SYNOPSIS

We investigated the relationship between oligomerization of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and its response to α-naphthoflavone (ANF), a prototypical heterotropic activator. Addition of ANF resulted in over a two-fold increase in the rate of CYP3A4-dependent debenzylation of 7-benzyloxy-4-(trifluoromethyl)coumarin (7-BFC) in human liver microsomes (HLM) but failed to produce activation in BD Supersomes™ or Baculosomes® containing recombinant CYP3A4 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR). However, incorporation of purified CYP3A4 into Supersomes containing only recombinant CPR reproduced the behavior observed with HLM. The activation in this system was dependent on the surface density of the enzyme. While no activation was detectable at a lipid:P450 (L/P) ratio ≥ 750, it reached 225% at an L/P ratio of 140. To explore the relationship between this effect and CYP3A4 oligomerization we probed P450-P450 interactions with a new technique based on luminescence resonance energy transfer (LRET). The amplitude of LRET in mixed oligomers of the heme protein labeled with donor and acceptor fluorophores exhibited a sigmoidal dependence on the surface density of CYP3A4 in Supersomes. Addition of ANF eliminated this sigmoidal character and increased the degree of oligomerization at low enzyme concentrations. Therefore, the mechanisms of CYP3A4 allostery with ANF involve effector-dependent modulation of P450-P450 interactions.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450 3A4, Oligomerization, α-Naphthoflavone, luminescence resonance energy transfer (LRET), protein-protein interactions, microsomes

Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), the major drug-metabolizing enzyme in human liver, is the most prominent example of a P450 that exhibits so-called “atypical kinetics”. These kinetic “abnormalities” are revealed in sigmoidal dependencies of the rate of metabolism on substrate concentration (homotropic cooperativity) or activation of metabolism of one substrate by a second one (heterotropic cooperativity). The most common interpretation of all known examples of CYP3A4 cooperativity is that the large substrate-binding pocket of microsomal drug metabolizing cytochromes P450 sometimes requires more than one substrate molecule to assure a productive binding orientation of at least one of them (see [1–3] for review). The presence of at least two molecules of some substrates in the binding pocket of CYP3A4 is well established [4–6]. The above model also provides a reasonable explanation for most cases of homotropic cooperativity but fails to explain complex instances of heterotropic activation in CYP3A4. Attempts to delineate the mechanism of additive effects of different effectors or lack of competition between two substrates each possessing homotropic cooperativity have led researchers to propose complex and mutually incompatible models involving the presence of three or even more substrate-selective binding sites in one enzyme molecule [7–11].

In our view, one of the most important obstacles to understanding P450 activation is that all observations of cooperativity, whether homotropic or heterotropic, are considered together and presumed to have similar mechanistic grounds. However, the actual experimental observations diverge into two different categories. On the one hand, there are numerous observations of cooperative effects on enzyme-substrate interactions that are reflected in S-shaped dependencies of the rate of metabolism on substrate concentration (homotropic cooperativity) or increase in enzyme affinity for one substrate in the presence of another. In this latter kind of heterotropic cooperativity, the effector increases the activity of the enzyme at low substrate concentrations but has no effect on turnover or even inhibits the enzyme at saturating substrate. Such examples are best represented by the effect of α-naphthoflavone (ANF) on hydroxylation of steroids, such as progesterone or testosterone [12–16].

On the other hand, there are numerous cases of strong effects of activators, such as ANF [17–19], steroids [9, 20], or quinidine [8, 21–24] on (Vmax or kcat) that do not necessarily involve any effect on enzyme-substrate interactions. Thus, addition of ANF to CYP3A4-containing microsomal systems was shown to cause a dramatic (12 – 45-fold) enhancement of metabolism of phenanthrene [17], phenacetin [18], or benzo[a]pyrene [19] measured under saturating concentrations. Similarly, quinidine causes a multifold increase in the rate of CYP3A4-dependent metabolism of such substrates as diclofenac, R-warfarin, piroxicam [23–24], and methoxicam [22].

From our perspective, the examples where no change in Vmax is observed are fundamentally different from the latter case of “true” heterotropic activation. The first type of cooperativity reflects simple additive effects of multiple substrate molecules bound in a large substrate binding pocket and, according to Sligar and co-authors, involves no specific allosteric effects [2, 16]. However, the observations of multi-fold increases in enzyme turnover may be better explained with a model involving effector-induced redistribution of a pool of P450 conformers with different activity and substrate specificity [1, 19]. This hypothesis is supported by the modulatory effect of allosteric activators such as ANF on the partitioning between CYP3A4 conformers revealed in the kinetics of CO-rebinding after flash photolysis [19] or dithionite-dependent reduction [25] in enzyme oligomers.

Implicit in these results are slow transitions between persistent CYP3A4 conformers, so that the distribution of the enzyme between populations remains unchanged within the time frame of the experiments. The cause of such apparent “freezing” of conformational states of the enzyme remains puzzling. From our perspective, oligomerization of cytochrome P450 in the microsomal membrane and in reconstituted systems (see [26–27] for review) is the most viable explanation for such persistent heterogeneity [1]. According to our hypothesis, the functional heterogeneity of the CYP3A4 pool is caused by diverse conformations and/or orientation of the subunits in the enzyme oligomer. Thus, the instances of “true” heterotropic activation in CYP3A4 reveal an allosteric transition associated with a change in the degree of oligomerization and/or alteration of the architecture of the oligomer.

The present study probes the above concept through investigation of the interrelationship between the activating effect of ANF and the degree of CYP3A4 oligomerization in microsomal membranes. We studied the dependence of the effect of ANF on kinetic parameters of O-debenzylation of 7-BFC by CYP3A4 on the surface density of the enzyme in model microsomal membranes. These studies were complemented with examination of the effect of CYP3A4 concentration in the membrane on the degree of its oligomerization assessed with a new LRET-based method. Our results demonstrate a strong parallelism of the degree of P450 oligomerization with its susceptibility to activation by ANF. We also demonstrate a marked effect of ANF on the equilibrium of P450 oligomerization and architecture of the enzyme oligomers. In toto, our results establish P450-P450 interactions as a central element in the mechanism of CYP3A4 allostery.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

7-Hydroxy-4-(trifluoromethyl)coumarin (HFC), glucose-6-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from baker’s yeast, protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp., protocatechuic acid, NADPH, and L-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC) from egg yolk were the products of Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). L-α-phosphatidylethanolamine from bovine liver and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (phosphatidic acid, PA) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA). 7-Benzyloxy-4-(trifluoromethyl) coumarin (BFC) and CYP3A4 Baculosomes® Plus (Catalog number P2377) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). CYP3A4 BD Supersomes™ containing human recombinant CYP3A4 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (cat. number 456207) and control BD Supersomes™ containing rat recombinant NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (cat. number 456514) were from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The preparation of human liver microsomes (HLM) Xtreme-200, which represents a pool of 200 donors of both genders was obtained from Xenotech (Lenexa, KS, USA). Erythrosine iodoacetamide was from AnaSpec (San Jose, CA, USA). Erythrosine 5′-iodoacetamide (ERIA) and 2-decanoyl-1-(O-(11-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-propionyl) amino) undecyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (BODIPY-PC) were the products of Invitrogen/Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). DY-731 maleimide (DYM) was obtained from Dyomics (MoBiTec; Göttingen, Germany). Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (octylglucoside) and 7,8-benzoflavone (α-naphthoflavone, ANF) were the products of Fluka (Switzerland) and Indofine Chemical Company (Hillsbrough, NJ, USA), respectively. All other chemicals were of ACS grade and were used without further purification.

Expression and purification of CYP3A4 and its mutants

Wild-type CYP3A4 and its cysteine-depleted mutants CYP3A4(C58,C64) [28] and CYP3A4(C468) [29] were expressed as His-tagged proteins in Escherichia coli TOPP3 cells and purified as described earlier [30].

