Abstract

Purpose

Aerobic exercise training has been used in patients with stable heart failure (HF) to reduce the risk of clinical events. However, due to patient heterogeneity, some patients may experience a decrease in functional capacity due to such training. The purpose of this study was to estimate the proportion of HF patients participating in a training program who had negative responses to such therapy and to compare them to a concurrent control group.

Methods

Baseline and 3 mo peak VO2 measurements were obtained on 1870 HF subjects who were randomized to receive either an exercise training program or a control program of usual care without exercise training. The exercise program consisted of supervised walking or stationary cycling 3 days per week for 12 weeks as well as a 2-day per week home exercise program after completing 18 supervised sessions. A negative response was defined as a baseline-to-3 mo decrease in peak VO2 of at least 5 mL·kg−1·min−1, which was two times the standard deviation (SD) of the control group’s change in peak VO2.

Results

The mean (SD) change in peak VO2 in the exercise group and control group was 0.8 (2.5) mL·kg−1·min−1 and 0.2 (2.5) mL·kg−1·min−1, respectively (p < 0.001). The percentage of negative responders in the exercise and control groups was 0.9% and 2.3% (p = 0.02).

Conclusions

The low negative response rate in the exercise group combined with the slightly higher rate in the control group and equal variability in the exercise and control groups suggests that few if any subjects had training-related negative peak VO2 responses. These findings support current exercise recommendations for HF patients.

Keywords: aerobic capacity, training program, response variability, negative threshold

INTRODUCTION

Paragraph Number 1

Aerobic exercise training in patients with stable heart failure (HF) has been shown to be beneficial with respect to increasing functional capacity and potentially reducing clinical events (10, 5). However, due to individual heterogeneity, it is possible that functional capacity, as measured by peak oxygen uptake (VO2) during cardiopulmonary exercise (CPX) testing, significantly decreases in some individuals in response to exercise training. Such negative responders to exercise training, if they exist, would be important to identify so that they would not be prescribed this intervention.

Paragraph Number 2

In non-HF, sedentary subjects undergoing 4 to 6 mo of aerobic exercise training, Bouchard et al. (4) recently reported negative response rates of 8% to 13% in some metabolic variables, including resting systolic blood pressure, fasting HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and insulin. Prior investigations of the heterogeneous responses to exercise training have used gene mapping and linkage analysis (11), as well as familial aggregation methods (12). More recently, a 21-week combined endurance and strength training study in older adults resulted in individual peak VO2 responses ranging from an 8% decrease to a 42% increase (8).

Paragraph Number 3

The primary challenge in identifying a negative responder to exercise training is that a decrease in peak VO2 can occur for reasons unrelated to the training intervention. These reasons can include true physiological changes due to cardiac disease progression or other changes in health such as anemia, pulmonary dysfunction, or neuromuscular disorders. A decrease in peak VO2 can also occur due to random variability, which includes day-to-day biological variability and the technical variability involved in CPX testing. Thus, it is very important to set a reasonable threshold for declaring an individual to be a negative responder to training. For setting such a threshold, inclusion of a control group of subjects who did not exercise train, but who received the same baseline and follow-up measures of peak VO2 measurements as the exercise training group, is mandatory.

Paragraph 4

The recent randomized clinical trial of 2331 HF subjects, Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training (HF-ACTION), provides a unique opportunity to estimate the proportion of negative responders to exercise training among patients with HF with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (10). HF-ACTION randomized 2331 subjects in a 1:1 fashion to exercise and control groups. The vast majority of subjects in both groups underwent protocol-specified baseline and 3 mo follow-up peak VO2 tests. The main objective of this paper was to search for evidence of a negative peak VO2 response among subjects assigned to the HF-ACTION exercise training group, using the distribution of change in peak VO2 in the control subjects to set a reasonable threshold for a negative response. Our secondary objective was to estimate the random variability inherent in peak VO2 testing using a subset of 405 subjects who underwent two peak VO2 tests at baseline, within approximately one week of each other (1). This allowed us to determine the within-subject random variability, which helped gauge the relative magnitude of random variability versus the true change in peak VO2. Since exercise intolerance is a key manifestation of HF, better understanding peak VO2 response heterogeneity to exercise training is relevant to both patient care and whether or not exercise therapy should remain within guideline-based recommendation.

