Abstract

Experimental evidence provides strong support for anti-carcinogenic effects of calcium and vitamin D with respect to breast cancer. Observational epidemiologic data also provide some support for inverse associations with risk. We tested the effect of calcium plus vitamin D supplementation on risk of benign proliferative breast disease, a condition which is associated with increased risk of breast cancer. We used the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. The 36,282 participants were randomized either to 500 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate plus 200 IU of vitamin D3 (GlaxoSmithKline) twice daily (n = 18,176) or to placebo (n = 18,106). Regular mammograms and clinical breast exams were performed. We identified women who had had a biopsy for benign breast disease and subjected histologic sections from the biopsies to standardized review. After an average follow-up period of 6.8 years, 915 incident cases of benign proliferative breast disease had been ascertained, with 450 in the intervention group and 465 in the placebo group. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation was not associated with altered risk of benign proliferative breast disease overall (hazard ratio = 0.99, 95% confidence interval = 0.86–1.13), or by histologic subtype. Risk varied significantly by levels of age at baseline, but not by levels of other variables. Daily use of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate plus 400 IU of vitamin D3 for almost 7 years by postmenopausal women did not alter the overall risk of benign proliferative breast disease.

Keywords: Calcium, Vitamin D, Benign proliferative breast disease

Introduction

Breast cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and the most commonly diagnosed neoplasm (except for non-melanoma skin cancer) among women worldwide [1]. Given this, substantial effort is being devoted to the identification of methods for the primary prevention of breast cancer, particularly by means of chemopreventive interventions [2]. In this regard, the potential chemopreventive properties of calcium and vitamin D have elicited considerable interest given both experimental evidence supporting their anti-carcinogenic effects and observational epidemiologic data providing some support for inverse associations with breast cancer risk [3].

Given the long latency of breast cancer development [4], trials that evaluate the effects of chemopreventive agents with respect to breast cancer may require a long follow-up period to demonstrate associations if the agents act at an early stage in the carcinogenic process. However, this does not preclude observation of an effect on earlier stages in the natural history of breast cancer after shorter follow-up periods. Therefore, we used the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomized, controlled trial of calcium plus vitamin D (CaD) supplementation to examine the effect of this intervention on risk of benign proliferative breast disease, a condition which is associated with increased risk of and may be on the pathway to invasive breast cancer [4–7].

Materials and methods

Study population

The eligibility criteria and recruitment methods for the WHI CaD trial have been described elsewhere [8–10]. In brief, women who were participants either in the WHI dietary modification (DM) or in the hormone therapy (HT) trials, or in both, were invited to join the CaD trial at their first or second annual follow-up visit. DM and HT trial participants were postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years at initial screening who were likely to reside in the area for 3 years, and who provided written informed consent [11–14]. They were enrolled in the WHI between 1993 and 1998 at 40 clinical centers throughout the United States. Exclusion criteria for these trials were related to competing risks, and safety, adherence and retention considerations. For the CaD trial, additional exclusion criteria included a history of renal calculi or hypercalcemia, current use of oral corticosteroids, and current daily use of more than 600 IU of supplemental vitamin D or calcitriol [8]. Of the 68,132 participants in the DM or HT trials, 31,850 were either ineligible for or refused to participate in the CaD trial. A total of 36,282 women were randomized, of whom 25,210 (69%) were in the DM trial and 16,089 (44%) were in one of the two HT trials; 14% of participants were in both the DM trial and one of the HT trials. Of those who joined the CaD trial, 91% did so during their first annual visit, and the remainder joined during the following year. All participants had a baseline mammogram and clinical breast examination on entry into the DM or HT trials; abnormal findings required clearance before entry into the WHI. The WHI and the ancillary study reported here (in which all 40 WHI clinical centers participated) were approved by institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

Study regimens, randomization, and blinding

Of the 36,282 participants in the CaD trial, 18,176 were assigned randomly to receive one tablet of 500 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate combined with 200 IU of vitamin D3 (GlaxoSmithKline) twice daily (yielding a daily total of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D3), while the remaining 18,106 received an identical-appearing placebo tablet twice daily. Randomization involved use of a permuted block algorithm, stratified by clinic and age. All medication bottles had unique bar codes and computer-based selection to ensure blinded dispensing.

Baseline data collection, follow-up, and assessment of adherence

Comprehensive information on breast cancer risk factors was obtained at baseline by interview (for lifetime hormone use) and by self-report for (other covariates) using standardized questionnaires [12].

Participants were contacted by telephone after 4 weeks to assess symptoms and reinforce adherence. Thereafter, follow-up contacts by telephone or clinic visit occurred every 6 months, with clinic visits required annually. Mammograms were required annually (for women in the HT trials) or biennially (for women in the DM trial); in the HT trials, study medications were withheld if the mammograms were not performed or results could not be verified, but participants continued to be followed. Clinical breast examinations were performed annually by study personnel or by referral to the participant’s private health care provider.