Modification with thiol-reactive probes

Prior to modification of the cysteine-depleted mutants with thiol-reactive probes we eliminated TCEP contained in the storage buffer by two repetitive 1:10 dilution/concentration cycles with the use of a Centrisart I MWCO 100 kDA concentrator (Sartorius AG, Germany). The labeling was performed by incubation of a 15 – 20 μM solution of the protein in buffer A with SH-reactive probe added at a 1.1:1 molar ratio to the protein with constant stirring under an argon atmosphere at ambient temperature for 90 – 120 min. The process of modification was monitored by decrease in the fluorescence of the label, which is due to FRET to the heme of P450. The reaction was terminated by addition of DTT to a final concentration of 3 mM. The DTT adduct of unreacted probe was removed from the concentrated samples by incubation with Bio-Beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad Hercules, CA, USA) followed by gel filtration on Bio-Spin 6 spin columns (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with buffer A.

Preparation of proteoliposomes

Proteoliposomes were obtained by incorporation of CYP3A4 into pre-formed liposomes prepared with the octylglucoside/dialysis technique described earlier [31]. Specifically, we used a 2:1:0.6 mixture of PC, PE and PA with addition of 2 μg of BODYPY-PC per mg of lipid mixture. BODIPY-labeled phospholipid was included in the mixture for easy detection of the liposomes during their separation by gel filtration. Lipids (10 mg) were mixed as chloroform solutions, and the solvent was removed by evaporation under a stream of argon gas and subsequent drying under vacuum for 2 hours. The suspension of lipids in buffer A containing 1.54% octylglucoside was prepared using a vortex mixer and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature under argon. The mixture was then diluted with the same buffer containing no detergent to a final concentration of octylglucoside of 0.43%. The mixture was dialyzed at 4 °C under constant gentle bubbling with argon gas against three changes of 1000 ml of buffer A, each containing 5 ml of Bio-Beads SM-2. After 72 hours of dialysis (24 hours per each portion of the buffer) the mixture was concentrated on 300 kDa cut-off Diaflo membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) to a phospholipid concentration of 8–15 mM and stored at −80 °C under argon. To incorporate cytochrome P450 into pre-formed liposomes a solution of purified CYP3A4 (100–150 μM) was added to an 8 mM suspension of the liposomes in Buffer A containing 1 mM DTT to reach a desired protein-to-lipid molar ratio. The mixture was incubated overnight (~16 hours) with constant stirring under an argon atmosphere at 4 °C. Separation of unbound protein by gel-exclusion chromatography on Toyopearl HW 75F resin [32] demonstrated quantitative incorporation of the enzyme into the liposomes at RL/P≥ 70. The molar ratio of phospholipids to cytochrome P450 in the final preparation was estimated based on the determination of total phosphorus in a chloroform/methanol extract according to Bartlett [33]. The proteoliposomes were stored at −80 °C under argon atmosphere.

Incorporation of CYP3A4 into model microsomes was performed by incubation of an undiluted suspension of various commercial preparations of Baculosomes® or Supersomes™ (5–7 mg/ml protein, 2–3.5 mM phospholipid) with purified CYP3A4 in 1:2000 to 1:100 molar ratios to phospholipid for 16 hours at 4°C at continuous stirring. After incubation the suspension was diluted 8 times with 100 mM K-Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 and centrifuged at 35,000 rpm in an Optima XL-80XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA) with a SW50L rotor for 90 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in the same buffer (200 μl per 500 μl of initial microsomal suspension) and briefly sonicated (2×10 sec at 40% power) with a Biologics Model 30000 sonicator with a micro-tip (BioLogics Inc., Manassas, VI, USA). The amount of incorporated cytochrome P450 was calculated from the difference between the heme protein added to the incubation media and the enzyme found in the supernatant. The content of phospholipids was estimated as described above for proteoliposomes.

Activity measurements

The rate of BFC O-debenzylation were measured by a real-time continuous fluorometric assay. A suspension of microsomes was added to 300 μl of 0.1 M Na-HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, to a final P450 concentration of 0.02 – 0.1 μM and placed into a 5 x 5 mm quartz cell with continuous stirring and thermostated at 25 °C. An aliquot of a 20 mM stock solution of BFC in acetone was added to attain the desired concentration in the range of 1 - 100 μM. The reaction was initiated by addition of 10 μl of a cocktail of NADPH, glucose-6-phosphate, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, which resulted in final concentrations of these ingredients of 200 μM, 10 mM, and 2 units/ml respectively. The increase in the concentration of the product (HFC) was monitored with a Cary Eclipse (Varian Inc., Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or computerized Hitachi F2000 (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) spectrofluorometer equipped with a thermostated cell holder and a magnetic stirrer [34], using an emission wavelength of 500 nm and excitation at 404 nm. The rate of formation of HFC was estimated by determining the slope of the linear part of the kinetic curve recorded over a period of 3 – 6 min. Calibration of the assay was performed at the end of each day by measuring the intensity of fluorescence in a series of 4–5 samples of the same reaction mixture containing HFC at concentrations from 0.5 to 3 μM.

Phosphorescence spectroscopy measurements were performed with the use of a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer equipped with a Peltier 4-position cell holder or with a FLS920 fluorescence spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments Inc., Edinburgh, UK) equipped with Model 63501 Xenon flash lamp illuminator (Oriel Instruments, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) and custom software for acquisition of delayed phosphorescence spectra. The excitation of donor phosphorescence was performed with monochromatic light centered at 540 nm with 20 nm bandwidth (Cary Eclipse) or with a broadband light passed through a 560 nm short-pass filter (FLS920). The spectra in the 620 – 850 nm wavelength region were recorded with 18–20 nm emission bandwidth and 100 μs (Eclipse) or 175 μs (FLS920) delay time.

Interactions of DYM-labeled CYP3A4 with erythrosine-labeled protein were judged from the kinetics of increase in the amplitude of LRET assessed from a series of spectra of delayed emission taken in 4 min time intervals during co-incubation of DY-labeled proteins with membranes containing the erythrosine-labeled enzyme. The incubation was performed at 4 °C under anaerobiosis, which was achieved by addition of the oxygen-scavenging enzyme protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase (0.5 units/ml) and protecatechuic acid (20 mM). The experiments with liposomes were performed in 0.1 M Na-Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM KCl and 20% glycerol. In the case of Supersomes the incubation buffer was 0.1 M K-phosphate, pH 7.4. The total heme protein concentration in the incubation media was in the range of 2 – 5 μM.

Analysis of series of spectra obtained in fluorescence spectroscopy experiments was done by principal component analysis (PCA) [35–36]. To resolve the changes in the fluorescence of the donor and acceptor we used a least-squares fitting of the spectra of the first principal components by a combination of the standard spectra of emission of CYP3A4 labeled with ERIA and DYM. All data treatment procedures and curve fitting were performed using a 32-bit version of our SPECTRALAB software [35] running under Windows-XP™.

P450 structure and binding pocket analysis

P450 structure analysis was performed with the Internal Coordinate Mechanics (ICM) software package [37] using data collected in the Pocketome database [38]. For the analysis of P450-P450 interactions each P450 enzyme molecule in the PDB was studied in the context of its crystallographic neighbors including other P450 molecules in the asymmetric unit as well as the symmetry related molecules. Binding pocket analysis was performed using the ICM PocketFinder tool [39]. The algorithm is based on contouring of a transformed Lennard-Jones potential calculated from a three-dimensional protein structure. The method predicts the likelihood of small molecule binding in a particular location from the size and shape of the calculated envelope. Compound docking was performed with the ICM Ligand Editor tool. Fully flexible ligands were docked in the receptor binding pocket represented as a set of potential grid maps. The obtained poses were combined with the full-atom model of the binding pocket and rescored using the ICM full-atom ligand binding score.

