the cells trap volume with individual Pt electrodes.

Microfluidic device fabrication

The microfluidic devices were fabricated by replica molding using a patterned photoresist on a silicon wafer as the master, and polydimethylsiloxane(PDMS) as the biocompatible polymer (Sylgard 184, DowCorning, Midland, MI). The master was fabricated by spinning a 25µm layer of photoresist (SU-8 2050, Microchem)on a silicon wafer, followed by a UV light exposure through a metal mask using a contact mask aligner. The photoresist was processed according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. An optional 30min hard bake at 200 °C was performed on a hot plate to increase the durability of the resist. The master was placed in a plastic culture dish and covered by a 8mm thick layer of the PDMS/curing agent mixture at a ratio of 10:1 by weight. After curing the elastomer for 5 h at 60 °C, the devices were mechanically separated from the master and cut out. Access holes to the channels were punched with a sharpened stainless steel pipe. Each microfluidic device was manually aligned relative to the electrode using a stereomicroscope, and sealed onto the electrode/glass substrate by autoadhesion.

It is known that in microfluidic devices, small pressure gradients could result in unpredictable flow pattern30. We developed miniature mechanical screw shut-off valves for precise flow control which were described in detail elsewhere31. The valves were fabricated by drilling a pocket hole above the microfluidic channel and inserting an oversized threaded sleeve with screw into the hole. Turning the screw allowed us to compress the PDMS above the channel for closure. Three valves were placed in close proximity to the cell trap volume (CTV) of the device (Fig. 1).

Microfluidic network design

Fig.1 shows the schematic overview of the microfluidic device to measure catecholamine release from chromaffin cells. The device can be divided into three sections. (A) Input section: There are three input ports (I1 - I3) leading to channels of width 275 µm. The mechanical valves (V1 - V3) were inserted over the input channels to control the flow of solutions and secretagogues used to trigger catecholamine release. Chromaffin cells were loaded into the cell trap volume through the I2 port using gravity feed.(B) The cell trap volume (CTV):This section(total volume ~ 100nL) consists of an array of 71 cell traps located in 11 rows spaced at a distance of 45 µm with respect to each other (Fig 1C, D). Rows of the traps are shifted (offset) with respect to each other by half the trap width. The inside of the trap was 55µm×80µm allowing us to capture a maximum of 15 cells in one trap. There are four channels (width 10 µm) on the back edge of the traps for flow stabilization and collection of the effluent from the chromaffin cells (Fig.1B).(C). Output section. In the output section there are several columns with a different shape which prevents the formation of air bubbles. The width of the output channel is 420 µm. The reference electrode (RE)was placed in the output port (diam. 1mm).

The surface of the PDMS microfluidic device was rinsed with methyl alcohol and dried under a stream of nitrogen before assembling. Then the microfluidic device was manually aligned relative to the electrodes with a stereomicroscope, sealed to the glass substrate by auto adhesion and secured with a mechanical clamp. The microfluidic device was detached from the substrate with the sensing electrodes after each experiment, cleaned and reassembled. In this work we used a configuration with two interdigitated electrodes (width 50 µm) and three single electrodes (width 100 µm) (Fig. 1A). The two interdigitated electrodes were used to measure catecholamine concentration in the cell trap volume (electrodes 2 and 3 in Fig 1A). Electrode 4 was located down-stream from the cell trap volume and could also be used to detect catecholamines while the remaining electrodes (1 and 5, Fig 1A) were used as counter electrodes.

Preparation of bovine adrenal chromaffin cells

Adult bovine adrenal glands were obtained from a local slaughterhouse and chromaffin cells were prepared by digestion with collagenase (3 U/ml) followed by density gradient centrifugation based on previously published protocols 32, 33. The isolated cells were differentially plated to obtain relatively pure chromaffin cell cultures. This plating method exploits the difference in adhesion between chromaffin cells and fibroblasts to glass and plastic surfaces 34. 15ml of the isolated cell suspension was plated in a 10cm2 petri dish at a density of 3×106 cells/ml and left to settle overnight (16–18 hours). The following day, chromaffin cells were detached by gentle washing with culture medium, leaving fibroblasts stuck to the bottom of the dish. Chromaffin cells were centrifuged and re-suspended at a density of 0.8–1.0×106 cells/ml for loading into the microfluidic chamber or plated into T-25 culture flasks for use on subsequent days (see below). The culture medium consisted of DMEM/F12 (1:1) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%), L-glutamine (2mM), penicillin/streptomycin (100 unit ml−1/100g ml−1), cytosine arabinoside (10µM) and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (10µM). Any fibroblasts remaining after differential plating were effectively suppressed with cytosine arabinsoside (10µM). Experiments were performed 1–5 days after cell isolation. All tissue culture reagents were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), except fetal bovine serum which was from Hyclone (Logan, UT).

Clumping of cells can block the microfluidic channels so a variety of conditioned were qualitatively assessed to minimize this problem. The first step was to re-suspend cells grown on the T25 culture flasks. This entailed washing the cells (by replacing the culture medium in the flask) followed by gentle trituration. We compared several wash conditions as follows: wash for 1–2 minutes with fresh complete medium (DMEM/F12 + serum); wash for 1–2 minutes with calcium and magnesium free HBSS prior to trituration in the same HBSS; wash for 1–2 minutes with calcium and magnesium free HBSS prior to trituration in complete medium; wash for 1–2 minutes with calcium and magnesium free HBSS containing dilute trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) followed by addition of complete media prior to trituration. The combination of dilute trypsin and trituration was found to provide the best results, although clumping was still obvious. Thus the cell suspension was filtered sequentially through a 40µm cell strainer and 20µm nylon mesh. The cell suspension was centrifuged and re-suspended in NaCl-basal solution at a density of 0.6-0.8×106 cells/ml. It was noted that the cells tend aggregate in clusters again if not used immediately, so the cell suspension was filtered again through a 40µM cell strainer immediately before loading into the device to minimize larger clumps.