Adherence was assessed by weighing returned pill bottles. Study medication was discontinued if kidney stones, hypercalcemia, dialysis, or use of calcitriol or daily supplements of more than 1,000 IU of vitamin D was reported [9]. All participants continued to be followed up, regardless of their level of adherence.

Ascertainment of outcome

The outcome of interest for the present study was histo-logically confirmed incident benign proliferative breast disease with or without atypia (see ‘‘Histology’’). Clinical events, including breast cancers and breast biopsies for non-cancerous lesions, were initially identified from self-administered questionnaires completed every 6 months. Breast cancers were confirmed by local and central adjudicators, who reviewed medical records and pathology reports and who were blinded both to treatment assignment and to symptoms due to study medications. For the present study, women who reported breast biopsies that were free of cancer were identified and clinical centers were sent lists of potentially eligible subjects quarterly. Clinic staff contacted participants to obtain written informed consent to solicit the histologic sections resulting from the biopsies. To investigate the possibility that breast biopsies were missed by using this approach, the charts of 100 randomly selected participants who did not report breast biopsy were reviewed at one center and none was found to have unreported biopsies.

Histology

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained histologic sections were reviewed by the study pathologist (D.L. Page), who was blinded to the randomization assignment. The benign lesions were classified using well-established criteria as non-proliferative lesions, proliferative lesions without atypia (classified further according to whether they were mild, moderate, or florid in extent), or atypical (ductal/ lobular) hyperplasia [15–17].

Statistical analysis

Incidence rates of benign proliferative breast disease in the CaD supplementation and placebo groups were compared based on the intention-to-treat principle using time-to-event analyses. The primary analysis employed a weighted (two-sided) log-rank test with weight increasing linearly from zero at randomization to a maximum of one at 10 years and constant thereafter, to enhance statistical power under the design assumptions [18]. The time to benign proliferative breast disease was defined as the number of days from randomization to CaD to the first post-randomization diagnosis. For the present report, subjects who developed breast cancer (39 in the intervention group, 34 in the placebo group) or benign proliferative breast disease (61 intervention, 45 placebo) between initial randomization to an HT trial and/or the DM trial and subsequent randomization to the CaD trial were excluded from the analysis, leaving a total of 18,076 women in the intervention group and 18,027 in the placebo group. Follow-up time was censored at the date of last documented contact, diagnosis of breast cancer, mastectomy, or death, or trial close-out (which took place been October 2004 and March 2005), whichever occurred first. Women who developed a non-proliferative benign breast lesion continued to be followed up because they remained at risk of developing a subsequent proliferative lesion. Event rates over time were summarized using cumulative hazard plots. The intervention effect was summarized using hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) estimated from Cox proportional hazards models [19], with stratification by age, prior breast biopsies, and randomization to the WHI HT and DM trials. Interaction was investigated by including product terms between treatment assignment and indicator variables for the subsets of interest in Cox proportional hazards models stratified by age, prior breast biopsies, and randomization to the HT and DM trials, and was assessed by testing the equality of the product-term coefficients. The proportional hazards assumption, which was tested both by fitting models containing a product-term between the intervention and follow-up time and assessing the coefficient of the product-term for statistical significance, and by fitting piecewise constant intervention effects on non-overlapping time intervals and testing for equality of such terms with the intervals chosen in advance, was shown not to be violated. Annualized event rates were calculated for comparisons of absolute disease rates. Results were considered statistically significant when two-sided P-values were ≤0.05.

Results

The study groups differed little at baseline with respect to age, ethnicity, breast cancer risk factors, participation in other WHI trials, and intake of energy or selected nutrients and vitamins, including calcium and vitamin D (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women’s Health Initiative calcium plus vitamin D supplementation triala

| No. of participants (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation (n = 18,076) | Placebo (n = 18,027) | |

| Age, yearsb | 62.36 (6.96) | 62.35 (6.91) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 14,967 (82.80) | 15,036 (83.41) |

| Black | 1,671 (9.24) | 1,631 (9.05) |

| Hispanic | 783 (4.33) | 715 (3.97) |

| American Indian | 77 (0.43) | 72 (0.40) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 366 (2.02) | 347 (1.92) |