METHODS

Paragraph 5: Subjects

A complete description of the design and primary results of HF-ACTION has been previously reported (14, 10). Briefly, HF-ACTION was a multicenter trial that enrolled 2331 subjects with LVEF ≤ 35% and New York Heart Association functional class II-IV HF symptoms despite optimal medical and device therapy. Subjects were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either the exercise training group or the control group. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee for each center, and subjects provided written informed consent. The present study included the 1870 subjects (972 in the exercise group and 898 in the control group) who had both baseline and 3 mo CPX testing data.

Paragraph 6: Exercise training protocol

Exercise group subjects participated in a supervised exercise program of walking or stationary cycling with a goal of 3 sessions per week for a total of 36 sessions in 3 mo. Exercise was initiated at 15 to 30 minutes per session at a heart rate of 60% heart rate reserve (i.e., maximal heart rate on the baseline CPX test minus resting heart rate). After 6 sessions, the duration of the exercise was increased to 30-to-35 minutes, and intensity was increased to 70% of heart rate reserve. After completing 18 sessions, subjects were asked to add a 2-day per week home-based exercise program which continued throughout a mean follow-up of 2.5 yr.

Paragraph 7: Control group

Subjects in the control group were not provided with a formal exercise prescription. Both exercise and control group subjects received HF-related educational materials at the time of enrollment, including information on medications, fluid management, symptom exacerbation, sodium intake, and general physical activity recommendations of 30 minutes (as tolerated) of moderate-intensity exercise on most days of the week (7).

Paragraph 8: Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

CPX testing was performed at baseline and 3 mo after randomization. Subjects were tested using either a modified Naughton treadmill protocol (n= 1706) or a ramp (10 W·min−1, n=164) stationary cycle protocol; the same modality was used at both time points. During testing, subjects were encouraged to achieve a rating of perceived exertion >17 (very hard) on the Borg scale and respiratory exchange ratio >1.10. Peak VO2, as determined in the HF-ACTION CPX Core Laboratory, was defined as the highest VO2 per kg body mass for a given 15- or 20-second interval within the last 90 seconds of exercise or first 30 seconds of recovery (1).

Paragraph 9: Negative training response threshold

Since the goal of this study was to estimate the proportion of negative responders to exercise training, we needed to use data that was independent of the exercise group’s to set a negative peak VO2 response threshold. Since the control group did not undergo formal exercise training, we used its distribution of baseline-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 to set a negative peak VO2 response threshold. In particular, a subject was identified as a negative responder if the baseline-to-3 mo peak VO2 decreased 2 × SDcontrol mL·kg−1·min−1, where SDcontrol is the standard deviation of the baseline-to-3 mo changes in the control group. Those control group changes comprised a combination of true physiologic changes as well as those due to random biological and technical variability. However, the control group’s changes did not include those due to a formal training program. Thus, if there were significantly more negative responders in the exercise group, then that could suggest that exercise-training could be a culprit. Assuming a zero mean normal distribution for the control group’s changes, we would expect approximately 95% of the control group’s changes to be within ± 2× SDcontol mL·kg−1·min−1 of 0. The normality of the control group’s changes was assessed by a histogram.

Paragraph 10: Within-subject random variability

For a single peak VO2 measurement, we may write the observed peak VO2 value (Y) as the sum of the true peak VO2 value (T) and the within-subject random variability (E).

