Abstract

When an existing standard marker does not have sufficient classification accuracy on its own, new markers are sought with the goal of yielding a combination with better performance. The primary criterion for selecting new markers is that they have good performance on their own and preferably be uncorrelated with the standard. Most often linear combinations are considered. In this paper we investigate the increment in performance that is possible by combining a novel continuous marker with a moderately performing standard continuous marker under a variety of biologically motivated models for their joint distribution. We find that an uncorrelated continuous marker with moderate performance on its own usually yields only minimally improved performance. We identify other settings that lead to large improvements, including a novel marker that has very poor performance on its own but is highly correlated with the standard and a novel marker with poor to moderate performance that is highly correlated with the standard but only in one class category. These results suggest changing current strategies for identifying markers to be included in panels for possible combination. Using simulated and real datasets we examine the merits of a broadened strategy that selects panels of markers as candidates based on their joint performance with existing markers, compared with the standard strategy that selects markers based on their marginal performance. We find that a broadened strategy can be fruitful but necessitates using studies with large numbers of subjects.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Marker combination, Incremental Value, ROC curve, Sensitivity, Specificity

1. Background

Biomarkers and clinical predictors are sought to assist in disease screening, in diagnosis and in making prognostic assessments for patients after diagnosis. This is an active area of research that has met with mixed success. In cancer research in particular, many biomarkers have been discovered but none, on its own, has yet been shown to have adequate performance for use in clinical practice. Efforts are currently underway to assemble panels of markers with the goal of developing marker combinations that have better performance.

We have previously investigated statistical characteristics of a single biomarker that lead to accurate classification or prediction of outcomes for individuals [1]. We and others have shown that the marker must be very strongly associated with outcome, having an odds ratio much larger than is typically observed in epidemiologic studies of association. This observation has been useful in setting targets and expectations for the performance of single biomarkers. In this paper, we turn our attention to the setting where the performance of the best-performing marker is still inadequate, and we seek to combine other markers with it. We ask what statistical characteristics of an additional marker lead to substantially improved performance. This might help develop strategies for assembling panels of markers for evaluation in rigorous validation studies.

As an example we consider CA-125, which is a biomarker for ovarian cancer. For early detection of ovarian cancer, CA-125 was recently shown to have the best performance among a panel of 6 markers studied [2]. Yet its performance is far from adequate for population screening. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) is approximately 0.7 for detecting ovarian cancer 2 years prior to symptomatic clinical diagnosis. Moreover, using a threshold that sets the false positive rate (FPR) at 0.05, approximately 18% of cancers can be detected early with CA-125, i.e. the true positive rate (TPR) is only 0.18. Can we expect that combining other markers with CA-125 will improve performance substantially for screening? How should we identify markers for combining with CA-125?

A common intuitively appealing strategy for selecting novel markers to combine with each other and with existing markers is to identify those with good performance on their own. One may prioritize those with low correlation since they apparently provide independent information. Moreover, in practice linear marker combinations are often studied. For example, Gail [3] examined the potential improvement of the performance of standard clinical factors for predicting breast cancer that could be gained by adding seven SNPs with good performance on their own, assuming statistical independence with standard risk factors and using a linear logistic model for combination. He found that the area under the ROC curve increased only slightly from 0.607 to 0.632. As another example, Anderson et al. [2] recently studied a panel of 6 ovarian cancer markers. Markers were selected for inclusion in this panel if they had high ranking performance on their own and combinations were studied primarily using linear algorithms.

In the first part of this paper we quantify the potential gain in classification performance that can be achieved by combining markers assuming various classic statistical and biologically motivated models for their joint distributions. We also note the function for combining them optimally and compare with the linear combination function. Practical implications of our results are discussed in the second part of this paper. In particular, we show that a broader approach to selecting panels of markers than the current popular approach may lead to better marker combinations but will require large sample sizes in order to be fruitful.

2. Marker Distributions and Combinations

2.1. Methods

We study marker combinations for classifying subjects according to true outcome status D, with D = 1 denoting a case and D = 0 a control. We use a variety of statistical models for the joint distributions of markers and quantify what can possibly be achieved by combining them. Our calculations are done for the models themselves, not for estimates based on a sample of data. Sampling variability in real data adds another layer of complexity that we address later. For simplicity and to gain insights we focus on combining two markers. One of the markers, that we call the standard or baseline marker X, has specified performance on its own. We consider another marker that we call the novel marker Y, vary the performance of Y relative to X, and determine to what extent the performance of the combination (X, Y) is improved relative to X alone. The sensitivity (TPR) and specificity (1-FPR) and the ROC curve, which is a plot of TPR versus FPR, are used to quantify classification performance.