Stimulation of chromaffin cells trapped in the microfluidic device

The microfluidic device enables repetitive exchange of three solutions to perfuse the cell trap volume while monitoring catecholamine secretion from chromaffin cells electrochemically. To obtain reproducible results, we established a protocol for catecholamine release measurements: (a) Solutions / drugs were preloaded through the I1 and I3 ports; (b) NaCl-basal solution was loaded through the I2 port and the cell trap volume was thoroughly washed prior to loading of chromaffin cells, again through the I2 port; (c) following cell loading, fresh NaCl-basal solution was loaded through the I2 port and used to thoroughly wash the cells; (d) perfuse the cell trap volume with drug 1 or 2; (e) perfusion (wash) of cell trap volume with NaCl-basal solution; (f) repeat exposure to drug 1 or 2; (g) steps d-f can be repeated many times. For these initial experiments the drug exposure times were ~100s each.

Determination of catecholamines using high performance liquid chromatography

Chromaffin cells were plated in 24-well tissue culture plates at a density of ~ 0.3×106 cells per well. Cells were washed twice with NaCl-basal solution and incubated in this solution for 30 min at ~37 °C. The solution was then removed and replaced with fresh solution containing secretagogues (either 100 µM carbachol or 60mM KCl). After a five-minute stimulation period at ~37 °C the cells were placed on ice, the solution bathing the cells was removed, quickly centrifuged, and a sample added to an equal volume of ice-cold 0.4 M perchloric acid (HClO4). Perchloric acid was added to the tissue culture wells to lyse the cells and extract the non-released catecholamines. The epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine content of the samples was determined by a specific high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay utilizing an Antec Decade electrochemical detector(oxidation potential: 0.7 V) in the Neurochemistry Core of the Vanderbilt Brain Institute. The total cellular content of norepinephrine was roughly half that of epinephrine, and dopamine was found in much lower abundance (ratio relative to epinephrine was 0.49 ± 0.01 for norepinephrine and 0.01 ± 0.0004 for dopamine; n = 13 wells from 4 independent preparations / animals). However, as reported previously 35, 36 a greater fraction of the cellular norepinephrine was released upon stimulation with KCl or carbachol. Thus roughly equal amounts of norepinephrine and epinephrine were secreted from the cells upon secretagogue stimulation (ratio relative to epinephrine was 1.10 ± 0.04 for norepinephrine and 0.019 ± 0.0012 for dopamine; n = 13 wells from 4 independent preparations / animals). These values were used in combination with the calibration of the platinum electrodes to known concentrations of epinephrine / norepinephrine to estimate the concentration of catecholamine secreted from chromaffin cells within the microfluidic device.

Results

Characterization of catecholamine sensitive platinum electrodes

A number of attempts to improve the properties of platinum electrodes using different methods of surface activation and modification have been described37–43. In some cases these have improved parameters such as sensitivity, selectivity, stability, reproducibility, response time, and shelf live, but in other cases parameters remained unchanged or even worsened. Therefore, unmodified platinum thin films still find widespread application as reliable, sensitive, stable, low cost electrochemical sensor material to monitor various biochemical processes. In this study, we used platinum thin film electrodes for the electrochemical detection of catecholamine secretion.

First we characterized the platinum electrodes response to catecholamines using cyclic voltammetry. The glass substrate with a thin film platinum interdigitated electrode (Fig.1A) was placed in a glass beaker filled with NaCl-basal solution, along with a platinum wire (diam. 1mm) counter electrode and a reference electrode (DRI-REF-450). Figure 2A shows the cyclic voltammogram obtained by sweeping the potential from −0.4V to 1.0V at a rate of 100mV/s in the presence of different epinephrine concentrations. The oxidation current increased linearly with epinephrine concentration over a wide range of a potential difference (0.4 – 0.9V). This was repeated using norepinephrine or dopamine. Figure 2B shows the current response at a potential of 0.7V for each of the catecholamines. The current shows a linear dependence on catecholamine concentration (10 - 500 µM), and the slope of these dependencies indicates the sensitivity of the platinum electrodes which are 0.33± 0.01 mA/M (R2=0.992) for epinephrine, 0.17± 0.01 mA/M (R2=0.983) for norepinephrine, and 0.20± 0.01mA/M (R2=0.979) for dopamine with an effective sensing area of 0.72 mm2 for the interdigitated electrode array.

