Abstract

Background

The impact of physicians’ disease-specific expertise on patient outcome is unknown. While previous studies suggest a survival advantage for cancer patients cared for at high volume centers, these observations may simply reflect referral bias or better access to advanced technologies, clinical trials, and multidisciplinary support at large centers.

Methods

We evaluated time to first treatment(TTFT) and overall survival(OS) of patients with newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma(CLL) at a single academic center based on whether they were cared for by a hematologist/oncologist who sub-specializes in CLL(CLL hematologist) or a hematologist/oncologist with expertise in other areas(non-CLL hematologist).

Results

Among 1309 newly diagnosed patients with CLL cared for between 1999–2009, 773(59%) were cared for by CLL hematologists and 536 were cared for by non-CLL hematologists. Among early stage patients(Rai 0-I), median TTFT(9.2 vs. 6.1 years; p<0.001) and OS(10.5 years vs. 8.8 years; p<0.001) were superior for patients cared for by CLL hematologists. For all patients, OS was superior for patients cared for by CLL hematologists(10.5 years vs. 8.4 years; p=0.001). Physician’s disease-specific expertise remained an independent predictor of OS after adjusting for age, stage, sex, and lymphocyte count. Patients seen by a CLL hematologist were also more likely participate in clinical trials(48% vs. 16%; p<0.001).

Conclusion

Physician disease-specific expertise appears to influence outcome in patients with CLL. To the greatest extent possible, patients should be cared for by a hematologist/oncologist expert in the care of their specific malignancy. When not possible, practice guidelines developed by disease-specific experts should be followed.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic lymphoma(CLL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), prognosis, physician expertise

BACKGROUND

The care of patients with cancer is becoming increasingly complex. Previous studies have demonstrated that the cancer outcomes of patients undergoing tumor resection may differ based on hospital volume and surgeon experience.1 Although less data are available regarding the outcome of cancers treated non-surgically, studies from both the U.S. and Europe suggest a survival advantage for patients with these cancers when cared for at high volume centers2–8 Despite these trends, insurance companies are pursing physician cost profiling as part of strategies to drive patients to the lowest cost provider rather than the most expert.9

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma(CLL),10, 11 the most prevalent lymphoid malignancy in the U.S., is one B-cell lymphoid malignancy that has seen significant clinical and scientific advances over the last decade.12–14 In addition to improved prediction of clinical outcome using biologic markers, a number of new therapies for treating the disease have reached the clinic. Alemtuzumab15, bendamustine16, ofatumumab17, and rituximab have all received FDA approval for treatment of CLL in the last decade which has also seen better definition of the role of allogeneic transplant for selected patients18. Multi-drug regimens combining chemotherapeutic agents with monoclonal antibodies have dramatically improved response rates, progression free survival,19–21 and overall survival(OS)22. There have also been considerable improvements in the understanding and management of complications of CLL including autoimmune hemolytic anemia(AIHA), immune thrombocytopenic purpura(ITP), pure red blood cell aplasia(PRBCA), hypogammaglobulinemia, and infectious complications.23, 24

Optimal application of new therapies and management of disease related complications requires significant expertise because age, comorbidities, prior therapies, and disease manifestations influence treatment selection for individual patients.12, 13 Consistent with this notion, evidence suggests that hospital volume and specialization may influence outcome in patients with lymphoma2 and recent population-based studies of lymphoma patients suggest that where a patient receives their care(e.g. rural versus metropolitan area; community based versus university-based) may influence survival.25 While these observations could be due to greater disease-specific expertise among physicians at university and large metropolitan centers, they may simply reflect referral bias or better access to advanced technologies, clinical trials, supportive care, and multidisciplinary support at large centers. Little is known about the direct influence of the hematologist/oncologist’s disease-specific expertise on the outcome of patients cared for in the same practice setting where access to clinical trials, multidisciplinary consultation, and medical technologies are identical.

We hypothesized that the hematologist/oncologist’s disease-specific expertise would influence the time to first treatment(TTFT) and choice of therapy in patients with CLL including the small lymphocytic lymphoma(SLL) variant, but would not influence OS. As part of a quality initiative, we evaluated TTFT, therapy selection, and OS in patients with newly diagnosed CLL cared for at the same academic medical center based on whether they were seen by a hematologist/oncologist who specifically focused on caring for patients with CLL or by a hematologist/oncologist with expertise in other areas.

METHODS

Physician Disease-specific Expertise

The Mayo Clinic Division of Hematology is comprised of 43 hematologists caring for the full spectrum of benign and malignant hematologic diseases. Among these physicians, 42(98%) are board-certified in hematology. During the study interval, 29(67%) of these physicians were also board-certified in medical oncology(1 physician certified medical oncology only; remaining 28 certified both hematology and medical oncology). Like most academic centers, although qualified to care for the full spectrum of blood disorders, physicians develop focused expertise within a specific disease area. The Mayo Clinic Division of Hematology is organized around 6 disease groups which focus on chronic lymphoproliferative disorders(e.g. CLL), dysproteinemias(e.g. myeloma, amyloidosis), lymphoma, myeloid diseases(e.g. leukemia, myelodysplasia), bleeding/coagulation disorders, and nonmalignant hematology. During scheduling, effort is made for patients to be seen by a physician within the disease group most specific to their diagnosis. If, however, there is a long wait for a patient to be seen by a disease-specific physician, patients may be seen by a hematologist outside that disease group.