Long established statistical theory [4, 5] has shown that the optimal combination of (X, Y) is obtained by calculating the risk score function of X and Y, defined as r(X, Y) = P(D = 1|X, Y), and setting criteria for positivity as

In other words, the ROC curve for r(X, Y) is higher and further to the left than the ROC curve for any other combination of (X, Y). Therefore, we calculate the optimal combination function, r(X, Y), for each model and compare ROC values for r(X, Y) with corresponding ROC values for X in order to quantify the improvement in performance gained by combining Y with X.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Bivariate Binormal Equal Correlation Markers

The bivariate binormal model is a classic statistical model for two diagnostic tests or markers [6]. It assumes that the markers, (X, Y), have a bivariate normal distribution in cases and controls. Although we focus on normal models, note that the results apply much more generally to markers that are normal after some unspecified monotone transformations, since the ROC curve is unchanged by such transformations of the data [7]. We further assume here that case and control distributions have the same covariance matrix, where ρ represents the correlation between X and Y in cases and in controls. Without losing generality, in controls the markers have means 0 and standard deviations 1 since we can always standardize the markers using the control distribution. We write

| (1) |

and

The ROC curve for X alone is binormal with intercept μX and slope 1

because X ~ N(0, 1) in controls and X ~ N(μX, 1) in cases (Pepe, 2003). The AUC for X is

With μX = 0.742, we have AUCX = 0.7 and ROCX(0.05) = 0.183, implying that using a threshold that corresponds to FPR = 5%, the test detects 18.3% of the cases. This reflects the approximate performance of CA-125 for detecting ovarian cancer 2 years before clinical symptoms.

The ROC curve and AUC for Y alone take the same forms as those for X, but with μY replacing μX. Values of μY in the range 0 to 0.742 were considered as they correspond to performance ranging between that of a useless marker (AUC = 0.5; ROC(0.05) = 0.05) and that of the standard marker X(AUC = 0.7; ROC(0.05) = 0.183).

For the bivariate binormal model with equal correlation, it is well known that

where α1 = (μX − ρμY)/(1 − ρ2), α2 = (μY − ρμX)/(1 − ρ2), and expit(W) = exp(W)/{1+exp(W)}. The combination of X and Y with optimal ROC curve is therefore W = α1X + α2Y, noting that the ROC curve for expit(W) is the same as that for W because expit is a monotone increasing function. Since a linear combination of normal variables is normally distributed, it follows that the best combination has a binormal ROC curve

and

When ρ = 0, the expressions simplify to

and

Therefore, when ρ = 0, larger values of μY lead to higher ROC values for the combination. In other words, if a marker is uncorrelated with X, its marginal performance determines the performance of the combination — markers that perform better on their own lead to better performing combinations. This is not surprising. However, the magnitude of improvement in performance is surprisingly small (Figure 1(a)). Fixing the FPR at 0.05, we see that when the AUC for Y is 0.6, only 2.3% more cases are detected, i.e. ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.206 versus ROCX(0.05) = 0.183. When Y on its own performs as well as X, (AUCY = 0.7), only 9.3% more cases are detected, i.e. ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.276 versus ROCX(0.05) = 0.183. See Web Figure A 1 for plots analogous to those in Figure 1, pertaining to AUCX,Y rather than ROCX,Y(0.05) as the measure of combination performance.

Figure 1. Bivariate binormal markers.

Detection of cases by the combination (X,Y) at the threshold that leads to FPR = 5%. The baseline marker X alone detects 18% of cases (AUCX = 0.7) and is indicated by a black dashed line. Shown are settings where (a) the correlation between markers in both cases and controls is 0, (b) the correlation is equal in cases and controls with positive coefficient ρ, and (c) the markers have a different correlation in controls and in cases, with correlation coefficients ρd̄ and ρD, respectively. See Web Figure A.1 for analogous plots pertaining to AUCX,Y as the measure of combination performance.

Figure 1(b) pertains to markers that may be correlated with X, ρ > 0. Interestingly, a positive correlation leads to a U-shaped curve for performance of the combination as a function of the marginal performance of Y (left panel). The inflection point occurs at , i.e. μY = ρμX, where the coefficient α2 for Y is equal to 0 and the optimal combination is determined to be X alone. From the right panel of Figure 1(b), we see that for markers with performance as good as X, i.e. AUCY = 0.7, performance improvement is maximized when ρ = 0 and decreases to no improvement when ρ = 1. In the latter setting, Y provides the same information as X so it adds nothing over X alone. Interestingly, however, for markers that are poor performers on their own (AUCY < 0.7), the existence of a correlation with X in cases and in controls yields a combination with improved performance. In the extreme, when AUCY = 0.5 and ρ = 1, the combination is a perfect marker. Classification rules for the optimal marker combination are shown in Figure 2(a) for some specific values of AUCY and ρ.

Figure 2.

Decision boundaries that separate positive and negative classifications based on (X,Y) when ROCY (0.05) = 0.100 (or equivalently when AUCX,Y = 0.6 for (a) and (b)). The FPR = 5% and FPR = 10% boundaries are shown with solid and dashed curves, respectively. Both the optimal and linear boundaries are shown. The solid points represent cases, while the hollow circles represent controls. Shown are settings where (a) the correlation between markers is equal in cases and controls, (b) the markers have a different correlation in controls and in cases, with correlation coefficients ρD̄ (set to 0) and ρD, respectively, and (c) the markers have a mixture bivariate binormal distribution in cases, with X and Y being discriminatory in proportions pX and pY of cases, respectively. We set pY = 0.4 and pX = 0.15, 0.4. See Web Figure A.2 for more examples.