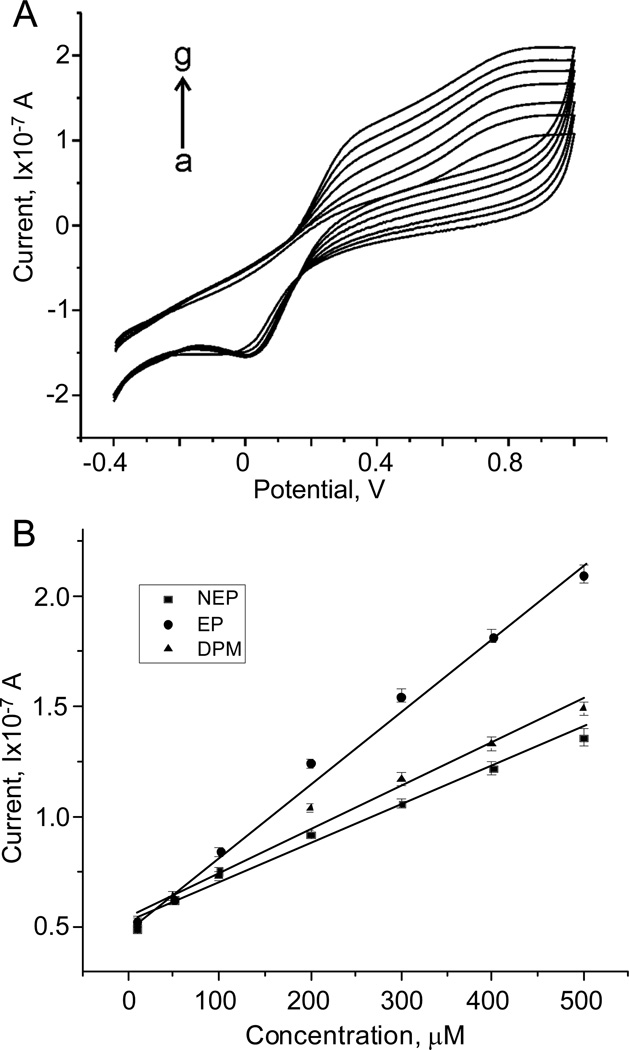

Figure 2. Detection of catecholamines using platinum electrodes in a “beaker experiment”.

(A) cyclic voltamograms using Pt electrodes with various concentrations of epinephrine (0–500 µM) in NaCl-basal solution. Scan rate 100mV/s. (B) Current (at 0.7V) as a function of norepinephrine (NEP), epinephrine (EP) and dopamine (DA) concentration (10–500µM) . The sensitivity of the interdigitated Pt electrode array are 0.33 ± 0.01 mA/M (R2=0.992) for EP, 0.17 ± 0.01 mA/M (R2=0.983) for NEP, and 0.20 ± 0.01 mA/M (R2=0.979) for DA with a sensing area of 0.72 mm2.

Next we characterized the electrodes within the microfluidic device. The glass substrate with the interdigitated platinum electrode array was aligned with the PDMS microfluidic device and clamped to provide mechanical rigidity and to prevent solution leaks. NaCl-basal solutions with three different concentrations of catecholamine were perfused through the device using a micro syringe pump at a flow rate ~ 10 nL/s. The current response was monitored for 200s and then the perfusion solution was switched to a different concentration of catecholamine (Fig 3A, B). We observed a stable oxidation current for each concentration of catecholamine, and the sensitivity of the platinum microelectrodes was comparable to values obtained in the beaker experiments (0.27mA/M for epinephrine and 0.19 mA/M for norepinephrine).

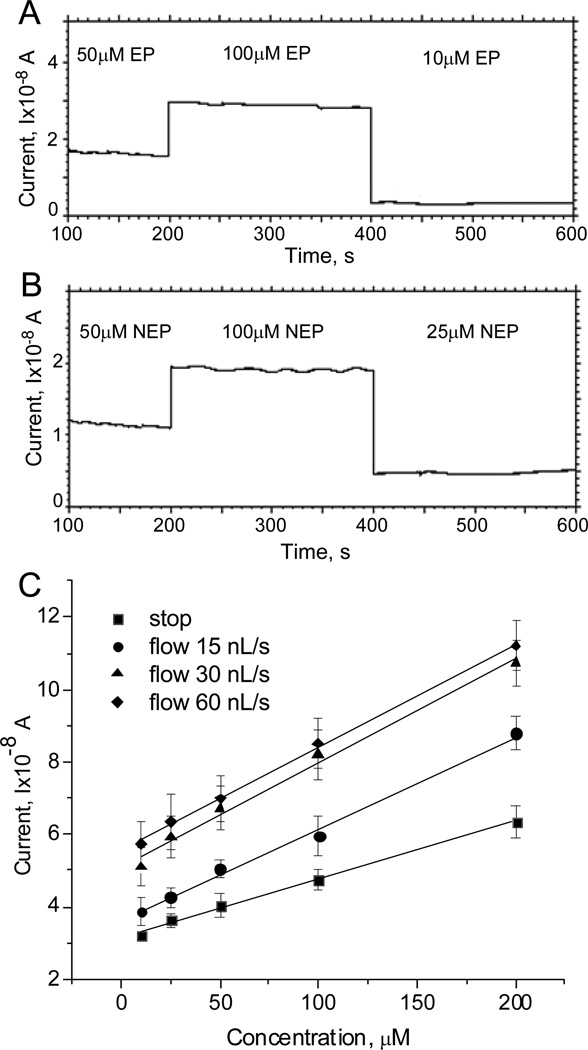

Figure 3. Characterization of platinum electrodes in microfluidic environment.

(A, B) calibration of platinum electrodes in microfluidic device with NaCl-basal solution containing three different concentrations of epinephrine (A) and norepinephrine (B). (C) Dependence of the baseline corrected current on the epinephrine concentration in both “stop” and “flow” conditions. In the “stop” mode, the microfluidic device was filled with a fixed concentration of epinephrine and the mechanical valve was closed to stop solution flow before recording a cyclic voltammogram. In the “flow mode” the valve was not closed and cyclic voltammograms were recorded at a fluid flow rate of 15, 30, or 60nL/s as indicated.

Electrochemical sensing electrodes in microfluidic environments can respond differently during solution flow compared to static conditions44. Thus, we used cyclic voltammetry to investigate the sensitivity of the platinum microelectrode in both “stop” and “flow” mode. In the “stop” mode, the microfluidic device was filled with a fixed concentration of epinephrine in NaCl-basal solution, the channel was closed with the mechanical valve to halt solution flow, and a cyclic voltammogram was recorded. This was repeated for seven different concentrations of epinephrine (10 - 200 µM). In the “flow mode” the valve was not closed and cyclic voltammograms were recorded at fluid flow rates of 15, 30 and 60 nL/s. The response to a given concentration of epinephrine was consistently greater under the “flow” compared to “stop” condition (Fig 3C) and saturated at flow rates larger than approximately 30 nL/s. This could be due to several factors including depletion and the generation of a less steep concentration gradient of catecholamine at the surface of the electrode under stop flow conditions. Under both “stop” and “flow” conditions, the response was linearly related to the epinephrine concentration, and the sensitivity of the electrodes was not significantly different under fluid flow conditions (0.14 ± 0.01mA/M (R2=0.993) in the “stop”, 0.25± 0.01 mA/M (R2=0.997) at 15nL/s, 0.28 ± 0.02 mA/M (R2=0.993) at 30nL/s and 0.26 ± 0.02 mA/M (R2=0.994) at 60 nL/s in the “flow” mode).