Patients

The Mayo Clinic CLL Database includes all patients with a diagnosis of CLL11 or SLL26 seen in the Division of Hematology at Mayo Clinic Rochester who permit their records to be used for research purposes.23, 27–33 All these patients fulfilled the 1996 criteria for CLL in effect through the study period26 and/or the WHO criteria for SLL11. Clinical information regarding date of diagnosis, physical examination, clinical stage(Rai), prognostic parameters, and treatment history are abstracted from clinical records at the time of inclusion and maintained on a prospective basis. Results of prognostic testing performed as part of clinical or research studies are also included in the database. This includes evaluation of absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), IGHV gene mutation analysis, ZAP70 status, CD38 status, and cytogenetics abnormalities by interphase FISH testing using methods previously described by our group.34–37

With the approval of the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, we used this database to identify all patients with previously untreated CLL cared for in the Division of Hematology between January 1999 and September 2009. Only patients seen within 1 year of diagnosis were included in this analysis. For each patient, charts were reviewed to identify the treating hematologist or hematology/oncology fellow responsible for the patient’s care at the time of their initial consultation as well as their primary disease group affiliation. Hematologists who were members of the CLL disease group were designated as having disease-specific expertise(“CLL hematologist”) while hematologists who were primary members of other disease groups were considered as having expertise in other areas(“non-CLL hematologist”). During the time interval for the present study, the CLL/chronic lymphoproliferative disorder disease group was comprised of 5 hematologists. Patients cared for by a nurse practitioner(NP) who is a member of the CLL disease group and is supervised by CLL hematologists were also classified as being cared for by a CLL hematologist. Patients cared for by fellows were classified based on whether the supervising physician was a CLL hematologist or a non-CLL hematologist using accurate computer documentation. Per institutional policy, all patients cared for by fellows are seen in person by the supervising hematologist at the time of the initial consultation. If a patient was initially seen by a non-CLL hematologist but was immediately referred to a CLL hematologist to assume care, they were classified as being cared for by a CLL hematologist.

For patients who went on to receive chemotherapy treatment, charts were also reviewed to determine the primary disease group of the treating physician at the time therapy was initiated using the same classification scheme. Therapies were grouped into one of five categories: purine nucleoside analog based therapy, single-agent alkylator therapy(+/− steroid), non-purine analogue-alkylating agent based combination, antibody-only therapy, or other therapy.

Statistical methods

Differences in patients’ clinical characteristics by physician type(CLL vs non-CLL) were analyzed using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests for discrete variables or using t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. OS was defined as the time between the date of diagnosis to date of death or last follow-up, and TTFT was defined as the time between the date of diagnosis and date of initiation of first treatment or date of last follow-up at which the patient was known to be untreated. Although, the accepted indications to initiate treatment throughout the study interval were based on the NCI-WG 1996 criteria26, these criteria provide substantial latitude for physician judgment with respect to what represents “progressive or massive lymphadenopathy” and interpretation of the clinical significance of constitutional symptoms such as fatigue. Patients receiving early treatment as part of experimental protocols prior to meeting NCI-WG 1996 criteria to initiate therapy were censored as untreated on the date experimental therapy was administered for analysis of TTFT (since they had not met criteria for treatment as of that date) but were included in survival analysis. Repeat analysis of TTFT and OS in which these patients were removed altogether (rather than censored) led to similar results. Estimates of survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional hazard models were used to model the relationship of multiple variables simultaneously. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS 9.1 software package(SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

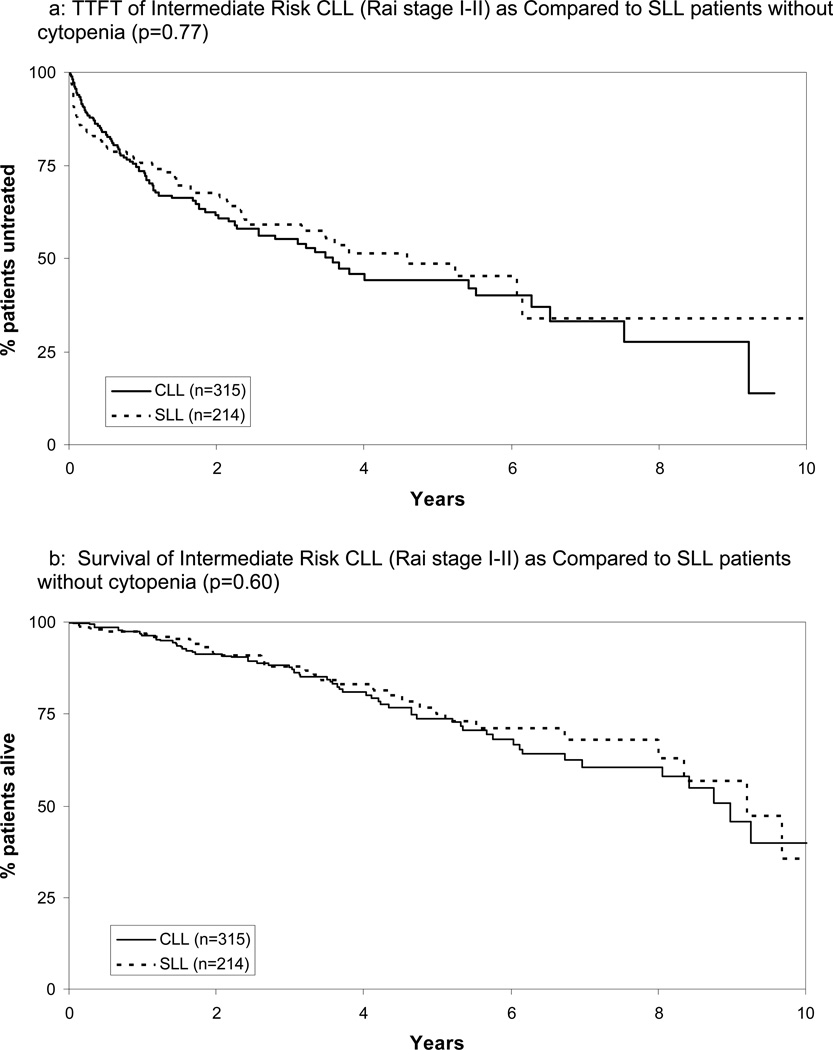

Between January 1999 and September 2009, 1309 previously untreated patients with CLL(SLL variant n=238) who presented within 1 year of diagnosis were seen in the Mayo Clinic Division of Hematology. Median time from diagnosis to consultation at Mayo Clinic was 11 days. Consistent with previous reports38 and the WHO classification of CLL and SLL as a single disease entity11, there was no difference in TTFT or OS between patients with the SLL variant and comparable stage(Rai I or II) CLL(Figure 1). Accordingly, for staging purposes, patients with SLL who did not have cytopenias were grouped with intermediate Rai risk(stage I and II) patients while those with cytopenias were grouped with high Rai risk(stage III or IV) patients.