RESULTS

Effect of ANF on O-debenzylation of 7-BFC in human liver microsomes and in model microsomes containing recombinant CYP3A4

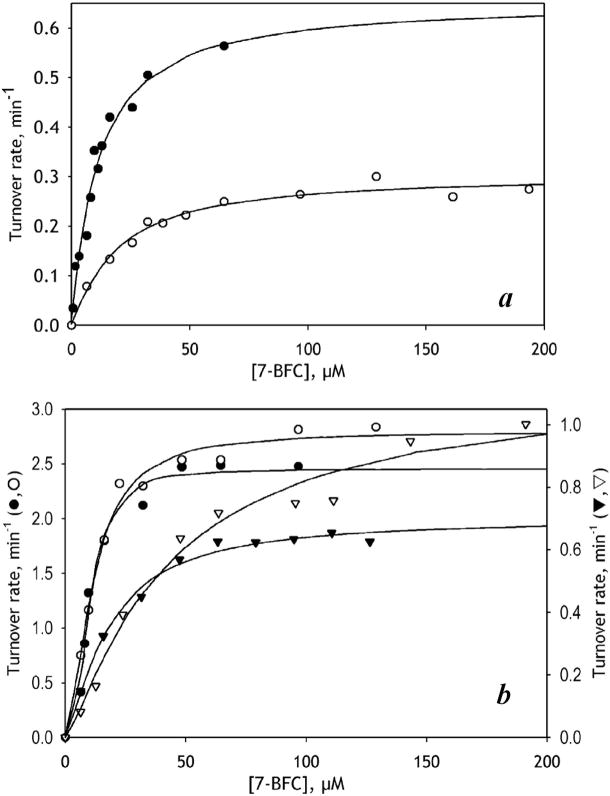

Consistent with our earlier studies in a micellar reconstituted system [14], we observed a clear effect of ANF on 7-BFC metabolism in human liver microsomes (HLM) (Fig. 1). Fitting the dependence of the reaction rate on substrate concentration in the absence of ANF with the Hill equation yielded an S50 value of 15.8 μM and a Hill coefficient (nH ) of 1.4. Addition of 25 μM ANF caused a notable decrease in S50 and eliminated cooperativity of 7-BFC metabolism (Fig 1a, Table 1). These changes were associated with an over 2-fold increase in kcat.

Figure 1.

Effect of ANF on 7-BFC O-debenzylation in human liver microsomes (a) and in CYP3A4 Baculosomes (b, circles) and CYP3A4 Supersomes (b, triangles). The titration curves obtained in the absence of effector and in the presence of 25 μM ANF are shown with open and closed symbols, respectively. Solid lines represent the approximations of the data sets with the Hill equation.

TABLE 1.

EFFECT OF ANF ON O-DEBENZYLATION OF 7-BFC IN VARIOUS MICROSOMAL SYSTEMS*

| System | PL/P450, mol/mol | P450/FP, mol/mola | ANFb | S50, μM | nh | kcat, min−1 | kcat in the presence of ANF, % of control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLM | 2880 | 4.25 | − | 15.8 ± 3.2 | 1.43 ± 0.21 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 211 ± 40 |

| + | 11.6 ± 2.3 (0.10) | 1.04 ± 0.18 (0.05) | 0.52 ± 0.08 (<0.01) | ||||

| CYP3A4-Supersomes | 3040 | 4.10 | − | 12.5 ± 3.5 | 1.59 ± 0.41 | 0.55 ± 0.22 | 76 ± 31 |

| + | 11.1 ± 3.6 (0.61) | 1.46 ± 0.30 (0.65) | 0.41 ± 0.03 (0.53) | ||||

| CYP3A4-Baculosomes | 2640 | 0.47 | − | 8.8 ± 3.0 | 2.16 ± 0.50 | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 81 ± 27 |

| + | 9.0 ± 3.0 (0.38) | 2.38 ± 0.28 (0.36) | 3.4 ± 1.8 (0.52) | ||||

| CYP3A4-Supersomes +CYP3A4c | 450 | 12.3 | − | 11.6 ± 4.9 | 1.88 ± 0.60 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 60 ± 5 |

| + | 6.9 ± 1.6 (0.11) | 1.01 ± 0.11 (0.05) | 0.33 ± 0.05 (0.75) | ||||

| CYP3A4-Baculosomes +CYP3A4c | 270 | 7.60 | − | 13.5 ± 5.7 | 1.79 ± 0.32 | 0.65 ± 0.24 | 136 ± 29 |

| + | 25.7 ± 12.8 (0.14) | 1.30 ± 0.33 (0.08) | 0.85 ± 0.17 (0.26) |

Ratio of molar content of (total) cytochrome P450 to the content of CPR estimated from the rate of NADPH-dependent reduction of cytochrome c.

“+” and “−” signs designate the values obtained in the presence and absence of 25 μM ANF, respectively.

Preparation of CYP3A4 Baculosomes enriched with CYP3A4 by co-incorporation of the purified enzyme (see Materials and Methods).

The values given in the Table were obtained by averaging the results of 2–4 individual measurements and the “±” values show the confidence interval calculated for p = 0.05. The values in parentheses given in the columns for S50, nh and kcat represent the p-values of Student’s t-test for the hypothesis of equality of the respective values measured in the presence of ANF with those observed without ANF. The p-values ≤0.05 are underlined to emphasize the effects with high statistical significance.

We also studied the effect of ANF on 7-BFC metabolism in two commercial preparations of insect cell microsomes (ICM) containing recombinant human CYP3A4 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, (CPR), namely BD Supersomes™ and CYP3A4 Baculosomes® Plus. In contrast to the increase in kcat in HLM, some inhibition by ANF was observed in both Baculosomes and Supersomes (Table 1). Furthermore, in contrast to HLM, in model microsomes ANF elicited no effect on either the Hill coefficient or S50.

In order to probe whether this difference between HLM and the model microsomes is related to differences in P450-P450 interactions and the degree of CYP3A4 oligomerization in particular, we studied the effect of incorporation of additional amounts of purified CYP3A4 into the CYP3A4-containing Baculosomes or Supersomes. As seen from Table 1 and Fig. 1b, addition of ANF to CYP3A4-enriched Supersomes (but not Baculosomes) eliminated cooperativity with 7-BFC and decreased S50, similar to what is observed in HLM. However, neither of the two CYP3A4-enriched preparations revealed any statistically significant increase in kcat in the presence of ANF (Table 1).

Effect of ANF on O-debenzylation of 7-BFC in model microsomes with incorporated purified CYP3A4

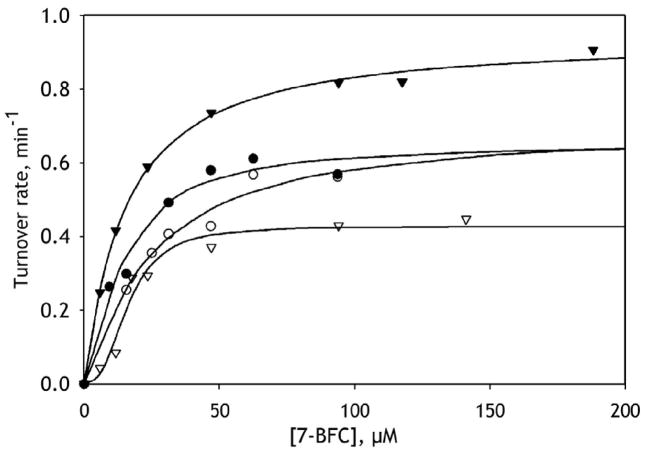

In order to develop a model system that better reproduces the allosteric properties of CYP3A4 observed in HLM we incorporated purified CYP3A4 into commercially available “control” Supersomes containing recombinant CPR but no P450 (BD Biosciences, cat. #456514). This approach allowed us to obtain model membranes with an RL/P varying from 140 to 2700. As seen from Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, the membranes with high surface density of CYP3A4 (RL/P <500) closely reproduced the behavior observed with HLM. Specifically, the addition of ANF eliminated the homotropic cooperativity of 7-BFC debenzylation and caused up to a 220% increase in kcat. Interestingly, the dependencies of nH and kcat on the CYP3A4 surface density are represented with S-shaped curves having an inflection point at RL/P ~700. The dependence of the activation by ANF on the surface density of CYP3A4 in the membrane supports our initial concept that the heterotropic cooperativity involves modulation of the quaternary structure of the oligomer and/or the degree of oligomerization.

Figure 2.

Effect of ANF on 7-BFC O-debenzylation in CPR-containing Supersomes with purified CYP3A4 incorporated into the microsomal membrane at an L/P ratio of 1350 (circles) and 175 (triangles). The titration curves obtained in the absence of effector and in the presence of 25 μM ANF are shown with open and closed symbols, respectively. Solid lines represent the approximations of the data sets with the Hill equation.