Overall, these data demonstrate that the platinum electrodes are well suited for use as electrochemical sensors for catecholamines within the microfluidic device.

Loading of adrenal chromaffin cells into the microfluidic device

In this paper we set-out to develop a cheap, simple, easy to use microfluidic platform to rapidly assess catecholamine secretion from small populations of adrenal chromaffin cells, an important neuroendocrine component of the sympathetic nervous system. One primary requirement was therefore to trap the cells within the device in close apposition to the platinum electrodes. Moreover, the cell trapping volume must be efficiently perfused to enable rapid and reproducible cell exposure to different test solutions and drugs. The arrays of cell traps (Fig 1) provide a means to do this, and since the glass substrate and PDMS device (thickness 6–8 mm) are transparent, the cell trap volume and microfluidic channels can be imaged from both the top and the bottom of the device. This facilitated careful monitoring of the cell loading procedure.

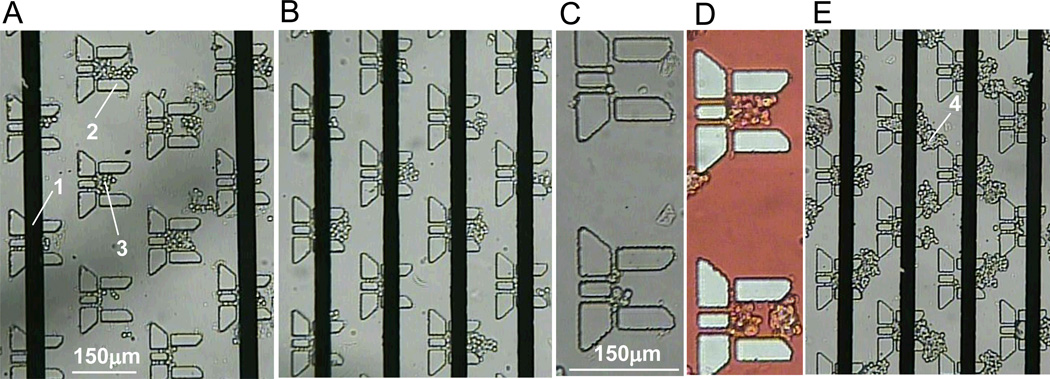

We used primary cultures of bovine adrenal chromaffin cells, which are adherent and can be maintained in tissue culture flasks for 1–2 weeks following isolation from the adrenal gland. Immediately prior to an experiment, the cells were dissociated from the culture flask and resuspended in a small volume of NaCl-basal solution. This cell suspension was washed through the device using gravity driven perfusion via the I2 port (Fig1A) to load chromaffin cells into the cell trap volume. One challenge when using adherent cells is their tendency to clump together when resuspended in solution as this can readily block microfluidic channels and/or impede efficient perfusion of the device. To minimize these clumps, the cells were briefly exposed to a dilute trypsin-EDTA solution (0.05%) followed by gentle trituration and sequential filtering through 40µm and 20µm nylon mesh (see methods). As shown in figure 4, small groups of cells could be captured in most of the traps within the device. We also show an example in which larger clumps of cells accumulated in the spaces between the cell traps (Fig 4E) and disrupted efficient fluid flow through the chamber. Thus, careful monitoring is required for optimal loading of the cells, which typically took 3–5 min. Although not fully assessed, under these conditions the chromaffin cells were viable in the microfluidic device for 5–6 hours, but we aimed to complete our experiments within 1–2 h after cell loading.

Figure 4. Optical images of adrenal chromaffin cells trapped in the NanoPhysiometer.

(A, B) Two examples of chromaffin cells in the traps. (1) platinum electrodes. (2) cell trap. (3) chromaffin cells in the cell trap. In both cases a few chromaffin cells are captured within the cell traps. (C) Higher magnification image of two cells traps with chromaffin cells. (D) Using of food dye (red) for visualization of a perfusion flow. (E) Example showing clumps of cells stuck between (rather than within) the traps (4). These clumps disrupt fluid flow through the device resulting in poor perfusion / washing of the cells.

Stimulation of catecholamine secretion with physiologically relevant secretagogues

