Abstract

The objectives of this review article are to facilitate deeper research and better policy analysis for healthy aging, which not only means surviving to old ages in good health, but also mean the economics and society of our country would be aging healthily, with sound policy and intervention programs. Toward these objectives, we introduce the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), which has been conducted by Center for Healthy Aging and Development Studies, National School of Development of Peking University since 1998. We present a comprehensive and summarized introduction of the CLHLS study design, sample distributions, contents, general quality assessment and availability of the CLHLS data collected. Such an introduction would be helpful for our colleagues who may be interested in using this unique and more-than-fourteen-year longitudinal survey data resource for deeper interdisciplinary research and better policy analysis on healthy aging. To illustrate how the unique data resources of CLHLS may be useful, we also summarize and discuss ten selected healthy aging policy related research based on data from the CLHLS. Finally, we discussed the future perspectives using the unique and rich CLHLS datasets.

1. Rapid Aging and Important Needs on Deeper Research and Better Policy for Healthy Aging

The population of China, which is about one-fifth of the world’s total, is aging rapidly due to rapid declines in both fertility and mortality. Under the medium or low mortality assumptions, the total number of elderly aged 65+ in China is estimated to increase dramatically from 111 million in 2010 (8.2% of the total population) to 337 to 400 million in 2050 (23.9% to 26.9% of the total population); the number of oldest-old aged 80+ who most likely need daily life assistance were about 19.3 million in 2010, but it will climb extraordinarily to about 107 to 150 million in 2050, respectively (Zeng and George, 2010; Zeng, Chen and Wang, 2012). The average annual rate of increase of the oldest-old from 2000 to 2050 is about 4.4~5.1 percent in China, more than twice that of the U.S. and other industrialized countries (U.N. 2011). The main reason why the number of oldest-old will climb so quickly especially after the year 2030 is that China’s “baby boomers,” who were born in the 1950s and 1960s, will fall into the category of the “oldest-old” after 2030.

Although fertility in rural areas in China is much higher than that in urban areas, aging problems will be much more serious in rural areas because of the continuing massive rural-to-urban migration are almost all young people. If the 2000-census observed extremely young age structure of the rural-to-urban migrants remains unchanged, the proportion of elderly in 2050 will be 34.2% vs. 20.5% or 39.6% vs. 22.7% percent in rural and urban areas under the medium or low mortality scenarios respectively.

The medium mortality scenario, which is similar to the medium variant adopted in almost all international (including UN, EU and US Census Bureau) and domestic projections, assumes that the Chinese life expectancy at birth for both sexes combined increases from 71.4 years-old in 2000 to about 79 years-old in 2050, 3.1 years-old lower than that in Japan in 2009. The low mortality scenario initially made by a few scholars (Ogawa, 1988; Zeng and George, 2010) assumes that the Chinese average life expectancy would be 84.9 years-old in 2050, 2.8 years-old higher than that in Japan today. The medium or the low mortality scenarios imply an annual growth rate of 0.20% or 0.35% of the Chinese life expectancy during the first half of this century.

We expect that China’s path of mortality decline will be at least close to or even exceed the low mortality scenario outlined above for mainly two reasons. First, the observed recent mortality reduction and the ongoing quick improvements in living standard, medical care and old age insurance programs in China may support the low mortality scenario assumption. For example, the data from 2000 census and the 1.31% population survey in 2005 (with a sample size of 17.1 million persons) shown that the Chinese life expectancy increased from 71.4 years-old in 2000 to 73.0 years-old in 2005 -- an observed annual growth rate of 0.44%, that is higher than the annual growth rate assumed in the medium and low mortality scenarios by 125 and 28 percent, respectively. Second, the steadily continued morality decline especially at old ages observed in the developed countries in the past a few decades may be the approximate pathway in which the Chinese mortality evolves in the next decades. Consequently, in the middle of this century, the Chinese elderly aged 65+ and oldest-old aged 80+ will very likely be close to or even exceed 400 million and 150 million, respectively. If the current age pattern of the rural-to-urban migrants remains unchanged, the proportion of elderly aged 65+ will be close to or exceed 39.6% and 22.7% in rural and urban areas!

Similar to the Chinese case, many other developing countries (such as South Korea, Mexico and India) will also subject to the rapid growth of elderly population in both numbers and percent in the first half of this century (U.N., 2009). Clearly, it is strategically important to investigate the effects of socioeconomic, behavioral, environmental, genetic factors and their interactions on healthy aging towards deeper interdisciplinary research and better policy which will significantly benefit elderly population and all other members of the society.

Keeping our objectives towards deeper research and better policy in mind, we introduce in the next Section the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), which has been conducted by Center for Healthy Aging and Development Studies, National School of Development of Peking University since 1998. Our intension is to present a comprehensive and summarized introduction of the CLHLS study design, sample distributions, contents, general quality assessment and availability of the CLHLS data collected. Such an introduction would be helpful for our colleagues who may be interested in using this unique and more-than-fourteen-year longitudinal survey data resource for deeper interdisciplinary research and better policy analysis on healthy aging. To illustrate how the unique data resources of CLHLS may be useful for deeper research and better policy analysis, the third Section of this paper summarizes and discusses several selected healthy aging policy related research based on data from the CLHLS. The last section discusses the future perspectives and concludes the paper.

Note that the concept of “healthy aging” used throughout this article not only means surviving to old ages in good physical/mental health and active social participation, but also mean the economics and society of our country would be aging healthily, with sound policy and intervention program supports.

2. Introduction of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey

2.1 Why conducting the CLHLS?

As discussed in the Introduction section above, population of China is aging rapidly due to rapid declines in both fertility and mortality. Oldest-old persons are much more likely to need help in daily living as compared to the younger elderly. The CLHLS data, for example, show that the prevalence of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) disability increases dramatically with age, from <5% at ages 65–69 to 20% at ages 80–84 and 40% at ages 90–94; the oldest-old also consume services and medical care at a much higher rate than younger elderly (Torrey,1992). However, China and many other developing countries where populations are aging rapidly lag behind in economic and social welfare development, and face the serious challenges of “becoming aged before rich,” with little preparation for the aging society.

Population aging accompanied with rapid growth of the oldest-old and large increase in life expectation is unavoidable. A couple of fundamental questions arise: is it possible to realize compression of morbidity (Fries 1980), or at least dynamic equilibrium (Manton 1982), rather than expansion of disability (Gruenberg 1977)? Why do some people enjoy good health up to very old ages but the others suffer severe disability and diseases and died earlier? The answers to these questions will determine quality of life not only for the elderly but also for all members of society. So far, however, there are very few clear answers to these important questions. One reason is because the relevant issues are very complex, given the fact that health at old ages is jointly determined by various social, behavioral, environmental and genetic factors and their interactions (IOM, 2006). Moreover, there are few good and large sources of longitudinal phenotypic and genotypic datasets available for research and policy analysis to address these critically important questions in China. Clearly, there is an urgent public health need to investigate (with good data resources) factors that underlie successful aging, especially among the oldest-old, a sub-population that will increase dramatically over the next decades with associated high costs of medical care and substantial burden of disability.