Figure 1.

TTFT and Survival of Intermediate Risk CLL (Rai stage I-II) as Compared to SLL patients without cytopenia

Among these 1309 patients, 773(59%) were cared for by a CLL hematologist either directly(n=664) or by a fellow supervised by a CLL hematologist(n=109). The remaining patients were cared for by a hematologist with primary expertise in an area other than CLL(n=429) or by a fellow supervised by a non-CLL hematologist(n=107). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients seen by non-CLL hematologists were slightly older and more likely to have intermediate Rai risk but on average had lower ALCs. No difference in the geographic proximity of patients’ residence to Mayo Clinic was observed between groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Non-CLL MD (n=536) |

CLL MD (n=773) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age at Diagnosis (range) | 66.3 (38–95) | 63.2 (28–97) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 347 (62%) | 513 (66%) | 0.54 | |

| Rai Risk at diagnosis | ||||

| Low (Rai stage 0) | 242 (46%) | 457 (59%) | <0.001 | |

| Intermediate (Rai stage I–II) | 267 (50%) | 286 (37%) | ||

| High (Rai stage III–IV) | 23 (4%) | 26 (3%) | ||

| Missing | 4 | 4 | ||

| ALC (× 109/L), median | 7.1 | 9.8 | ||

| ≤30 | 451 (93%) | 634 (86%) | <0.001 | |

| >30 | 36 (7%) | 104 (14%) | ||

| Missing | 49 | 35 | ||

| Proximity Patient Residence to Mayo Clinic | ||||

| <120 miles (e.g. 2 hour drive) | 238 (45%) | 361 (48%) | 0.29 | |

| <300 miles (e.g. 5 hour drive) | 401 (76%) | 570 (76%) | 0.98 | |

| Missing | 8 | 22 | ||

| Received stem cell transplant during course* | 6 (1.1%) | 8 (1.0%) | 1.0 | |

in total 14/1309 patients (1.1%) received stem cell transplant (11 allogenic; 3 autologous)

Patient seen by CLL hematologists were markedly more likely to undergo prognostic evaluation using molecular biomarkers including CD38 (performed 93% vs. 76%; p<0.0001), ZAP70 (69% vs. 40%; p<0.0001), cytogenetic analysis by FISH (79% vs. 53%; <0.0001), CD49d (41% vs. 20%; p<0.0001), and IGHV gene mutation testing (67% vs. 25%; p<0.0001). Prognostic evaluation using molecular biomarkers was non random among non-CLL hematologists and was more likely to be performed in patients whose disease had more aggressive clinical characteristics. For example, the Rai stage 0/I patients cared for by non-CLL hematologists who had CD38, CD49d, or ZAP70 testing performed had a shorter TTFT irrespective of the assay results (e.g. simply having the test performed predicted for shorter TTFT regardless of whether the test result was favorable or unfavorable; all p<0.05). Similarly, those patients who had IGHV, FISH, CD49d, or ZAP70 testing performed had shorter OS than those who did not have these assays performed (e.g. having the test performed predicted poorer survival regardless of whether the test result was favorable or unfavorable, all p <0.05). Because these prognostic tests i) were missing in large numbers of patients, ii) were markedly more likely to be missing for patients cared for by non-CLL hematologists, and iii) were not missing at random among non -CLL hematologists, further analysis of the impact of prognostic testing on clinical outcomes by physician expertise could not be reliably performed.