| Equation 1 |

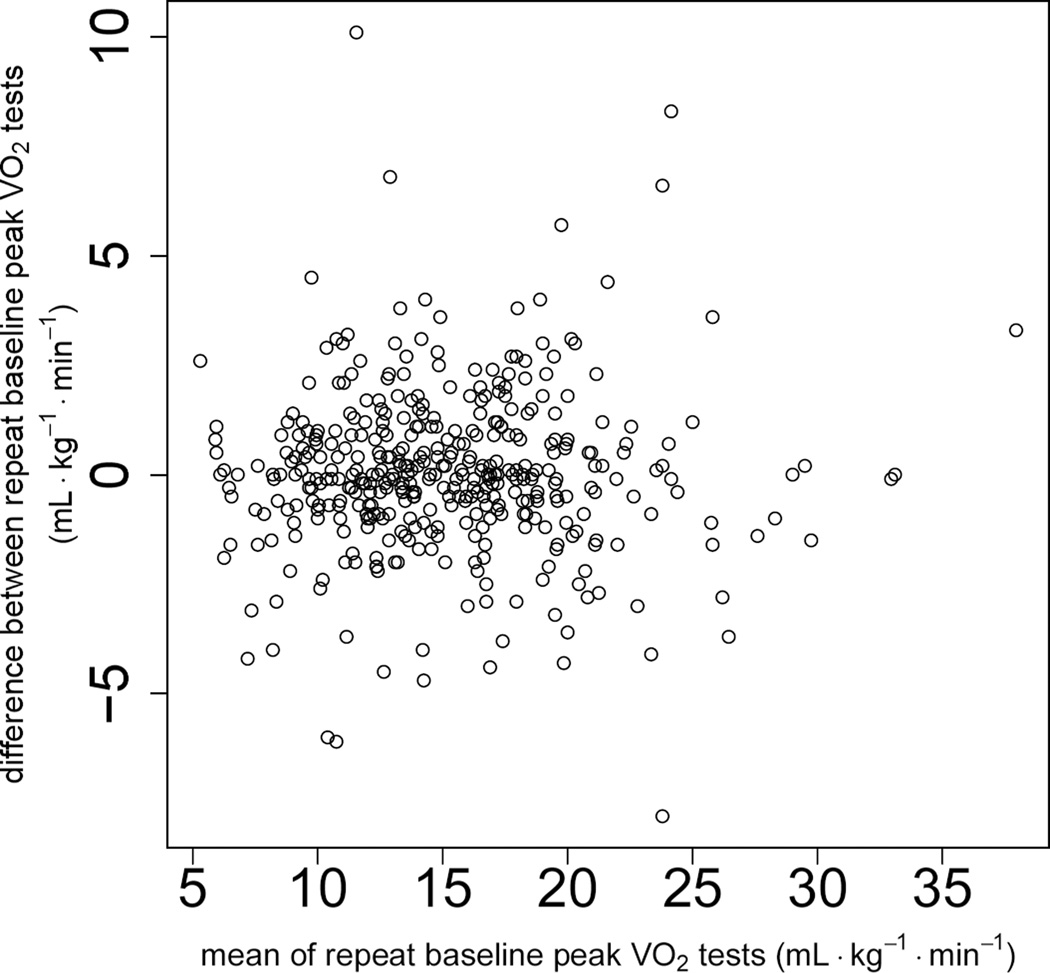

By “true” peak VO2, we mean the average peak VO2 measurement we would have obtained if the subject had undergone several peak VO2 tests within a short time period. If the magnitude of the variability does not depend on the true value— e.g., the variability is not larger for higher VO2 values—then we may quantify the magnitude of within-subject random variability in a single measurement by the standard deviation of E which we denote by SDEsingle. A Bland-Altman plot (2) verified that the within-subject random variability was independent of the subject’s true peak VO2 value.

Paragraph 11

For a single peak VO2 measurement, we only observe Y, but not T and E separately. The only way to estimate SDEsingle is by obtaining repeat baseline peak VO2 tests on some subset of subjects. To estimate SDEsingle, we used the 405 HF-ACTION subjects who had two repeat peak VO2 tests at baseline. For all 405 subjects, both tests were within approximately one week of each other. Those 405 subjects were a nonrandom sample of the HF-ACTION cohort since the protocol specified that for quality control purposes, the first 5 subjects at each clinical site as well as the first 100 subjects overall would undergo repeat baseline CPX tests. SDEsingle was obtained by computing variances for each of the 405 subjects, then taking the average of those variances (one variance for each subject), and finally taking the square root of the average of those variances. We verified that the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 405 subjects were similar to the 1870 subjects with peak VO2 measurements at baseline and 3 mo, so that SDEsingle could be accepted as a reasonable estimate of within-subject random variability for the 1870 subjects.

Paragraph 12

The within-subject standard deviation (SDEdelta) inherent in the baseline-to-3 mo random change in peak VO2 equals √2 × SDEsingle (3). To see why this is so, we note there is random variability inherent in both the baseline and follow-up peak VO2 measurements.

| Equation 2 |

Paragraph 13

Therefore, the change in peak VO2 is:

| Equation 3 |

Paragraph 14

SDEdelta is the standard deviation of Epost – Epre. We make the common assumption (6) that Epre and Epost are independent with the same standard deviation SDEsingle. Since the variances (i.e., squared standard deviations) of independent variables sum to the variance of their difference, we have:

| Equation 4 |

Paragraph 15

Analyses were performed using R, version 2.15.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Paragraph 16

Table 1 gives the baseline characteristics for the 1870 subjects who had peak VO2 data both at baseline and three-mo. Table 1 also gives the baseline characteristics for the 405 subjects with two peak VO2 tests at baseline that were within one week apart. As can be seen in Table 1, there were no practical baseline differences between the two cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the 405 HF-ACTION subjects with repeat baseline tests and 1870 subjects with baseline and 3 mo peak VO tests.