In the U.S., Canada, Europe, and some Asian and Latin American countries, efforts have been made to attract the attention of academics and policy makers to the concerns of the oldest-old, and some countries around the world have collected data from large samples of the old, with an over-sampling of the oldest-old (Suzman, Willis and Manton 1992; Vaupel et al. 1998). Before the CLHLS study was launched in 1998 in China, however, little attention had been paid to ensure sufficient representation of the oldest-old in national surveys, and most studies on the elderly included few subjects aged 80 and older. Almost all published official statistics were truncated at ages 65 or 80 then. The surveys on the elderly had sub-sample sizes far too small for the proper evaluation of the oldest-old. For example, 20,083 elders aged 60 and older were interviewed in the 1992 Chinese national survey on support systems for the elderly; but among them, only 84 were aged 90+. These small sub-sample sizes made a meaningful analysis of the oldest-old sub-population impossible.

The CLHLS has been conducted in China since 1998 to fill in the data and knowledge gaps for scientific studies and policy analysis concerning healthy aging. Our general goal is to shed new light on better understandings of the determinants of healthy aging of human beings. We have been compiling extensive longitudinal home-interview data on a much larger population of oldest-old aged 80 and older than has previously been studied, with a comparative group of younger elders aged 65–79. Important measures include health status, disability, death and survival, demographic, family, socio-economic, income level, care needs and costs for elderly, and behavioral risk-factors related to mortality and healthy aging. We use demographic, econometric and statistical methods to analyze data culminating from the longitudinal surveys. We want to determine which factors, out of a large set of social, economic, behavioral, environmental, and genetic factors, play an important role in healthy aging. We also aim to draw societal and governmental attention to scientific studies, sound policy-making and practical program interventions for enhancing the well-being and life quality of the oldest-old and all other members of our society (Zeng et al., 2001). The large population size, the focus on healthy aging (rather than on a specific disease or disorder), the simultaneous consideration of various risk factors, and the use of analytical strategies based on demographic, economic and social concepts make this an innovative data collection and research project.

2.2 Study design

2.2.1 CLHLS in about half of the counties and cities in the 22 provinces

The baseline survey and the follow-up surveys (with replacement for deceased elders) were conducted in a randomly selected half of the counties and cities in 22 of China’s 31 provinces in 1998, 2000, 2002, 2005, 2008–2009, and 2011–20122. Han Chinese people, who generally report age accurately, are the overwhelming majority in the 22 surveyed provinces. The surveyed provinces are Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Hebei, Beijing, Tianjing, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shangdong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Sichuan, and Chongqing. The population in the survey areas constitutes about 85 percent of the total population in China in the CLHLS 1998 baseline survey.

In our baseline survey, we tried to interview all centenarians who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study in the sampled counties and cities; for each centenarian interviewee, we interviewed one nearby octogenarian and one nearby nonagenarian of predefined age and sex. In the 2002, 2005, and 2008–2009 waves, we interviewed approximately three nearby elders aged 65–79 of predefined age and sex in conjunction with every two centenarians. In our 2008–2009 wave, we recruited one nearby un-related middle age control participant aged 40–59 for each of centenarian.

In our CLHLS 1998, 2000, 2002, 2005, and 2008–2009 waves, we tried to interview all centenarians who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study in the sampled areas over the 22 provinces, in order to keep a large sub-sample of centenarians in each of the waves. Those elderly who were interviewed at an age younger than 100 but subsequently died before the next wave were replaced by new interviewees of the same sex and age (or within the same 5-year age group). “Nearby” is loosely defined – it could be in the same village or in the same street, if available, or in the same town or in the same sampled county or city district. The predefined age and sex are randomly determined, based on the randomly assigned code numbers of the centenarians, to have comparable numbers of males and females at each of the age groups.

To avoid the problem of small sub-sample sizes at the more advanced ages, we did not follow the proportional sampling design procedure, but instead interviewed nearly all centenarians and over-sampled the oldest-old of more advanced ages, especially among males in the sampled counties and cities. Consequently, appropriate weights based on the census and the CLHLS data need to be used to compute the averages of the age groups below age 100, but no weights are needed when computing the average of the centenarians. The method for computing the age-sex and rural-urban specific weights and the associated discussions are presented in the Appendix of Chapter Two of the book by Zeng et al. (2008) and available at the CLHLS Webpage.

To maintain a large enough sample size, we replaced the deceased respondents by recruiting new participants with in the same gender and roughly the same age as that of the deceased respondents in our 2000, 2002, 2005, and 2008–2009 follow-up waves. But we conducted the follow-up interviews only without new participants in the all other sampled areas than the eight longevity areas in our 6th wave of CLHLS in 2011–2012, while the new participants were also recruited to replace the deceased ones in the eight longevity areas.

2.2.2 More in-depth CLHLS study in the longevity areas

In order to address the interesting and puzzling questions of why some areas have much more healthy and long-lived individuals than the average, we have added in-depth studies in seven longevity areas where the density of centenarians is exceptionally high as part of the 5th wave of CLHLS in 2009, and eight longevity areas (the seven plus a new one) as part of the 6th wave of CLHLS in 2012. The in-depth studies include more sophisticated health exams by medical personnel and blood and urine sample collections for health biomarkers analysis, in addition to the home-interviews which are the same as in the other survey areas. One challenge was how to select the appropriate areas (counties/cities) where the density of centenarians is truly and exceptionally high as sites for our in-depth study. We fortunately have a good opportunity to perform this task efficiently. The opportunity is due to the fact that the Ministry of Civil Affairs authorized Chinese Society of Gerontology (CSG) to settle up a committee and program to evaluate and officially designate names of “Chinese Longevity Areas (CLA)”. Consequently, The CSG Committee formulated and officially announced the standards, application guidelines and expert-evaluations procedure concerning designation of the Chinese Longevity Areas. The standards set up the criteria of a qualified longevity area, which include exceptionally high density of centenarians and nonagenarians, high life expectancy, and a series of within-area consistency checks including good health status and good environment quality, etc. The guidelines request that the application must be officially submitted by the county or city government with their official stamp and governor’s signatures. After the application passes the preliminary evaluation, CSG will have to contract a professional survey company to validate the age-reporting for all of the centenarians listed in the application and a randomly selected sample of nonagenarians and octogenarians, which amount to about 1.5 times the number of the centenarians in the area. Among the CSG evaluated and officially designated longevity areas, CLHLS team and Chinese Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (China CDC), who conduct the field work as our research partner, selected seven in 2009 and eight (the seven plus a new one) in 2012 as the sites of our in-depth study. They are: Chen Mai county (in Hainan province), Yong Fu county (in Guangxi province), Ma Yang county (in Hunan province), Zhong Xiang city (in Hubei province), Xia Yi county (in He Nan province), San Shui city (in Guangdong province), and Lai Zhou city (in Shandong province) in 2009, and these seven areas plus Ru Dong county (in Jiangsu province) in 2012.