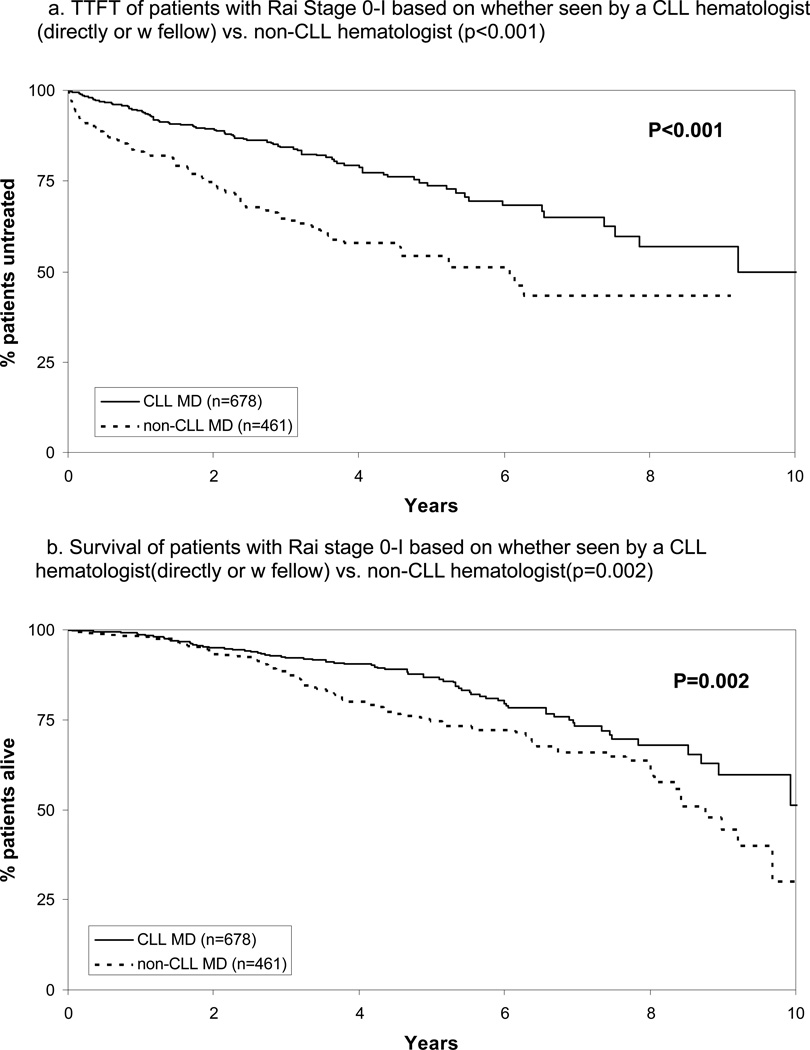

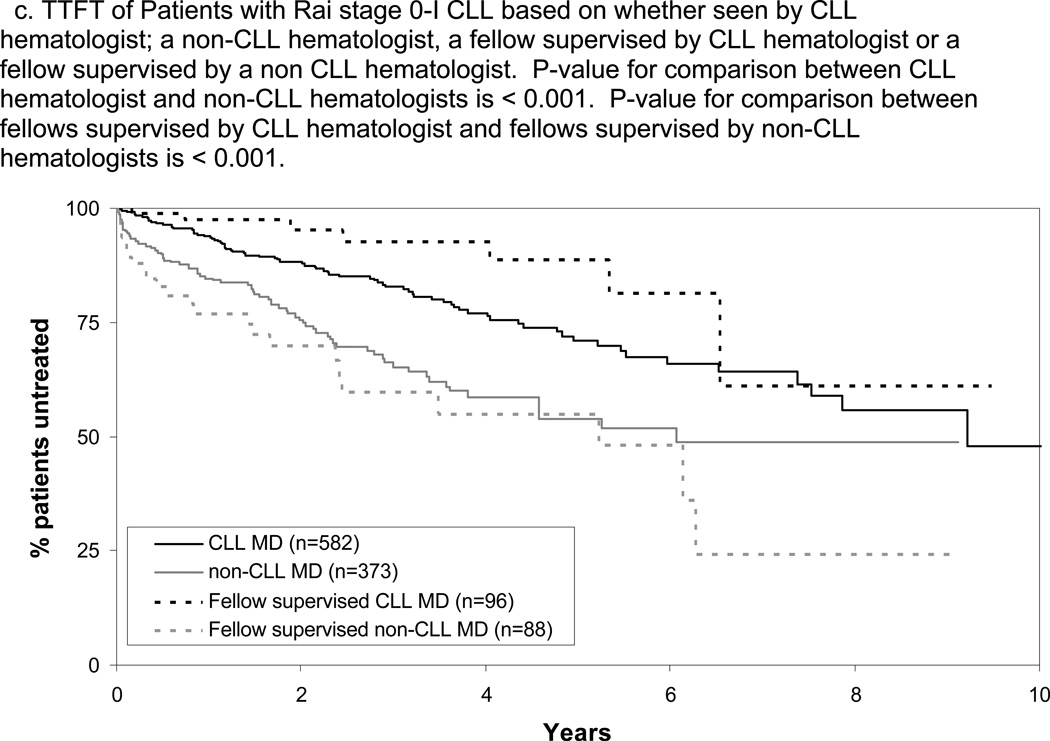

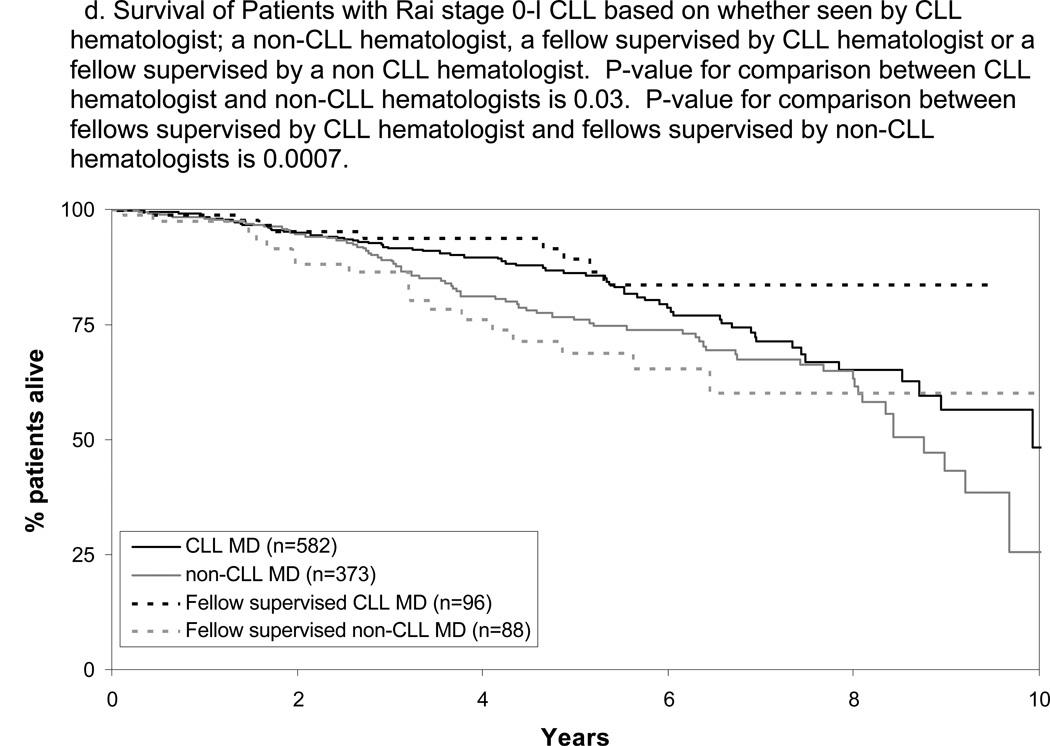

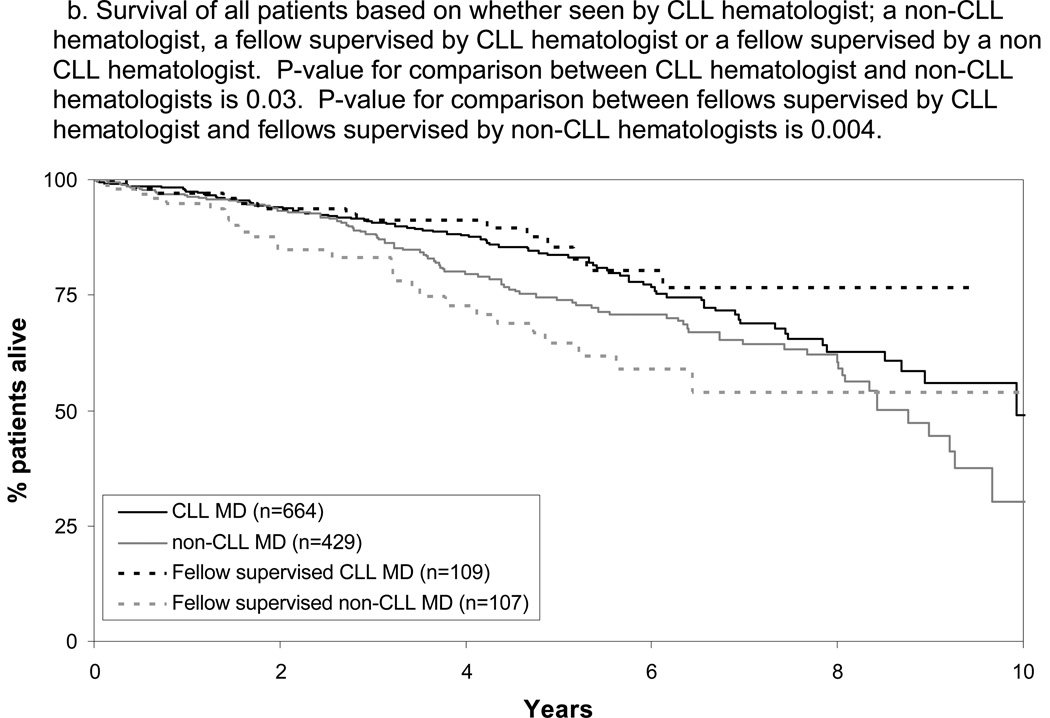

In aggregate, 1139 patients had Rai stage 0-I disease and were the principle candidates for observation(“watchful-waiting”).26 Among these, 678(60%) were cared for by a CLL-hematologist either directly(n=582) or by a fellow supervised by CLL hematologist(n=96). The remaining 461 were cared for by a non-CLL hematologist(n=373) or by a fellow supervised by a non-CLL hematologist CLL(n=88). TTFT and OS of patients with Rai stage 0-I CLL/SLL based on the type of physician caring for them is shown in Figure 2A and B. The median TTFT was 9.2 years for patients cared for by a CLL hematologist as compared to 6.1 years when cared for by a non-CLL hematologist(p<0.001). When patients with Rai stage 0 and I were analyzed separately, TTFT remained shorter for both patients with Rai stage 0 (p=0.043) and Rai stage 1 (p<0.001) disease. The median OS of patients cared for by a CLL hematologist was 10.5 years as compared to 8.8 years for those cared for by a non-CLL hematologist(p=0.002). When patients with Rai stage 0 and I were analyzed separately, OS remained shorter for those with Rai stage 1 disease (p=0.03) however the difference for those with Rai stage 0 did not reach the threshold of statistical significance (p=0.08).

Figure 2.

TTFT and OS Among Rai Stage 0-I Patients

The TTFT and OS of patients cared for by fellows differed based on the disease-specific expertise of the supervising physician with superior TTFT and OS when fellows were supervised by CLL hematologists(Figure 2C and D; p-value TTFT<0.001; p-value OS=0.007). Patients cared for by fellows supervised by a CLL hematologist had slightly longer TTFT(p=0.04) and similar OS(p=0.16) as patients cared for directly by CLL hematologists. Patients cared for by fellows supervised by a non-CLL hematologist had similar TTFT(p=0.16) and OS(p=0.46) as patients cared for directly by non-CLL hematologists. The relationship between physician disease-specific expertise and outcome among Rai stage 0–I patients remained significant on multivariate analysis adjusting for age, sex, stage, ALC at the time of initial consultation, and whether or not patients were cared for by a fellow (Table 2; p-value TTFT<0.001; p-value OS=0.01).