The fact that poorly performing but highly correlated markers can add substantially to marker performance is an intriguing observation that mirrors the results of Guyon & Elisseeff [8] in the machine learning literature. Some intuition is gained by considering the case where Y is completely useless on its own, AUCY = 0.5. We compare the extreme scenarios of ρ = 0 (Y is completely independent of X in cases and controls) and ρ = 0.9 (Y is very strongly correlated with X in cases and controls). Figure 3 shows the FPR = 5% decision boundary for the optimal (X, Y) combination, as well as decision boundaries using each marker alone. We also include densities of X and Y conditional on disease. Y is a useless marker with overlapping case and control densities and not surprisingly, the horizontal decision rule based on it has TPR = 5% for FPR = 5%. X has slightly better performance, but there is still considerable overlap between its case and control densities. The vertical decision rule based on X alone has a TPR of only 18% for FPR = 5%. When ρ = 0 (left panel), the optimal (X, Y) combination assigns a weight of 0 to Y. That is, Y does not improve classification performance and the optimal combination performance is the same as that from X alone (TPR = 18% for FPR = 5%). The right panel shows that keeping the marginal performance of X and Y the same and simply increasing ρ to 0.9 can have a major effect. Combining Y with X adds a two-dimensional component to the decision rule that allows for much better separation of cases and controls, resulting in a significantly higher TPR of 53%.

Figure 3. Bivariate binormal equal correlation markers.

For AUCY = 0.5 and ρ = 0, 0.9, comparison of decision rules in detecting cases when FPR = 5%. Shown here is the decision rule based on the optimal (X,Y) combination (solid black line), and on X and Y alone. The solid points represent cases, while the hollow circles represent controls. The case density of each marker is represented with a solid curve, and the control density with a dashed curve.

We provide further intuition about this result by pointing out that such phenomena can arise in several practical settings. Consider that a measurement X made from a biological sample may be comprised of two biologic components, X = W+Y. If the component W is an excellent marker that cannot be measured and Y is a component that is unrelated to disease, then Y is a useless marker on its own, but in combination with X it yields W, the excellent marker. For example, the biomarker prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is made up of free and bound PSA components. As another example, consider the setting where Y is a baseline measurement of a biomarker, X is the current value and W is the change in the marker from baseline to present. If the change in the marker is strongly associated with occurrence of disease, the current measure X along with a possibly uninformative baseline value Y yields the change, W, which is an excellent marker. As examples, it has been hypothesized that the change in CA-125 and in PSA may be more informative of ovarian cancer and prostate cancer, respectively, than values measured at one point in time [9, 10, 11, 12, 13].

2.2.2. Bivariate Binormal Unequal Correlation Markers

Two markers may have a different correlation in cases than in controls. For example, there may be a high correlation in cases but a low correlation in controls. This would occur if both markers are at higher levels in cases with more extensive disease and at lower levels in cases with less extensive disease, a likely scenario for many markers. Markers of cell growth and inflammation fit this sort of scenario. For this setting we consider the following general joint model:

| (2) |

and

where subscripts D̄ and D are used for controls and for cases, respectively. The optimal marker combination no longer contains only linear terms in X and Y when ρD ≠ ρD̄. The risk function r(X, Y) can be shown to be a monotone function of .

Figure 2(b) shows marker values classified as positive and negative using this optimal combination that contains non-linear terms, for different values of ρD, assuming ρD̄ = 0. We see that discordance of marker values leads to negative classification while concordance leads to positive classification for disease. That is, if one marker is high but is not confirmed by a high value for the other marker, the subject is unlikely to be classified as a case. The result makes sense intuitively for this model.

Figure 1(c) shows the increment in performance gained by combining Y with X when the correlation is unequal between cases and controls. These calculations were made using numerical methods with a large simulated dataset since an analytic formula for ROCX,Y(f) was not feasible in this setting. In the left panel corresponding to the special setting where ρD̄ = 0 and ρD > 0, we see that better marginal performance of Y always leads to better performance for the combination (X, Y) and that stronger correlation of the markers in cases leads to better performance. Much larger gains in performance are possible when Y is correlated with X in cases (ρD > 0) compared with when ρD = 0, the setting shown in Figure 1(a). For example, if AUCY = 0.7 and it is uncorrelated with X in cases (Figure 1(a)), the combination can detect only 9.3% more cases than X alone (ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.276 versus ROCX(0.05) = 0.183). However, from the left panel of Figure 1(c) we see that it can detect 17% more cases (ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.349) when ρD = 0.6 and 22% (ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.400) when ρD = 0.8. Moreover, observe that even when Y is not useful on its own (AUCY = 0.5), it can greatly improve the performance of X if it is correlated with X only in cases.

When markers have a positive correlation in controls, we see from the right two panels of Figure 1(c) that the performance of (X, Y) combined is a U-shaped function of ρD. Better performance occurs when ρD and ρD̄ are very different. This also leads to the somewhat unintuitive result that when markers are highly correlated in controls, ρD̄ = 0.9, worse marginal performance of Y leads to better performance of the combination.