In order to facilitate cross-regional comparisons between the longevity areas, and the other ordinary areas, the sampling design and the questionnaires used in the longevity areas were the same as those in the other sampled countries/cities. In addition, the data collection and analysis in the longevity areas were more in-depth in the following three aspects: (1) we conducted substantially more sophisticated health examinations with collections of blood and urine samples by medical doctors or registered nurses who are members of China CDC network; (2) unlike 2011 follow-up survey only in the other sampled areas, in our in-depth survey in eight longevity areas in 2012, we tried to interview all centenarians and replaced those participants who were non-centenarians and died before the survey; (3) we recruited one biological child for each centenarian interviewee to be study subjects.

2.2.3 Sub-sample of adult children of the elderly interviewees in the eight Eastern coastal provinces

With support from the Taiwan Academy Sinica and Mainland China Social Sciences Academy, we added a sub-sample of 4,478 elderly interviewees’ adult children aged 35–65 in 2002. The adult children sub-sample covers the eight mainly Eastern coastal provinces of Guangdong, Jiangsu, Fujian, Zhejiang, Shandong, Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangxi among the 22 provinces of our CLHLS survey. If an elderly interviewee had only one eligible child (i.e., aged 35–65 and living in the sampling areas), that child was interviewed. If an elderly interviewee had two eligible adult children, the elder child was interviewed if the elderly interviewee was born in the first 6-months, and the younger child was interviewed if the elderly interviewee was born in the second 6-months. If an elderly interviewee had three eligible adult children, the eldest, the middle, or the youngest child was interviewed if the elderly interviewee was born in the first 4-months, second 4-months or the third 4-months, and so on. Among the 4,478 adult children interviewed in 2002, 1,722 sons and 338 daughters co-resided with old parents and 1,410 sons and 1,008 daughters did not co-reside with old parents. Such sample distributions reveal a traditional Chinese social practice: most old parents live with a son; non co-residing sons usually live closer to old parents than do the non co-residing daughters.

The follow-up survey for these 4,478 adult children was conducted in our CLHLS 2005 wave, but no further follow-up after 2005. The main idea is to make a comparative study of intergenerational relationships in the context of rapid aging between Mainland China and Taiwan.

The CLHLS follow-up sub-sample surveys on the adult children and their paired elderly parents in 2002 and 2005 provided unique data for studying intergenerational family relationships/transfers and their impacts on healthy aging. This is particularly relevant in the Chinese cultural and social context, which tends to have a more valued family support system. As compared to other studies following the dyadic approach, our study has unique strengths: the mean age of old parents is 83.6 (SD=11.0) and the mean age of adult children is 50.3 (SD=8.6). About 60 percent of our paired-sample consists of oldest-old parent(s) aged 80–112 with a child who is also elderly or nearly elderly, and about 40 percent of the paired sample consists of old parents younger than age 80 with their relatively younger adult child. Our paired-sample is particularly useful for studying the association of healthy aging with the family relationship between the oldest-old and their elderly children. To our knowledge, no study of this kind, with a large number of pairs of oldest-old parent(s) and their elderly children, has ever been conducted.

2.3 Samples distribution

As shown in Table 1, the CLHLS has conducted face-to-face home-based interviews with 8,959 and 11,161 oldest-old participants aged 80+ in 1998 and 2000, and with 20,428, 18,549, 20,366 and 10,190 participants aged 35–110 in 2002, 2005, 2008–2009, and 2011–2012, respectively.

Table 1.

Sample Distributions of the 1998, 2000, 2002, 2005, 2008–09 and 2011–12 Waves of the CLHLS

| Sex & age | Surviving participants | Interview deceased participants | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2000 | 2002 | 2005 | 2008–09 | 2011–12 | Total | 1998–2000 | 2000–2002 | 2002–2005 | 2005–2008/09 | 2008–2011/12 | Total | |

| Men | |||||||||||||

| 35–64 | --- | -- | 2,945 | 1,834 | 1,908 | 271 | 6,958 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3 | 3 |

| 65–79 | --- | -- | 2,560 | 2,787 | 2,257 | 1,712 | 9,316 | --- | --- | 272 | 218 | 208 | 698 |

| 80–89 | 1,787 | 2,467 | 2,128 | 1,932 | 2,148 | 1,316 | 11,778 | 339 | 481 | 721 | 539 | 542 | 2,622 |

| 90–99 | 1,299 | 1,645 | 1,584 | 1,659 | 1,897 | 1,019 | 9,103 | 574 | 543 | 855 | 880 | 984 | 3,836 |

| 100+ | 481 | 518 | 676 | 581 | 688 | 287 | 3,231 | 348 | 292 | 450 | 429 | 447 | 1,966 |

| Total | 3,567 | 4,630 | 9,893 | 8,793 | 8,898 | 4,605 | 40,386 | 1,261 | 1,316 | 2,298 | 2,066 | 2,184 | 9,125 |

| Women | |||||||||||||

| 35–64 | --- | --- | 1,301 | 732 | 1,892 | 238 | 4,163 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3 | 3 |

| 65–79 | --- | --- | 2,447 | 2,538 | 2,028 | 1,437 | 8,450 | --- | --- | 229 | 172 | 129 | 530 |

| 80–89 | 1,741 | 2,451 | 2,111 | 1,977 | 2,124 | 1,324 | 11,728 | 262 | 367 | 627 | 419 | 406 | 2,081 |

| 90–99 | 1,714 | 2,167 | 2,163 | 2,293 | 2,699 | 1,416 | 12,452 | 612 | 677 | 1,085 | 1,050 | 1,208 | 4,632 |

| 100+ | 1,937 | 1,913 | 2,513 | 2,216 | 2,725 | 1,170 | 12,474 | 1,213 | 930 | 1,635 | 1,502 | 1,712 | 6,992 |

| Total | 5,392 | 6,531 | 10,535 | 9,756 | 11,468 | 5,585 | 49,267 | 2,087 | 1,974 | 3,576 | 3,143 | 3,458 | 14,238 |

| Two sex | |||||||||||||

| 35–64 | -- | --- | 4,246 | 2,566 | 3,800 | 509 | 11,121 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 6 | 6 |

| 65–79 | --- | --- | 5,007 | 5,325 | 4,285 | 3,149 | 17,766 | --- | --- | 501 | 390 | 337 | 1,228 |

| 80–89 | 3,528 | 4,918 | 4,239 | 3,909 | 4,272 | 2,640 | 23,506 | 601 | 848 | 1,348 | 958 | 948 | 4,703 |

| 90–99 | 3,013 | 3,812 | 3,747 | 3,952 | 4,596 | 2,435 | 21,555 | 1,186 | 1,220 | 1,940 | 1,930 | 2,192 | 8,468 |

| 100+ | 2,418 | 2,431 | 3,189 | 2,797 | 3,413 | 1,457 | 15,705 | 1,561 | 1,222 | 2,085 | 1,931 | 2,159 | 8,958 |

| Total | 8,959 | 11,161 | 20,428 | 18,549 | 20,366 | 10,190 | 89,653 | 3,348 | 3,290 | 5,874 | 5,209 | 5,642 | 23,363 |

Among approximately 90,000 interviews conducted in the five waves, 15,705 were with centenarians, 21,555 with nonagenarians, 23,506 with octogenarians, 17,766 with younger elders aged 65–79, and 11,121 with middle-age adults aged 35–64. Data on mortality and health status before dying for the 23,363 elders aged 65–110 who died between the six waves were collected in interviews with a close family member of the deceased (see Table 13).