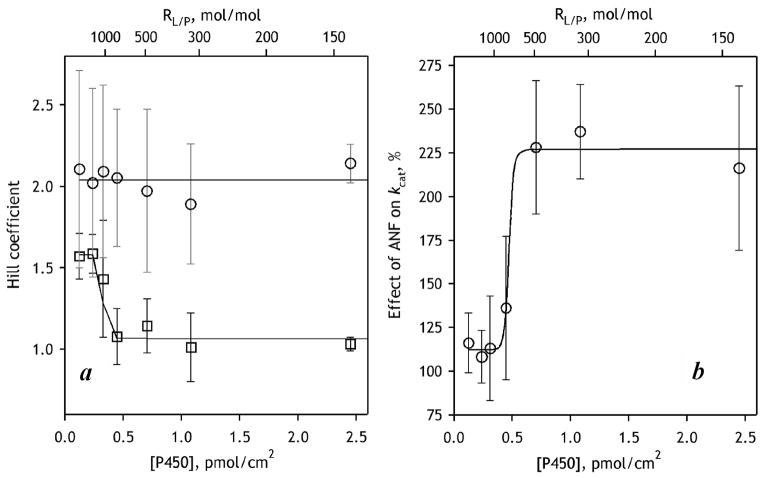

Figure 3.

Dependence of the effect of ANF on 7-BFC metabolism in CPR-containing Supersomes with incorporated CYP3A4 on the surface density of CYP3A4 in the membrane. Panel (a) shows the effect of surface density of CYP3A4 on the Hill coefficient of 7-BFC metabolism in the absence of effector (circles, grey error bars) and in the presence of 25 mM ANF (squares, black error bars). Panel (b) illustrates the effect of the P450 concentration in the membrane on the activation by 25 μM ANF as assessed by kcat. Error bars represent the standard deviation calculated on the basis of 2–3 measurements.

Design of a method for detection of P450-P450 interactions

We next sought to develop a direct approach for studying the degree of CYP3A4 oligomerization in the membranes and the effect of allosteric effectors on P450-P450 interactions. For this purpose we employed resonance energy transfer between donor and acceptor probes incorporated into two separate preparations of the enzyme. According to our design the formation of mixed oligomers of the labeled enzyme molecules would result in resonance energy transfer with an amplitude proportional to the degree of oligomerization.

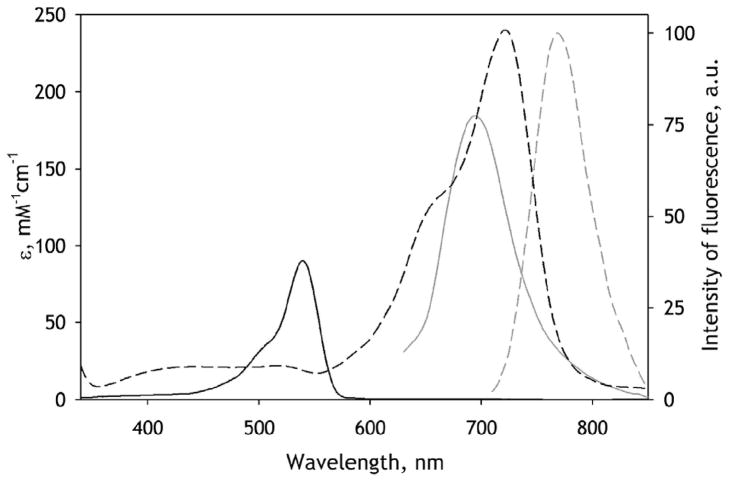

Selection of a donor/acceptor pair applicable in studies of heme proteins is challenging due to overlap of the heme absorbance with the emission bands of most commonly used fluorescent probes. In addition, the steady-state measurements of FRET are often obscured by the usual overlap of the excitation band of the donor with that of the acceptor. An attractive alternative to FRET is luminescence energy transfer (LRET), which uses the long-lived triplet state of a phosphorescent probe as an energy donor. Registration of the delayed fluorescence ensures a thorough selectivity in monitoring of the emission that originates from energy transfer. In our design we employed erythrosine iodoacetamide (ERIA) as an SH-reactive phosphorescent probe. The phosphorescence of this dye is centered at 695 nm and has a life time of 0.1–0.2 ms. An appropriate acceptor dye, DY-731 maleimide (DYM), was found among recently introduced near-infrared fluorescent tandem dyes [40]. The spectral properties of this new donor/acceptor pair are illustrated in Fig. 4. The R0 distance for this pair calculated assuming random rotation of at least one of the fluorophores (κ2 =2/3) is equal to 33.6 Å, which is long enough to ensure efficient LRET between the dyes attached to neighboring subunits in the enzyme oligomer.

Figure 4.

Spectral properties of erythrosine (black lines) and DY-731 (gray lines). Solid lines show the spectra of extinction. Dashed lines show the spectra of fluorescence normalized to area.

In order to ensure site-directed incorporation of the probes we used cysteine-depleted mutants bearing only two CYP3A4(C58,C64) or one CYP3A4(C468) potentially reactive cysteines [28–29]. As shown in our earlier study [28], Cys-58 has very poor accessibility for modification with large thiol-reactive probes. Therefore the stoichiometric labeling of CYP3A4(C58,C64) with ERIA is presumed to result from site-specific incorporation of the probe at Cys-64, whereas CYP3A4(C468) can only be labeled at Cys-468.

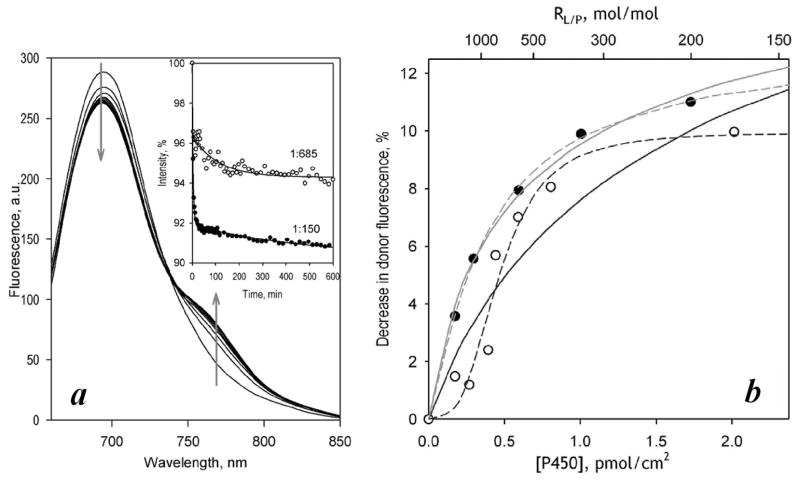

Studies of CYP3A4 oligomerization in proteoliposomes

To probe the applicability of the LRET donor/acceptor pair for monitoring P450-P450 interactions we began with studies of CYP3A4 oligomerization in proteoliposomes. We used either CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA or CYP3A4(C468)-ERIA as LRET donors, whereas CYP3A4(C468)-DYM was used as the LRET acceptor. We prepared large uni-lamellar liposomes containing either one of the above mentioned erythrosine-labeled preparations of the enzyme at RL/P varying from 150 to 3000 (see Materials and Methods). Incubation of these preparations with equimolar amounts of CYP3A4(C468)-DYM was expected to result in co-incorporation of this protein into the membrane and formation of mixed oligomers of donor- and acceptor-labeled proteins.

As seen from Fig. 5a, this incubation resulted in a profound decrease in the donor emission accompanied by appearance of the delayed fluorescence of the acceptor. Kinetic curves of the time-dependent decrease in the intensity of donor fluorescence observed at two different RL/P values (Fig. 5a inset) show clearly that the amplitude of LRET decreased with decreasing surface density of CYP3A4. These observations are consistent with time-dependent formation of mixed oligomers of the two proteins signified by the appearance of LRET. The amplitude of LRET established at the end of the kinetics of subunit exchange is therefore proportional to the steady-state concentration of the mixed oligomers in the membrane.

Figure 5.