| Other | 178 (0.98) | 194 (1.08) |

| Unknown | 34 (0.19) | 32 (0.18) |

| Family history of breast cancer (%)c | 3,010 (16.65) | 2,984 (16.55) |

| Gail model 5-year risk ≥1.75 (%) | 5,850 (32.36) | 5,823 (32.30) |

| Body mass indexb,d | 29.13 (6.43) | 29.05 (6.25) |

| Prior breast disease | ||

| No | 131.06 (72.50) | 13,053 (72.41) |

| 1 biopsy | 2,343 (12.96) | 2,289 (12.70) |

| ≥2 biopsies | 858 (4.75) | 886 (4.91) |

| Unknown | 1,769 (9.79) | 1,799 (9.98) |

| Age (years) at menarche | ||

| ≤ 10 | 1,222 (6.76) | 1,239 (6.87) |

| 11–14 | 15,119 (83.64) | 14,941 (82.88) |

| ≥15 | 1,664 (9.21) | 1,790 (9.93) |

| Unknown | 71 (0.39) | 57 (0.32) |

| Age (years) at first full-term pregnancy | ||

| Never had term pregnancy | 399 (2.21) | 444 (2.46) |

| <;20 | 2,792 (15.45) | 2,667 (14.79) |

| 20–29 | 10,584 (58.55) | 10,717 (59.45) |

| ≥30 | 1,261 (6.98) | 1,197 (6.64) |

| Unknown | 3,040 (16.82) | 3,002 (16.65) |

| Parity | ||

| Never | 1,829 (10.12) | 1,894 (10.51) |

| 1 | 1,462 (8.09) | 1,459 (8.09) |

| 2 | 4,117 (22.78) | 4,013 (22.26) |

| 3 | 4,389 (24.28) | 4,382 (24.31) |

| 4+ | 6,190 (34.24) | 6,192 (34.35) |

| Unknown | 89 (0.49) | 87 (0.48) |

| Age (years) at natural menopauseb | 48.08 (6.42) | 48.00 (6.47) |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||

| Ever used (%) | 8,140 (45.03) | 8,194 (45.45) |

| Duration of use, yearsb | 5.42 (5.27) | 5.49 (5.28) |

| Postmenopausal hormone use | ||

| Estrogen alone | ||

| Ever used (%) | 5,969 (33.02) | 6,068 (33.66) |

| Duration of use, yearsb | 8.83 (8.46) | 8.99 (8.57) |

| Estrogen plus progestin | ||

| Ever used (%) | 4,204 (23.26) | 4,242 (23.53) |

| Duration of use, yearsb | 5.41 (4.98) | 5.41 (4.94) |

| Mammography screening within 2 years (%) | 13,899 (76.89) | 13,853 (76.85) |

| Enrolment in WHI estrogen alone trial (%) | ||

| No | 100,046 (55.58) | 10,017 (55.57) |

| Active | 1,524 (8.43) | 1,539 (8.54) |

| Control | 1,537 (8.50) | 1,556 (8.63) |

| Enrolment in WHI estrogen plus progestin trial (%) | ||

| No | 10,046 (55.58) | 10,017 (55.57) |

| Active | 2,498 (13.82) | 2,525 (14.01) |

| Control | 2,471 (13.67) | 2,390 (13.26) |

| Enrolment in WHI dietary modification trial (%) | ||

| No | 5,568 (30.80) | 5,475 (30.37) |

| Intervention | 4,740 (26.22) | 4,850 (26.90) |

| Control | 7,768 (42.97) | 7,702 (42.72) |

| Total daily energy intake, kcalb | 1,734.09 (751.45) | 1,737.56 (731.84) |

| Total daily fat intake, gb | 70.29 (37.46) | 70.38 (35.92) |

| Total daily calcium intake (supplements plus diet), mgb | 1,114.45 (683.90) | 1,114.52 (663.23) |

| Total daily vitamin D intake (supplements plus diet), mcgb | 344.24 (261.08) | 348.99 (259.65) |

Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding error

Mean (standard deviation)

First-degree female relative

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters

By the end of the follow-up period, of the women in the intervention group 352 had withdrawn, 144 had been lost to follow-up, and 744 had died; corresponding numbers for the control group were 332, 152, and 807, respectively. Adherence (defined as use of at least 80% of study medication), ranged from 60 to 63% during the first 3 years of follow-up, with an additional 13–21% taking at least half of their study pills. At study closeout, 76% were still taking the study pills, and 59% were taking at least 80% of the study medication.

During follow-up (average duration 6.8 years), we identified 2,548 potentially eligible biopsies that had been performed for benign breast disease. The eligibility of 48 biopsies could not be determined due to lack of consent, hospital refusal, and other reasons. Of the 2,500 biopsies confirmed to be eligible, consent was provided for review of 2,495, and histologic sections were obtained for 2,447 of these. Of the sections reviewed, 43 were found to be from biopsies that occurred before randomization and 175 showed no breast tissue and these 218 sections were excluded from further consideration. The 2,229 eligible sections that were reviewed were from 2,028 women. Of these women, 249 were excluded due to censoring (so that the corresponding section was excluded from consideration), 4 had no pathological diagnosis, 860 had a non-proliferative lesion, and 915 developed an incident benign proliferative lesion.