2.4 Data and DNA samples collections

An interview with some basic physical capacity tests was performed at the interviewee’s home in all waves of CLHLS. The questionnaire design was based on international standards and was adapted to the Chinese cultural/social context and carefully tested by pilot studies and interviews. We emphasized questions that might shed light on risk factors for healthy aging, and we sought to minimize questions that could not be reliably answered by the oldest-old, some of whom may lack education and may have poor hearing and vision. The data collected included family structure, living arrangements and proximity to children, self-rated health, self-evaluation of life satisfaction, chronic disease, medical care, social activities, diet, smoking and alcohol drinking, psychological characteristics, education, occupation before retirement, economic resources, income, care needs and costs of elderly, caregiver and family support, nutrition and some health-related conditions in early life (childhood, adulthood, and around age 60). Activities of Daily Living (ADL), and cognitive function measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were evaluated in all waves in 1998, 2000,2002, 2005, 2008–2009 and 2011–2012. Physical performance capacity was also evaluated in all waves by means of tests of standing up from a chair without using hands, picking up a book from the floor, and turning around 360 degrees. As initially planned, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) questions were not included in the 1998 baseline and 2000 follow-up surveys because the 1998 and 2000 waves interviewed the oldest-old only and the Chinese oldest-old are generally limited in IADL. We added IADL questions in our 2002, 2005, 2008–2009 and 2011–2012 surveys when we expanded our survey to cover both the oldest-old and the young-old aged 65–79.

One unique feature of the CLHLS study is that relatively comprehensive information on the extent of disability and suffering before dying was obtained from a close family member for those interviewees who had died before the next wave. This information includes date/cause of death, chronic diseases, ADL, number of hospitalizations or incidents of being bedridden from the last interview to death, and whether the subject had been able to obtain adequate medical treatment when he/she was sick. If any of the deceased’s ADL activities were disabled or partially disabled, then a question on the duration of the disability (or partial disability) would follow. The number of days spent bedridden before dying was also ascertained. Data on how many days before death the elder did not go outside and how many days before death the elder spent more time in bed than out of bed were collected. Information on socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, such as marital status, family structure, caregivers, financial situation, and living arrangement before death, as well as the caring costs within one month before the death were also collected.

The intensive questionnaires for the adult children sub-samples were admitted in both 2002 initial and 2005 follow-up surveys, including basic demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, relatively detailed life course histories of education, labor force participation, marriage formation and dissolution, attitudes about family values and filial piety to old parents, living arrangements, relationship with and care provided to old parents, care providers’ burdens, household decision-making, home expenses and financial management, own children’s education, etc.

We have collected saliva DNA samples from about 14,000 interviewees aged 40–110 in 2008–09 wave, blood samples from nearly 5,000 participants of the eight longevity areas in 2009 and 2012, and blood dry-spot samples from 4,116 oldest-old aged 80 and older in the CLHLS 1998 baseline survey.

The health exams of 2,035 and 2,862 participants in the seven and eight longevity areas were conducted in 2009 and 2012, respectively, by local certified doctors/nurses who are affiliated with the China Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC), as contracted for this project. The medical personnel used standard instruments to manually check willing participants’ heart, lungs, breast, waist, lymph, limbs, and thyroid, write down impressions and symptoms of disorder if any, and also enquire about the participants’ family disease history and current medications. Finally, the China CDC network medical personnel used a vacuum syringe to collect 5ml of blood samples from the informed willing participants. In addition, the subjects who participated in the health exams in the longevity areas were also interviewed using the same questionnaire as the one used for the respondents in the other sampled counties/cities.

2.5 A general assessment of the quality of the data collected

Accurate age reporting is crucial in studies of the elderly, especially the oldest-old. Older persons in quite many developing countries cannot report their ages accurately (Elo and Preston, 1992; Coale and Kisker, 1986). Age reporting of Han Chinese oldest-old is acceptably accurate, which is rather unique as compared to many other developing countries. Acceptably accurate age reporting among the Chinese Han oldest-old is due to their cultural tradition of memorizing their date of birth for determining important life events such as dates of engagement, marriage, starting to build a residential house, and even for long-distance traveling. This has been confirmed by a wide variety of international and Chinese studies including Coale and Li (1991), Wang et al. (1998), and Poston and Luo (2004). A very recent investigation (Zeng and Gu, 2008) compared various indices of age reporting among the oldest-old and age distributions of centenarians between the CLHLS and data from Sweden, Japan, England and Wales, Australia, Canada, the U.S., and Chile. The analyses demonstrate that age reporting among the oldest-old Han Chinese and six minority groups combined in the 22 provinces included in the CLHLS was not as good as that in Sweden, Japan, England and Wales, but is similar to that in Australia and Canada, slightly better than in the U.S. (white, black and other races combined), and much better than that in Chile. In sum, age reporting among the oldest-old in China is as good as the average in developed countries, and one of the best in developing countries.

The interview refusal rate among the Chinese oldest-old was very low: about 2 percent among those who were not too sick to participate with proxy assistance. This high rate likely is due to the fact that the Chinese oldest-old in general like to talk to outside people, plus they stay at home without a job or other duties. Many of them and their family members may also feel honored to participate in survey interviews concerning healthy aging, as they may be proud of being a member of a long-lived group. Many of the disabled oldest-old agreed to participate in our healthy aging study through proxy assistance by a close family member. Those who were too sick to participate with proxy assistance were not interviewed. Instead the interviewers answered the question “Why was the interview not conducted or not completed?” The answers to this question can be used in data analysis to correct for selection bias. Refusal rates increase substantially among younger interviewees aged 65–79 (5.1%) and among adult children aged 35–65 (14.3%) because some of them did not want to devote their time to the interview. The overall refusal rate among all subjects aged 35 and older was 5.4%, The overall interview refusal rate was 3.0% and 4.5% in 2005 and 2008–2009, respectively. The decline in refusal rate in 2005 and 2008–2009 as compared to 2002 was mainly due to the fact that we had the largest adult children sub-sample in 2002 wave who had the highest refusal rate. The rates of loss-to-follow-up were 9.8%, 13.8%, 13.2% and 17.7% in 2000, 2002, 2005 and 2008–2009. The trend of increase in loss-to-follow-up rate, especially in the most recent 2008–2009 wave, is mainly due to the increasing migration that accompanied rapid economic growth.

We have conducted extensive evaluations of the data quality of all CLHLS waves, including assessments of mortality rate, proxy use, non-response rate, sample attrition, reliability and validity of major health measures, and the rates of logically inconsistent answers, with generally satisfactory results compared to other major aging studies. Factor analyses on cognitive functioning, physical performance, and functional limitations demonstrate that the interviewees’ answers to questions concerning different aspects of the same category are generally consistent. The rates of logically inconsistent answers and incomplete data are low (1–3%). We did not find substantial underreporting of death rates in our surveys. The morbidity data in CLHLS are slightly better than that in the National Health Service Survey (Gu, 2008). Careful assessments have led us to believe that the data quality of the CLHLS including the most recent waves conducted in 2005 (Gu, 2008) and 2008–2009 (Chen, 2010; Shen, 2010) is generally good. Goodkind (2009) wrote in his review on CLHLS published in Population Studies Vol. 63, No. 3, 2009: “The story emerging from these chapters is that the quality of reporting, despite a few flaws endemic to this kind of survey, was fairly good.”