We noted earlier that the optimal marker combination no longer contains only linear terms in X and Y when marker correlations in cases and controls are unequal, resulting in a non-linear decision rule (Figure 2(b)). However, it is common practice to use the coefficients from a logistic model containing only linear terms in X and Y to obtain a combination of the form α̂1X + α̂2Y, which results in a linear decision rule. Figure 2(b) shows marker values classified as positive and negative at FPR = 5% and FPR = 10%, using such linear combinations derived from the logistic likelihood. We see that the structure imposed by unequal correlation in cases and controls implies that linear decision boundaries do not approximate very well the non-linear optimal boundaries. Figure 4 compares the combinations with respect to TPR when FPR is set equal to 5%. We see from the right two panels that a combination with only linear terms has performance comparable with the optimal combination for AUCY ≥ 0.6 when ρD < 0.5, but for ρD > 0.5 it has relatively poor discriminatory ability. Interestingly, when AUCY = 0.5, a model containing only linear terms in X and Y performs even worse than X alone. We also find that when an interaction term is added to the model, performance is often improved significantly, but is not comparable with the optimal combination when correlation between X and Y is high in cases but zero in controls.

Figure 4. Bivariate binormal unequal correlation markers.

Comparison of decision rules in detecting cases when FPR = 5%. Shown here are (X,Y) combinations using the optimal risk score, a logistic model with linear terms and a logistic model with linear and interaction terms. The baseline marker X alone detects 18% of cases and is indicated by a black dashed line. Markers have 0 correlation in controls and correlation ρD in cases.

2.2.3. Mixture Bivariate Binormal Markers

Diseases are often heterogeneous in nature. This is particularly true for cancer where it is thought that unknown subtypes exist. Correspondingly, different biomarkers may be associated with different subtypes. The following statistical model represents this concept:

and

That is, in cases the distribution for (X, Y) is a mixture of three distibutions. An interpretation is that X is discriminatory in a proportion pX of cases, while Y is discriminatory in a different proportion pY of cases. The ROC curves for X and Y alone are mixture binormal. In particular, for X we have:

with corresponding AUC:

The ROC and AUC for Y take the same forms, with μY replacing μX and pY replacing pX. Observe that there are two parameters that define the marginal performance of each marker, (pX, μX) for X and (pY, μY) for Y. We set the performance of X as before, such that ROCX(0.05) = 0.183, which is achieved under two configurations that we consider here, (pX, μX) = (0.15, 3.17) and (pX, μX) = (0.4, 1.35). The marginal performance of Y ranges from useless, ROCY(0.05) = 0.05, to that of X, ROCY(0.05) = 0.183. This corresponds to μY ranging from 0 to 3.17 for pY = 0.15 and μY ranging from 0 to 1.35 for pY = 0.4. Note that for a fixed overall performance criterion, smaller values for the proportion of marker-specific cases, p, correspond to larger values of μ, which in turn correspond to better detection of those marker-specific cases. Moreover, note that the proportion of marker-specific cases imposes a bound on the maximum performance that can achieved by that marker. For example, when pY = 0.15, the maximum ROCY(0.05) is 0.193, no matter how large μY may be. Intuitively, this makes sense in the given context of heterogeneous diseases, where a marker may have good discriminatory ability within a particular subtype, but if that subtype occurs very rarely the marker may not be very useful in the overall classification of subjects as positive or negative for the disease.

Figure 5 shows the increment in performance gained by combining Y with X. Again, these calculations were made using numerical methods with a large simulated dataset since deriving an analytic formula for ROCX,Y(f) was not feasible. Gains in performance are small when Y is comparable with X (ROCY(0.05) = 0.183), about 10% when pX = 0.15 and 8% when pX = 0.4 (Figure 5(a)). The gains are miniscule when ROCY(0.05) = 0.100. It is interesting that for ROCY(0.05) = 0.183, we see a somewhat larger performance increment when pX = 0.15 (ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.274 at pY = 0.25), compared to when pX = 0.4 (ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.249 at pY = 0.25). Moreover, while ROCX,Y(0.05) generally stays constant over varying pY, there is a slight upward spike observed for pY < 0.2. This result is noteworthy since it implies that for a fixed marginal performance, markers with lower subtype prevalence are to be preferred. That is, the larger separation of marker values between marker-specific cases and controls for pY = 0.15 makes a joint classification rule that is more effective. This idea is illustrated in Figure 5(b), where a larger increment occurs for pY = 0.15 than for pY = 0.4. An analogous result holds for pX and we see that the largest increment of 10% occurs for the setting where both subtypes have lower prevalence but have markers that are highly sensitive. Nevertheless we see that the increment in performance is fairly small in all settings for the mixture bivariate binormal setting.

Figure 5. Mixture binormal markers.

Detection of cases by the combination (X,Y) and the threshold that leads to FPR = 5%. The performance of X alone is indicated by a black dashed line that remains constant at ROCX(0.05) = 0.183. Shown here are results for when (a) ROCY(0.05) is fixed and the combination performance is observed over pY varying from 0.15 to 1 - pX and (b) pY is fixed and ROCY(0.05) is varied from 0 to 0.183.

As shown in Figure 2(c), the optimal marker combination in the mixture bivariate binormal setting again contains non-linear terms for X and Y. The risk function, r(X,Y), is a monotone function of

In Figure 2(c), we use this optimal combination as well as a linear combination based on a logistic model to classify marker values as positive or negative at FPR = 5% and FPR = 10%. While the flexibility of the optimal rule fits the structure of the data better, a linear boundary can perform relatively well here (also see Web Figure A 3). When pX = 0.15 and ROCY(0.05) = 18.3%, ROCX,Y(0.05) = 29% using the optimal rule versus ROCX,Y(0.05) = 24% using the linear rule. The linear rule gains about half the increment gained by the optimal rule across all values of pY. When pX = 0.4 and ROCY(0.05) = 18.3%, ROCX,Y(0.05) = 27% using the optimal rule versus ROCX,Y(0.05) = 23% using the linear rule for pY = 0.15. As pY increases, the performance of the linear rule closely approximates that of the optimal rule.