| Attribute | Subjects with repeat baseline tests (n = 405) |

Subjects with baseline and 3 mo tests (n = 1870) |

|---|---|---|

| Female Gender | 27% | 28% |

| NYHA Class (II / III) | 65% / 34% | 65% / 34% |

| Race (black / white) | 27% / 66% | 31% / 62% |

| Etiology of Heart Failure (Ischemic) | 53% | 52% |

| Baseline Peak VO2 (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 14.6 (9.3, 21.0) | 14.7 (9.5, 21.2) |

| Age (yr) | 59 (44, 74) | 59 (43, 75) |

| Body Mass Index (kg·m−2) | 30 (23, 39) | 30 (23, 40) |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (%) | 25 (16, 35) | 25 (16, 35) |

Unless specified otherwise, data are median (10th percentile, 90th percentile)

NYHA, New York Heart Association

Paragraph 17

Figure 1 is a Bland-Altman plot of the difference in repeat baseline peak VO2 tests for the 405 subjects vs. the average of those two tests. This plot shows that the mean difference in baseline tests was 0.05 mL·kg−1·min−1, which was not significantly different from 0 (t-test p-value=0.57). Moreover, variability was independent of the true peak VO2, e.g., the variability was not larger for higher VO2 values. Also, there was no significant difference between the treadmill and cycle subjects with respect to within-subject variability (Levene test p-value =0.32). Thus, SDEsingle is a reasonable estimate of the within-subject random variability in a single peak VO2 test. SDEsingle was calculated to be 1.33 mL·kg−1·min−1. Thus, the random variability SDEdelta inherent in the baseline-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 was √2 × SDEsingle = 1.9 mL·kg−1·min−1.

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plot of difference between the repeat baseline peak VO2 tests vs. the average of the repeat baseline peak VO2 tests for the 405 HF-ACTION subjects with repeat baseline tests.