We also realize that some problems exist in the CLHLS datasets. For example, we find that information on self-reported number of natural teeth and cause of death of deceased interviewees reported by next-of-kin are not reliable. Similar to other studies focusing on the oldest-old, higher proxy use is a notable limitation. The higher proxy rate is related to older age, lower education, rural residence, lower cognitive functioning, and higher disability. Therefore, it would be better to add an indicator variable (i.e., either the presence or absence of a proxy) in the analyses when the aim of a proposed study is to examine the effects of these factors. Furthermore, we find that item incompleteness and sample attrition tend to be linked to age, gender, urban/rural residence, ethnicity, and health conditions. Although it is unlikely that these limitations will significantly affect the results, sufficient attention should be paid to them when verifying and reporting the outcomes of the related data analysis. We have produced several technical reports to address these data issues, which are available at our CLHLS Website, to help users to build robust analytical models taking into account the strengths and weaknesses of the CLHLS data.

2.6 Progress in publications and policy reports based on CLHLS data and CLHLS data availability

CLHLS datasets have been provided (free of charge) to scholars inside and outside of China for research, and about 600 researchers (not including their students and other research team members) formally registered as CLHLS data users. Researchers interested in using the CLHLS data need to first sign a Data Use Agreement which can be downloaded from our Website, and then we will provide raw data to them free of charge.

Interested users inside China please contact:

Ms. Li Faju, Center for Health Aging and Development Studies, National School of Development, Peking University, Beijing, 100871, China; Tel: 0086-10-62756914; Fax: 0086-10-62756843; E-mail: bridget.li@ccer.edu.cn; Website: http://web5.pku.edu.cn/ageing

Interested users from other countries than China please contact:

Dr. Huashuai Chen, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University; Durham, NC 27708; Phone: (919) 6607532; Fax: (919) 684-8569; E-mail: CLHLS@duke.edu; Website: www.geri.duke.edu/china_study/index.html

So far, worldwide users of CLHLS datasets have published:

9 books;

75 papers in international peer-reviewed journals in English in U.S and Europe;

162 papers in peer-reviewed journals in Chinese in China;

18 Ph.D dissertations and 24 MA degree theses were defended/passed.

Science published a special report in 1999 about our CLHLS project. The review article in Science in 2001 indicated that CLHLS is the worldwide largest study on healthy longevity.

Our four major policy reports based on censuses, CLHLS and other data submitted to the Chinese central government were noted in written by the Prime Minister and 3 Vice Prime Ministers, respectively, in 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2012. Mainly based on our 2003 policy report, China National Aging Committee issued No. 48 (2003) official paper; since then, oldest-old received much more attention nationwide. Another policy report based on CLHLS was recommended to the central government by the general office of China Academy of Sciences. Other more than 20 policy reports based on CLHLS was submitted to various governmental agencies.

3. Empirical Analysis Related to Healthy Aging Policy based on the Unique CLHLS Datasets

3.1 Optimism and happiness is one of the secrets of healthy longevity

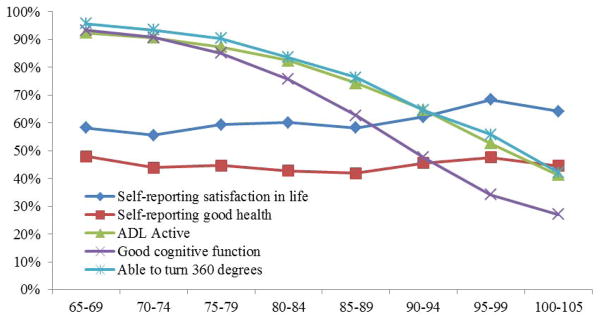

As shown in Figure 1 based on our CLHLS 2011–2012 newest data, for example, our multi-wave CLHLS data repeatedly show that the proportion of elders that are active in daily living, have good capacity of physical performance, and normal cognitive functioning drops dramatically from ages 65–69 to 100–105. The percent self-reporting satisfaction in current life and self-reporting good health, however, remain almost constant from age 65–69 to 100–105 (see Figure 1). This may suggest that being more positive in one’s outlook on life, i.e. optimism and happiness, is one of the secrets of longevity (Zeng and Vaupel, 2002).

Figure 1.

Percent of health indicators and subjective well-being, CLHLS 2011–2012

3.2. Gender differentials of the oldest-old

Based on the CLHLS data from a sample of nearly 9,000 people aged 80–105 interviewed in 22 provinces in 1998, Zeng, Liu and George (2003) found that gender differentials in educational attainment among the Chinese oldest-old are enormous: many more women are illiterate. Compared with the oldest-old men, the oldest-old women are more likely to be widowed and economically dependent, much less likely to have pensions, and thus they are more likely to live with their children and rely on children for financial support and care. The female oldest-old in China are also seriously disadvantaged in activities of daily living, physical performance, cognitive function, and self-reported health, as compared with their male counterparts; these gender differences are more marked with advancing age. The large gender differentials among the Chinese oldest-old need serious attention from society and government, and any old age insurance and service programs/policies to be developed or reformed must benefit older women and men equally (Zeng, Liu and George, 2003).

3.3 The association of childhood socioeconomic conditions with health aging at oldest-old ages

Based on unique data from the largest-ever sample of the Chinese oldest-old aged 80 and older collected in CLHLS, our multivariate logistic regression analyses (Zeng et al., 2007) show that either receiving adequate medical service during sickness in childhood or never/rarely suffering from serious sickness during childhood significantly reduces the risk of being ADL (activities of daily living) impaired, being cognitively impaired, and self-reporting poor health by 18–33% at the oldest-old ages. Estimates of effects for five other indicators of childhood conditions are similarly positive, but mostly not statistically significant. Multivariate survival analysis shows that better childhood socioeconomic conditions in general tend to reduce the four-year period mortality risk among the oldest-old. But after additionally controls for 14 covariates are put into the model, the effects are not statistically significant, thus suggesting that most of the effects of childhood conditions on oldest-old mortality are indirect – at least to the point of affecting current health status at the oldest-old ages, which itself is strongly associated with mortality.

Based on a new dataset with 12,281 oldest-old participants aged 80+ plus 4,285 young-old aged 65–79 from 2008–2009 wave of CLHLS and structural equation analysis, we decomposes the direct and indirect (via adulthood socioeconomic status) effects of childhood conditions on current health at old ages. We found that, among oldest-old, the direct effect is statistically significant and it is considerably larger than the indirect effects; the total direct and indirect effects of childhood conditions are substantially larger than that of adulthood socioeconomic status. In contrast, among young-old, direct effect of childhood conditions on current health is not statistically significant, while the total direct and indirect effects are substantially smaller and the indirect effects are much stronger than that among oldest-old. These results indicate that the effects of childhood conditions on health in late life persist to and become even more profound at oldest-old ages (Shen and Zeng, 2012).