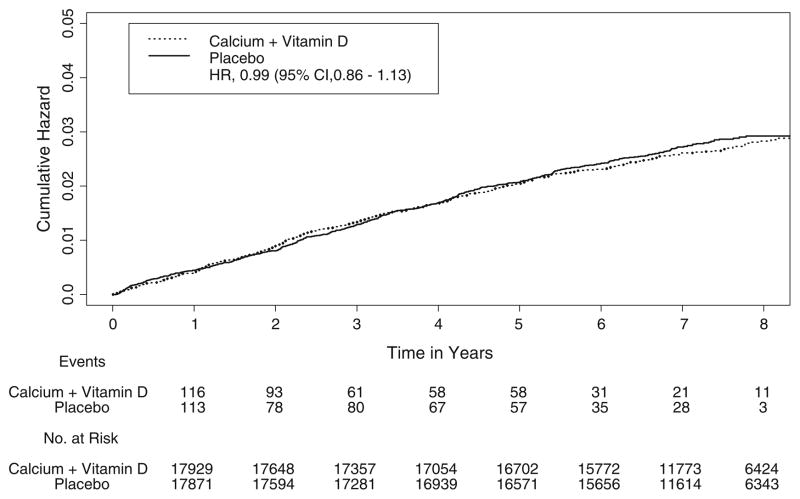

Overall, 915 incident cases of benign proliferative breast disease were ascertained, with 450 in the intervention group and 465 in the placebo group. CaD supplementation was not associated with altered risk of proliferative breast disease (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.86–1.13; Table 2), and there was no difference between the intervention and control groups with respect to the cumulative hazard of benign proliferative breast disease (all types combined) over time (Fig. 1). A slight, statistically non-significant decrease in risk was seen for those who had either proliferative disease with atypia or non-atypical proliferative breast disease that was at least moderate in extent (HR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.77–1.07), whereas risk of atypical hyperplasia alone was essentially unaltered by the intervention (HR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.74–1.46). The overall CaD supplementation effect was largely unchanged by exclusion of the first year of follow-up (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.85–1.14), exclusion of women with a breast biopsy prior to the commencement of the trial (HR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.81–1.12), or adjustment for use of prior menopausal HT (estrogen alone or estrogen plus progestin) (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.86–1.13).

Table 2.

Risk of benign proliferative breast disease (BPBD) in association with calcium plus vitamin D (CaD) supplementation, overall and by the presence/absence of atypia

| No. of cases (annualized %)

|

HR (95% CI)a |

P-value

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation (n = 18,076) | Placebo (n = 18,027) | Unweighted | Weightedb | ||

| BPBD, all | 450 (0.36) | 465 (0.38) | 0.99 (0.86, 1.13) | 0.83 | 0.34 |

| BPBD without atypia | 370 (0.30) | 383 (0.31) | 0.97 (0.84, 1.13) | 0.73 | 0.15 |

| BPBD without atypia (moderately extensive or florid) or with atypia | 307 (0.25) | 343 (0.28) | 0.91 (0.77, 1.07) | 0.26 | 0.10 |

| Atypical hyperplasia | 80 (0.06) | 82 (0.07) | 1.04 (0.74, 1.46) | 0.82 | 0.43 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Proportional hazards model stratified by age, prior breast biopsies, and treatment assignment in the HRT and DM trials

Weighted log-rank test stratified by age, prior breast disease, and treatment assignment in the HRT and DM trials. Weights increase linearly from zero at randomization to a maximum of one at 10 years

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of the cumulative hazard of benign proliferative breast disease in association with calcium plus vitamin D supplementation, as compared with placebo

Risk of benign proliferative breast disease in association with CaD supplementation varied little by baseline levels of dietary variables, or by levels of most of the demographic variables and breast cancer risk factors measured at baseline (Tables 3, 4). For those who were in the comparison group for the DM trial and were not in the active arm of either of the hormone trials, the HR in association with CaD supplementation was 1.04 (95% CI = 0.83–1.31). Although there was a statistically significant interaction between the intervention and age, the variation in risk was not monotonic, risk being highest in those who were 60–69 years old at baseline and lowest in those who were 70–79 years old (Table 4).

Table 3.

Risk of benign proliferative breast disease in association with calcium plus vitamin D supplementation, by intake of selected dietary variables at baseline

| No. cases of BPBD (annualized %)a

|

HR (95% CI) | P-value for interactionb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation (n = 18,076)− | Placebo (n = 18,027) | |||

| Energy intake, kcal | ||||

| <1392 | 136 (0.32) | 166 (0.40) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.07) | |

| 1,392 to <1664 | 85 (0.38) | 80 (0.37) | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) | 0.47 |

| 1,664 to <1959 | 86 (0.42) | 76 (0.37) | 1.11 (0.80, 1.54) | |

| ≥1959 | 141 (0.37) | 142 (0.38) | 1.05 (0.82, 1.34) | |

| Percentage of energy from fat, kcal | ||||

| <27.9 | 48 (0.34) | 48 (0.35) | 0.99 (0.65, 1.51) | |

| 27.9 to <32.3 | 66 (0.39) | 77 (0.45) | 0.82 (0.57, 1.16) | 0.70 |

| 32.3 to <36.8 | 153 (0.40) | 167 (0.43) | 1.00 (0.79, 1.25) | |

| ≥36.8 | 181 (0.34) | 172 (0.33) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) | |

| Total fat intake, g | ||||

| <46.2 | 107 (0.34) | 112 (0.37) | 0.99 (0.75, 1.31) | |

| 46.2 to <59.8 | 80 (0.33) | 93 (0.40) | 0.78 (0.57, 1.07) | 0.33 |

| 59.8 to <76.0 | 107(0.43) | 99 (0.39) | 1.16 (0.87, 1.54) | |

| ≥76.0 | 154 (0.36) | 160 (0.37) | 1.00 (0.79, 1.27) | |

| Vegetable and fruit, servings/day | ||||

| <2.3 | 101 (0.33) | 105 (0.35) | 0.95 (0.71, 1.27) | |

| 2.3 to <3.3 | 117 (0.40) | 117 (0.42) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.32) | 0.62 |