Paragraph 18

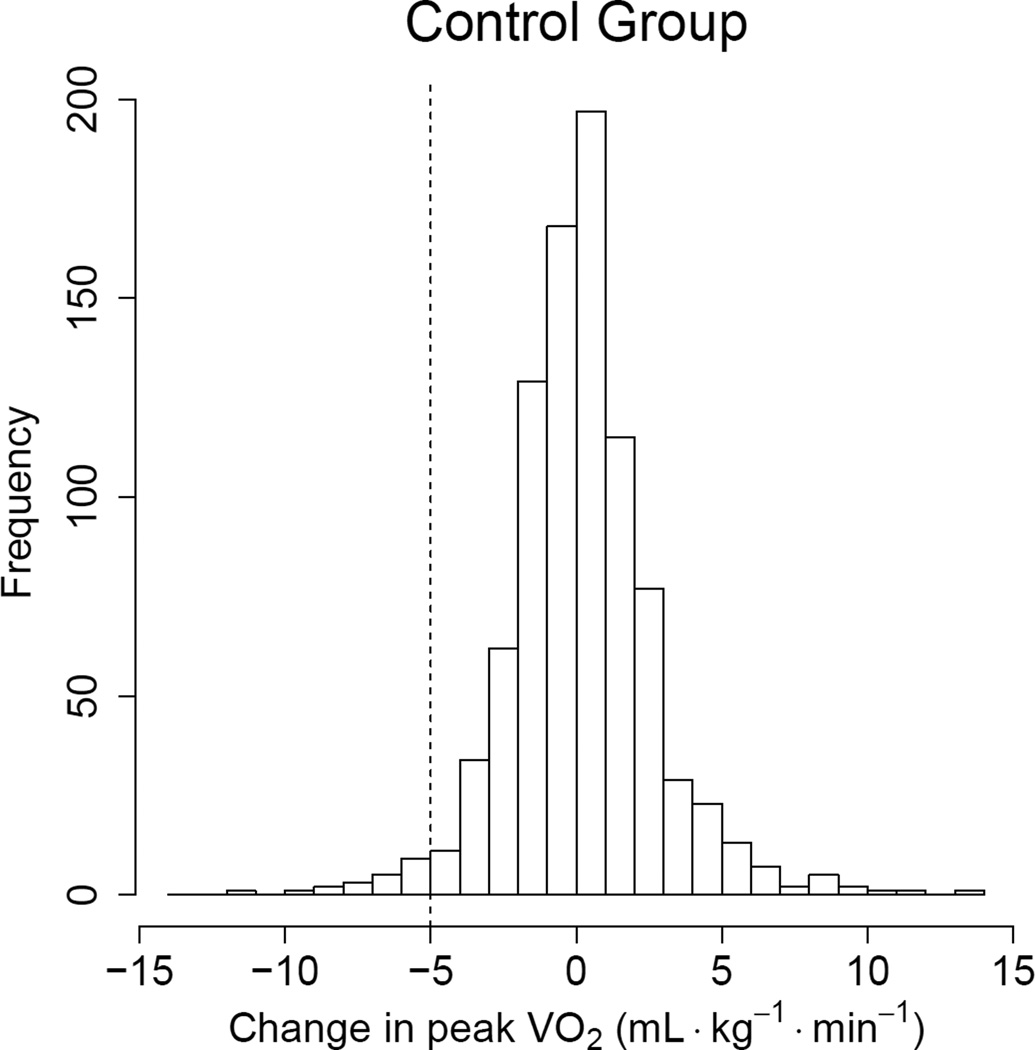

Figure 2a is a histogram of the baseline-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 for the 898 control group subjects. Their mean change in peak VO2 was 0.2 mL·kg−1·min−1 with standard deviation SDcontrol = 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1. Thus, our negative response threshold was a decrease of 2× SDcontrol = 5 mL·kg−1·min−1. We deemed this threshold as reasonable since the histogram was generally normally distributed and because 21 (2.3%) of the usual care subjects met this threshold, which is nearly equal to the 2.5% of usual care subjects we would have expected if the change in peak VO2 were perfectly normally distributed.

Figure 2.

a: Histogram of the 0-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 for the 898 control group subjects. The mean change in peak VO2 was 0.2 mL·kg−1·min−1 (SD = 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1) and 21 subjects (2.3%) were negative responders with a decrease in peak VO2 of at least 5 mL·kg−1·min−1. The negative response cutpoint is denoted by the dashed line.