Table 2.

Multivariate Model of Time to First Treatment and Overall Survival from Diagnosis Among Patients with Rai Stage 0-I Disease

| TIME TO FIRST TREATMENT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard ratio4 | 95% C.I. | p-value |

| Age1 | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.02) | 0.72 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.56 | (1.11, 2.18) | 0.01 |

| ALC2 | 1.016 | (1.012, 1.021) | <0.001 |

| Rai Stage 1 vs 0 | 2.85 | (2.10, 3.86) | <0.001 |

| Fellow (Fellow vs MD) 3 | 0.94 | (0.64, 1.39) | 0.75 |

| MD (non-CLL vs CLL) | 2.38 | (1.74, 3.26) | <0.001 |

| OVERALL SURVIVAL | |||

| Variable | Hazard ratio4 | 95% C.I. | p-value |

| Age1 | 1.07 | (1.05, 1.09) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.39 | (0.97, 1.98) | 0.07 |

| ALC2 | 1.011 | (1.006, 1.017) | <0.001 |

| Rai Stage 1 vs 0 | 1.57 | (1.13, 2.19) | 0.007 |

| Fellow (Fellow vs MD) 3 | 0.98 | (0.64, 1.50) | 0.94 |

| MD (non-CLL vs CLL) | 1.49 | (1.08, 2.04) | 0.01 |

Hazard ratio for each 1 year older

Hazard ratio for each 1 × 109/L increase in ALC

Fellow versus staff hematologist

HR>1 indicate a shorter TTFT or overall survival

During the study interval, 320(24%) patients received therapy. Of these, 92 had their first treatment under the direction of a non-Mayo physician or were treated prior to disease progression as part of clinical trials testing early intervention(n=44) and were excluded from analysis on type of first-line therapy. Among the remaining 184 patients, 104 had their first treatment selected by a CLL hematologist while the remaining 80 had their first treatment selected by a non-CLL hematologist. Patients seen by a CLL hematologist were markedly more likely to receive their first-line treatment as part of a clinical trial(48% vs. 16%; p<0.001). The type of first-line therapy administered differed based on physician disease-specific expertise(p<0.001) with CLL hematologists more likely to administer purine nucleoside analogue based treatment(70% vs. 28%) and less likely to administer a non-purine alkylating agent combination(8% vs. 28%), single agent alkylator(12% vs. 22%), or anti-body only therapy +/− steroids(10% vs. 19%).