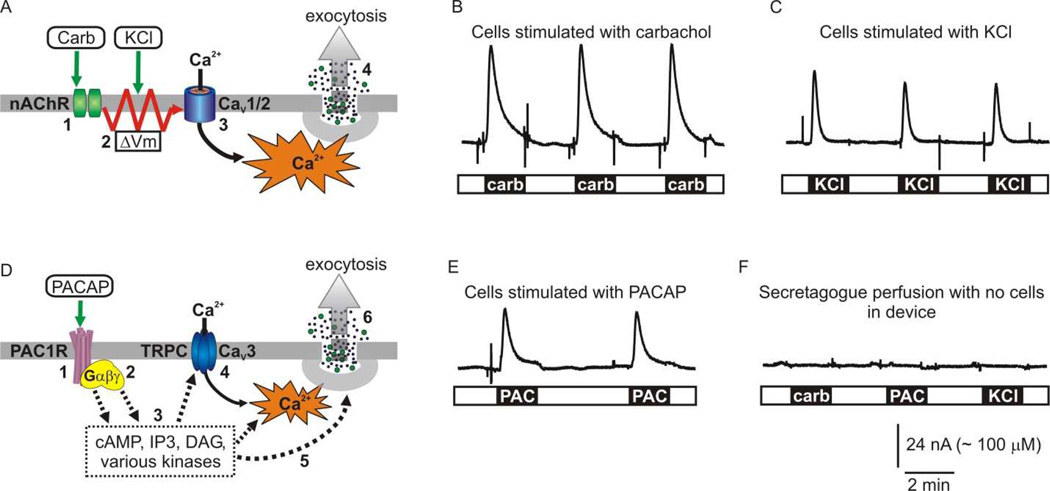

To confirm that the chromaffin cells trapped in the microfluidic device were functionally viable, we investigated the secretory response to physiologically relevant secretagogues. In situ, chromaffin cells are innervated by the splanchnic nerve, which releases acetylcholine. This binds to and opens nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on the chromaffin cells, which in turn depolarize the plasma membrane and open voltage-gated calcium channels (CaV1 and CaV2 channels). Calcium entry through the voltage-gated calcium channels triggers fusion of secretory granules with the plasma membrane and release of catecholamines into the extracellular space. The cholinergic receptor agonist carbachol (an acetylcholine analogue) triggers this chain of events and is a potent secretagogue in chromaffin cells (Fig 5A). Cells trapped in the microfluidic device were repeatedly perfused with carbachol (100 µM),which evoked a robust release of catecholamines detected using the platinum thin film electrodes(Fig 5B). Another commonly used experimental approach to stimulate secretion is to bypass the cholinergic receptors and directly depolarize the plasma membrane by elevating the extracellular concentration of potassium (Fig 5A). Again we found that repeated perfusion with KCl (60 mM) evoked robust catecholamine secretion from cells trapped in the microfluidic device (Fig 5C).

Figure 5. Stimulation and on-chip electrochemical detection of catecholamine secretion by several secretagogues.

(A) Cartoon depicting stimulus-secretion coupling evoked by carbachol and KCl. In situ, acetylcholine released from splanchnic nerve terminals activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) (1) resulting in depolarization of the plasma membrane (2). The depolarization opens CaV1 and CaV2 subtypes of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (3) and the resultant Ca2+ influx triggers Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of secretory granules (4). Stimulation with the cholinergic agonist carbachol (carb) mimics this cascade of events, while elevating extracellular [KCl] directly depolarizes the plasma membrane. (B, C) Examples showing electrochemical detection of catecholamine release in response to 100 µM carbachol (carb) or 60 mM KCl. (D) Cartoon depicting stimulus-secretion coupling evoked by PACAP. PACAP activates the PAC1 G protein coupled receptor (1) which couples to a variety of G proteins (2) and downstream signaling cascades (3). These second messenger cascades result in calcium influx through plasma membrane channels (4) (including CaV3 voltage-gated channels and perhaps TRPC channels), potentiation of the exocytotic machinery (5), and thus hormone secretion (6). (E) Example showing catecholamine release in response to stimulation with 300nM PACAP. (F) Control experiment showing that secretagogues do not elicit electrochemical responses when washed through the device in the absence of chromaffin cells.

Another physiologically relevant secretagogue with a distinct mechanism of action is the neuropeptide PACAP which is released from splanchnic nerve terminals during intense stimulation, as might occur during acute stress. PACAP binds to the PAC1 G-protein coupled receptor and activates multiple downstream signaling pathways. These trigger extracellular calcium entry (perhaps through CaV3 voltage-gated channels and TRPC channels), modulate the exocytotic machinery, and result in exocytosis (Fig 5D). Our data show that the secretory response to PACAP was also maintained in cells trapped in the microfluidic device (Fig 5E). As a control, we confirmed that none of these secretagogues (carbachol, KCl, or PACAP) elicited an electrochemical response when washed through the microfluidic device in the absence of any cells (Fig 5F).

To estimate the concentration of catecholamines released from chromaffin cells within the microfluidic device we used the calibration data reported in figure 3. It is known that chromaffin cells store and release epinephrine, norepinephrine, and to a much lesser extent dopamine. Amperometric recording does not distinguish between these catecholamine species. However, as detailed in the methods section, we used HPLC to calculate the ratio of catecholamines released from chromaffin cell cultures in response to secretagogues and used these values to adjust the calibration of the platinum electrodes. From this information, we estimated that the peak concentration of catecholamines was ~225 µM in the example shown in figure 5B and ~ 170 µM in the example shown in figure 5C.