While acknowledging limitations of our analyses due to a lack of information on childhood illness, the oldest-olds’ recalling errors, and other data problems, we conclude, based on studies, that policies that enhance childhood health care and children’s socioeconomic wellbeing can have large and long-lasting benefits up to the oldest-old ages.

3.4 Co-residence between old parents and adult children may be a win-win choice

Shen (2011) investigated the casual effect of living arrangement on the health status and life quality among the elderly. Instrumental analyses show that although the aged who live with their children show no evident advantages in physical health, they are significantly more advantageous in cognitive function, self-rated health and self-rated life satisfaction. Noticeably, if the sample is divided by the marital status of the elderly, the protective effect of intergenerational co-residence on health and life quality is much stronger for the widowed/divorced elderly. Subsequently, stepwise regressions show that part of the effect of co-residence is mediated by the income level and availability of medical services. However, even if these two factors are controlled for, co-residence between old parents and their child(ren)/grandchildren still has significant and positive direct effects on cognitive function and life quality of the elderly.

Shen (2011) also investigated how the living arrangement affects the labor participation and self-rated health among the adult offspring of the elderly, which is largely unknown in China. It’s found that co-residence with the elderly parents significantly increases the labor force participation of the female adult children by 23%. Besides, co-residence with parents increases the working hours of the children by 19.9%, and this effect is more evident for female as well as for rural children. Subsequent empirical analyses reveal the mechanism: in the intergenerational families, the elderly parents help to relieve the housework burden of the children, especially the daughters, thus the children could devote more time in working. It’s also found that co-residence with the elderly parents is beneficial for the self-rated health of the children, especially for the daughters. The analyses based on the subsamples show that the positive effect of co-residence living arrangement on self-rated health is more significant for the adult children with healthier and younger-old parents, as well as for the adult children with lower socio-economic status.

The policy implications of these empirical findings are: it is beneficial for both old parents and adult children to promote intergenerational co-residence, and encouraging such a win-win living arrangement may be considered as one of the familial responses to the rapid aging.

3.5 Longitudinal study denies traditional son preference in China

Based on analyzing the multi-wave datasets of CLHLS conducted in 2002, 2005 and 2008–2009, Zeng et al. (2012) clearly demonstrate that, controlling for various confounding factors, having daughter(s) is beneficial at older ages in China, with regards to enjoying greater filial piety from and better relationships with children, satisfaction with care provided by children, and also maintaining higher cognitive capacity and reducing mortality risk. Such daughter-advantages are more profound among oldest-old aged 80+ as compared to young-old aged 65–79, and surprisingly more profound in rural areas as compared to urban areas, while son-preference is much more prevalent among rural residents. This study indicates that educational propaganda aimed at informing the public that having daughter(s) is beneficial for old age care will be helpful in efforts of reducing prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortions in China, especially in rural areas.

3.6 The new rural cooperative medical scheme: financial protection or health improvement?

Cheng (2012) investigated the impacts of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), a governmental heavily-subsidized voluntary health insurance program adopted in 2003 in rural China. Using the longitudinal datasets of CLHLS, this study employs multiple identification strategies including Fixed-effect model, Propensity Score Matching with Difference-in-difference, Two-part Model and Heckman selection Model, etc. to correct potential biases. We find that NRCMS increases the NRCMS participants’ access to the medical service and stimulates their service utilization, and hence improves their health status significantly. Meanwhile, we do not find that the NRCMS participants’ medical expense burden was alleviated significantly, but we found the proportion of the out-of-pocket medical expense to the total expense decreased indeed which means the prices of medical services reduced for NRCMS participants. So, we conclude that NRCMS’ main function is helping to maintain and improve the health status of rural residents, while it only provides very limited financial protection for its participants from catastrophic diseases (Cheng, 2012).

3.7 The effect of marriage on health and care costs among the Chinese elderly

With the increase in life expectancy, the period of being widowed will increase, and the health status of old adults especially women will deteriorate after the death of their spouses, and they have to rely more on their adult children who are in labor market and other people in the society to deliver daily-care services, if they are disabled. As a result, the economic cost and the opportunity cost will increase remarkably. However, there are few published studies about the effects of marriage on health and care costs among the Chinese elderly. Through the systematic study of the interactive influences between marriage and health outcome of the elderly and the effects of marriage on caring costs, Chen (2011) presents new research findings in this field.

Controling for the endogeneity problem, Chen (2011) discovered that marriage has no significant effects on ADL (activity of daily living) and self-reported health of the elderly. But marriage has significant and positive effects on IADL (instrumental activity of daily living), cognition, and depression symptoms of elderly. After the death of spouse, the IADL function and cognition ability of elderly deteriorates while the depression symptoms increase. On the other hand, remarriage significantly improves the health status of elderly in the follow-up periods. We also find that the effect of marriage formation and dissolution on IADL, cognition ability, and depression tendency is time-varying and will diminish 3–5 years after the remarriage or bereavement event occurred.

We use Weibull model, Logistic model, and time-varying Cox proportional model to analyze the effects of marriage on mortality rates of elderly. The results show that widowhood will significantly increase the mortality risk of elderly by 16 percent, adjusting for various confounding variables. Meanwhile, the remarriage events significantly decrease the mortality risk of elderly.

Through multi-variable regression methods, we estimate the marital status-age-sex-rural/urban-residence-specific care cost per year among ADL impaired elderly, and the care costs in the last month before death of the elderly. We find that the daily-care costs of the widowed is significant higher than the married while the last-month care costs of the dying widowed is lower than the dying married. It may due to the fact that the mechanisms of the daily-care costs are different from that of the before-dying care costs. The daily-care of ADL impaired elderly is less professional than that of the dying elderly so that the spouse may act as caregiver and the costs may be relatively lower, while the care for the dying elderly people is quite professional and the spouse is less likely to substitute the role of formal caregivers. In addition, the surviving spouse of the dying elder may do him/herself or push their children to purchase the costly professional before-dying care services.

The policy implications of this study are obvious: our aging society needs to at least protect or even promote remarriage of elderly widows and widowers, in order to improve old adults’ health, wellbeing and to reduce the societal care costs.

3.8 Associations of environmental factors with elderly health and mortality

Zeng et al. (2010a) examined the effects of community socioeconomic conditions, air pollution, and the physical environment on elderly health and survival in China, based on CLHLS data from a nationally representative sample of 15,973 elderly residents of 866 counties and cities with multilevel logistic regression models in which individuals were nested within each county or city. After controlling for individual-level factors, communities’ gross domestic product per capita, adult labor force participation rate, and illiteracy rate were significantly associated with physical, mental, and overall health and mortality among the elderly in China. We also found that air pollution increased the odds of disability in activities of daily living (ADL), cognitive impairment, and health deficits; more rainfall was protective, reducing the odds of ADL disability and cognitive impairment; low seasonal temperatures increased the odds of ADL disability and mortality; high seasonal temperatures increased the odds of cognitive impairment and deficits; and living in hilly areas decreased the odds of ADL disability and health deficits. We concluded that the efforts to reduce pollution and improve socioeconomic conditions could significantly improve elderly health and survival. Our policy recommendation based on this study is that reducing environmental pollution also helps to realize healthy aging (Zeng et al., 2010a)5.