2.3. Adding a Binary Marker

Our focus so far has been on the bivariate binormal setting where both X and Y are continuous markers. Motivated by recent efforts to study the potential of genetic markers (such as single nucleotide polymorphisms) to add to currently existing markers, we now consider settings where Y is a binary marker. Additionally, this presents a violation of the normality assumption and allows us to explore the impact of this violation on the results shown thus far.

The baseline marker X is as before, binormal with μX = 0.742, so that AUCX =0.7 and ROCX(0.05)=0.183. To generate the binary marker Y, we first generate a continuous latent marker YC using model (1) and then dichotomize using the threshold Φ−1(0.95), Y = I(YC > Φ−1(0.95)), that fixes FPRY = 0.05. By choosing μYC = (0, 0.36, 0.742) we have corresponding TPRY = (0.050, 0.100, 0.183). Note that although we simulate X and YC with specified correlation ρC ∈ (0, 1), the correlation between X and the dichotomized marker Y is smaller and no longer exactly equal in cases and in controls. The reduction in correlation is not surprising as dichotomizing YC eliminates some of the correlation between markers X and YC(See Web Table B.1 for details).

In the current setting, an analytic formula for the optimal combination is not feasible and so as before we use numerical methods with a large simulated dataset to derive the combination. Specifically, we fit a logistic regression model to a very large simulated dataset containing linear terms for X and Y, an interaction term and a quadratic term for X. Calibration plots [14] indicated good calibration.

Combination performance results are provided in Appendix B. We found that the main conclusions regarding the relative performance of different candidate markers are similar to those we made earlier for continuous markers. For a candidate marker that has good marginal performance (TPRY = 0.183), the biggest performance gain is achieved when ρ = 0 (ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.236) and it reduces to no gain as ρ increases. On the other hand, a marker with poor marginal performance (TPRY = FPRY = 0.05) provides no improvement when ρ = 0, but when the correlation is high, the improvement is more substantial, ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.266. Gains were smaller using a linear combination of X and Y derived from fitting a logistic regression model containing only linear terms for the markers. For example, a marker with poor marginal performance (TPRY = FPRY = 0.05) led to ROCX,Y(0.05) = 0.248 when the correlation was high. We note that performance gains from a binary Y are smaller than gains from the latent continuous Y, reflecting that information is lost by dichotomizing a continuous marker.

We also explored binary Y generated by dichotomizing a continuous latent marker YC that has unequal correlation with X in cases versus in controls (as per model (2) of the bivariate binormal unequal correlation setting). General findings are again similar to those for the continuous marker setting (Web Figure B.1(b)). Better marginal performance of Y generally leads to better performance for (X, Y) and the greater the difference in correlation between cases and controls, the better the combination performance.

Finally, we considered the mixture setting, where X and Y are discriminatory in separate proportions of cases, pX and pY, respectively. Observe that when Y is binary, this corresponds to Y = 1 in the proportion pY of cases and 0 for all controls and 1 − pY of cases. This scenario is more straightforward than the scenario of continuous Y. Combining Y with X does not increase the FPR but does increase the TPR by pY. The magnitude of performance improvement is simply pY.

2.4. General Implications of Numerical Studies

In the above numerical studies we investigated the incremental value of a continuous marker Y under three specific scenarios for the joint behaviors of continuous X and Y. We found that under the mixture bivariate binormal model and the classic bivariate binormal model with equal variances in cases and controls and zero correlation, the increment in performance is typically very small. This holds true even when Y’s performance is comparable with that of X. We found much larger gains in performance under alternative bivariate binormal scenarios including: novel markers with poor marginal performance but highly correlated with X conditional on disease status; and novel markers uncorrelated with X in controls but highly correlated with X in cases (and vice versa).

Our results focused on settings where X is a continuous scalar valued normally distributed baseline variable. However our results apply somewhat more generally. The baseline variable could be a specified combination of predictors such as a standard risk score (e.g. Framingham score) or a combination score derived from training data. Note that if the score is a weighted average of predictors, such as the score from fitting a logistic regression model, it may be approximately normally distributed according to the central limit theorem thus fitting the paradigms we studied here. We also noted earlier that our results apply to markers that are normal after some unspecified monotone transformations, since the ROC curve is unchanged by such transformations of the data [7].

Nevertheless the set of scenarios we covered is limited. In practice, markers may not follow a mixture model or a binormal model or they may have different variances in cases versus controls, for example. Our goal, however, is not to cover all possible distributions of two markers, nor is this even possible. Therefore, our results do not provide specific guidance on which markers are likely to yield substantial improvements in performance in practice. Rather our results suggest casting a wide net in the search for novel markers. When candidate markers with a range of marginal performance and correlations are available, restricting the search to those that have good marginal performance or low correlation, as is common practice, and ignoring other potentially good options, is ill advised. A better strategy may be to assess the joint performance of existing and new markers, taking into account their correlation conditional on disease status. We also showed that combining markers using only linear terms may be too restrictive. In some scenarios much better combinations may be obtained with the inclusion of non-linear terms.