Validation that evoked catecholamine secretion is physiologically relevant

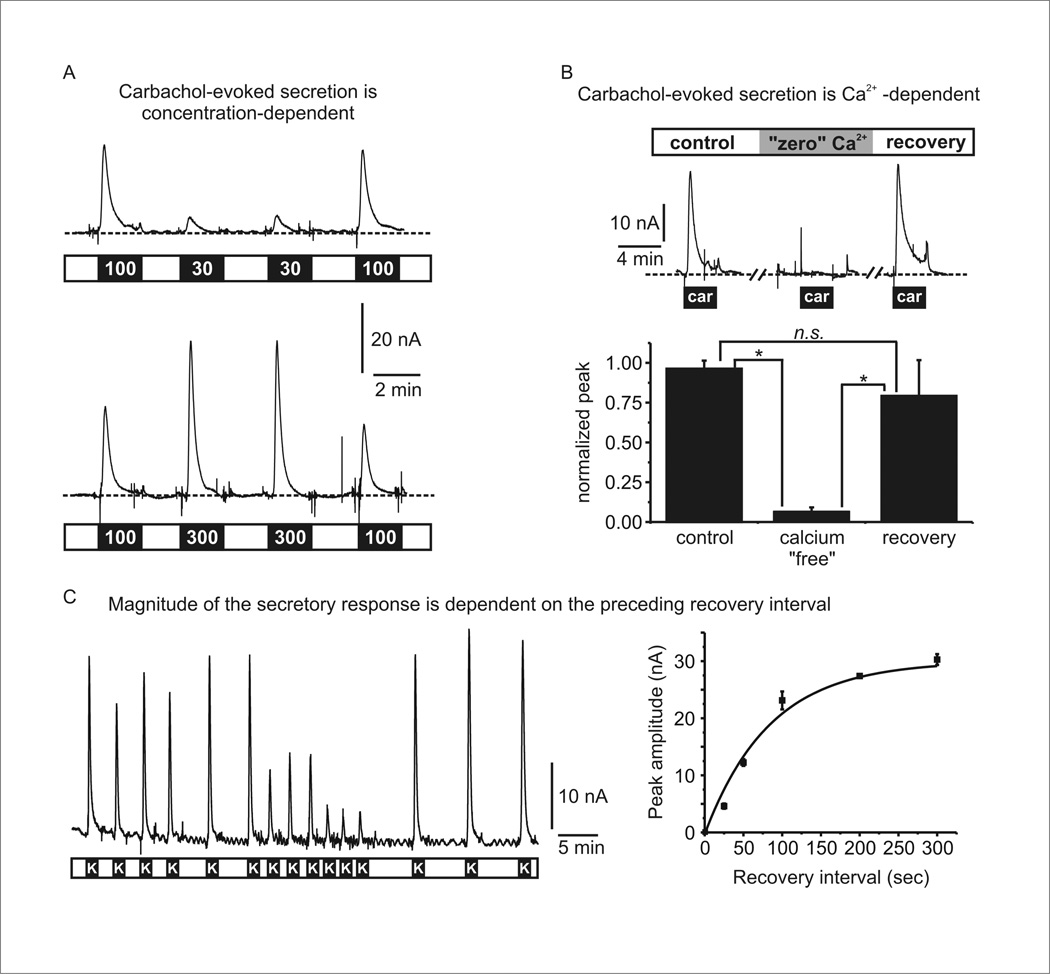

To validate that the stimulus-secretion coupling was physiologically relevant we performed three experiments. First, we confirmed the secretory response to carbachol showed the expected concentration-dependence (Fig 6A). To do so, cells trapped in the device were sequentially stimulated with two concentrations of carbachol. As shown, there was a graded secretory response as the carbachol concentration was increased from 30µM to 300 µM (Fig 6A). Second, we confirmed that the secretion evoked by carbachol was calcium-dependent. As outlined above, calcium entry through voltage-gated calcium channels is the primary trigger for exocytosis (Fig 5A). When calcium was removed from the extracellular solution the evoked catecholamine release was virtually abolished (93 ± 3% inhibition, n = 3, p < 0.05) (Fig 6B), confirming that it was due to calcium-dependent secretion and not cellular damage or other artifacts. Third, we tested the impact of varying the recovery interval between successive rounds of stimulation (Fig 6C). During each exposure to KCl the response rapidly declined, reflecting depletion of fusion competent secretory granules as well as inactivation of voltage-gated calcium channels. Upon washout of KCl the channels recover from inactivation and the pool of fusion competent granules is replenished over a period of tens of seconds. Thus it is expected that if stimuli are applied in quick succession the response will diminish due to incomplete recovery. Indeed, our data show that as the interval between successive KCl applications was decreased the amount of catecholamine secretion decreased (Fig 6C). This further demonstrates that cells trapped in the microfluidic device maintain their physiological responsiveness and predictable secretory behavior over the course of many rounds of stimulation (up to 60 minutes in this case). It also shows the ability to alter the drug exposure paradigm to characterize different facets of the secretory response, in this case the time-course of recovery between successive stimuli.

Figure 6. Validation that evoked catecholamine secretion is physiologically relevant and exhibits predicted behavior.

(A) Concentration-dependent stimulation of catecholamine secretion by carbachol. Two different experiments are shown in which cells were stimulated with 100 µM and 30 µM carbachol (upper panel), or 100 µM and 300 µM carbachol (lower panel). (B) Calcium-dependent stimulation of catecholamine secretion by carbachol. The upper panel shows an example in which cells were stimulated three times by carbachol (100 µM). Prior to and during the second stimulation, the cells were perfused with nominally calcium-free solution which abolished the secretory response to carbachol. The lower panel shows mean data from three independent experiments. Peak amplitude of the current was normalized to the first response in each set of cells (* p < 0.05; repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test). (C) The left panel shows a representative experiment in which cells were repeatedly stimulated by KCl perfusion (100s duration) indicated by the black bars labeled “K”. The recovery interval between each stimulus was varied from 25s to 300s. The right panel plots the response amplitude as a function of the recovery interval. The solid line is an exponential fit to the data.

Repetitive exposure to secretagogues evokes reproducible catecholamine secretion

Having established that chromaffin cells in the microfluidic device respond appropriately to physiological secretagogues, we next tested the reproducibility of secretion in response to multiple rounds of stimulation. This is an important consideration for future efforts to test the ability of drugs or other interventions to acutely alter secretion. Moreover, the on-chip electrochemical monitoring provides high temporal resolution, and thus important information on the time-course of secretion not readily achieved with static incubations. This time-course (i.e. the kinetics of the response) will also depend on the perfusion rate through the device, so it is important to establish if these parameters are stable over multiple rounds of stimulation.