| 3.3 to <4.6 | 93 (0.32) | 112 (0.38) | 0.86 (0.64, 1.14) | |

| ≥4.6 | 137 (0.40) | 130 (0.38) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.42) | |

| Grains, servings/day | ||||

| <3 | 108 (0.33) | 126 (0.39) | 0.90 (0.69, 1.19) | |

| 3 to <4.3 | 113 (0.36) | 116 (0.38) | 0.96 (0.73, 1.25) | 0.79 |

| 4.3 to <5.9 | 107 (0.37) | 106 (0.36) | 0.99 (0.75, 1.31) | |

| ≥5.9 | 122 (0.40) | 117 (0.39) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.44) | |

| Total daily calcium intake (supplements plus diet), mg | ||||

| <633.0 | 102 (0.33) | 109 (0.36) | 0.94 (0.70, 1.25) | |

| 633.0 to <978.4 | 109 (0.35) | 132 (0.43) | 0.88 (0.67, 1.15) | 0.64 |

| 978.4 to <1449.2 | 113 (0.37) | 94 (0.31) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.50) | |

| ≥1449.2 | 124 (0.41) | 129 (0.42) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.31) | |

| Total daily vitamin D intake (supplements plus diet), mcg | ||||

| <130.2 | 106 (0.33) | 102 (0.34) | 0.97 (0.72, 1.30) | |

| 130.2 to <265.8 | 120 (0.39) | 117 (0.38) | 1.09 (0.83, 1.42) | 0.73 |

| 265.8 to <531.6 | 116 (0.38) | 130 (0.43) | 0.88 (0.68, 1.14) | |

| ≥531.6 | 106 (0.36) | 115 (0.37) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.33) | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

For some variables, the number of events does not equal the total number shown in Table 2 due to missing values

Unweighted proportional hazards model stratified by age, prior disease, and randomization group

Table 4.

Risk of benign proliferative breast disease in association with calcium plus vitamin D supplementation, by selected baseline characteristics

| No. cases of BPBD (annualized %)b

|

HR (95% CI) | P-value for interactiona | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation (n = 18,076) | Placebo (n = 18,027) | |||

| Age, years | ||||

| 50–59 | 175 (0.36) | 206 (0.44) | 0.88 (0.71, 1.09) | |

| 60–69 | 224 (0.41) | 194 (0.35) | 1.20 (0.98, 1.46) | 0.02 |

| 70–79 | 51 (0.25) | 65 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.47, 1.02) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 385 (0.38) | 401 (0.39) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.14) | |

| Black | 34 (0.30) | 29 (0.26) | 1.29 (0.76, 2.19) | 0.21 |

| Hispanic | 13 (0.25) | 19 (0.40) | 0.51 (0.25, 1.07) | |

| Other | 17 (0.42) | 13 (0.32) | 1.31 (0.62, 2.76) | |

| Region according to solar irradiance, Ly | ||||

| 300–325 | 141 (0.38) | 153 (0.41) | 0.94 (0.73, 1.20) | |

| 350 | 102 (0.39) | 115 (0.44) | 0.93 (0.70, 1.23) | 0.86 |

| 375–380 | 49 (0.36) | 44 (0.32) | 1.21 (0.78, 1.88) | |

| 400–430 | 72 (0.34) | 72 (0.35) | 0.98 (0.69, 1.37) | |

| 475–500 | 86 (0.34) | 81 (0.32) | 1.04 (0.76, 1.43) | |

| Family history of breast cancer in first-degree relative | ||||

| No | 346 (0.36) | 358 (0.37) | 0.97 (0.83, 1.14) | 0.33 |

| Yes | 90 (0.44) | 80 (0.40) | 1.16 (0.85, 1.58) | |

| Gail model 5-year risk, % | ||||

| <1.25 | 136 (0.31) | 155 (0.35) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | |

| 1.25–1.74 | 146 (0.36) | 154 (0.38) | 0.90 (0.71, 1.14) | 0.48 |

| ≥1.75 | 168 (0.43) | 156 (0.40) | 1.10 (0.87, 1.38) | |

| Body mass indexc | ||||

| <25 | 131 (0.40) | 142 (0.42) | 1.00 (0.78, 1.29) | |

| 25–29 | 165 (0.37) | 157 (0.36) | 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) | 0.84 |

| 30–34 | 87 (0.31) | 100 (0.37) | 0.87 (0.65, 1.18) | |

| ≥35 | 67 (0.37) | 66 (0.37) | 1.05 (0.74, 1.50) | |

| Age at menarche, years | ||||

| ≤ 10 | 23 (0.27) | 34 (0.41) | 0.69 (0.40, 1.20) | |

| 11–14 | 392 (0.38) | 377 (0.37) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.21) | 0.20 |