3. Comparing Broad and Standard Strategies for Selecting Marker Panels

We now turn to strategies for using data to select a small subset of markers from a large set of markers for further study with the goal of developing a marker combination with good classification performance. The standard approach is to rank markers according to their marginal classification performance, to select the top K ranking markers, and to evaluate all combinations of those K markers. The results of our numerical studies suggest that this approach may miss markers that perform extremely well in combination. Therefore we investigate here a broader selection strategy that evaluates combinations of all available markers regardless of marginal marker performance. To keep the problem simple and hopefully more insightful, we first consider only pairwise combinations as above and later address combinations of more than two markers.

3.1. Colon Cancer Dataset

Simulations studies that generated data from the models presented in sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 are described in Web Appendix C. Here we present a real dataset concerning autoantibodies to tumor antigens that may be useful for cancer screening. We use a dataset comprised of 2100 protein microarray autoantibody measurements from 70 case subjects with colon cancer and 70 control subjects. We transformed each marker so that its distribution in controls was normal with mean 0 and standard deviation 1.

First, we show examples from this real dataset to demonstrate that the settings considered in Section 2 appear in practice. Table 1 presents three marker combinations from the dataset that are formed by adding a marker with a marginal AUC of 0.521 to baseline markers with marginal AUCs ranging from 0.708 to 0.712. In each example, the two markers have similar variances in cases, by definition they have equal variances in controls and they have high correlation in cases (ρD) and in controls (ρD̄), with ρD and ρD̄ almost equal. AUCs obtained using 10-fold cross-validation averaged over 100 repetitions show substantial improvements over either marker on its own (0.730–0.747 compared to 0.708–0.712).

Table 1.

Examples of marker pairs from the colon cancer dataset, where both markers have similar variances in cases and the correlation between markers is similar in cases and controls. The last column presents AUCs obtained from 10-fold cross-validation averaged over 100 repetitions.

| Marginal AUC |

|

|

ρD̄ | ρD | AUC of Linear Combination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | ||||||||

| 1. | 0.708 | 0.521 | 0.817 | 0.785 | 0.528 | 0.550 | 0.730 | ||

| 2. | 0.711 | 0.521 | 0.736 | 0.785 | 0.613 | 0.547 | 0.747 | ||

| 3. | 0.712 | 0.521 | 0.738 | 0.785 | 0.693 | 0.620 | 0.740 | ||

Next, we illustrate standard and broader selection strategies using a random set of 100 of the 2100 markers measured on a random subset of 70 subjects. These 70 subjects were used as the training dataset to select the top P = 10 marker combinations under both strategies. We reserved the data on the remaining 70 subjects to act as a test dataset for performance evaluation.

In the standard strategy, all pairwise combinations of the K = 10 markers with best marginal performances were considered. Pairs were combined using logistic regression and their AUCs estimated with cross validation. The P = 10 combinations with highest cross-validated AUCs were then evaluated on the independent test dataset. In the broad strategy, logistic regression was applied to all pairs regardless of their marginal performance and the P = 10 combinations with highest cross-validated AUCs were evaluated in the test dataset. We used logistic regression with interaction terms in one analysis and logistic regression without interaction terms in another in order to determine if a more complex model yielded better combinations.