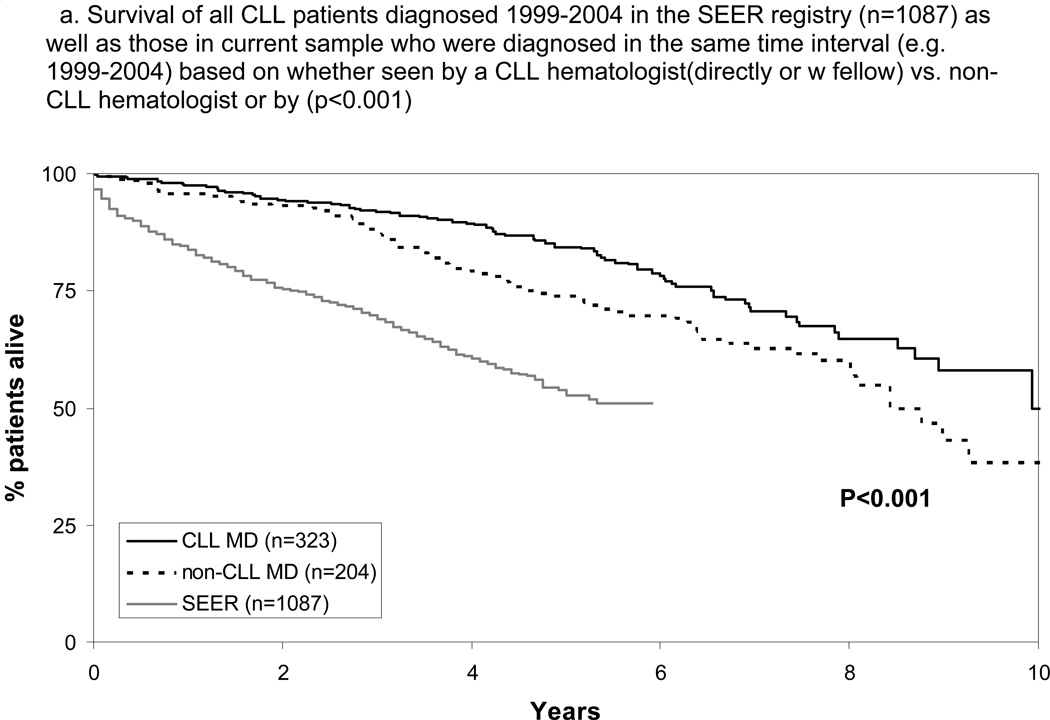

Finally, we evaluated the OS of patients of all disease stages. Consistent with previous reports2,25 and potentially due to referral bias, survival of patients cared for at Mayo Clinic was longer than patients in the SEER registry(n=1087) diagnosed with CLL 1999–2004(Figure 3A). For all patients (January 1999 – September 2009), median OS of patients cared for by a CLL hematologist(directly or with fellow) was 10.5 years as compared to 8.4 years(p=0.001) for those cared for by a non-CLL hematologist(directly or with fellow). OS of patients cared for by a fellow again differed based on the disease-specific expertise of the supervising physician with superior survival when fellows were supervised by a CLL hematologist(Figure 3B; p=0.004). Physician disease-specific expertise remained a significant factor for OS after adjusting for age, sex, stage, ALC at diagnosis, and whether or not patients were cared for by a fellow (p=0.04; Table 3). All multivariate results were similar when SLL patients were excluded from the analysis or treated as a separate stage category(rather than grouped with Rai stage I-II CLL) with physician disease-specific expertise remaining an independent predictor of TTFT and OS in all models(all p≤0.014). TTFT for all patients was also shorter for patients cared for by a non-CLL hematologists (5.2 vs. 9.2 years; p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Survival All Patients

Table 3.

Multivariate Model Overall Survival from Diagnosis All Patients

| OVERALL SURVIVAL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard ratio4 | 95% C.I. | p-value |

| Age1 | 1.07 | (1.06, 1.09) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.66 | (1.20, 2.29) | 0.002 |

| ALC2 | 1.002 | (0.999, 1.005) | 0.12 |

| Rai Stage 3/4 vs 0 | 3.66 | (2.28, 5.87) | <0.001 |

| Rai Stage 1/2 vs 0 | 1.61 | (1.18, 2.18) | 0.002 |

| Fellow (Fellow vs MD) 3 | 1.19 | (0.83, 1.70) | 0.34 |

| MD(non-CLL vs CLL) | 1.36 | (1.02, 1.81) | 0.04 |

Hazard ratio for each 1 year older

Hazard ratio for each 1 × 109/L increase in ALC

Fellow versus staff hematologist

HR>1 indicate a shorter overall survival

DISCUSSION

Our study is unique in that it evaluates clinical outcome based on physician’s disease specific expertise in a large cohort of newly diagnosed (≤1 year) patients with a single type of lymphoid malignancy all cared for at the same medical center where treating hematologists/oncologists had identical access to clinical trials, technology, supportive care, and multidisciplinary consultation. Several findings of the study are notable. First, although all treating/supervising physicians were board certified hematologists/oncologists, significant differences in clinical management and disease outcome were observed based on physician’s disease-specific expertise. Earlier stage (Rai 0-I) patients cared for by a disease-specific expert had a longer TTFT, received different types of therapy when treatment was initiated, and were markedly more likely to participate in a clinical trial. Second, patients cared for by physicians with disease-specific expertise also had longer OS, a finding that persisted on multivariate analysis controlling for other prognostic factors. This finding suggests that the expertise of the physician caring for the patient with CLL/SLL is an independent prognostic variable. Third, the clinical outcomes of patients cared for by hematology fellows at our center differed according to the disease-specific expertise of the supervising physician; a powerful internal validation of the importance of disease-specific expertise. The patients cared for by fellows were being cared for by the same physicians (e.g. each fellow can care for multiple CLL patients) however patient management and outcome differed based on the expertise of the physician supervising/advising the fellow.