Interactions of ERIA- and DYM-labeled cysteine-depleted mutants in proteoliposomes studied with LRET. Panel a shows a series of spectra of delayed emission recorded during incubation of a 5 μM suspension of CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA incorporated into proteoliposomes at RL/P=150 with 5 μM CYP3A4(C468)-DYM. (The RL/P after incorporation of CYP3A4(C468)-DYM is equal to 75). The inset shows the time dependencies of normalized intensity of donor fluorescence obtained in the experiments at an RL/P of 75 and 1350. Solid lines represent the approximation of the kinetic curves with a bi-exponential equation. Panel b illustrates the dependence of the LRET amplitude on the CYP3A4 concentration in the membrane for the interactions of CYP3A4(C468)-ERIA (triangles, dashed line) and CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA (circles, solid lines) with CYP3A4(C468)-DYM. Results of the experiment with CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA carried out in the absence and the presence of 50 μM ANF are shown with open circles, black line, and closed circles, gray line, respectively. The lines show the results of the fitting of the data sets to equation (1).

As seen from Fig. 5a, completion of the processes of protein incorporation and subunit exchange took about 12–16 hours. The kinetic curves of decrease in donor fluorescence may be approximated with a bi-exponential equation (Fig. 5a inset). The offset value (intensity of fluorescence extrapolated to infinite time) determined from these approximations was used to estimate the amplitude of LRET at equilibrium. Similar results were also obtained with the use of CYP3A4(C468)-ERIA as the LRET donor.

The dependencies of LRET amplitude on the CYP3A4 concentration in the membrane obtained with CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA/CYP3A4(C468)-DYM and CYP3A4(C468)-ERIA/ CYP3A4(C468)-DYM donor/acceptor pairs are shown in Fig, 5b. The X-axis of this plot represents the surface density of P450 in the membrane calculated based on RL/P, assuming the average area of the membrane per one phospholipid molecule to be of 0.72 nm2 [41] and the footprint of membrane-bound CYP3A4 to be equal to 16 nm2.

Theoretically, these dependencies may be used to estimate apparent dissociation constants of CYP3A4 oligomers. However, the theory of diffusion-influenced association in two-dimensional space is complex and poorly developed [42–43]. In the absence of an appropriate formalism, we approximated these dependencies with an equation for the equilibrium of dimerization in solution:

| (1) |

where [E]0, [EE], and KD are the total concentration of the associating compound (enzyme), the concentration of its dimers, and the dissociation constant, respectively. Despite the provisional nature of these approximations, they resulted in reasonable fits (ρ2 ≥ 0.9) that did reveal any systematic deviations from the experimental results. The parameters resulting from this fitting may be used for a rough estimation of the oligomerization state of CYP3A4 in the membrane and LRET efficiency in the oligomers. According to our analysis (Table 2), the lipid-to-protein ratio at which the enzyme is 50% oligomerized (R50) is around 700 for the CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA/CYP3A4(C468)-DYM pair and approaches 900 for the CYP3A4(C468)-ERIA/CYP3A4(C468)-DYM pair. Relocation of the donor fluorophore from Cys-64 to Cys-468 caused no considerable changes in either the LRET efficiency or apparent Kd of the enzyme oligomers. Both pairs of proteins exhibited a LRET efficiency of ~25% (Table 2), so that the interprobe distance in the mixed oligomers may be estimated to be in the range of 40–42 Å.

TABLE 2.

OLIGOMERIZATION OF CYP3A4 IN MODEL MEMBRANES STUDIED BY LRET

| System | A(1:150),%a | Amax, % | KD, pmol/cm2 | (RL/P)diss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Liposomes, CYP3A4(C468)ERIA+CYP3A4(C468)DYM | 15.3 | 25.5 ±0.5 | 0.49 ±0.09 | 897 |

| Liposomes, CYP3A4(C58,C64)ERIA+CYP3A4(C468)DYM | 14.8 | 24.3 ±3.5 | 0.59 ±0.16 | 736 |

| Same +ANF | 16.5 | 29.1 ±2.7 | 0.71 ±0.15 | 908 |

| Supersomes CYP3A4(C58,C64)ERIA+CYP3A4(C468)DYM | 10.0 | 23.8 ±4.7 | 1.65 ±0.49 | 210 |

| Same +ANF | 11.6 | 19.8 ±0.7 | 0.64 ±0.06 | 541 |

The “±” values show the confidence interval calculated for p = 0.05.

Amplitude of LRET-dependent decrease in the intensity of donor fluorescence observed at L/P ratio of 1:150.

L/P ratio at which the amplitude of the titration curves reaches 50% of maximal.

We also probed the effect of ANF on P450-P450 interactions detected by LRET. The dependence of LRET amplitude on surface density of CYP3A4 obtained with the CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA/CYP3A4(C468)-DYM pair in the presence of ANF is shown in Fig. 5b with closed circles and a grey line. As seen from this plot and Table 2, addition of ANF had no effect on the parameters of P450-P450 interactions in this system.

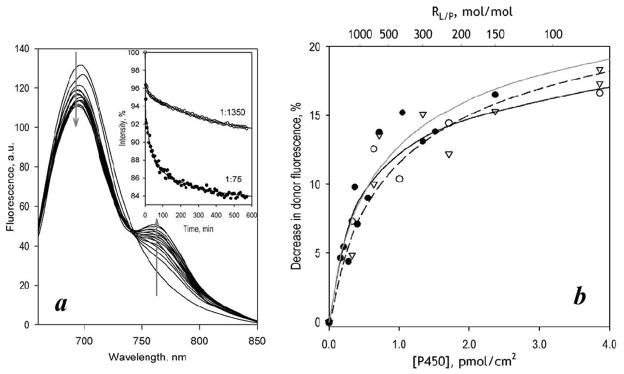

Studies of P450-P450 interactions in model microsomes

This method of detecting P450 oligomerization was then applied to study CYP3A4 in the absence and presence of ANF in membranes of Supersomes with incorporated CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA and CYP3A4(C468)-DYM proteins. The setup of the experiments was similar to that used with liposomes. It should be noted, however, that in this case we were forced to change the incubation buffer used for CYP3A4 incorporation. Our initial attempts to use 0.1 M Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, as with liposomes, did not result in any detectable incorporation of the proteins into the membrane. However, replacement of the incubation buffer with 0.1 M K-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, allowed us to obtain microsomes containing both CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA and CYP3A4(C468)-DYM.

As shown in Fig. 6a, incubation of CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA-containing Supersomes with CYP3A4(C468)-DYM resulted in appearance of LRET. Similar to liposomes, increase in the surface density of P450 augmented the LRET amplitude, which tended to approach a limit at high P450 concentrations (Fig. 6b, open circles)1. Approximation of this data set with equation (1) suggests that the microsomal membrane is characterized by a considerably higher Kd value of CYP3A4 oligomers than the proteoliposomal system (Table 2). However, unlike nearly hyperbolic dependencies observed with liposomes, the plot of LRET amplitude on P450 concentration in Supersomes was distinctly S-shaped (Fig. 6b, open circles), so that the fitting of this dataset to equation (1) was poor and revealed large systematic deviations (Fig. 6b, black solid line). Approximation of this dataset with the Hill equation (nH = 3.1 ± 1.5) resulted in a considerably better fit (Fig. 6b, black dashed line). The LRET efficiency of ~10% estimated with this arbitrary approximation corresponds to an interprobe distance of ~48 Å.

Figure 6.

Interactions of CYP3A4(C58,C64)-ERIA and CYP3A4(C468)-DYM mutants in CPR-containing Supersomes studied with LRET. Panel a shows a series of spectra of delayed emission recorded during incubation of a 3 μM suspension of CYP3A4(C64,C468)-ERIA incorporated into Supersomes at RL/P=300 with 3 μM CYP3A4(C468)-DYM. (The RL/P ratio after incorporation of CYP3A4(C468)-DYM is equal to 150). The inset shows the time dependencies of normalized intensity of donor fluorescence obtained in the experiments at the RL/P of 150 and 685. Solid lines represent the approximation of the kinetic curves with a bi-exponential equation. Panel b illustrates the dependence of the LRET amplitude on CYP3A4 concentration in the membrane. Solid lines show the results of the fitting of the data sets to the equation (1). Dashed lines show the approximations of the data with the Hill equation. Open circles and black lines show the results obtained in the absence of effector. Data obtained in the in the presence of 50 μM ANF are shown with filled circles and gray lines.