3.9 The Association between religious participation and mortality among older Chinese adults

Zeng, Gu and George (2010) examined the association of religious participation with mortality using a longitudinal dataset collected from 9,017 oldest-old aged 85+ and 6,956 younger elders aged 65–84 in China in 2002 and 2005. Results show that, adjusted for demographic characteristics and family/social support and health practices, the risk of dying was 24 percent (p<0.001) and 12 percent (p<0.01) lower among frequent and infrequent religious participants than among non-participants for all elders. After baseline health was adjusted, the corresponding risk of dying declined to 21 percent (p<0.001) and 6 percent (not significant), respectively. Hazard model analyses comparing men and women and younger-old and oldest-old, respectively, show that gender differentials in the effects of religious participation on mortality among all elderly aged 65+ were not significant. However, this association among younger-old men was significantly stronger than among oldest-old men, while age differentials among women were not significant. The finding of this study implies that the normal religious participation is a positive social phenomenon that is useful for elderly wellbeing and survival and may need to be encouraged in responding to the serious challenges of rapid population aging (Zeng, Gu and George, 2010).

3.10 Interactions between the social/behavioral and genetic factors may affect health and mortality at advanced ages

Based on data from 760 centenarians and 1,060 middle-age controls (all Han Chinese), Zeng et al (2010b) contributed bio-demographic insights/syntheses concerning magnitude of effects of the FOXO genotypes on longevity. We estimate independent and joint effects of the genotypes of FOXO1A and FOXO3A genes on long-term survival, considering carrying or not-carrying the minor allele of the SNP of another relevant gene. We found substantial gender differences in the independent effects; positive effects of FOXO3A and negative effects of FOXO1A largely compensate each other if one carries both, although FOXO3A has a stronger impact. Ten-year-follow-up cohort analysis shows that at very advanced ages 92–110, adjusted for various confounders, positive effects of FOXO3A on survival remain statistically significant, but no significant effects of FOXO1A alone; GxG interactions between FOXO1A-209 and FOXO3A-310 or FOXO3A-292 increase mortality risk by 32–36%(P<0.05); GxE interaction between FOXO1A-209 and regular exercise reduces mortality risk by 31–32%(P<0.05).

Analysis of CLHLS longitudinal survey and genotype/phenotype data from 877 individuals aged 90+, Zeng et al. (2012) found that adjusted for various potentially confounding factors, carrying ADRB2 SNPs rs1042718 or rs1042719 minor alleles significantly reduced risk of negative emotion. Interactions between negative emotion and carrying rs1042718 or rs1042719 minor allele significantly lowered cognitive function. Interactions between regular exercise and carrying rs1042718 minor allele significantly increased cognitive function; interactions between regular exercise and carrying rs1042718 or rs1042719 minor allele significantly increased likelihood of self-reporting good health; interactions between social-leisure activities and carrying rs1042719 minor allele significantly increased likelihood of self-reporting good health.

We also found that positive effects of regular exercise and social-leisure activities on cognition and self-reported health, and adverse effect of negative emotion on cognition were much stronger among carriers of rs1042718 or rs1042719 alleles, compared to non-carriers. This implies that policies and health promotion programs considering individuals’ genetic profiles (with appropriate protection of privacy/confidentiality) would yield increased benefits and reduced costs to the programs and their participants.

4. Future perspectives

To continue and extend the productive momentum of demographic, economic, sociological and gerontological analysis using the CLHLS datasets, we plan to conduct the following tasks aiming at extending our CLHLS into a truly interdisciplinary study: (1) To continue collection of longitudinal follow-up data on changes in health status and mortality at old ages, through conducting the CLHLS 7th waves in 2014–2015 which is funded by NSFC and NIH. The follow-up data to be collected will be used to address scientific questions on the effects of social, economic, behavioral and genetic factors and their interactions on morbidity and mortality among elderly adults. (2) To conduct interdisciplinary and integrated multilevel data analysis. We propose using multiple specific and summary indices to measure different dimensions of healthy aging that are available in our CLHLS multi-wave longitudinal data collected since 1998. We aim to shift the paradigm of healthy aging studies from single-level to multi-level investigation by interdisciplinary analysis on social, economic, and behavioral data at both the individual and community levels, and genotypic data at the molecular level. We will particularly emphasize investigating the effects of interactions among social, economic, behavioral and genetic factors on healthy aging. (3) To continue distribution of CLHLS datasets to interested researchers free of charge.

There is no doubt that there are a lot of difficulties and challenges ahead of us. We, however, are dedicated to continue to do our best for science and society and for those senior interviewees and their family members as well as our colleagues, friends and funding agencies who have supported CLHLS study since 1998 when the baseline survey was conducted.

Acknowledgments

The CLHLS surveys in 1998–2015 have been Jointly supported by China National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC), the U.S. National Institute on Aging (NIA), China National Foundation for Social Sciences, United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA), Hong Kong Research Grant Council, Chinese Ministry of Education and Peking University 211 Program. The sub-sample of each of the elderly interviewee’s one adult child in the eight provinces conducted in conjunction with the 2002 and 2005 CLHLS waves was supported by Taiwan Academy Sinica and Mainland China Social Sciences Academy. China Center for Economic Research, National School of Development of Peking University and Center for Study of Aging and Human Development, Medical School of Duke University have provided institutional supports. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research has provided support for international training. The filed works of the nationwide survey of the CLHLS before 2009 were conducted by the Mainland China Information Group Inc. (MIG), and the nationwide survey as well as the survey field work and the health exams in the longevity areas since 2009 were conducted by the China Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. We are very grateful to all scholars, survey supervisors, staff members, local medical personals and interviewers (too many to be named here) who contributed to the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, and we sincerely thank all interviewees and their families for their voluntary participation in this study.

Footnotes

The study reported in this article is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71110107025), NIA/NIH (2R01 AG023627) and Ministry of Education of China (2009JJD790001).

The survey interviews of the 5th and 6th wave of the CLHLS in all of the randomly selected half of the counties and cities in the 22 provinces except the 7 and 8 longevity areas were conducted in 2008 and 2011, respectively. In addition, as part of the 5th and 6th wave of the CLHLS, we also conducted the more in-depth study including the CLHLS survey interviews plus home-based health exams and blood/urine samples collection by medical personnel of China CDC network in the 7 and 8 longevity areas in 2009 and 2012, respectively. Thus, the 5th and 6th wave of CLHLS was conducted in 2008–2009 and 2011–2012. Consequently and similarly, we will conduct the 7th wave of CLHLS in 2014–2015.

We presented the age-gender distributions of the total samples of CLHLS in Table 1. The detailed age-gender distributions of the sub-samples of the adult-children, the interviews and health exams in the longevity area as well as the centenarians’ children therein are out of the scope of this chapter focusing on a general introduction of CLHLS, and they are described in the corresponding technical reports.