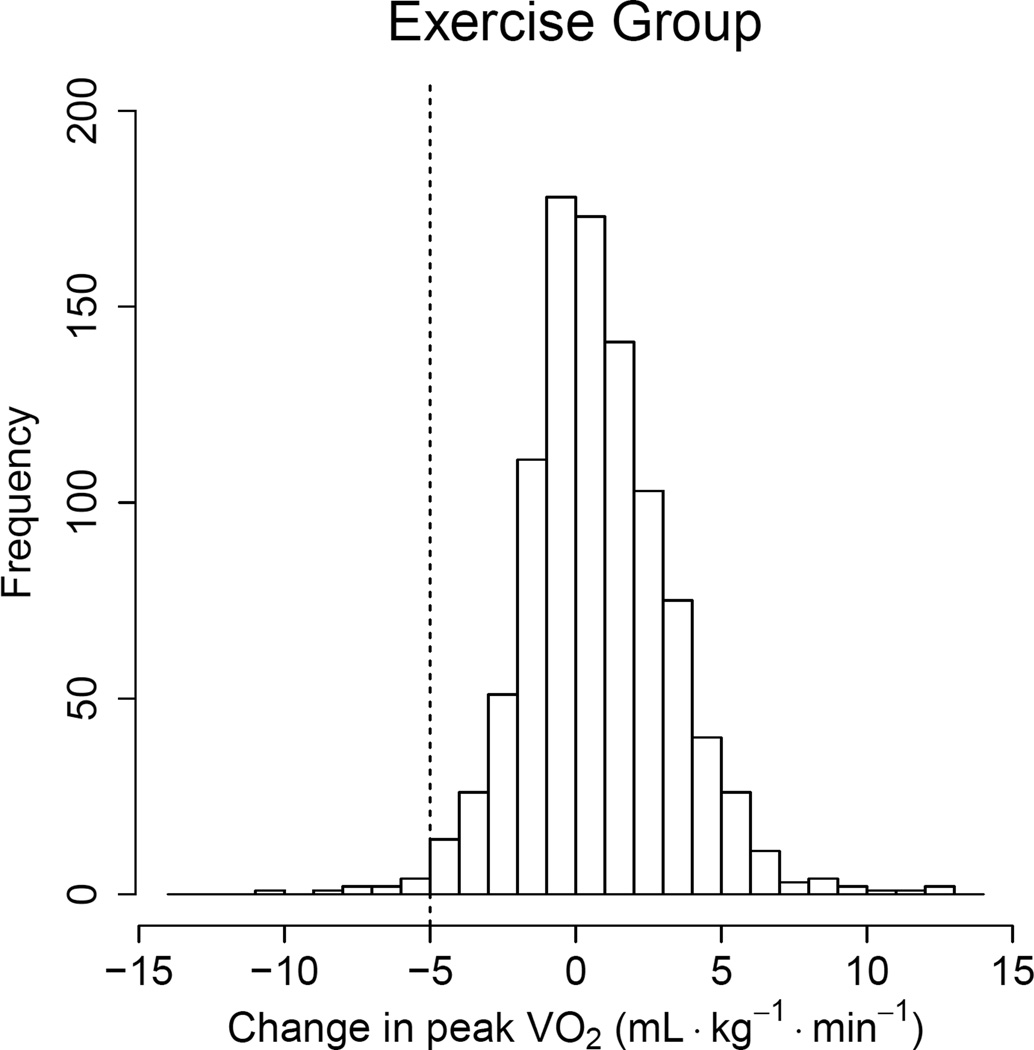

b: Histogram of the 0-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 for the 972 exercise group subjects. The mean change in peak VO2 was 0.8 mL·kg−1·min−1 and 9 subjects (0.9%) were negative responders with a decrease in peak VO2 of at least 5 mL·kg−1·min−1. The negative response cutpoint is denoted by the dashed line.

Paragraph 19

Figure 2b is a histogram of the baseline-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 for the 972 subjects in the exercise group. Their mean change in peak VO2 was 0.8 mL·kg−1·min−1 and 9 (0.9%) subjects met the negative response threshold of experiencing a decrease in peak VO2 ≥ 5 mL · kg−1·min−1. Importantly, the 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1 standard deviation of the change in peak VO2 in the exercise group (SDexercise) was the same as that in the usual care group. Indeed, the histograms in Figures 2a and 2b were nearly identical. This suggests that negative responses in the exercise group were virtually all unrelated to training. Otherwise, we would have expected to see a larger standard deviation in the exercise group and a longer negative tail in Figure 2b, neither of which occurred. Of note, SDEdelta ÷ SDexercise = SDEdelta ÷ SDcontrol = 1.9 mL·kg−1·min−1 ÷ 2.5 mL· kg−1 · min−1 = 0.76, so 76% of the variation in the change in peak VO2 among subjects in both exercise and usual care groups was due to within-subject random variability.