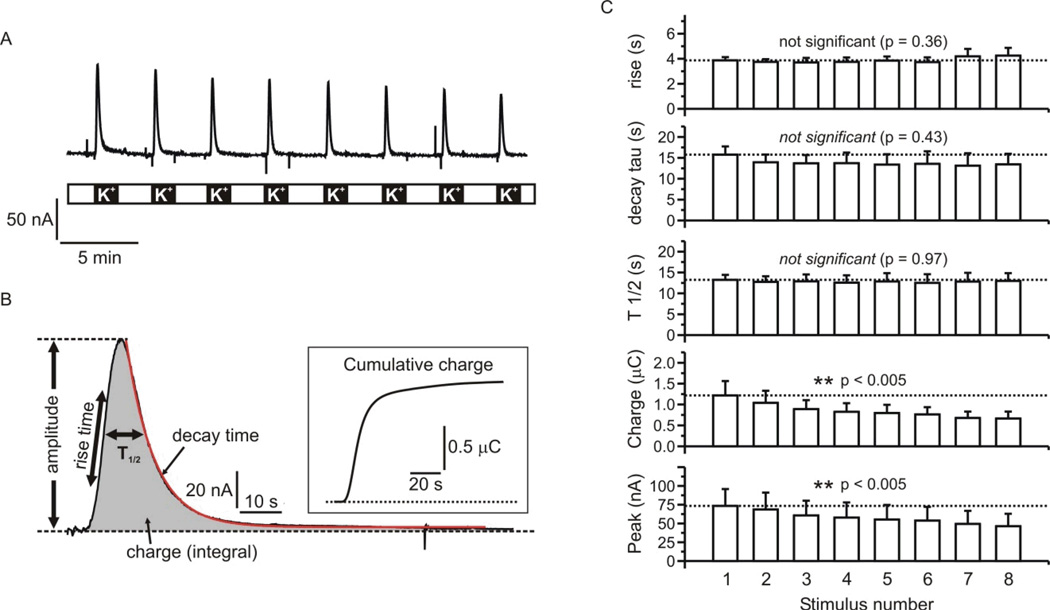

Cells were repeatedly stimulated with 60 mM KCl over the course of ~ 30 minutes (Fig 7A). Each round of stimulation elicited robust catecholamine secretion and we analyzed several parameters of each response as illustrated in figure 7B. The amplitude of the response reflects the concentration of released catecholamines in the device, while the charge is directly proportional to the number of catecholamine molecules oxidized during secretagogue exposure. We also determined the rise time (time from 25% – 75% of peak response), the duration of the response at half maximal amplitude (T1/2), and the decay of the response, which was well fit with a single exponential. The inset to figure 7B shows a plot of the cumulative amperometric charge Vs time, highlighting the ability to provide precise analyses of both the amount and time-course of catecholamine secretion. Figure 7C shows the mean data (from three independent experiments) for various response parameters in each successive round of stimulation. Even with these relatively strong and sustained exposures to KCl, there was robust secretion throughout the experiment. The amount of catecholamine secretion (amplitude and charge) showed a gradual decrease, presumably due to progressive loss of the cellular response (e.g. depletion of releasable catecholamine stores, inactivation of calcium channels). Notably, the kinetics of the response did not change significantly over the course of the experiment.

Figure 7. Repetitive stimulation of catecholamine secretion by KCl.

(A) shows a representative experiment in which cells trapped in the microfluidic device were repeatedly stimulated with 60mM KCl. (B) One of the responses is shown on an expanded scale to illustrate the kinetic resolution and parameters that can be quantified. The inset plots the cumulative charge of the response over time. (C) Mean data from three experiments in which several response parameters are plotted Vs stimulus number. The kinetics of the response to KCl were consistent over the eight rounds of stimulation, with no statistically significant changes in rise time, T1/2, or decay time. The peak amplitude and charge both showed a steady decline over the course of the eight stimuli that was statistically significant (repeated measures ANOVA with post-test for linear trend).

Discussion

We describe an inexpensive, reusable, microfluidic device that provides a real time electrochemical readout of neurosecretion in response to physiologically relevant chemical stimuli. The integrated microfluidic network enables repetitive solution exchanges, while the inherently small volume reduces dilution of the secreted transmitters and conserves resources by minimizing the use of reagents (e.g. novel pharmacological compounds) and cells. The “on-chip” platinum thin film electrodes provide sensitive detection of catecholamines and precise kinetic information on the time-course of secretion. We show that multiple rounds of stimulation result in predictable secretory responses, meaning the same set of cells can serve as their own internal control before and after drug exposure to assess the effects of pharmacological reagents on secretion. Further evidence of this is demonstrated by the reversible changes in secretion in response to different concentrations of carbachol, removal of extracellular calcium, or changes in the recovery interval between successive rounds of stimulation (Fig 6). Future efforts will incorporate additional inlet channels and more sophisticated fluidic control into the microfluidic network to enable rapid and complex drug exposure protocols.

The modular design is readily amenable to scale-up, for example by combining several chambers in parallel to increase overall throughput for pharmacological “screens”. Moreover, because the device is simple and inexpensive to make, it can be readily adapted/ optimized for different situations. For example, the number, size, and spacing of the cell traps within the device can be changed to precisely control cell density to vary the degree of autocrine/paracrine signaling. Similarly, the pattern of thin film platinum electrodes can be changed and reduced in size to record single secretory events. In this paper we focused on use of an interdigitated electrode design, which provides good “coverage” of the entire cell trap volume and thus optimal detection of catecholamine release from the entire cell population. In other situations smaller electrodes could target discrete regions, including individual cell traps, to permit refined spatial discrimination. For example, traps in the “downstream” region of the cell trap volume will be exposed to the secreted material from “upstream” cells. This could be leveraged to investigate the influence of paracrine signaling on secretory output. An extension of this concept is to couple two or more devices together in series. Perfusion solution from the upstream device could be directed to downstream devices to investigate intra-adrenal paracrine signaling. The downstream devices could also contain cells from physiologically relevant target organs to enable detailed cellular analyses of these reconstituted endocrine “circuits-on-a-chip”. One such approach will trap single cardiac myocytes in the downstream device 45–47 to investigate the impact of sympathoadrenal hormones on calcium signaling and contractility.

As already noted, the glass substrate and PDMS device are both optically clear, making it possible to carefully monitor loading of cells into the device. This will also permit optical detection of various physiological parameters to increase the amount of information obtained from each cell preparation, and to provide more mechanistic insight. For example, calcium-sensitive or voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes could be used in parallel with the electrochemical detection of catecholamine secretion. In doing so it will be possible to quickly determine if drugs or interventions that alter secretion do so by altering cellular excitability or calcium signaling.