In contrast to our observations with proteoliposomes, where the effect of ANF on P450-P450 interactions (Fig. 5) was insignificant, addition of ANF to Supersomes caused a prominent change in the shape of the dependence of the degree of oligomerization on P450 concentration in the membrane (Fig. 6b). Interactions of CYP3A4 with ANF eliminated the sigmoidal character of this dependence. Fitting of the data set obtained in the presence of ANF with Eq. 1 (Fig. 6b, black solid line) resulted in an adequate approximation and did not reveal the large systematic deviations seen in the absence of ANF. According to our results, addition of ANF to our model microsomal system promotes oligomerization of the enzyme, which is reflected in a decreased Kd and increased S50 (Table 2). Strong parallels between the effect of ANF on P450-P450 interactions (Fig. 6) and the dependence of the activating effect of ANF on surface density of CYP3A4 in Supersomes (Fig. 3) suggest that the ANF-dependent modulation of P450-P450 interactions is directly related to the mechanism of enzyme allostery.

DISCUSSION

The central hypothesis of our study was that heterotropic cooperativity of CYP3A4 that results in an increased kcat reflects effector-induced changes in enzyme oligomerization. The basic premise of our experimental design was that the involvement of protein-protein interactions in CYP3A4 allostery should reveal itself in a dependence of cooperativity on enzyme concentration (surface density) in the membrane. Rigorous test of the hypothesis required two methodological advances: 1) a catalytically active membranous system in which the lipid:protein ratio could be varied systematically, and 2) a reliable method for monitoring CYP3A4 oligomerization. Studies with a model system in which purified CYP3A4 was incorporated into commercially available “control” Supersomes containing recombinant CPR but no P450 provided decisive support for the effect of CYP3A4 concentration in the membrane on the allosteric properties of the enzyme. Specifically, model membranes with high surface density of CYP3A4 (RL/P <700) closely reproduce the behavior of HLM, as evidenced by loss of homotropic cooperativity of 7-BFC debenzylation and an over two-fold increase in turnover in the presence of ANF.

Furthermore, the LRET method we developed to link the surface density of CYP3A4 in the membrane to the oligomerization state provided a powerful complement to the activity studies. Strong parallels between the degree of CYP3A4 oligomerization in the membrane and the extent of activation by ANF suggest that the effector-dependent modulation of P450-P450 interactions is directly related to the mechanism of allostery. A remarkable finding is the sigmoidal character of the dependencies of the degree of CYP3A4 oligomerization (Fig. 6) and the effect of ANF on enzyme turnover (Fig. 3) on the surface density of CYP3A4 in Supersomes. Addition of ANF eliminates the sigmoidal character of dependence of LRET amplitude on CYP3A4 concentration and causes a multifold increase in the degree of CYP3A4 oligomerization at low enzyme concentrations. This observation reveals ANF as a potent modulator of P450-P450 interactions.

In the process of refining our model system, we discovered an intriguing difference between HLM and insect cell microsomes (ICM) containing recombinant CYP3A4 and CPR. Specifically, the increase in the rate of 7-BFC metabolism caused by addition of ANF to HLM was not observed with either of the two brands of CYP3A4-containing ICM, namely BD Supersomes™ or Baculosomes®. In Supersomes, the levels of CYP3A4 are 4–5 times higher than that of CPR (similar to HLM), whereas in Baculosomes CPR is present in 2–3 fold molar excess over the heme protein. This finding suggests that the contrast between HLM and the recombinant systems is not related to the differences in CYP3A4:CPR ratio and ensuing degree of CYP3A4 saturation with the reductase. Rather, a likely explanation for the difference between HLM and the model microsomes is the high content of P450 apo-protein (heme-free enzyme) in the ICM [45–47]. Interactions between holo- and apo- CYP3A4 may have an important effect, as noted previously [48].

In addition, the S-shaped dependence of the oligomerization equilibrium on protein concentration was not observed with proteoliposomes (Fig. 5). This contrast may indicate that the oligomerization of CYP3A4 in microsomal membranes is affected by its interactions with other proteins, CPR in particular. In support of this inference, a decrease in the degree of oligomerization of cytochrome P450 1A2 caused by incorporation of CPR into the membrane of proteoliposomes was demonstrated in studies of rotational diffusion of the heme protein [49]. It may be hypothesized that the oligomerization of CYP3A4 at low protein concentration and low P450:CPR ratios is hindered by the enzyme interactions with the reductase. This factor becomes less important at high concentration of the hemeprotein, when the concentration of CPR in the membrane becomes insufficient to prevent oligomerization.

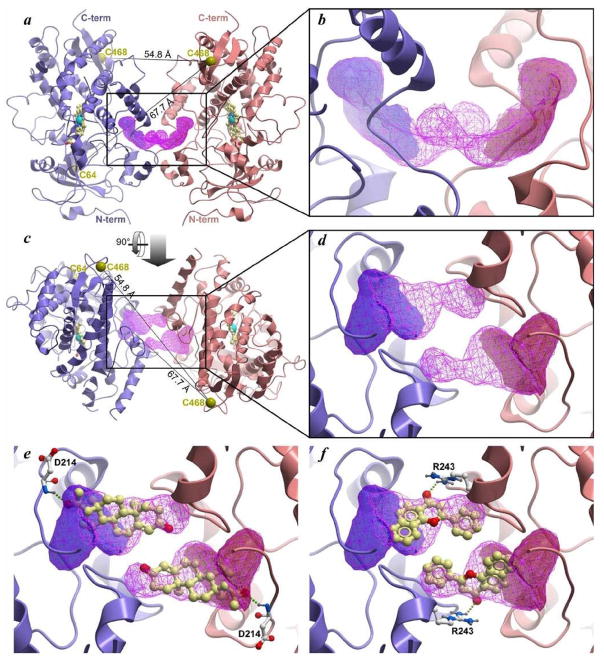

A structural explanation for the relationship between CYP3A4 allostery and its oligomerization may be based on the observations of peripheral ligand binding site at the interface of the crystallographic dimer of some microsomal drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450. Thus, binding of two molecules of palmitic acid was observed in a hollow formed in the vicinity of the F′ and G′ helices of two interacting molecules of CYP2C8 (PDB 1PQ2 [50]). Similar interactions with two molecules of peripherally-bound progesterone were also detected in the crystallographic dimer of CYP3A4 (PDB 1W0F [51]). Our recent studies of the interactions of Fluorol 7GA with CYP3A4 by FRET also suggested that the same region is the most probable site for high affinity peripheral binding [29]. The role of peripheral substrate binding at this site in the mechanisms of CYP3A4 allostery was hypothesized by Williams and co-workers [51] and was advocated in our studies [28–29], as well as in the publications from the laboratories of Atkins [52] and Sligar [3, 53].

Detailed analysis of peripheral ligand binding in the crystallographic dimers of CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 [50–51] indicates that the high-affinity interactions at this site require oliogomeric protein. Many structures of CYP3A4 feature a dimer of subunits interacting through their F′ and G′ helices. The dimer is observed either as a part of an asymmetric unit (ASU) in the crystal structure (e.g. PDB 2VOM and 2JOD [54]), or between the monomer in the ASU with a crystallographic symmetry neighbor (e.g. PDB 1TQN [50]). Moreover, the dimer geometry is compatible with the proposed membrane orientation of the enzyme and is consistent across multiple structures of CYP3A4 and found in structures of other P450 enzymes: 1A2, 21A, 2A6, and 2C8. CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 dimer structures are unique in that the dimer interface forms a cavity that can accommodate small molecule ligands. However, ligands are unlikely to bind with high affinity in the corresponding pockets in the monomeric subunits due to their small size and low degree of “buriedness”. In other words, the peripheral site in the 3A4 structures appears to represent a ligand-binding cavity formed by the surfaces of two interacting molecules of the enzyme. Dissociation of the enzyme dimer will eliminate this cavity and thus compromise ligand binding.