Paragraph 20

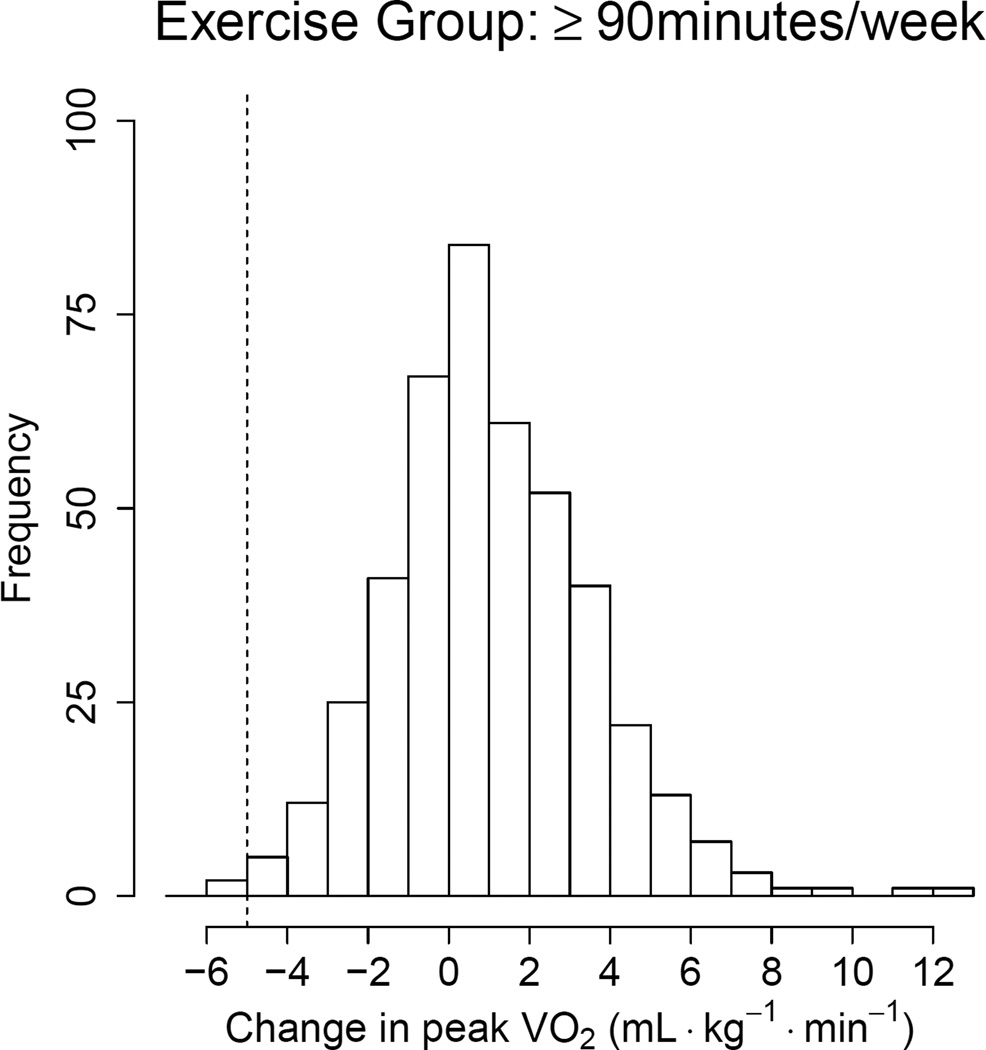

Finally, there was variable adherence to the training program in the exercise group, with subjects averaging 95 min·wk−1 of exercise (5th percentile = 0 min·wk−1, 1st quartile = 58 min·wk−1, 3rd quartile = 128 min·wk−1, 95th percentile = 185 min·wk−1). For the 438 exercise group subjects who exercised at least 90 min·wk−1, the mean change in peak VO2 was 1.1 mL·kg−1·min−1 (SD = 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1), with only 2 subjects (0.5%) meeting the negative response threshold. As seen in Figure 3, their histogram of the 0-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 is slightly skewed to the right, corresponding to peak VO2 increases. Indeed, only 2 of those 438 subjects (0.5%) met the negative response threshold.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the 0-to-3 mo change in peak VO2 for the 433 exercise group subjects who exercised ≥ 90 min·wk−1 during the first 3 mo of training. The mean change in peak VO2 was 1.1 mL·kg−1·min−1 (SD = 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1) and 2 subjects (0.5%) were negative responders with a decrease in peak VO2 of at least 5 mL·kg−1·min−1. The negative response cutpoint is denoted by the dashed line.

DISCUSSION

Paragraph 21

The current analyses suggest that any apparent negative effect of exercise training on peak VO2 or exercise tolerance occurs in a very small percentage of patients with HF and reduced LVEF. Indeed, using a negative response threshold that corresponded to a two standard deviation decline in the control group, slightly more control subjects (2.3%) met that threshold than did exercise subjects (0.9%) (Fisher’s p-value = 0.02). Moreover, the two groups had the same variability in observed changes in peak VO2 (standard deviation = 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1 in both groups) and very similar histograms. This suggests that negative responses were likely due to health changes unrelated to exercise training, random day-to-day biological variability, and the technical variability involved in the measurement of peak VO2. This is an important finding given that just two decades ago exercise training was not routinely embraced as a safe and effective therapy for patients with reduced LVEF, and supports current evidence-based guidelines that recommend exercise therapy to improve exercise tolerance in these patients.

Paragraph 22

A recent study by Bouchard et al. of 1687 non-HF sedentary subjects enrolled in six different exercise studies raised some potential concerns when they cited the relatively common occurrence of negative metabolic response to exercise training. They identified 12.2% of their subjects with a negative response for resting systolic blood pressure, 8.4% for insulin, 10.4% for triglycerides, and 13.3% for HDL-cholesterol (4). Unfortunately, our HF-ACTION database only includes follow-up exercise tolerance data and does not include follow-up data for those metabolic risk factors studied by Bouchard et al. Thus, we could not perform similar analyses to confirm their results in HF subjects. It is possible that exercise training negatively impacts metabolic risk factors in some individuals without negatively impacting exercise tolerance. However, it is important to note two differences in Bouchard et al.’s methodology from our own. First, Bouchard et al. defined a negative response as a 2 × SDEsingle decrease between baseline and follow-up at approximately 6 mo. As shown above, SDEsingle underestimates by a factor of √2 the within-subject random variability SDEdelta inherent in the difference between the baseline and follow-up measurements. Thus, even if all changes were due to random variability with no true changes unrelated to training, we would have expected about 8% of subjects to meet the 2 × SDEsingle negative response threshold for normal distribution reasons. Second, and more importantly, Bouchard et al. did not compare their negative response rates and the standard deviation of the risk factor changes to those of a control group who did not receive the exercise training. Without such a comparison, it is difficult to know the extent to which negative response was associated with training. Indeed, in our data we estimated the random variability SDEdelta for the change in peak VO2 to be 1.9 mL·kg−1·min−1, while the overall variability SDcontrol in the control group was 2.5 mL·kg−1·min−1. Thus, approximately one-fourth of the change in peak VO2 in the control group was true health-related change. Accounting for these true changes led us to use 2 × SDcontrol = 5 mL·kg−1·min−1 as the negative response threshold. Clearly, it will be very important to conduct further research on metabolic response to exercise with comparison to a control group of non-exercisers.