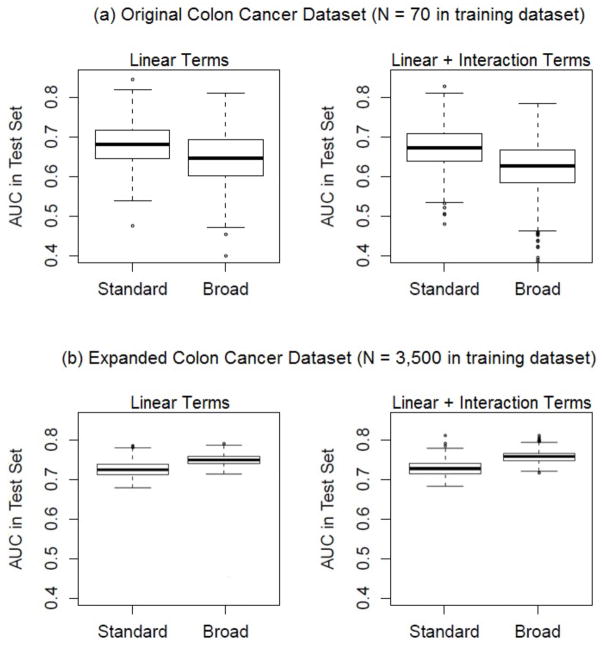

Results for a single dataset (see Web Table D.1) show that the broad strategy yields worse combinations than the standard strategy in this setting. However, no general conclusions can be drawn from results of one dataset as we found substantial variation in results with the split of the dataset into training and test components and with the random sample of 100 markers included. Therefore we repeated this exercise 100 times and summarized the results in Figure 6(a). Each boxplot contains 1000 AUC values, showing distributions of the AUCs estimated with the test dataset for the top 10 marker combinations derived from the training dataset. Table 2(a) shows the proportion of repetitions in which the kth ranking combination derived from the broad strategy in the training dataset had a higher test dataset AUC than that for the kth ranking combination derived from the standard strategy. We see that in general the broad strategy yields worse marker combinations than the standard strategy, not better combinations as we had hoped. Use of more complex combinations that include an interaction term led to even poorer performance. These disappointing results however were reversed when we repeated the exercise in a larger dataset. Since we did not have access to a large real dataset, we expanded the colon cancer dataset by a factor of 50 by replicating it and adding to each biomarker value normally distributed noise with mean 0 and standard deviation 0.01. Results in Figure 6(b) and Table 2(b) show that in this much larger dataset, the broad strategy finds better performing marker combinations than does the standard strategy. For example, the top marker pair derived with the broad strategy had better performance than the top marker pair derived with the standard strategy in 95% of the repetitions when a logistic model with interaction was used for combining markers. Moreover, including an interaction term in the logistic model was beneficial in this dataset. We see that using the broad strategy, the top marker combination derived from the model including an interaction had AUC higher than the top marker combination derived from the model without interaction in 74% of the repetitions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of standard and broad strategies, using 100 repetitions of different sets of 100 markers and training-test data from the (a) original and (b) expanded colon cancer datasets.

Table 2.

Proportion of repetitions in which the kth ranking combination in the training dataset had a higher test dataset AUC from the first strategy than from the second strategy.

| (a) Original Colon Cancer Dataset (N = 70 in training and test datasets)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker Rank | Broad, no interaction > Standard, no interaction | Broad, w/interaction > Standard, w/interaction | Broad, w/interaction > Broad, no interaction |

| 1 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.44 |

| 2 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.38 |

| 3 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.38 |

| 4 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.35 |

| 5 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| 6 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| 7 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| 8 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.35 |

| 9 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.45 |

| 10 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.37 |

| (b) Expanded Colon Cancer Dataset (N = 3,500 in training and test datasets)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker Rank | Broad, no interaction > Standard, no interaction | Broad, w/interaction > Standard, w/interaction | Broad, w/interaction > Broad, no interaction |

| 1 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.74 |

| 2 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.67 |

| 4 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.74 |

| 5 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.73 |

| 6 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.77 |

| 7 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.74 |

| 8 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.69 |

| 9 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.71 |

| 10 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.71 |

3.2. Going Beyond Pairwise Combinations and Sample Size Considerations

To further study the impact of sample size on which strategy performs better and to address the need in practical settings to go beyond combinations of just two markers, we carried out more extensive simulation studies. For increasing sample sizes of the training and test sets (Ntrain = Ntest), we compare the broad strategy to the standard strategy with two-marker and three-marker combinations, formed using logistic models with and without interaction terms as before. Figure 7 (left panel) and Web Figure D.1 show that when a simple model with only linear terms is used and the sample is small (Ntrain = 70), the broad strategy has poorer performance than the standard strategy for both two- and three-marker combinations. Not surprisingly, performance of the broad strategy is worse for three-marker combinations than for two-marker combinations. A much larger sample of size Ntrain = 350 is needed for the broad strategy to have similar performance to the standard strategy for two-marker combinations and to surpass the standard strategy for three-marker combinations. Interestingly, at this point, three-marker combinations perform better than two-marker combinations.

Figure 7.

Comparison of standard and broad strategies with two- and three-marker combinations for varying sample sizes. We used 100 repetitions of different sets of 100 markers and training-test data for models with (a) linear terms only and (b) linear and interaction terms.

With a more complex model that includes an interaction term, we see from Figure 7 (right panel) and Web Figure D.2 the phenomenon we saw earlier (Figure 6(a)) — for a small sample (Ntrain = 70), overfitting in the training set leads to poorer performance compared to when the model contains only linear terms. Three-marker combinations suffer more from the addition of three interaction terms than do two-marker combinations from the addition of a single interaction term. For larger sample sizes, however, performance of the more complex model surpasses that of the simple model. In fact, for a training sample size as small as 350, the broad strategy using three markers and interaction terms performs far better than all other combinations. Finally, when Ntrain = 700, performance is further improved in all cases and for combinations of three markers with linear and interaction terms, the broad strategy performs even better than the standard strategy (median AUCX,Y = 0.789 versus AUCX,Y = 0.769). Interestingly, the marginal performance of markers selected by the broad strategy is lower (median AUC = 0.672), compared to the marginal performance of markers selected by the standard strategy (median AUC = 0.709) (See Web Figure D.3).

We showed in Section 3.1 for two-marker combinations that using a more complex model and a broad search strategy can add significantly to performance if a large enough sample is available. Here we see that given a large enough sample, combining more than two markers can further add significantly to performance. However, if the sample is too small, combining more than two markers can harm combination performance. In practice, we might use pilot data in this manner and carry out simulations to decide on the required sample size and appropriate discovery strategy in planning the next study. In the current example, Figure 7 shows that for a target AUC of 0.65, a training set of size 70 and the standard strategy that combined 2 markers using a simple model should be chosen. For a target AUC of 0.70, one would require a larger training set of size 140 and the standard strategy would still perform better than the broad strategy. For a target AUC of 0.75, however, a training set of size 350 would be required and the broad strategy (with 3 markers) and a more complex model that includes an interaction term would now be optimal.