Conclusions

Overall, we report the design and validation of a simple, inexpensive, reusable, microfluidic platform that enables reliable electrochemical detection of catecholamine secretion from small populations of cells (tens to a few hundred cells). This modular device can form the basis of a platform that will enable rapid assessment of drug effects or other manipulations on neuroendocrine secretion. Implementation of additional optical detection will allow for parallel screening of drug actions on calcium signaling and other pertinent physiological processes. The device will also form the basis of a “sympathoadrenal module” for future reconstitution of physiological “circuits-on-a-chip” to investigate endocrine control of cardiac myocytes and other relevant targets.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ray Johnson, Manager of the Vanderbilt Neurochemistry Core for assistance with high performance liquid chromatography analyses of catecholamines. This work was supported by an Innovative Research Grant from the American Heart Association [Grant 12IRG9070003], and by the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01 NS052446].

References

- 1.Rettig J, Neher E. Science. 2002;298:781–785. doi: 10.1126/science.1075375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aunis D, Langley K. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;167:89–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:581–632. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bader MF, Holz RW, Kumakura K, Vitale N. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;971:178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jewell ML, Currie KPM. In: Modulation of presynaptic calcium channels. Stephens GJ, Mochida S, editors. ch. 5. Springer Publishing; 2013. pp. 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillis KD. Pflugers Arch. 2000;439:655–664. doi: 10.1007/s004249900173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindau M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:1234–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holz RW, Axelrod D. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2008;192:303–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becherer U, Pasche M, Nofal S, Hof D, Matti U, Rettig J. PLoS One. 2007;2:e505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zenisek D, Perrais D. CSH Protoc. 2007;2007 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4863. pdb prot4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betz WJ, Mao F, Smith CB. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:365–371. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ges IA, Currie KPM, Baudenbacher F. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2012;34:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wightman RM, Jankowski JA, Kennedy RT, Kawagoe KT, Schroeder TJ, Leszczyszyn DJ, Near JA, Diliberto EJ, Jr, Viveros OH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10754–10758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosharov EV, Sulzer D. Nat Methods. 2005;2:651–658. doi: 10.1038/nmeth782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borges R, Camacho M, Gillis KD. Acta Physiologica. 2008;192:173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travis ER, Wightman RM. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X, Gillis KD. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2521–2525. doi: 10.1021/ac052037d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spegel C, Heiskanen A, Pedersen S, Emneus J, Ruzgas T, Taboryski R. Lab Chip. 2008;8:323–329. doi: 10.1039/b715107a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Barizuddin S, Shin W, Mathai CJ, Gangopadhyay S, Gillis KD. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2445–2451. doi: 10.1021/ac1033616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barizuddin S, Liu X, Mathai JC, Hossain M, Gillis KD, Gangopadhyay S. Acs Chemical Neuroscience. 2010;1:590–597. doi: 10.1021/cn1000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dittami GM, Rabbitt RD. Lab Chip. 2010;10:30–35. doi: 10.1039/b911763f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carabelli V, Gosso S, Marcantoni A, Xu Y, Colombo E, Gao Z, Vittone E, Kohn E, Pasquarelli A, Carbone E. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;26:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Trouillon R, Lin Y, Svensson MI, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ac4009385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao C, Sun X, Gillis KD. Biomed Microdevices. 2013;15:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s10544-013-9744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim BN, Herbst AD, Kim SJ, Minch BA, Lindau M. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;41:736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao YF, Bhattacharya S, Chen XH, Barizuddin S, Gangopadhyay S, Gillis KD. Lab on a Chip. 2009;9:3442–3446. doi: 10.1039/b913216c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colliver TL, Hess EJ, Ewing AG. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;105:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currie KP. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9596-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madou M. Fundamentals of microfabrication. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weibel DB, Kruithof M, Potenta S, Sia SK, Lee A, Whitesides GM. Anal Chem. 2005;77:4726–4733. doi: 10.1021/ac048303p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ges IA, Dzhura IA, Baudenbacher FJ. Biomedical Microdevices. 2008;10:347–354. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenwick EM, Fajdiga PB, Howe NB, Livett BG. J Cell Biol. 1978;76:12–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.76.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenberg A, Zinder O. Cell Tissue Res. 1982;226:655–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00214792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unsicker K, Muller TH. J Neurosci Methods. 1981;4:227–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(81)90034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dzhura EV, He W, Currie KP. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1165–1174. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Todd RD, McDavid SM, Brindley RL, Jewell ML, Currie KP. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1013–1024. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825153ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atta NF, El-Kady MF, Galal A. Sensors and Actuators B. 2009;141:566–574. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atta NF, El-Kady MF, Galal A. Anal Biochem. 2010;400:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atta NF, Galal A, Ahmed RA. Journal of The Electrochemical Society. 2011;158:F52–F60. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berberian K, Kisler K, Fang Q, Lindau M. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8734–8740. doi: 10.1021/ac900674g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etienne M, Oni J, Schulte A, Hartwich G, Schuhmann W. Electrochimica Acta. 2005;50:5001–5008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan J, Du Y, Liu J, Cao W, Sun X, Zhou W, Yang X, Wang E. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5406–5412. doi: 10.1021/ac034017m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandaveer WR, Woodward DJ, Fritsch I. Electrochimica Acta. 2003;48:3341–3348. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ges IA, Ivanov BL, Schaffer DK, Lima EA, Werdich AA, Baudenbacher FJ. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2005;21:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Werdich AA, Lima EA, Ivanov B, Ges I, Anderson ME, Wikswo JP, Baudenbacher FJ. Lab Chip. 2004:4. doi: 10.1039/b315648f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ges IA, Baudenbacher F. Journal of Experimental Nanoscience. 2008;3:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ges IA, Baudenbacher F. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2010;25:1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]