| ≥15 | 35 (0.31) | 51 (0.42) | 0.77 (0.49, 1.24) | |

| Age at first full-term pregnancy | ||||

| Never had term | 12 (0.44) | 16 (0.53) | 0.86 (0.39, 1.88) | |

| <20 | 64 (0.34) | 70 (0.39) | 0.94 (0.65, 1.34) | 0.25 |

| 20–29 | 270 (0.37) | 287 (0.39) | 0.96 (0.80, 1.14) | |

| ≥30 | 40 (0.47) | 28 (0.35) | 1.67 (0.98, 2.84) | |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 43 (0.34) | 50 (0.39) | 0.81 (0.53, 1.23) | |

| 1 | 45 (0.46) | 35 (0.35) | 1.46 (0.92, 2.31) | |

| 2 | 113 (0.40) | 119 (0.44) | 0.96 (0.73, 1.26) | 0.40 |

| 3 | 104 (0.34) | 104 (0.35) | 1.06 (0.79, 1.41) | |

| ≥4 | 145 (0.35) | 154 (0.37) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.18) | |

| Age at natural menopause | ||||

| <48 | 172 (0.39) | 163 (0.37) | 1.11 (0.89, 1.39) | |

| 48 to <50 | 39 (0.35) | 44 (0.39) | 0.86 (0.55, 1.35) | 0.63 |

| 50 to <53 | 117 (0.36) | 130 (0.40) | 0.91 (0.71, 1.19) | |

| ≥53 | 102 (0.41) | 94 (0.38) | 1.02 (0.76, 1.36) | |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||||

| None | 209 (0.31) | 226 (0.34) | 0.94 (0.77, 1.14) | |

| <5 | 125 (0.41) | 124 (0.41) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.33) | 0.78 |

| ≥5 | 116 (0.45) | 115 (0.43) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.37) | |

| Baseline postmenopausal hormone use, years | ||||

| Estrogen alone | ||||

| None | 272 (0.33) | 287 (0.35) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.12) | |

| <5 | 74 (0.42) | 68 (0.40) | 1.22 (0.86, 1.74) | 0.43 |

| ≥5 | 104 (0.45) | 110 (0.46) | 0.97 (0.74, 1.29) | |

| Estrogen plus progestin, years | ||||

| None | 300 (0.32) | 324 (0.35) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.12) | |

| <5 | 62 (0.38) | 73 (0.46) | 0.87 (0.61, 1.25) | 0.25 |

| ≥5 | 88 (0.69) | 68 (0.52) | 1.26 (0.91, 1.76) | |

| Enrolment in WHI HRT trial | ||||

| Estrogen alone | ||||

| No | 267 (0.39) | 290 (0.42) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.15) | |

| Active | 52 (0.51) | 42 (0.41) | 1.23 (0.80, 1.90) | 0.59 |

| Placebo | 23 (0.22) | 23 (0.22) | 1.00 (0.54, 1.83) | |

| Estrogen plus progestin, years | ||||

| No | 267 (0.39) | 290 (0.42) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.15) | |

| Active | 69 (0.41) | 66 (0.39) | 1.11 (0.77, 1.59) | 0.45 |

| Placebo | 39 (0.23) | 44 (0.27) | 0.76 (0.49, 1.19) | |

| Enrolment in WHI DM trial | ||||

| No | 113 (0.30) | 120 (0.33) | 0.94 (0.72, 1.23) | |

| Intervention | 132 (0.40) | 152 (0.46) | 0.90 (0.71, 1.15) | 0.50 |

| Placebo | 205 (0.38) | 193 (0.37) | 1.08 (0.88, 1.33) | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Unweighted proportional hazards model stratified by age, prior disease, and randomization group

For some variables, the number of events does not equal the total number shown in Table 2 due to missing values

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters

On study personal use of vitamin D (and calcium) was allowed, initially up to 600 IU of vitamin D daily, but subsequently this limit was increased to 1,000 IU daily. Use of non-protocol calcium and vitamin D supplement use during the trial was similar in the two randomization groups. At year six, 52.0% of the intervention group and 52.8% of the placebo group reported use of at least 400 IU daily of non-protocol vitamin D supplements; calcium intake increased by ~100 mg daily in both groups during follow-up. When personal use of calcium supplements was adjusted for as a time-dependent covariate, the estimate of the effect of the intervention on risk of benign proliferative breast disease overall was essentially unchanged (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.88–1.16).

To address the possible impact of non-adherence on the study results, we employed the inverse probability-weighting scheme in order to estimate a ‘‘full adherence’’ HR function for the intervention [20]. A full adherence HR was estimated with inverse probability of censoring-weighted estimators with adjustment for 17 covariates thought to be likely to influence adherence. For this analysis, non-adherence was defined as an adherence rate of <80%. This yielded a HR of 0.96 (95% CI = 0.83–1.12) for all benign proliferative breast disease combined. An almost identical result was obtained when non-adherence was defined as an adherence rate of <50% (HR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.84–1.11). In further analyses designed to address the possible impact of non-adherence, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by censoring follow-up on participants 6 months after their rate of adherence to the study medication dropped below 50%. This did not change the findings (HR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.87–1.17). Similarly, censoring follow-up 6 months after adherence dropped below 80% also demonstrated absence of an association (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.84–1.17).