Location of this peripheral site in the dimer of CYP3A4 (PDB 1W0F) is illustrated in Fig. 7. In this figure we also show one of the best poses of two ANF molecules docked into this site. It should be noted that this hypothetical CYP3A4 dimer structure is consistent with LRET efficiencies observed in our experiments. These efficiencies suggest that the inter-probe distances for C468-ERIA/C468-DYM and C468-ERIA/C64-DYM pairs are in the range of 40–48 Å. Given the large sizes of ERIA and DYM probes (10–12 and 15–20 Å respectively), these estimates are in reasonable agreement with the distances between the sulfur atoms in Cys468/Cys468 and Cys468/Cys64 pairs in the CYP3A4 dimer (54.8 and 67.7 Å respectively).

Figure 7.

CP3A4 dimer geometry observed in the structure of the CYP3A4 complex with progesterone (PDB 1W0F) and several other X-ray structures of the enzyme. (a) view from the side along the membrane plane; (b) zoom in on the binding site at the dimer interface; (c) view perpendicular to the membrane plane; (d) zoom in on the binding site at the dimer interface. The ligand binding envelopes identified by ICM PocketFinder in the monomeric structures are shown as solid red and blue envelopes; sites identified in the dimeric complex are represented by magenta wire mesh. C468/C468 and C468/C64 distances are shown in panels (a) and (c). (d) Progesterone binding to the site at the CYP3A4 dimer interface as observed by X-ray crystallography (PDB 1W0F). (e) Potential binding mode of ANF at the CYP3A4 dimer interface predicted by molecular docking to the site.

The interactions of ligands with a binding site of this kind are likely to affect the architecture of the oligomers and/or the equilibrium of oligomerization. We hypothesize therefore that the P450-P450 interface in CYP3A4 oligomers in the membrane is similar to that observed in the crystallographic dimers [51], and the peripheral progesterone binding in the vicinity of the F′ and G′ helices of two interacting CYP3A4 molecules observed in the X-ray structure is physiologically relevant. This site may have an important functional role in allosteric regulation of the enzyme by some yet unknown physiological ligand (e.g., a steroid or its derivative). The interactions of this site with some specific ligands, such as progesterone, testosterone, ANF or quinidine, may cause a change in the activity and substrate specificity of the enzyme via a ligand-induced reorganization of the enzyme oligomer.

According to this hypothesis, the divergence of the instances of heterotropic cooperativity in CYP3A4 into two categories (with and without effector-induced increases in kcat) discussed in the Introduction to this article may be caused by differences in the affinity of different substrates for a peripheral binding site. Such substrates as testosterone and progesterone, for which there is no increase in kcat in the presence of effectors, may be hypothesized to have high affinity for the peripheral site. Therefore, these substrates may serve as allosteric activators by themselves and do not require other effectors for efficient metabolism. In this case the heterotropic activation that is observed at sub-saturating substrate concentrations only may be explained by the binding of multiple molecules of both substrate and the effector in the active site of the enzyme, as analyzed by Denisov and Sligar [3]. In contrast, substrates exhibiting a considerable increase in kcat in the presence of activators (such as phenanthrene, benzo[a]pyrene, or 7-BFC) are presumably unable to interact with the peripheral site and therefore require an additional effector for enhanced metabolism. An important corollary to this hypothesis is that the increases in kcat with the latter group of substrates will only be observed in the enzyme oligomers formed in the membranes or in micellar reconstituted systems but will not be reproducible in monomeric systems such as Nanodisks.

A plausible scenario for allosteric interactions involving a conformational transition in the enzyme oligomer in response to a peripheral binding of an allosteric activator has been discussed in our earlier publication (see Fig. 2 and relevant discussion in [1]). The hypothetical mechanism of heterotropic activation of CYP3A4 introduced there is in a good agreement with the results of the present study. According to this hypothesis, the instances of heterotropic activation of CYP3A4 reveal a complex allosteric mechanism that involves effector-induced modulation of protein-protein interactions in the enzyme oligomers. An additional complexity to the allosteric properties of the ensemble of cytochromes P450 co-existing in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum is possible formation of mixed oligomers between different P450 species (see [26–27] for a review), which may disrupt the hypothetical peripheral binding site or modify its functional properties. Therefore, the allosteric properties of each individual cytochrome P450 may be modified considerably by changes in the composition of the P450 pool during cell differentiation, aging, or disease.

Our present results emphasize the functional importance of P450-P450 interactions in the microsomal membrane. Detailed exploration of these interactions and elucidation of the mechanisms of their modulation by allosteric ligands represent an ultimate requirement for delineating the key factors that dictate the catalytic properties of the ensemble of drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450 in human liver. New experimental approaches for the studies of P450-P450 interactions and their functional consequences introduced in this study, and the use of model microsomes with variable surface density of the heme protein in particular, provide a solid methodological foundation for further progress.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (grants GM054995 and GM071872).

Abbreviations used

- CYP3A4

cytochrome P450 3A4

- CPR

NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreducatse

- Hepes

N-[2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]

- BFC

7-benzyloxy-4-(trifluoromethyl)coumarin

- HFC

7-hydroxy-4-(trifluoromethyl)coumarin

- ANF

7,8-benzoquinone (α-naphthoflavone)

Footnotes

To calculate the surface density of P450 in microsomal membrane we used the value 0.95 nm2 as an estimate of the surface of the microsomal membrane corresponding to one molecule of phospholipid in a monolayer [44].

Author contributions.

D.R.D. designed the study. N.Y.D. and D.R.D. performed most of the experimental work with the help of E.V.S., who participated in LRET experiments and activity assays. IK analyzed the structures of crystallographic dimers of cytochromes P450 and built a model of peripheral interactions of ANF with CYP3A4 dimer. D.R.D. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. J.R.H contributed to the project development, data interpretation, and writing.