4. Discussion

Results from the colon cancer dataset suggest that a broad search strategy can be useful in identifying markers for combination. More dramatic results were observed with simulated datasets where markers with joint distributions discussed earlier in this paper were included among candidate markers available (See Web Appendix B) and with expanded colon cancer datasets. Results also showed advantages for including interaction terms in the combination score. Additionally we saw from the colon cancer dataset that going beyond pairwise combinations to just three-marker combinations can dramatically improve performance. Advantages of the broad search, flexible score and combining more markers are however only realized when large datasets are available for identifying the combinations. In current practice, datasets for identifying markers are usually small. We recommend that much larger sample sizes be used for these studies in the future.

How should one choose the sample size of a marker panel identification study? The sample size depends on the clinical context in which the marker panel is to be used. Given the context, one would set an appropriate target and look for combinations accordingly. For example, for screening purposes, it is common to fix a low false positive rate (FPR) and look to improve the corresponding true positive rate (TPR). In cancer screening, as long as a low FPR, flow, is maintained, relatively low values of ROC(flow) may be acceptable targets. On the other hand, diagnostic tests must achieve a high TPR in order to be considered valuable. A higher FPR, fhigh is accepted and we look to improve the corresponding ROC(fhigh). Alternatively, interest may lie in improving the area under the ROC curve (AUC) or some other performance measure and again, different targets may be set depending on the context. For a low target, a smaller sample size and the standard strategy may be sufficient, but when the target performance is higher, one would need to broaden the search strategy which would also require a larger sample size. Therefore, we cannot derive a sample size at which one strategy would generally be better than the other. Instead, we recommend performing simulation studies based on hypothesized joint distributions for biomarkers. By varying the size of the simulated dataset one can determine the sample size at which good marker combinations are likely to rank highly and are therefore likely to be pursued in further studies. If pilot data are available one could base simulation studies on that, as we did with the colon cancer data. Assuming these data were pilot data available for guiding the design of another panel identification study, expanding the pilot dataset allowed us to determine at what size the selected combination or combinations are highly likely to have performance that is at or above a target level.

Note that in practice combining markers does not always lead to improvements in performance. In particular, non-optimal combinations may have worse performance than either marker on its own. We saw this in the left panel of Figure 4, for an incorrect form of the risk model lacking interaction terms. A simple example involving the equal correlation bivariate binormal model is reported in Web Appendix E. One must also be cognizant that sampling variability in coefficient estimates for risk models is a factor that leads to suboptimal marker combinations.

In summary, we have shown that the practice of restricting attention to markers with good marginal performance has the potential to miss certain marker combinations that perform extremely well. Although we mainly focused on combinations of only two markers, the implication is clearly true for combinations of more than two markers as well, as indicated by our investigation of three-marker combinations. We showed that by broadening the strategy for assembling marker panels to include markers with poorer marginal performance that appear to contribute substantially to combination performance, better marker combinations may be found. However, large sample sizes will be required for these marker panel identification studies in order for the broadened strategy to be fruitful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health [CA129934, CA086368, GM054438]. The authors are grateful to Dr Samir Hanash of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center for allowing us to use the colon cancer dataset.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Americal Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:882–890. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson GL, McIntosh M, Wu L, Barnett M, Goodman G, Thorpe JD, Bergan L, Thornquist MD, Scholler N, Kim N, O’Briant K, Drescher C, Urban N. Assessing Lead Time of Selected Ovarian Cancer Biomarkers: A Nested Case-control Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102:26–38. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gail MH. Discriminatory accuracy from single-nucleotide polymorphisms in models to predict breast cancer risk. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:1037–1041. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntosh MW, Pepe MS. Combining several screening tests: optimality of the risk score. Biometrics. 2002;58:657–664. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2002.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neyman J, Pearson ES. On the problem of the most efficient tests of statistical hypotheses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London A. 1933;24:289–337. doi: 10.1098/rsta.1933.0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metz CE, Kronman HB. Statistical significance tests for binormal ROC curves. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 1980;22:218–243. doi: 10.1016/0022-2496(80)90020-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. pp. 81–85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyon I, Elisseeff A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2003;3:1157–1182. doi: 10.1162/153244303322753616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger AP, Deibl M, Steiner H, Bektic J, Pelzer A, Spranger R, Klocker H, Bartsch G, Horninger W. Longitudinal PSA changes in men with and without prostate cancer: Assessment of prostate cancer risk. The Prostate. 2005;64:240–245. doi: 10.1002/pros.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntosh MW, Urban N, Karlan B. Generating longitudinal screening algorithms using novel biomarkers for disease. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2002;11:159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skates SJ, Xu FJ, Yu YH, Sjovall K, Einhorn N, Chang Y, Bast R, Jr, Knapp R. Toward an optimal algorithm for ovarian cancer screening with longitudinal tumor markers. Cancer Supplement. 1995;76(10):2004–2010. doi: 10.1002/1097. – 0142(19951115)76: 10+ < 2004:: AID – CNCR2820761317 > 3.0.CO; 2 – G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skates CJ, Pauler DK. Screening based on the risk of cancer calculation from Bayesian hierarchical change-point models of longitudinal markers. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:429–439. doi: 10.1198/016214501753168145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slate EH, Cronin KA. Changepoint modeling of longitudinal PSA as a biomarker for prostate cancer. School of Operations Research and Industrial Engineering, Technical Report. 1997:1189. http://hdl.handle.net/1813/9073.

- 14.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1989. Section 5.2.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.