As indicated earlier, participants had regular mammograms and clinical breast exams. There was no difference between the intervention and control group with respect to the frequency with which these were performed. After adjustment for the frequency of mammograms, the effect of intervention was essentially unchanged (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.86–1.13). It was also unchanged after adjustment for the mammogram results (‘‘suspicious abnormality—biopsy should be considered’’ or ‘‘highly suggestive of malignancy’’ versus less severe categories) (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.86–1.13). Furthermore, neither adjustment for the frequency of clinical breast exams (HR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.86–1.13) nor adjustment for the clinical breast exam results (HR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.86–1.13) changed the estimated CaD supplementation effect.

Discussion

In the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial reported here, daily supplementation with 1,000 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate plus 400 IU of vitamin D3 for an average of almost 7 years was not associated with altered risk of benign proliferative breast disease, either overall or when examined by histologic subcategory. Risk did vary significantly (but non-monotonically) by age at baseline, but many such associations were examined and this observation may represent a chance finding. Given that calcium and vitamin D were administered jointly, it was not possible to examine their effects separately.

In experimental studies, both calcium and vitamin D have been shown to exert anti-proliferative, pro- differentiating, and pro-apoptotic effects on mammary epithelial cells [3, 21–23], thereby rendering protective effects of these supplements against the risk of developing benign proliferative breast lesions, and of breast cancer, biologically plausible. However, epidemiologic evidence bearing on the association between calcium, vitamin D, and risk of benign proliferative breast disease is somewhat limited. There are some observational data supporting an inverse association between dietary calcium intake and risk of benign proliferative breast disease [24] and of all types of benign breast disease combined [25], but none concerning the association between vitamin D intake and risk. Furthermore, we are not aware of any previous randomized trials that have addressed these associations. With respect to breast cancer, the available data are somewhat conflicting. Although the results of observational epidemiologic studies are suggestive of an inverse association with calcium intake, most studies of dietary vitamin D intake and breast cancer risk have not shown associations [3, 26, 27]. Two randomized trials have evaluated the association between CaD supplementation and breast cancer risk. In the same WHI trial that was used for the present study, there was no association between CaD supplementation and breast cancer risk [28], whereas a recent small, randomized trial that was designed primarily to test the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk and used substantially larger doses than those used in WHI (1,400 mg/day of calcium citrate or 1,500 mg/day of calcium carbonate alone or with 1,000 IU/day of vitamin D3) showed fewer total cancer cases and breast cancer cases in the intervention groups than in the placebo group [29].

At baseline in the WHI CaD trial, the mean total vitamin D intake was about 365 IU/day and the mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the major circulating form of vitamin D, was about 42 nmol/l [30]. It has been shown that 25(OH)D concentrations in older adults can be increased by about 10–40 nmol/l to means of about 60 nmol/l with an intake of 400 IU vitamin D/day [31]. Therefore, although the supplementation dose administered in this trial potentially increased 25(OH)D levels substantially, it may have been insufficient to attain the level (≥75 nmol/l) currently considered to be necessary for the prevention of cancer (and other outcomes) [32]. With respect to calcium, mean baseline total intake was about 1,115 mg/day in both randomization groups, which may have been too high to allow demonstration of an effect of supplementation.

Strengths of the present study include its randomized design, the large, diverse study population, comprehensive breast cancer risk factor assessment, regular mammo-graphic and clinical breast exams, and centralized review of histologic sections. However, in addition to concerns about baseline intake and the administered dose of supplements, the trial had a number of potential limitations that may have compromised its ability to demonstrate an effect [9, 30]. Specifically, non-protocol use of calcium and vitamin D was allowed; the intervention may have been initiated too late in life; the duration of the intervention may have been insufficient; and, as designed, the trial did not allow the effects of calcium and vitamin D to be examined separately. Additionally, differential ascertainment of the outcome in the two randomization groups may have occurred, although this seems unlikely given that compliance with the annual or biennial mammograms and clinical breast exams was high and essentially the same in both groups (under-ascertainment in both groups is a possibility given that breast biopsies were not performed on all study subjects), and any misclassification of the outcome is likely to have been non-differential and therefore to have biased the effect estimate for CaD supplementation towards the null [33].

In conclusion, the results of the present trial suggest that daily administration of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D3 for about 7 years does not alter the risk of benign proliferative breast disease. Further studies employing higher doses of vitamin D in particular may be informative.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the WHI investigators and staff, and the WHI participants, for their outstanding dedication and commitment.

Funding The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The present study was supported by National Cancer Institute RO1 CA 077290-07.

Appendix

A list of key investigators involved in this research follows. A full listing of WHI investigators can be found at the following website: http://www.whi.org

Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Elizabeth Nabel, Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Linda Pottern, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller.

Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA)

Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Charles L. Kooperberg, Ruth E. Patterson, Anne McTiernan; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker; (Medical Research Labs, Highland Heights, KY) Evan Stein; (University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) Steven Cummings.