Although we are unable to definitively identify the reasons for a difference in OS based on physician’s disease-specific expertise in this observational study, a number of possible explanations are apparent. First, a longer TTFT was observed for earlier stage patients when cared for by a CLL physician. Similar observations were reported by Tsimberidou and colleagues for CLL/SLL patients cared for at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.38 This finding persisted for both Rai stage 0 or Rai stage 1 patients when analyzed independently and may reflect different application of the NCI Working Group criteria among CLL experts and non-experts, particularly regarding what constitutes “massive/progressive lymphadenopathy” and/or whether physicians treat for a progressive lymphocytosis. Early treatment exposes patients to the toxic effects of therapy which places them at risk for a variety of treatment related complications including infection, second malignancy, and myelodysplasia, and may also induce clonal selection that renders their leukemia more resistant to future treatment. Second, when patients received therapy, the type of treatment they received differed based on the disease-specific expertise of their physician with CLL hematologists more likely to use purine nucleoside analog regimens. Although in early follow-up Phase III trials suggested no difference in survival based on whether patients received purine analogs as compared to alkylating agent based regimens39–41, recently updated results suggest a survival advantage to patients receiving first-line purine analog based therapy.42 Third, CLL experts may be more likely to administer salvage therapy(including multiple salvage attempts) for patients with progressive disease. Fourth, CLL experts may recognize disease-specific complications(e.g. CMV reactivation, ITP, AIHA) earlier and provide better management of these complications.

While it is obviously ideal for patients to be cared for by the physician with the greatest knowledge and experience relevant to their condition, this is often not possible or practical. Although some have suggested regionalization of cancer care to centers of excellence for patients with specific malignancies,25 this controversial topic is not the focus of our paper. Our results do suggest, however, that wherever they are seen, patients should ideally be cared for by the hematologist/oncologist in their community with the greatest disease-specific expertise. Consistent with this approach, many large community oncology practices encourage oncologists to develop a disease-specific expertise similar to the long-standing pattern at academic centers. Collaborative management between a local hematologist/oncologist and CLL expert may also be a good model as the data on patients cared for by fellows at our center suggest it is not necessary patients be managed directly by a disease expert provided the expert can provide counsel to the treating physician. In this regard, the physician charge for a second opinion by a disease expert is a relatively low cost intervention(~$600), roughly 1% of the average wholesale price of 6 cycles of first-line CLL therapy.43 When a disease specific expert is not available, patients should be managed according to published treatment guidelines developed by expert panels.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. First, the study was restricted to patients with CLL/SLL, and our results are not necessarily applicable to patients with other malignancies. Although some aspects of CLL management are different than most other cancers(e.g. observation for asymptomatic early stage patients), we doubt the importance of physician disease specific expertise is unique to CLL. Second, although the survival differences we observed persisted on multivariate analysis controlling for age, stage, sex, and ALC, other unmeasured confounding variables could exist. For example, we could not control for differences in biologic prognostic variables(e.g. ZAP70 expression, IGHV gene mutation status, genetic defects detected by FISH) since many patients did not have these tests performed, they were markedly less likely to be performed by non-CLL hematologists, and they were not missing at random among patients seen by non -CLL hematologists. These tests were not used to make treatment decisions during the study interval and, since they were not considered in patient scheduling, it is believed they were evenly distributed among patients cared for by CLL and non-CLL hematologists. Third, we classified treatment provider at the time of diagnosis/initial consultation and at initiation of first therapy which are two of the most objectively defined time-points in the CLL disease course but which cannot completely account for complex patterns of shifting care and referrals. We attempted to minimize the influence of any referral bias by limiting the analysis to patients seen within 1 year of diagnosis. Fourth, we used physician’s primary disease group to designate disease-specific expertise, an imperfect classification since some physicians outside the disease group cultivate expertise. Nonetheless, this would bias toward a negative rather than positive result. Finally, although patient assignment to a CLL or non-CLL physician during the study was generally random(e.g. made by appointment secretaries based on schedule availability), the study represents a retrospective series rather than a prospective, controlled trial.

In conclusion, hematologist/oncologist disease-specific expertise appears to influence the survival of patients with CLL/SLL even when seen in the setting of an academic center. In the era of physician cost profiling and pay for performance oriented health care reform,9 care by a disease specific expert appears to provide value to patients. To the greatest extent possible, patients should be seen by a board certified hematologist/oncologist expert in the care of their specific malignancy. When this is not possible, practice guidelines developed by disease-specific experts should be followed.

Acknowledgments

Support through grants from the National Cancer Institute(CA 113408 to T.D. Shanafelt) and Gabrielle's Angel Foundation for Cancer Research(T.D. Shanafelt), and The Henry J. Predolin Foundation are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Employment or Leadership Position: None

Consultant or Advisory Role: None

Stock Ownership: None

Honoraria: None

Research Funding: None

Expert Testimony: None

Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Tait Shanafelt

Financial support: Tait Shanafelt

Administrative support: Tait Shanafelt, Susan Schwager

Provision of study materials or patients: Tait Shanafelt, Neil Kay, David Inwards, Clive Zent, Carie Thompson, Tom Witzig, Tim Call

Collection and assembly of data: Tait Shanafelt, Susan Schwager, Kari Rabe, Susan Slager

Data analysis and interpretation: Kari Rabe, Susan Slager, Tait Shanafelt, Tim Call, Clive Zent, Neil Kay, Jose Leis, Deborah Bowen, David Inwards, Carie Thompson, Tom Witzig,