The paper of Zeng et al., (2010) on “Associations of Environmental Factors with Elderly Health and Mortality in China” has won the 2011 AJPH (American Journal of Public Health) Paper of the Year Award, in recognized its excellence at the annual American Public Health Association Awards Ceremony on October 30, 2012 in San Francisco.

References

- Chen Huashuai. Assessment of the quality of the cross-sectional data collected in the 2008–2009 wave of Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. In: Zeng Yi., editor. Research on Elderly Population, Family, Health and Care Needs/Costs. Beijing: Science Press; 2010. pp. 350–352. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen Huashuai. PhD dissertation. Peking University; 2011. The effect of Marriage on Health and Care Costs among the Chinese Elderly. Supervisor: Professor Yi Zeng. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Lingguo, Zhang Ye. The New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme: Financial Protection or Health Improvement? Economic Research. 2012;2012(1):120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ, Kisker EE. Mortality crossovers: Reality or bad data? Population Studies. 1986;40:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ, Li S. The effect of age misreporting in China on the calculation of mortality rates at very high ages. Demography. 1991;28(2):293–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo IT, Preston SH. Effects of early-life conditions on adult mortality: A review. Population Index. 1992;58(2):186–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman JW. Sample size requirements for matched case-control studies of gene–environment interaction. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:35–50. doi: 10.1002/sim.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind Daniel. In: Review on the book “Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions”. 2009 YI ZENG, POSTON DUDLEYL JR, VLOSKY DENESEASHBAUGH, GU DANAN, editors. Vol. 63. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. p. xv_435. t134.95. This book review was published in Population Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg EM. The failures of success. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1977;55:3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Danan. General data quality assessment of the CLHLS. In: Zeng Yi, Poston Dudley, Vlosky Denese Ashbaugh, Gu Danan., editors. Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions. Vol. 2008. Dordrecht: Springer Publisher; 2008. pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez LM, Blazer DG, editors. IOM (Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences) Committee. Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the nature/nurture debate. Washington, D.C: National Academia of Sciences; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF. Aging, natural death and the compression of morbidity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303:130–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG. Changing concepts of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1982;60:183–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Naohiro. Aging in China: Demographic Alternatives. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1988;3:21–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston DL, Jr, Luo H. Zhongguo 2000 nian shaoshu minzu de nian ling dui ji he shu zi pian hao (Age structure and composition of the Chinese minorities in 2000) Zhongguo Shaoshu Minzu Renkou (Chinese Minority Populations) 2004;19(3):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Ke. Assessment of the quality of the follow-up mortality data collected in the 2008–2009 wave of Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. In: Zeng Yi., editor. Research on Elderly Population, Family, Health and Care Needs/Costs (in Chinese) Beijing: Science Press; 2010. pp. 352–354. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Ke. PhD dissertation. Peking University; 2011. Comprehensive Analyses of the Living Arrangement among Chinese Elderly—Its Influential Factors and the Effects on Well-being. Supervisor: Professor Yi Zeng. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Ke, Zeng Yi. The Direct and Total Effects of Childhood Conditions on Current Health in Oldest-old are Stronger than that in Young-old. Paper presented at international conference on “Advances in Methodology and Applications: Biodemography and Multistate Event History Analysis on Healthy Aging”; Beijing and HangZhou. Oct. 15–18, 2012.2012. [Google Scholar]

- Suzman RM, Willis DP, Manton KG. The oldest old. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey BB. Sharing increasing costs on declining income: the visible dilemma of the invisible aged. In: Suzman RM, Willis DP, Manton KG, editors. The oldest old. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 381–393. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Population Division. World population prospects: the 2010 revision. New York: [Access date: Nov. 16, 2011]. 20011. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/unpp/panel_population.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel JW. Analysis of population changes and differences. Presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; April 1992.1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel JW, Carey JR, Christensen K, Johnson TE, Yashin AI, Holm NV, Iachine IA, Kannisto V, Khazaeli AA, Liedo P, Longo VD, Zeng Y, Manton KG, Curtsinger JW. Biodemographic trajectories of longevity. Science. 1998;280(5365):855–860. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zeng Y, Jeune B, Vaupel JW. Age validation of Han Chinese centenarians. GENUS - An International Journal of Demography. 1998;54:123–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Vaupel JW, Xiao Z, Zhang C, Liu Y. The healthy longevity survey and the active life expectancy of the oldest old in China. Population: An English Selection. 2001;13(1):95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Vaupel James W. Functional Capacity and Self-Evaluation of Health and Life of the Oldest Old in China. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58:733–748. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi*, Yuzhi Liu, George Linda. Gender Differentials of Oldest Old in China. Research on Aging. 2003;25:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Poston Dudley, Vlosky Denese Ashbaugh, Gu Danan., editors. Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions. Dordrecht: Springer Publisher; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Gu Danan, Land Kenneth C. The Association of Childhood Socioeconomic Conditions with Healthy Longevity at the Oldest-Old Ages in China. Demography. 2007;44(3):497–518. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Gu Danan. Reliability of Age Reporting among the Chinese Oldest-old in the CLHLS Datasets. In: Zeng Yi, Poston Dudley, Vlosky Denese Ashbaugh, Gu Danan., editors. Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions. Chapter 4. Dordrecht: Springer Publisher; 2008. pp. 61–80. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yi Zeng, George Linda K. Population Aging and Old-Age Care in China. In: Dannefer Dale, Phillipson Chris., editors. Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology. Thousand Oaks/CA/USA: Sage Publications; 2010. pp. 420–429. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Gu Danan, George Linda. Association of religious participation with mortality among older Chinese adults. Research on Aging. 2010;33(1):51–83. doi: 10.1177/0164027510383584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Gu Danan, Purser Jama, Hoenig Helen, Christakis Nicholas. Associations of Environmental Factors with Elderly Health and Mortality in China. American Journal of Public Health. 2010a;100(2):298–305. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Cheng L, Chen H, Cao H, Hauser E, Liu Y, Xiao Z, Tan Q, Tian X, Vaupel JW. Effects of FOXO Genotypes on Longevity: A Bio-demographic Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2010b;65A(12):1285–1299. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq156. (Yi Zeng and Xiao-Li Tian are co-corresponding authors) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Cheng Lingguo, Zhao Ling, Li Jianxin, Feng Qiushi, Chen Huashuai, Shen Ke, Zhang Fengyu, Tan Qihua, Gregory Simon G, Yang Ze, Gu Jun, Tian Xiao-Li, Hauser Elizabeth R. Interactions between Social/behavioral Factors and ADRB2 Gene May Affect Health at Advanced Ages. Paper presented at the bio-demography conference; May 3–4, 2011; Durham. 2012. submitted to international peer-review journal for consideration of publication. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Sereny Melanie, Gu Danan, Vaupel James W. Longitudinal Study Denies Traditional Son Preference in China -- Many Chinese Prefer Sons but Daughters Provide Better Care for Old Parents. 2012. Manuscript submitted to peer-reviewed international journal for consideration of publication. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Yi, Chen Huashuaib, Wang Zhenglian. Analysis on Trends of Future Home-based Care Needs and Costs for Elderly in China. Economic Research. 2012;47(10):134–149. [Google Scholar]