Clinical Centers: (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY)

Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) Jennifer Hays; (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn Manson; (Brown University, Providence, RI) Annlouise R. Assaf; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) Lawrence Phillips; (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Shirley Beresford; (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC) Judith Hsia; (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA) Rowan Chlebowski; (Kaiser Per-manente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR) Evelyn Whitlock; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA) Bette Caan; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) Jane Morley Kotchen; (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL) Linda Van Horn; (Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL) Henry Black; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY) Dorothy Lane; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) Cora E. Lewis; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Tamsen Bassford; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) John Robbins; (University of California at Irvine, CA) F. Allan Hubbell; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA) Howard Judd; (University of California at San Diego, La-Jolla/Chula Vista, CA) Robert D. Langer; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) Margery Gass; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI) David Curb; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA) Judith Ockene; (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ) Norman Lasser; (University of Miami, Miami, FL) Mary Jo O’Sullivan; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Karen Margolis; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) Gerardo Heiss; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN) Karen C. John-son; (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) Robert Brzyski; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) Gloria E. Sarto; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Denise Bonds; (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI) Susan Hendrix.

Contributor Information

Thomas E. Rohan, Email: rohan@aecom.yu.edu, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

Abdissa Negassa, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

Rowan T. Chlebowski, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA

Clementina D. Ceria-Ulep, School of Nursing and Dental Hygiene, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA

Barbara B. Cochrane, School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Dorothy S. Lane, Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, SUNY at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY, USA

Mindy Ginsberg, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

David L. Page, Vanderbilt University Medical School, Nashville, TN, USA

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Fernández LMG. Use of statistics to assess the global burden of breast cancer. Breast J. 2006;12(Suppl 1):S70–S80. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen WY, Rosner B, Colditz GA. Moving forward with breast cancer prevention. Cancer. 2007;109:2387–2391. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22711. 10.1002/ cncr.22711 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui Y, Rohan TE. Vitamin D, calcium, and breast cancer risk: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1427–1437. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohan TE, Henson DE, Franco EL, Albores-Saavedra J. Cancer precursors. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr, editors. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang DY, Fentiman IS. Epidemiology and endocrinology of benign breast disease. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1985;6:5–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01806008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakhani SR. The transition from hyperplasia to invasive carcinoma of the breast. J Pathol. 1999;187:272–278. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199902)187:3<272::AID-PATH265>3.0.CO;2-2. 10.1002/ (SICI)1096-9896(199902)187:3<272::AID-PATH265>3.0.CO; 2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:275–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Cauley JA, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative calcium–vitamin D trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(Suppl):S98–S106. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colo-rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:684–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. 10.1056/NEJM oa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, et al. Implementation of the Women’s Health Initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(Suppl):S5–S17. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(Suppl):S18–S77. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritenbaugh C, Patterson RE, Chlebowski RT, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative dietary modification trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(Suppl):S87–S97. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR. The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(Suppl):S78–S86. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00045-0. 10.1016/S1047-2797 (03)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page DL, Rogers LW. Combined histologic and cytologic criteria for the diagnosis of mammary atypical ductal hyper-plasia. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:1095–1097. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90026-y. 10.1016/0046-8177(92) 90026-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Jensen RA, Plummer WD, Jr, Simpson JF. Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361:125–129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentice RL, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of invasive breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295:629–642. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for non-compliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS clinical trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (PCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–781. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duchen MR. Mitochondria and calcium: from cell signalling to cell death. J Physiol. 2000;529:57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawata H, Lamiakito T, Takayashiki N, Tanaka A. Vitamin D3 suppresses the androgen-stimulated growth of mouse mammary carcinoma SC-3 cells by transcriptional repression of fibroblast growth factor 8. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:793–799. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lips P. Vitamin D physiology. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohan TE, Jain M, Miller AB. A case-cohort study of diet and risk of benign proliferative epithelial disorders of the breast (Canada) Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:19–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1008841118358. 10.1023/A:1008 841118358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galvan-Portillo M, Torres-Sanchez L, Lopez-Carrillo L. Dietary and reproductive factors associated with benign breast disease in Mexican women. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43:133–140. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC432_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robien K, Cutler GJ, Lazovich D. Vitamin D intake and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:775–782. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9020-x. 10.1007/ s10552-007-9020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin J, Manson J, Lee I-M, Cook NR, Buring JE, Zhang SM. Intakes of calcium and vitamin D and breast cancer risk in women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1050–1059. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1050. 10.1001/archinte. 167.10.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chlebowski RT, Johnson KC, Kooperberg C, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn360. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wactawski-Wende J, Anderson GL, O’Sullivan MJ. Calcium plus vitamin D and the risk of colorectal cancer. The authors reply. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2288. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. 10.1056/NEJM oa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:18–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vieth R, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Boucher BJ, et al. The urgent need to recommend an intake of vitamin D that is effective. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:649–650. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. Little Brown; Boston: 1986. p. 106. [Google Scholar]