References

- 1.Davydov DR, Halpert JR. Allosteric P450 mechanisms: multiple binding sites, multiple conformers or both? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:1523–1535. doi: 10.1517/17425250802500028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denisov IG, Frank DJ, Sligar SG. Cooperative properties of cytochromes P450. Pharm Ther. 2009;124:151–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denisov IG, Sligar SG. A novel type of allosteric regulation: Functional cooperativity in monomeric proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernando H, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Resolution of multiple substrate binding sites in cytochrome P450 3A4: The stoichiometry of the enzyme-substrate complexes probed by FRET and Job’s titration. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4199–4209. doi: 10.1021/bi052491b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts AG, Campbell AP, Atkins WM. The thermodynamic landscape of testosterone binding to cytochrome P450 3A4: ligand binding and spin state equilibria. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1353–1366. doi: 10.1021/bi0481390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denisov IG, Baas BJ, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4 - Linkages in substrate binding, spin state, uncoupling, and product formation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7066–7076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houston JB, Galetin A. Modelling atypical CYP3A4 kinetics: principles and pragmatism. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galetin A, Clarke SE, Houston JB. Quinidine and haloperidol as modifiers of CYP3A4 activity: Multisite kinetic model approach. Drug Metab Disp. 2002;30:1512–1522. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.12.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egnell AC, Houston JB, Boyer CS. Predictive models of CYP3A4 heteroactivation: In vitro-in vivo scaling and pharmacophore modeling. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2005;312:926–937. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenworthy KE, Clarke SE, Andrews J, Houston JB. Multisite kinetic models for CYP3A4: simultaneous activation and inhibition of diazepam and testosterone metabolism. Drug Metab Disp. 2001;29:1644–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenworthy KE, Bloomer JC, Clarke SE, Houston JB. CYP3A4 drug interactions: correlation of 10 in vitro probe substrates. Brit J Clin Pharm. 1999;48:716–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CA, Kadwell SH, Kost TA, Serabjitsingh CJ. CYP3A4 expressed by insect cells infected with a recombinant baculovirus containing both CYP3A4 and human NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase is catalytically similar to human liver microsomal CYP3A4. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;319:157–167. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domanski TL, He YA, Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Dual role of human cytochrome P450 3A4 residue Phe-304 in substrate specificity and cooperativity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domanski TL, He YA, Khan KK, Roussel F, Wang Q, Halpert JR. Phenylalanine and tryptophan scanning mutagenesis of CYP3A4 substrate recognition site residues and effect on substrate oxidation and cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10150–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi010758a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borek-Dohalska L, Stiborova M. Cytochrome P450 3A activities and their modulation by alpha-naphthoflavone in vitro are dictated by the efficiencies of model experimental systems. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 2010;75:201–220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank DJ, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Analysis of heterotropic cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4 using alpha-naphthoflavone and testosterone. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5540–5545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.182055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sai Y, Dai R, Yang TJ, Krausz KW, Gonzalez FJ, Gelboin HV, Shou M. Assessment of specificity of eight chemical inhibitors using cDNA-expressed cytochromes P450. Xenobiotica. 2000;30:327–343. doi: 10.1080/004982500237541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima M, Kobayashi K, Oshima K, Shimada N, Tokudome S, Chiba K, Yokoi T. Activation of phenacetin O-deethylase activity by alpha-naphthoflavone in human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:885–898. doi: 10.1080/004982599238137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koley AP, Buters JTM, Robinson RC, Markowitz A, Friedman FK. Differential mechanisms of cytochrome P450 inhibition and activation by alpha-naphthoflavone. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3149–3152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura H, Nakasa H, Ishii I, Ariyoshi N, Igarashi T, Ohmori S, Kitada M. Effects of endogenous steroids on CYP3A4-mediated drug metabolism by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Disp. 2002;30:534–540. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngui JS, Tang W, Stearns RA, Shou MG, Miller RR, Zhang Y, Lin JH, Baillie T. Cytochrome P450 3A4-mediated interaction of diclofenac and quinidine. Drug Metab Disp. 2000;28:1043–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig E, Schmid J, Beschke K, Ebner T. Activation of human cytochrome P-450 3A4-catalyzed meloxicam 5′-methylhydroxylation by quinidine and hydroquinidine in vitro. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1999;290:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngui JS, Chen Q, Shou MG, Wang RW, Stearns RA, Baillie TA, Tang W. In vitro stimulation of warfarin metabolism by quinidine: Increases in the formation of 4′- and 10-hydroxywarfarin. Drug Metab Disp. 2001;29:877–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Li Y, Shou M, Zhang Y, Ngui JS, Stearns RA, Evans DC, Baillie TA, Tang W. Influence of different recombinant systems on the cooperativity exhibited by cytochrome P4503A4. Xenobiotica. 2004;34:473–486. doi: 10.1080/00498250410001691271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davydov DR, Fernando H, Baas BJ, Sligar SG, Halpert JR. Kinetics of dithionite-dependent reduction of cytochrome P450 3A4: Heterogeneity of the enzyme caused by its oligomerization. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13902–13913. doi: 10.1021/bi0509346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed JR, Backes WL. Formation of P450. P450 complexes and their effect on P450 function. Pharm Ther. 2012;133:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davydov DR. Microsomal monooxygenase as a multienzyme system: the role of P450-P450 interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:543–558. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.562194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsalkova TN, Davydova NY, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Mechanism of interactions of alpha-naphthoflavone with cytochrome P450 3A4 explored with an engineered enzyme bearing a fluorescent probe. Biochemistry. 2007;46:106–119. doi: 10.1021/bi061944p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davydov DR, Rumfeldt JAO, Sineva EV, Fernando H, Davydova NY, Halpert JR. Peripheral Ligand-binding Site in Cytochrome P450 3A4 Located with Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6797–6809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davydov DR, Baas BJ, Sligar SG, Halpert JR. Allosteric mechanisms in cytochrome P450 3A4 studied by high-pressure spectroscopy: pivotal role of substrate-induced changes in the accessibility and degree of hydration of the heme pocket. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7852–7864. doi: 10.1021/bi602400y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davydov DR, Sineva EV, Sistla S, Davydova NY, Frank DJ, Sligar SG, Halpert JR. Electron transfer in the complex of membrane-bound human cytochrome P450 3A4 with the flavin domain of P450BM-3: the effect of oligomerization of the heme protein and intermittent modulation of the spin equilibrium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernando H, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Kinetics of electron transfer in the complex of cytochrome P450 3A4 with the flavin domain of cytochrome P450BM-3 as evidence of functional heterogeneity of the heme protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;471:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartlett GR. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davydov DR, Kumar S, Halpert JR. Allosteric mechanisms in P450eryF probed with 1-pyrenebutanol, a novel fluorescent substrate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:806–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00565-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davydov DR, Deprez E, Hui Bon Hoa G, Knyushko TV, Kuznetsova GP, Koen YM, Archakov AI. High-pressure-induced transitions in microsomal cytochrome P450 2B4 in solution - evidence for conformational inhomogeneity in the oligomers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;320:330–344. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davydov DR, Femando H, Halpert JR. Variable path length and counter-flow continuous variation methods for the study of the formation of high-affinity complexes by absorbance spectroscopy. An application to the studies of substrate binding in cytochrome P450. Biophys Chem. 2006;123:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abagyan R, Totrov M. Biased probability Monte-Carlo conformational searches and electrostatic calculations for peptides and proteins. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:983–1002. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kufareva I, Ilatovskiy AV, Abagyan R. Pocketome: an encyclopedia of small-molecule binding sites in 4D. Nucl Acids Res. 2012;40:D535–D540. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An JH, Totrov M, Abagyan R. Pocketome via comprehensive identification and classification of ligand binding envelopes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:752–761. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400159-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pauli J, Vag T, Haag R, Spieles M, Wenzel M, Kaiser WA, Resch-Genger U, Hilger I. An in vitro characterization study of new near infrared dyes for molecular imaging. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44:3496–3503. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagle JF, Tristram-Nagle S. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1469:159–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00016-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardt SL. Rates of diffusion controlled reactions in one, 2 and 3 dimensions. Biophys Chem. 1979;10:239–243. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(79)85012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melo E, Martins J. Kinetics of bimolecular reactions in model bilayers and biological membranes. A critical review. Biophys Chem. 2006;123:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wibo M, Amar-Costesec A, Berthet J, Beayfay H. Electron microscope examination of subcellular fractions III. Quantitative analysis of the microsomal fraction isolated from rat liver. J Cell Biol. 1971;51:52–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson ZE, Ellis SW, Edwards RJ, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Implications of the disparity in relative holo : apo-protein contents of different standards used for immuno-quantification of hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) Drug Metab Rev. 2005;37:77–77. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perrett HF, Barter ZE, Jones BC, Yamazaki H, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Disparity in holoprotein/apoprotein ratios of different standards used for immunoquantification of hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes. Drug Metab Disp. 2007;35:1733–1736. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu AM, Qu J, Felmlee MA, Cao J, Jiang XL. Quantitation of human cytochrome P450 2D6 protein with immunoblot and mass spectrometry analysis. Drug Metab Disp. 2009;37:170–177. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernando H, Davydov DR, Chin CC, Halpert JR. Role of subunit interactions in P450 oligomers in the loss of homotropic cooperativity in the cytochrome P450 3A4 mutant L211F/D214E/F304W. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamada M, Ohta Y, Bachmanova GI, Nishimoto Y, Archakov AI, Kawato S. Dynamic interactions of rabbit liver cytochromes P450IA2 and P450IIB4 with cytochrome b5 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase in proteoliposomes. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10113–10119. doi: 10.1021/bi00032a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schoch GA, Yano JK, Wester MR, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, Johnson EF. Structure of human microsomal cytochrome P4502C8 - Evidence for a peripheral fatty acid binding site. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9497–9503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinkovic DM, Ward A, Angove HC, Day PJ, Vonrhein C, Tickle IJ, Jhoti H. Crystal structures of human cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to metyrapone and progesterone. Science. 2004;305:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts AG, Atkins WM. Energetics of heterotropic cooperativity between alpha-naphthoflavone and testosterone binding to CYP3A4. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;463:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grinkova YV, Denisov IG, McLean MA, Sligar SG. Oxidase uncoupling in heme monooxygenases: Human cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 in Nanodiscs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430:1223–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ekroos M, Sjogren T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13682–13687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]