Manuscript writing: Tait Shanafelt

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(11):2327–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis S, Dahlberg S, Myers MH, Chen A, Steinhorn SC. Hodgkin's disease in the United States: a comparison of patient characteristics and survival in the Centralized Cancer Patient Data System and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78(3):471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feuer EJ, Frey CM, Brawley OW, et al. After a treatment breakthrough: a comparison of trial and population-based data for advanced testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(2):368–377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding MJ, Paul J, Gillis CR, Kaye SB. Management of malignant teratoma: does referral to a specialist unit matter? Lancet. 1993;341(8851):999–1002. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91082-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collette L, Sylvester RJ, Stenning SP, et al. Impact of the treating institution on survival of patients with "poor-prognosis" metastatic nonseminoma. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genito-Urinary Tract Cancer Collaborative Group and the Medical Research Council Testicular Cancer Working Party. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(10):839–846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.10.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aass N, Klepp O, Cavallin-Stahl E, et al. Prognostic factors in unselected patients with nonseminomatous metastatic testicular cancer: a multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(5):818–826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.5.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horowitz MM, Przepiorka D, Champlin RE, et al. Should HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplants for leukemia be restricted to large centers? Blood. 1992;79(10):2771–2774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayanian JZ, Guadagnoli E. Variations in breast cancer treatment by patient and provider characteristics. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;40(1):65–74. doi: 10.1007/BF01806003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JL, Mehrotra A, Thomas JW, McGlynn EA. Physician cost profiling--reliability and risk of misclassification. N Engl J Med. 362(11):1014–1021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0906323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gribben JG. How I treat CLL upfront. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-207126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt TD, Kay NE. Comprehensive Management of the CLL Patient: A Holistic Approach. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007;2007:324–331. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiorazzi N, Rai KR, Ferrarini M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):804–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillmen P, Skotnicki AB, Robak T, et al. Alemtuzumab compared with chlorambucil as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5616–5623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Phase III randomized study of bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4378–4384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wierda WG, Kipps TJ, Mayer J, et al. Ofatumumab as single-agent CD20 immunotherapy in fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1749–1755. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorror ML, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(30):4912–4920. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keating M, O'brien S, Albitar M, et al. Early Results of a Chemoimmunotherapy Regimen of Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, and Rituximab as Initial Therapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4079–4088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallek M. Immunochemotherapy with Fludarabine (F), Cyclophosphamide (C), and Rituximab (R) (FCR) Versus Fludarabine and Cyclophosphamide (FC) Improves Response Rates and Progression-Free Survival (PFS) of Previously Untreated Patients (pts) with Advanced Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Blood. 2008;112 Abstract #325. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kay NE, Geyer SM, Call TG, et al. Combination chemoimmunotherapy with pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab shows significant clinical activity with low accompanying toxicity in previously untreated B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(2):405–411. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zent CS, Ding W, Schwager SM, et al. The prognostic significance of cytopenia in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(5):615–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison VA. Management of infectious complications in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007;2007:332–338. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loberiza FR, Jr., Cannon AJ, Weisenburger DD, et al. Survival disparities in patients with lymphoma according to place of residence and treatment provider: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5376–5382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, et al. National Cancer Institute-Sponsored Working Group Guidelines fo Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Reised Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanafelt TD, Kay NE, Jenkins G, et al. B-cell count and survival: Differentiating chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) from monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) based on clinical outcome. Blood. 2009;113:4188–4196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-176149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanafelt TD, Jenkins G, Call TG, et al. Validation of a new prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2009;115(2):363–372. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanafelt TD, Rabe KG, Kay NE, et al. Age at diagnosis and the utility of prognostic testing in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/cncr.25292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maddocks-Christianson K, Slager SL, Zent CS, et al. Risk factors for development of a second lymphoid malignancy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;139(3):398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thurmes P, Call T, Slager S, et al. Comorbid conditions and survival in unselected, newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(1):49–56. doi: 10.1080/10428190701724785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowen DA, Call TG, Jenkins GD, et al. Methylprednisolone-rituximab is an effective salvage therapy for patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia including those with unfavorable cytogenetic features. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(12):2412–2417. doi: 10.1080/10428190701724801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer S, Hanson CA, Zent CS, et al. Prognostic importance of T and NK-cells in a consecutive series of newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(5):607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanafelt TD, Geyer SM, Bone ND, et al. CD49d expression is an independent predictor of overall survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a prognostic parameter with therapeutic potential. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(5):537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewald G, Brockman S, Paternoster S, et al. Chromosome anomalies detected by interphase fluorscence in hybridization: correlation with significant biological features of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2003;121:287–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jelinek DF, Tschumper RC, Geyer SM, et al. Analysis of clonal B-cell CD38 and immunoglobulin variable region sequence status in relation to clinical outcome for B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;115(4):854–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shanafelt TD, Witzig TE, Fink SR, et al. Prospective evaluation of clonal evolution during long-term follow-up of patients with untreated early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4634–4641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, O'Brien S, et al. Assessment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma by absolute lymphocyte counts in 2,126 patients: 20 years of experience at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4648–4656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rai K, Peterson B, Appelbaum F, et al. Fludarabine compared with chlorambucil as primary therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1750–1757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson S, Smith AG, Loffler H, et al. Multicentre prospective randomised trial of fludarabine versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CAP) for treatment of advanced-stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. The French Cooperative Group on CLL. Lancet. 1996;347(9013):1432–1438. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leporrier M, Chevret S, Cazin B, et al. Randomized comparison of fludarabine, CAP, and ChOP in 938 previously untreated stage B and C chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Blood. 2001;98(8):2319–2325. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rai K, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, et al. Long-term Survival Analysis of the North American Intergroup Study C9011 Comparing Fludarabine (F) and Chlorambucil (C) in Previously Untreated Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Blood. 2009;114 Abstract 536. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shanafelt TD, Gunderson H, Call TG. Commentary: chronic lymphocytic leukemia--the price of progress. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):601–602. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]