Paragraph 23

Our study had the following limitations. First, approximately 9% of the subjects (164 of 1870) were tested using a bike protocol while the remaining subjects were tested on a treadmill. Since bike values are likely to be about 10% lower than treadmill values, it is possible that the mean and SD of the peak VO2 change were different than if all subjects were treadmill tested. Second, adherence to the training exercise program was quite variable in the exercise group with 5th and 95th percentiles of 0 and 185 minutes per week of exercise, respectively. Third, it is possible that some of the control subjects engaged in exercise training. More generally, as has been noted in the literature (9, 13), to reliably identify a particular subject as a negative responder to an intervention (e.g., exercise training) would require a different study design than the parallel arm design that was used for our study. Indeed, a subject would need to undergo at least two distinct periods of exercise training as well as two distinct periods not training to estimate that subject’s individual variability associated with training and not training, respectively. Clearly such a “repeated crossovers” design would be more costly and difficult to execute than a parallel arm design. It is possible that in the future, patient characteristics will be discovered to be associated with negative response to training. However, until such time and given that the HF-ACTION study showed exercise to be safe while providing a modest reduction in risk for both all-cause mortality or hospitalization and cardiovascular mortality or HF hospitalization, recommendations to exercise may be made for the general HF patient rather than targeted towards specific HF patients.

Acknowledgments

The HF-ACTION trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors thank the HF-ACTION participants and investigators who gave their time and effort to completion of the study. The authors also thank Drs. Nancy Geller, Michael Lauer, and James Troendle for their critical review of the manuscript. The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Source of Funding: The data used for this analysis was collected through a study that was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: There were no conflicts of interest to be declared with companies or manufacturers who will benefit from the results of the present study.

References

- 1.Bensimhon DR, Leifer ES, Ellis SJ, et al. Reproducibility of peak oxygen uptake and other cardiopulmonary exercise testing parameters in patients with heart failure (from the Heart Failure and A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training) Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: measurement error. BMJ. 1996;312:1654. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard C, Blair CN, Church TS, et al. Adverse response to regular exercise: is it a rare or common occurrence? [[cited 2012 May 30]];PLoS ONE [Internet] . 2012 7(5):e37887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037887. Available from: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0037887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies EJ, Moxham T, Rees K, et al. Exercise based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub3. Issue 4; Art. No. CD003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daw EW, Province MA, Gagnon J, et al. Reproducibility of the HERITAGE family study intervention protocol: drift over time. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:452–462. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Chest Physicians; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112(12):e154–e235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karavirta L, Häkkinen K, Kauhanen A, et al. Individual responses to combined endurance and strength training in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:484–490. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f1bf0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obarzanek E, Proschan MA, Vollmer WM, et al. Individual blood pressure responses to changes in salt intake: results from the DASH-sodium trial. Hypertension. 2003;42:459–467. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091267.39066.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. for the HF-ACTION Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1439–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rankinen T, Pérusse L, Rauramaa R, et al. The human gene map for performance and healthrelated fitness phenotypes: the 2001 update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1219–1233. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice T, Després J-P, Pérusse L, et al. Familial aggregation of blood lipid response to exercise training in the Health, Risk Factors, Exercise Training, and Genetics (HERITAGE) family study. Circulation. 2002;105:1904–1908. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014969.85364.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senn S, et al. Individual therapy: new dawn or false dawn. Drug Information Journal. 2001;35:1479–1494. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM, Lee KL, et al. for the HF-ACTION Trial Investigators. Heart failure and a controlled trial investigating outcomes of exercise training (HF-ACTION): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2007;153(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]